It all began when I forgot my cell phone.

(Which is rare.)

It’s a strange feeling, like being naked except for your socks. There’s a discomfiting sense of incompleteness when our devices are left behind.

I was driving Theo home from soccer practice last night, when we’d normally be eating dinner. Instead, we began our ascent of Blueberry Hill, just as the sky turned crazy.

As photographers, we know how crucial light is to our end product. No matter how hard I stress the point, my students still don’t get it, as appreciating illumination is a life-long endeavor, and they’ve only just begun.

But last night… any fool could see things were special.

Climbing in 2nd gear, right behind two big pick-up trucks, I looked to East to Taos Mountain, which was glowing amber. When green trees turn gold, every photographer reaches for the camera.

So I did.

But it wasn’t there.

Instead, I’d been given an opportunity to really look. I often feel that photography, while freezing time for the future, actually makes it more difficult to revel in the present.

Thinking about taking pictures leaves less RAM for appreciating what’s in front of you.

By the time we’d crested the hill, it had begun to rain lightly, even though the sun was beaming in the West as it dropped towards the horizon.

We cut across the Taos valley, everything before us shining like a swarm of lightning bugs in July. I turned to Theo and said, “We’re definitely getting a rainbow out of this.”

As the car sped North, there it was. Not one rainbow but TWO! (The Double-Rainbow being a New Mexico speciality.)

We call it walking rain, out here, when you can see curtains of moisture, from the clouds to the ground. It is beautiful, of course, but you get used to it.

Nothing could have prepared us, though, for the massive mist of walking rain, gleaming copper, enveloping the mountains, slashed in two by the double-rainbow. The ROYGBIV colors were so intense, reality became a hyper-real touch-screen.

Air, something you normally can’t see, was multi-hued, and it was so luscious that I wanted to reach right through the silver Hyundai’s window and touch it.

Theo kept saying, “Take a picture, Dad. Take a picture.”

But I couldn’t.

Then, and I swear this is true, a huge lightning bolt rent the sky, right between the two rainbows. Theo and I screamed aloud, as words failed us. (Today he said, “It was magic, Dad. Actual magic.”)

Four cars pulled off the road rapidly, as if they’d blown a tire, so the drivers could snap the perfect Instagram square.

I kept reaching for my phone, like a phantom limb, but it was futile.

We lived those 15 minutes, and I can recall so much more now than if I’d tried to capture it. It’s a paradox, especially for an audience of photographers.

Is it ever a good idea to just put the camera down and watch?

