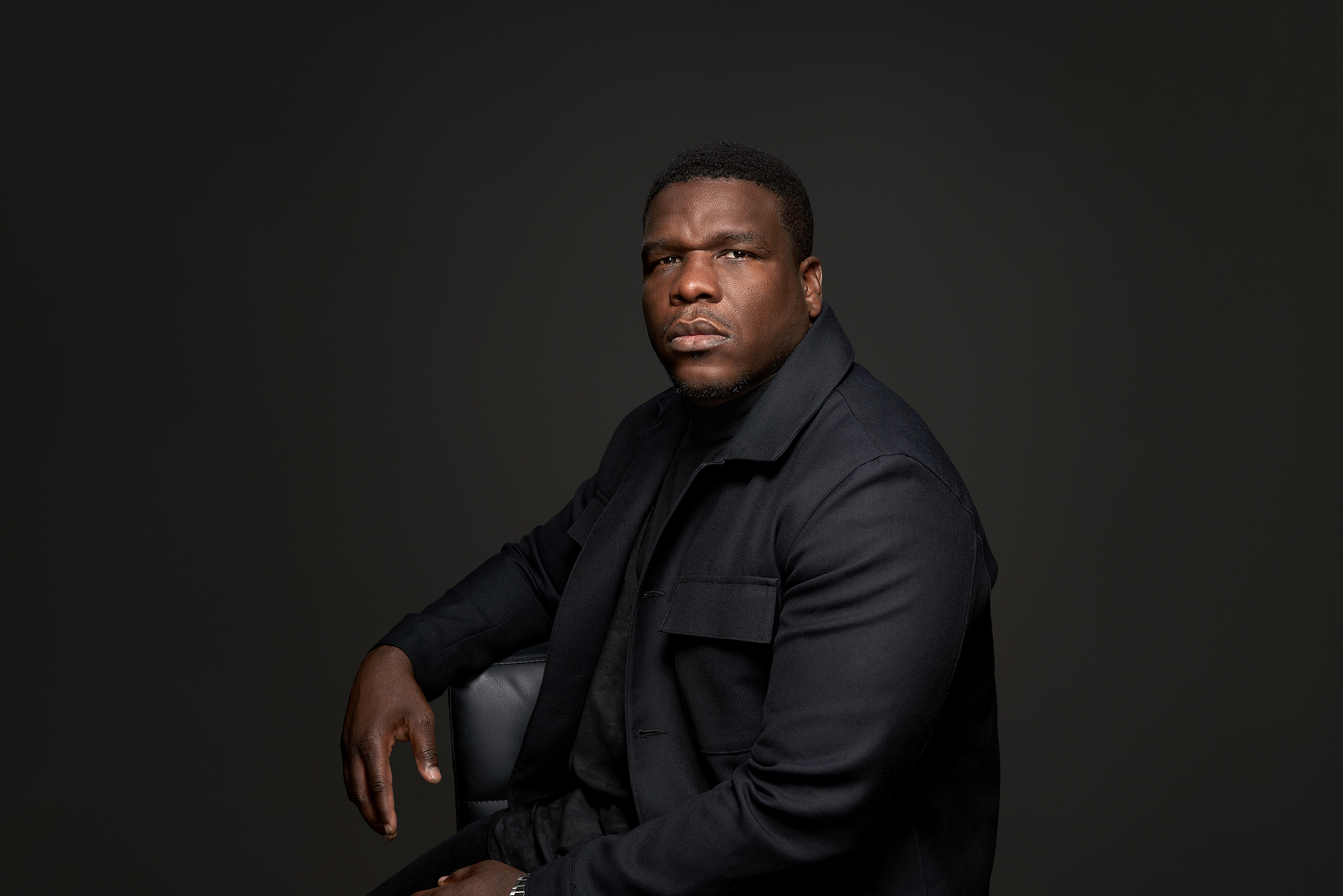

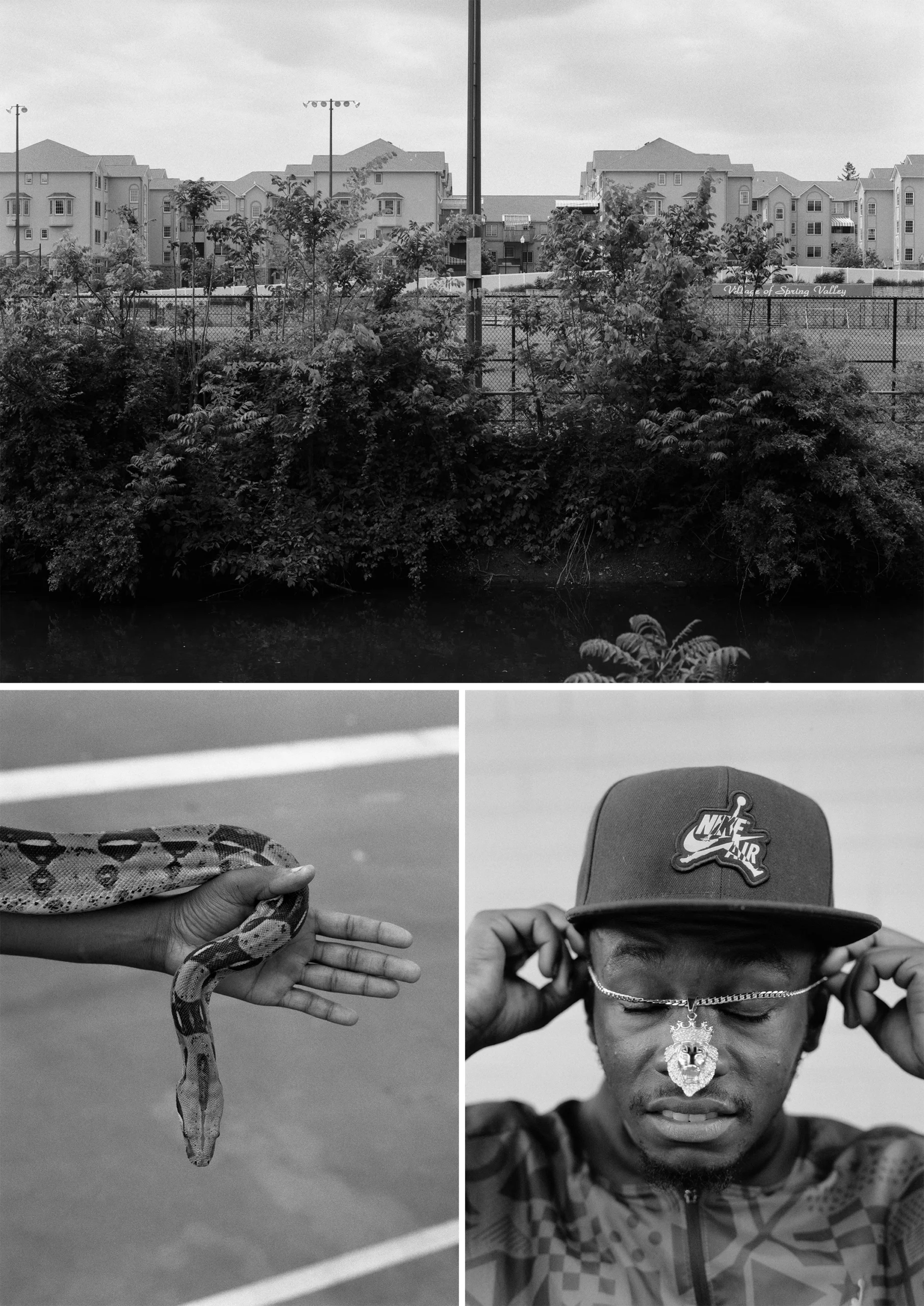

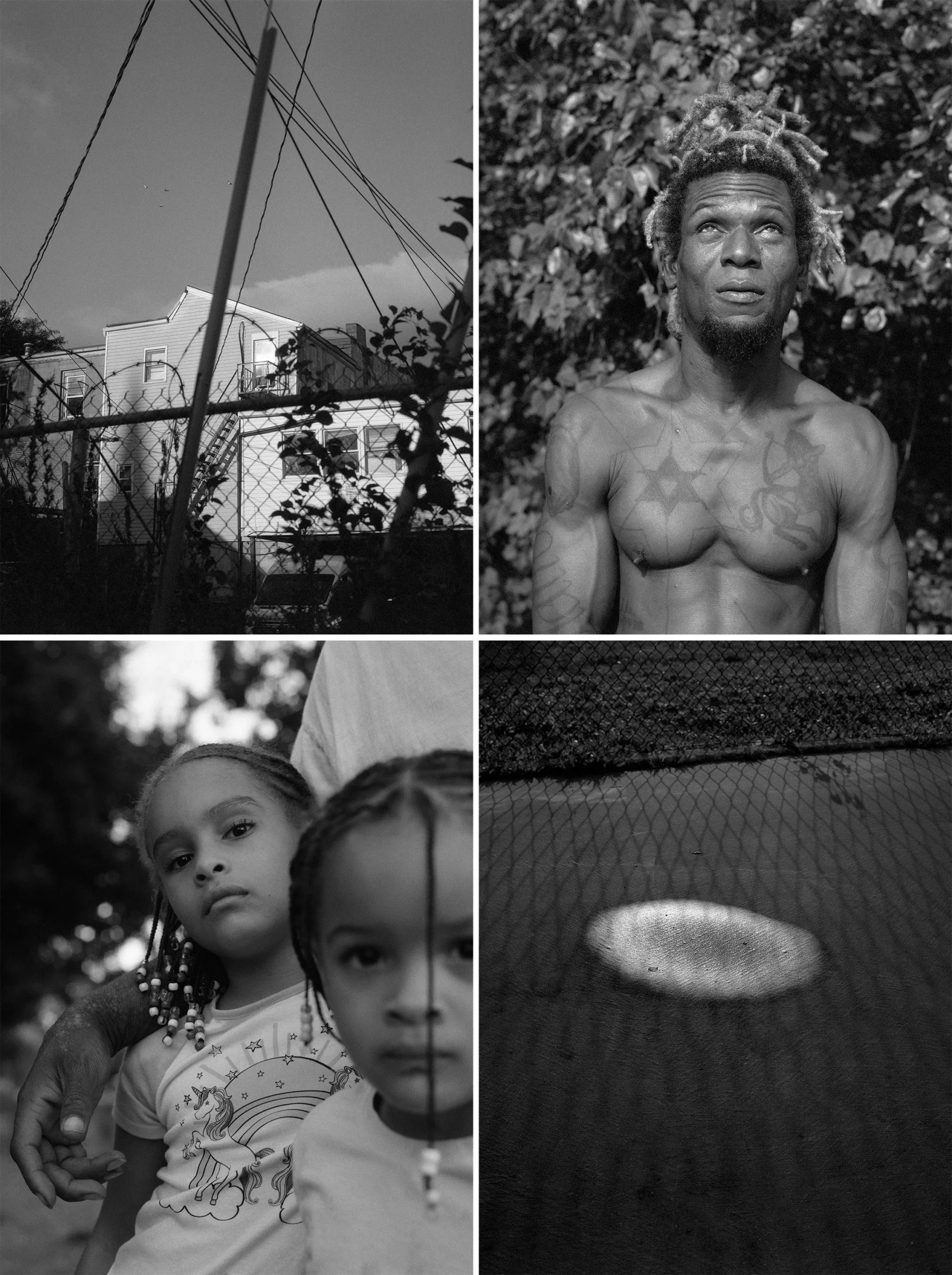

Photographer: Seth Beck

Heidi: You have been scanning the 1000+ slides for the past 10 years – what did you think when you first saw all the boxes of slides?

Seth: Honestly, I was ignorant of the scale of the task. I had only scanned slides in small batches before. In the end, the effort felt appropriate given the subject matter. It was a struggle, just like the hike, but it also came with a real feeling of accomplishment. That said, I will likely have someone else scan a hundred slides of my parent’s thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail in 1972.

What were your feelings about handling tangible slides?

