“I’m just trying to understand it, Mother.”

“What is there to understand? Just read it. There it is in black and white. Who wants you to understand it? If the Lord God wanted you to understand it He’d have given you to understand or He’d have set it down different.”

John Steinbeck, “East of Eden,” 1952.

Have you ever heard of Andy Kaufman?

He was a comedian back in the 70’s, and got famous for pissing people off. (And for his weird-ass accent in the TV show “Taxi,” which would certainly be considered offensive in today’s cultural climate.)

I must have seen a few minutes of his stand-up act, back in the day, and then Jim Carrey played him in a movie, but I do have strong recollections of his place in the culture.

Andy Kaufman was such an absurdist, he’d get on stage and say strange, not-particularly-funny shit, just to get a rise out of his audience. Some of it was hilarious, but mostly because he was toying with expectations in a manner that feels very of-the-moment.

I’m pretty sure he got involved with professional wrestling, and got his ass kicked for real, because he made his living pushing the envelope.

Plus, he did a spot-on-perfect Elvis impersonation. (And got to hang out with Johnny Cash on “Hee Haw,” which melts my brain.)

These days, we know all about trolls, and gas-lighting, but it seems Andy Kaufman helped pioneer the practice, back when it would have seemed revolutionary.

To me, the point is to grind into the human consciousness that our desire for things to “make sense,” and for us to be able to “understand” the world, much less the Universe, is hubristic and fallacious.

Much like Loki needed to get the shit beat out of him by Hulk, in my kids’ favorite scene in the first “Avengers” film, Andy Kaufman was the canary in the coal-mine for our 21st Century misadventures. (He died young, and didn’t live to see our new-times.)

Poor guy.

At least he had some fun.

But today is not one of those days where I’ll weave together ten strands of American culture into a tapestry of awesomeness. (Sorry if that sounds cocky, but sometimes I get there.)

No.

Not today.

I’ve been immersed in trying to reason with a teenager, who’s been hell bent on self-sabatoge, as were millions of teenagers before him.

Trying to understand the teenaged mindset, from a 47 year old vantage, makes about as much sense as a chicken trying to force its way into a KFC. (A true story I heard on Sirius radio the other day. Dumb fucking chicken.)

Today, I’m going to cut to the chase more quickly than normal, and the connection between the introduction and the book review will be as obvious as a wet-dog-fart.