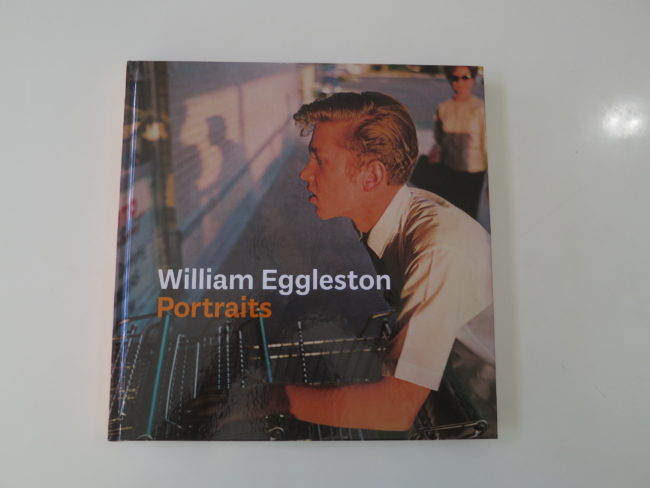

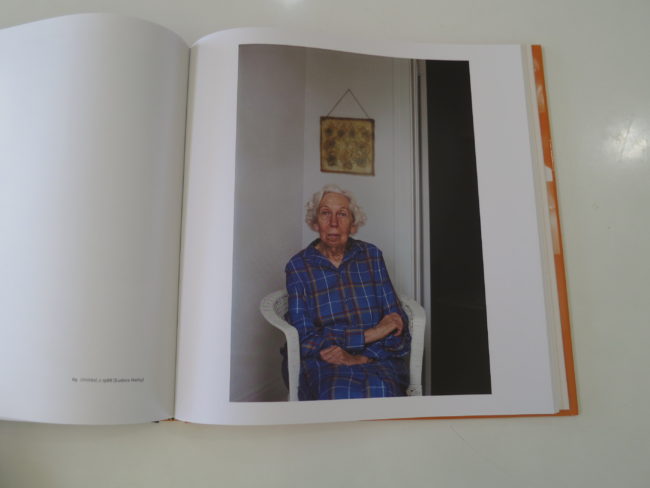

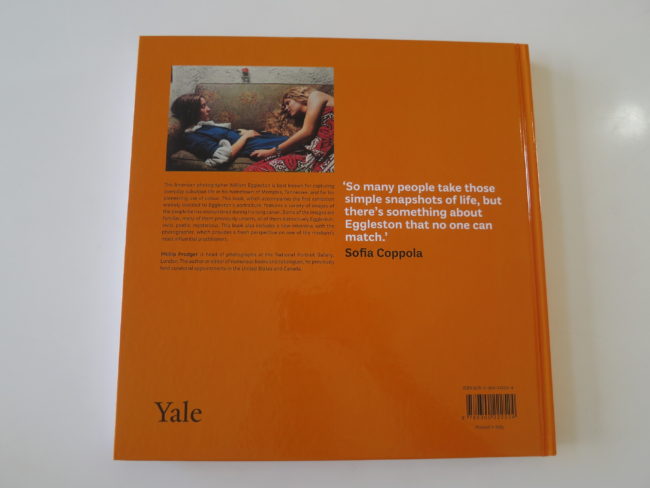

I ask you, now that I’ve just finished with “William Eggleston: Portraits,” a new book that turned up in the mail from the National Portrait Gallery in London. (Thanks guys!) I’ve been meaning to show you this one, and today’s the right time.

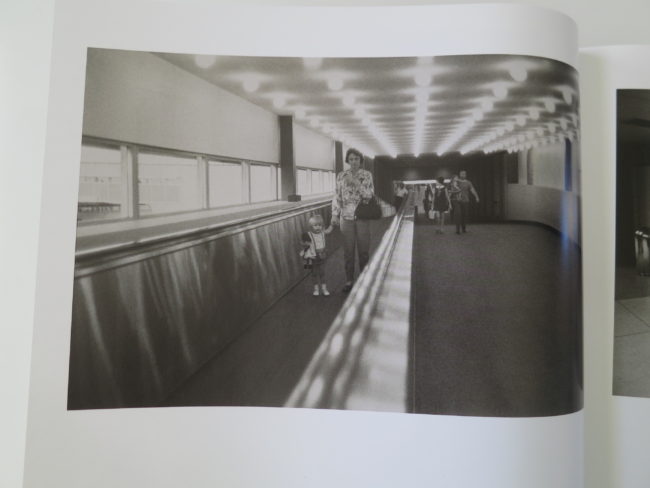

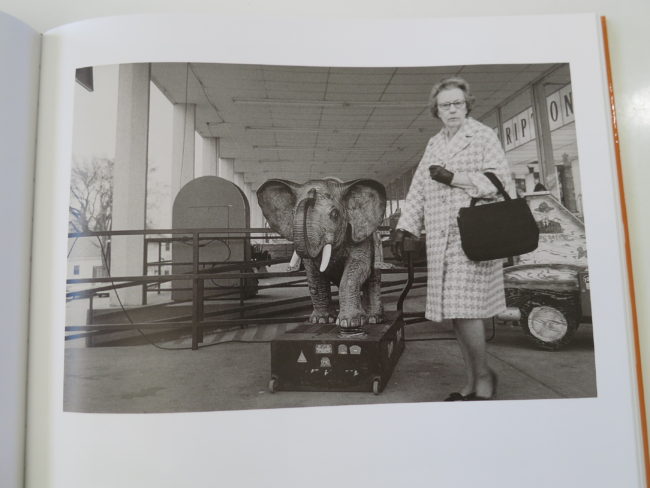

It’s a perfect foil for the Diane Arbus book we reviewed two weeks ago, as this also introduces a black and white vision that pre-dates what we know of Eggleston’s masterworks. (You might recall I reviewed his brilliant “Los Alamos” project earlier this summer.)

