I’m keeping it super-short today.

(Like, for real.)

If all goes well, as you read this, I’ll be on my way to Amsterdam to supervise printing of my first book.

I’m a ball of nerves, if I’m being honest, but the upside is, I’ll have lots of new things to write about for you.

Between the global panic over the corona virus outbreak, and the fact that I’m flying into a bomb cyclone hurricane, (Storm Dennis,) I think you’ll allow me a rare quickie.

To balance the brevity, though, we’re going heavy.

Here’s the rub.

In the middle of #2019, well before I began doing book reviews again, NYU Professor Lauren Walsh, whom I’d interviewed for a story before, reached out to see if I’d be interested in seeing her upcoming book about conflict photography.

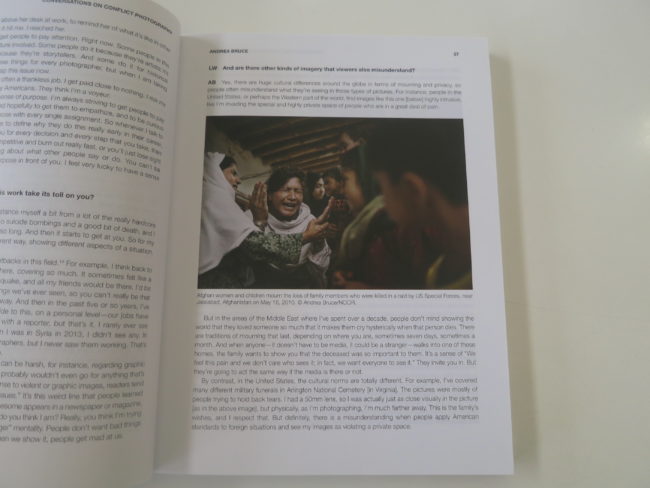

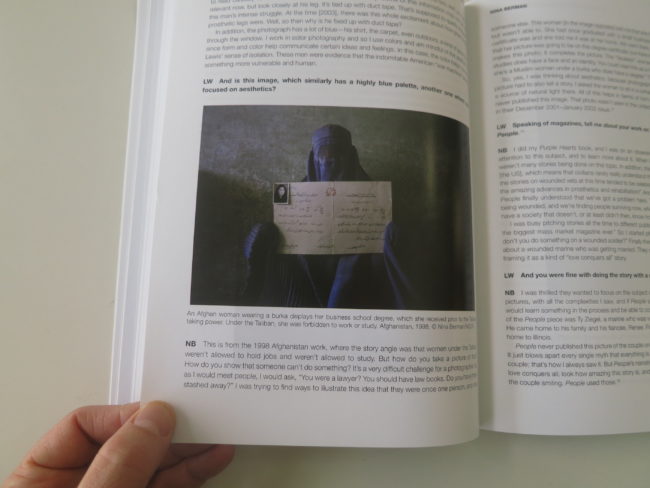

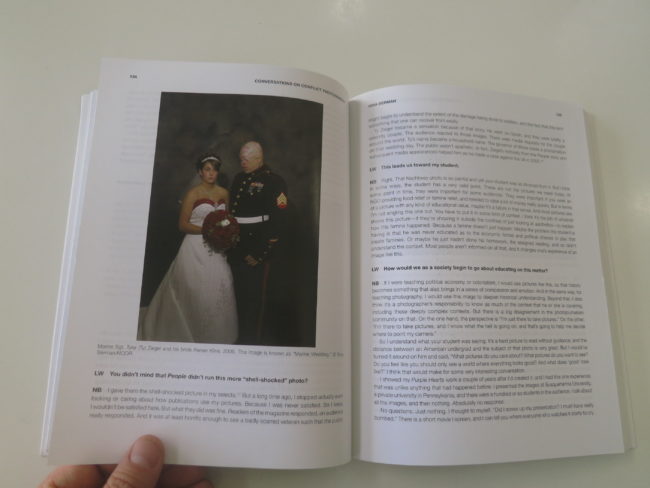

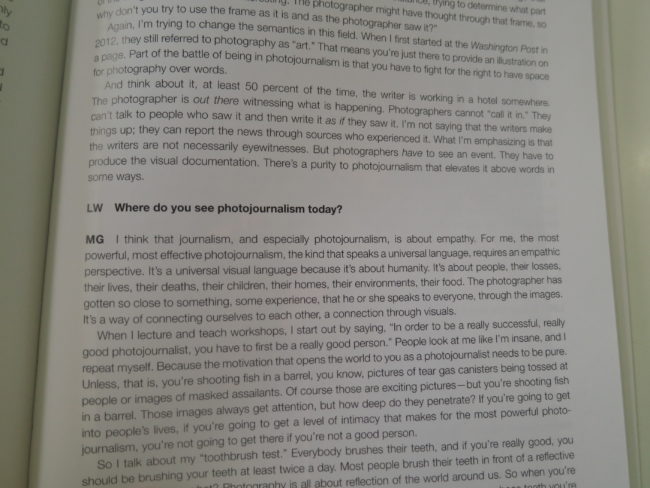

She long-form interviewed a host of the top names in photojournalism, including photographers like Nina Berman, Ben Lowy, Susan Meiselas and Shahidul Alam, and editors like Santiago Lyon and MaryAnne Golon.

