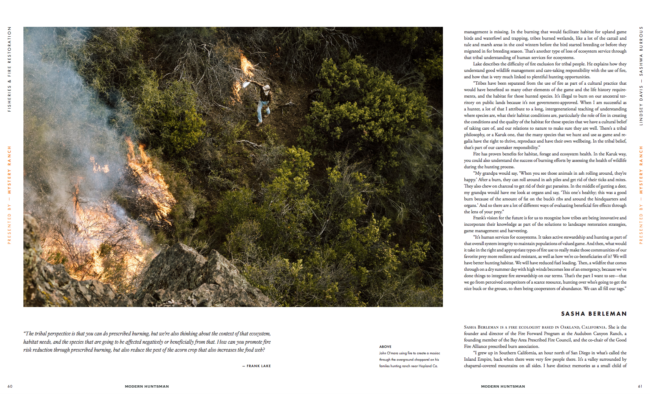

Photo by Nipah Dennis

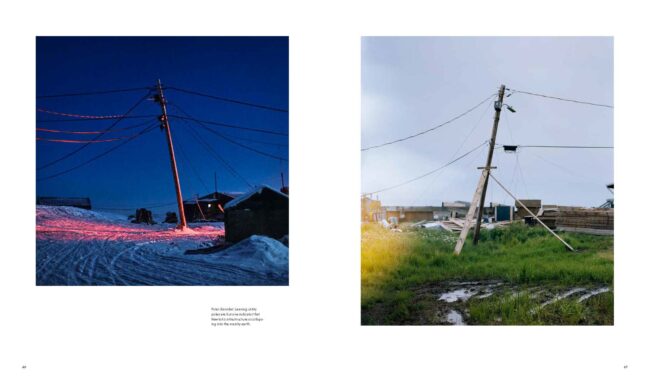

Photo by Terra Fondriest

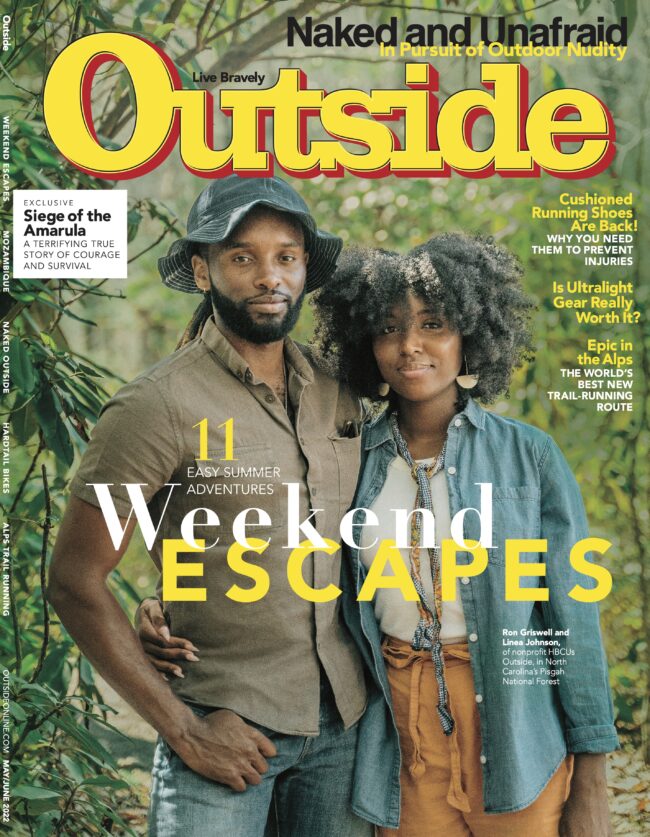

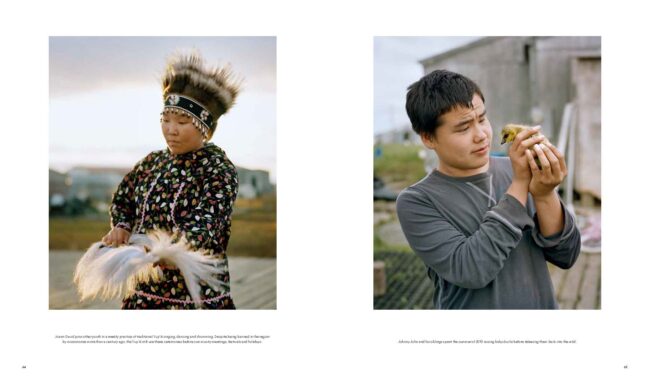

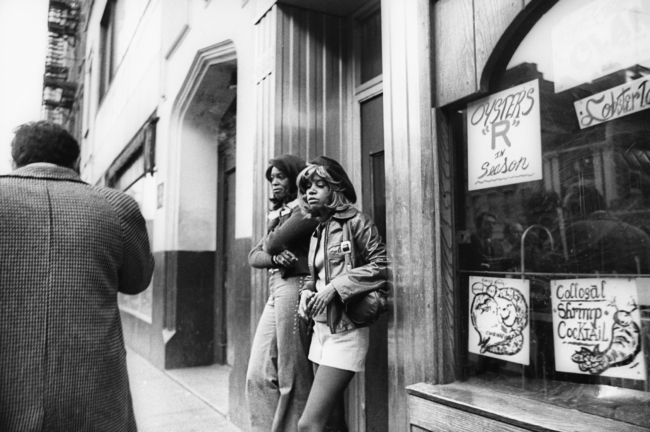

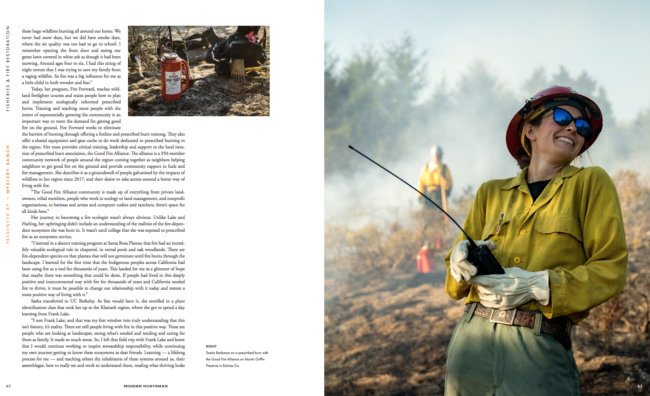

Photo by Linda Kuo

