This summer and fall the Olympic Museum in Lausanne, Switzerland is hosting several exhibitions and events related to sports photography.

One of the exhibitions, Who Shot Sports: A Photographic History, 1843 to The Present, opened at the Brooklyn Museum last summer and has since been traveling around the U.S. and Europe, making a six-month stop at the Olympic Museum before it returns to the U.S. next May.

A second show, Rio 2016 Seen Through the Lens of Four Photographers, is comprised of a series of images that were made at the 2016 Summer Olympics by four participating photographers.

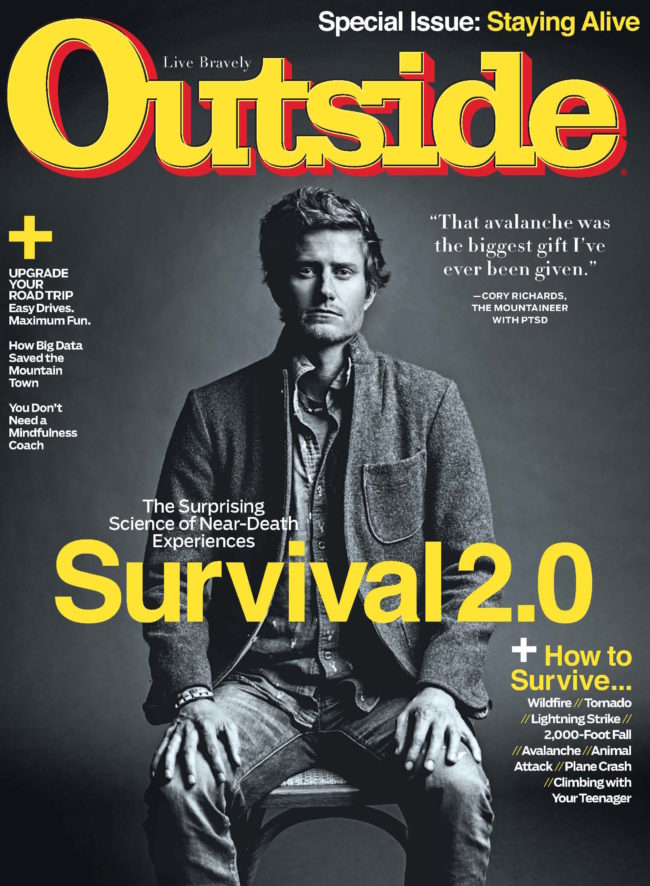

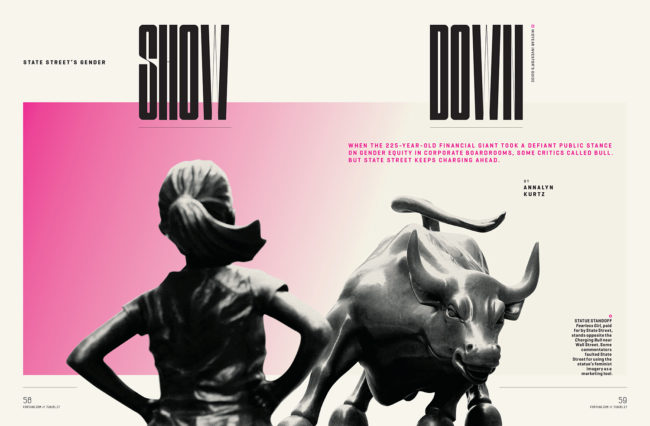

John Huet’s iconic sports photography is included in both shows, as well as in the book, “Who Shot Sports”. This terrific book by Gail Buckland accompanies the exhibition and chronicles the history of sports photography from 1843 to the present.

I got a chance to connect with John about this work, his affinity for #theartofsportsphotography and the genesis of his Olympic odyssey.

Heidi: I haven’t seen much of your work on Instagram, and it’s been such a treat to see all the images you’ve been posting recently.

John: Thanks, Heidi. Part of my thinking behind the posts I’ve been doing was to share my enthusiasm for having my work in the two shows at the Olympic Museum and in the book “Who Shot Sports”, which are all part of the museum’s celebration of sports photography this year.

