Newtok: Patagonia Journal and film

Photographers: Andrew Burton and Michael Kirby Smith

Heidi: Why was it important to you both to make this film?

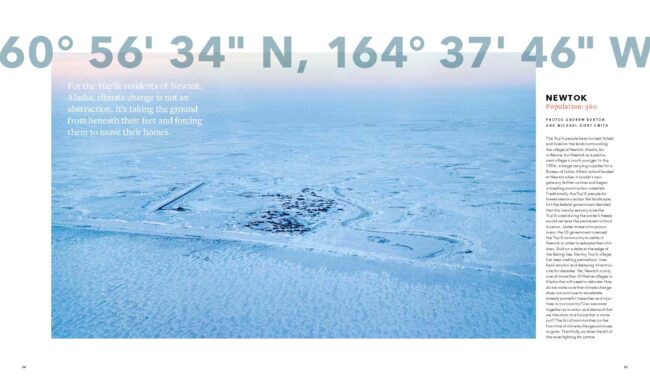

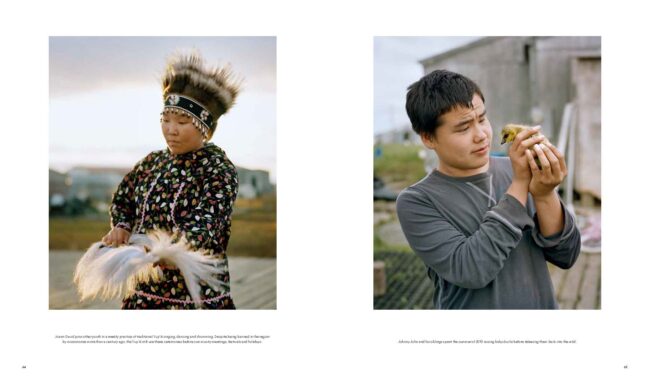

Andrew and MIchael: We set out to tell the story of Newtok, AK, in 2013 because we were tired of the overly simplistic media narrative that climate change was something happening in the future, predictive in nature, affecting generations down the road. We felt the story was happening now across the globe and in the United States. It was important to us that we found a story in our country after reporting abroad. When you start to look at stories in America impacting citizens here you quickly find Newtok. In news, the media often distills stories into simple digestible narratives and the more we learned about Newtok, especially after our first reporting trip, we quickly learned that the story is very complex, nuanced, with a beginning that dates back further than we could have imagined. We didn’t want this crisis to be portrayed through cliched and stereotyped imagery, such as a sad polar bear or melting glacier, knowing that this is not where we’re at with the climate narrative. Newtok’s story is complex, which in a way is representative of the larger complex issues when discussing the climate crisis in the sense that the narrative, and possible solutions do not have easy answers. The crisis is here in the U.S. happening today, to our fellow citizens, and our goal was to tell a story that immerses the viewer in the emotionality of this unfolding catastrophe.

This project was seven years in the making, how much photography and motion did you collect and what are your hopes for it beyond this feature film?

The project has grown into a much larger body of work. In a lot of ways the project’s growth was very natural in the sense that when we first started we were really reporting by taking pictures, writing, and documenting anything we felt was relevant to better understanding the story’s complexities. It’s now turned into a behemoth body of work that has been overwhelming at times. We filmed 130 terabytes of footage from 2015 – 2020, including hundreds of rolls of film and 20,000+ digital photos. In collaboration with the village and with their expressed permission we’ve collected old family photos, home videos, archival documents, maps, etc. We’ve handed out 70+ disposable cameras to the community for them to document their relocation and had kids fill out surveys about what they think of the relocation. Newtok began in 1949, under forced federal mandate, and according to the land exchange deal everything must be deconstructed in Newtok and handed back to its natural habitat. Because of this we do feel a certain obligation to document this entire process, especially since this is one of the first communities impacted by the climate crisis. The film is part of that ongoing body of work and our ultimate goal is to have an expansive multimedia document of a place that will not exist down the road. We want to create an archive which includes a documentary film (coming out April 22), a photo book, an online website, and a traveling exhibit. Eventually, with the blessing of the community, we’d like to see the entire body of work donated to a museum or university archive, but we still have many years ahead knowing the relocation is not complete.

The past four years have been dynamic to say the least (politics, the pandemic) how did that impact your project?

