Avani Rai

Director Avani Rai:

Raghu Rai, An Unframed Portrait

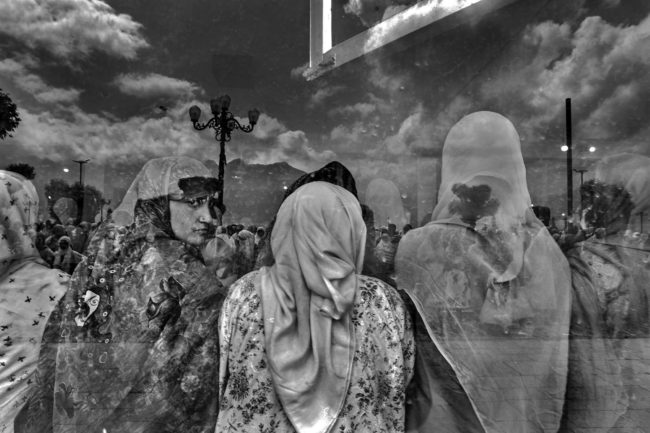

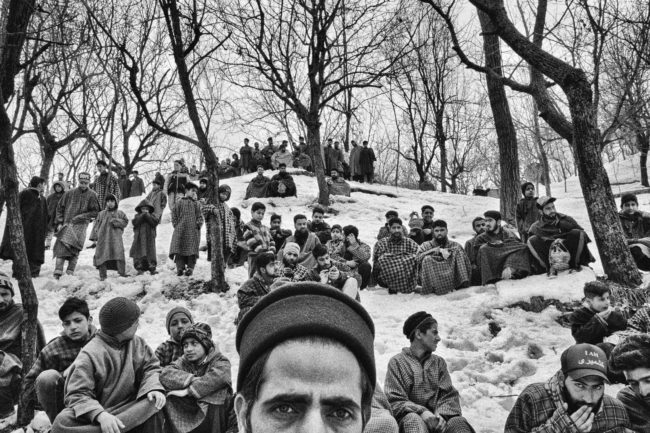

Heidi: Your father mentions that Kashmir is India’s open wound, is that what drew you to that area?

Avani: I have been traveling to Kashmir with my father during the making of the film. All my life I have seen my fathers images and made sense of the world and our history but Kashmir became my first hand experience. Something I had never had. After the film was completed, I stayed on in Kashmir and over time, Kashmir and the people of Kashmir became very close to my heart. That is why I keep going back (and that is why I am sharing a few images from Kashmir)

You mentioned you had to be a filmmaker and not a daughter during the creation of Your 55 minute documentary Raghu Rai, An Unframed Portrait. When you look at your father’s work, are you viewing as a daughter, as a photographer, do those roles blend for you?

The film is about that conflict. Me as a daughter and a photographer, and him as the father or the photographer. During the making of the film I faced many challenges. There were times where id feel that my father wanted to give me all the knowledge in the past 50 years – keeping in mind his likes as well as his dislikes. At the same time he also wanted me to be my own person. There were times that I walked into his space like a daughter and expected answers from a photographer. That never worked. But when I look at his work, which is also the photo history of our times – I view it only as a photographer. That is my responsibility. I learnt to do that over the 7 years I observed my father through my viewfinder. It was a process.

As time has passed can you flow more easily between daughter and artist?

The film made me realize many things. our conversations no longer ended in an argument. There is respect between the two of us and dignity in our differences. I can now go back home to my parents and feel like a daughter without as much pressure I would have everytime he came in front of me to pick up my camera and shoot.

Do you remember when you first understood your father’s body of work and the impact of those photos? Tell us about that.

Even after making the film I don’t think I have seen his complete body of work. But it’s all a process. Images that are timeless have something new for you to understand every time one views them. The first few photographs that I saw of my father was of the buried child in Bhopal.

Tell us about the ending image to your documentary.

That photograph (at the end of the film) was taken a couple of months before I finished filming. It just came to me. It wasn’t planned but when I did take that – I knew how my film was going to end after 6 years of trying to make it. This was taken in the Delhi at the river during winter. The bird in the image is a migratory bird that only comes during that season.