I wasn’t going to get to Lausanne for the opening of the exhibits in May because I was somewhere else on the planet so I thought I would bring the show to people via Instagram. That’s sort of where the thought process started. Because the show was running through the summer, I thought I’d make this “The Summer of Sports Photography.” I started posting daily on the Summer Solstice and continued until the Fall Equinox. The hashtag #theartofsportsphotography is actually the overall name of what’s going on at the Olympic Museum right now.

I noticed that # on your feed actually, so that’s why I was really curious about this new initiative.

I don’t think it was for any purpose other than I really like the idea of “the art of sports photography”. I’ve always liked the idea, without having put a name to it. I don’t think that sports photography gets the recognition it should. Of course, that’s coming from a person who shoots a lot of sports, but it’s funny to me that sports photography is rarely a category in photo competitions, and God forbid that there would ever be a museum show featuring the work of a sports photographer. It just doesn’t happen, and yet sports photography is an art in which the “decisive moment” is captured in a nano-second, and I can’t think of any other area in photography where the general population, the media and advertisers/brands alike rely so heavily on imagery. It’s a multi-billion dollar-industry that’s basically been created by the images that photographers have made over the years, and still it somehow isn’t recognized in the same way as other genres of photography.

So, when Gail Buckland decided to do the Who Shot Sports exhibition and accompanying book, I thought it was the greatest thing ever! Finally! And what she curated is just fantastic, I can’t recommend the show more highly. You don’t even have to be a sports fan, there’s just so much there to see. Photographs that you can look at and just enjoy as a photograph and not because it’s of a basketball game, or some sporting event, or a portrait of an athlete. It’s just beautiful photography and that led me to want to show more of my own work using #theartofsportsphotography. To be honest, I was hoping that other photographers would join in, using the hashtag on their images. There are so many great photographers out there shooting beautiful sports stuff, and it would be cool to have a collection of images on Instagram from a lot of different people using the hashtag. A few people joined in but not as many as I’d hoped.

Instagram is a funny thing; it’s timing, and repeatability is very important. If this hashtag is something that you really want people to use, you can just suggest it to people, I think there’s always a camaraderie in creative people. I suspect people didn’t use it simple because they’re not reading. Everybody is looking when they should be understanding the context as well.

At the beginning, I actually wrote more about the photographs themselves, and then when I’d talk to people about it, they’d be like, “Oh, you wrote that?”

I read all your captions because I think it’s what sets people apart, when there’s more content.

I agree. I definitely wanted to point out what cameras I was using, where the image was shot, and who it was for. I use a ton of different equipment, and I try not to get too repetitive, if I can help it, so it was good for me to look back and think, okay how did I shoot this? What did I shoot this with? It was a great exercise for me.

It was also good for me to go back and look at photographs that I hadn’t seen in a long time. And it’s been really nice to read comments from photographers whose work I really respect. We work in such a vacuum, which makes me really appreciate the acknowledgement and respect of my peers.

You have deep roots with the Olympics with your first assignment coming from the Salt Lake Organizing Committee in 2002. Can you tell us how that materialized?

The Salt Lake Olympics, that came about like many things for me – in a random phone call. The Director of Creative Services for the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) saw a few images in the Communication Arts Photo Annual and called to ask if I would be interested in doing some work for them. Little did they know I’m a closet Olympic freak and have loved everything about the Olympics since I was a kid. I don’t know why, I just couldn’t watch enough of it growing up.

They flew me out to Salt Lake the next week, and we talked about what they were looking for as the run up to the games, which is basically how an Olympic city is decorated for the games. Each Olympics has a color theme and slogan; theirs was “Fire and Ice,” and we came up with the idea to decorate the city in a particular way, so that when NBC had that opening shot of the city at night, the audience would see the skyline of Salt Lake City with those beautiful mountains in the background.