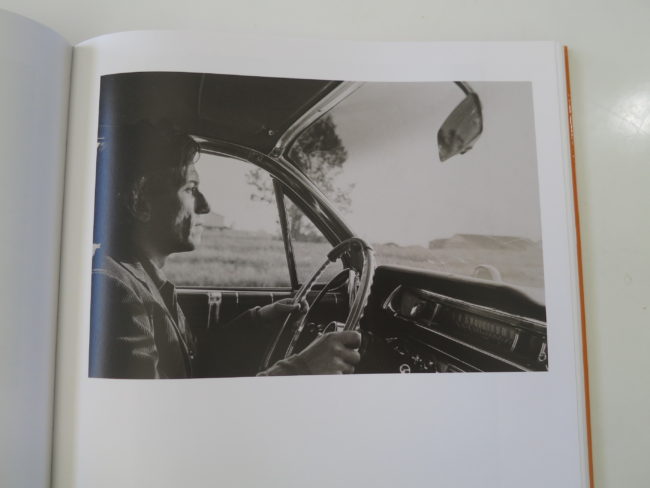

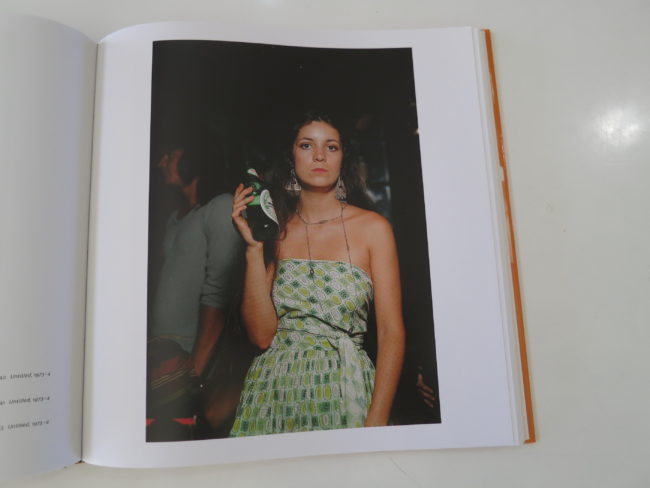

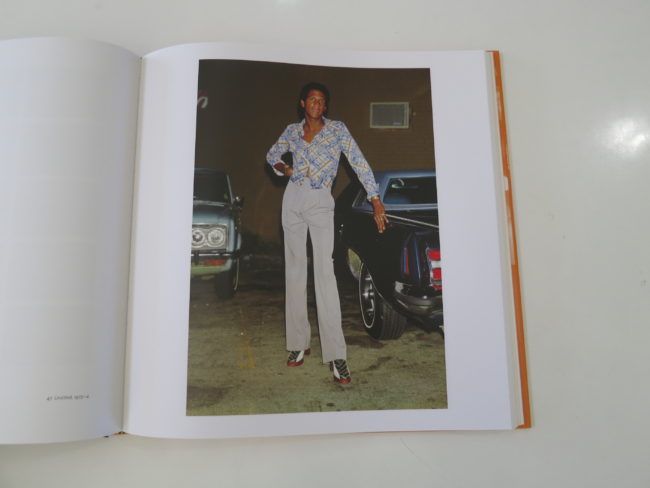

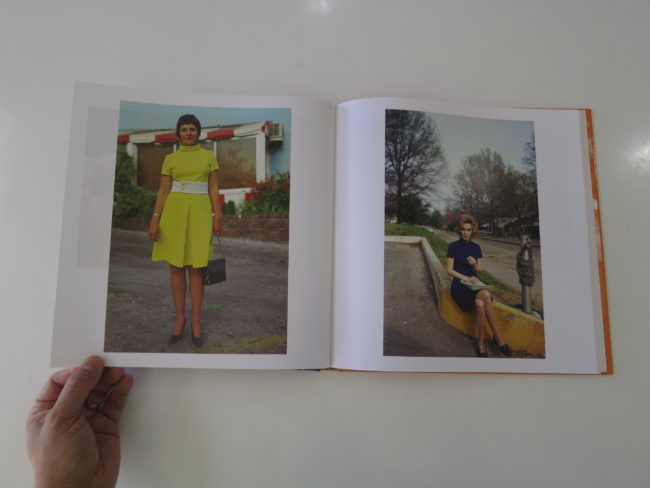

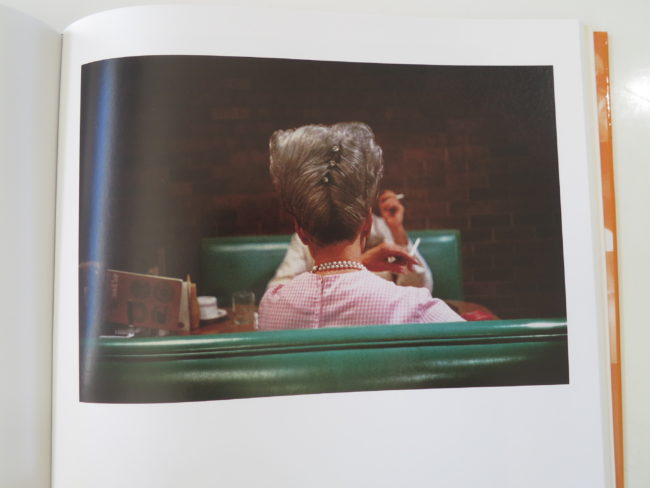

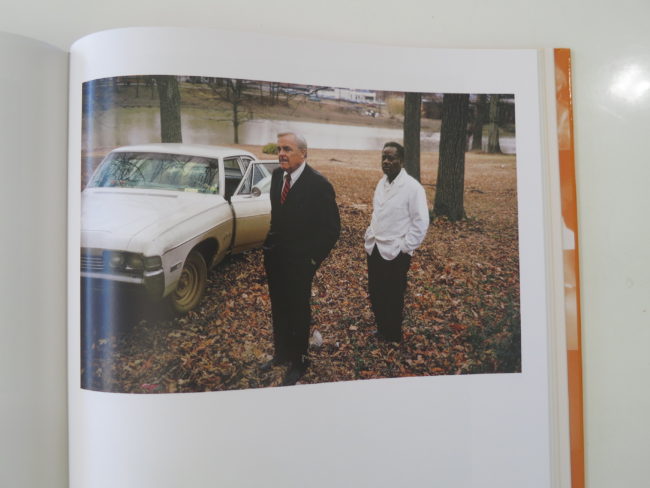

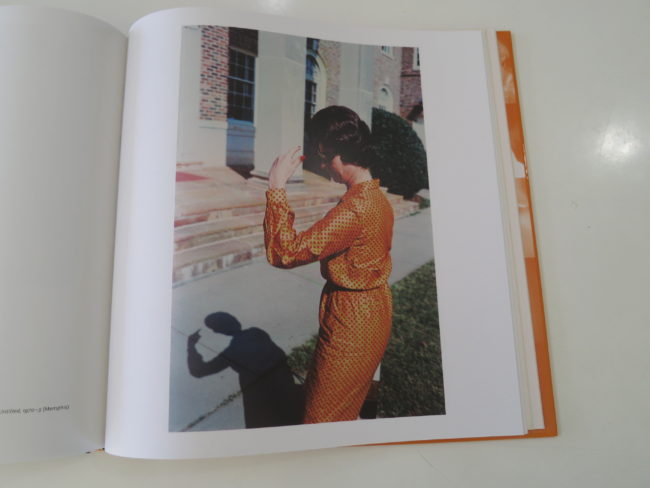

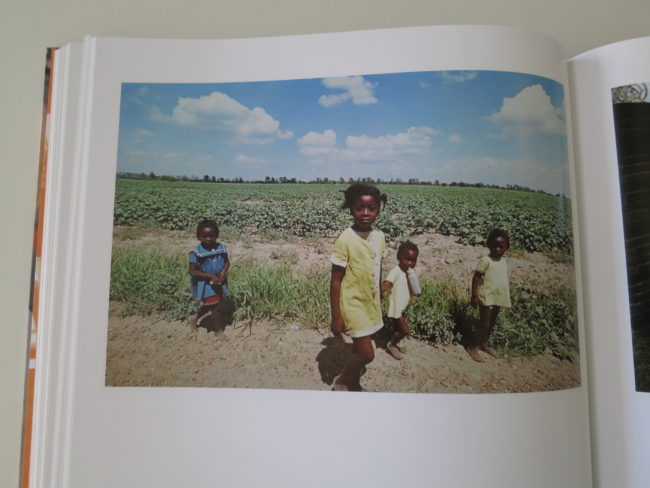

