I’ve been doing this a long time, as the column will be 5 years in September. In that time, I’ve seen books from every continent on Earth, two times over. (Yes, there were two books from Antarctica.)

The experience has increased my understanding of the world immeasurably. I am definitely a smarter, more empathetic person than I was when Rob first suggested I review books here at APE.

But until today, I’ve never cried before, when flipping through the pages.

Not even once.

Today, however, I wept.

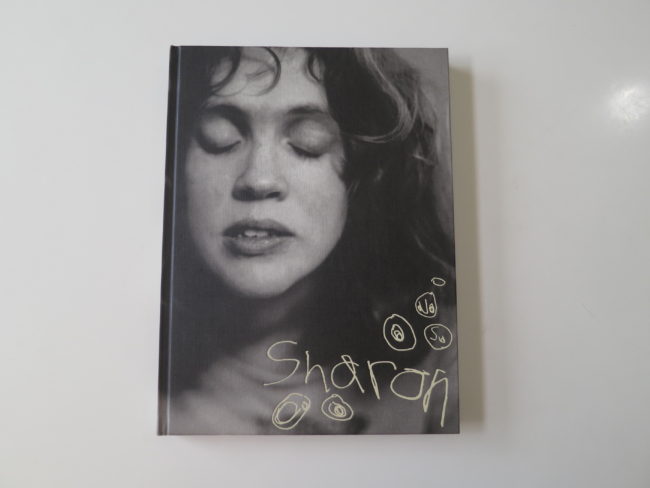

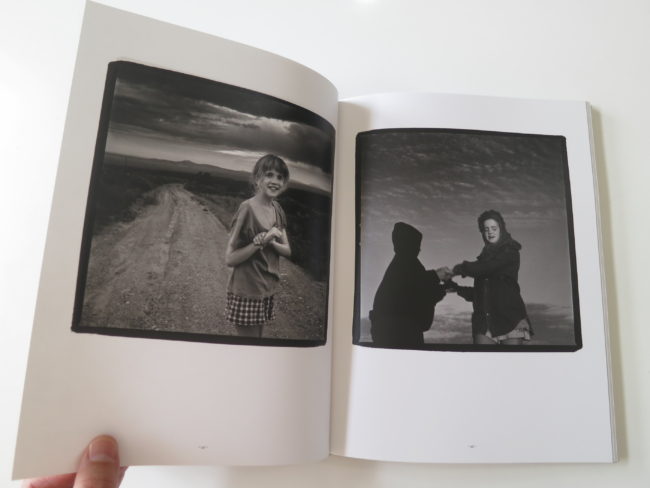

I was looking at “Sharon,” a new book by Leon Borensztein, recently published by Keher Verlag in Germany. This is as personal a book as I’ve seen, though others have risen to this level of honesty.

So why this book? Why now?