We decided to wrap the 17 biggest buildings in the city in photographs. We spent two years working on computer models to help us make all of our creative decisions. We finally decided to use 17 different images, based on each discipline at the Olympics, ultimately giving each discipline its own photographic logo. The images had a similar tone, color palette and background. In addition to the building wraps, the images were all over Salt Lake and Park City – in the airport terminal hallways, at baggage claim, on the city buses, on the light posts, and at the Olympic venues, of course. It was incredible.

But things didn’t stop there, SLOC wanted me to shoot the games themselves, and they asked me to shoot the commemorative book for Salt Lake, “The Fire Within”. The host city for each Olympics produces an annual report after the games are over. It breaks down every detail about how the games were put together: the venues, the costs, the attendance. Everything right down to how many plastic spoons and napkins were used. The amount of information that’s generated for the Olympics is staggering.

It was obvious that one photographer couldn’t possibly cover everything that would be happening, so we discussed involving several photographers, and that’s when I came with that idea that I would bring in photographers who may have never shot sports or been to the Olympics. I thought it would be cool to work collectively with a diverse group to shoot the commemorative book.

When all was said and done, we had a broad spectrum of 12 photographers, ranging from a 19 or 20-year-old photographer to Shelia Metzner, a fine art and fashion photographer who had never shot a sporting event in her life.

David Burnett was the only photographer with experience at the Olympics, and we knew that he would deliver great images in the way that only he can. Michael Siemans, a photojournalist from the Boston Globe, was someone I struck up a conversation with during a rain delay at a Red Sox game, and he became part of the team.

What was SLOC’s direction for “The Fire Within”?

For us, for me, the direction was to create a commemorative book that would show the Olympics in a completely different way. They did not want straight up sports journalism; they wanted Olympic images that had never been seen before. They wanted art, and the only way we could deliver what they were looking for was by having access to areas that were off-limits to press photographers.

During the project, we had four photographers with the kind of unprecedented access that hadn’t been granted since Leni Riefenstahl shot the 1936 Olympics in Berlin for Adolph Hitler. There was one point when I was photographing the start of the luge, and the NBC cameraman was behind me. I heard him say, “there’s some photographer in front of me. I can’t go down any lower. No, we can’t move him. They told us he’s allowed to be there.” I had to smile at that point.

The experience itself was great. Working with all of the different photographers, it was awesome, and everyone was extremely happy. Some of us were working with large format antiquated cameras, hauling them up the side of a mountain and having photojournalists just shake their heads at us like we were crazy. Some of us were shooting Polaroid negatives. Holgas were being used. Raymond Meeks, who is an incredible fine art photographer, set up in the Olympic Village and was photographing the athletes using hand-coated glass plate negatives. They are some of the most haunting and beautiful images I’ve ever seen. It was an incredible adventure, and I can think of no better way to start my Olympic odyssey.

So then, how did your relationship with the games grow and develop after that?

The next Olympics was in Athens in 2004. This was my first summer Olympics, and I was hired directly by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). I covered the 2006 Winter Olympics in Torino for ESPN the Magazine, and I’ve been shooting for the IOC since the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Shooting in Torino for ESPN was a whole different world. I went as a straight-up photojournalist with a straight-up photojournalist credential. That’s an interesting thing.

Interesting how?

Mainly because of the limitations that come with those credentials. In Salt Lake and Athens, I pretty much had full access to anything. That had been my experience, then all of a sudden, I had restricted access. It required a shift in my approach. That said, working with the photo managers was so helpful. Before then, I never worked with the photojournalists or the photo managers at the Olympics. I was on my own; and now, working with these guys, it was great because they did such a great job with getting the press what we needed.

At this point, you’ve shot the Olympics in the U.S., Athens, Torino, Beijing, Vancouver, London, Sochi and Rio. What are some of the cultural differences that you experience, and how do they inform you?

The culture of each host country is very much represented at the Olympics, particularly in the Opening Ceremony and the Closing Ceremony. I’m always interested to see what a country will showcase at the ceremonies, but so much of the experience for me comes down to the local people. The volunteers that work at the games are just so happy that the Olympics are there, and they’re very proud of the fact that they’re a part of it. They’re proud of their country; they want to show it to you, and they want to help you. Overall the experience has been amazing, and the people have been awesome. That’s saying a lot, as I’m about to go to my ninth Olympics.

