Wired

Associate Photo Editor/Editor: Jenna Garrett

Writer: Jakob Schiller

Read the online piece here

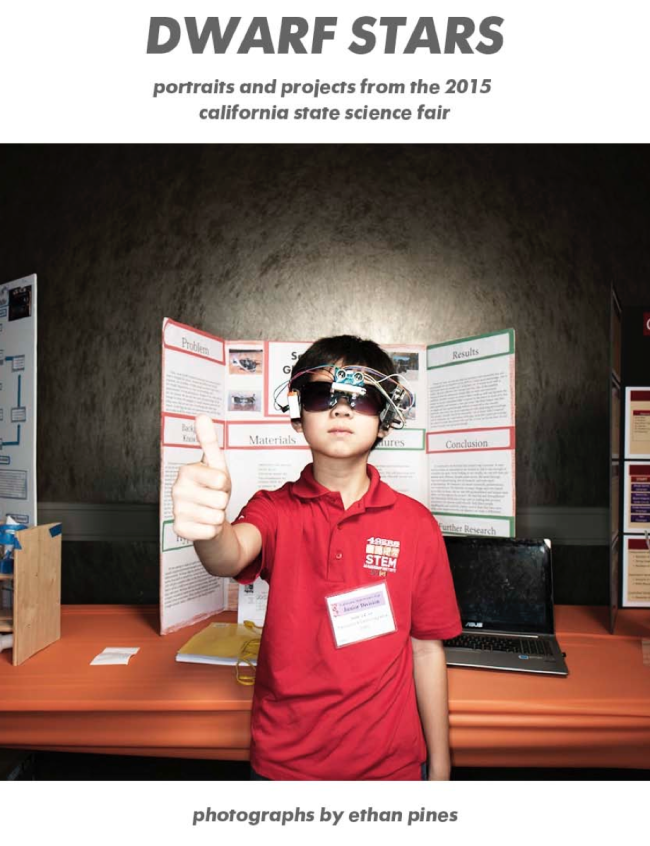

Photographer: Ethan Pines

Heidi: How did you find out about the Science Fair?

Ethan: A close friend of mine is one of the directors of judging, and every year he tells me that I need to come and shoot — that it’s full of quirky, imaginative kids with inventive projects and large personalities. And it’s never been covered well. This year I finally decided to do it.

What about the fair appealed to you? Had you seen an image/student that compelled you to take it on as a personal project?