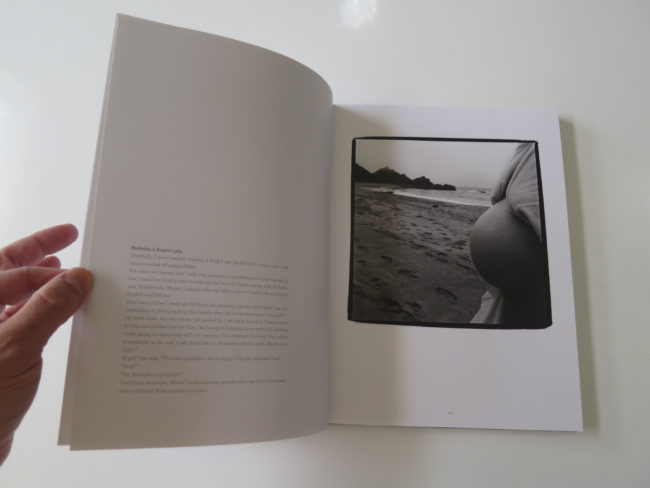

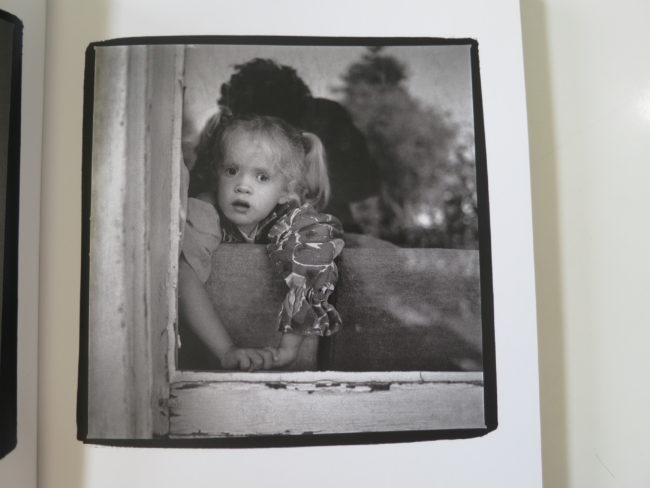

Well, “Sharon” is a photographic and diaristic account, by Leon Borensztein, of the 1984 birth, and subsequent life, of his daughter Sharon. Though her eyes are closed on the cover, and the text is scribbly, I had no idea what was in store, when I took the book out of its packaging. (This one was sent in a couple of months ago, and landed in the submission pile.)