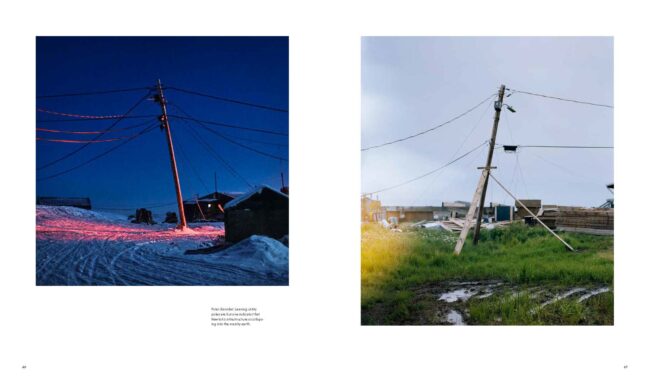

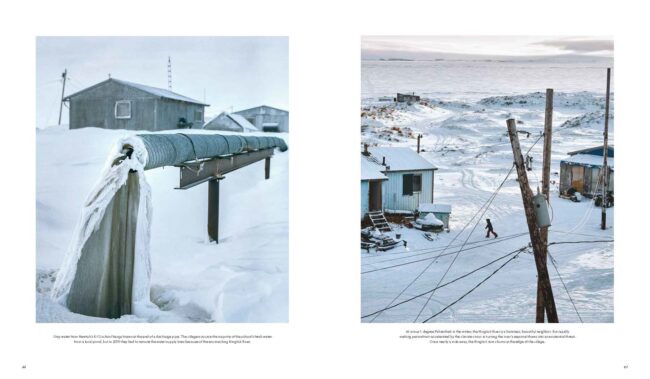

Like everything impacted by the pandemic it’s been really tough. Covid has kept us from traveling to the village for two years (2020-2022) which was the longest we’ve been away from the community. It’s also disrupted our ability to screen with the community in the way we’ve always envisioned, but with that said, there is a lot of understanding of the obstacles we’ve faced in this regard. We spent much of that time editing the film and getting it out into the world. Beyond covid, this project has now been through the Obama, Trump, and Biden administration. What is remarkable is all the lip service and attempts to help the community from 40+ state, federal and nonprofit agencies, and all bluster of partisan politics, how remarkably little has changed in the village. It speaks to how complicated it is to navigate climate change politics in the current state of our country’s political stalemate in writing meaningful policy. Other than the big surge of funding in 2019 which moved 1/3 of the community, the majority of people still live in Newtok. So now you have a situation of a divided community which is tough for everyone. The goal is to remain together as a community in a safe environment and that has not happened. The river is still eating away at the shoreline, funding is not secured, and the community continues to fight for relocation while struggling in living their lives because of degrading conditions and families torn apart. Covid had the biggest effect on our ability to work on the story, but beyond that, the situation in Newtok is still dire and very real.

How did this self-sustaining community influence you as a parent, citizen, and creative?

As journalists we try to keep our personal baggage away from conversation, but in the context of process and longform storytelling, there is value in discussing this more as a way to encourage other filmmakers and journalists, and to just personally reflect, which is always good. To begin, throughout the making of the project we have had monumental personal change and professional growth. How we would begin to tell a story of this nature now looks different than how we did and that’s rooted in learning and growing as individuals and as a team. That doesn’t necessarily mean we would be telling a different story either. Personal life, all the ups and downs while working on a project like this continue, and the inherent difficulty to navigate individual stress is amplified in long form independent storytelling. You don’t have the same institutional support, in terms of financial help, which makes it harder to justify an undertaking of this nature if you are reliant on freelance income, as we both have been throughout this process. This means you really have to believe in the storytelling process where you find yourself somewhat blind to what awaits in terms of success, both editorially and financially. That’s really tough and stressful. What the community has really taught us is the value of being more present minded in general and how to find hope and joy in the face of struggle and overwhelming odds. In a lot of ways this informs everything in terms of the filmmaking process. This has made us better communicators with each other, and strengthened us as a team. We’ve been taught values that come out of a small, tight knit community and family – emphasizing forgiveness and love no matter what. The community has also taught us what real sustainability and self reliance look like – of knowing the landscape and ecosystem and weather patterns and nuances of your land. What incredible beauty and lessons we have to continually learn from this symbiosis. The project has taught us to be open and collaborative and that good storytelling takes a lot of time that can’t be forced. It’s almost as if each story has its own temporal governance, that you have to learn and adapt as a storyteller in order to fully realize the potential of the story, and that the story will unfold in its own rightful time. It has entirely and holistically changed the way we will approach future projects, and we are indebted to the community of Newtok for teaching us better awareness, which we grow from for the rest of our lives.

The community of Newtok trusted you both to tell this story and invite you into their homes and lives, what were some of the pivotal moments of trust building?

It’s been a real honor getting to work with the people of Newtok on this story, and this could not have been done without our producer Marie Meade. Bringing her into the field was a seachange and a huge moment in transforming the story and gaining trust from the community. Marie is a highly respected Yup’ik elder, and leading Yupik anthropologist, author, linguist, and scholar, who is an incredible teacher both in an academic setting as a professor, and outside of one. She has direct familial roots to the Newtok community, specifically her family lived in the village of Keyaluvik where the people of Newtok were prior to forced relocation, but she had never had the opportunity to visit when the community was divided. This was very serendipitous for the project, because working on the film offered her an opportunity to visit with extended family and see her ancestral lands. So, our team not only had a known Yupik educator and leader come onboard, but someone who had personal connection to the land and people of Newtok. It’s impossible to quantify the value she continues to add to the project, we can only say that it wouldn’t be close to what it is today without her agency and insight into the community. She is someone who has devoted her life to better understanding her own heritage and has been instrumental in preserving the Yupik language and culture for future generations and she has given us leadership and guidance through the making of this film. We adore Marie.