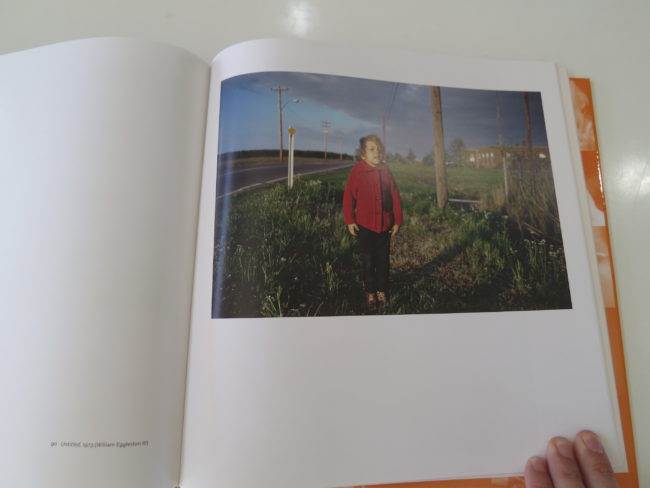

As I wrote then, William Eggleson’s mature work, his rambling American color photographs from the late 60’s and early 70’s, is as good as anything that’s been made. He owns color; a certain saturated palette in particular, and you’ll have to claw it out of his cold dead hands.