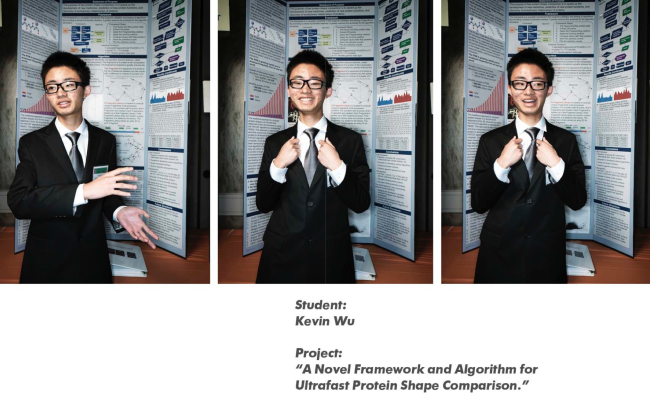

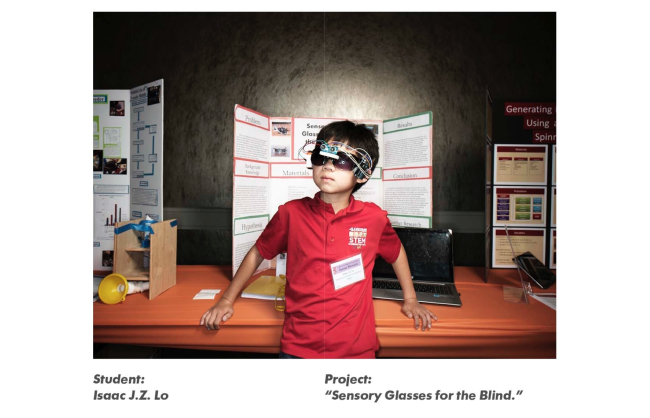

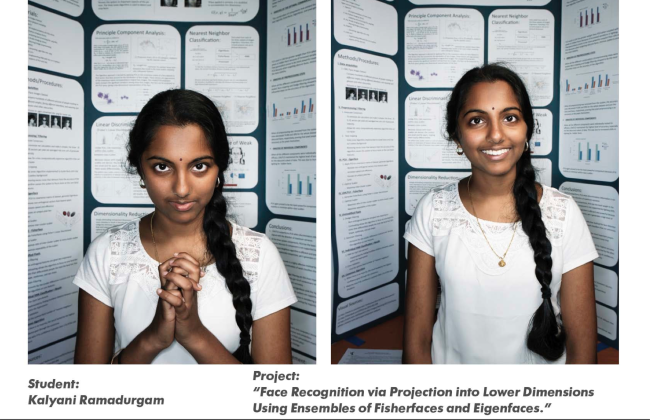

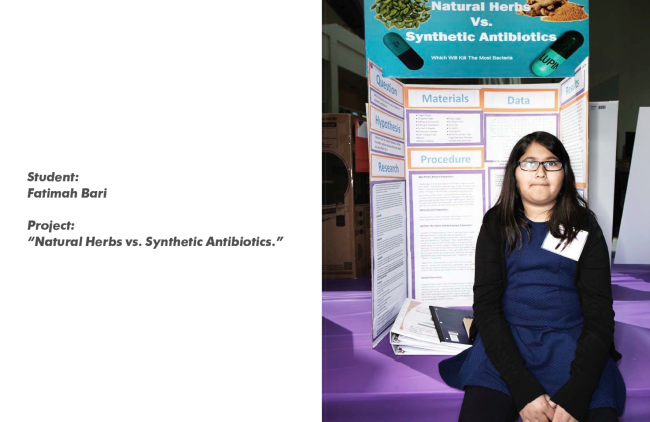

I’d seen a few snapshots on the Science Fair website from past years, but until I arrived at the Fair I hadn’t seen anything conveying the spirit of the kids, the uniqueness of their projects and the atmosphere of the day. And I think it’s all these elements that appealed to me. I was a bit of a geek as a kid, but I always wanted to be one of the cool kids. And I think that was a mistake. What I admire and love about the kids at the Science Fair is, they absolutely believe in themselves and their visions. They’re not there to win or to get famous, but because they’re proud of what they’ve done and are excited to show it off.

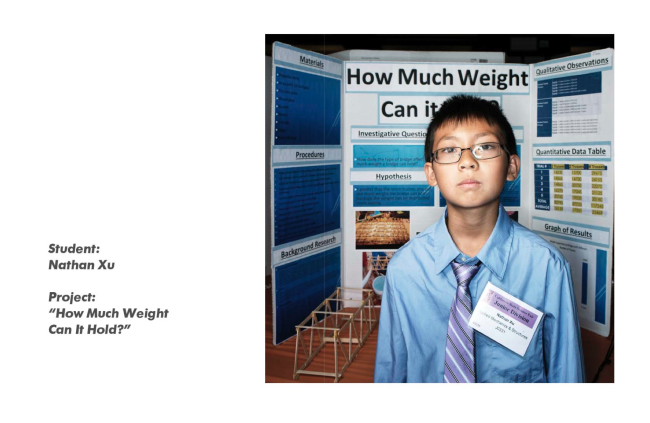

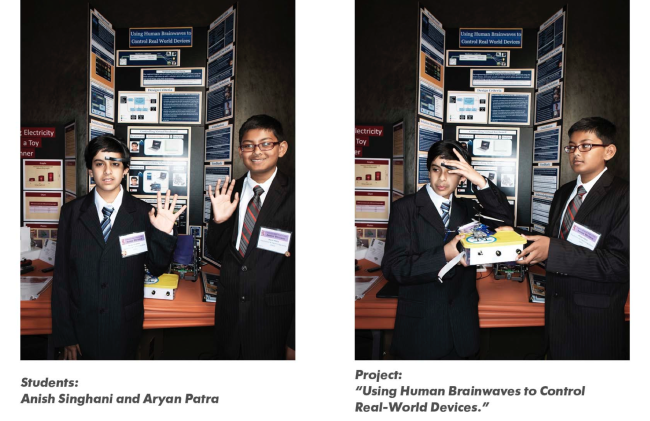

It’s also the kind of portrait series that, if you choose the right kids, almost can’t go wrong. It’s easy to focus on gear and lighting and technique, but photography is really about the subjects and the content, and it doesn’t get better than this. It was amazing — over 900 kids and projects, all of whom won regionally or locally to get here, all of whom converge on the California Science Center in downtown L.A. with their ill-fitting suits, their adolescent awkwardness, their earnest enthusiasm, their fairly mind-blowing projects.