(Top, top people.)

I told her I wasn’t reviewing books for a few months yet, and had almost never reviewed text-dominant books before, outside of a few rare exceptions.

Undaunted, Ms. Walsh sent the book, content to wait six months for a review, and then she followed up several times thereafter.

Finally, I took a look and tried to read it, but it didn’t grab me in the “right” way. I kept getting bogged down, perhaps because I’d interviewed several of the people before, and did these types of interviews myself, here, for years.

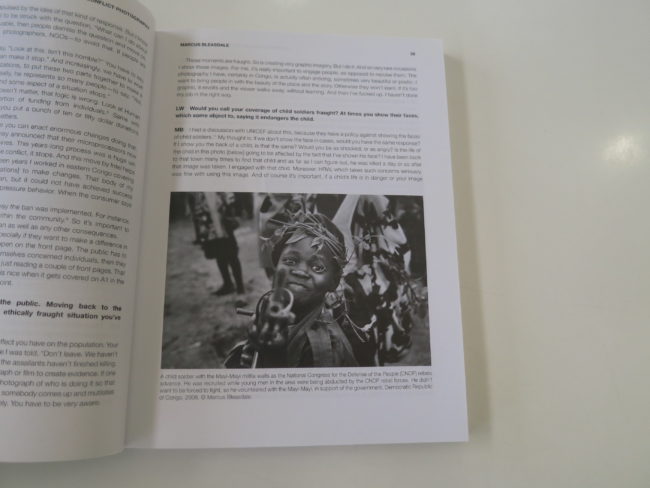

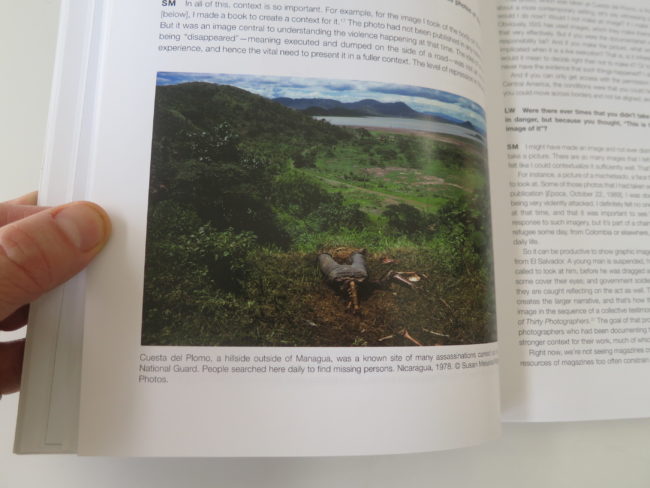

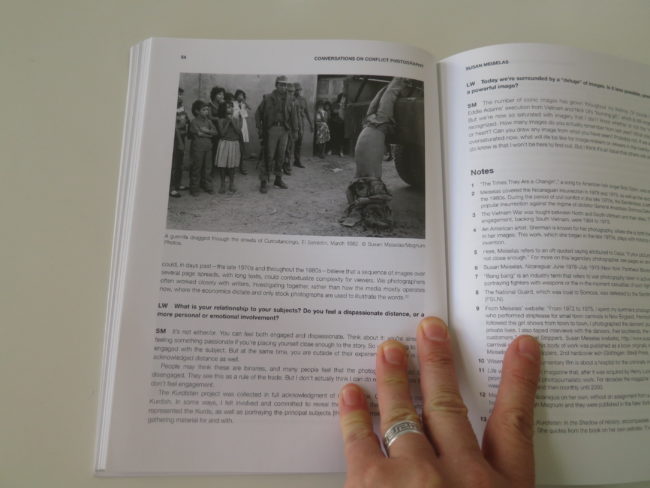

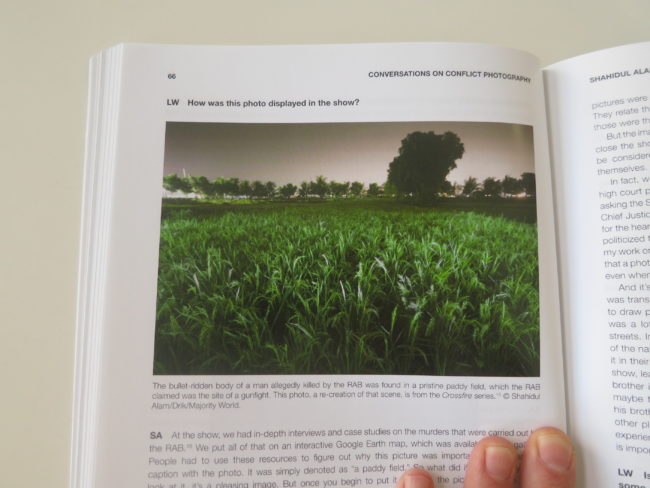

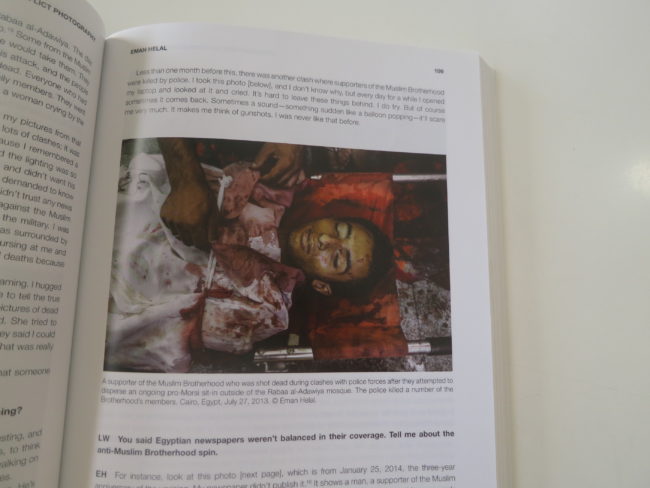