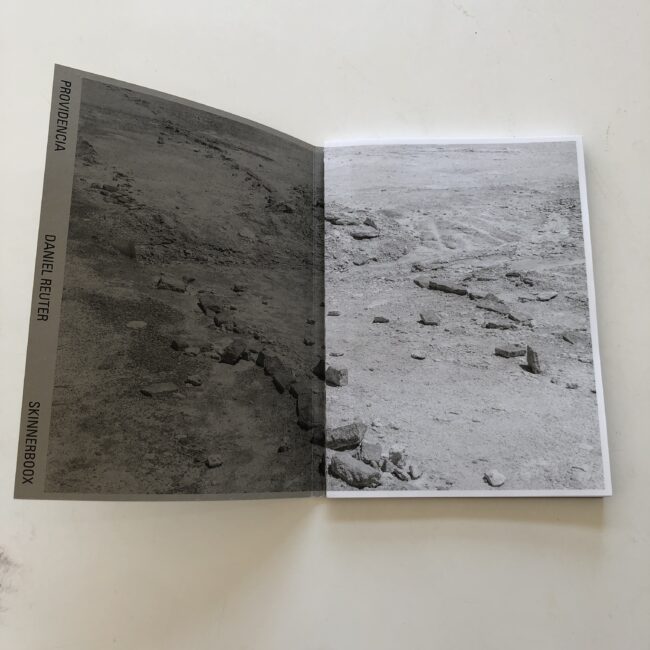

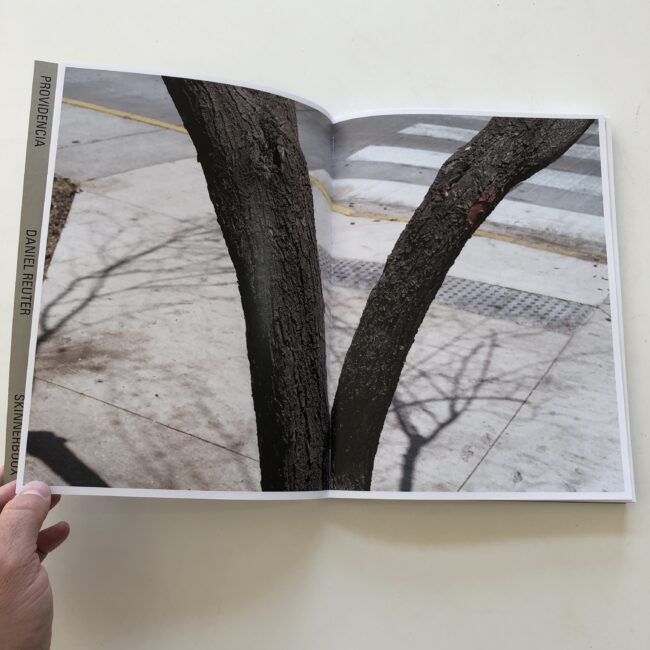

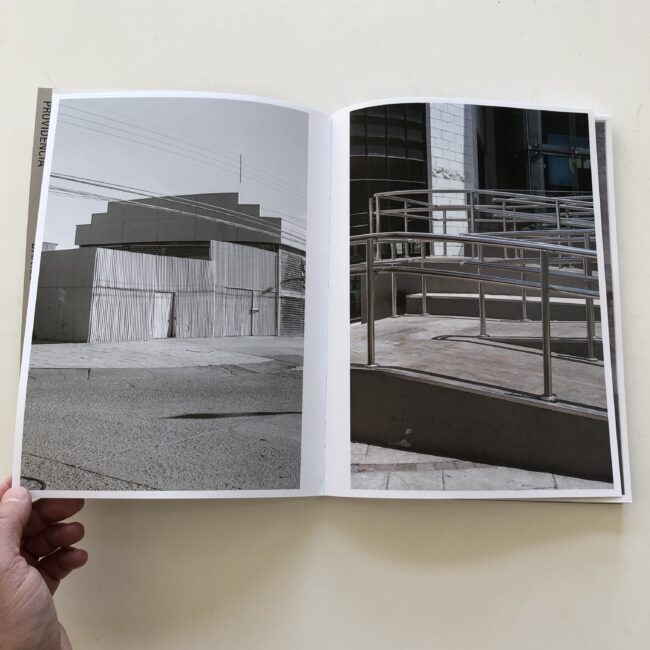

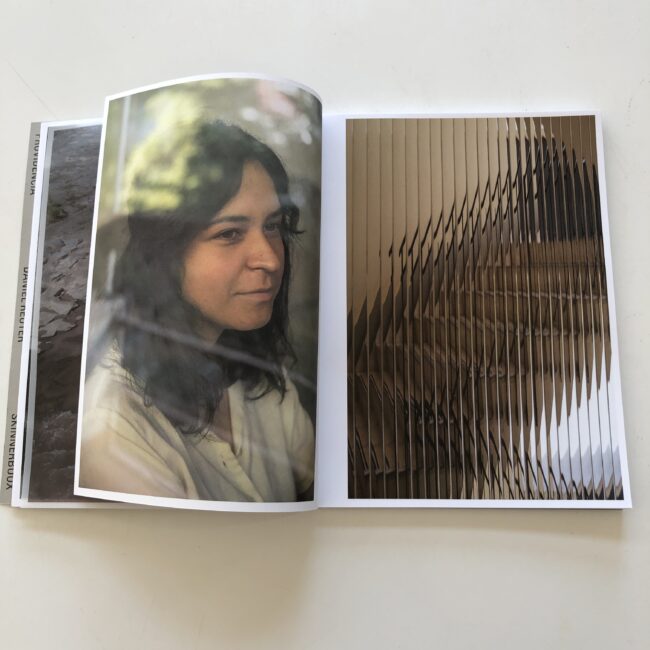

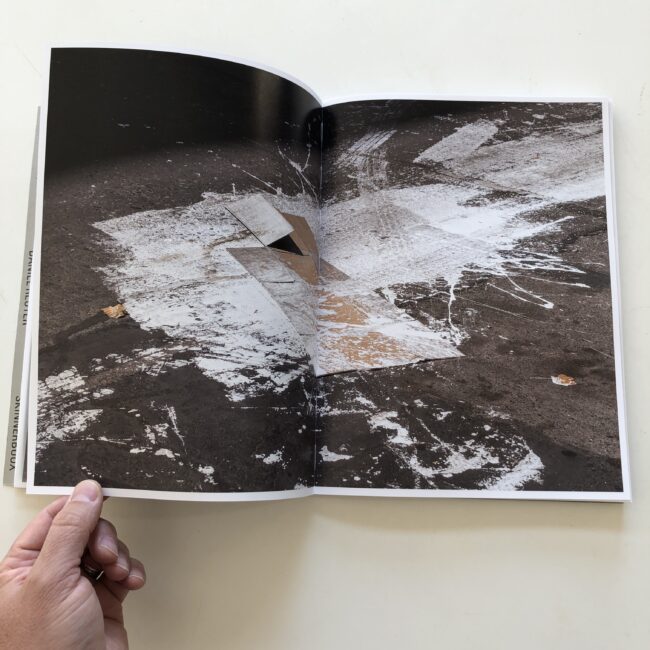

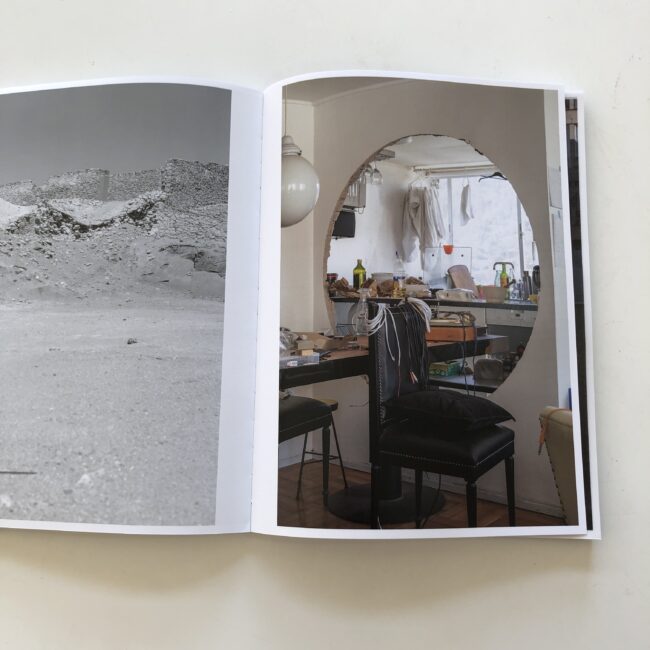

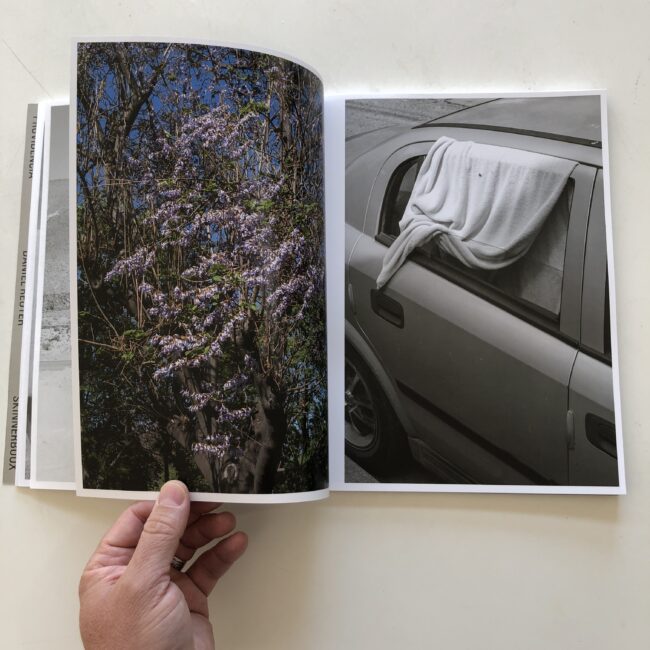

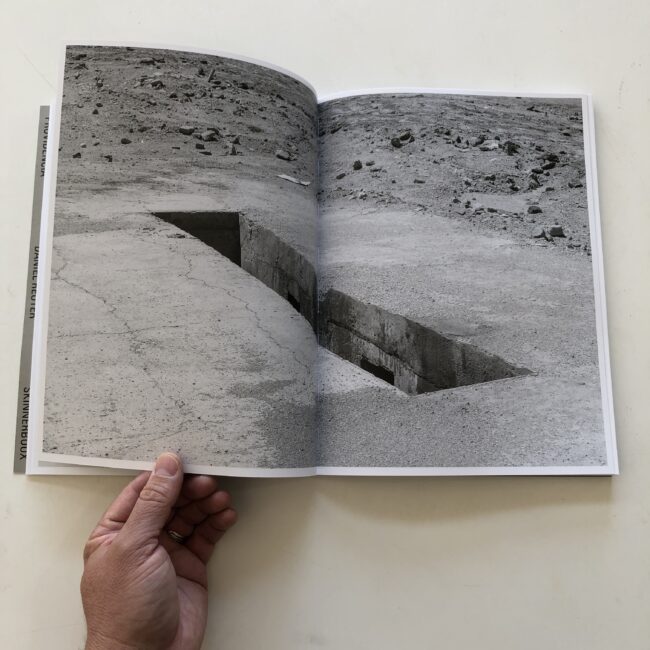

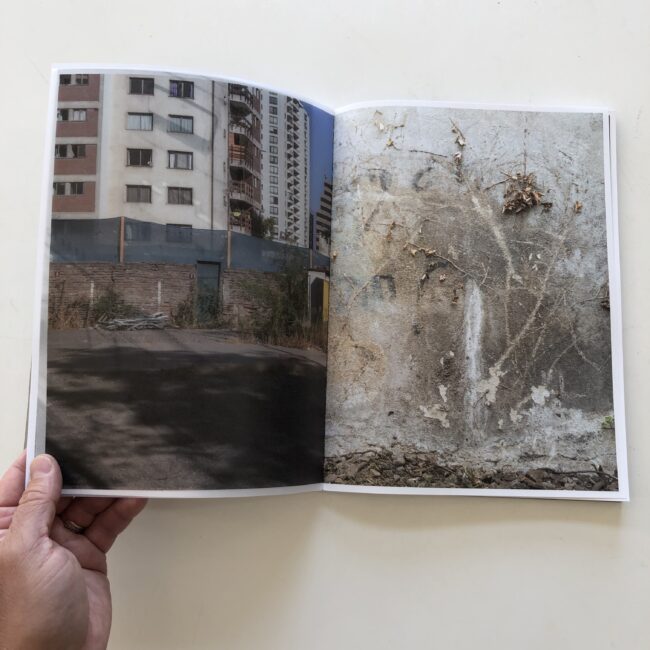

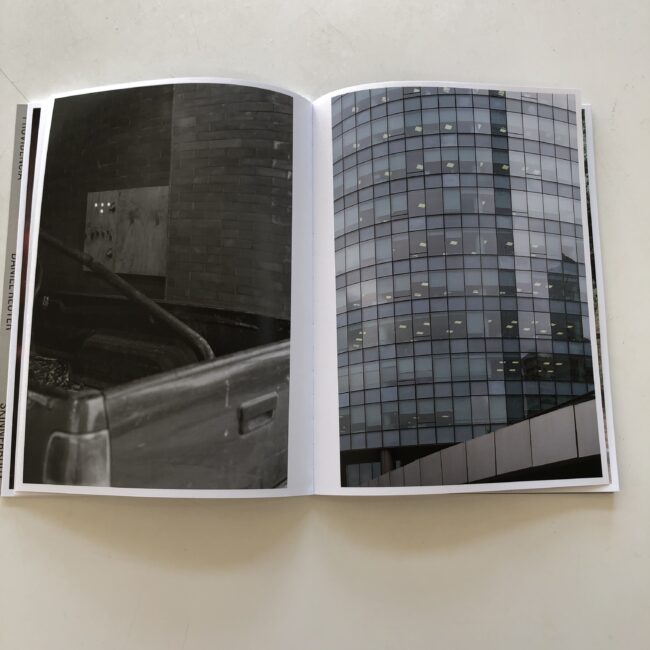

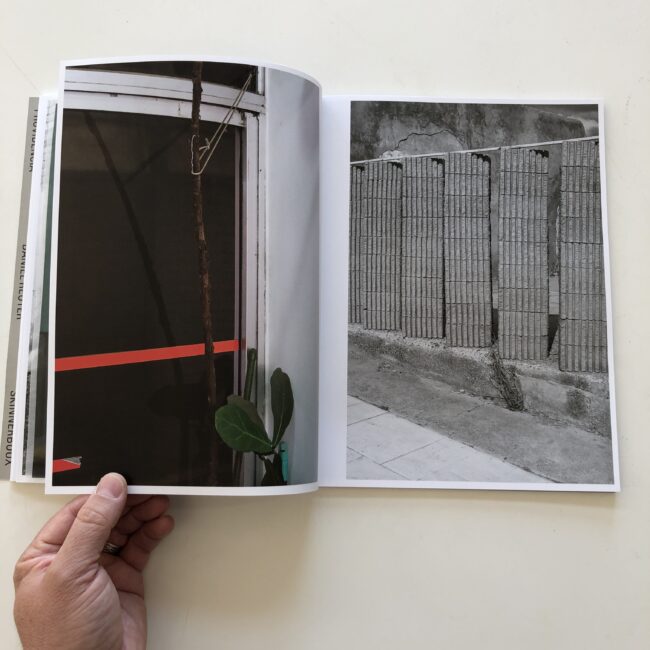

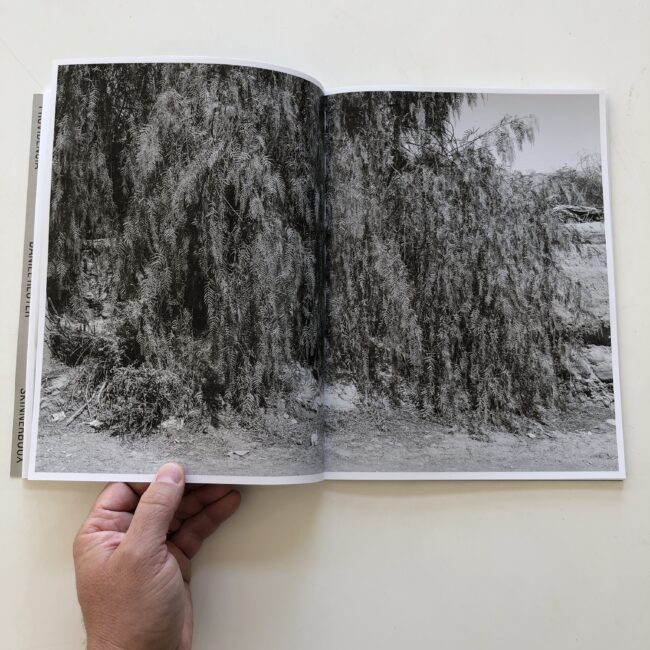

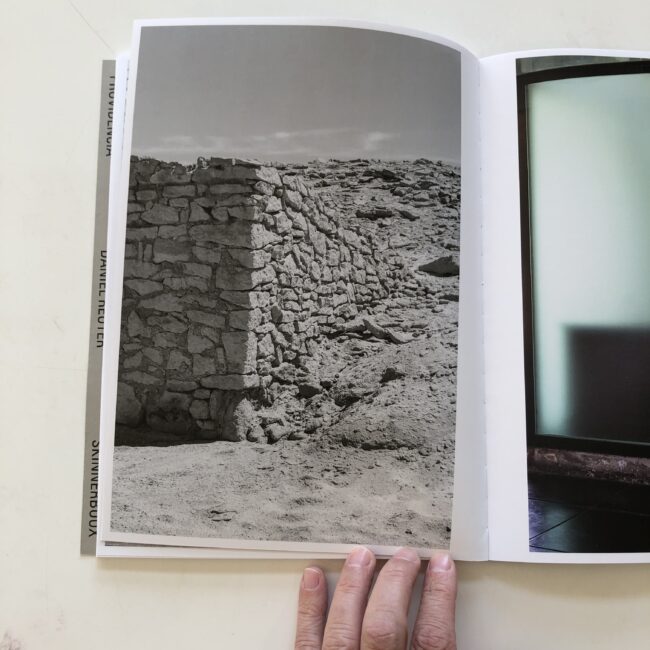

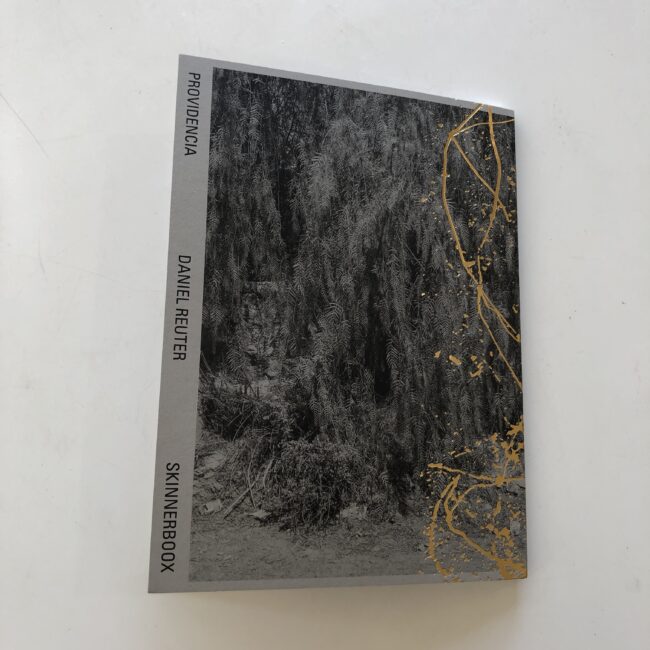

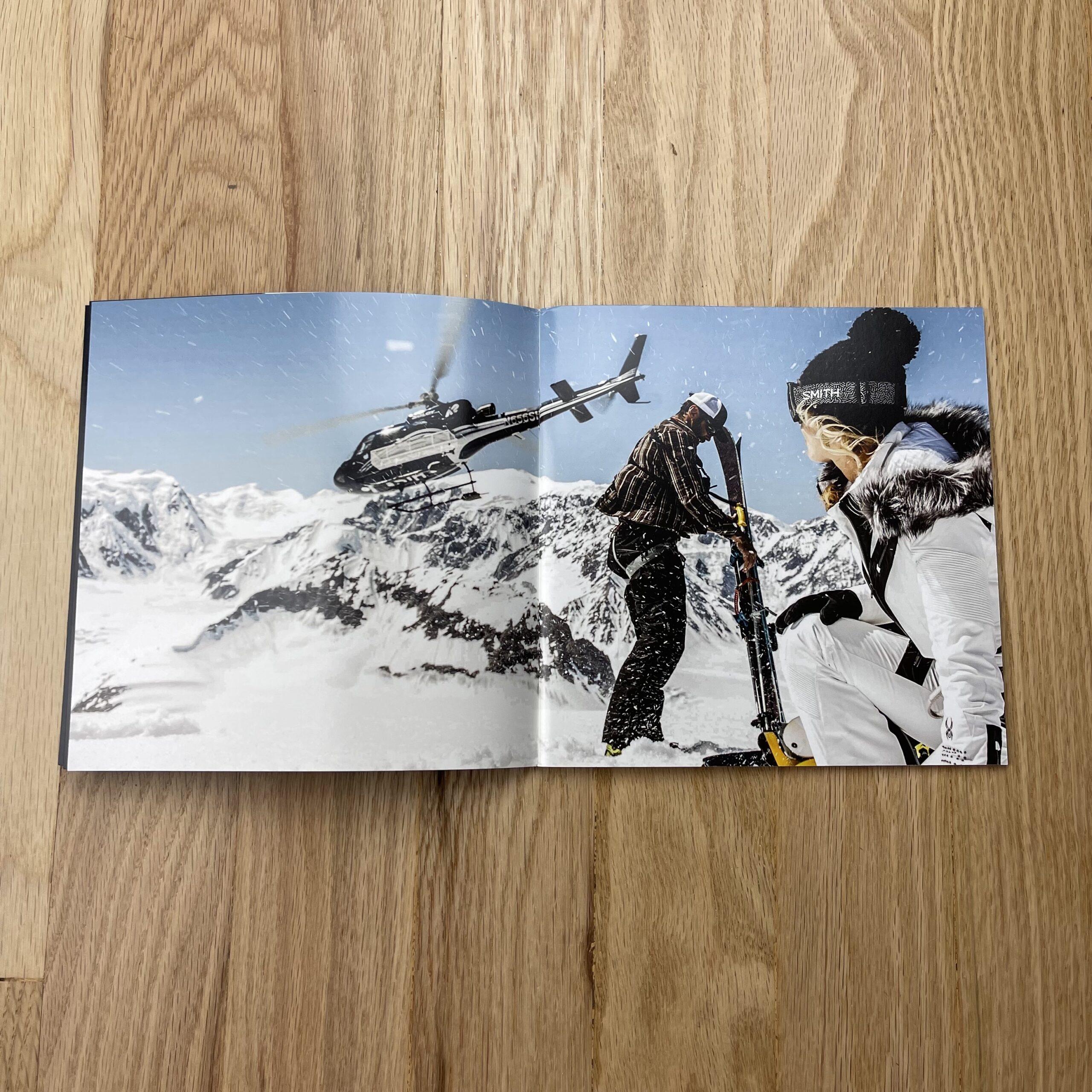

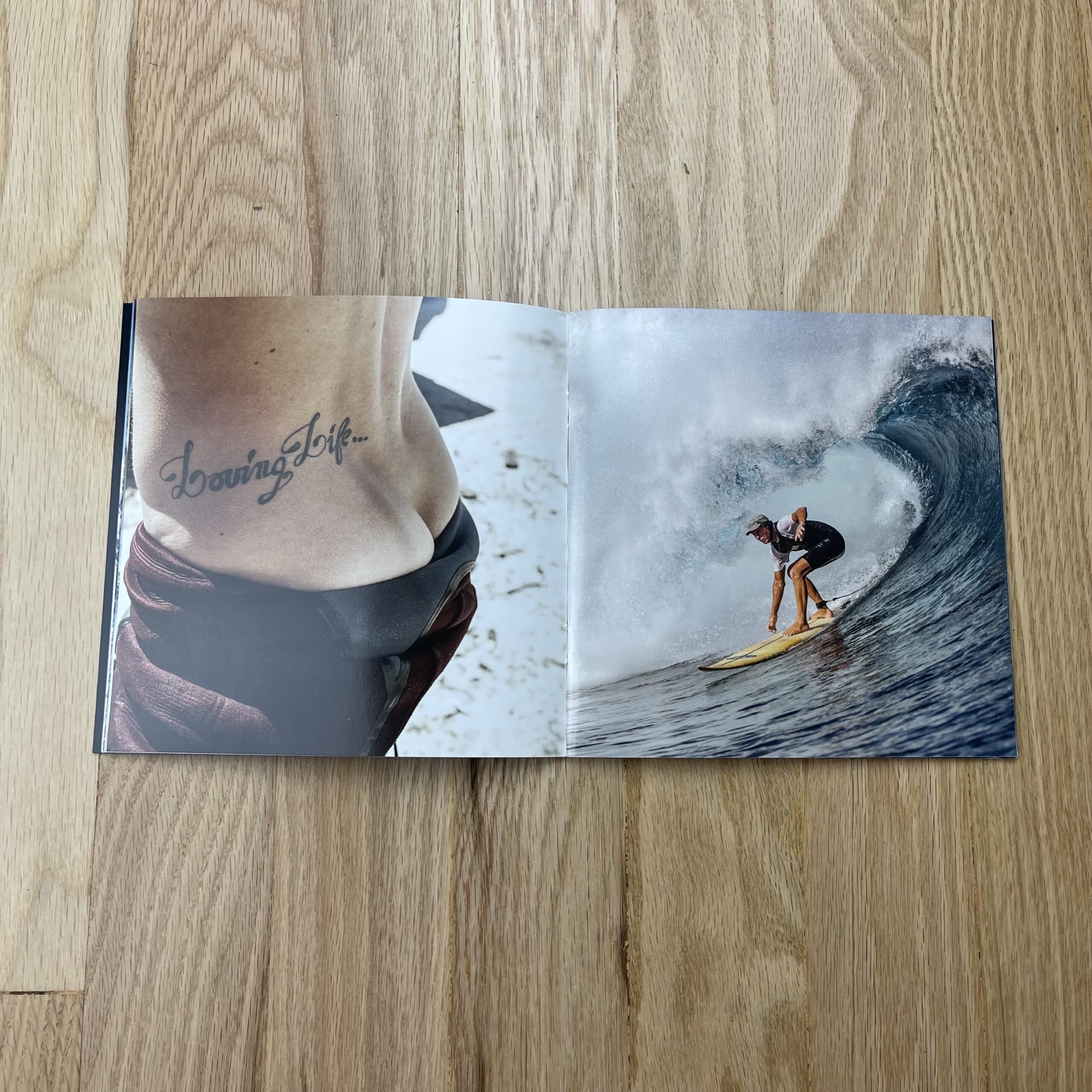

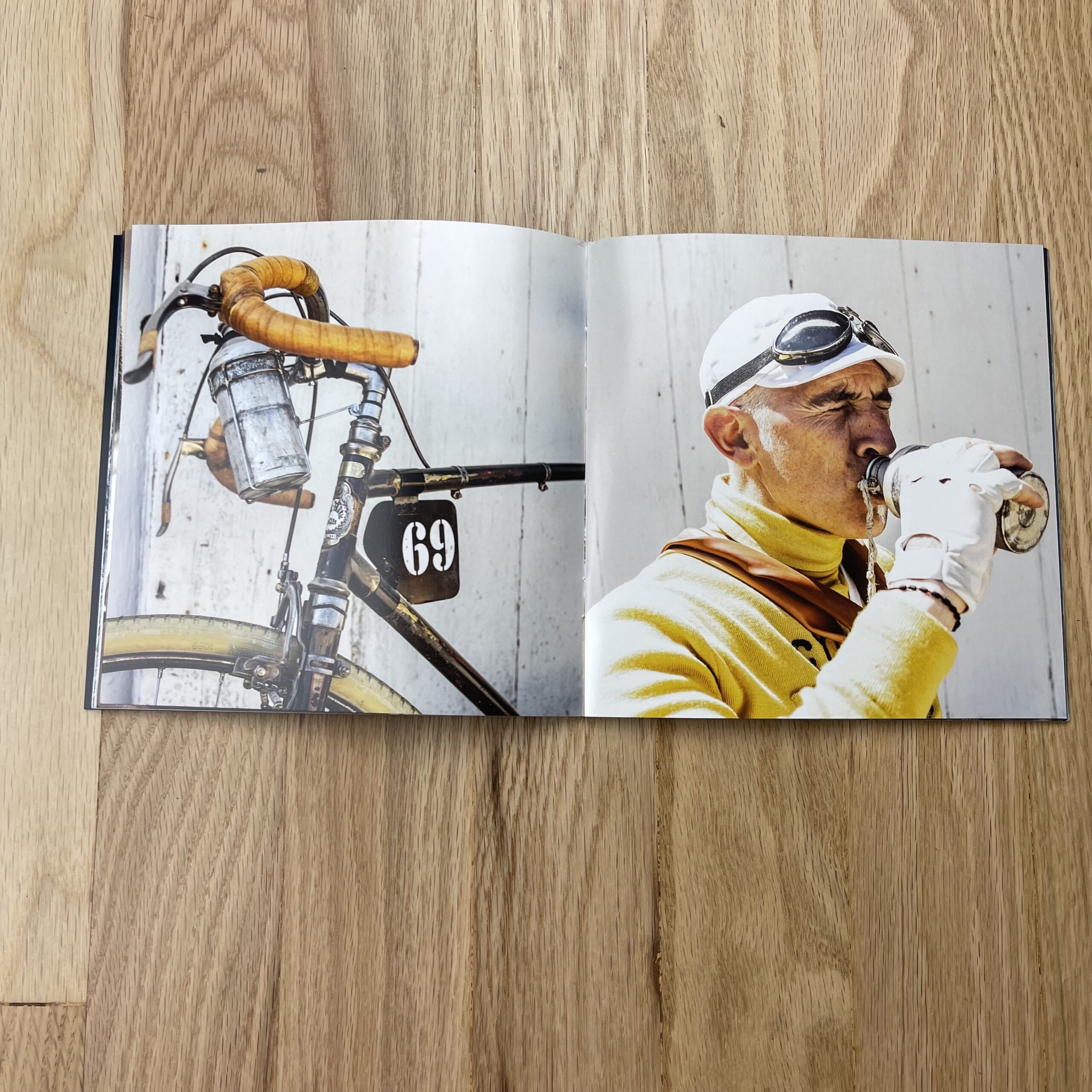

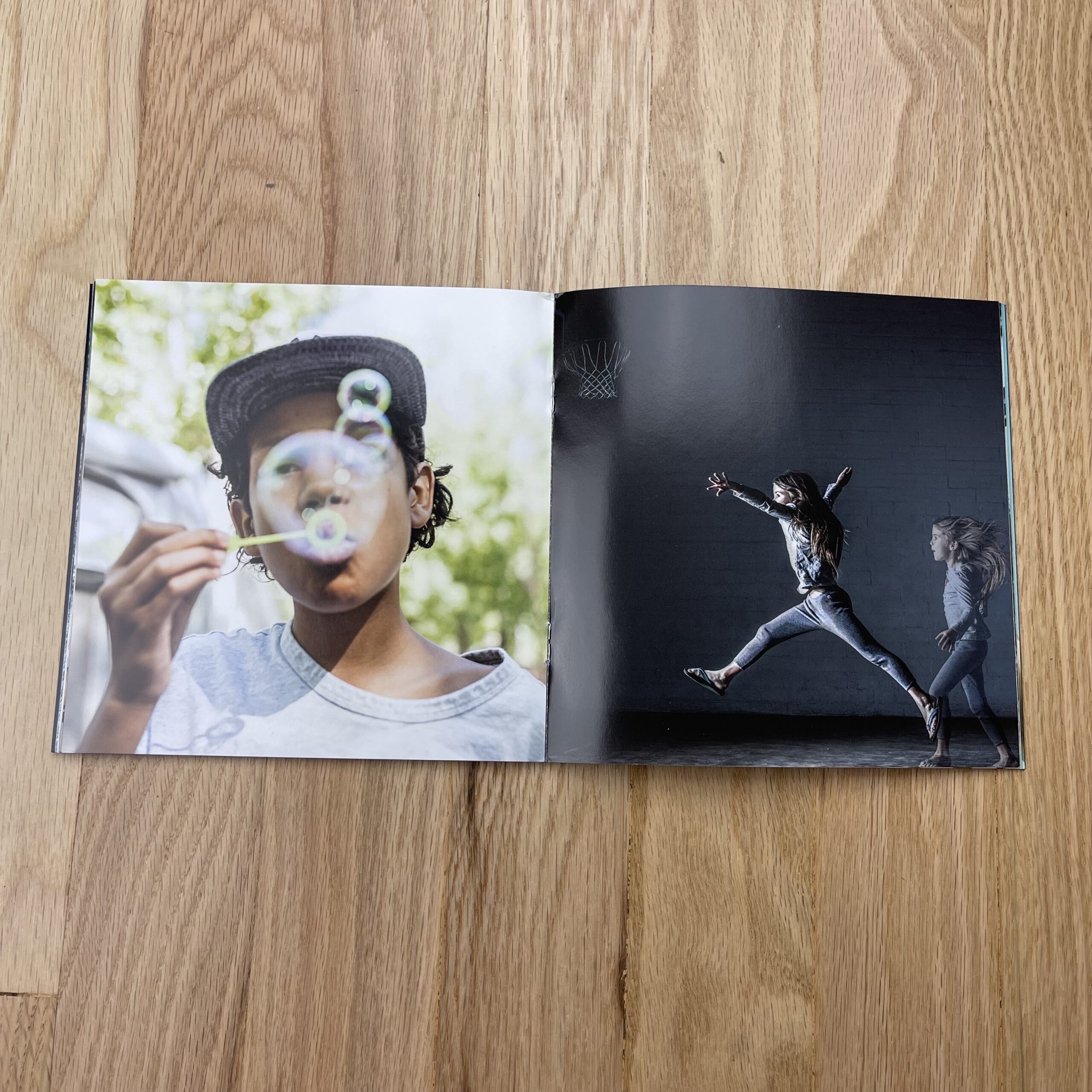

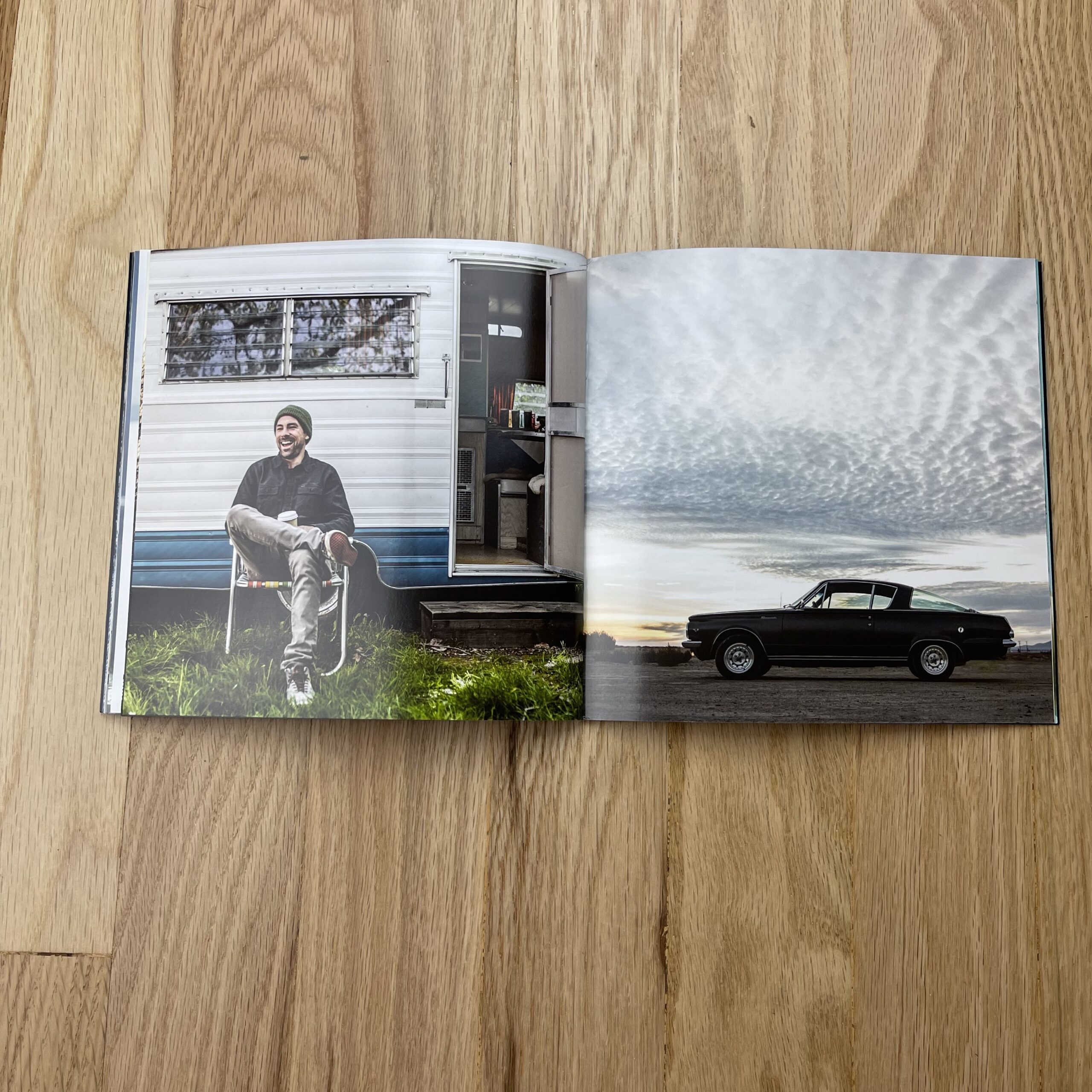

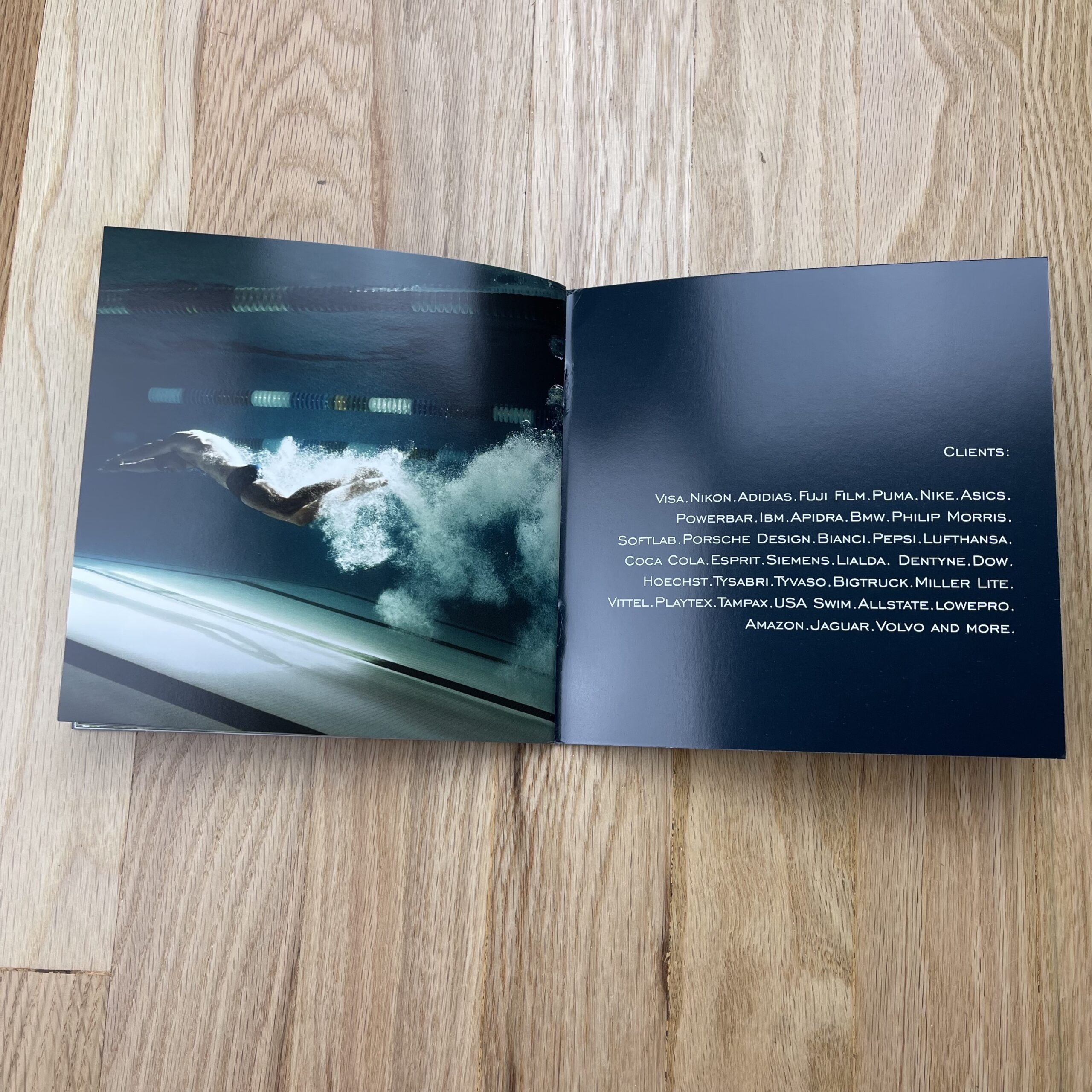

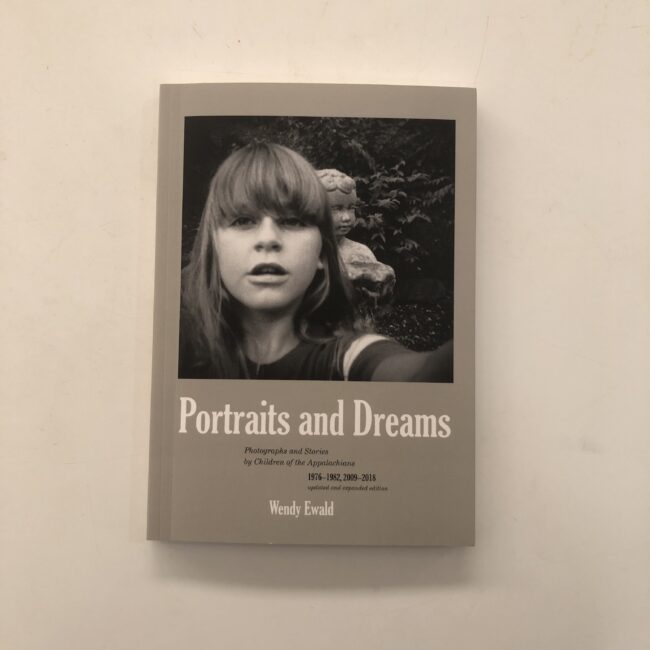

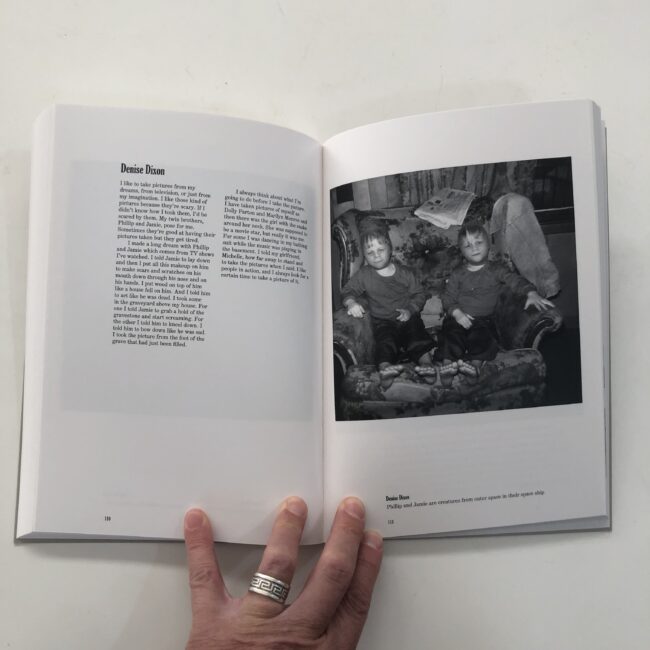

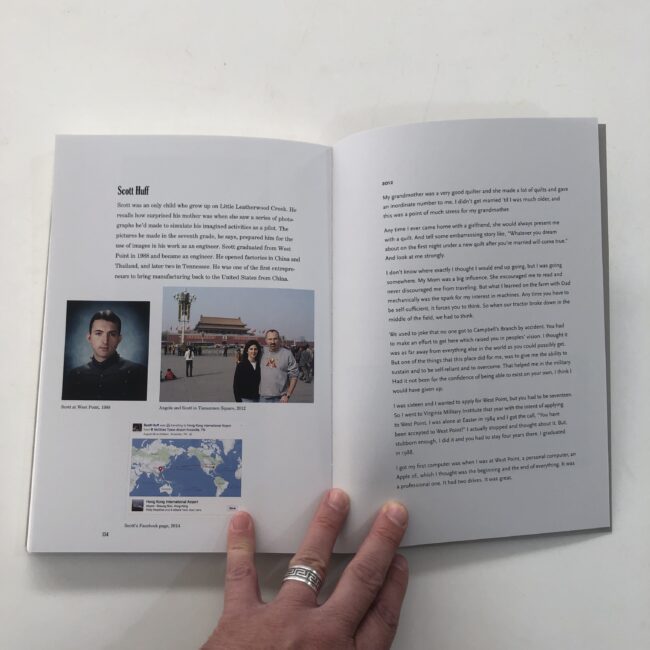

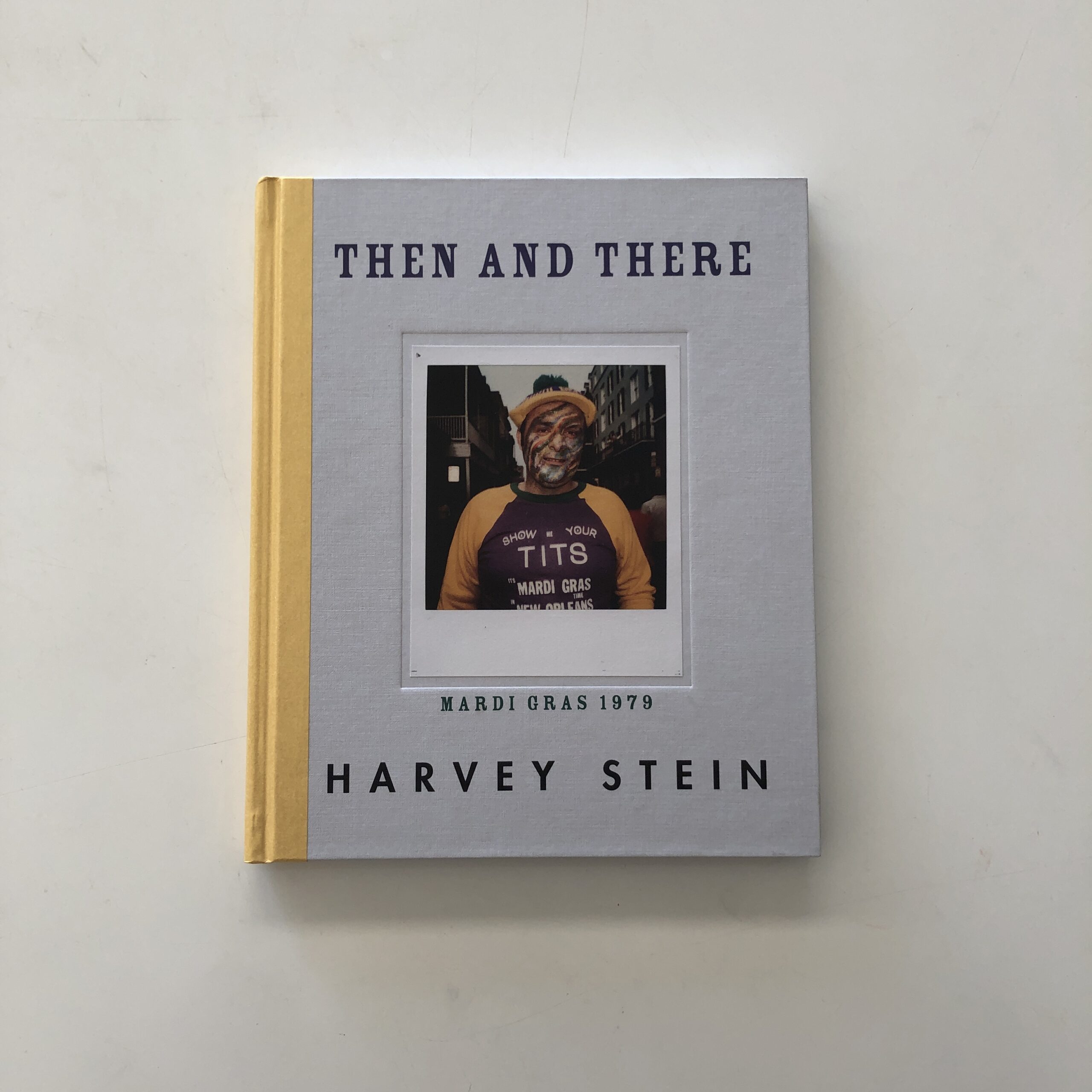

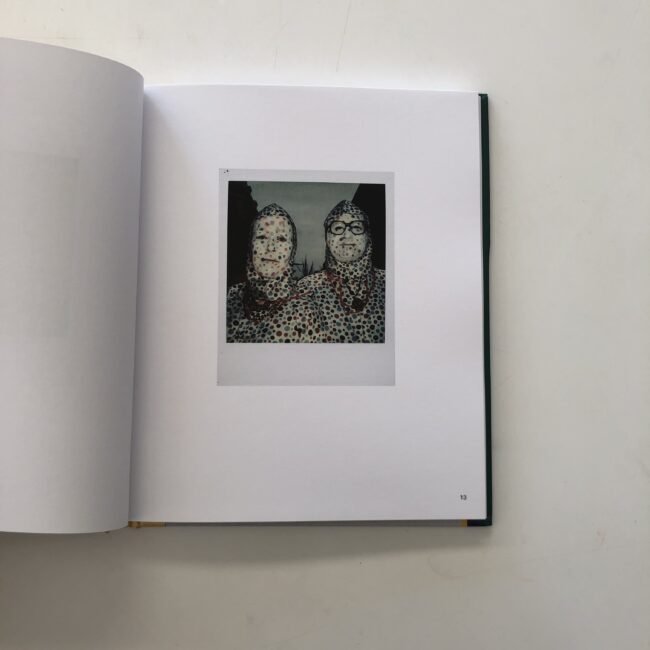