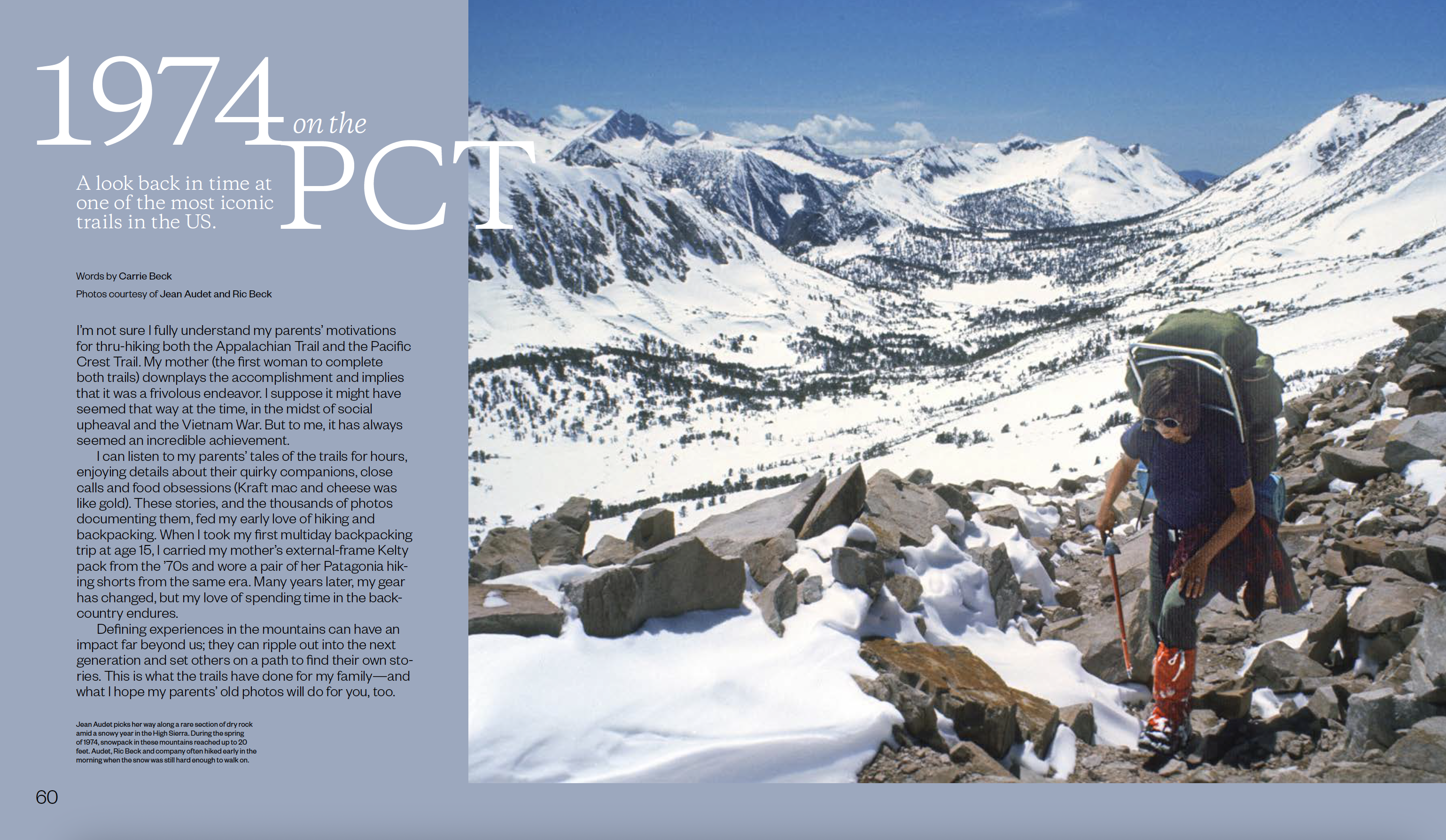

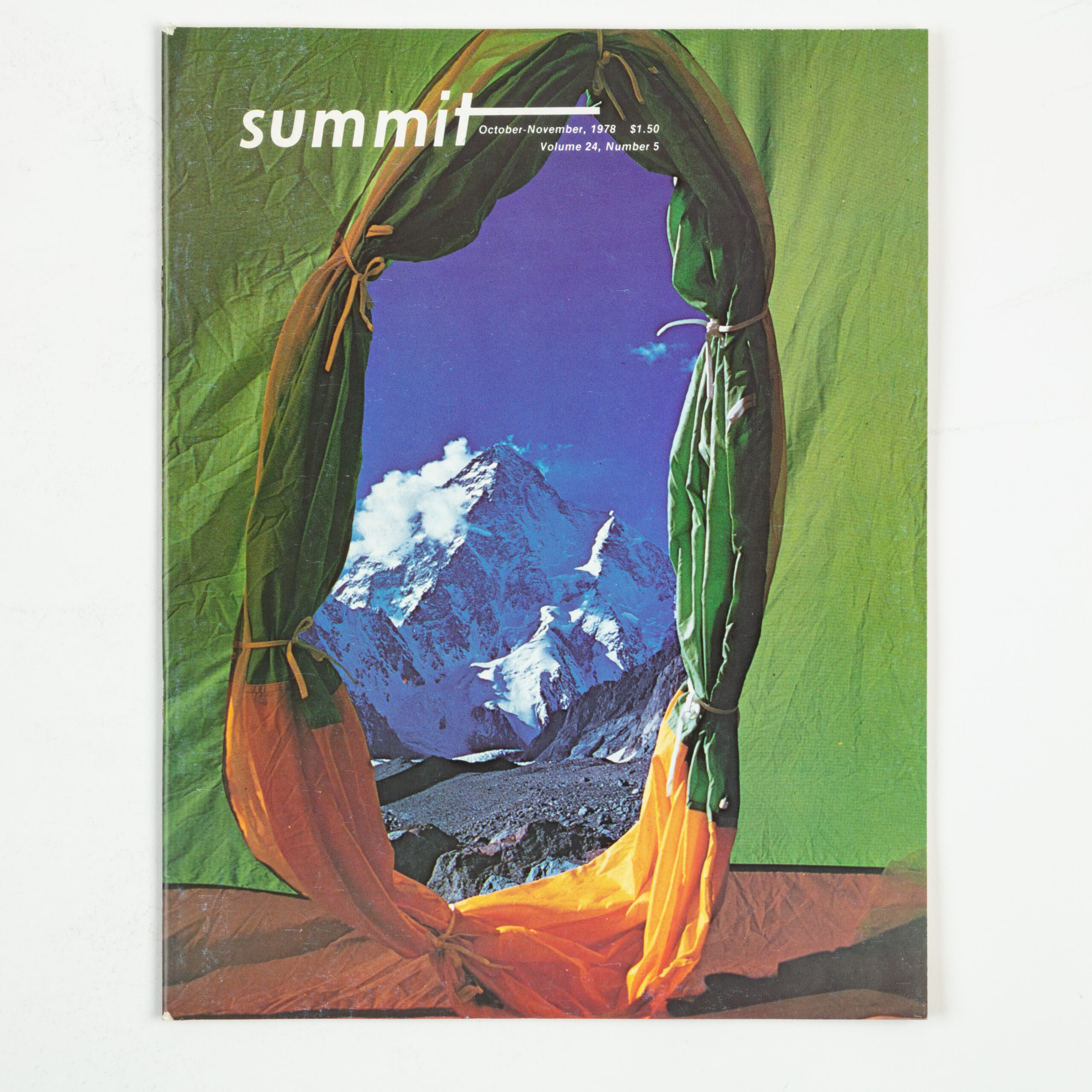

Some of my earliest memories are the slideshows my parents and friends would put on at Thanksgiving. These slides would transport me from our small farm in Vermont to wild adventures far away with crazy characters. They set the spark that would lead me on my path of adventure and exploration. That made the process of handling them that much more meaningful.

