The New Yorker

Director of Photography: Joanna Milter

Art Director: Nicholas Blechman

Photo Editor: Thea Traff

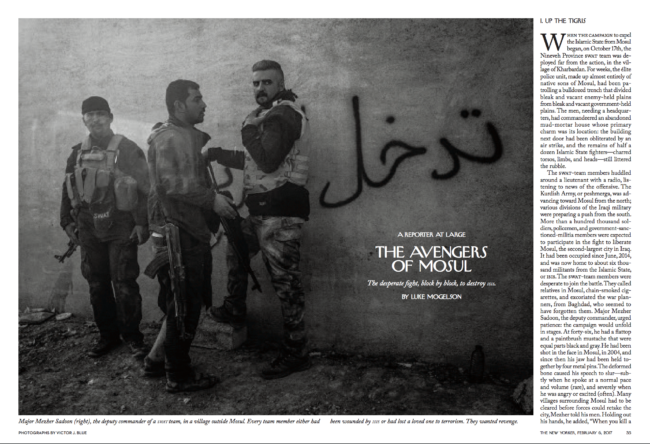

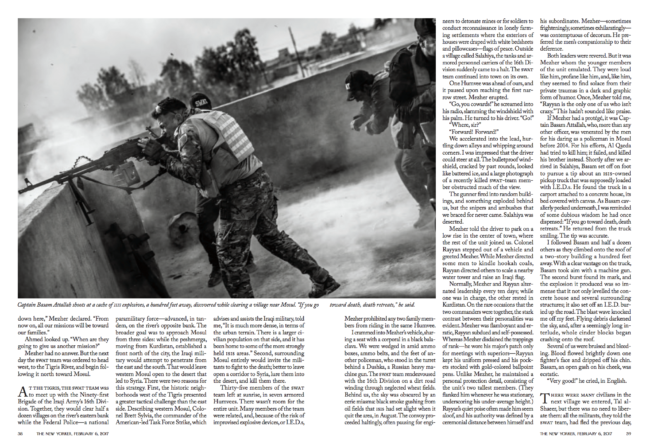

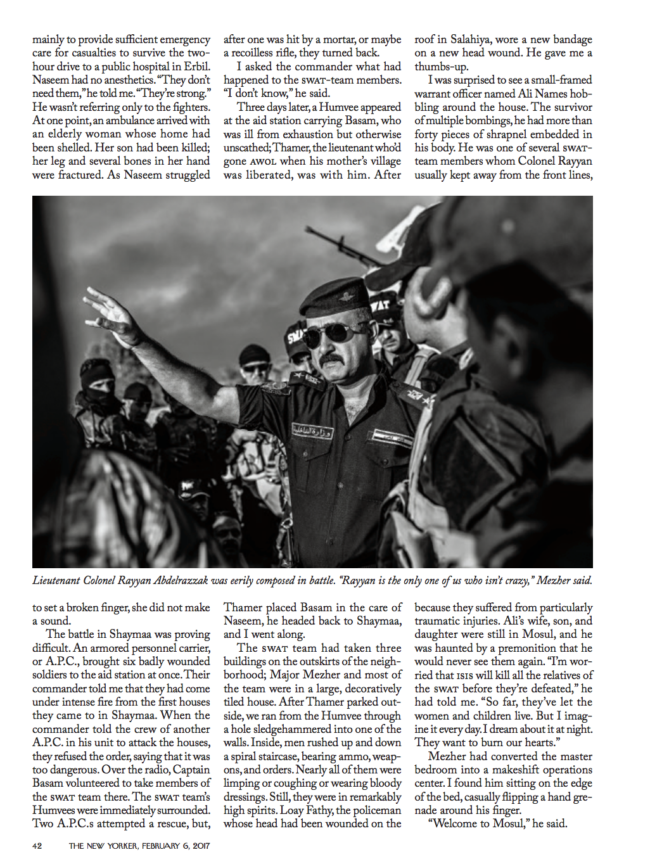

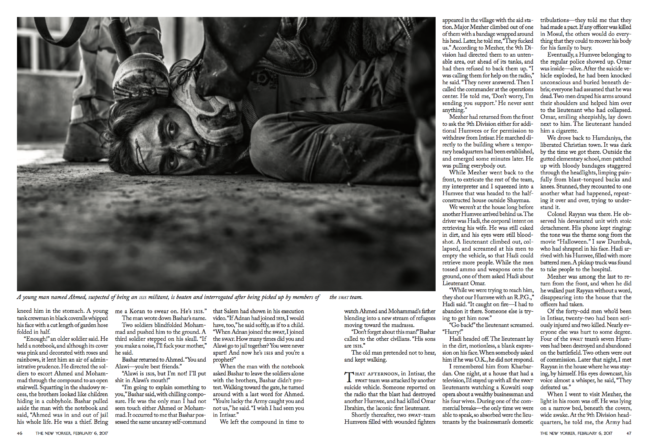

Photographer: Victor J. Blue for The New Yorker

Full story here

Photo Booth feature with Victor here

Heidi: How long were you on assignment for this story?

Victor: We worked on the piece for 6 weeks.

What was the hardest aspect of this assignment?

As with any military operation, there was a lot of “hurry up and wait.” It was tough to stay sharp and keep shooting when the down time dragged on, and to balance it with the more dynamic times.

Did you learn anything new about yourself for this project?