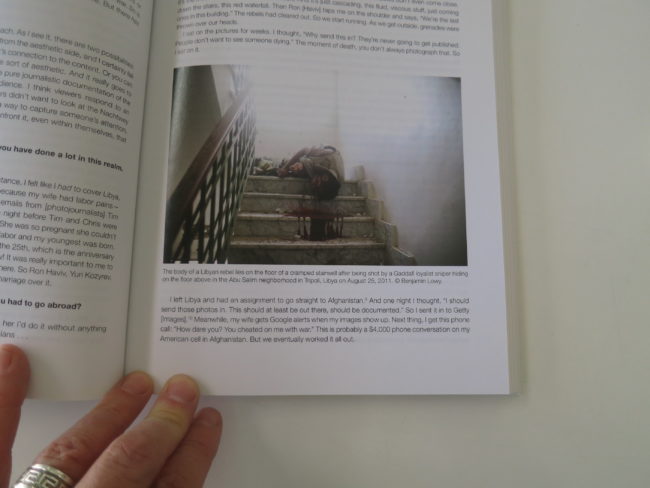

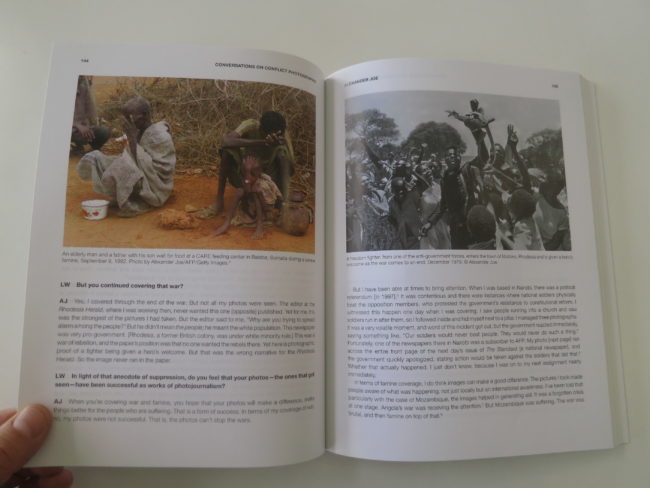

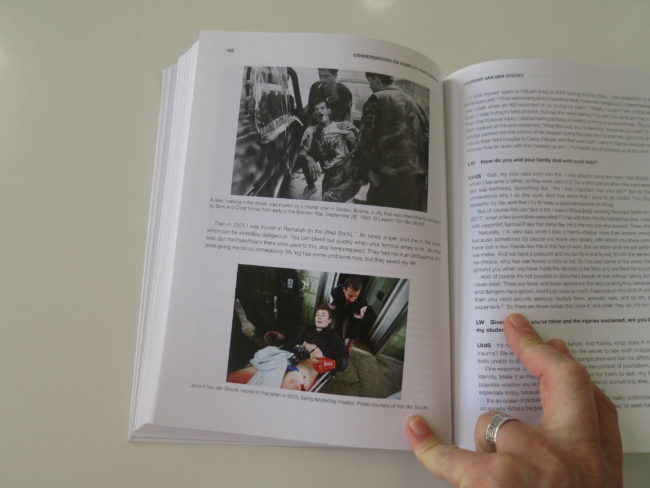

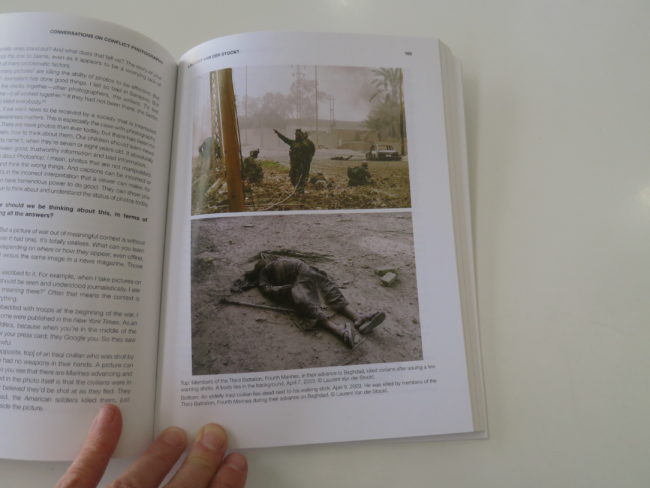

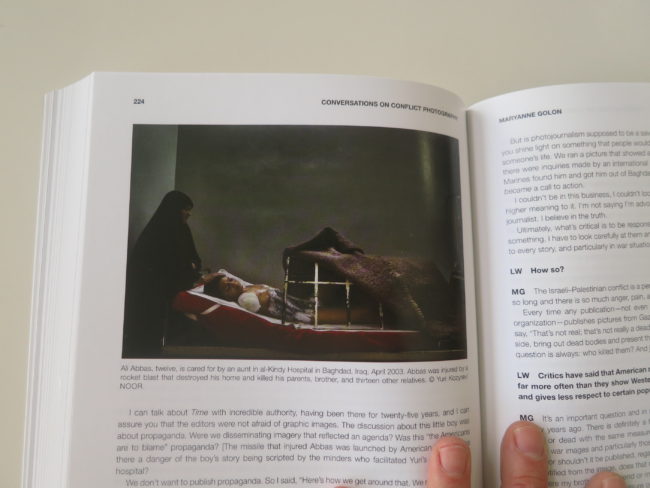

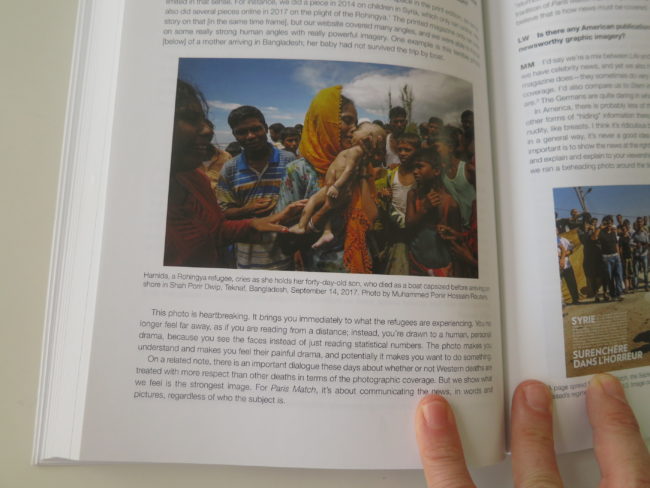

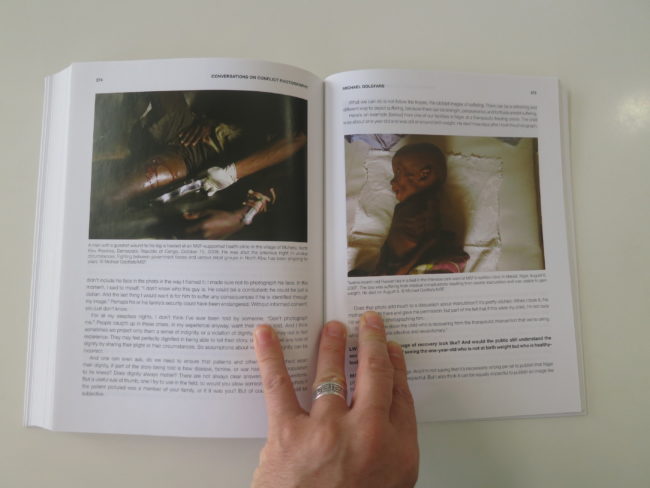

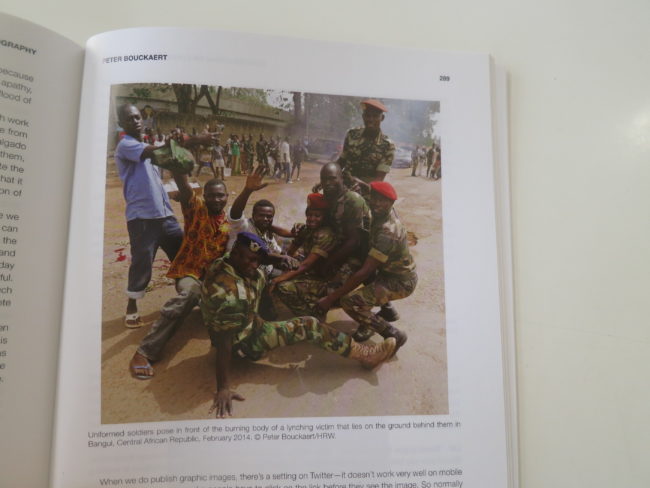