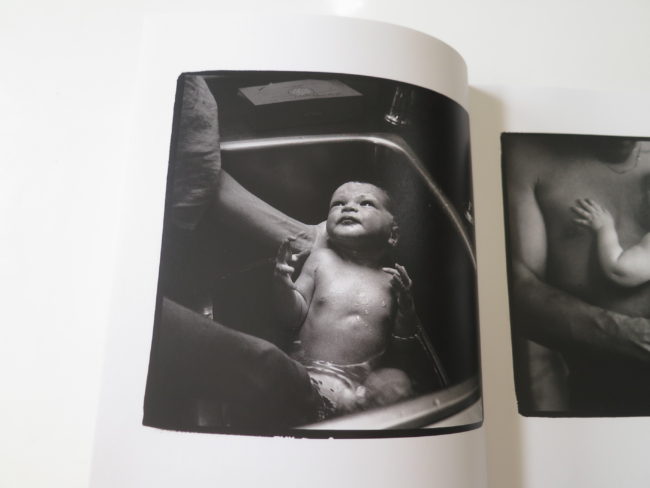

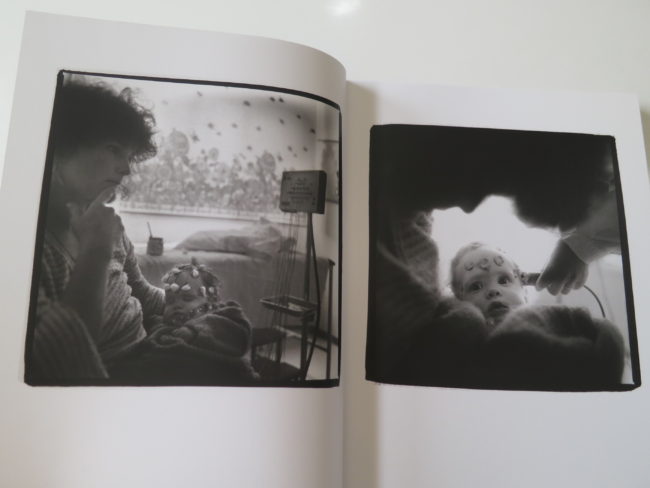

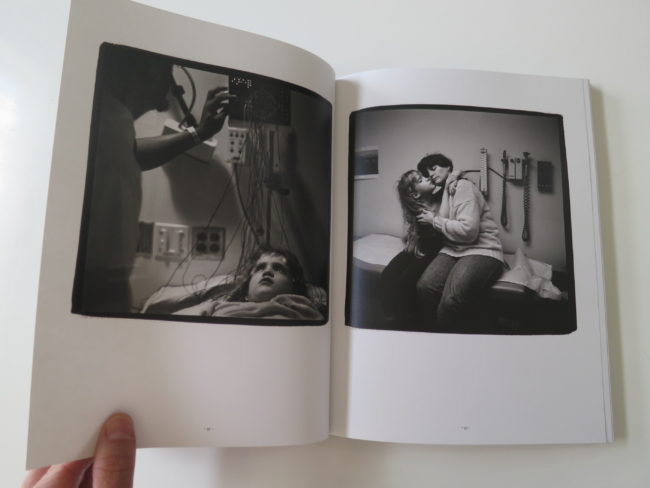

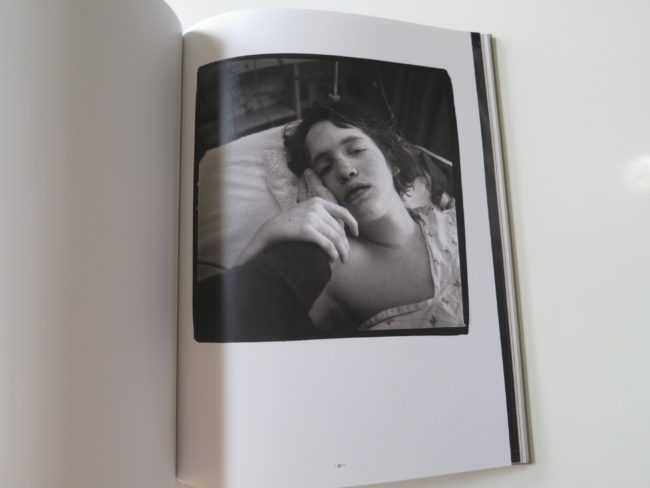

Within the first few pictures, we realize something is wrong. Baby Sharon has electrodes on her head, and that can’t possibly be good, right? (It isn’t.)