How did you creatively blossom after the making of this film?

I felt like I had a clean slate. I had said what I had to about my lineage and I could start all over without being judged. It opened my mind, it cleared a lot of things. I knew better what I liked and disliked, where my father and I were similar and different and we started to respect that. (please watch my film soon J

What kind of gravity comes with being Raghu Rai’s daughter? Is it internal, external?

I started to make the film because of this identity crisis. I often fought with my father when I didn’t like something, but I didn’t always know what I did like. It took time and effort as I worked on the film – to get to know myself better. And when I feel I do – I don’t need to prove to anyone anymore. It’s a good feeling.

I made this film because I love my father deeply but I didn’t understand him enough. After I made it – I love him even more and I am happy to be me. Whoever knew me knew me for being his daughter. But after making this film and through the years they acknowledge my work and that is a blessing.

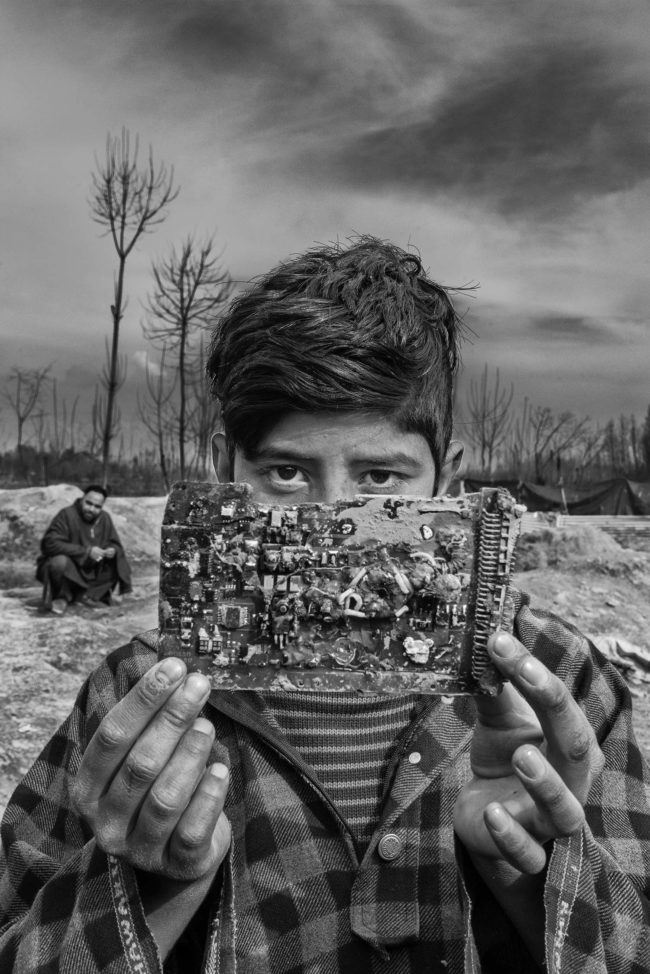

In your debut show: Ground Zero what questions of the heart were you trying to answer?

I am still working on the project. I feel like it’s a never ending project. I try to answer questions of stereotypes, the ideas of Kashmir (as the Indian media reports it) and the women and children of a conflict state which is also the most militarized land on earth.

Congratulations on your Getty Reportage inclusion. Is that image from Ground Zero and all done in camera?

Thank you! Yes.

What are your thoughts on how being a woman behind the camera opened up different emotions from your subject… do you feel it would have been different if you were a man?

There are places where women aren’t allowed and there are places where men aren’t allowed. Being a woman – I was able to walk into the lives of the people I want to connect with – my current project being on women and children. If I were a man I would probably not be able to do that in a Muslim state (Kashmir) especially, at least not so easily. For most of history woman photographers were fewer than men- I don’t like this idea. It is very important to view the world from a woman’s perspective. Men documenting the world can never be a wholesome experience when you haven’t seen a woman’s.

1 Comment

Great conversation with awesome pictures. Kudos to Avani for painstaking work in Kashmir.

Comments are closed for this article!