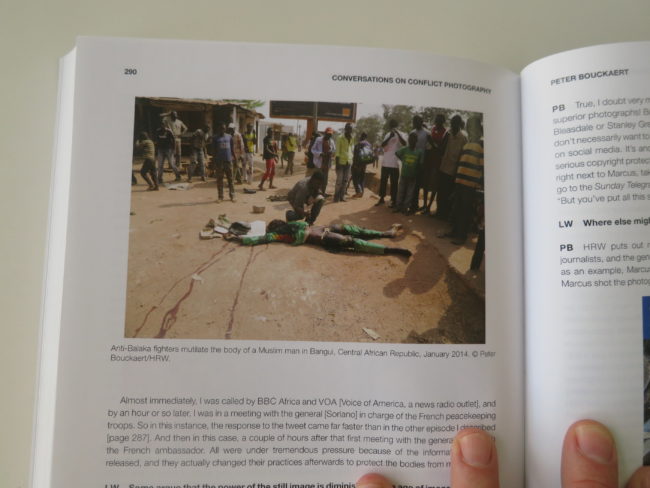

And the pictures are so hard to look at, this being a book about conflict journalism.

It was easier not to engage.

(And isn’t that just a metaphor for all of it.)

I wrote to Professor Walsh to apologize, and say, “Sorry, this one’s not for me.”

In reply she asked me to reconsider.

“Perhaps,” I said, “I’ve done it before,” and here we are.