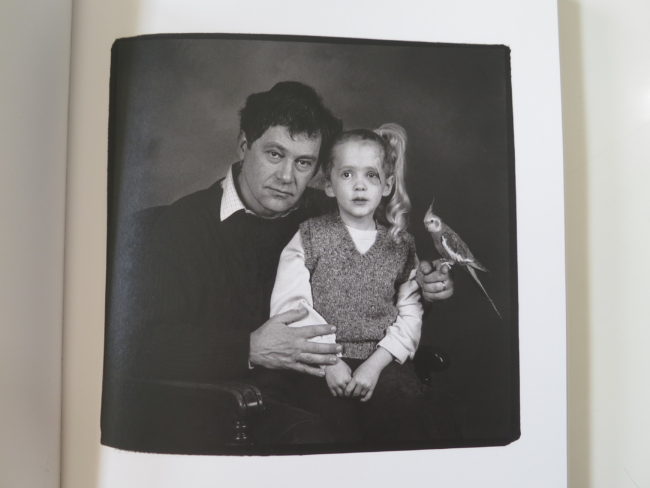

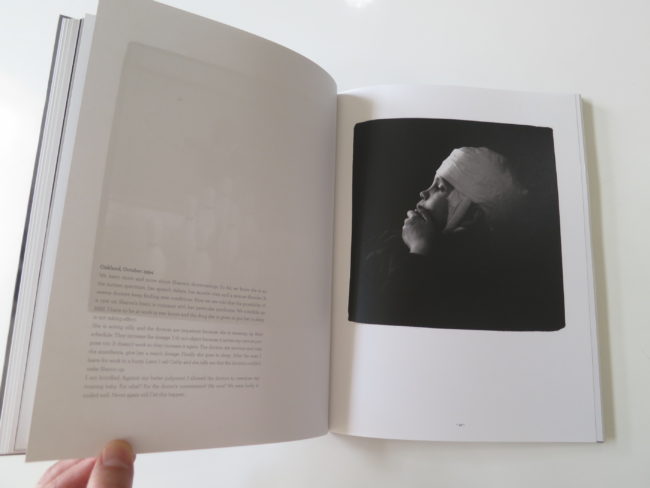

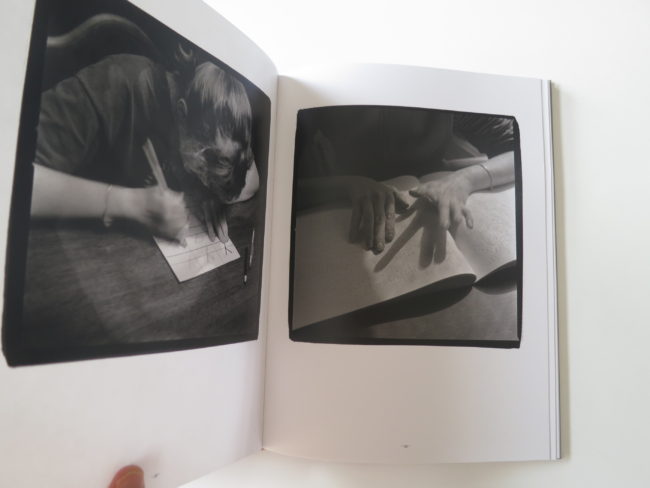

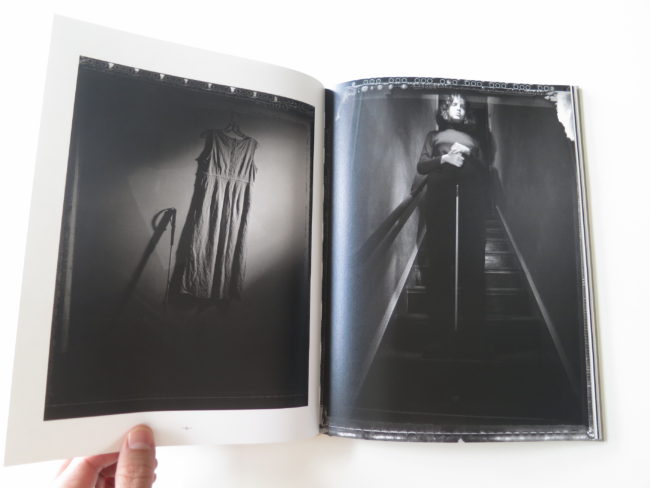

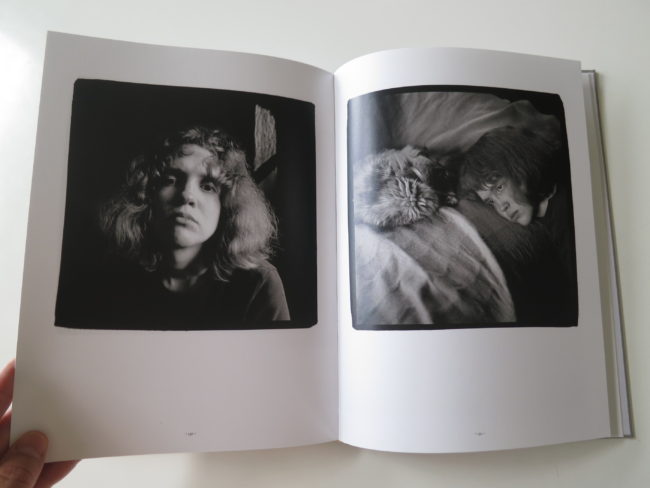

The pacing, and the balance between imagery and text, always feel right. The pictures are universally square, well-made, and shot in black and white, but they’re not GENIUS. Thankfully, they don’t have to be.

It turns out that Sharon has physical, developmental, and mental health issues, including being mostly blind. It is clearly every parent’s nightmare, and one I fretted about through the entirety of my wife’s two pregnancies.

What happens if you have a baby, so many of us fear, and it all goes wrong?