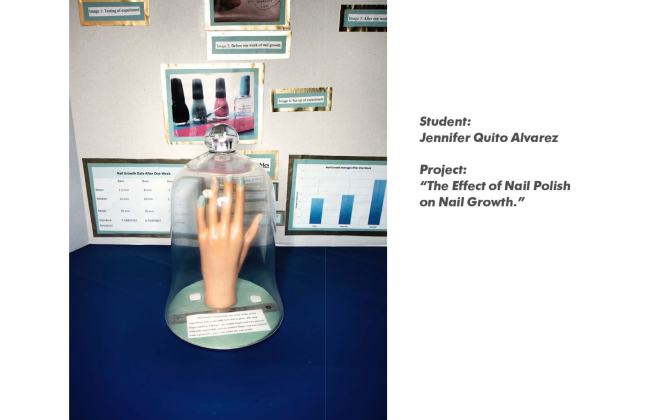

I’m also a longtime fan of science fiction, and ultimately that’s what many of these projects are — new ways of thinking about problems, imaginative forays into the future.

Did you set out to have it published? or was this purely a creative exercise for you?

I always hoped to publish it somewhere but didn’t get much interest beforehand. So I thought I’d go and shoot something good, then send it out afterwards. I wanted to make photo editors’ jobs as easy as possible — get something in front of them practically ready to go. The Science Center was also generous and trusting enough to give me a media pass and full access without a specific editorial assignment, so I wanted to make sure I did right by them. They and the Fair deserve the coverage.

What’s the difference between shooting this type of series and let’s say a client job? How does your creative process or mental process compare?

Of course I can do whatever I want with a personal series, as opposed to a client job with a specific creative mandate. But what I did is exactly what I would have done if a magazine had assigned me the shoot. If an advertising gig sent me to the Fair, there would have been a lot more discussion and preparation beforehand regarding the ultimate purpose and use of the images, the client’s and agency’s creative direction, the message we wanted to convey, what some of our ideal images might be, etc. And I would have put a lot of thought into how to direct the kids, how to dramatize the client’s goal and agency’s ideas, what moments I’d be looking for, what scenarios I’d want to create, and how to make all that happen. And of course how to light it, what gear I’d need, what crew, what preproduction, and so on.