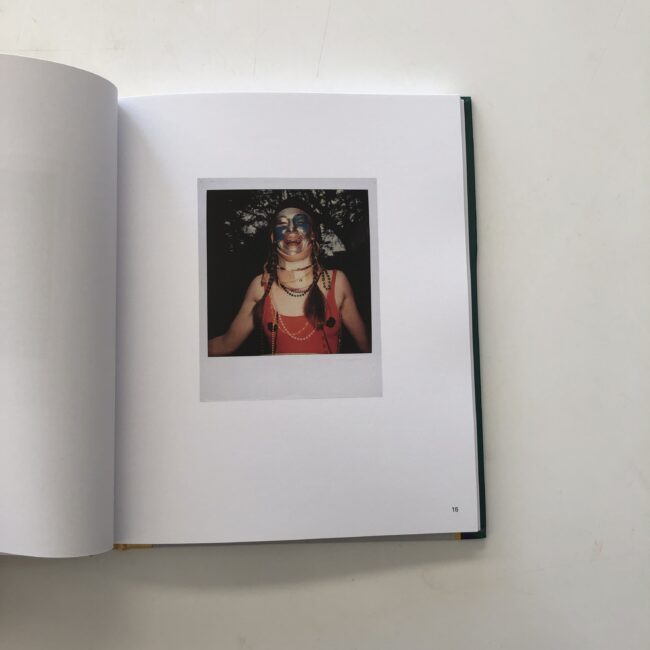

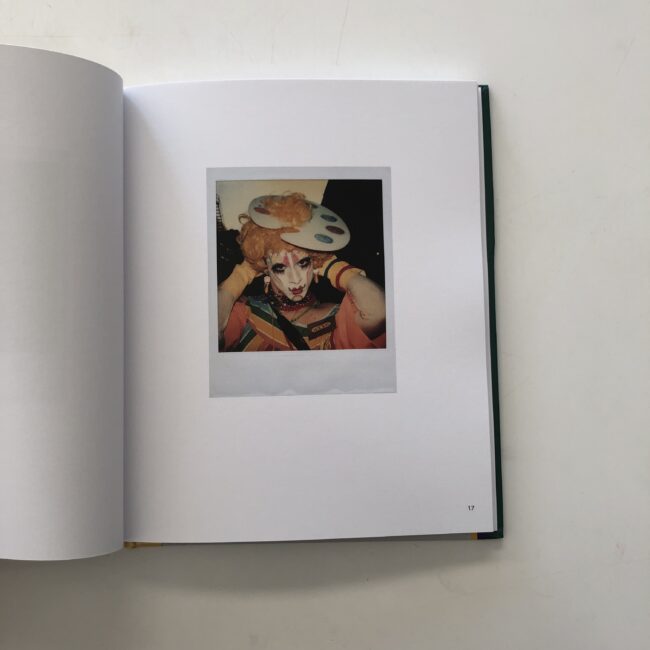

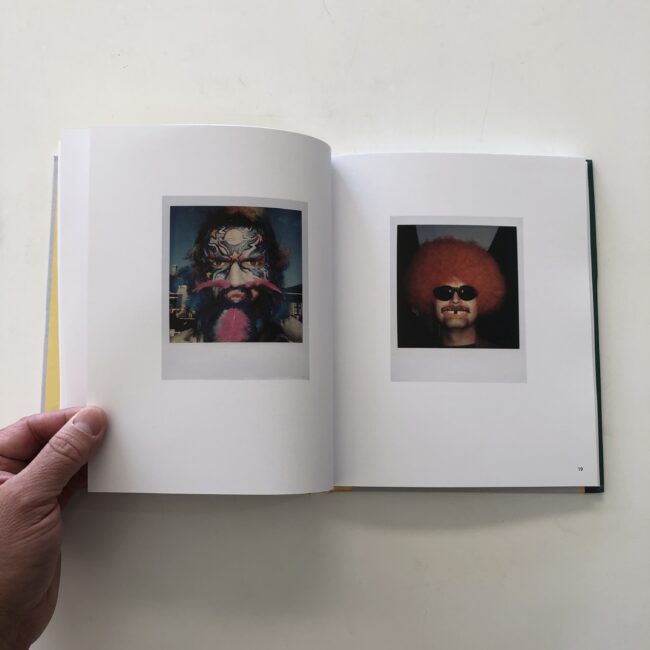

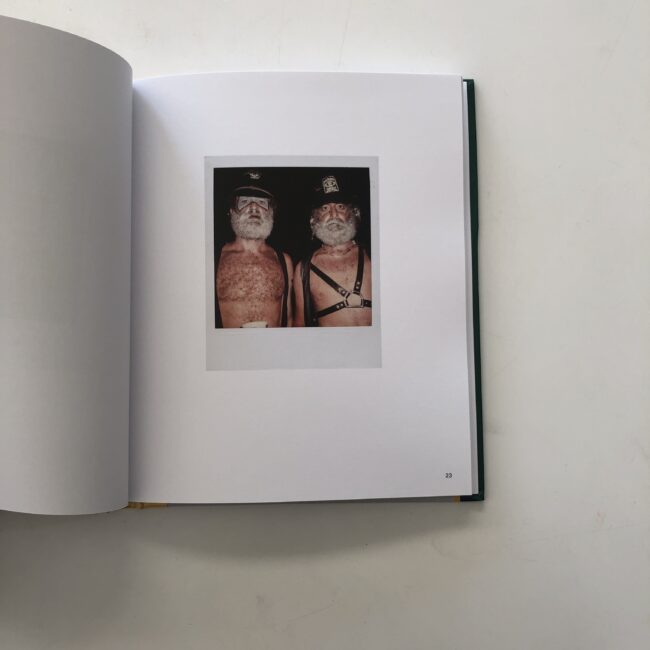

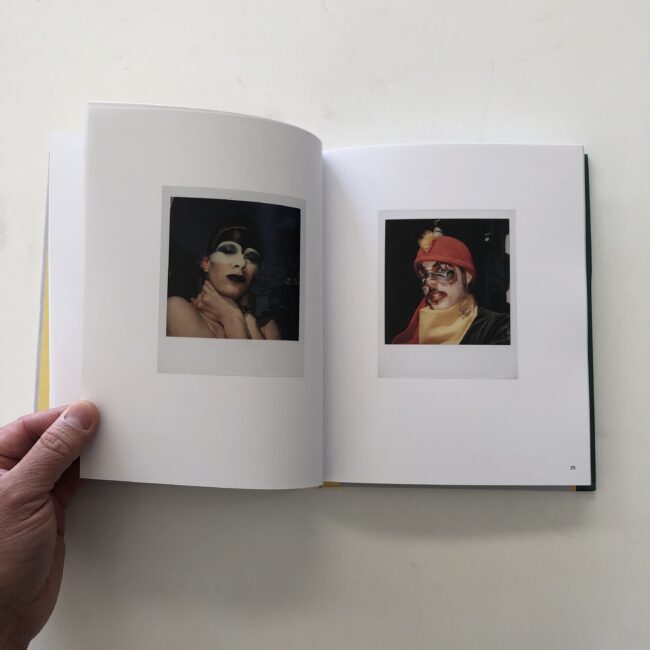

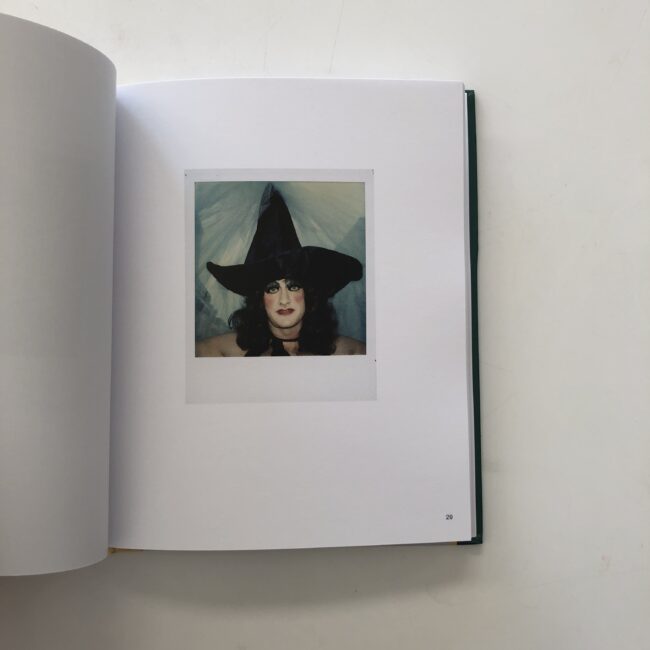

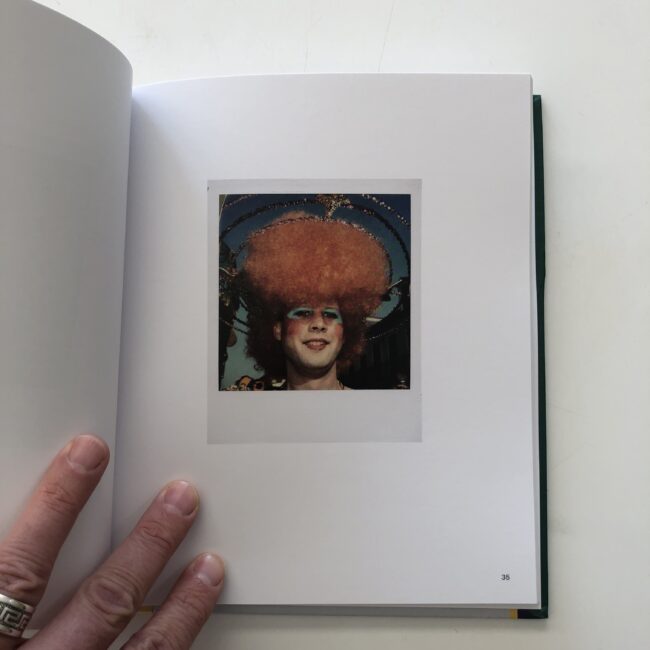

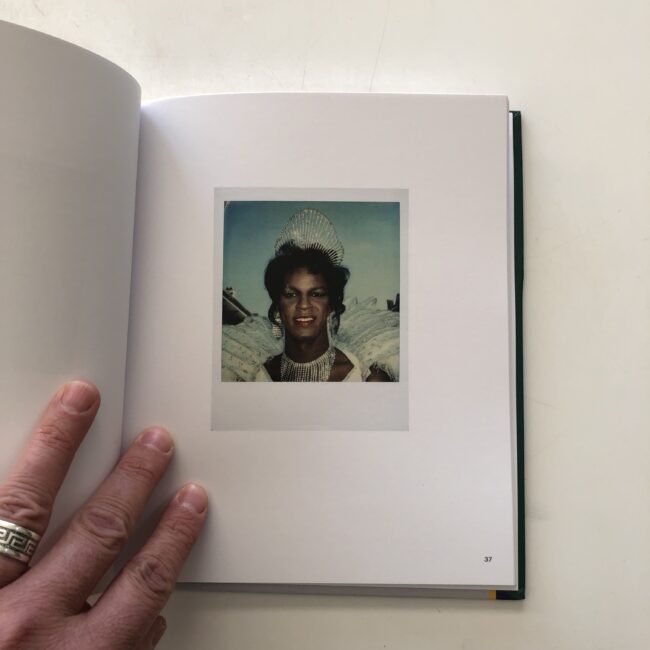

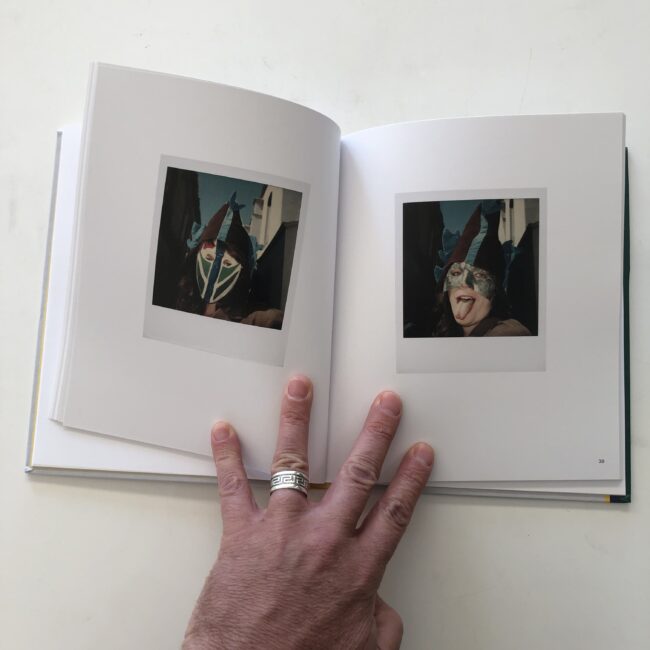

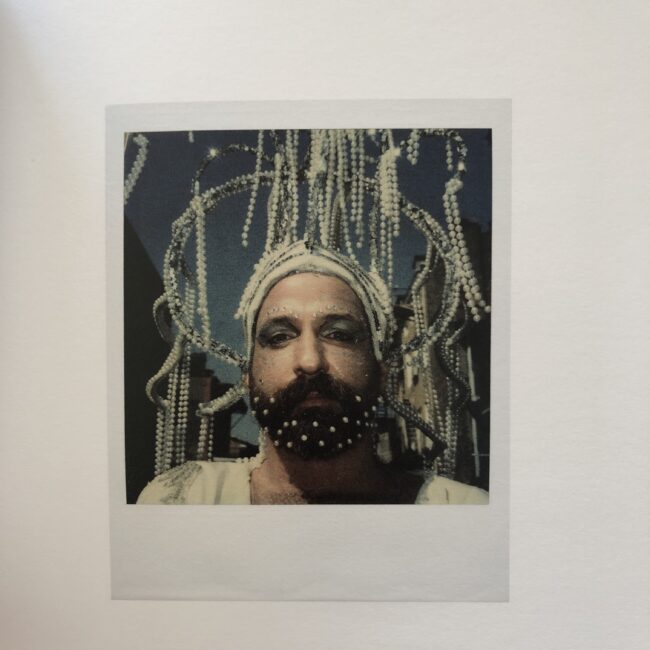

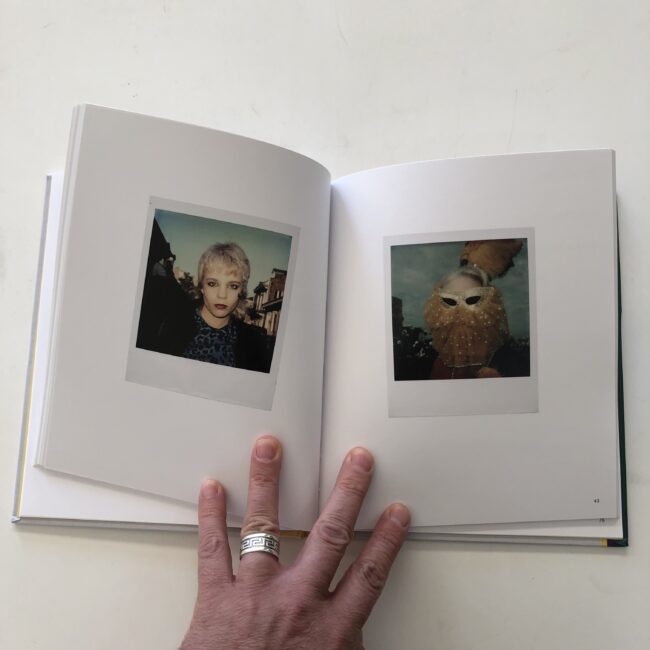

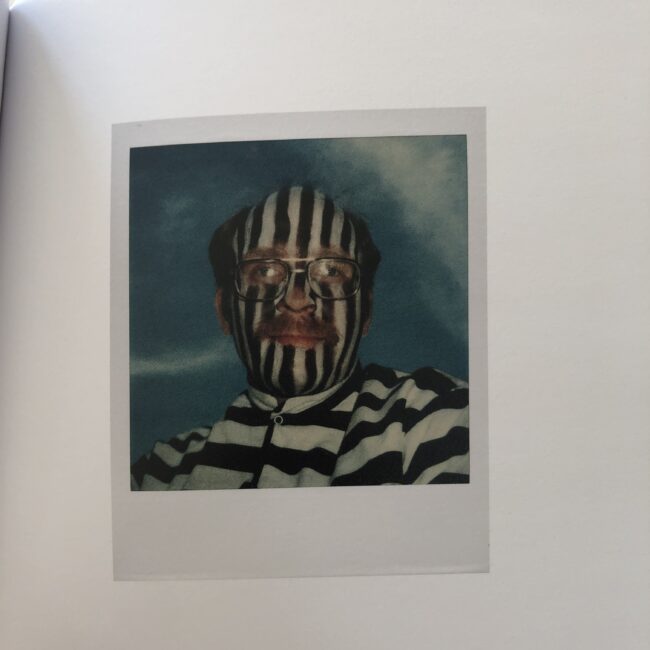

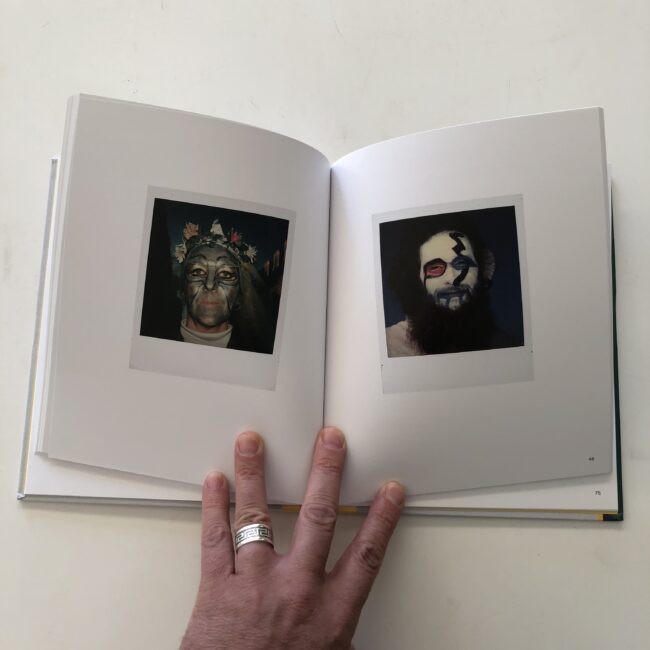

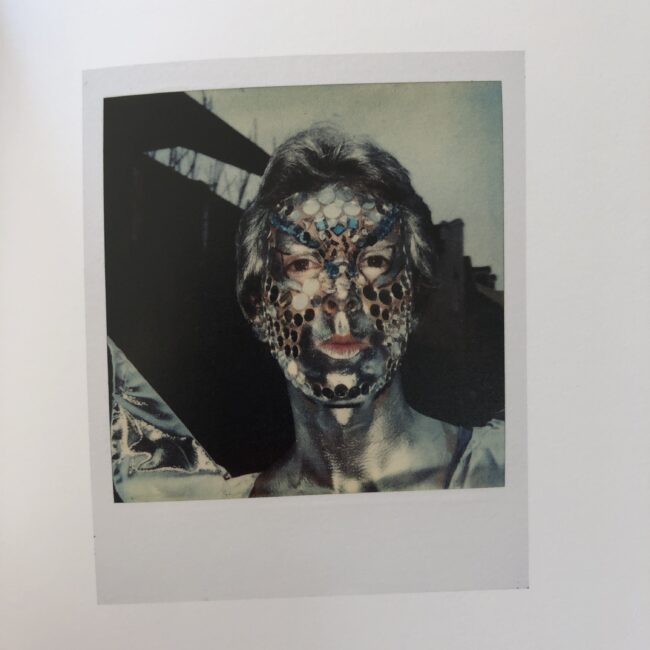

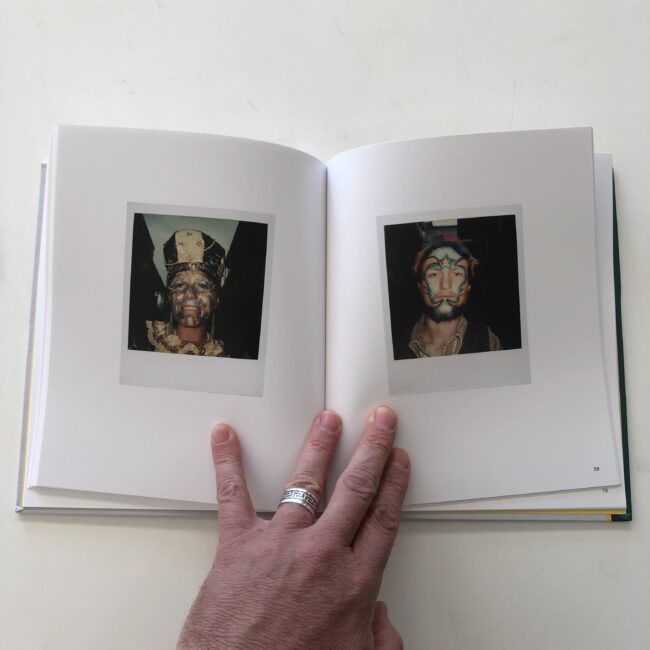

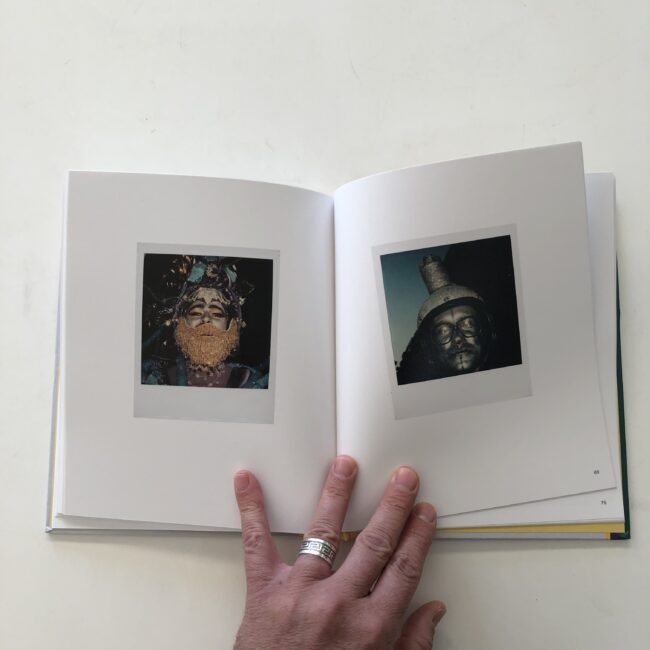

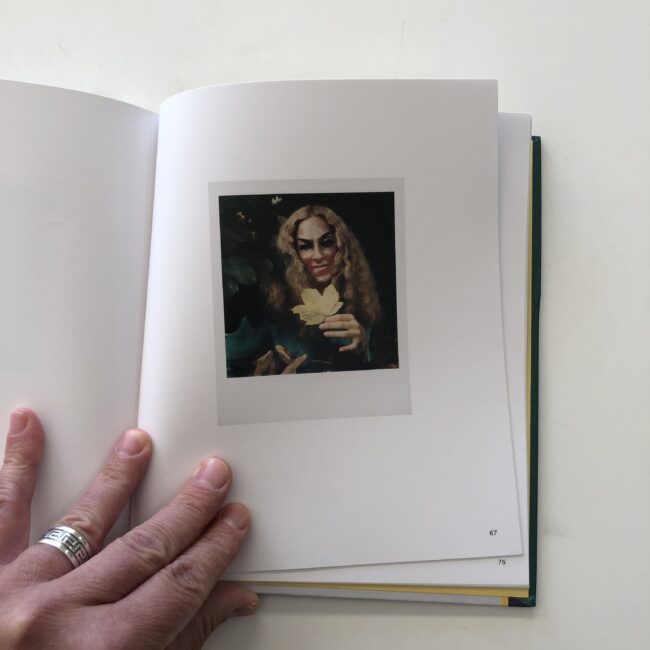

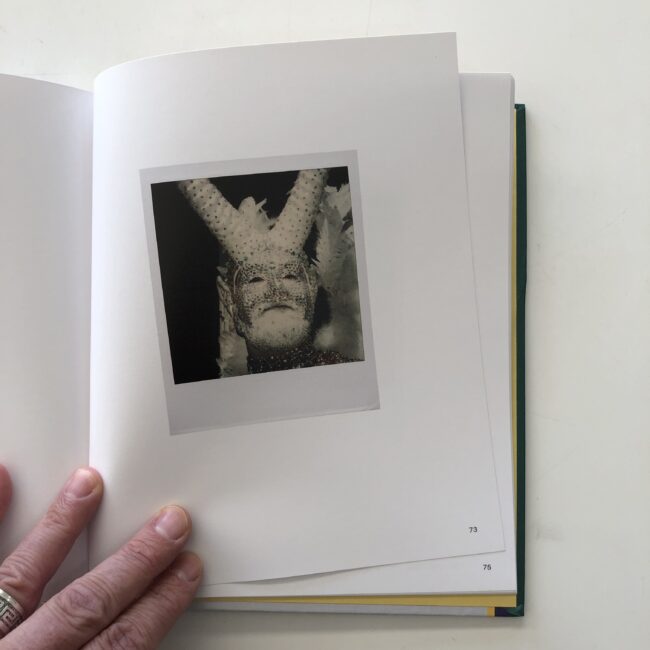

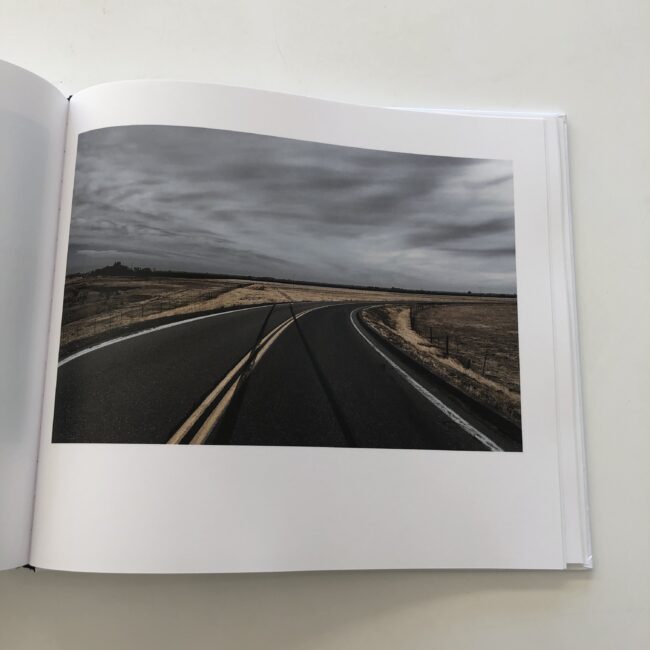

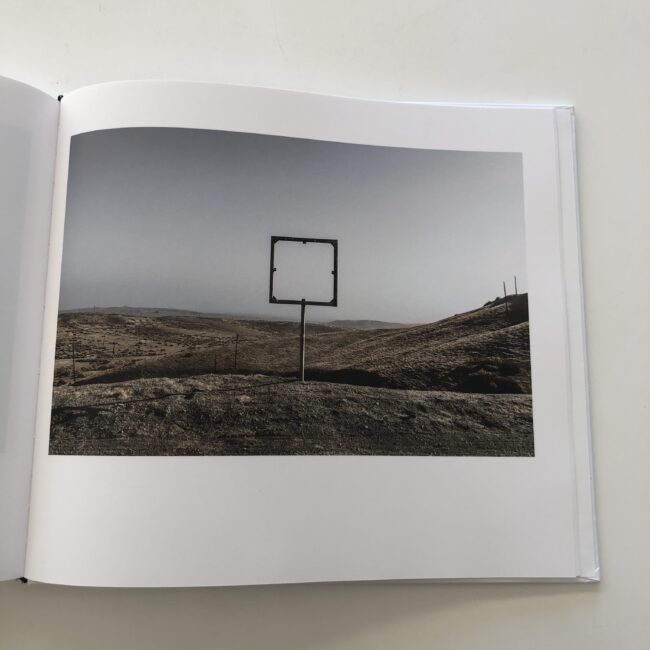

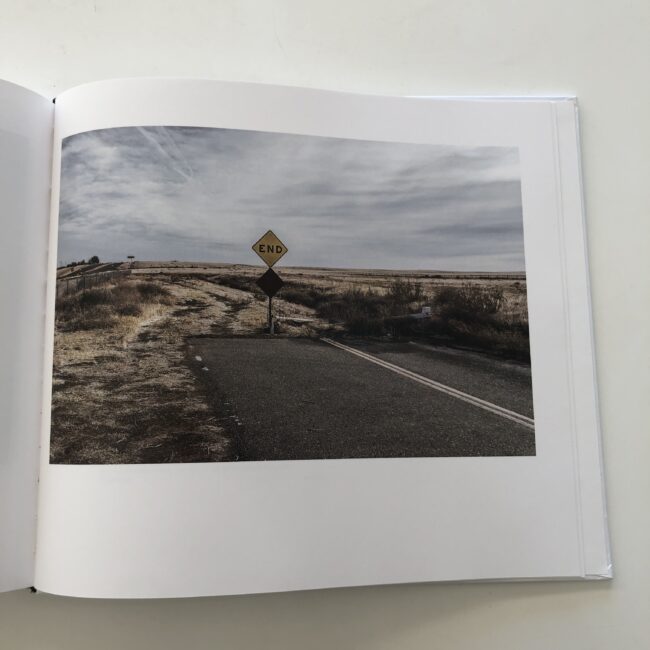

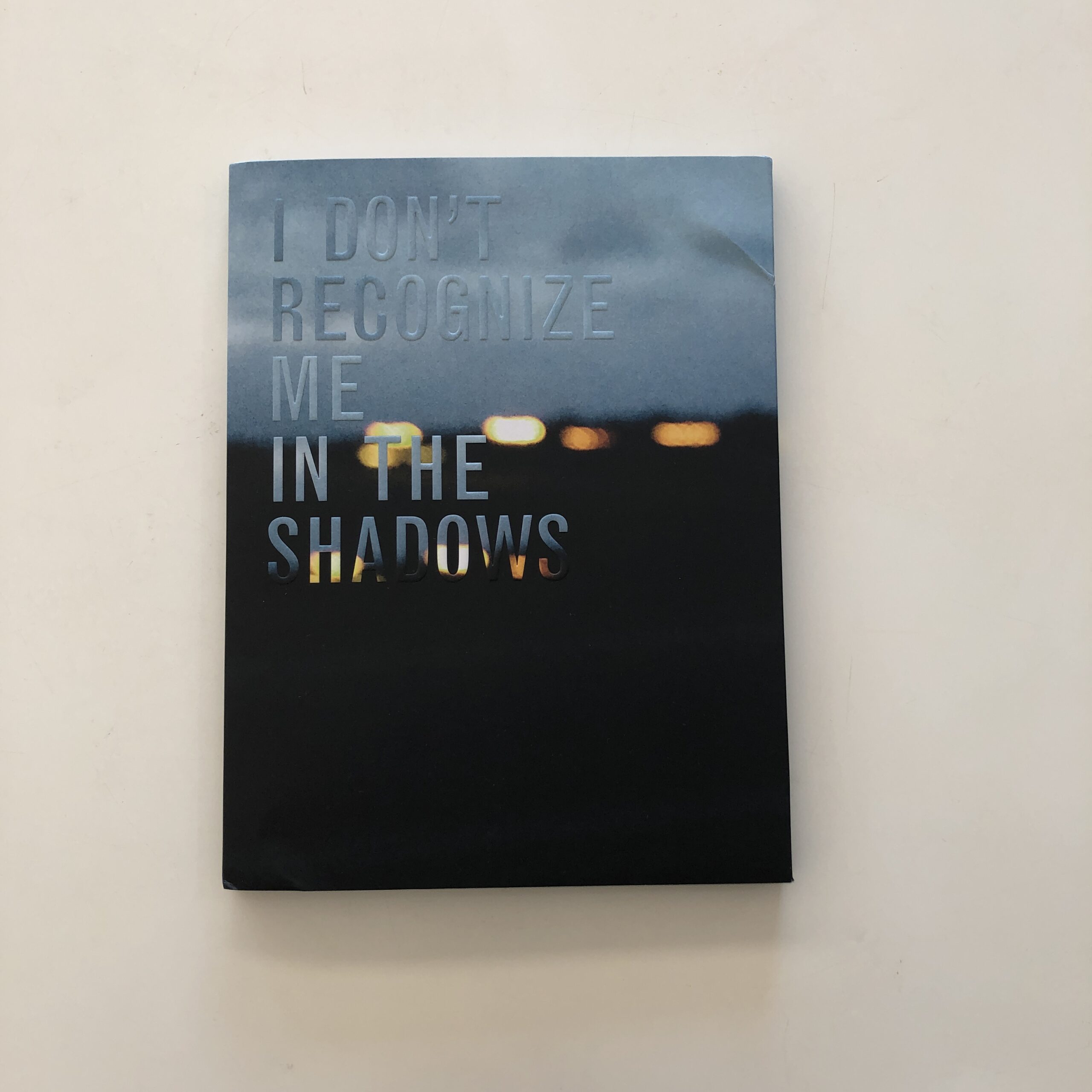

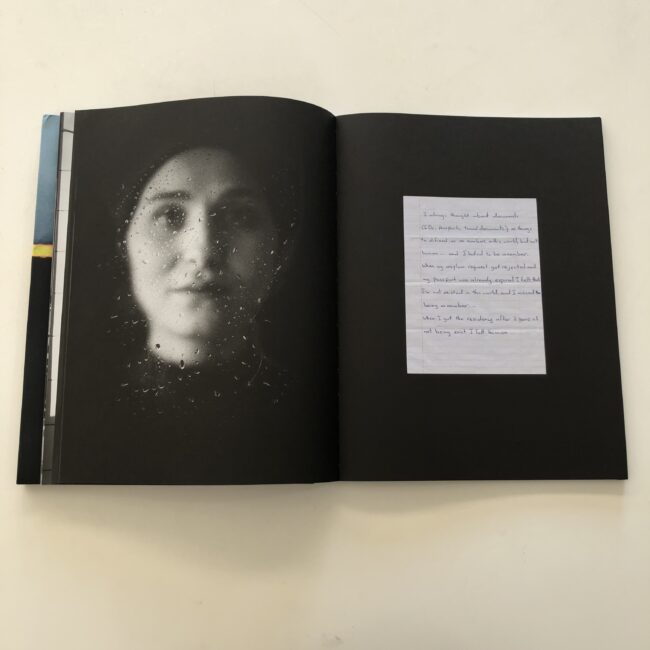

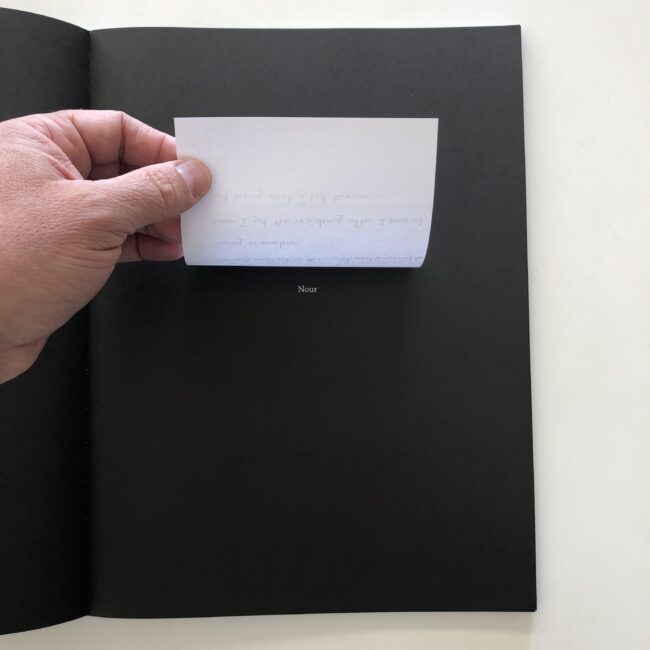

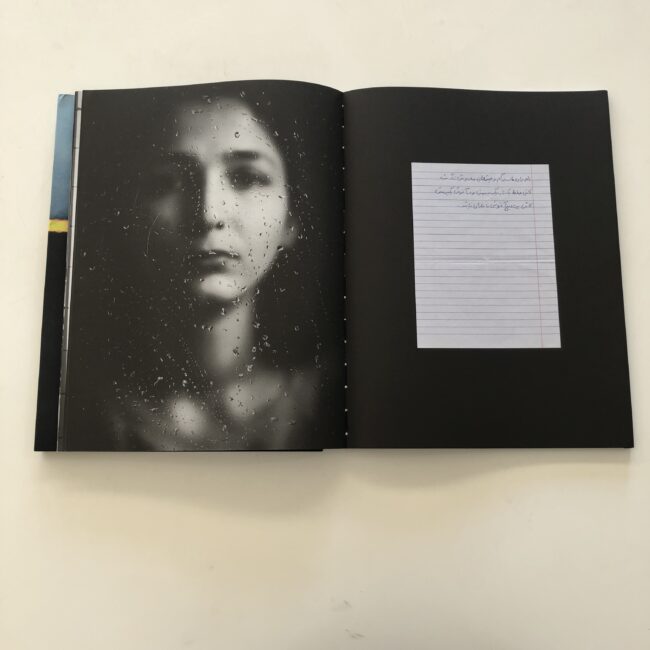