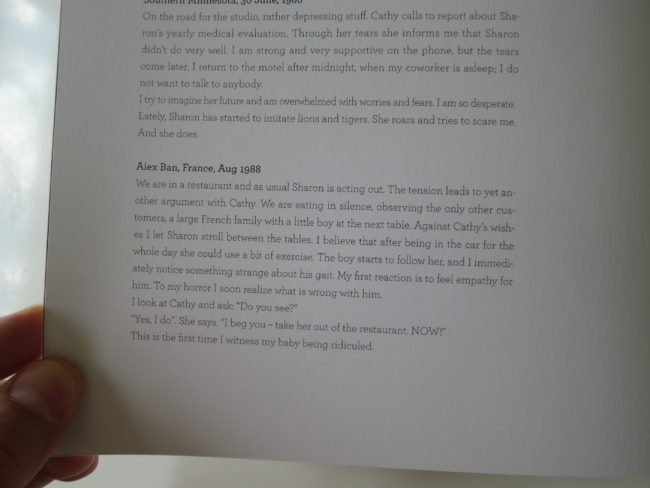

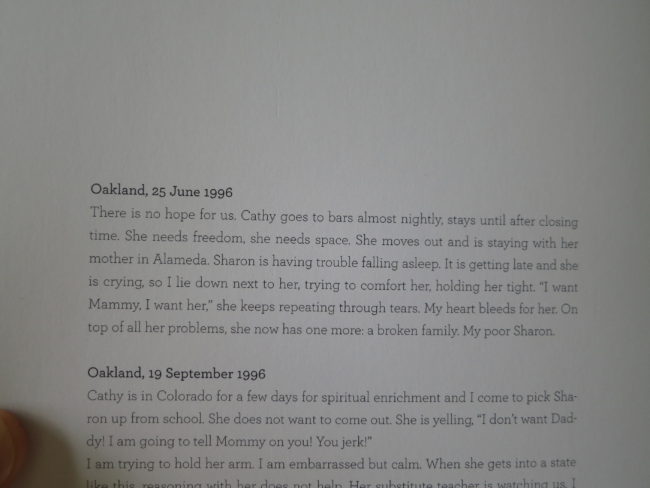

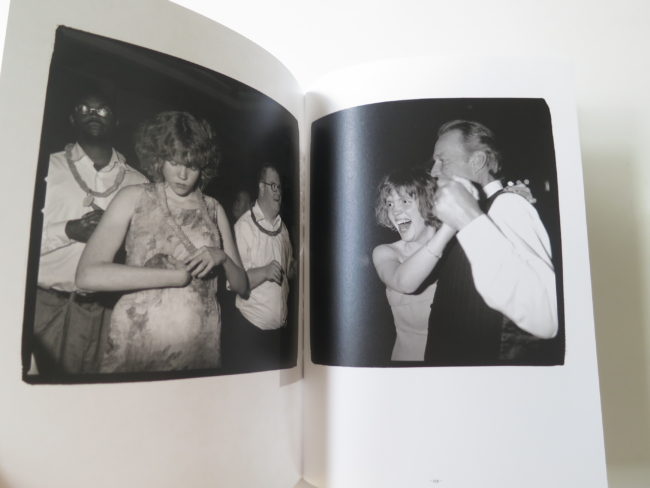

29 years of Sharon’s life are documented here, and the diary text openly shares how difficult it is. How draining. How depressing.

To make matters worse, (as is often the case in relationships enmeshed in trauma,) Leon splits with his wife, and ends up becoming Sharon’s sole caretaker. His ex-wife is eventually busted for meth, suggesting she was unfit as a mother.

Wow, is this a heavy book. But it is also beautiful, because as Pixar teaches us in “Inside Out,” sadness is a valid part of life. Sometimes, it’s the only sane reaction to life’s unfairness.