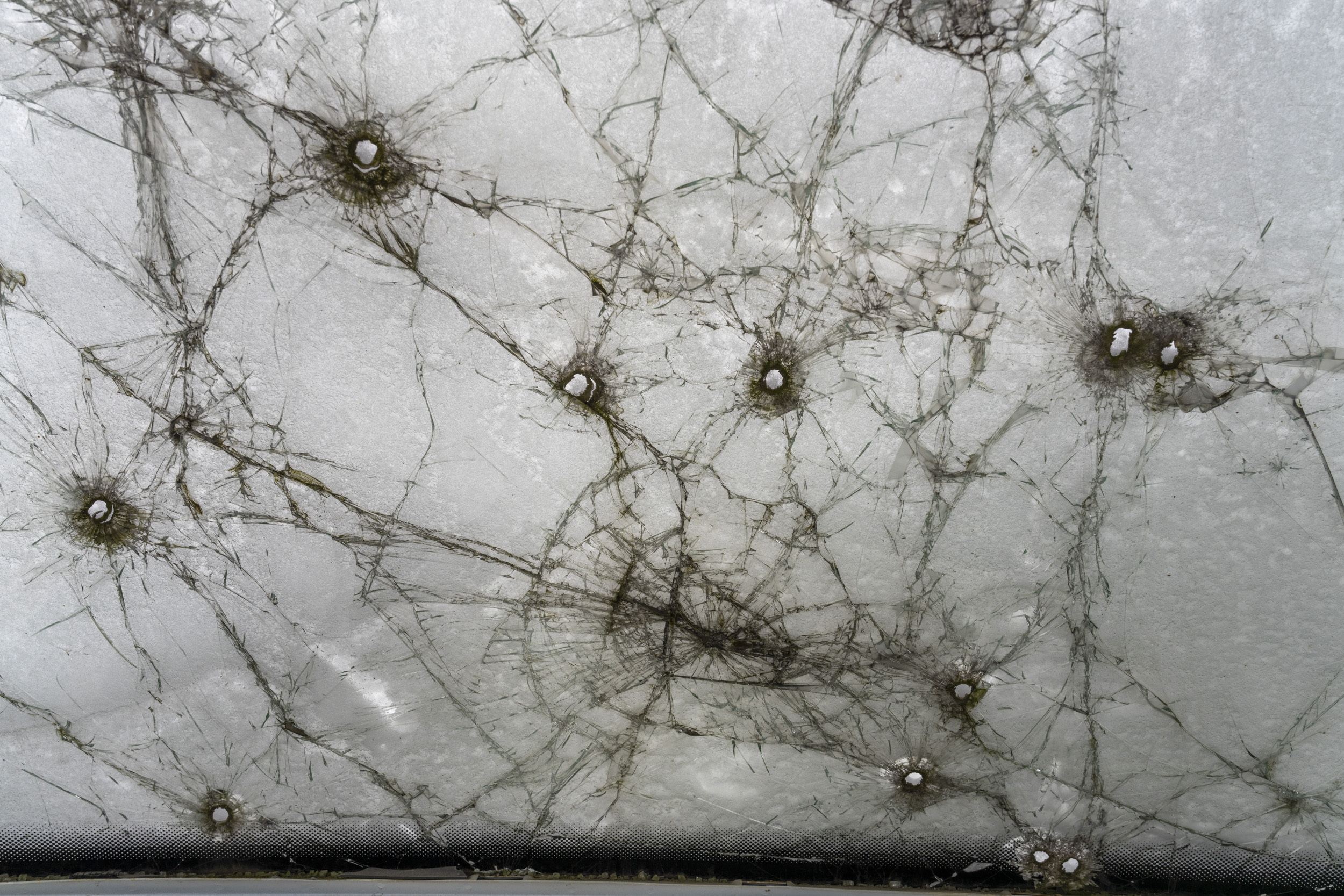

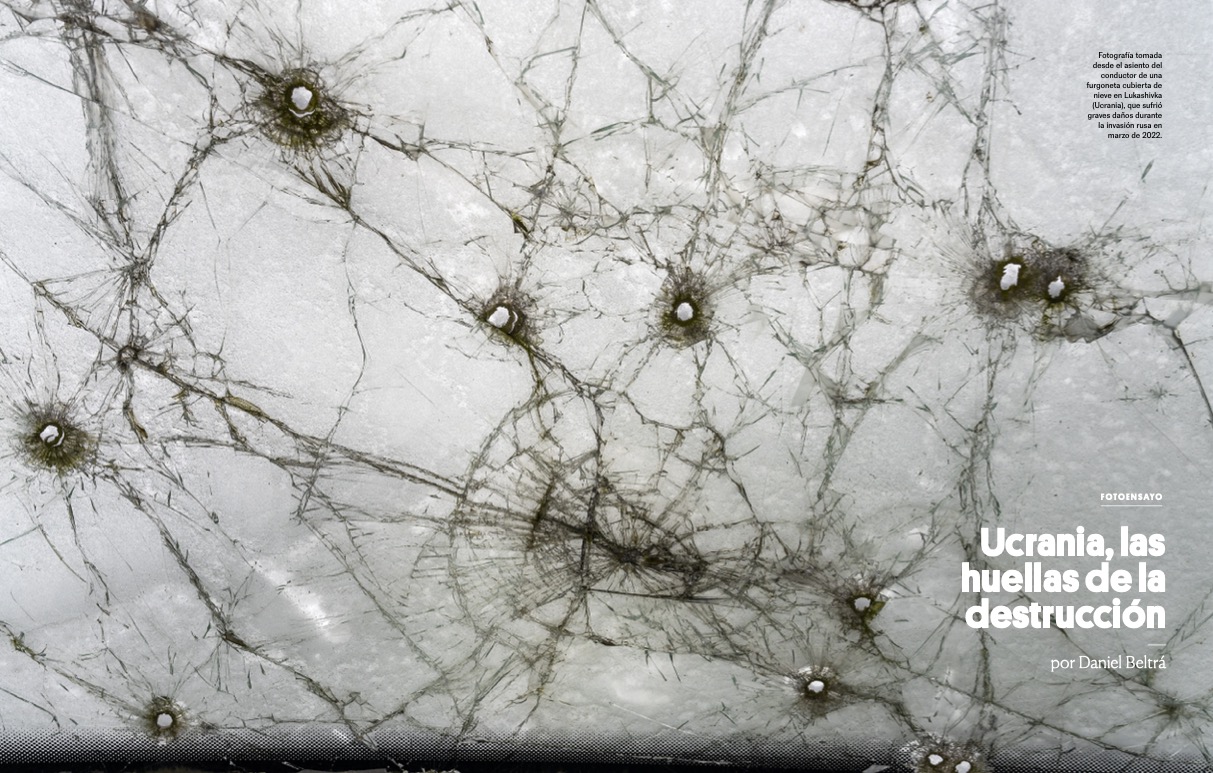

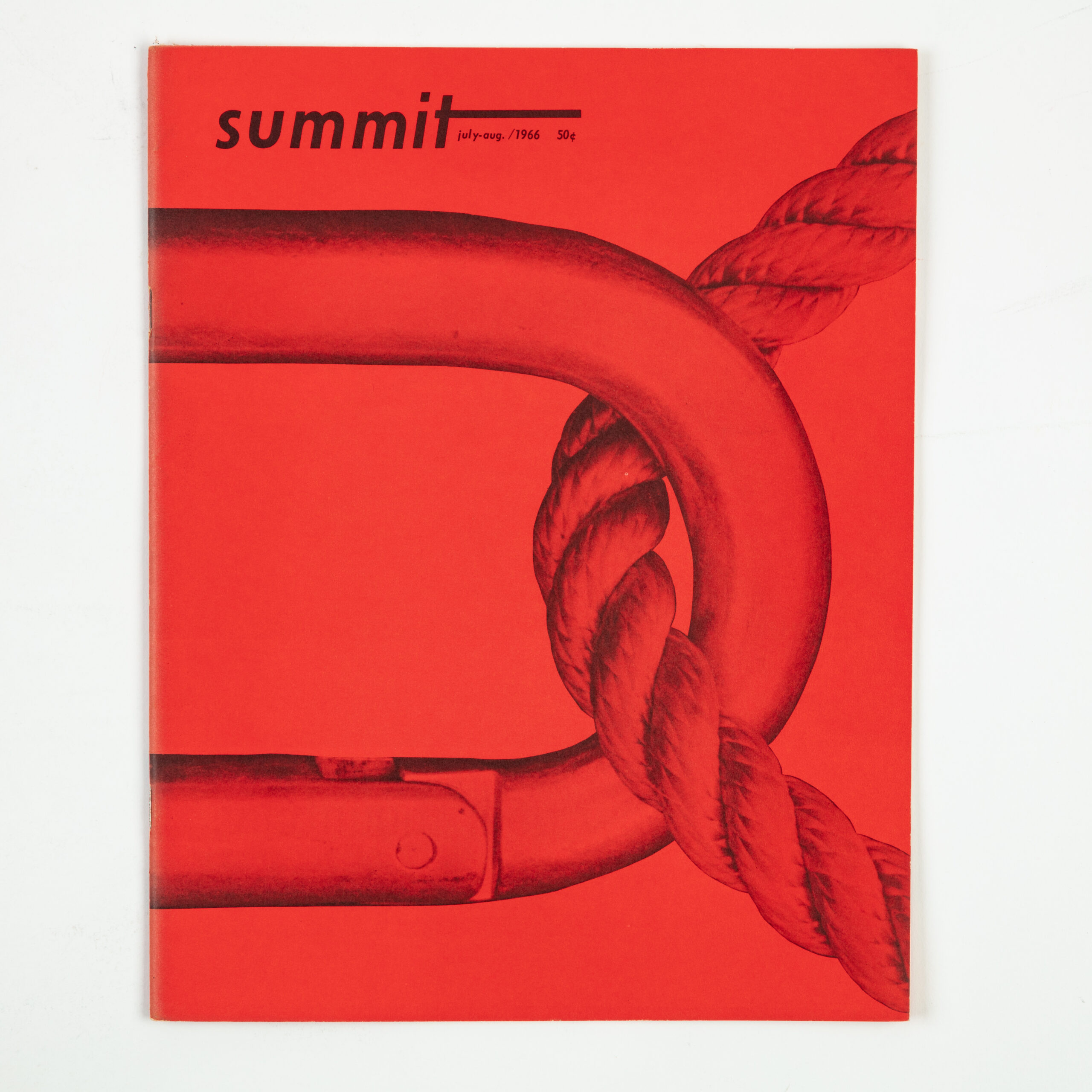

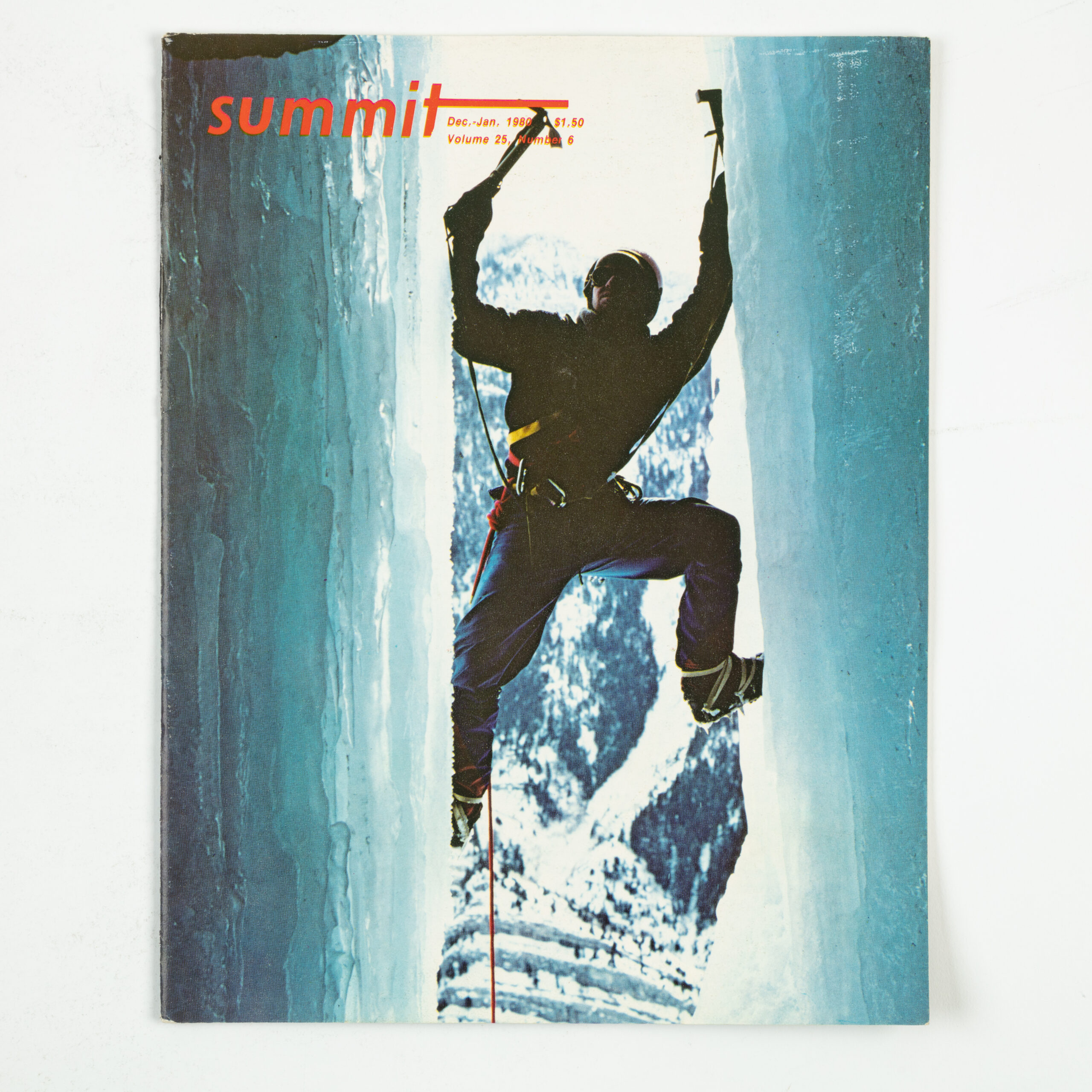

Beyond the personal side, I love the time capsule aspect of physical slides. Not only the content they hold but the little physical details, the fonts on the slide mounts, the discoloration on the edges, and the date stamps from 1974. These are from a different era, a different time. They age and change with time, there is life to them.

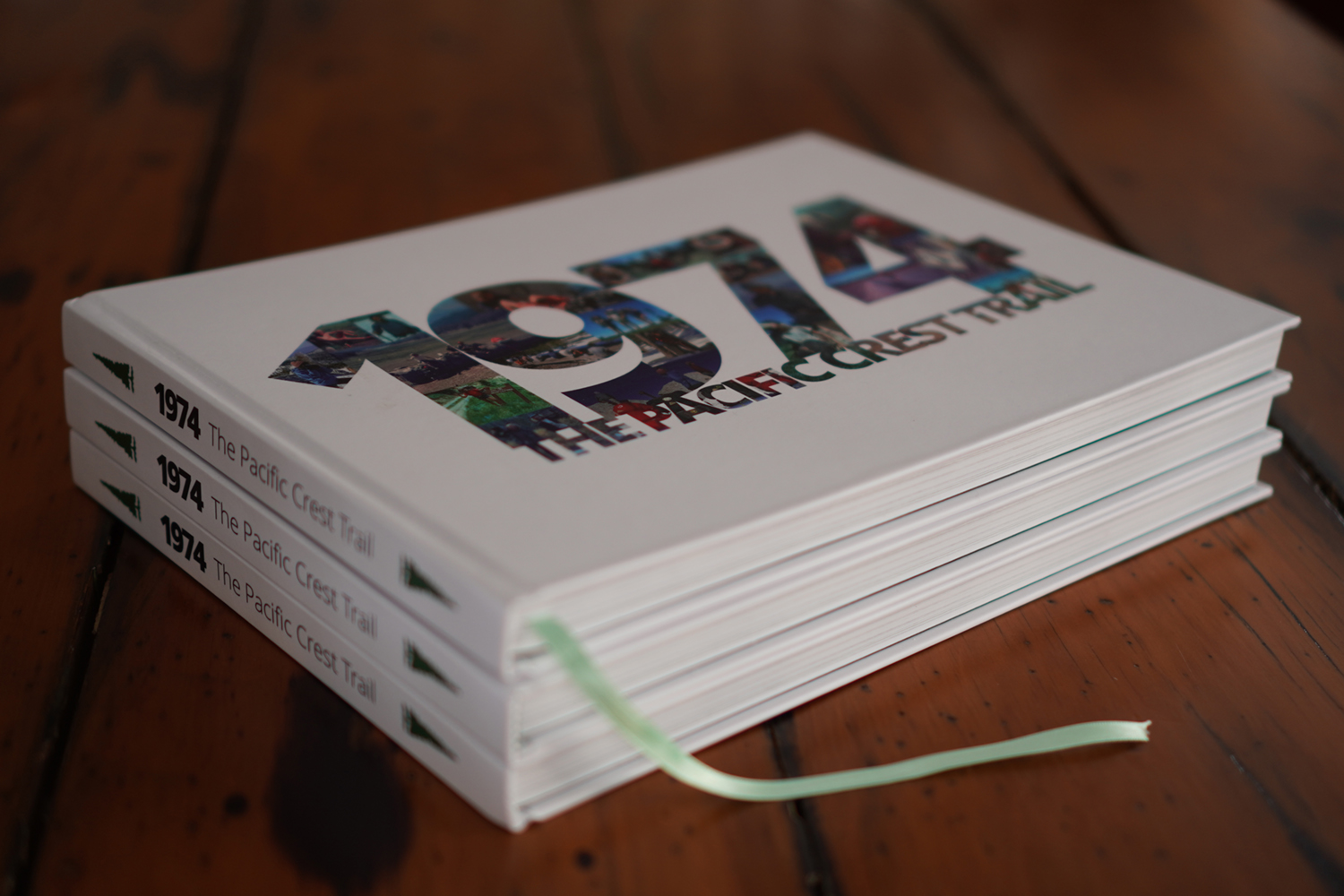

My father had handwritten numbers on the slide mounts. Those personal touches separate physical media from digital and give them that life. Now and again during the process, I would be struck by the fact I was holding slides that my parents had taken and curated over 40 years ago. These are the only records of this period in my parent’s life and some of the few images documenting the early days of thru-hiking. It made the project feel more profound. I made a point of putting scans of the physical slides in the book because they came to mean so much to me.