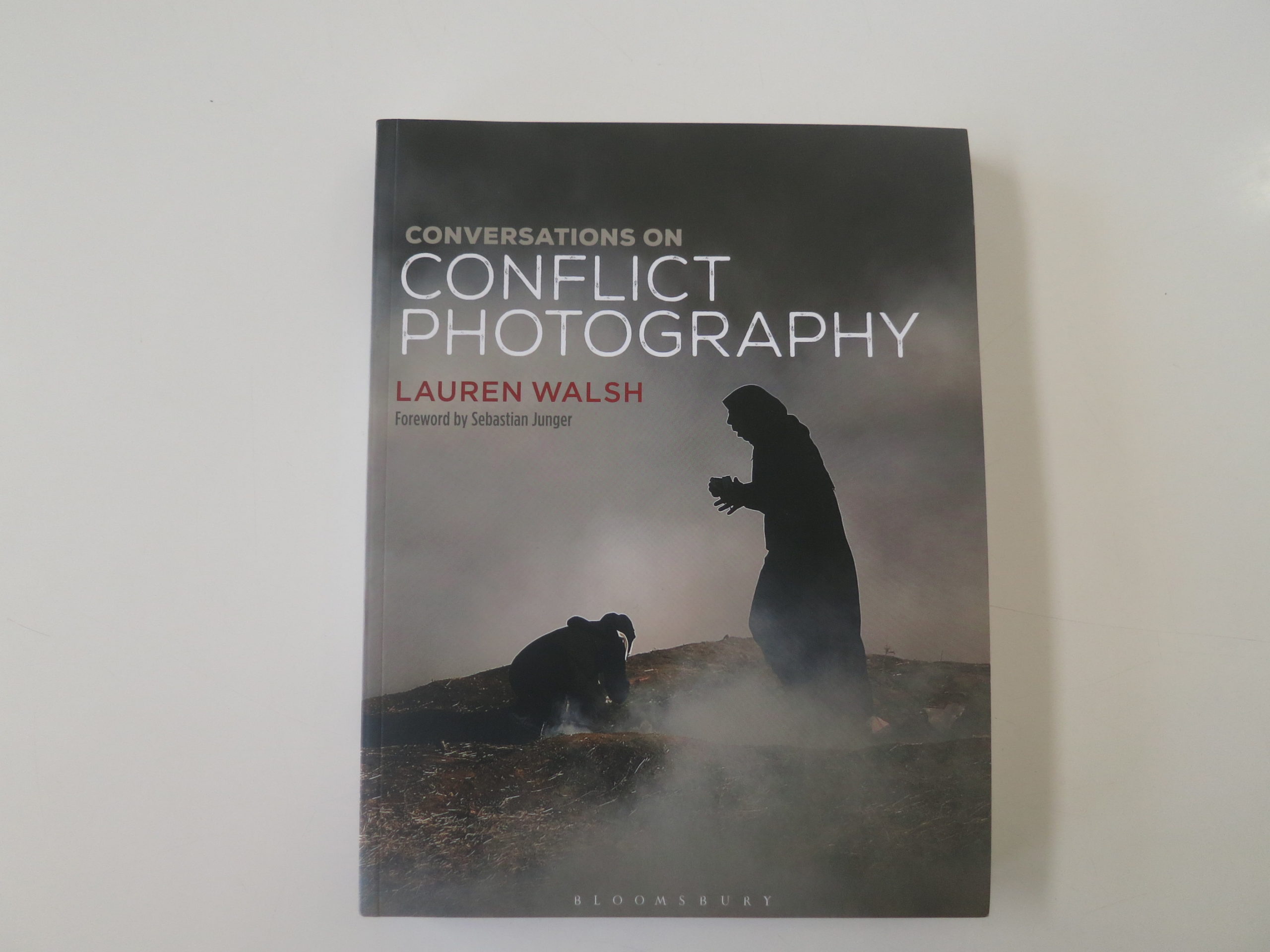

“Conversations on Conflict Photography” by Lauren Walsh, was published last year by Bloomsbury. And when I took another look at it yesterday, I realized it was something worth showing you.

It’s just not what I first expected it to be.

You don’t have to read it cover to cover in one sitting.

It’s not meant for that.

Rather, I began to think of this book as a resource, to be sought out for knowledge for anyone learning the craft; a guidebook into a vital segment of the photo industry.