So what was this black and white then?

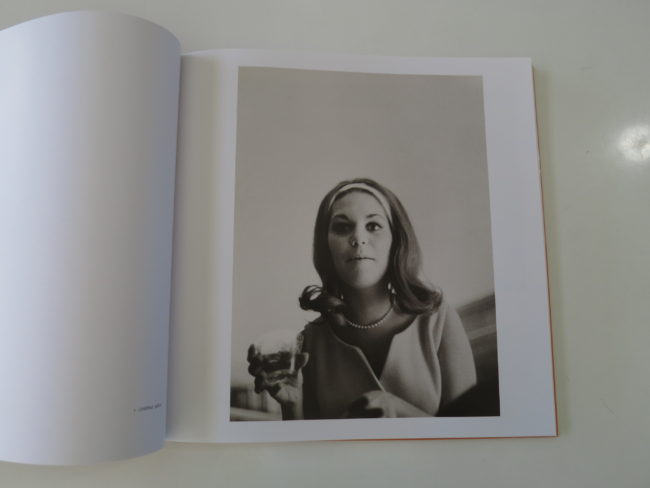

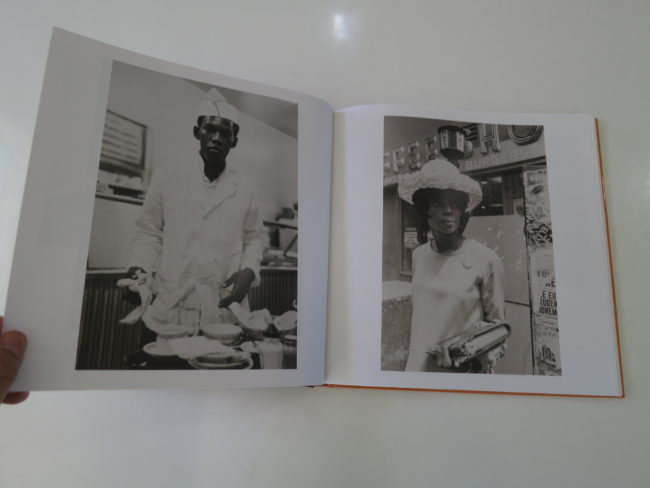

Unlike Ms. Arbus’ early 35mm photographs, which contained the tension inherent in her later work, these early pictures look like they could have been made by any number of people. They’re exploratory, rather than resolved.