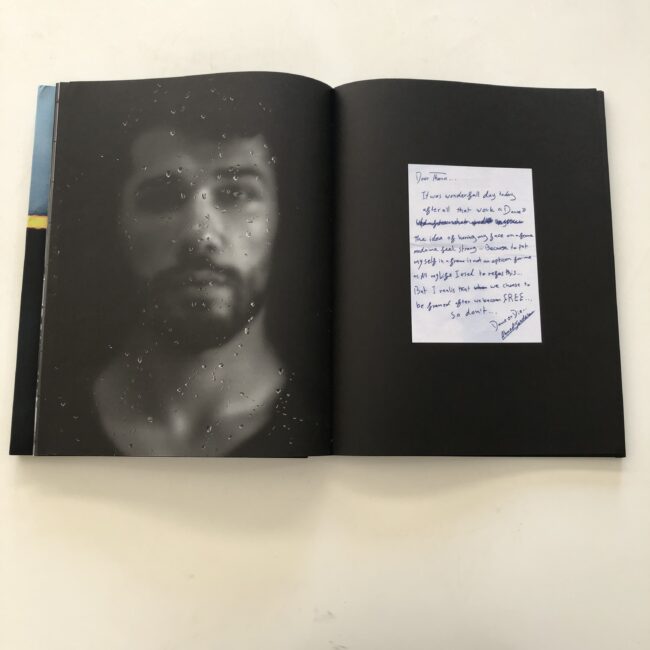

Today, I spent some time with “Providencia,” a book by Daniel Reuter, published by Skinnerboox, which arrived in the mail nearly a year ago. (Almost done with the 2020 submissions, thankfully.)

Today, as I sit here and write, I can honestly report that I was thinking of Andy Kaufman WHILE I was looking at the book, because I couldn’t make any sense of it at all.

Normally, when I spend time with a book, I look for clues, and figure things out, as slowly the narrative begins to focus. Eventually, I get there. (Almost always.)

But not today.

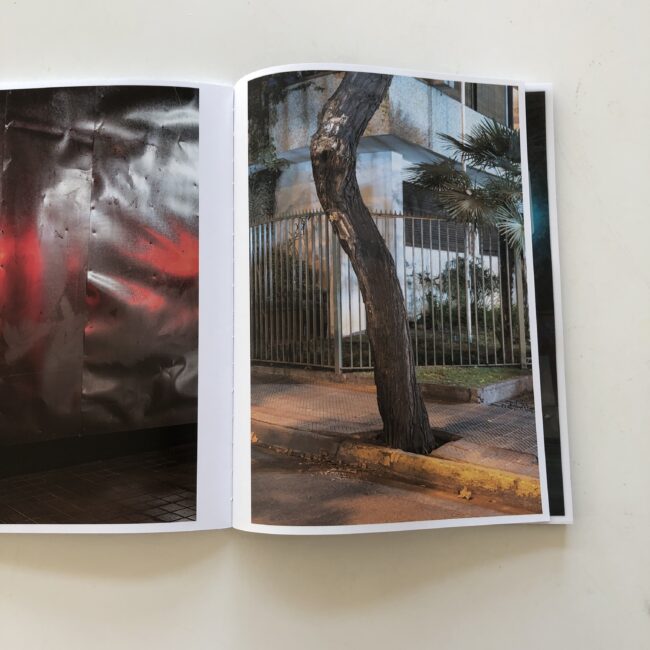

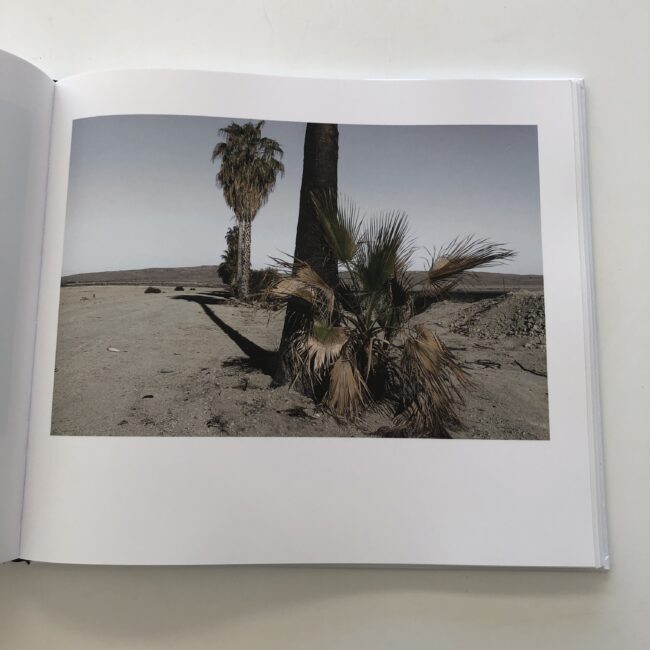

The title, which means Providence in Spanish, made me think maybe the series was made in Spain. (Such a Euro-centric vision of the world, it’s true.) And early on, there is a publication in Spanish, so that exacerbated my reaction. (As did the inclusion of a palm tree in one photo.)

But as to the theme, or point of the work?

I just couldn’t get there.

