Fall 2022 Patagonia Journal

Photo Director: Heidi Volpe

Photographer: Danielle Khan Da Silva

Writer: Nikki Sanchez

Heidi: How have you used your talent as a photographer to reframe climate messaging and the grassroots narrative?

Dani: My whole life has changed in the small moments where I am shown the way—often through firsthand experiences, photos, stories, and films. This is why I am a storyteller—to try and share some of the insights and experiences I have been privileged to have with others.

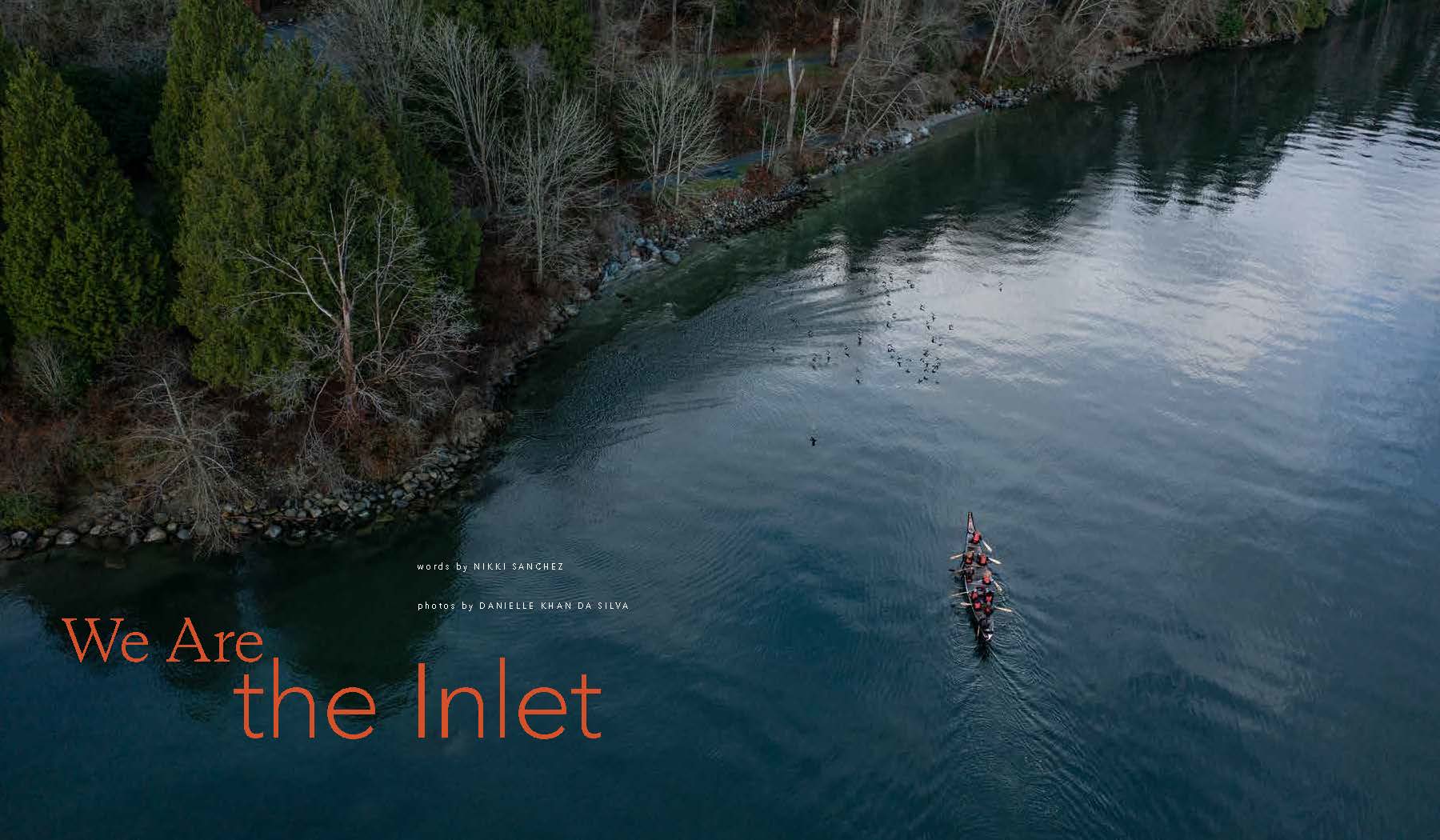

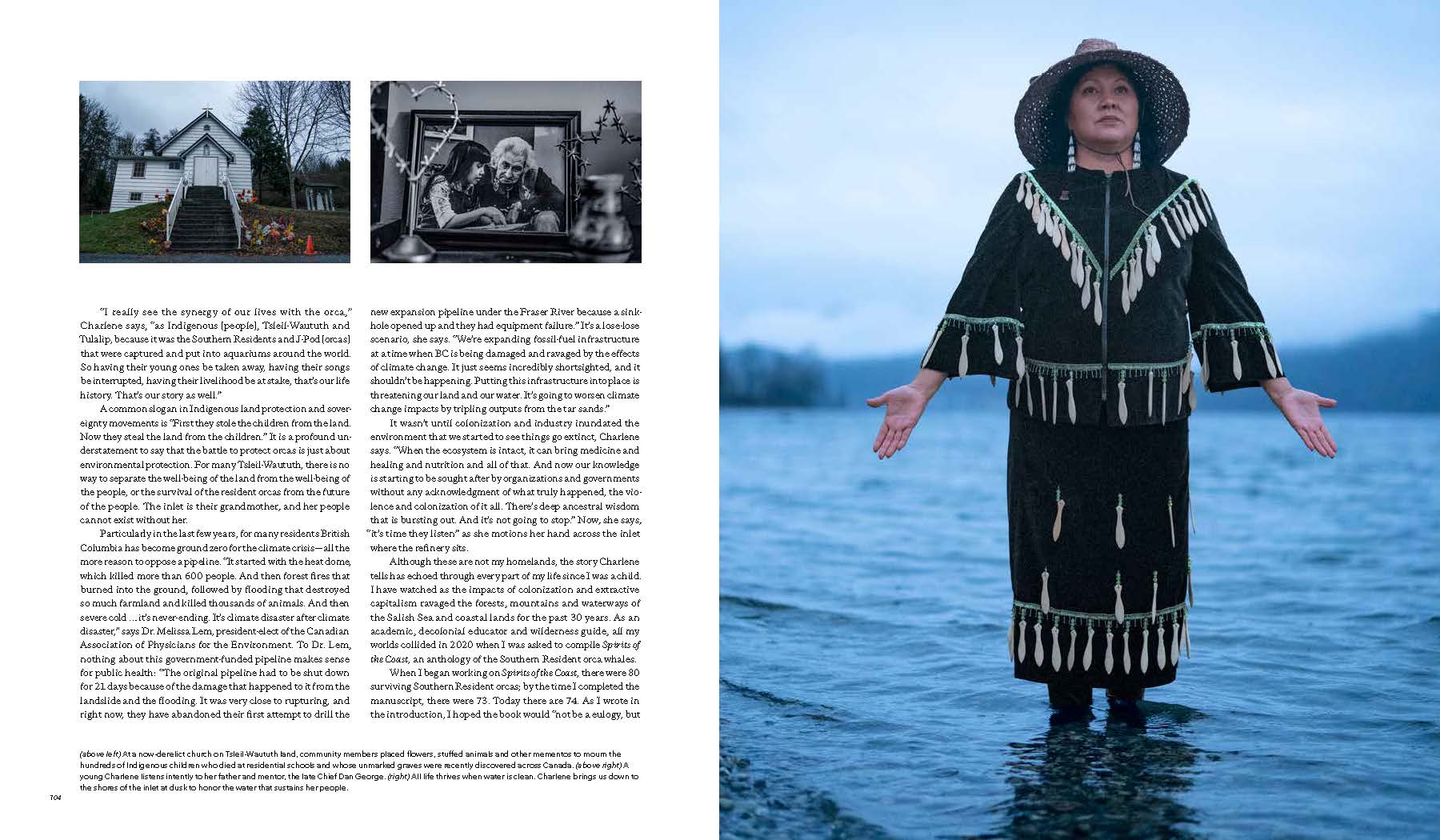