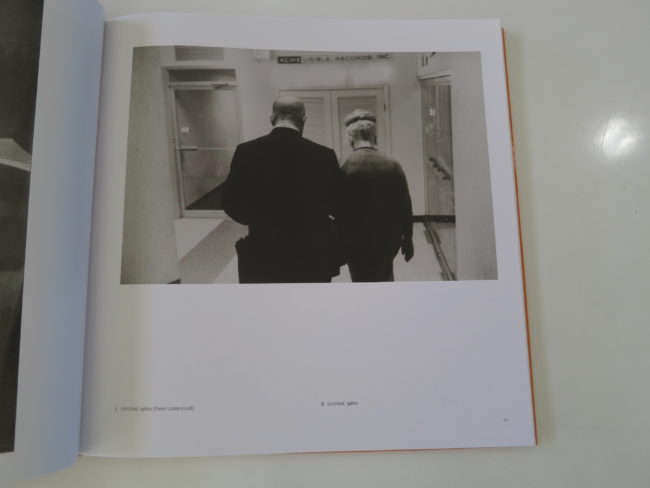

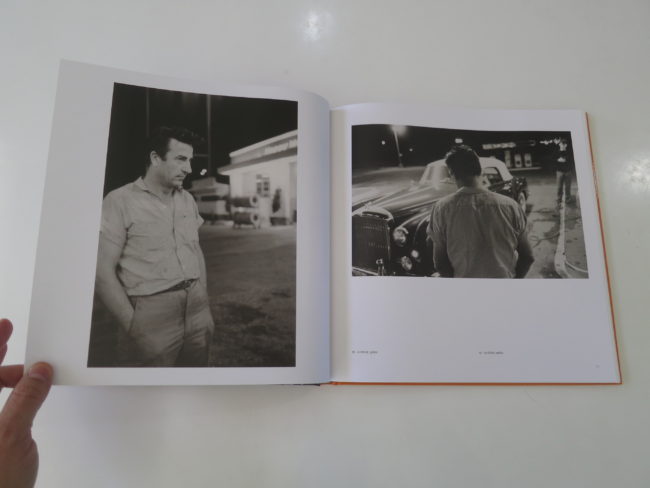

They’re good, don’t get me wrong, but there’s a big chasm between good and historically great. There’s even a photo that looks suspiciously like a Robert Frank picture from “The Americans.” (You’ll know it when you see it.)