The second, pivotal element that comes to mind, is much broader and came through by time on the ground just continuing to show up to the village, and reiterating our intention to try and get the story right. The community has seen a lot of parachute journalists, filmmakers, photographers, and tons of nonprofit and government agencies on top of that. They’ve become wary of outsiders for good reasons. People don’t often present their intention to the community, or get to know people and listen, so it sets up a potentially exploitive result that sours community perspective. We’ve now logged more than 300 days in the village and know folks there intimately, and we have been granted access by the community’s leadership by trying to be transparent and open about our intentions. What began as distrust has evolved in time to an alignment of intent, which is to bring attention to the traumatic disaster unfolding. Time has given us the opportunity to learn from the people of Newtok which is instrumental to the storytelling.

You are both photojournalists, how did this project reinforce / continue to inform you both that this work is essential in an age of misinformation?

This is a very complicated question to try and begin to answer. People are aware of how news consumption has drastically transformed in the digital era with social media platforms abound, but we still don’t know what the implications are on society and what that means for the future of documenting history if journalistic guidelines lack clarity. The journalism transformation is happening so fast that we can only speculate. There is incredible work analyzing this stuff, but it’s mostly in a slower moving academic dialogue, and while that is being pondered journalism’s voice to tell stories is being diminished. Photojournalism comes from a lineage that has journalistic guidelines and principles, as an example, actually being transparent in the journalism methodology itself. These ethics were traditionally shaped and defined by legacy journalism institutions and publishers, which have been folding throughout the country and world. What has risen in the wake are numerous platforms, and even forms of storytelling, that have no clarity on the code of ethics in reporting, fact finding journalism, and publishing. Photojournalism remains essential because the intent is clear and the methodology is clear. The struggle now is there are fewer platforms for publishing the work which makes it extremely difficult to have a career which is a great loss to journalism in general.

The community is in a constant state of migration: homes they grew up in, their land, culture and tradition. How did this project make you rethink what it means to be home?

This project made us reconsider the definition of home in a visceral, tangible way, that it is more than just a physical structure as we have perhaps defined it prior to the project. The definition is different across cultures, and for the community of Newtok “home” is more than simply a house, or the village itself – it includes the ecosystem that provides subsistence life. It is a much broader swath of the Yukon Kuskokwim delta, where, for millennia, they have moved between seasonal hunting grounds, a migratory understanding of the word.

There is an argument made by some fiscal conservatives that it is too expensive to relocate communities like Newtok and that it would be cheaper and easier to simply offer a buyout to residents, forcing migration into a major town. This argument hinges on a limited western definition that a home is definable by a four-walled structure, or version close to that. Such suggestions lack ethical consideration especially considering the community of Newtok only became attached to western infrastructure under forced mandate by the same government that would be suggesting a buyout. The fact is, to move a native community like Newtok, that has chosen to remain on their ancestral lands and disperse the community into a larger city would result in the opposite of “relocating their homes.” It would be the destruction of their lifestyle, their culture, their way of life and is genocidal by nature.

How did the community receive the film and how can folks give back or get involved?

We began showing the film to the community in stages. First, while we were still editing the film, we began showing rough cuts to our advisory board – a group of people made up of Newtok community members, a local journalist who worked in Newtok, a Yup’ik philosopher, a Yup’ik anthropologist, a project manager on the relocation and a member of the Smithsonian institute. After we received notes from the advisory board and incorporated their thoughts into the film, we showed the film to the people depicted in the film and had conversations with them. Throughout this process our aim was to make sure we were getting the story right, being culturally accurate and culturally sensitive and to learn about our inevitable blind spots. Then we showed the entire community of 400 people the finished film. We’re humbled, grateful and proud to say that the community has been very complimentary of the film.

How difficult was it to use your equipment in the elements?

Operating in Newtok was never easy – we were exposing our gear to -40 degree winter snow storms, giant Bering-sea storms, salt water spray, mud, muck and moisture. We demanded a lot of our gear and ourselves (frostbite while changing rolls of film isn’t fun to deal with). To the camera manufacturers unending credit, we never had any issues with our cameras – they worked amazingly well throughout the entire production.

What were the advantages of being a crew of two?

Photojournalism puts a lot of focus on the individual – one byline, one person, one credit, and filmmaking is so collaborative by nature. There is strength in numbers and we really wanted to collaborate on a project and move towards a team approach. The process of that had a lot of growing pains and forced us to really listen and rely on each other in a way that is really incredible when you start finding the cadence of that other person. We often joke that our personalities are so different to the point of describing it like we’re ascending the same mountain on different routes, but there are real advantages to the differences once you fully trust each other’s approach, and how our process differs. At the end of the day we usually always land in the same place, in agreement, and along the way we have grown as collaborators and friends. We learn from each other and believe that by working as a team, the final product is greater than the sum of the individual parts; a sort of 1+1 = 3.

Tour dates here and see how you can support climate justice.