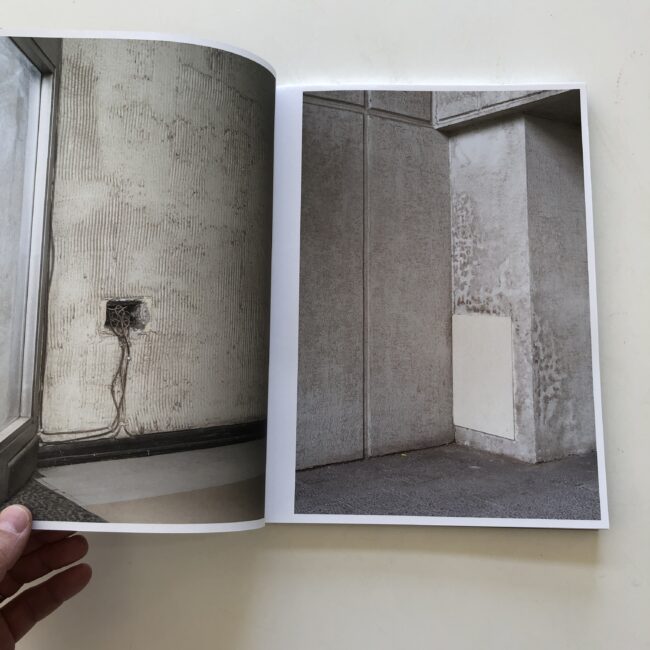

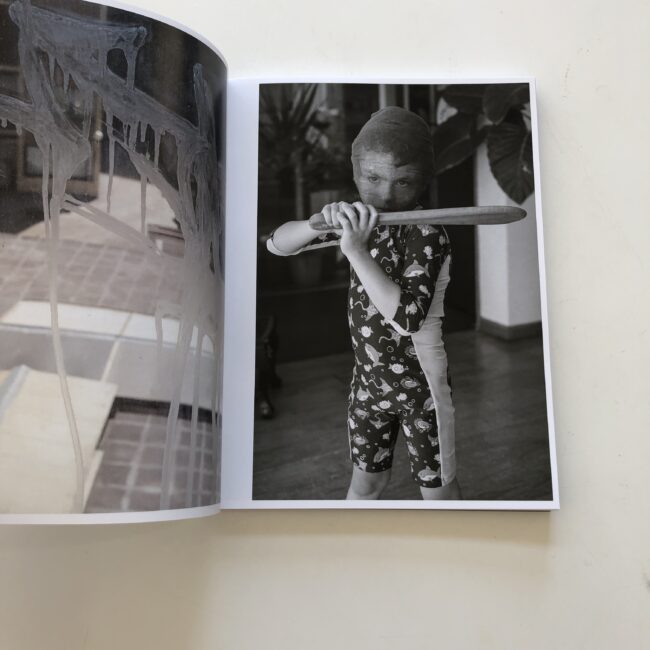

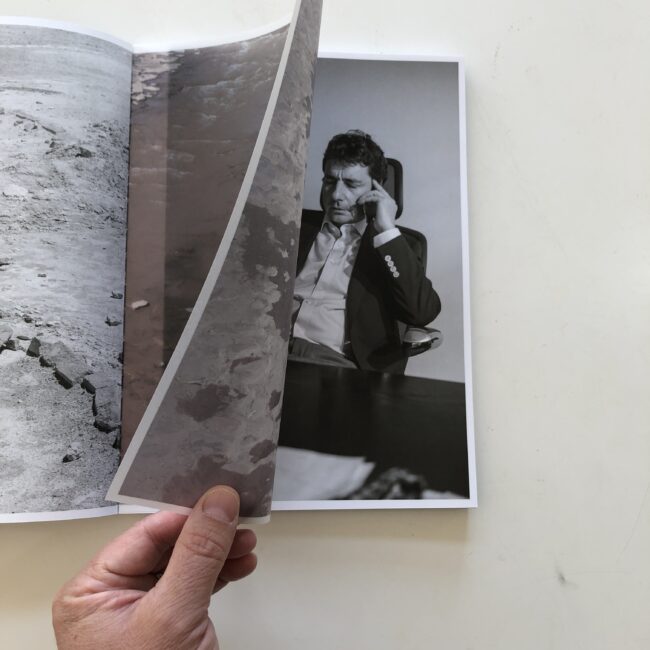

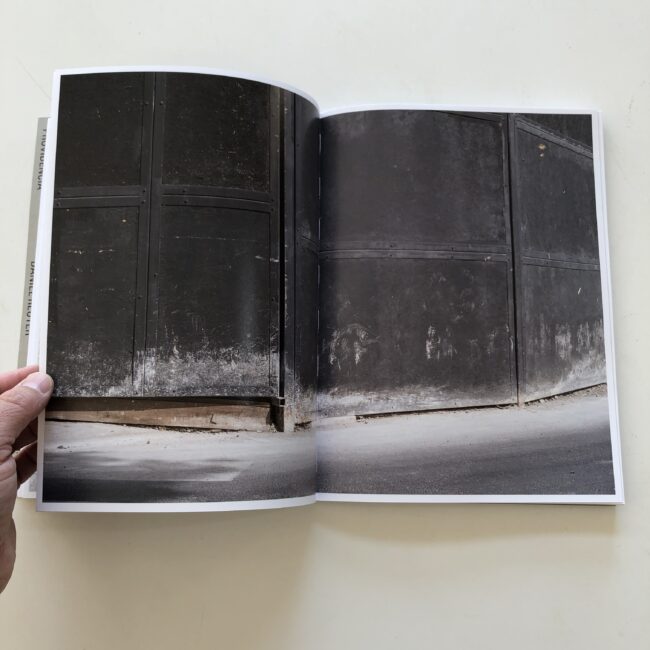

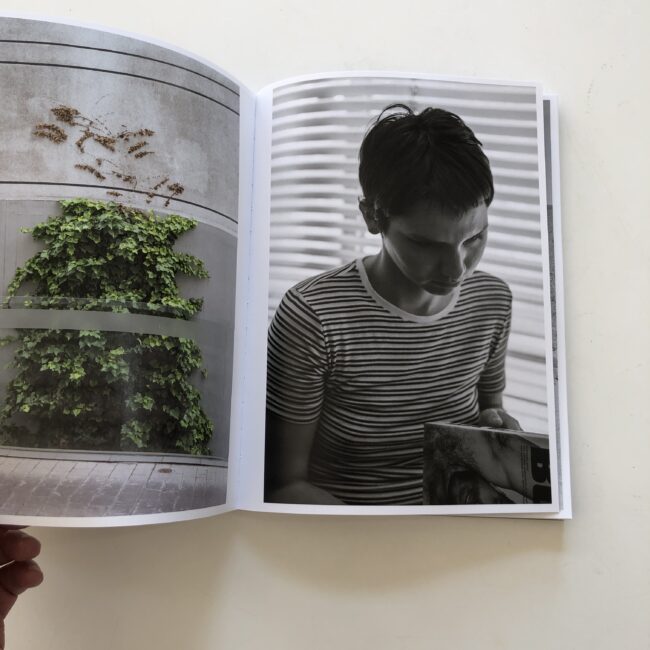

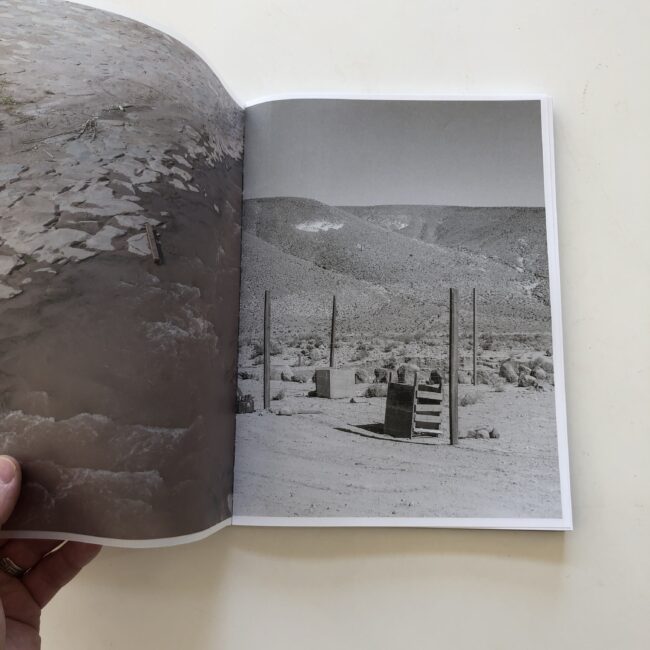

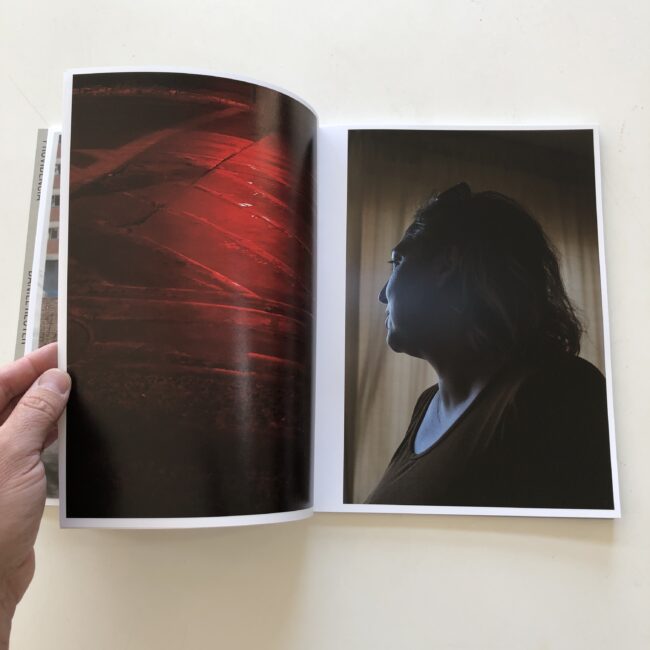

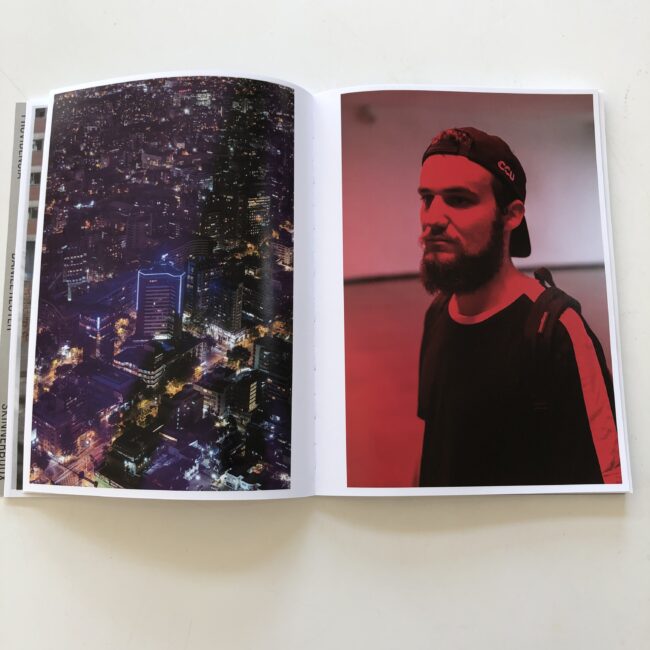

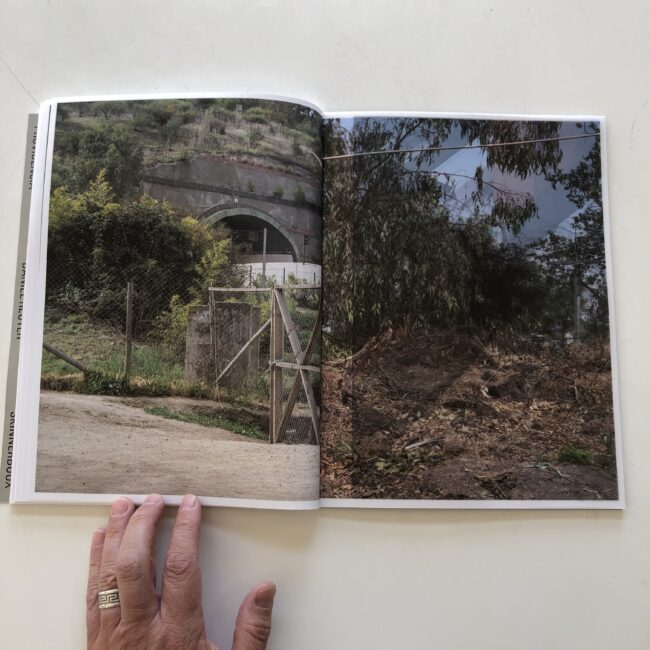

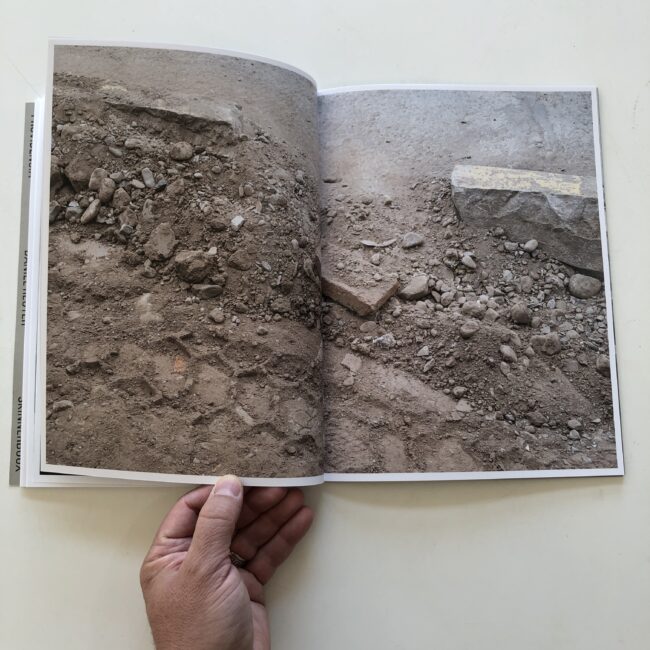

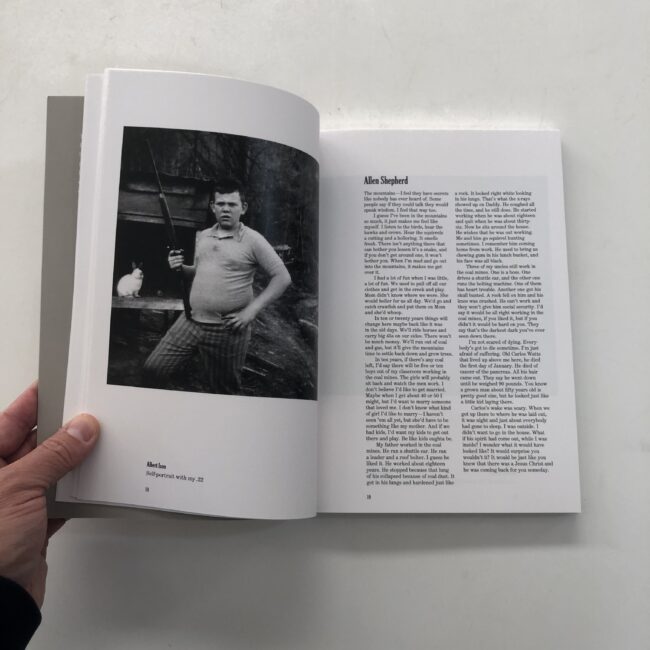

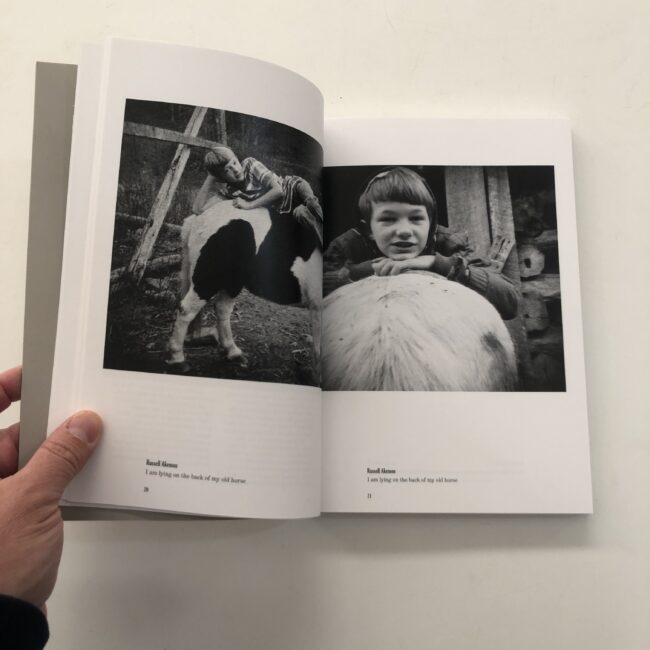

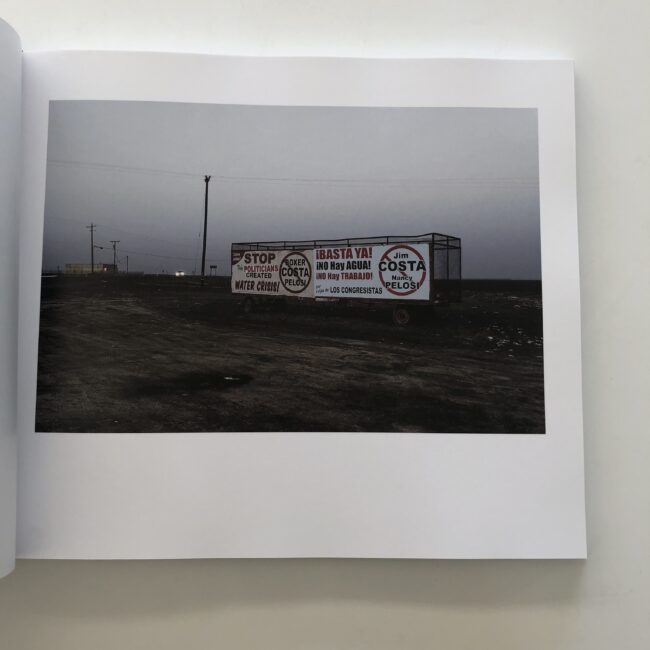

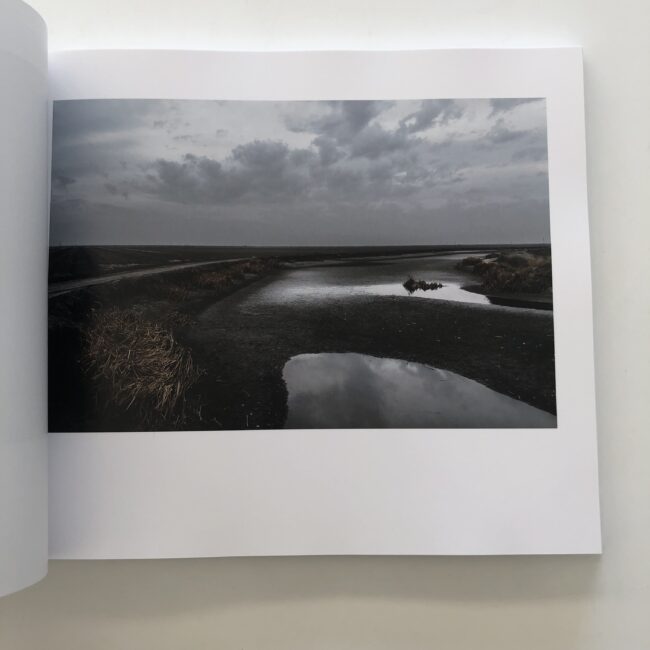

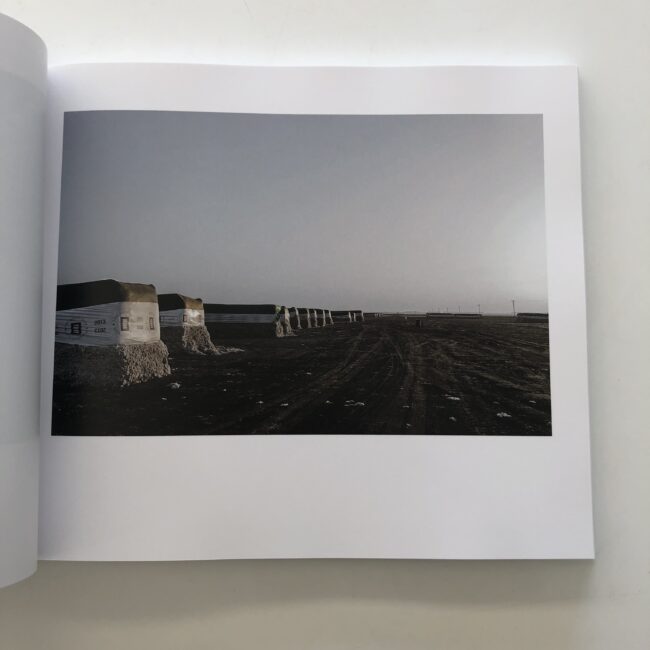

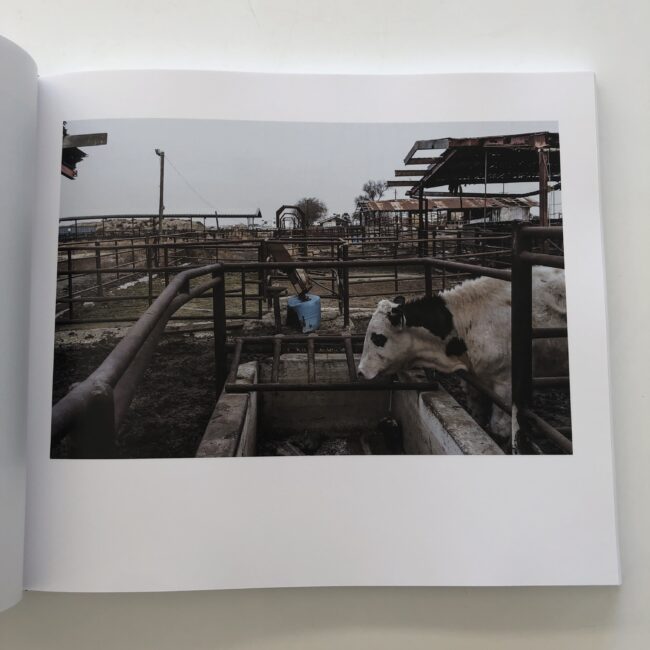

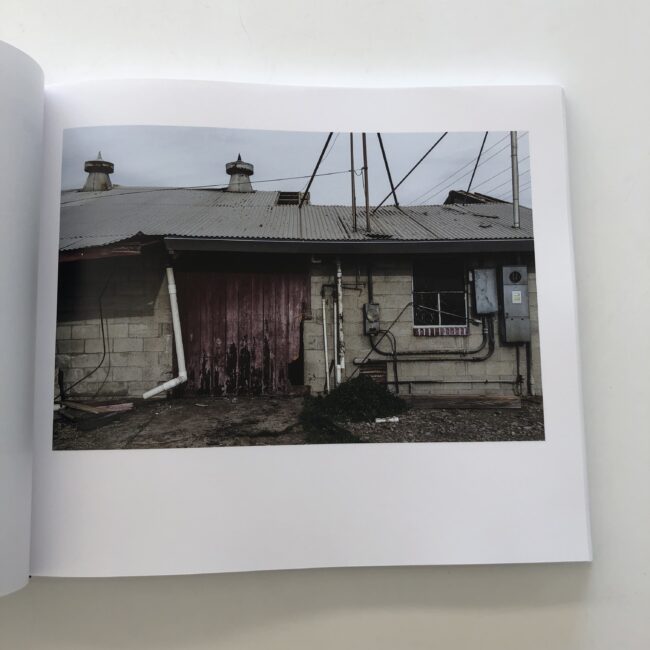

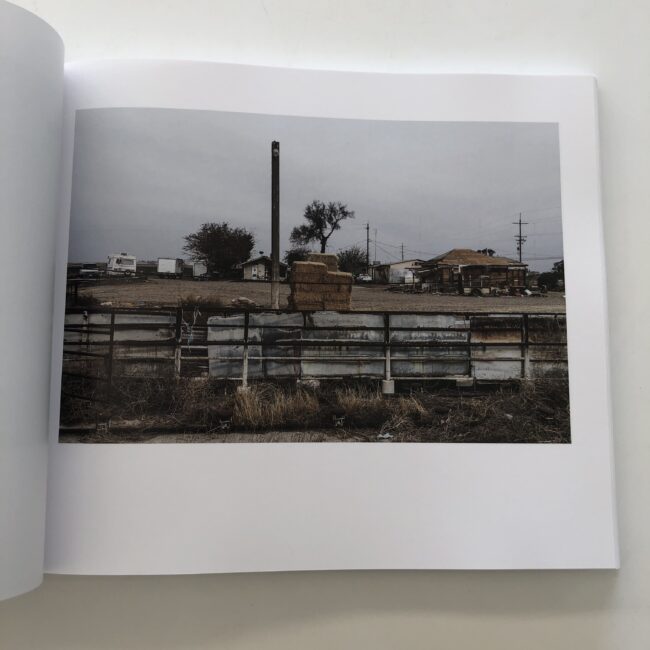

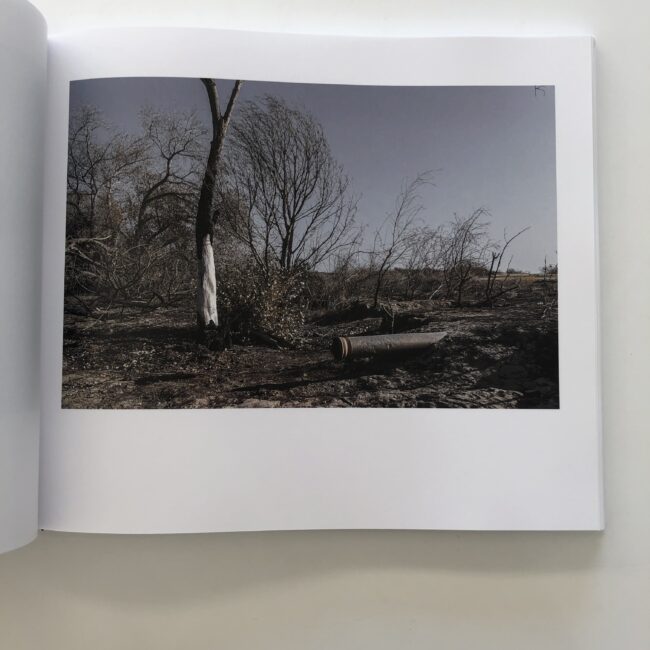

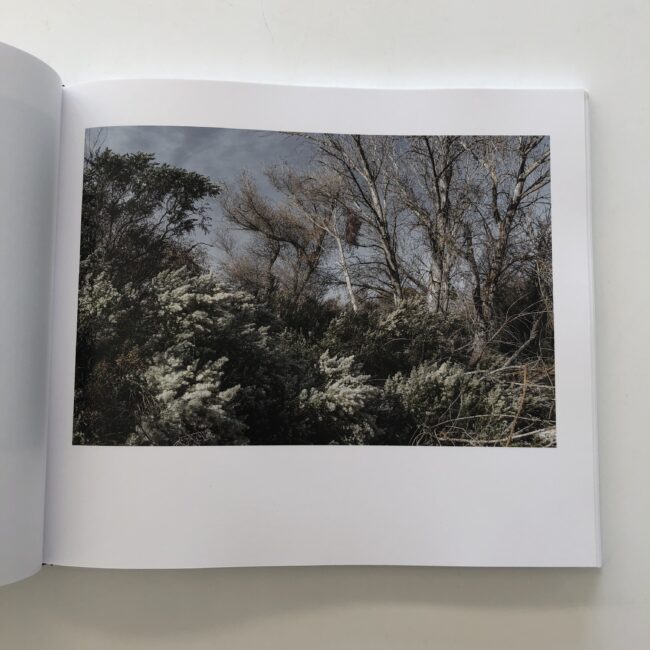

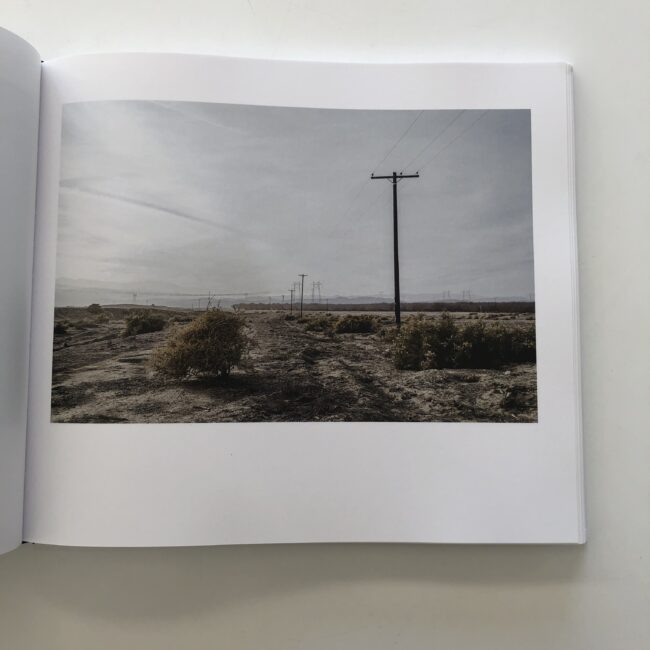

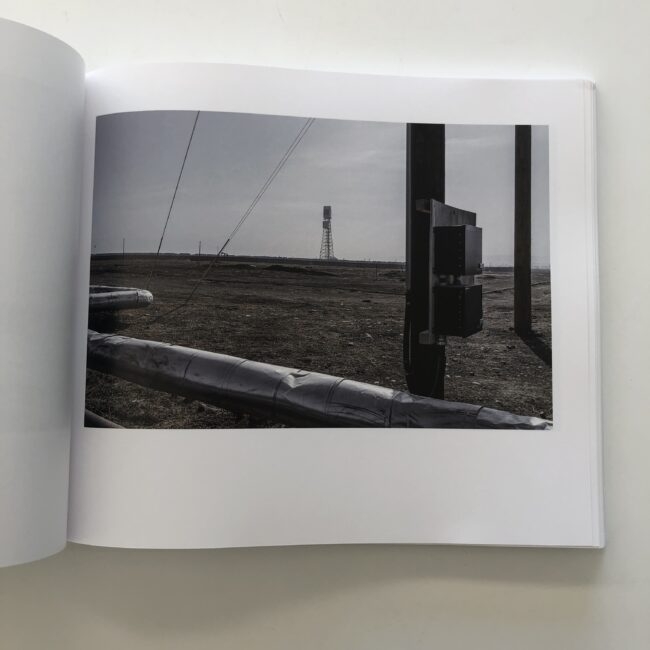

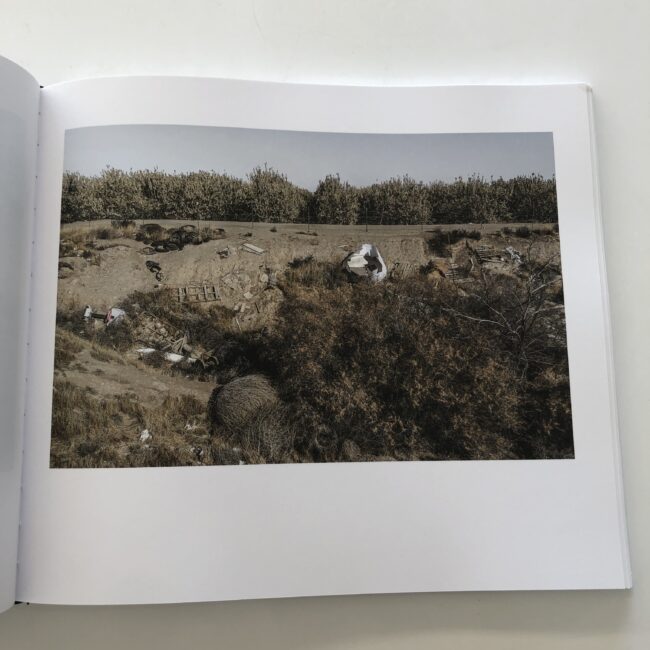

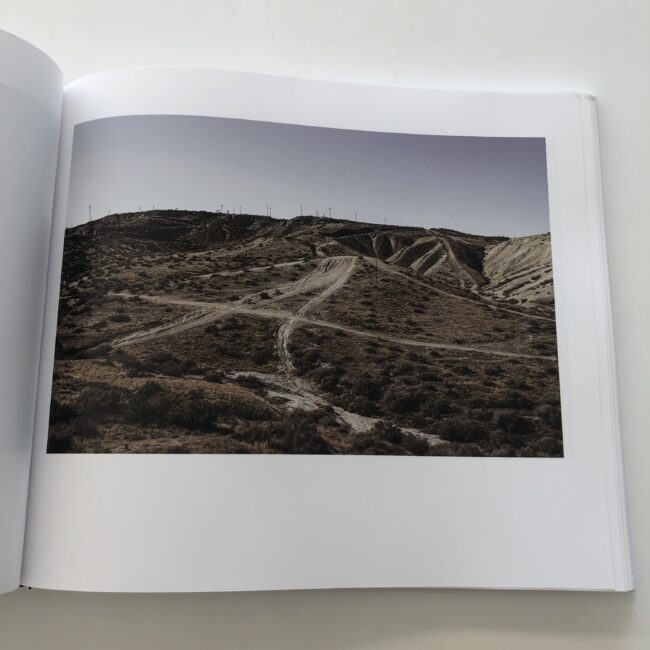

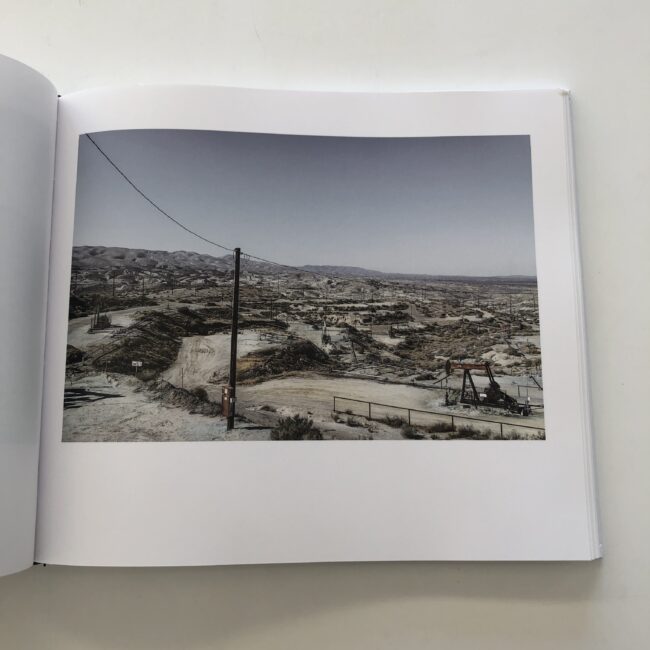

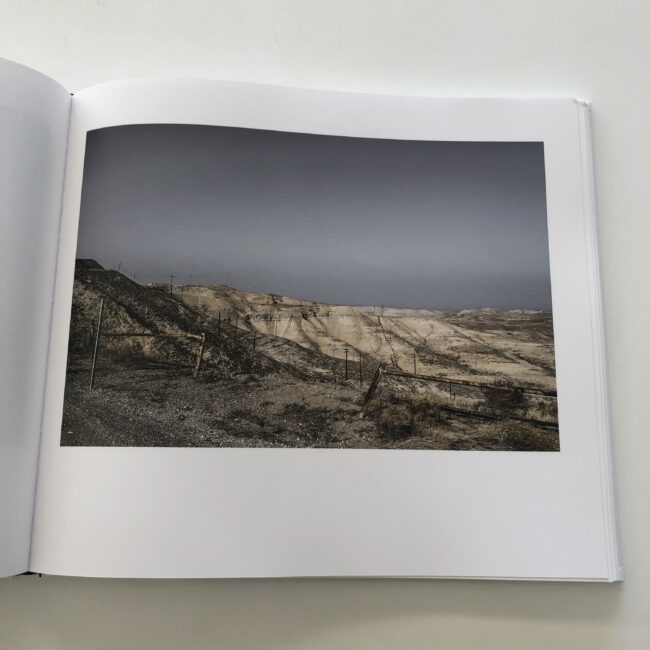

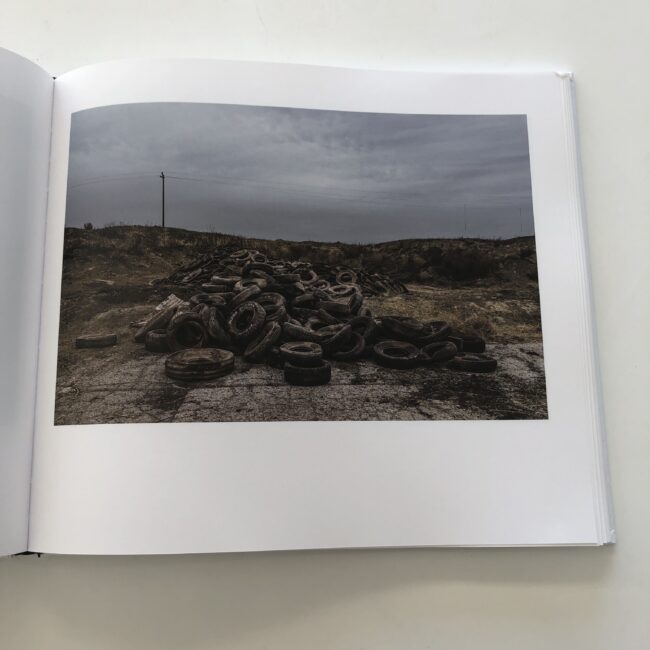

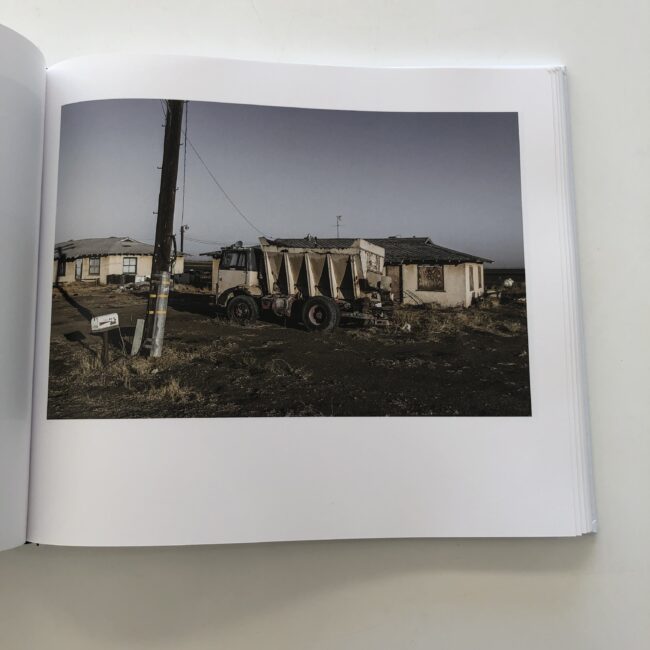

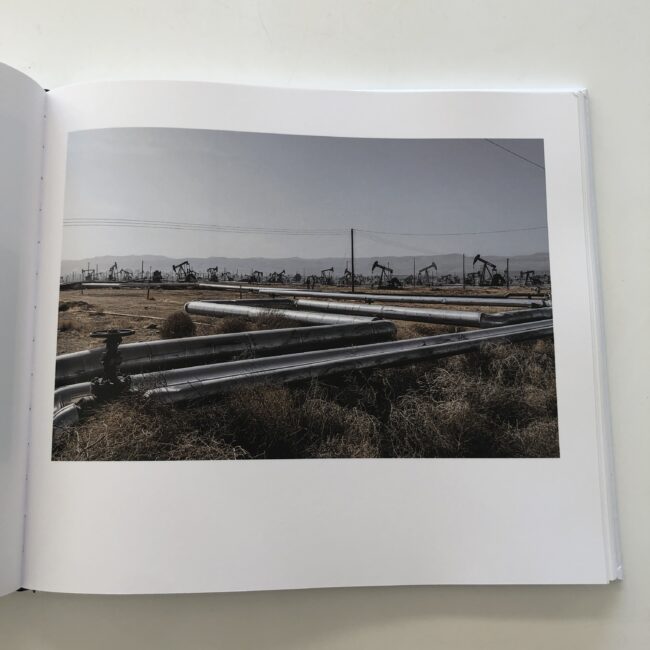

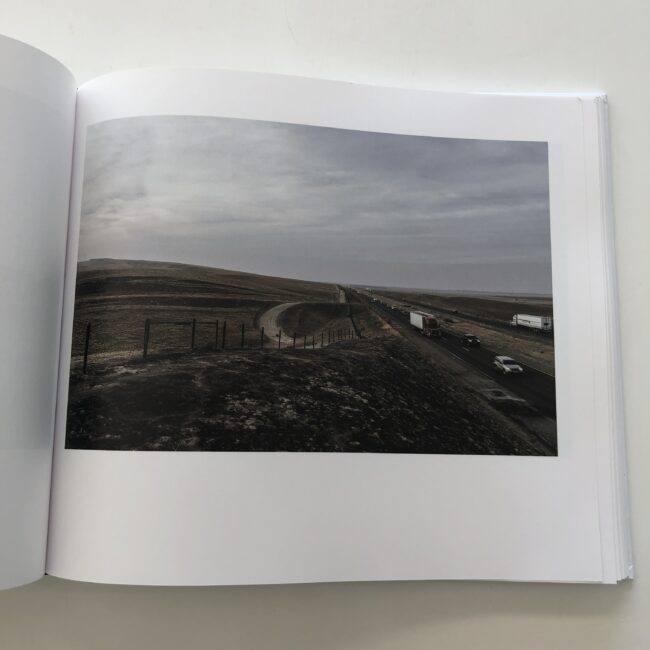

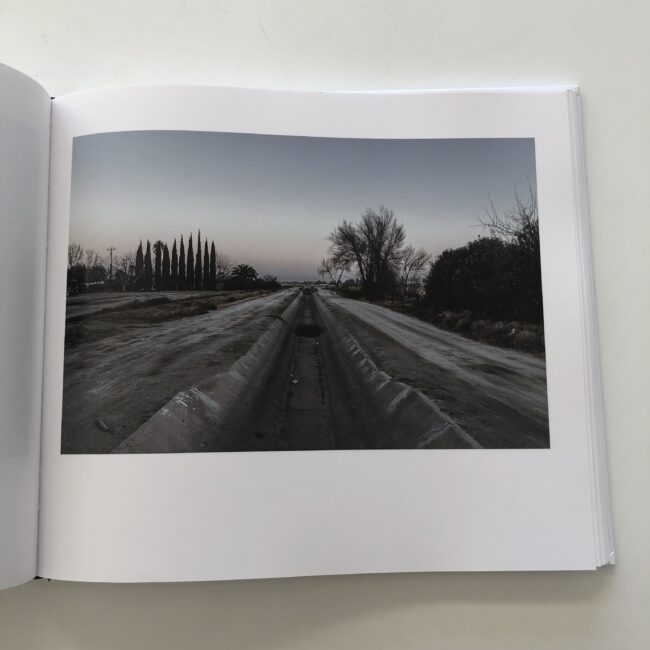

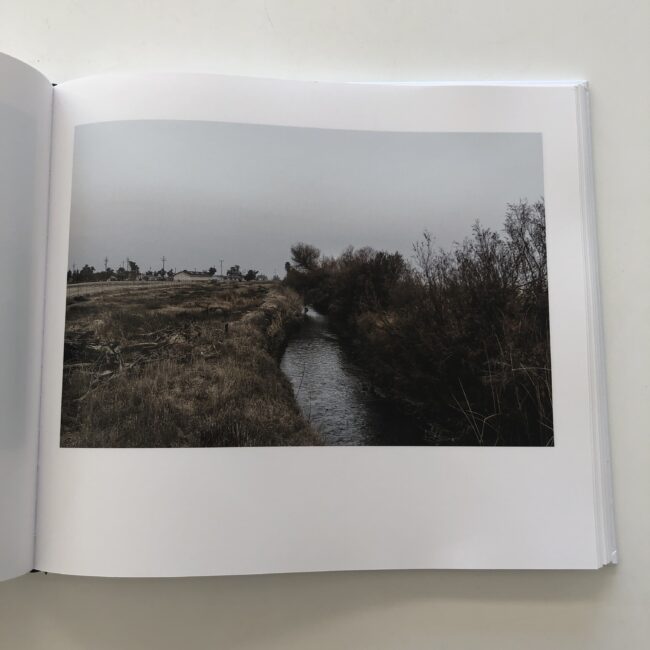

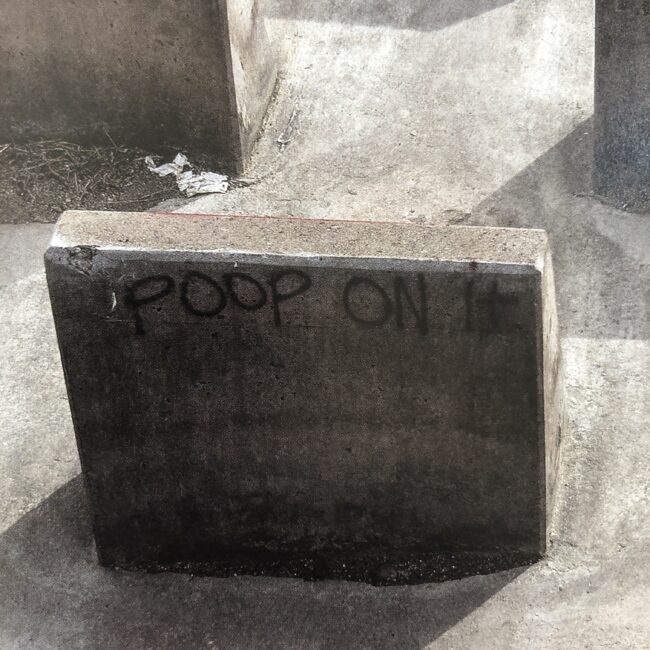

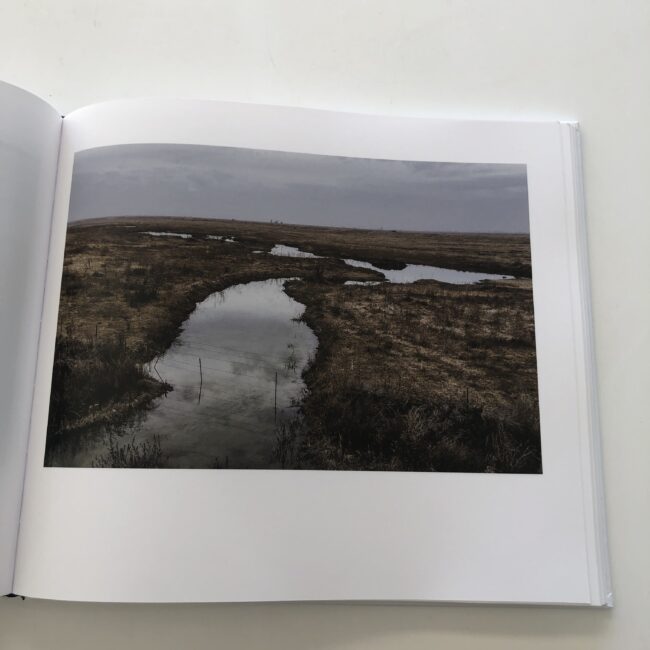