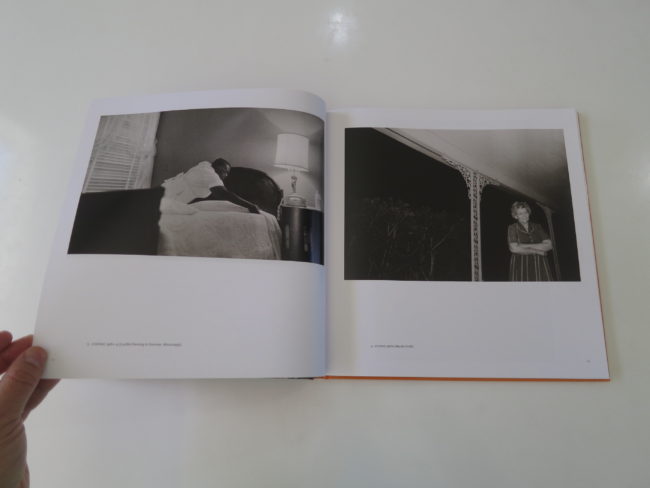

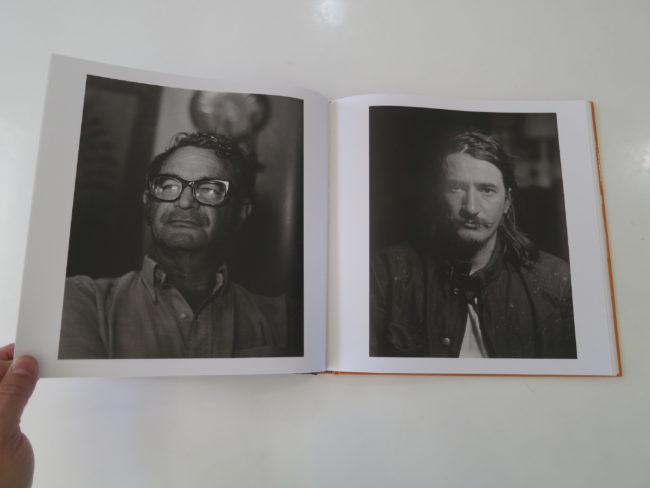

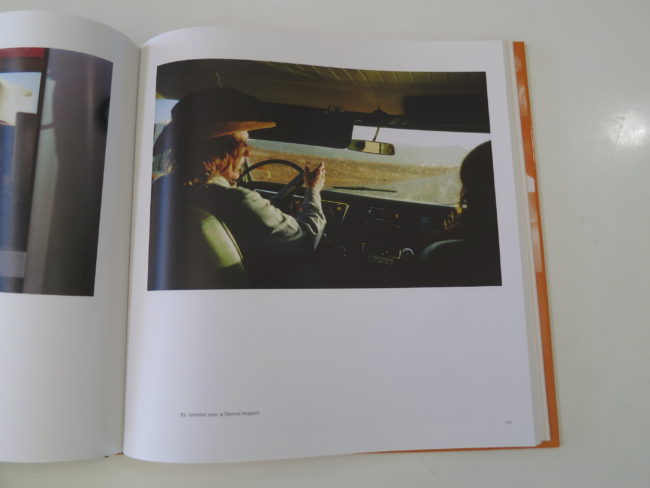

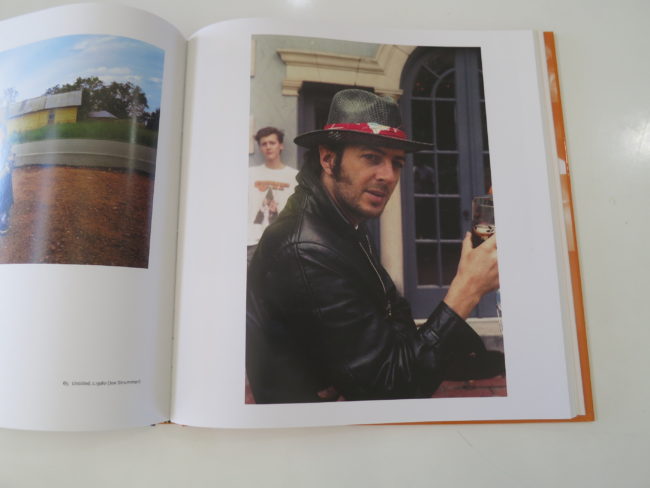

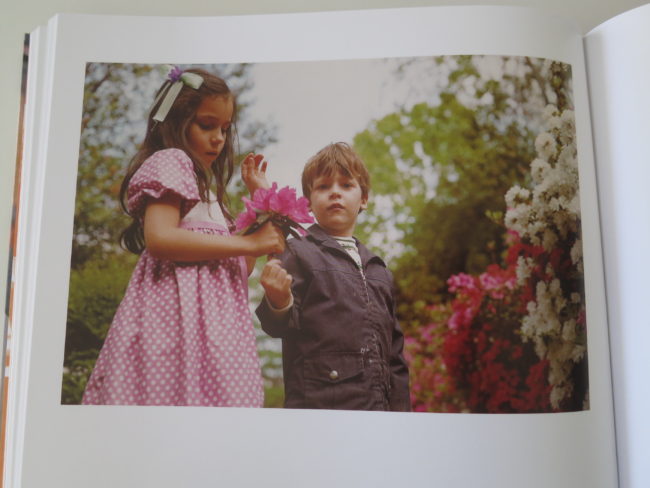

Once he shifts to color, the work takes off, but the book still has a continuity problem. We see several of his seminal images, which are inter-mixed with portraits of his family, and pictures of famous people. (What I wouldn’t give to have sat in the back seat as he shot a peak-talent Dennis Hopper, in the early 70s, on the very same road I drove through Taos last night.)