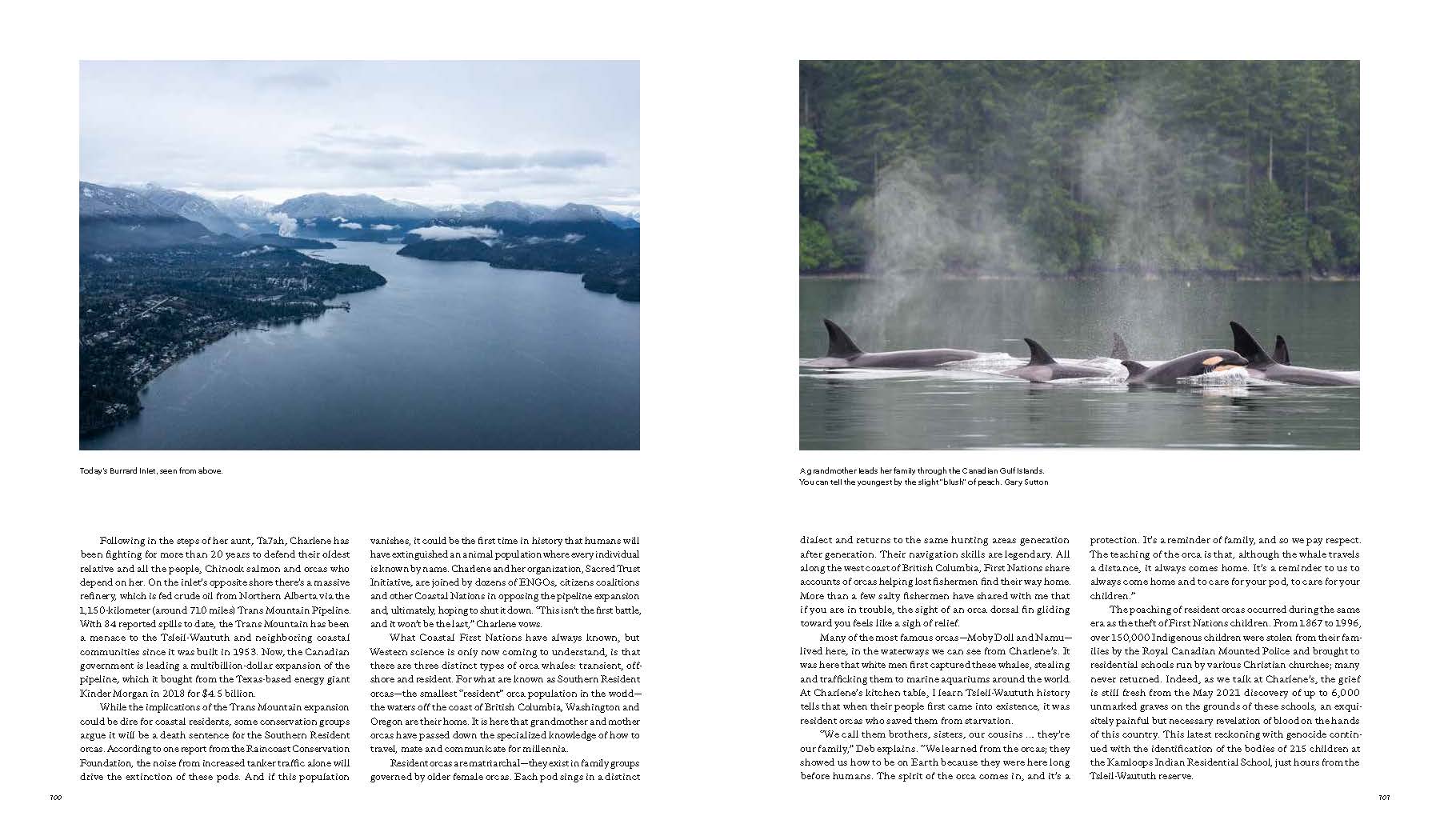

In 2018, for example, I went to stand with the protectors (kia’i) of Mauna Kea with Nikki Sanchez (the writer on the story included in this interview) I was first introduced to the concept of “kapu aloha” and was honored to be immersed in a space where this love-based conduct was being practiced, in combination with regular ceremony and teachings. I had a stark realization of how different things could be. This forever changed me—who I am as a storyteller, as a leader, and as a human. Similarly, with this story for Patagonia about matriarchy and intergenerational knowledge transfer featuring Kayah George of the Tsleil-Waututh nation, I learned so much; from the community’s gentle ways, to their strong and steady approach to fighting battles against monstrous entities, to their songs and connections to the orca whales. This is why I feel it’s so important to tell stories about people and communities that hold knowledge that many of us have become disconnected from through the impacts of colonialism. This knowledge—which each of us has from our own lineages—is what I know in my heart contains the keys to our future.