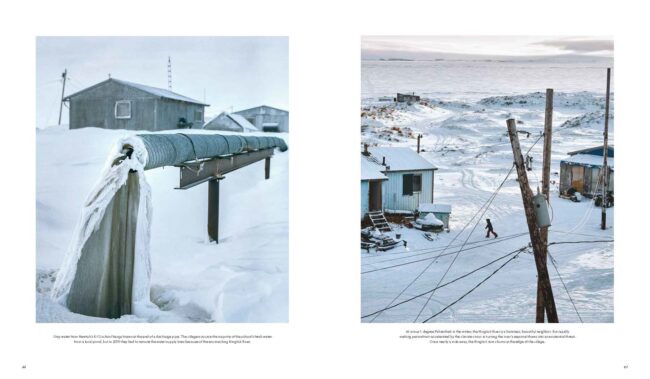

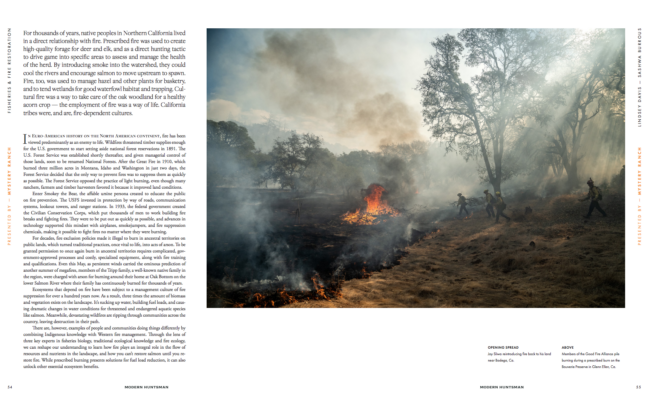

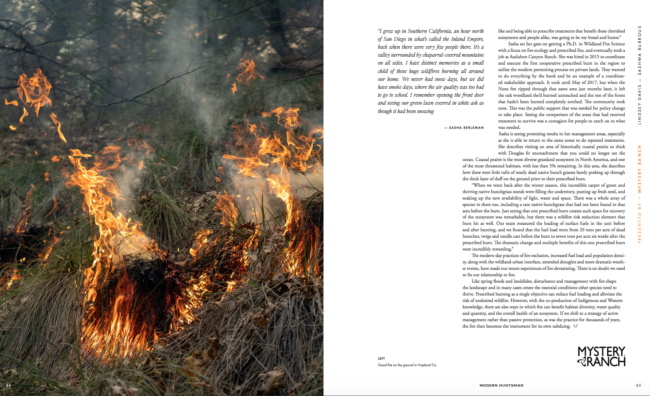

Photo by Karen Toro

Photo by Karen Toro

Visura.co

Founder: Adriana Teresa Letorney

Co-founder: Scout Film Festival

Heidi: How long has Visura been publishing and how has the last two years informed how you’ve run your business?