Since you’re involved in tactile experiences with The Postcard Project and other collages was this a different way to express a tactile medium?

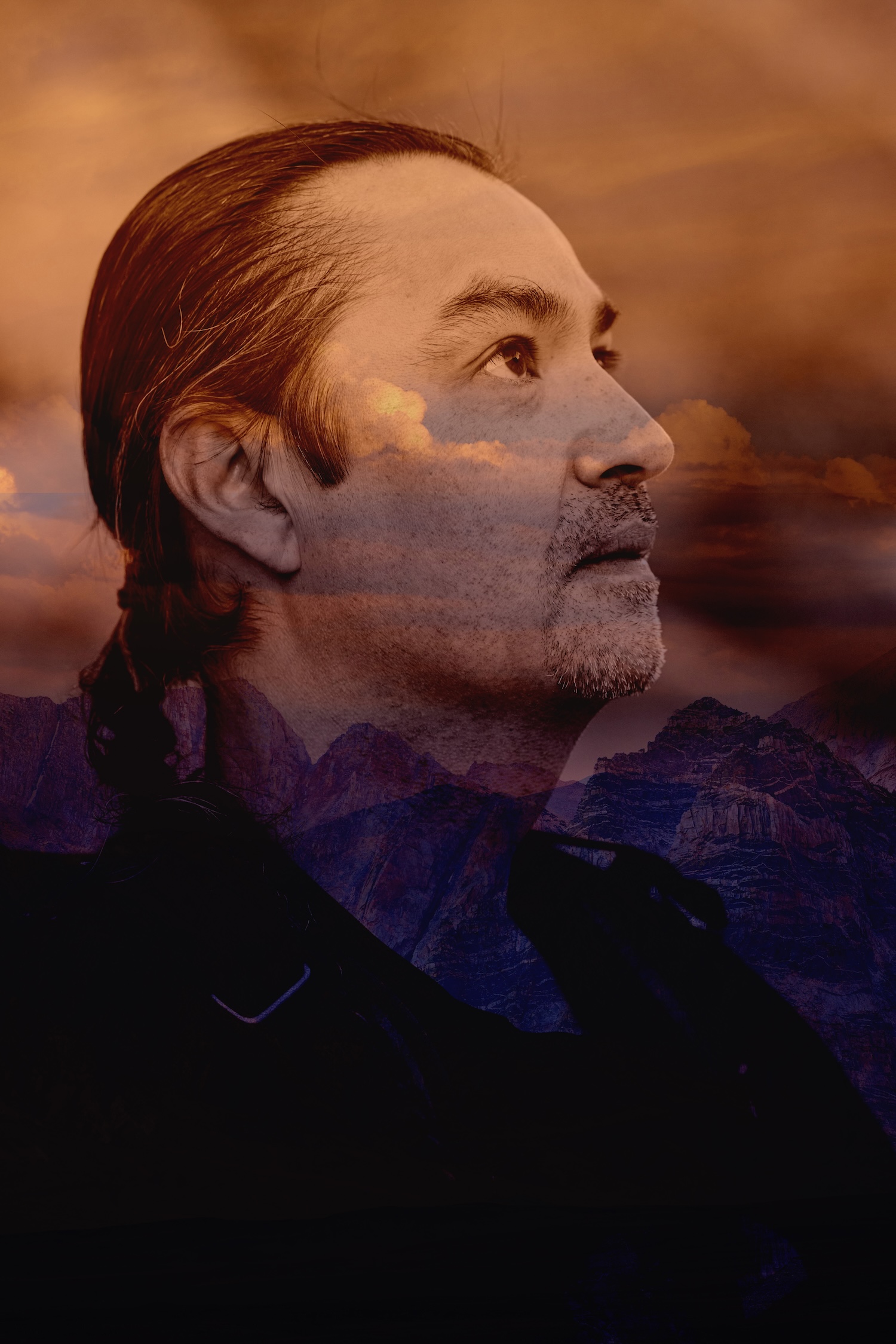

For the postcard project, I used vintage postcards from the 1930s, sketched blue ink portraits across three postcards, and mailed them separately to an unsuspecting recipient. The postcards share a lot of the little touches that the slides have. They are a tangible connection to the past, with a life to them. I have always been fascinated by taking something with that life and adding art to it.

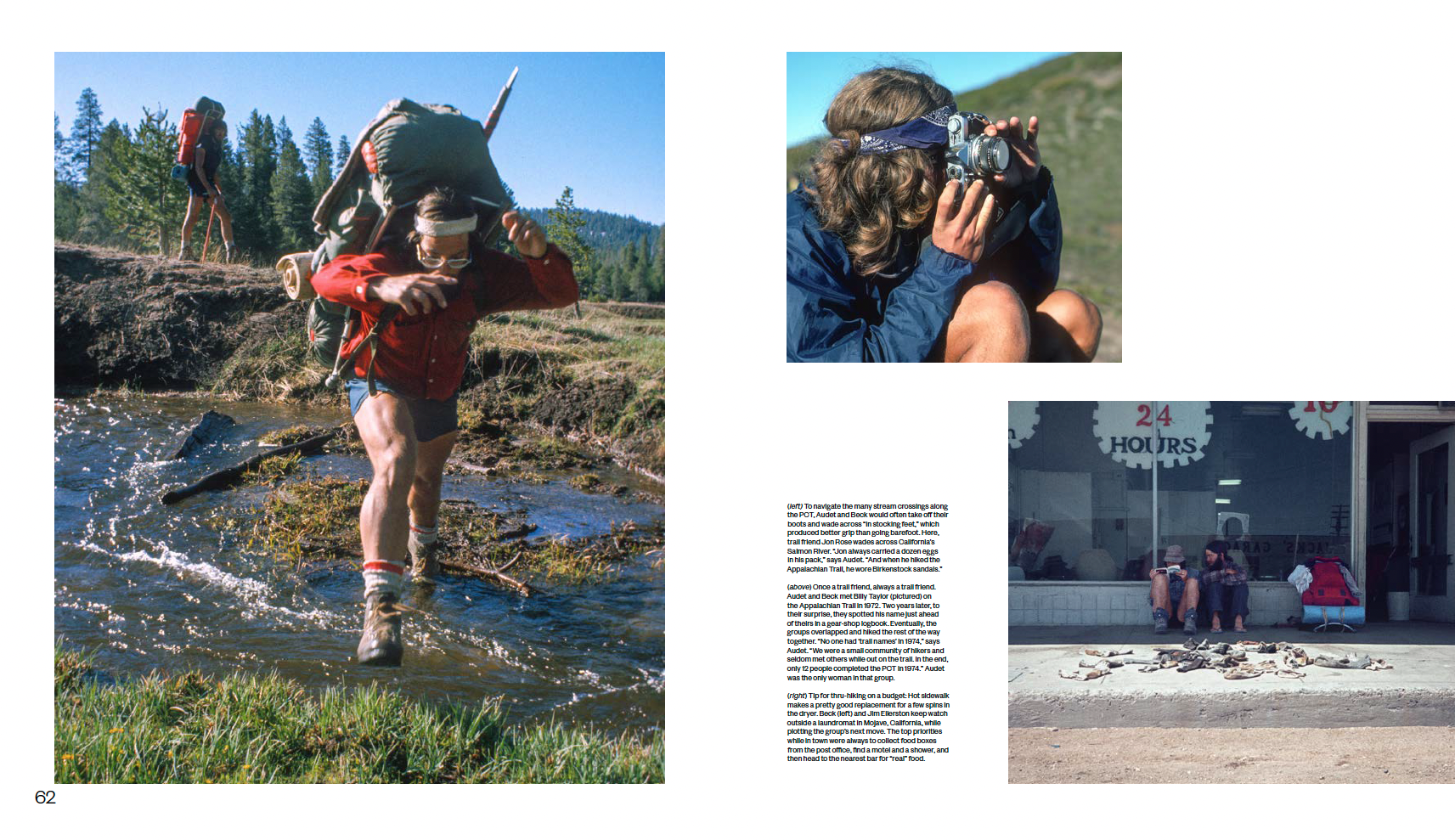

I think the key difference between the PCT project and many of my other projects was the process of first digitizing something old, then creating something new via software, and finally printing it as a new physical book. I relished the storytelling process through the layout while infusing some of my aesthetic and style. The challenge was retaining the life of those slides in something new. I specifically left some of the images uncropped with the jagged edges of the slide showing. These imperfections are increasingly important to art as AI can create near-perfect original pieces. It is the imperfections that make art human.