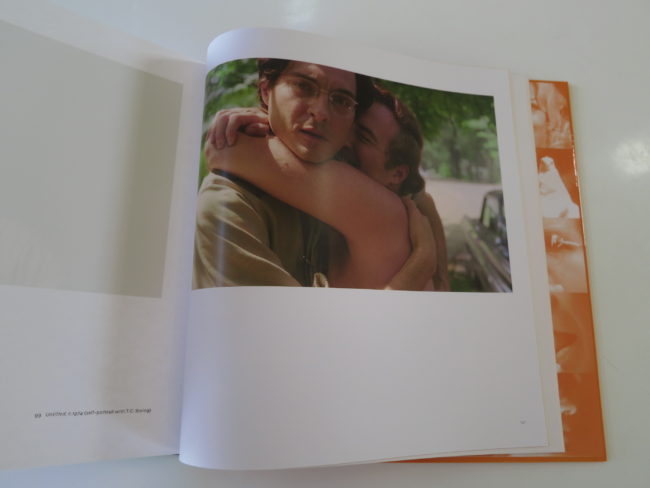

The portraits, and several proto-selfies, are all strong of course, and it wouldn’t be complete without Eggleston naked in a red room, his penis hanging out for all to see. (I said red room. Not red rum.)

The exhibition was organized by the NPG, which is a terrific museum. I saw a cool Man Ray portrait show there a few years ago, which I reviewed here, and recall having a similar problem.

When you decontextualize an artist’s work, you break the narrative that projects create. Pictures are designed to go together so themes can emerge, and symbols repeat. I spent 10 freaking minutes analyzing his use of Coca-Cola Red at Pier 24 in May, because I was so interested in how he had achieved this kind of greatness.

But here, for the sake of an exhibition-constructed narrative, the spell was broken. All fine pictures, yes. But they didn’t take my breath away, despite Sofia Coppola’s implicit promise that they would. (She wrote a brief introduction.)

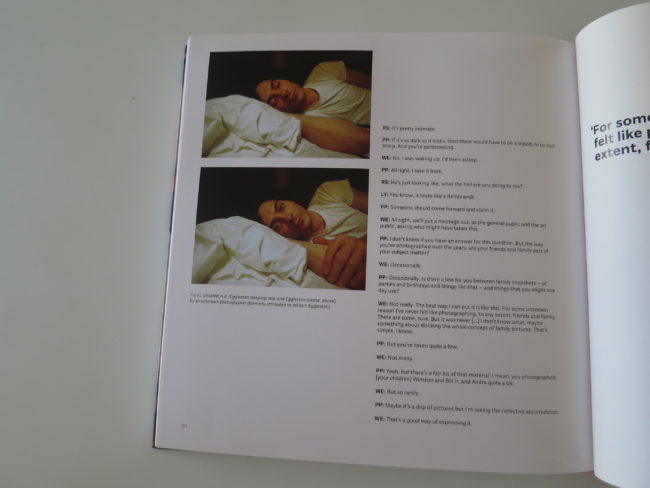

I’d guess most people would still want this book, as it brings together a chunk of excellent photographs, while giving you a glimpse into the artist’s private life. In 2016, no one can seem to get enough of the backstory. (It includes an extensive Q&A with the artist as well.)

But it reminded me that sometimes, when you’re looking at perfect light on your daughter’s cheek, or a day-dream happy expression in your wife’s eyes, you need to fight off the urge to take a picture.

Just enjoy, until the moment is gone.

Bottom Line: Fascinating yet flawed look at Eggleston’s portraits

To Purchase “William Eggleston: Portraits” Visit the National Portrait Gallery in London

3 Comments

[i really like Eggleston (although, truth be told, I do believe Saul Leiter blows him out of the water, color OR B&W).]

Earlier today, people were yakking about the “harvest moon”, so I recommended a photo location up on Sunset Blvd in Hollywood facing due east and people said, “GO, go, take a picture,” to which my reply was, “Well, no, you go.” I’ve already SEEN it.

That was then, this is now. ‘Now’ is yours alone.

Seems they’ll be digging out “new” Eggleston finds and retreads for the remainder of my life; and as you stated, the B&W are quite good indeed, but it’s the color he’ll be (justifiably) remembered for.

PS- Get yourself a GR- pocketable like a phone, impressive image quality.

A lot of the bws look like Frank. The others look like Evans. He was clearly under the influence until he broke through with color and had the confidence and courage to finally give into his most spontaneous, formalist nature. There’s nothing wrong with that. I like seeing the road back.

Comments are closed for this article!