Adriana: Visura was launched in 2016 as a networking platform for freelance visual journalists to build their online presence and connect with each other from one central place. The tech platform was built from the ground up as an alternative to the traditional systems used by visual journalists looking to connect with the global marketplace. During that time, the main problem we were aiming to address was the lack of platforms for freelance visual journalists worldwide that fostered inclusivity, sustainability, professional skill development, and equal and merit-based access to the global marketplace.

In time, editors wanted to use the platform to search, view stories, and directly connect with freelance visual journalists who were part of the global Visura community. This led us to also create an Editor’s account for visual researchers, editors and buyers to be able to search, connect and manage a growing list of freelance visual journalists and storytellers based on location, expertise, skills, and experience.

Our goal has always been to elevate media literacy by empowering a growing global community of publishers and freelance visual journalists with a central platform where they can connect, share work, and transact. During my studies, I learned how technology plays a significant role in the market of visual content. and ask these questions: Will this tool unite or divide? Is what we are doing fostering understanding and empathy, or inciting division? Is our service empowering or exploitative? Are the resources we are offering solving a problem for our community?

These questions leave room for debate, opportunity to connect with new thinkers, visionaries, leaders, and professionals looking to tackle some of the biggest challenges in media and journalism.

What were your hopes coming to New York from Puerto Rico?

I was born and raised in Puerto Rico. I came to New York with the dream of offering new perspectives about what it means to be Puerto Rican. I thought what I saw in the news or in films was biased and unfair. Never in a million years did I think I would build technology to tackle discrimination in the media and journalism industry. I was just a kid that loved being from Puerto Rico, and I thought, if the world had better access to the incredible work and talent that is being produced in my country, people would change their minds about who we are. I never imagined that my concern was a global problem. As soon as I realized it was—I chose to dedicate my professional career to tackling the systematic challenges that lead to more discrimination, abuse, biases and violence. And since, I have found hope in dedicating all these years to finding ways to empower the freelance community of visual journalists and storytellers, who just like me, want to share their stories and findings to offer new perspectives.

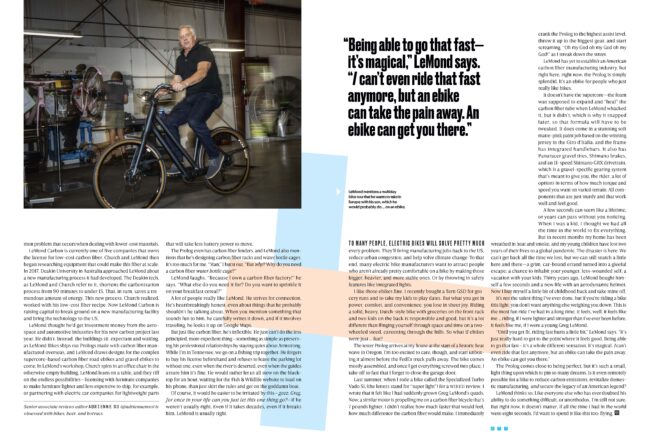

Your site has robust features such as maps and directories. Did you always have an interest in technology?

To be honest, I learned to use tech to solve a problem. And most of what we have developed was created by years of customer discovery. At Visura, our team serves its community. I don’t have a light bulb that turns on with some magic solution. Everything we have built has been the result of listening to understand our community, and their needs, we are thankful for community.

How and when did this idea come about, did the Scout Film Festival come shortly after?

Prior to Visura, I had launched an exhibition space, a magazine, and a self-publishing platform with a goal of highlighting a growing community of freelance visual journalists and storytellers worldwide. By the time Visura.co launched its first version in 2016, I had learned from the community of primarily freelance photographers from around the world that what they needed was tools to build their website and connect with the global marketplace to further their work and career. So, we worked really hard to build this for them.