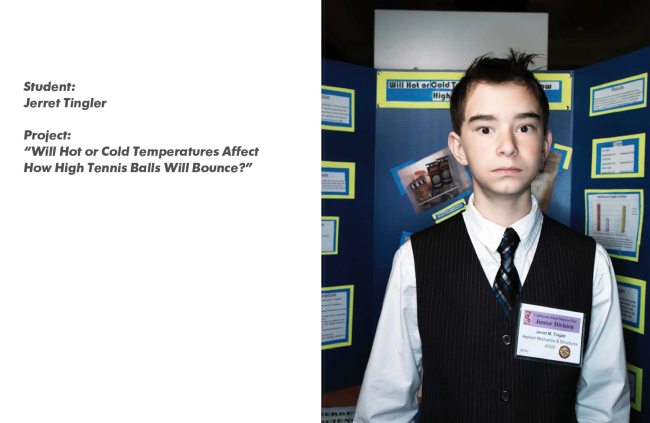

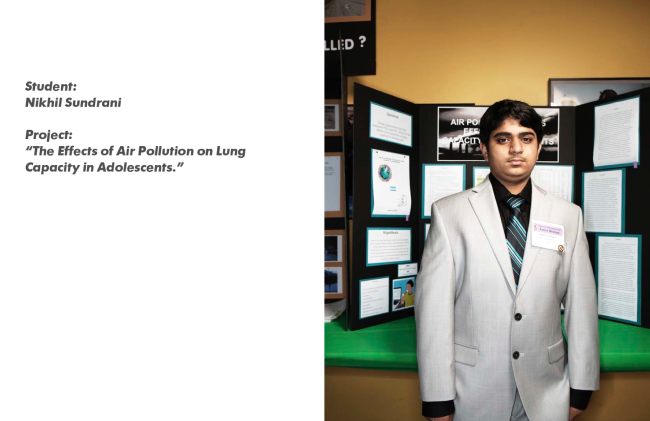

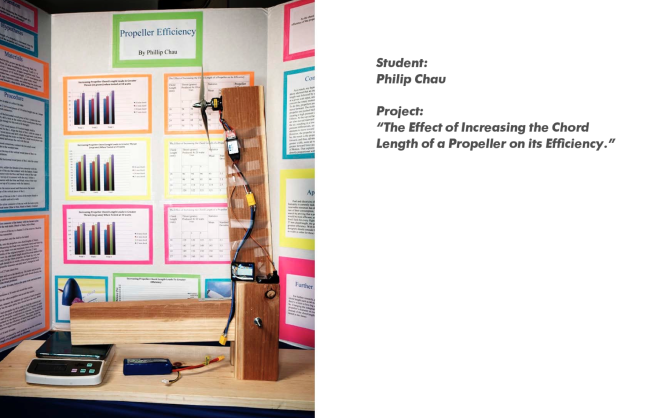

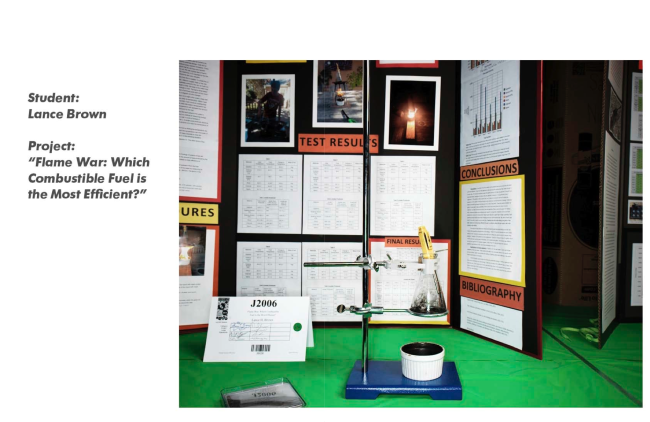

Since this was a personal series, my preproduction focused on how I wanted it to look, how to light it to get it there, and how to rig a battery-powered, portable strobe setup that my assistant and I could easily move around and manipulate in small areas. There was a lot of coordination beforehand with the Science Center, and I went the day before to scout. I also put some thought into creating a well-rounded photo essay — including details, still-lifes of projects, overviews of the exhibition rooms — rather than just a portrait series. As for directing and the content of the shots, I’ve shot so many portraits by now, I didn’t do much preparation beforehand. Between the kids themselves and the way I shoot, I felt I’d end up with what I was looking for. Too much preparation for something like this, and you can end up focused on a preconceived agenda rather than what’s happening in front of you.

How did you determine who would be shot/made the edit?

Determining whom to shoot was tough. Not because there weren’t enough good subjects, but because there were too many. Nearly 1,000 entrants and projects, and only a four-hour window when the kids are out with their projects for judging. Once we were inside I skimmed the aisles of one main area to find the first few interesting-looking kids with interesting-looking projects, After those, I did it again in the next area. Any one of those hundreds of kids could have been a complete gem to shoot; I just had to choose and run with it. And make it as good as possible once we were shooting.

What did you say to the kids to get them to open up? did anyone turn you down?

I’d simply stop at a kid, tell him/her I was shooting portraits, and ask if I could photograph him/her. It helped to have a media pass on my shirt and be the guy with the strobes flashing at various places around the Science Center. No one turned me down. Most of them seemed eager to share what they had worked on. And if they were a bit embarrassed, that also makes for a good portrait.

Once we were shooting, I watch for good moments, shoot the moments between the poses, talk with them, get them animated and expressive, work with whatever presents itself spontaneously, and make sure I get what I have in my head as well.

Once you saw the body of work, what were the key factors in choosing Wired over let’s say another tech publication?

Choosing Wired was a no-brainer. It’s the highest-profile and lushest tech publication out there. I think it’s one of the best-designed and -edited publications, period, tech or otherwise. I’ve shot for them before, so I thought that my pitch email would at least get read.

What did you pitch consist of? How many images, what was the crux of the text?

I edited down the shoot to a tight 21-image photo essay that I laid out in a .pdf with a title page and simple captions. I emailed it to Wired with a brief explanation of the Science Fair, and let the .pdf speak for itself. Once they accepted it, they asked me for a broader edit. I sent them everything that I’d be happy to see in print / online, and let them create the final series. Their version and mine ended up fairly close, so I felt that they understood the essence of the project.