So speaking of your ninth games, what are you– how do you stay engaged in it, and what are you hoping is going to be different? Or what can you tell us about the upcoming games in PyeongChang?

Each place is different both culturally and visually, and each event has been unique. Just being in a foreign city can make something that you’d think would seem similar feel entirely different. And while the Olympics are the same event to a certain extent, the actors and the stage are always different. I try to tell the broadest story I possibly can, and what gets me excited about PyeongChang is thinking about the stories that are waiting to be told, the ones that haven’t happened yet.

There are surprises at every Olympics; the story of what’s happening changes all the time. Sometimes the weather creates a scenario that you can never predict, but you have to always be prepared for, sometimes it’s the emotion of a particular country having an athlete cross the finish line for the first time in its history, or it can be that an athlete who isn’t on anyone’s radar ends up winning a medal. There’s always a new story to tell.

I was covering the Australia vs New Zealand finals of the first ever women’s Rugby sevens in Rio. I had done setup rugby shots for advertising in the past, but I had no idea what the rules of Rugby Sevens were. Luckily I was given a great introduction by the South African coach who took the time to explain everything to me when I photographed a training session with his team the week before.

So I had a new story to tell. Not only was this the first event of its kind at the Olympics, but everything about it was new to me, and this game is just non-stop, fast action with teams made up of seven players playing seven minute halves, instead of the usual 15 players playing 40 minute halves. It’s impossible to not be fully engaged when shooting a game like this. Before I even start shooting – I’ve got to decide where to position myself, and I’m constantly accessing what’s going on with this game that’s not familiar to me. Then, if I’m not getting the images that I want, I need to move to another spot where I can get them, and I need to do this as fast as possible.

This particular game was really intense. There was a controversial call in favor of Australia which swung the momentum of the game, and in the end, Australia won. The New Zealand team broke down in tears. The emotion was just overwhelming.

Fast forward 10 minutes, and the losing team in any final competition at the Olympics is expected to be at the podium to receive their medal for losing a game that they’ve trained for for years. I know it’s not really thought about that way, but I’ve watched this so many times, and I just see how hard it is for these teams to play with everything they’ve got up to the last second, and when they lose, there’s no time for them to process that before they have to be on the medal podium. At that time they usually don’t see it as, “We won the silver medal, that’s good.” They see it as, “We lost the gold. That sucks.”

So after the game was over, all of the photographers, all of the press photographers – got lined up, and there were probably 200 Olympic staffers there getting ready for the medal ceremony. Both teams had entered the field, and they were looking out to where the podiums were being put up. The Australian team was milling around, and the New Zealand team was doing the same, but they were all in tears. They were just heartbroken. As I walked over to stand behind them, all of a sudden, the crowd in the stands started to chant the haka, the traditional war cry from the Māori people of New Zealand. There’s a lot of cultural meaning and symbolism to the haka, and the “All Blacks”, New Zealand’s rugby union team, have been performing it before games to intimidate their opponent since the early 1900s.

This is one of those times when the story of what was happening, the medal ceremony, changed completely. I turned around, and I saw all of these big dudes in the stands, all standing up with their shirts off. They were sounding off this tribal chant that I’ve seen on television, but now I was 10 feet away from it. I started taking pictures of them, and I was turning and taking pictures of the New Zealand women’s team reacting to the men in the stands, and back and forth, and then the women just formed into this group. There was no gesture or comment or anything. They just formed this group and started to do the haka back to the people in the stands.

So there these women were with tears coming down, and they were doing this chant with these intensely aggressive eyes, and I couldn’t pull cameras up fast enough to take pictures; close ones, wide ones. I was doing everything I possibly could, as all photographers do, to capture those moments as fast as I could, and I kept looking out of the corner of my eye wondering, “Is anybody else taking pictures of this? Am I the only person taking pictures of this? This is awesome.”

That was a gift, and it was just incredible to be standing where I was and to be able to capture that experience.

Below are links to John’s 2016 Rio Olympic Galleries.