It’s obvious that we need to “do something” to mitigate climate change and protect natural habitats (our best bet is truly to keep intact what we have as much as possible—we are only beginning to understand the value and complexity of ecosystems and their services), but more importantly we need to address the underlying cause, which is disconnected human behaviour motivated by greed, consumption, capitalism, and other values that are not in alignment with a healthy and abundant planet for all. Further, this conditioned, colonial mindset disregards our innate oneness and interconnectedness to all things, which is a key underlying concept in many Indigenous teachings.

We humans are social learners who also mimic each other, so to address the toxicity that we have become so accustomed to, and to combat social numbing and apathy, we need to see examples of how we can be; see what becomes possible when we reconnect to our reverence for sacredness.

What was your biggest challenge and biggest celebration?

My biggest challenges in this story were a) getting into freezing cold water in a dry suit to document some of the images; and b) trusting that everything would turn out how it needed to. We had challenges with weather and time, and sometimes the process of surrender also feels like a celebration. It’s been really special to me to get to know Kayah more deeply.

How much did your studies, research and various degrees inform your approach to photography?

Quite a bit. I studied conservation biology, psychology, and did an MSc in Environment and Development. I learned a lot about critical thinking, and learned a lot about unlearning. There was something about the way I was being taught, what I was being taught, particularly in my undergraduate degree that I found really unsettling. I found myself questioning a lot more than we were being asked to—Why were the sources so limited? Why were we constantly referencing white conservationists and applauding trophy hunting and amplifying racist views about Indigenous peoples and their knowledge? I always loved Vandana Shiva’s groundbreaking work, for example, but her ideas on eco feminism were literally laughed at by some of my professors. In this way, we become conditioned. So while I sought out knowledge about how to protect the planet (from ourselves), I wasn’t satisfied by what I was learning in school on multiple levels.

I do find myself also applying a lot of my psychology background in my work. Systemic change is what is truly needed for us to make any significant changes, and for systemic change to occur, we need political will. Political will comes from the power of the people and our dollars.

For us to know our political power, I believe it helps to be intrinsically motivated—to cultivate an appreciation for personal and community growth, purpose, curiosity, cooperation, enjoyment, and expression. Intrinsic motivation essentially involves doing something because it’s personally rewarding, versus extrinsic motivation, which involves doing something to earn a reward or avoid punishment. Extrinsic values seem to be more closely related with a capitalist approach where we are constantly given messaging about what to buy or how to change ourselves, to be “winners,” to engage in competition, and to earn perks and benefits in exchange for a behaviour. My studies into psychology have revealed that the more we strengthen extrinsic motivation, the more we weaken intrinsic motivation and vice versa. Most communications today strengthen extrinsic motivation, yet there is a real case to be made for strengthening intrinsic motivation for us to be the change we hope to see.

Shifting the values of the dominant culture is not easy. The dominant culture values consumption, capitalism, exploitation, convenience, comfort, etc which are not aligned with the values needed to support all beings into the future in a healthy way. I see the majority of climate change messaging as being very “distant” to most humans, and very difficult to relate to. To bring it closer to the heart means moving people to recall their own connection with all that is sacred, and to foster a reverence for this beautiful creation we are a part of.

Photography has allowed me to learn so much by being a witness and understanding peoples’ lives and stories.

What behavior change or mindset do you hope to challenge with this work?