Scout founder Anna Colavito and I met in 2014 at an Art Gala event. She shared with me the idea of launching a nonprofit organization called Scout Film Festival that aimed to support teen filmmakers. I loved the idea, and overnight we decided to join forces to realize her vision. When it launched in 2015, I joined as co-founder of the 501(c)3 organization. Throughout the years, Scout has evolved into an international festival supporting filmmakers aged 24 and under with resources, tools and opportunities to highlight their short films and further their careers.

Scout specifically highlights artists under 24, why is that?

That’s a great question! At the time, Scout became the first festival focused on emerging talent. Initially, we began by supporting teens. With time, we expanded the community to include college students because many of the initial filmmakers were aging out, and they expressed wanting to remain a part of the community as undergraduate students. So, we expanded to welcome filmmakers aged 24 and under. In the future, we hope to continue expanding further. Ultimately, the mission of Scout is to support, empower and connect diverse filmmakers worldwide. Throughout the years, the organization has become a premier destination for the professionals in the film industry to find new talent, particularly directors, screenwriters, and producers.

There are several collectives that emerged this past few years, what makes this one different?

Visura is not a collective. Visura is a market network that leverages technology to empower a growing community of freelance visual content creators with tools to manage their online presence and connect with the global marketplace. The way we envisioned the tech that would power the platform stems from our belief in the power of community. So, we are a media-tech platform that fosters professional development, inclusivity, equal and merit-based opportunities, enabling environments for media and journalism.

At Visura, professional photographers, filmmakers, photojournalists, journalists, arts, and other visual content creators can build their website interconnected to a networking platform that is used by editors, researchers and buyers to discover new work and talent. The platform is proprietary. It is not built on Squarespace or WordPress, or any of those platforms. We built our own technology platform to better serve our international community with the tools they need to connect, collaborate, and in the future transact.

Visura also offers editors access to exclusive stories, lightboxes, advanced search, image briefs, maps, and other tools to search by location, skills, expertise, and experience. More importantly, editors have direct access to a database of over 6000 professional visual storytellers worldwide. Any editor can access the creators’ profile which highlights their bio, contact, website, social media links, clips and samples of their work. They can contact the members or save stories or profiles in lightboxes for future references.

Sustainability goes beyond making lists, how are you creating a sustainable way forward?

Absolutely it does. I believe that the Visura platform serves to bridge the gap between visual content creators and buyers, and it does so in a way that does not exploit the talent or their work. This is very important. We are also very focused on streamlining merit-based opportunities. Quality is never at risk when you create an inclusive work environment. On the contrary, it elevates and enriches the space. And as a female woman of color, I strongly believe that publishers will further grow engagement if they can easily connect with a global community of professional visual journalists and storytellers ready to be hired.

How can I join as a contributor?

Start with a free account or download the Visura App that is now available on the Apple Store for free. Upgrade if you want to submit exclusive stories to the archive, or build one or more websites via Visura.

How do I join as an art buyer?

Start by requesting an account, to access the advanced search, exclusive stories, contact info, lightboxes, and brief tools, amongst other things. Then download the Visura App that is now available on the Apple Store for free. In order to protect the community from spammers and hackers, editors need to request an account.

How can access make a difference and what are your hopes for the future of the industry?

There is a lot that we need to do to empower the media and journalism industry with better systems to power the marketplace. Over 70% of visual storytellers today are freelancers, publishers need better access to this incredible talent pool and we need to think carefully about how we approach these issues.

Over time, we’ve seen that relying on social media or spreadsheet lists as the primary solution to highlighting talent is unsustainable and in the long run, ineffective.

We need solutions that unite and foster career growth versus what is a marketing or social media strategy that serves the organizers in the name of “community”.

With a conglomeration of information, audiences demand authenticity and truth in content without being “sold to.” As a result, publishers are realizing the value of unique, in-depth, and compelling visual stories by diverse visual storytellers worldwide. We learned that in order to facilitate better access to quality visual content, we needed to re-envision the systems that power the marketplace and create access for breaking news, stock, and unique visual storytelling.

90% of the information that the brain retains is visuals; and publishers grow engagement much faster when they feature unique, compelling visual stories. I foresee that freelance visual journalists will hold the power in the future of this marketplace.

We strongly believe that technology can facilitate the tools they need to manage and grow their career. The best path forward is removing the gatekeepers and giving power back to the creators with a toolset to manage their online presence, connect, get hired, and sell their work.

I don’t have all the answers. I have failed much more than I have succeeded. But at this stage in my life and career, I am on a mission to continue finding ways to re-envision the marketplace and future of media and journalism