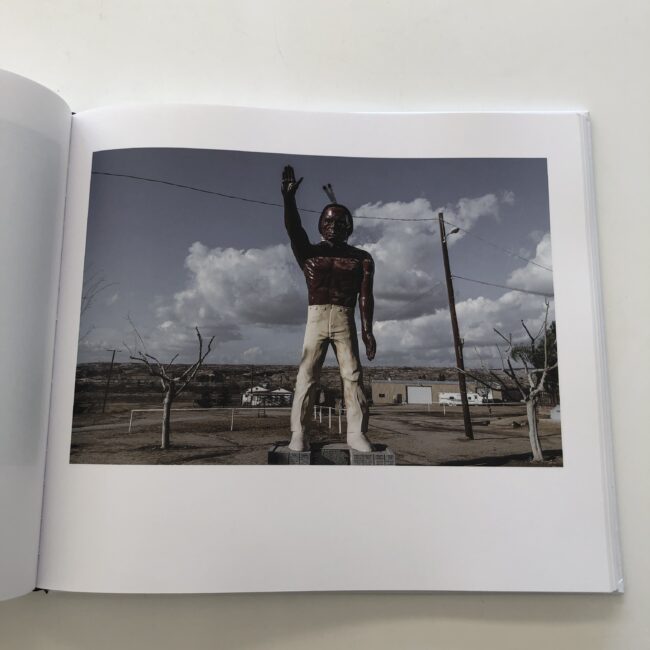

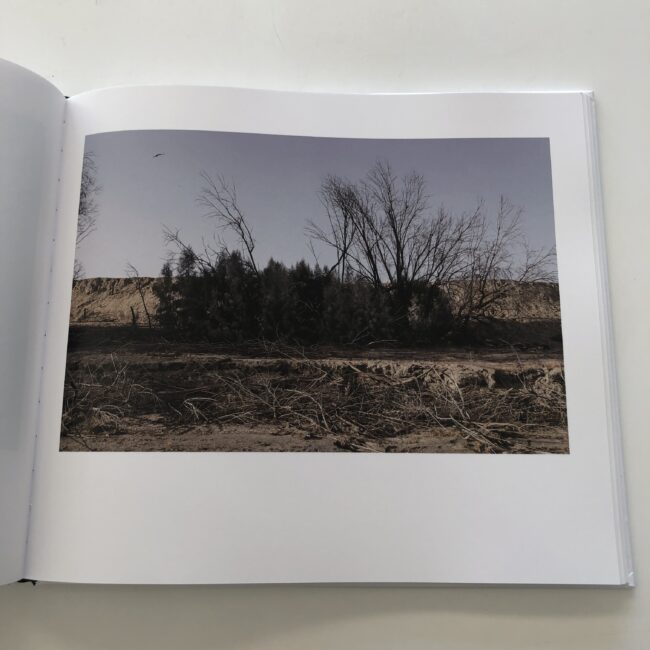

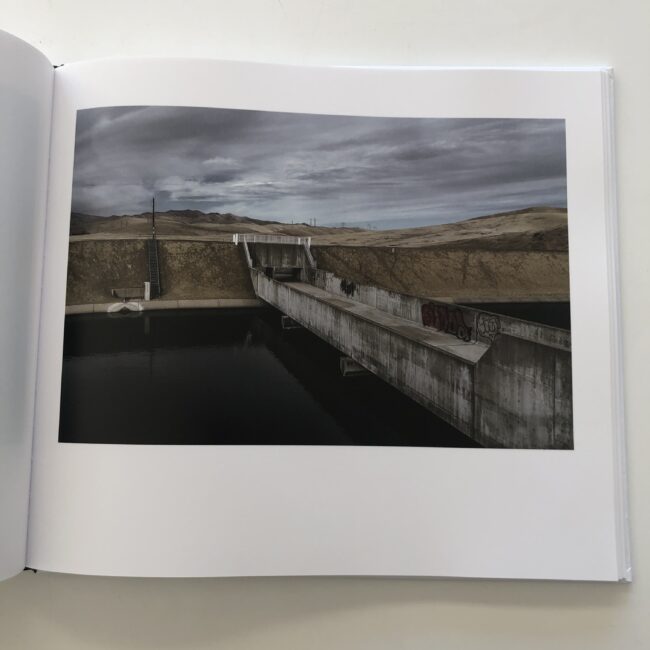

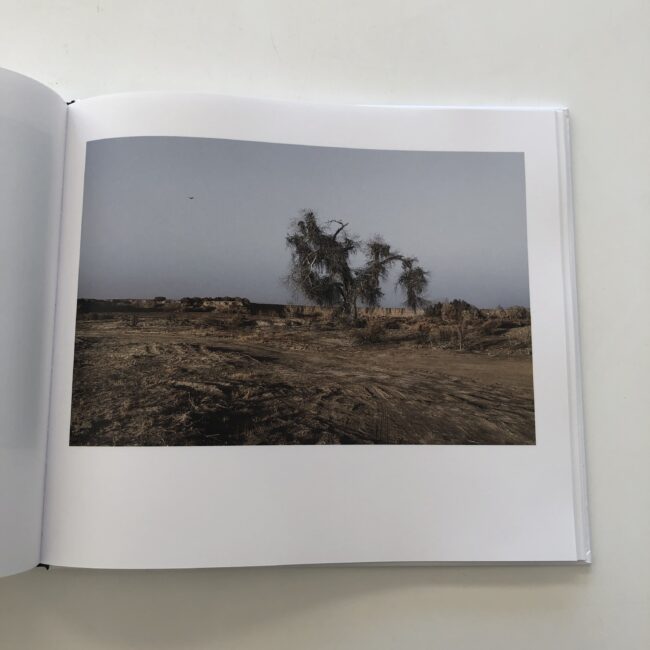

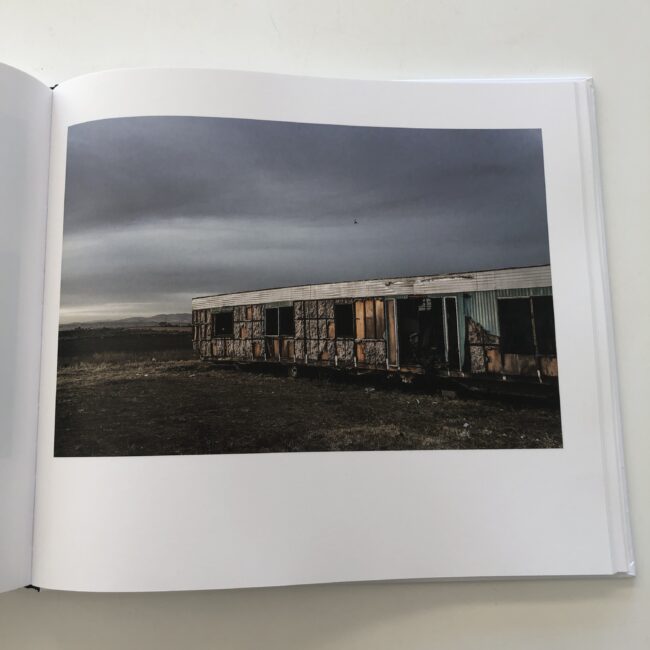

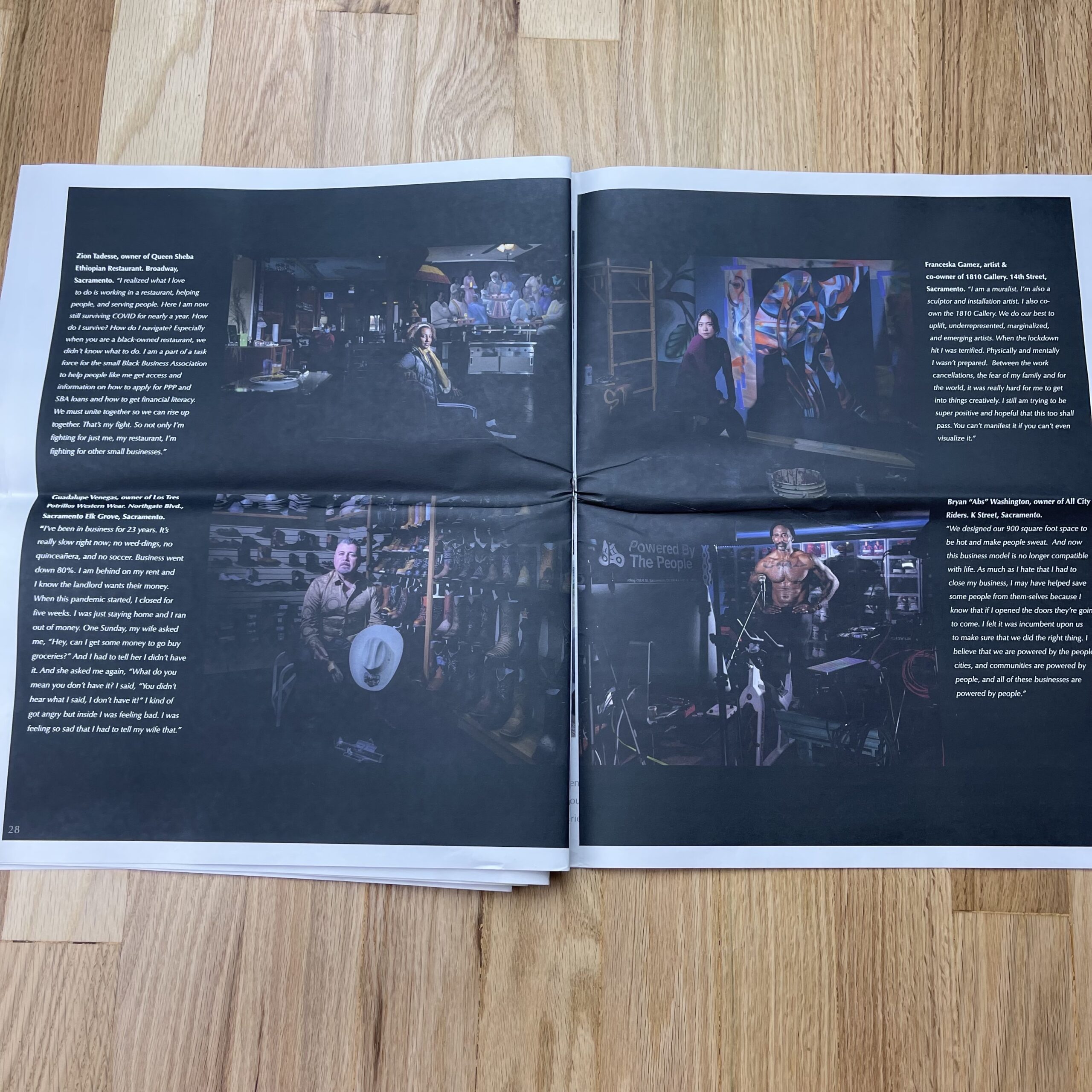

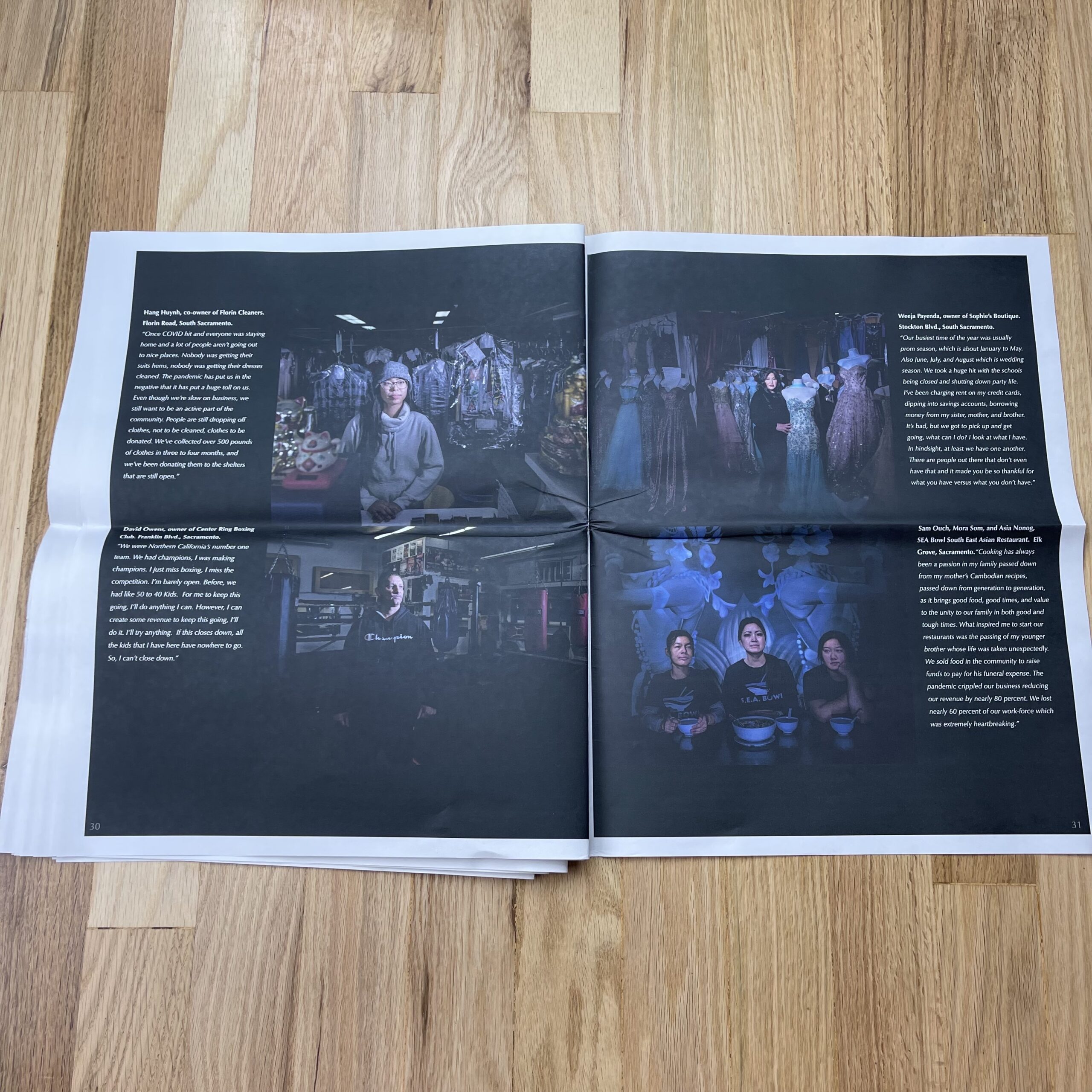

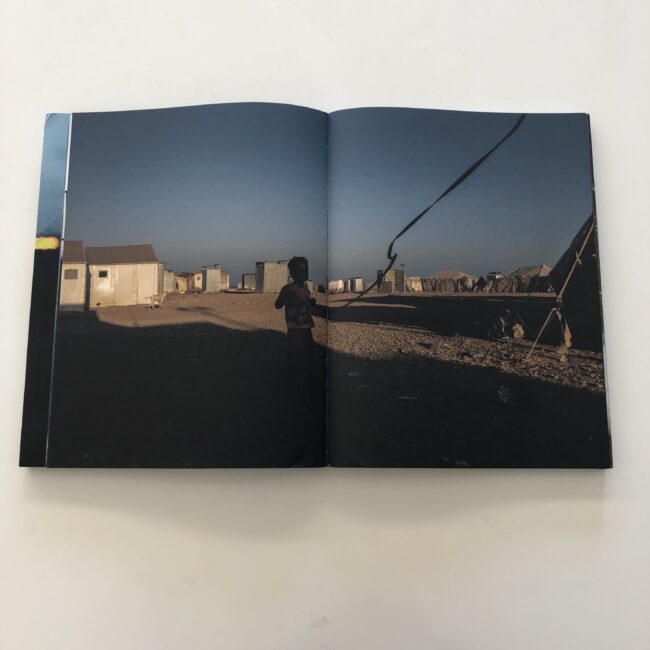

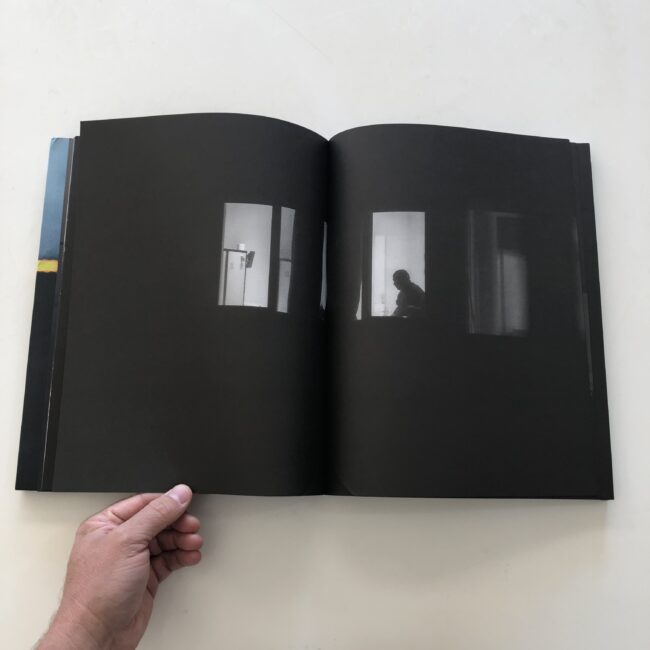

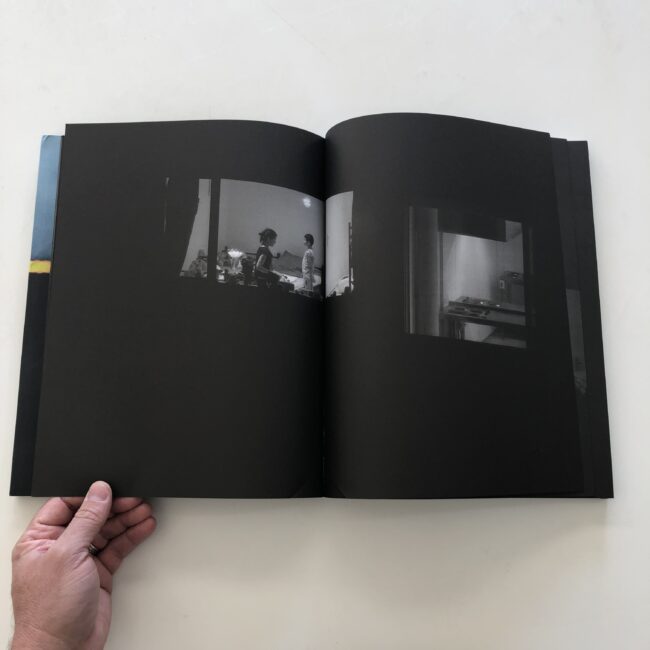

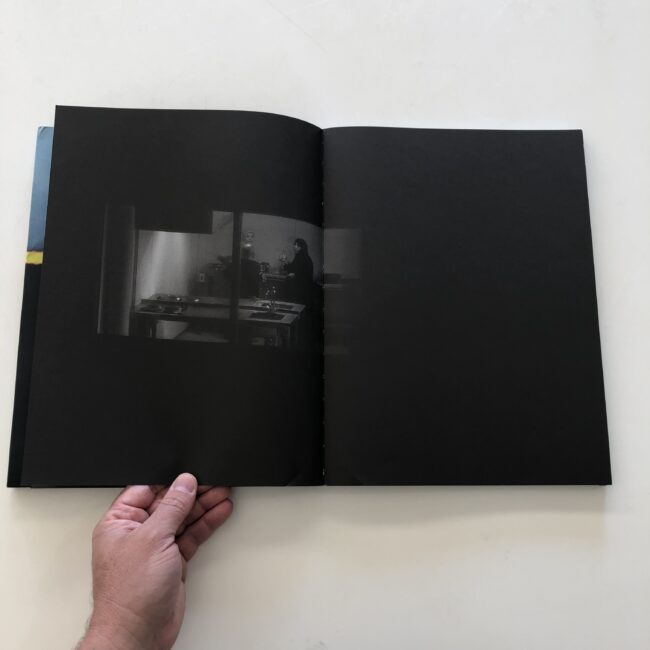

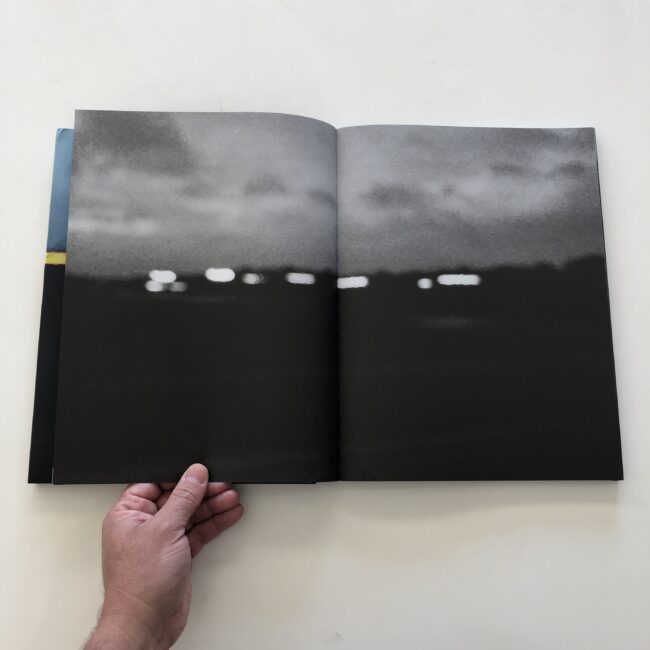

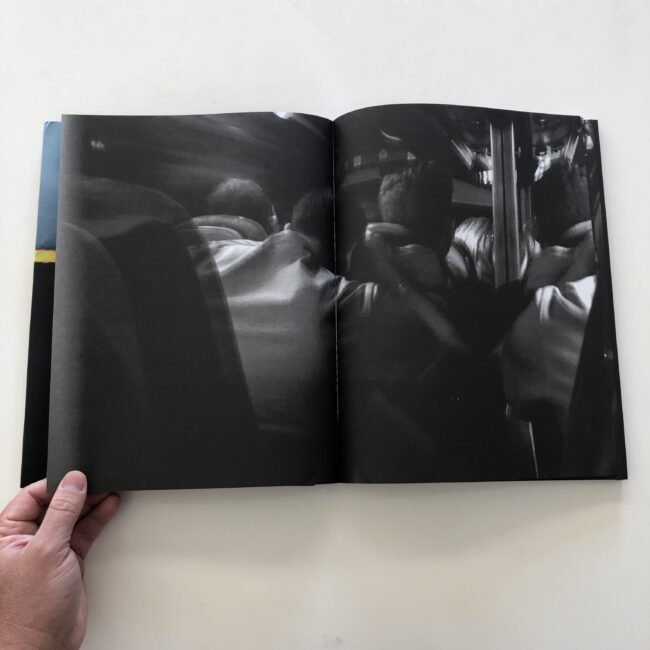

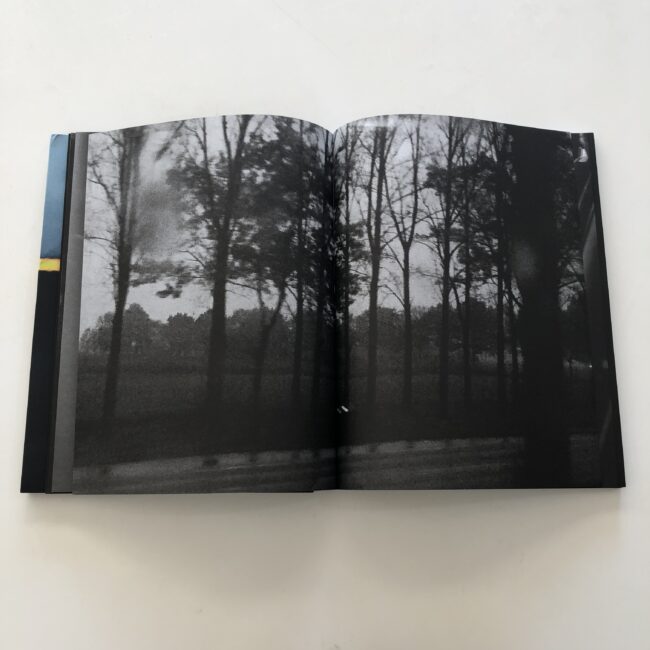

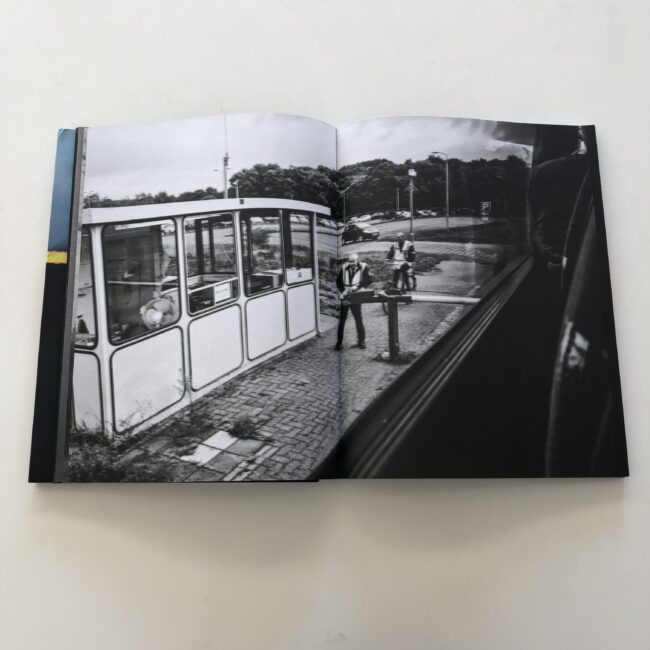

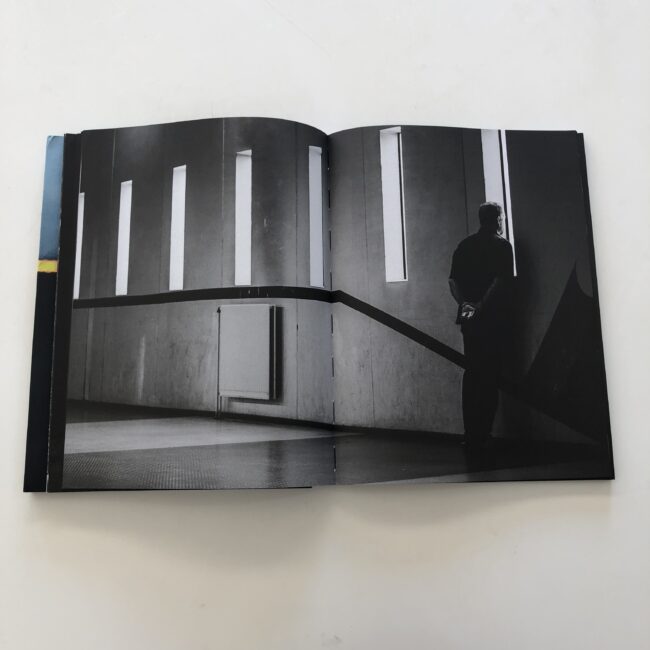

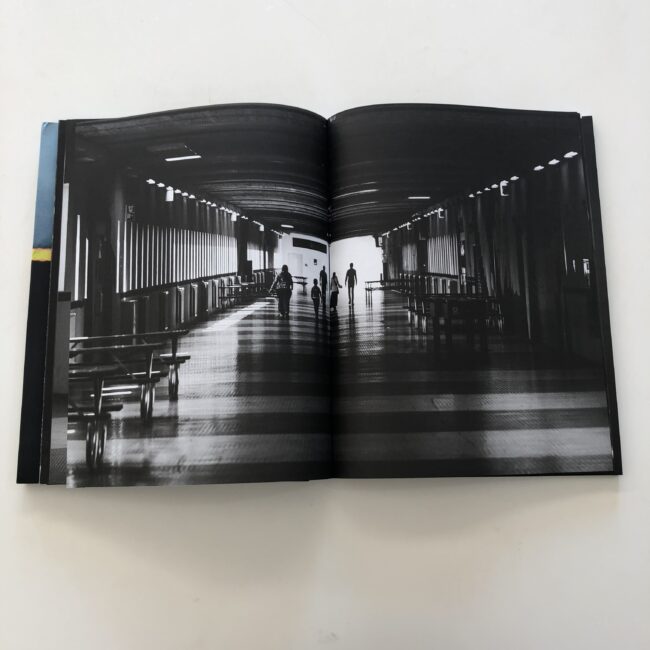

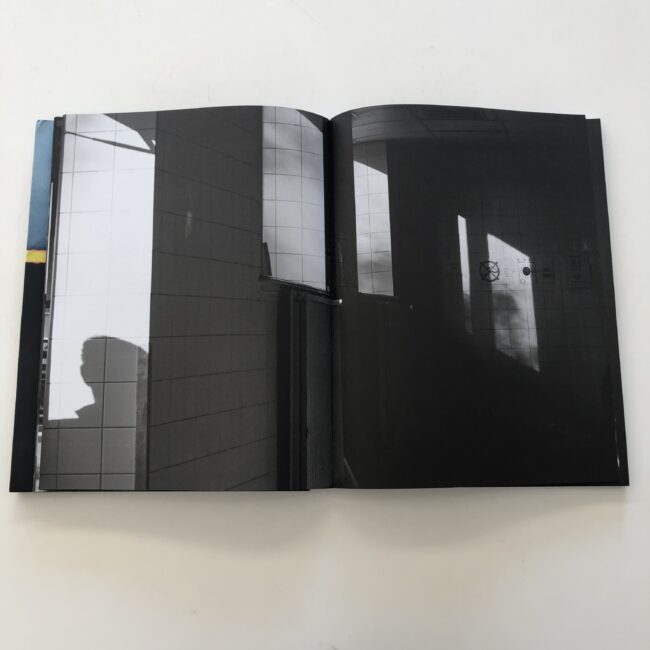

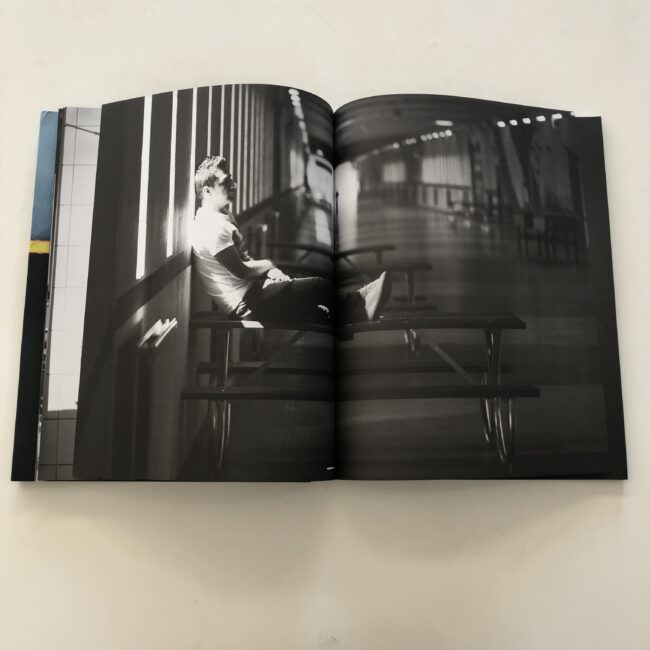

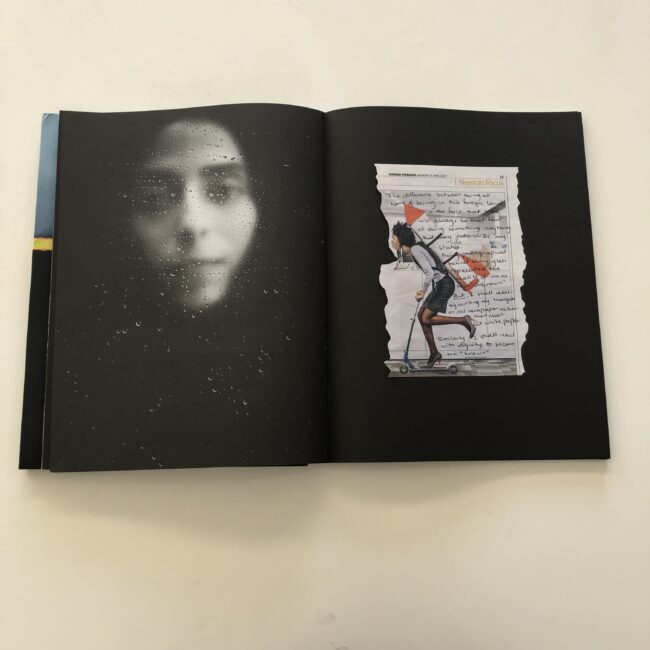

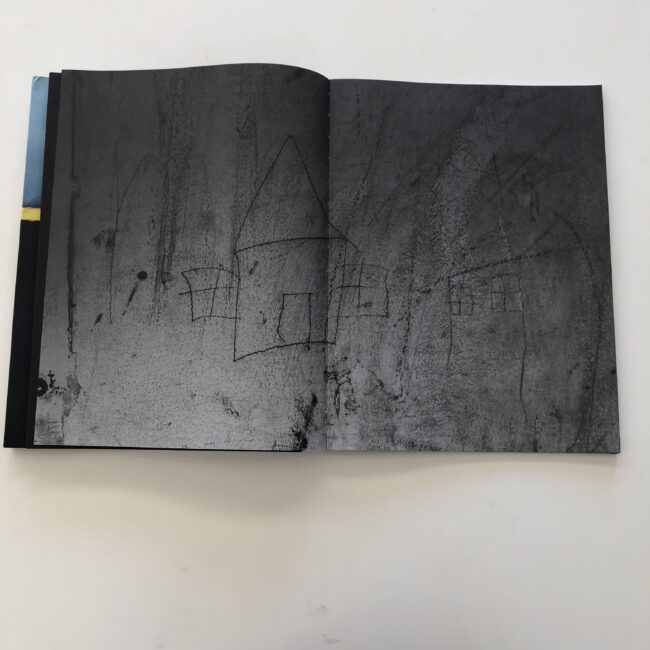

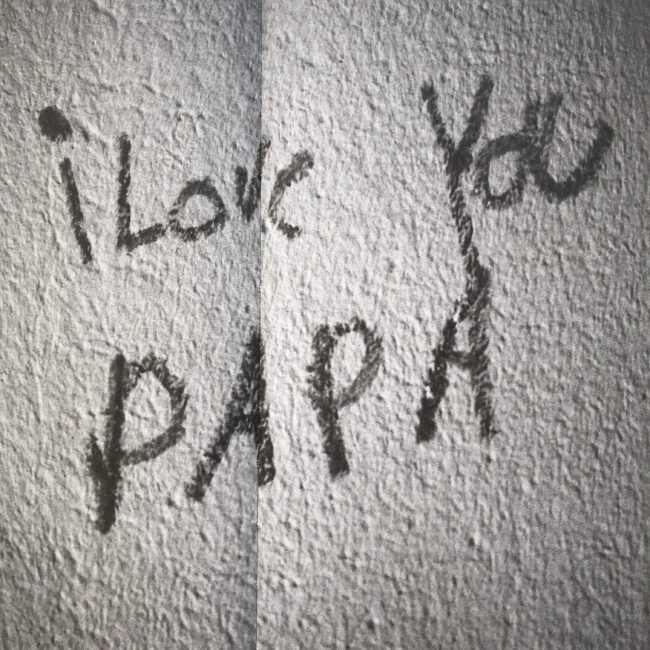

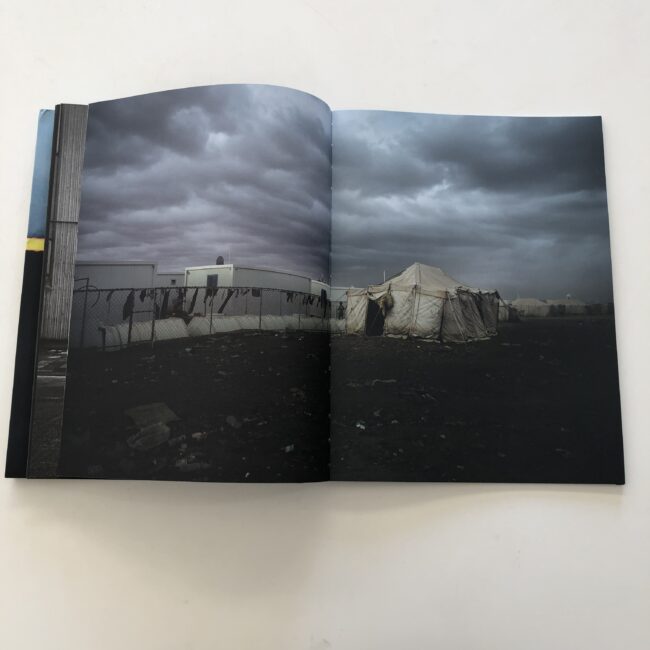

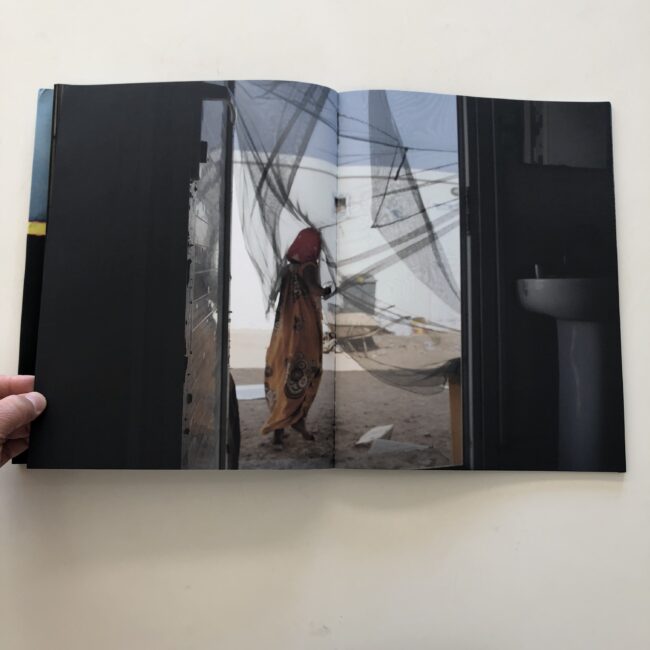

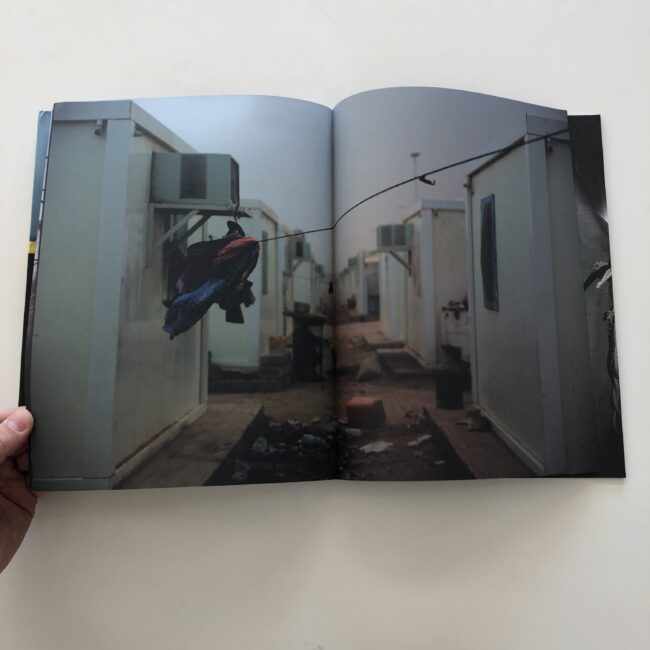

We see buildings, walls, hard-scrabble desert scenes, buildings, junk, trees, and occasionally, some people who don’t look at the camera.

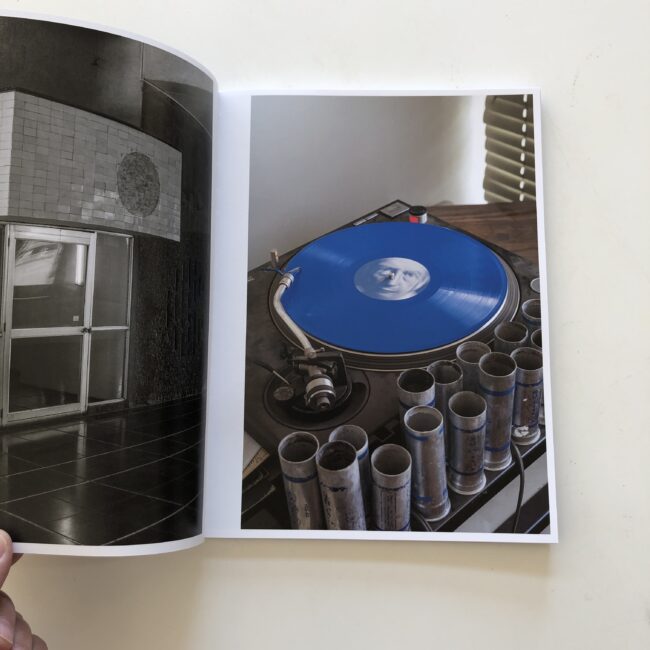

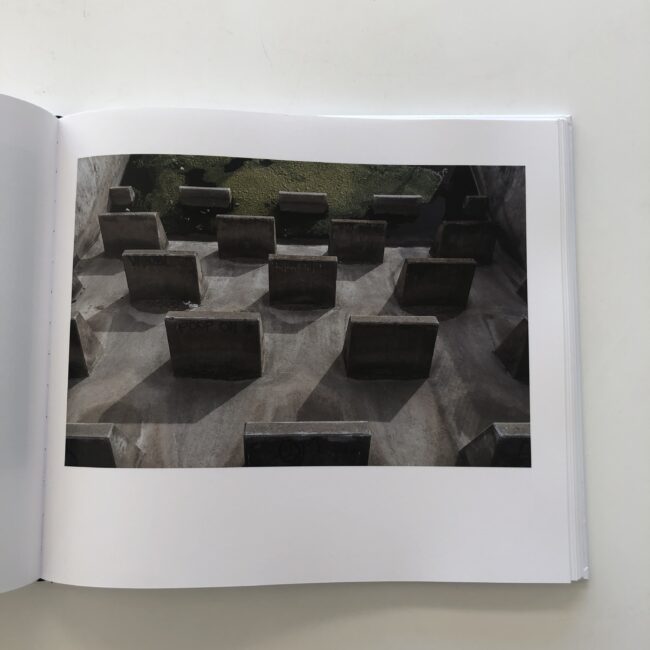

Circles form a repeating motif, including a cool image with a hole cut in a wall, and another with a record player sitting before metal tubes that remind me of pipe bombs.