I learned that I need to trust a little bit more, and I need to count on my second and third impressions of people and situations as much as my first one. A few times, guys that I thought weren’t really into our presence ended up being some of the ones I eventually connected to the most.

Did you have any protection?

Well, we had body armor and helmets. But we did not work with a security advisor or anything like that. It was just me, Luke Mogelson the writer, and our buddy Sardar, our fixer and translator. We looked out for each other.

How many languages do you speak?

I speak English and Spanish. The Spanish didn’t help me out much on this one.

For each published image how many frames were shot in that scenario?

That’s really hard to say. It just depends. Sometimes only a few, sometimes hundreds. I can say that we ended up publishing like 22 photos total, and I ended up with about 300 selects.

You have a gift for being accepted into closed/difficult communities, how do you earn their trust?

I just try to be really open with people, and easygoing. I try not to be a “bro” or fake about who I am or what I’m doing there. Folks usually seem to relate to that and while it doesn’t ingratiate you off the bat, it earns trust over time.

What coping skills to you use to deal with the intensity of the work you do?

When I’m working I write quite a lot, and I think that helps. When I get home, one of the hardest things for me is not wanting to let the experience go- to not slip back into my spoiled first world existence. But that happens and I guess that’s natural. I make a concerted effort to reconnect with my friends and loved ones. I usually get sad sometimes, and I try to pour that into the editing of the pictures.

This is your life’s work, what cues do you now have that tell you it’s not the right moment to take a photograph or the situation is too intense?

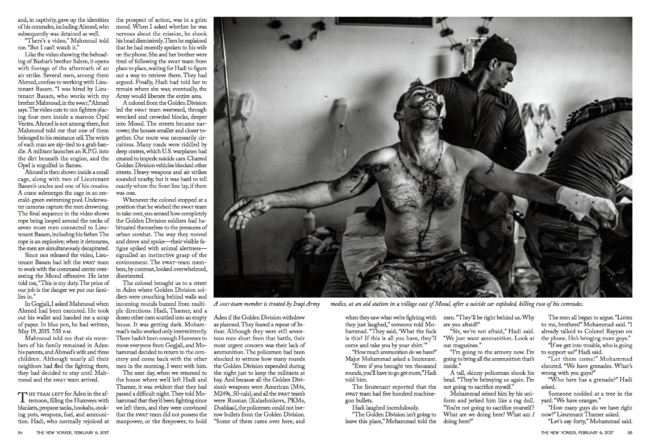

There was a moment that happened like the second day- one of the SWAT members came tearing into the base collapsing and crying- he had just found out his wife and children had been taken by ISIS. It was a really intense moment and we had just shown up. I was torn about what to do, but I hung back and didn’t really make a picture. I was betting that taking it slow with these guys, earning their trust before I jump in their face like that would pay off, and it did. Later, when things were way crazier, no one ever got mad at me making pictures. You just have to take it slow, figure it out, and be smart as well as brave about raising your camera when things get intense.

You are documenting some horrific situations, how do you cope with this form of photography while you are doing it? and after

I just try hard to concentrate on the pictures, on understanding what’s going on, and making powerful images of that. It’s my job to take pictures of very serious circumstances. If I couldn’t cope with it, that would be fine, but it would be irresponsible for me to go there to do it. Then I ought to be shooting other types of stories. That’s what makes us professionals- our ability to function in what are difficult, fluid, and at times dangerous scenarios.

Have you ever self-edited feeling that an image was too much to share?

I’m not sure I believe that anything is too intense to photograph. It’s my job to interpret something horrific and make a picture of it that people can look at. I don’t think I pull too many punches. Of course sometimes the circumstances around making pictures require me to think about what’s going on- I have to be careful to be an honest witness and not work as a propaganda arm for anyone. If I feel like folks are trying very hard to manipulate the pictures I am making, I am wary about publishing them. But that was never an issue on this story.

When people look at your work are you hoping they see composition and balance in some of the photos along with your message?

For sure! I am trying to make visually dynamic photographs. My goal is a set of pictures that both inform people intellectually and move them emotionally. If the pictures are poorly made, if I’m not working really hard to “see” them, then I am not doing my job. They have to arrest you visually, make you stop and feel something, then want to know something about the people and the circumstances they depict.

Do you find beauty in cataclysmic images? Just because something is terrible doesn’t mean it can share something wonderful.

It’s an interesting question. Beauty per se isn’t a goal I’m concerned with personally. To me there are much more important aspirations for my pictures- truth being the first. Like I said, I am trying to make the most visually powerful pictures I can- but I believe in photojournalism and I am consciously working within its conventions. I work hard to be creative, but I am not making art. Wars, social crises, marginalized people- I don’t see these as legitimate vehicles for my artistic aspirations. I believe that making well-observed documentary pictures of their experience is how I can best serve as a bridge between them and the moral imagination of the readers that will see the pictures.

3 Comments

Great interview. Great article. Great writing. Great photographs. Big respect for all concerned.

Couldn’t agree more. Crazy to go into that kind of situation and not only survive but leave with such impactful work.

Wow, those images leave me speechless. Beauty might not be the intention, but the humanity jumping out at me is its own kind of beauty. And I agree with the above comment about the interview–it was fascinating to hear about the process of bonding with the group. Victor is an incredibly brave photographer.

Comments are closed for this article!