Everyone I know hates this time of year.

People get sick.

It’s cold and gray.

The dried grass is brown, outside my window, taunting me for lack of snow.

Trying to turn my SAD upside down, I recently started limiting my time on social media, and replacing it with a strenuous 45 minute hike up the hill that rises above our family farm.

It sounds like a headline from the Onion, I know: “Bougie artist discovers exercise is better then sitting on your ass!”

But seriously, I’ve decided to trade the incessant internet chatter for bird calls, and the occasional barking dog. (Until it’s frozen and icy, I’ve made myself a good trade.)

Not sure it would work for you, but since when have I been shy about giving advice?

Today, on the hill, there was a moment that took my breath away. A raven, (we have many) was soaring in the sky when all of a sudden, in an instant, he tucked his wings in and dove down.

It was straight free-fall, but he/she was totally relaxed. It was only for a couple of seconds, and then the wings were out again, but it was so graceful, the nosedive.

Falling, effortlessly, because it’s much more energy-efficient than doing anything else.

I thought immediately about falling into this, the hardest part of the year. Then end, when my family is always crisper than a bagel that’s been left in the toaster for too long. (Translation: very crispy.)

There are so many jokes we could make about 2017, this endless year, but Twitter, (which I’m cutting down on, wink wink,) has been ablaze with them.

Here are a few of mine.

2017 has been longer than Donald Trump Jr’s collective community college transcript.

If 2017 were a greeting card, it would say, “Hey, Fuck-face, why do you think you deserve a card? Nobody deserves anything in this world, unless I say so. Life is difficult, and merciless, and only the strong survive. Get used to it!”

If I got to write one tweet, pretending to be President Donald Trump, wrapping up 2017, I would write: “Who needs #280? Hillarys a witch. And a LoseR! Burn her. Obamas muslim. Access tape faked, just like the news. See you in 2018. Trump out!”

Ok. Ok.

I’m done.

I think it’s a bit cathartic, for me, making fun of a sad situation. But let’s turn that frown upside down.

If you saw the headline today, you’ll know this article is the second, (and final) installment of a brief series about the best work I saw at Review Santa Fe 2017.

We’ll begin with Amy Lowey, who was my last meeting at RSF. We were both fried, as it was the end of the festival, and there was a moment where I thought it was going to go wrong.

But before you know it, we course-corrected, and had a deep conversation, in which she showed me work I found captivating. In particular, her black and white digital prints, on what seemed like a coated rag paper, were exquisite.

Her story was a sad one, as Amy has to be a care-taker for her husband, who has a degenerative, and likely fatal disease. It takes a toll, as one would imagine, and she goes for nature walks to calm herself down.

Amazingly, and symbolically, Amy has zeroed in on trees in the forest, particularly ones with symbiotic connections to other trees. Wow. I’m choking up just thinking about it.

Like Amy, Ward Long is a recent graduate of the excellent Hartford low-residency MFA program.

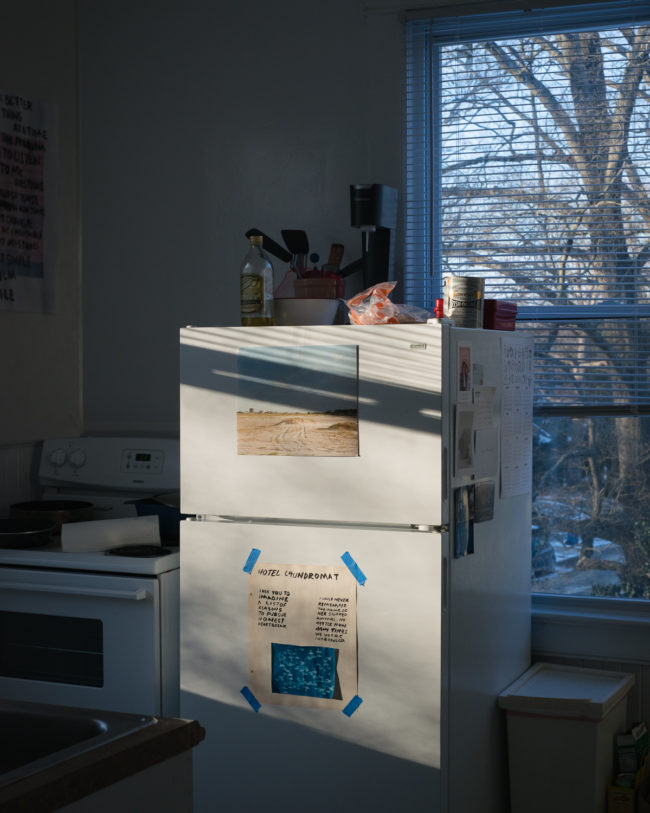

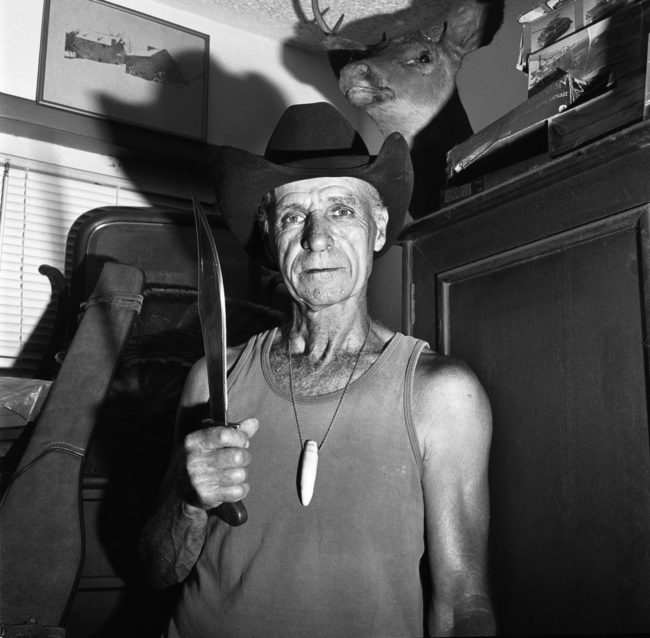

I spied his prints, with the side-eye, as I walked along at the portfolio walk on Friday night. The quality of his image-making, likely with a big camera, caught my fancy. I’d say it’s a part of that Southern-poetic-aesthetic, and having looked at his website, I feel comfortable making that call.