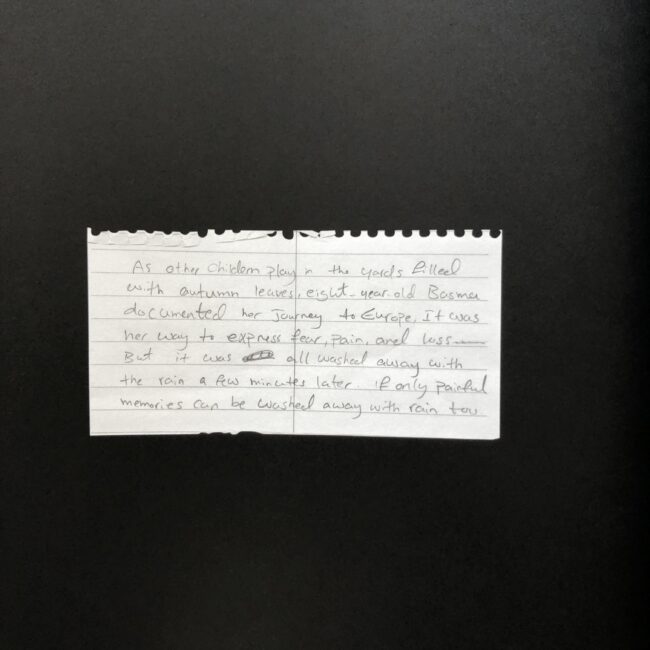

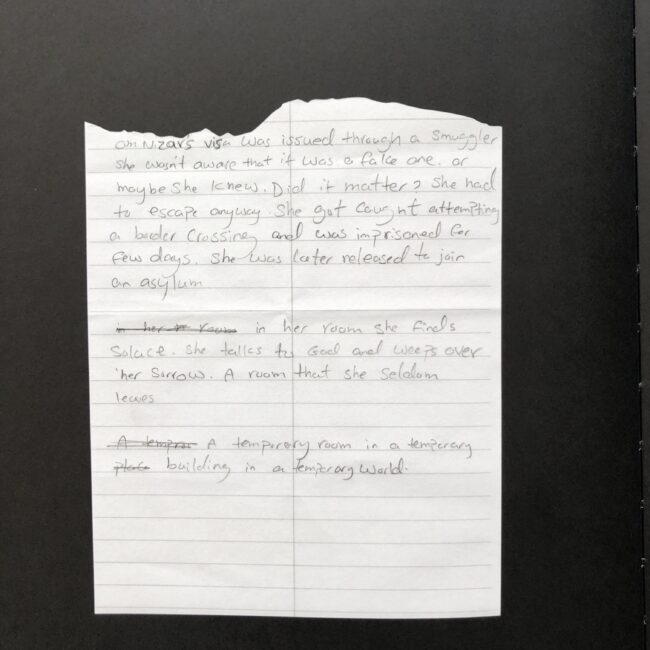

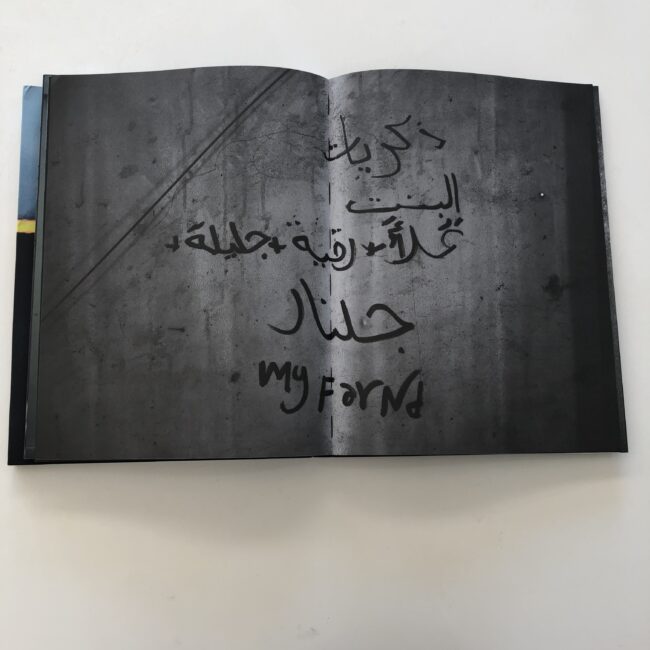

There are no words, until the end, and no context until then either.

Mostly, beyond thinking about Andy Kaufman, I realized the book was not really meant for me, as an American. (I know they sent it my way, but you likely catch my drift.)

It felt loaded with cultural references that I could not access, and the book also felt intentional about it.

As if creating a state of chaos and confusion was part of the book’s mission. Or perhaps it was commenting on a society that experienced those sensations, and the point of the art was to communicate that emotion through visceral means.

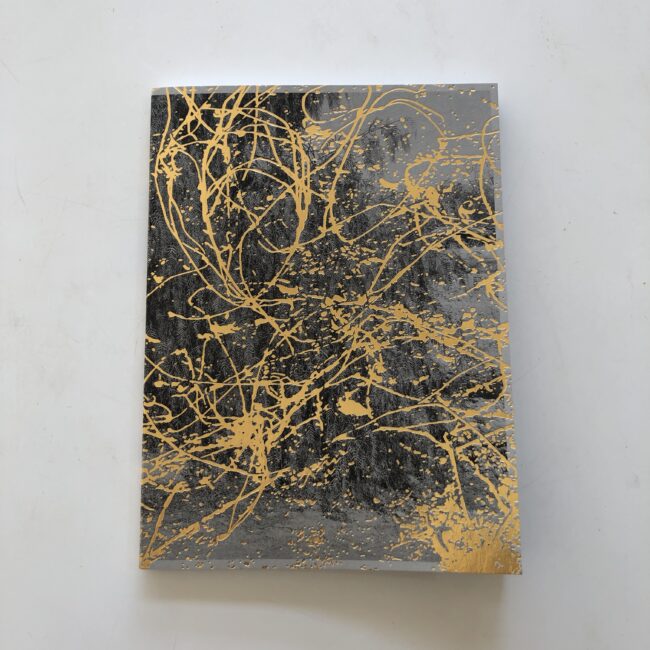

Furthermore, the production values are high, and the inclusion of images printed on vellum, as a way of breaking up the visual consistency, was great. (By not half-assing the production, it also lets a viewer know the project is serious, if inscrutable.)

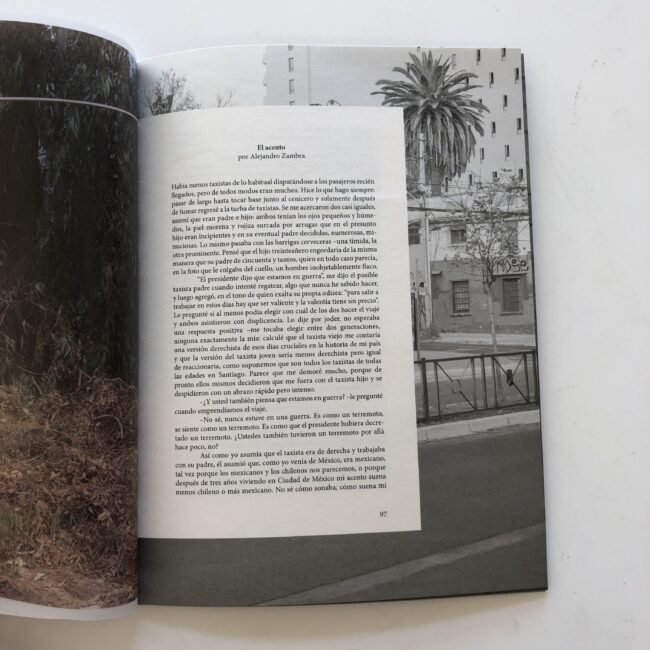

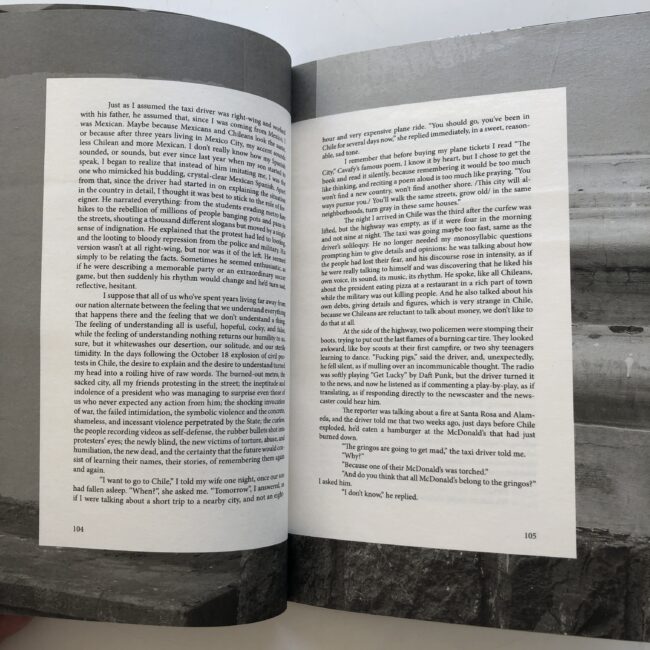

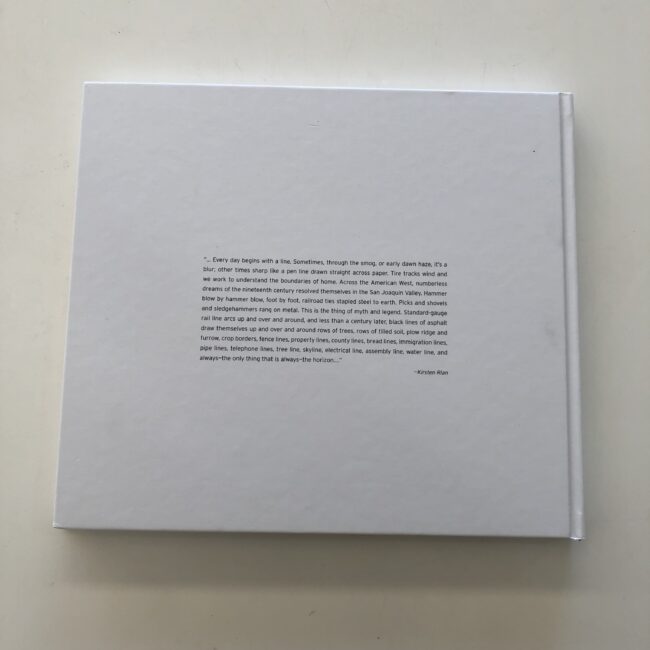

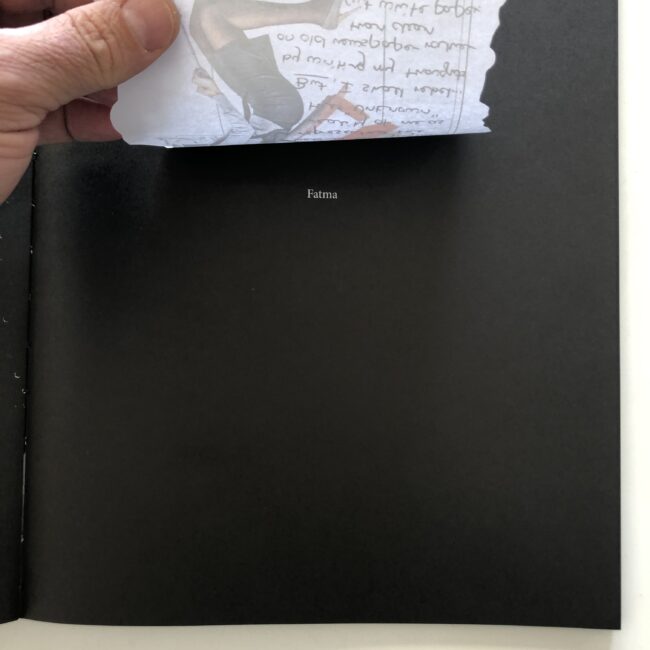

In the end, we get a long essay in Spanish, (of course, as I said, this was not designed for Americans,) and then a translated version.

It’s by Alejandro Zamba, and quickly establishes the book is about Santiago, Chile, not long after the city erupted in protests, violence, and social disorder, not unlike what happened in the US in 2020.