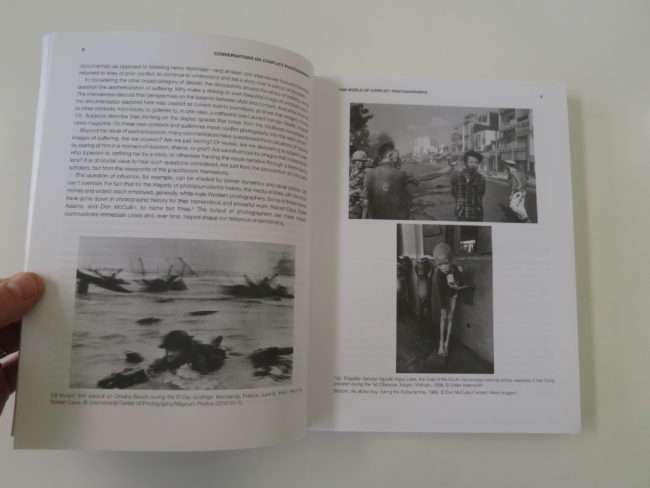

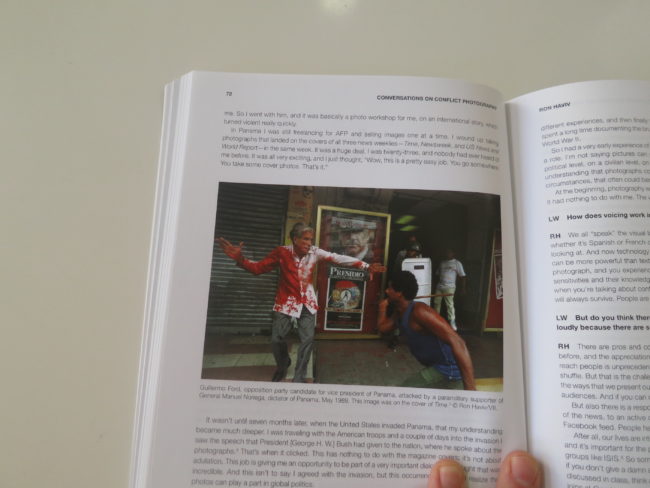

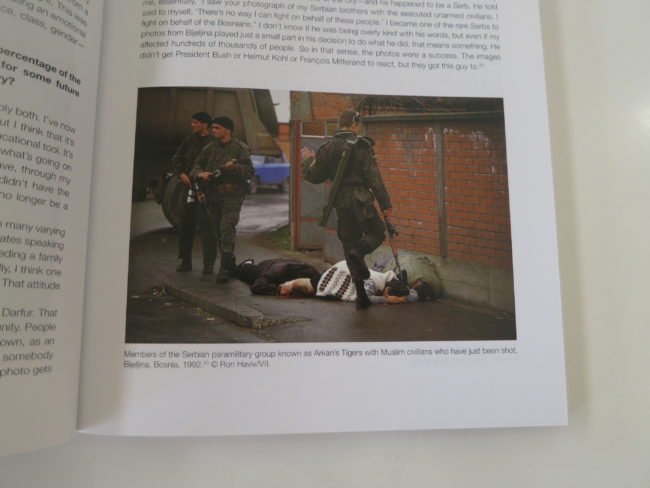

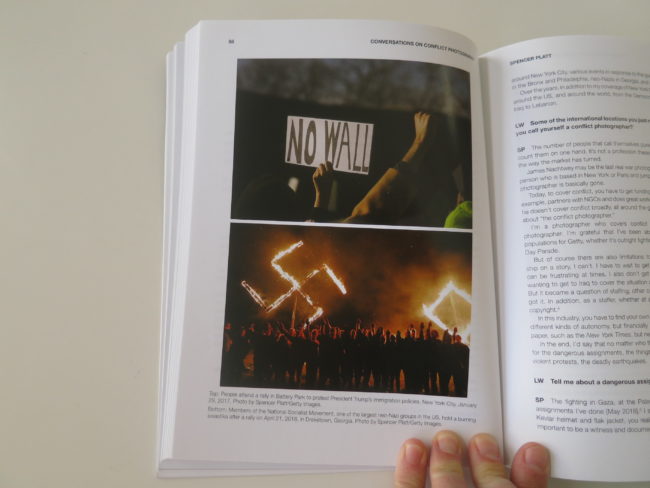

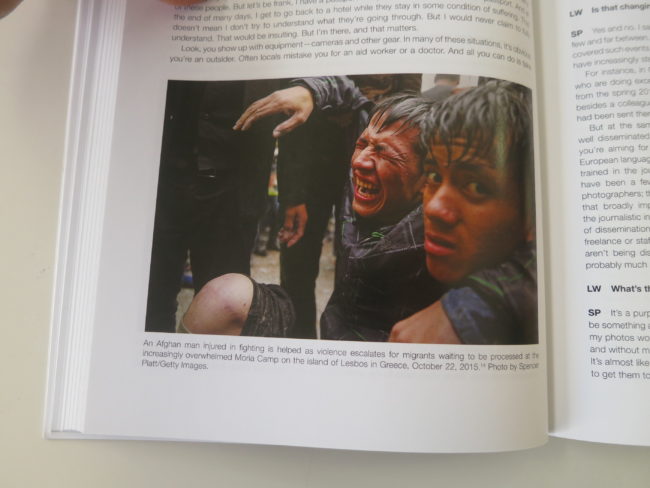

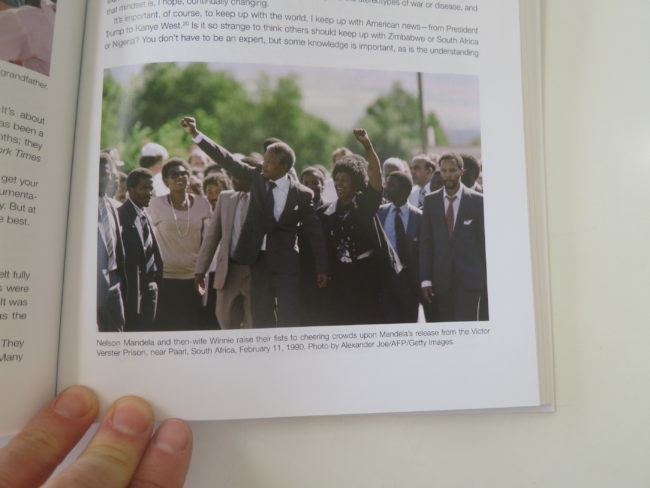

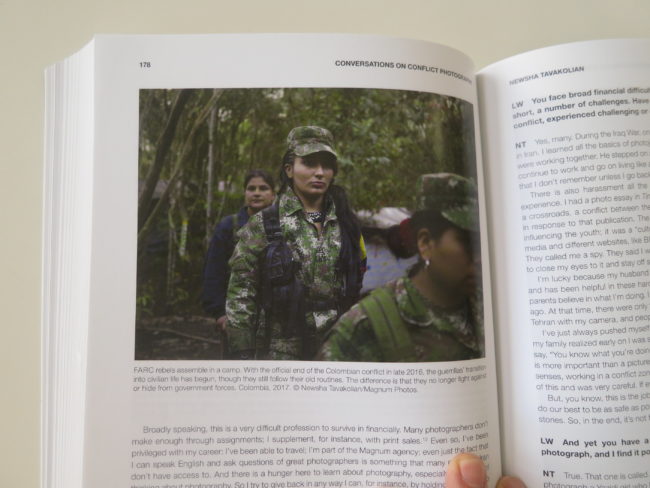

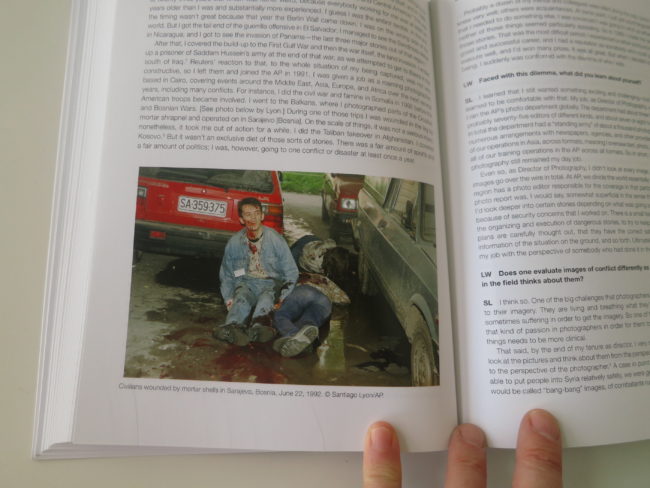

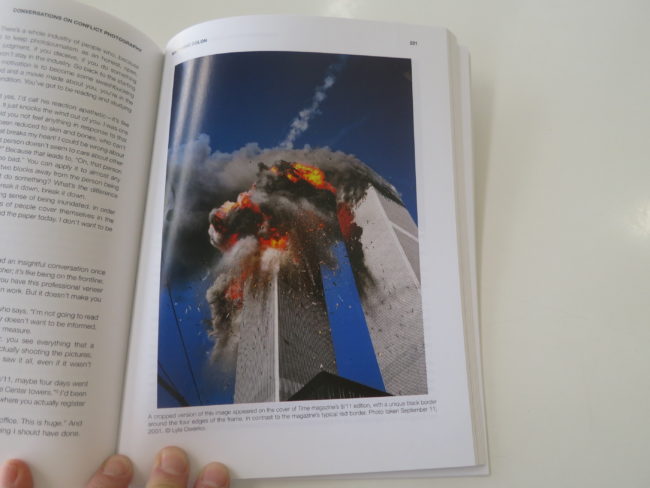

It’s crammed full of famous pictures, like Eddie Adams shot from Vietnam, the burning Twin Towers from Time Magazine, or Nina Berman’s Marine Wedding photo. (Which we showed here in 2011.)

I just needed to realize that because I’d read and written about these things before, that didn’t meant it wasn’t newsworthy or beneficial for many of you now, in 2020.

Given the subject matter, there will be a lot of photos of violence below. (Or its remnants.)

Be forewarned.

But just as I can reconsider whether a book is worthy of review, I can also wrap up quickly, and let the photos do the talking.

I think we all believe this kind of photography has a social value, bearing witness to suffering, for posterity.

But it also allows us to understand geo-politics on a local, human level.

Kudos for the job well done.

Bottom Line: Fascinating, dense resource book on conflict photography

To Purchase “Conversations on Conflict Photography” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me directly at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are interested in presenting books from as wide a range of perspectives as possible.

1 Comment

“But they’re not going to change anything!” True. The time when conflict photographs helped change public opinion in any drastic, meaningful manner has been long gone since “Napalm Girl” and the My Lai Massacre. We currently live amidst a mind numbing glut of imagery.

And yet, these photographs, these books, these testaments serve as important reminders of what occurred despite us, and because of us; just as impeaching a POTUS was important despite the outcome, because some among us have to say that we notice, we care- and that if the perpetrators are allowed to go about unpunished and unscathed, it wasn’t because we were ignorant of the facts, but because we allowed, condoned or ignored it…

Comments are closed for this article!