I had a similar experience with Mitsuharu Maeda’s work, in that it grabbed me as I walked down the busy aisles at the Santa Fe Farmer’s market, battling the throngs. (It really is an excellent venue for this sort of thing. Kudos!)

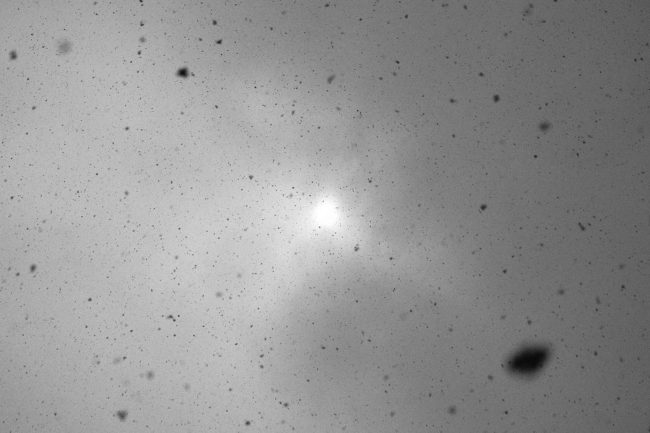

As Haruki Murakami is likely my favorite author, I’ve always been a sucker for elements of Japanese culture. In particular, imagining the cold northern mountains of Hokkaido.

So I was always going to like these snowy pictures.

Melanie Metz had recently moved to Santa Fe, so it was nice to meet a new member of our Northern New Mexico photo community. (Welcome, Melanie. Lucky for you, there’s no official hazing ritual anymore, after the Bad-Burrito-Incident of 2010.)

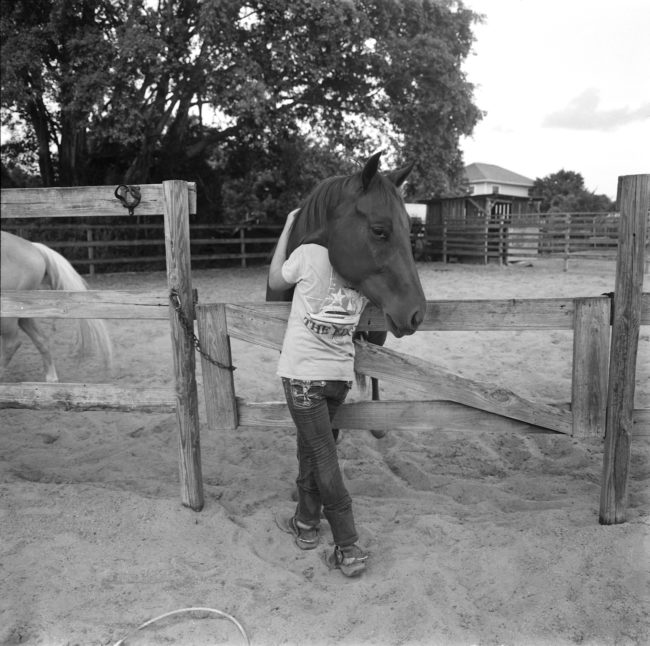

Melanie had some cool photographs of her hometown in Florida, which was not-too-far inland, but had all the horse-farm vibe of a Deep South or Western ranch. We discussed that I preferred her color to her black and white work, and I suggested it was normal for one “eye” to be more advanced than the other.

But she’s still pretty young, so I’m curious to see how Melanie’s work evolves over time.

Oren Lukatz, an Israeli, had some really interesting pictures of Israeli military soldiers, often with dogs. I questioned the addition, as it seemed random, but Oren told me the dogs are drafted too, just like the humans. Even better, their “master,” the solder who’s in charge of them when they retire, gets to keep them as a pet.

Pretty cool.

Finally, last-but-not-least, we have Kiliii Yuyan, whom I did not meet at all at Review Santa Fe. He was there, and he reached out a bit afterwards to say he had wanted to meet, or get a review, and it didn’t happen.

Several times, in the past, I’ve included such people in the round-up, if I liked their work once I checked out the website. In this case, it was hard not to like.

Kiliii is an indigenous artist from the Arctic, making work from inside his community, rather than from an outsider’s perspective. That’s another conversation I won’t make us rehash, after the big series in Summer 2017, but clearly these pictures have something extra.

Do yourself a favor and watch some of the videos on his site as well. Talk about getting into a meditative state? Like a diving raven?

I think you get the point.

7 Comments

Nice crop of photos all around to end up the year- almost!

Always like your selections…and the jokes.

Some really nice work. Thanks for sharing.

These are all beautiful images. I love the Santa Fe area and hope I can make it out to the review next year!

NIce work- Very intense and personal

[…] Blaustein, a writer for the NYTimes Lens Blog as well as for APhotoEditor, is one of my favorite photography writers. He’s got a stream-of-conciousness style, taking […]

[…] Blaustein, a writer for the NYTimes Lens Blog as well as for APhotoEditor, is one of my favorite photography writers. He’s got a stream-of-conciousness style, taking […]

Comments are closed for this article!