I am also really intrigued by physically mailing items to people. Today most people only get packages, bills, and marketing in the mail. We are losing that unique experience of being surprised by something showing up from someone we care about. The postcard project was an opportunity for me to create that experience for people. I sent one of the PCT books to my parents’ hiking partner Bill Jahn. He had no idea I was scanning the photos, let alone making a book. It caught him off guard and I got a very loving note from him afterwards. I don’t think you can have that type of impact with digital mediums.

Did your parents talk much about their archive?

In some ways, I don’t think they fully appreciated what the archive represented, to them personally and to the hiking community. There had been discussions about digitizing the slides but it was not a strong push. For many years, there was no talk of the slides at all. It made the moment they opened the book that much more fulfilling. I could see in real-time the realization of the scale of what they had done.

What do you think is lost in the digitalization of family archives/history?

One of the promises of digitization is that it will make the content more accessible. Instead of being stored in a stack of boxes, requiring a projector to view, they are readily available on a shared drive. The reality is that you don’t end up spending the same quality time with them. I still love flipping through photo albums from my childhood and lament that my kids don’t get that experience. This was highlighted the other day when my kids were going through the photo album on my Facebook page. I realized this was one of the only places they could see all their childhood photos. I am resolved to get some books of our photos printed now.

A task like this is daunting – how did you approach it?

It took nearly ten years to complete, so I’m not sure about my approach. I made a concerted push at the beginning, getting 400 or so done in the first month. Then I would do 50 in a go when I had time. It was such a repetitive monotonous process that it was difficult to keep the momentum. When I took a moment to review the images and saw how great they were, I got motivated and pushed for the next group to get done.

Were you always planning on making a book for your folks as a gift?

When I started, the only goal was to get the slides digitized and on a shared drive for my mother and father. Through the process of handling the slides and seeing the images for the first time in years, I began to feel they deserved something more. I don’t think you can engage as deeply with the photos through a screen. Once the book was printed, I spent hours flipping through it, finding new details and discovering new favorites.

Now that the book is done – what would you do differently – are you inspired to document your life?The book was made for my parents and as a result, I prioritized getting as many images in as possible. I laid out the book quickly. I wish I had taken more time on the layout and reviewed the photos closely. Once I saw the photos printed, some were much better than I had thought when I saw them on the screen and justified more real estate. I would also like to add quotes from those involved to bring more life to the images.