It’s a beautiful short story, almost in the form of a parable, as a stranger lands at an airport, and takes a long taxi ride, during which the driver catches the author, (and we, the viewer,) up on what the book is actually about.

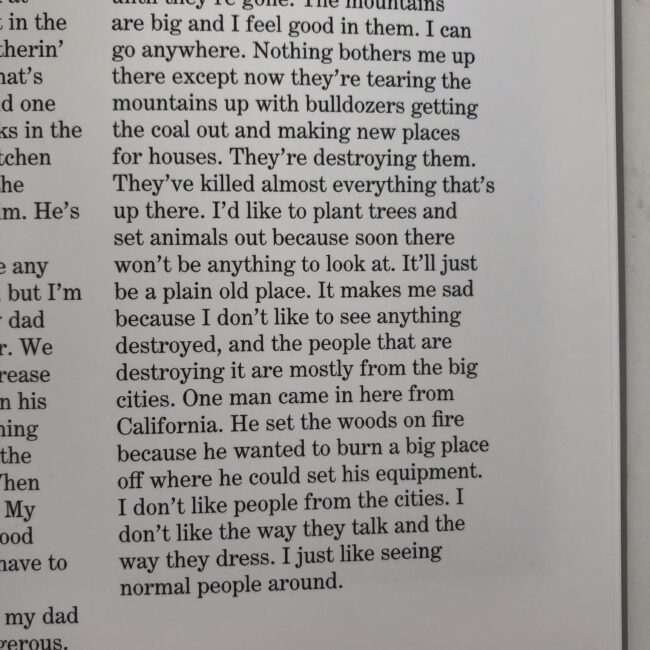

There’s a quote within, which summed up my feelings about our innate human desire for things to make sense: “The feeling of understanding all is useful, hopeful, cocky and false, while the feeling of understanding nothing returns our humility to us…”.

I must say, one of my very favorite things about this job is that I get to learn about faraway places, and share that knowledge and “intel” with you.

The end notes tell us this project was supported by a publisher in Italy, foundations in Luxembourg, in conjunction with Les Rencontres d’Arles in France, but what that has to do with a Dada book about Chile, I cannot say.

Only after I was done did I notice some press materials that likely tried to explain things, including an essay by Adam Bell, but it was pointedly not included in the book. Nor was it an insert.

So I didn’t read it.

I’m not being petty, though.

Rather, I was luxuriating in the not-knowing. In being reminded I’m just a puny human, living for a short time on a spinning rock, hurtling around a star in an ever-expanding Universe.

And so are you.

To purchase Providencia click here