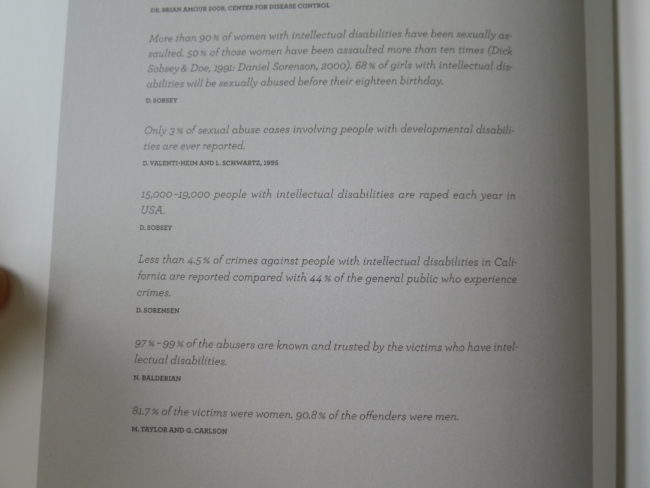

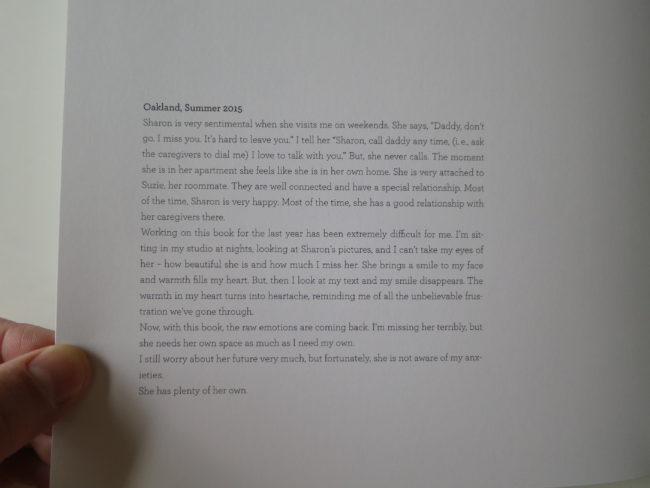

In the end, Leon decides to place Sharon in a facility, after spending years trying to find the right one. He is well-aware, and presents to us, the statistics facing disabled women, with sexual abuse rates that are heart-breaking.

According to the last text in the book, it was a good move for father and daughter, as both were able to move on with life, while remaining extremely close. It’s just… So. Fucking. Poignant.

In life, I’ve found, sometimes the small coincidences keep piling up to the point where it makes sense to listen. I thought I was done with my little San Francisco series, but it turns out that some of the people about whom I’ve written in the last month were big supporters of this project.

Who knew?

And just this morning, I was engaged in a Twitter conversation with people about the over-saturation of the photo-book market. (Precipitated by a Tweet from NYT critic Wesley Morris, who lamented the closing of Powerhouse Books.)

I told a couple of Twitter strangers that with so many books on the market now, as near-every photographer makes a book for each project, it was of course impossible for them all to sell well. The supply has increased exponentially; not so the demand.

The responses to my Tweet were ironic, accusing me of quashing dreams. Not so, I replied.

Make a book.

Have at it.

Go nuts.

Just this morning, mere hours before I picked up “Sharon,” I told people there were other reasons to make a book, beyond financial remuneration.

Books are tangible. They provide closure. Deadlines push people to finish, to grapple, to face the work they’ve made, and then perhaps let go.

It wouldn’t surprise me if this book sold well. It’s an excellent publication. But somethings tells me it’s already a massive success for the artist, because it’s shined some serious light on the dark recesses of his life.

Life is beautiful, according to Roberto Benigni, but it is also rather tragic. Capturing both realities in one book is an achievement. If it can make me cry, for goodness sake, you might want to check this one out.

Bottom Line: Powerful, diaristic account of raising a disabled child

1 Comment

Have always loved his portraiture; insightful, yet distanced. This, of course, takes us well beyond his artistry and brings us into the very heart of what he is experiencing as: father, caretaker and human being.

Having worked both with adolescents with severe emotional disturbance and adults with developmental disabilities, I still can’t say I have any real hint as to what such a parent must endure. I have always had both the option and privilege to leave it behind when I go home. And I can only thank Mr. Borensztein for opening that window and letting us see…

Comments are closed for this article!