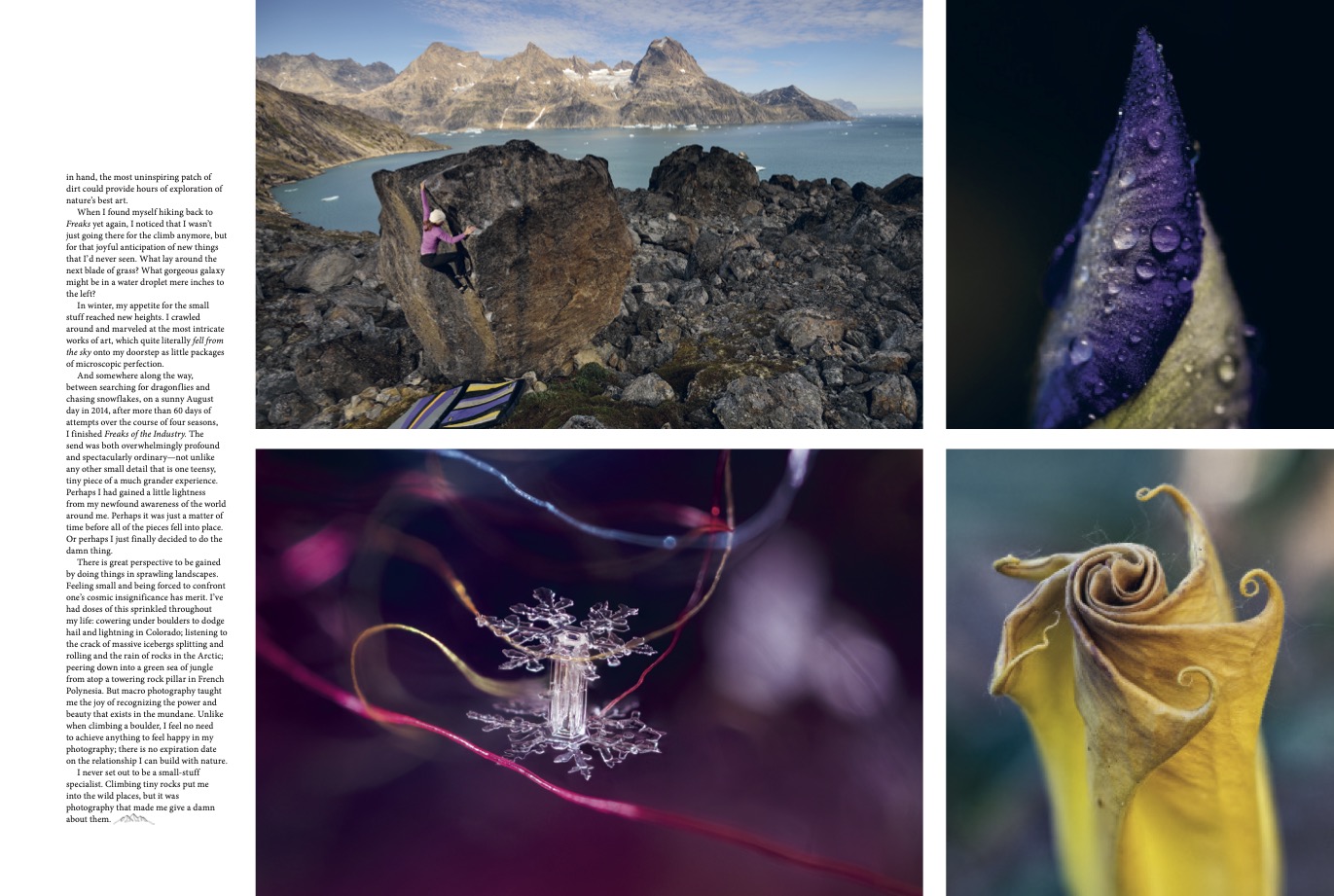

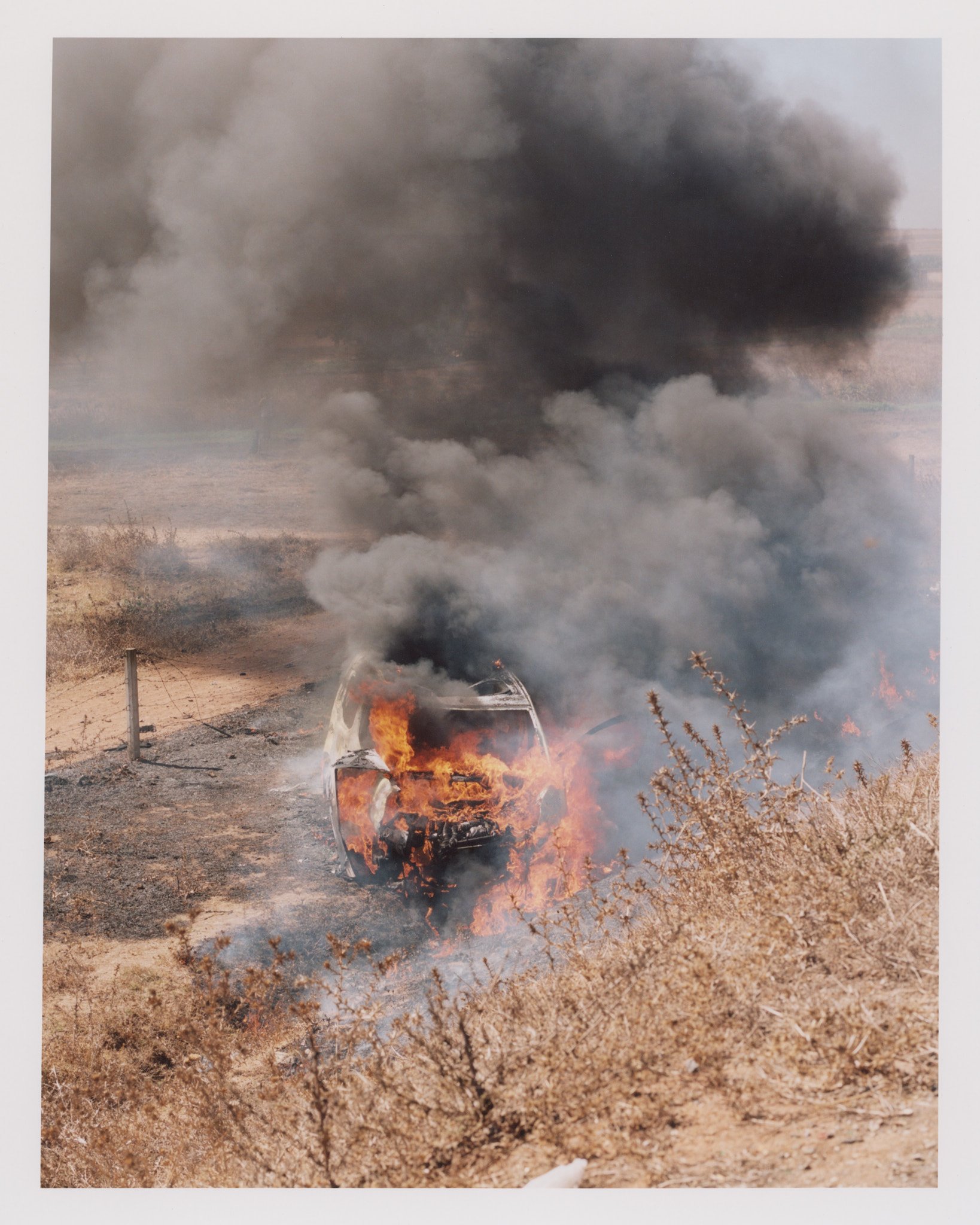

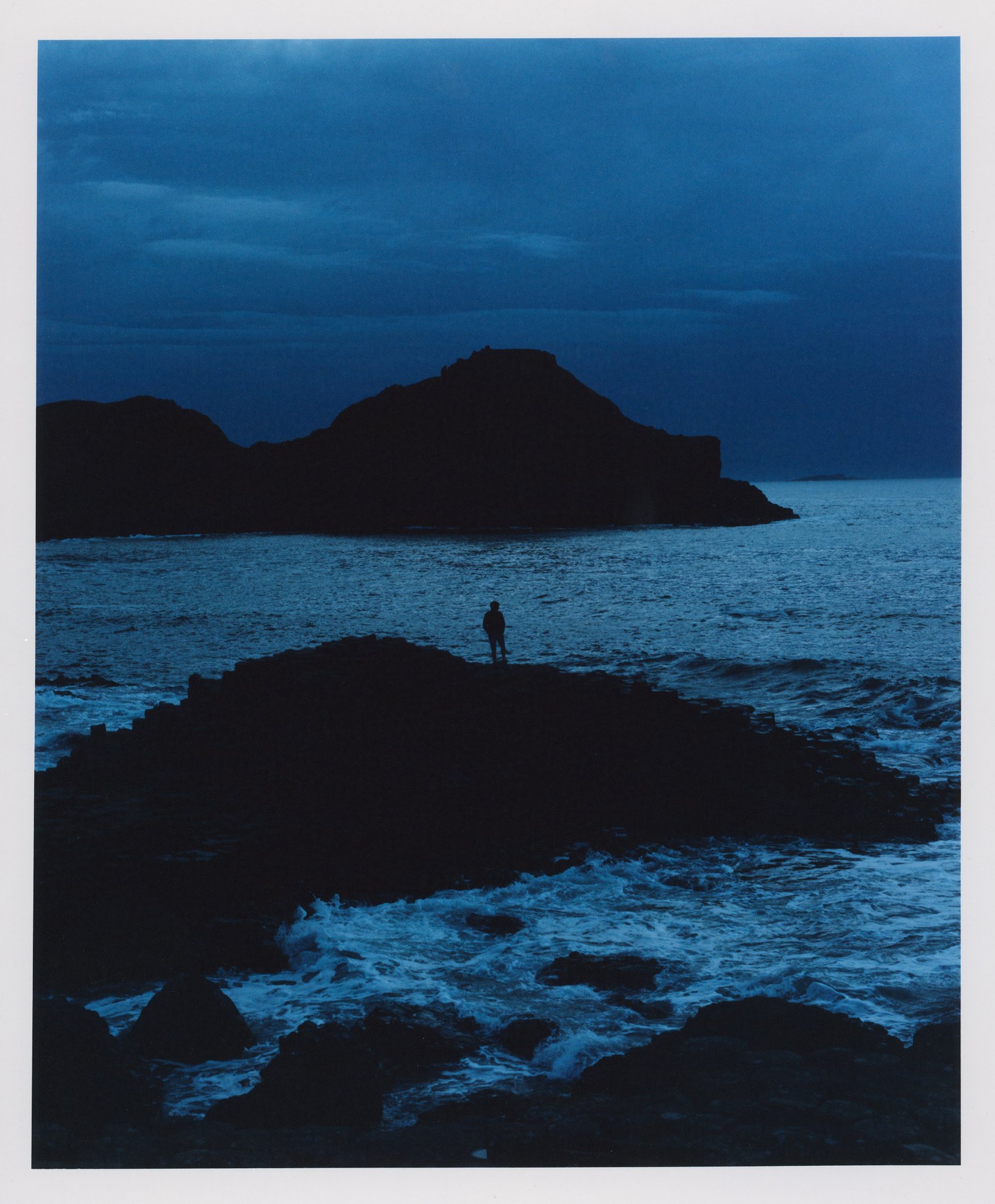

Personally, the process confirmed my belief that documentation, digital or physical, of these types of life experiences is important. It provides a way to relive the experience and to keep the memories alive. It made me commit to improving my photography skills and capturing as much as I could on recent trips to Greenland and Newfoundland.

Another offshoot of the PCT project was that I started doing public presentations of my trips. I had such fond memories rekindled of my parents’ slideshows and lamented that we don’t share our experiences like that anymore. I find it to be much more gratifying than simply putting up an Instagram post.