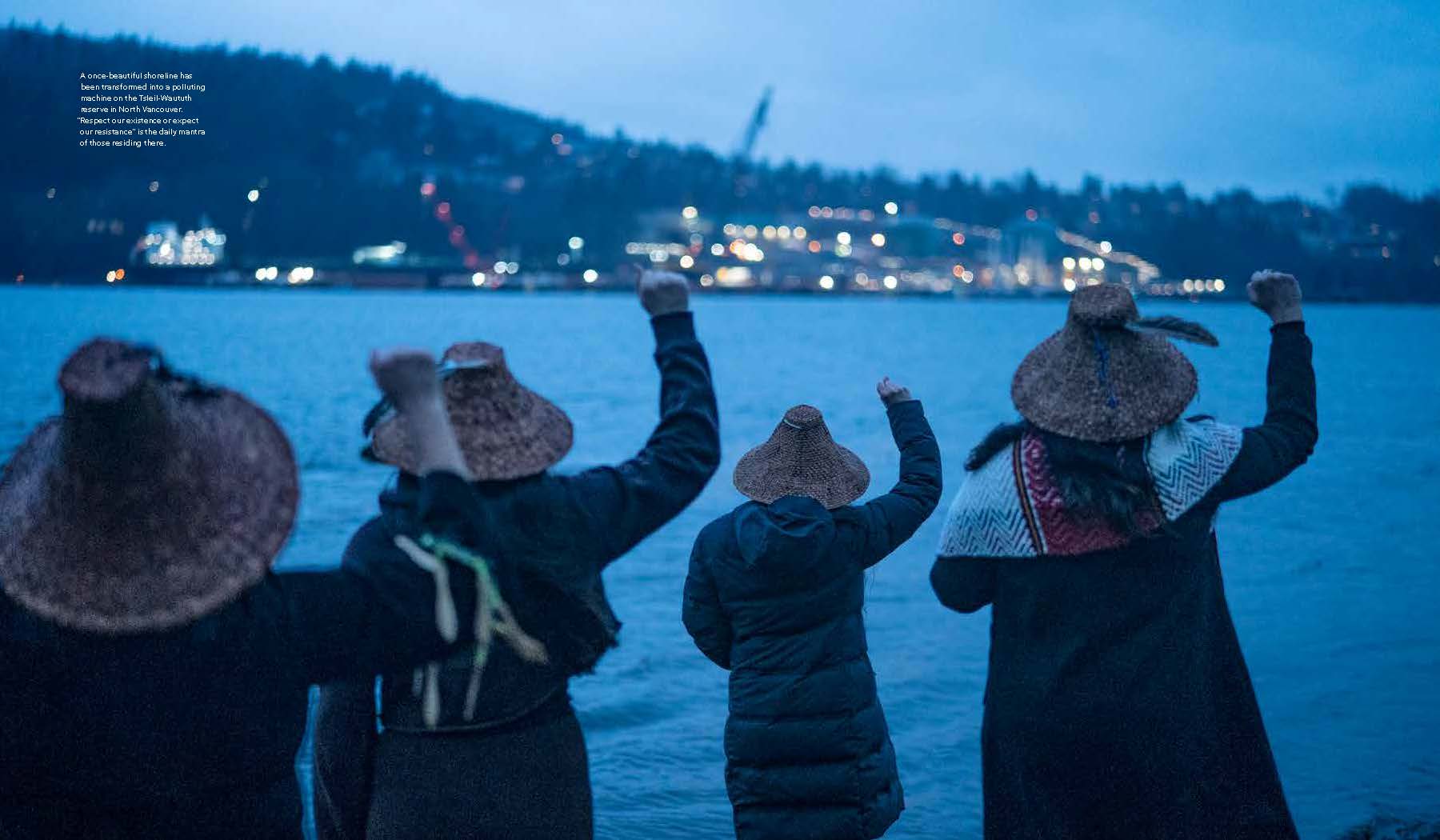

I personally see it as my responsibility as a settler in so-called Canada to do whatever I can in exchange for living here as a treaty person, and I urge those situated on unceded land (95% of so-called British Columbia is unceded yet settlers keep taking up residence there, and the coastlines continue getting affected by oil spills/toxicity, noise and light pollution, development, etc.) to think about their obligations as guests.

My hope is threefold:

1) To further the collective healing process (Recently, our MPs voted unanimously to name what has happened in so-called Canada with residential schools a genocide that has affected Indigenous peoples across the nation, and acknowledging the harm is an important step);

2) To ensure the Tsleil-Waututh know they are not alone in their fight to stop the TMX pipeline expansion and other extractive entities from destroying the land and putting the inlet and their kin (human and non-human) at risk from oil spills and other disasters. They need much more support from settlers. This is not just their fight, it’s all of our fight. And what’s at stake canning be replaced.

3) That settler audiences will see these stories and do their part to advocate through their votes and voices. Indigenous people are responsible for protecting 80% of the biodiversity on the earth but make up only 5% of the population. Science is only beginning to catch up to what Indigenous people have already known. They also make up 5% of the population in so-called Canada but make up a disproportionate percentage of prison populations, suicides, children in foster care, and violence against women due to the prevalence of systemic racism and colonized mentalities.