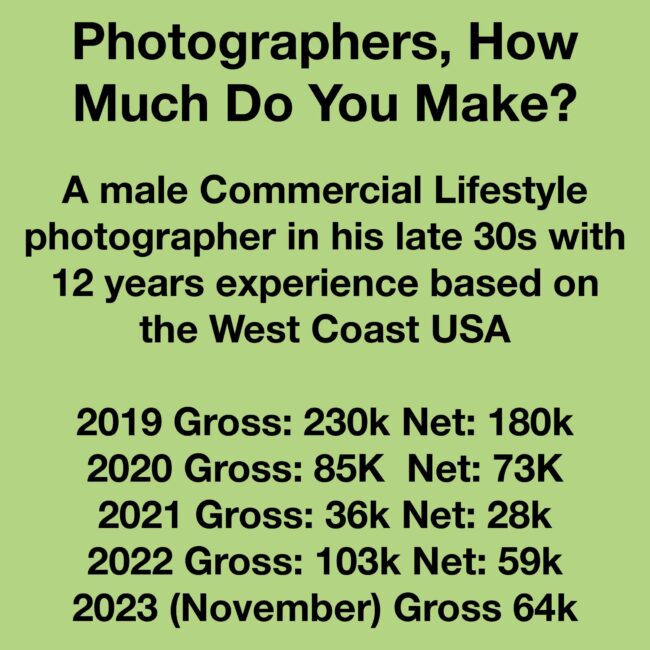

In the years leading up to the pandemic, my gross income ranged from $115,000 to $230,000. Keep in mind, that this number is after my reps took their 30% cut, so the actual gross was higher. I became a full-time photographer around 2011. In those initial years, when I was solely focused on photography and not supplementing with assisting work, I was pulling in roughly $70,000 to $85,000 gross and steadily built my way up.

After college, I spent about four years as an intern, film production assistant, and photography assistant. To support myself during that time, I also worked at a supermarket.

I don’t currently have an agent, but I do work with one on a case-by-case basis if a project that comes in is substantial enough to warrant their involvement. In the past, I’ve been signed by three different agencies. One was a boutique agency, another was more mid-range, and the third was a well-known and prestigious agency. Each of these experiences was incredibly different from one another.

A couple of years ago, I decided to part ways with my last rep, and since then, I’ve been on the lookout for a new one, but it’s been a bit of a challenge finding the right fit for both parties. I have to admit, ego aside, that it’s been surprising how tough it’s been for an established commercial photographer, with over a decade of profitability, to even secure a meeting or a response from many agents.

Approximately 90% of my income is generated through commercial lifestyle projects. Editorial assignments have generally come my way only about two to three times a year.

In terms of workload, I typically handle bidding anywhere from 25 to 40 commercial project requests annually. During a successful year, I manage to secure around 5 to 7 of these projects, although it’s worth noting that there are no guarantees any year.

Most projects involve three, but up to six or more photographers bidding for them. There can be additional challenges like budget and scheduling problems that might lead to the project being canceled or postponed indefinitely. Even if you and the agency’s creative teams are on the same page, the final decision typically rests with the client. This client is usually someone you haven’t spoken to, and they often aren’t focused on creativity; they’re on the business side of things and have the ultimate say because they’re footing the bill.

I mainly work with Fortune 500 companies. I’ve collaborated with big advertising agencies and shot over two dozen global and national ad campaigns and also directed several TV commercials. My clients range from top tech companies and big sneaker brands to car ads, alcohol, healthcare, tourism, and pharmaceuticals.

I initially started with smaller “cool” brands, which eventually led to bigger projects. I still try to take on creatively interesting projects each year, even if the budget is tight.

I don’t have any employees that are on payroll. I hire assistants and techs on a freelance basis as well as professional services such as my accountant etc.

I keep my expenses low to survive in lean times. However, living costs have gone up significantly in recent years, while job opportunities and rates have not. I have substantial expenses like self-employment taxes, photography insurance, and health insurance. On top of that, I’ve managed to pay off my student loans, which were quite significant.

I work from my home office, which I can deduct as a business expense. I own just the essential equipment I need for smaller personal and editorial projects so I can work on them on without needing to rent extra gear.

I’ve never had a great retirement plan, just been trying to save up as much as I can and put a bit into an IRA. But these last couple of years, work’s been slow, and it’s taken a toll on my savings. If I decided to retire right now, I could probably get by for about two years in a more budget-friendly city without needing to work.

I’m pretty much “working” in some way every single day. In peak years, I used to work on a commercial project roughly every other month. These gigs could vary from quick 2-3 day shoots to those massive weeks-long projects that involved jetting off to different countries. Typically, each project would come with a couple weeks of prepro work and another couple weeks for post-production.

These days, it seems like most of my time is eaten up by bidding on projects, marketing my work, and all the research and outreach that goes into it. I also try to set up test shoots every couple of months and work on personal projects whenever I can.

Before the pandemic hit, my income was somewhat stable. There were some tougher years, but overall, I felt like my career was steadily growing and building each year.

In 2020, I got lucky because the year started well, and I managed to weather the storm with some government help.

Then came 2021, which turned out to be the kind of year every photographer dreads. I didn’t land a single profitable job. I was bidding on some good and high-paying creative projects, but none of them went my way. I did a few smaller shoots and personal projects, but they barely made any profit. My income mostly came from licensing images, government subsidies, and selling off old cameras and equipment. It was a really tough and eye-opening experience.

In 2022, things improved somewhat, but it still felt like the twilight zone.

Now, in 2023, it’s been more of a mixed bag. I’m getting more inquiries than in the past couple of years, but not a lot of success. It’s been one of the most frustrating years in my career, for sure, and is looking to not be a great one financially.

Photography is my sole source of income. In the last couple of years, I’ve really made a big push to find more stable work within the industry. I have been searching and applying for jobs that come with benefits, like 401(k)s, health insurance, stuff like in-house production or photo directing/editing jobs for big companies. But it turns out, those positions are just as competitive and hard to get into as being a freelance photographer.

There isn’t really a standard for an average shoot because projects vary quite a bit. Typically, a commercial shoot involves a tech day, two to three shoot days, and perhaps a post-production day. The day rate usually falls in the range of $2,500 to $7,500, and then usage fees are added on top of that. The usage fees are typically based on geographic terms and the duration of use. All in, I would ideally hope to take home between $20 – 30k per project, but it varies greatly. The best shoots have been the ones where it feels like the creative team is all in, and the terms are fair for everyone. I’ve come to realize that a good pricing strategy involves having a lower day rate, but with a usage agreement that’s likely to get renewed after the initial period. It also motivates me as a photographer to create images that are unique to the brand and will likely be renewed and won’t be easily replaced by stock photos.

I pay my assistants whatever rate they ask for. I think the going rate for a first in LA / NYC is about $700 – 800 for a 10 hour day. I will always go to bat for my assistants, they are the hardest working and most important people on a job in my opinion and I want them to feel comfortable and well compensated for their work.

The worst shoots have been the ones where they insist on a full buyout. Lately, I’ve noticed a troubling trend where art buyers require all bidding photographers to accept a buyout or else they won’t even be considered for the job. It’s like being turned into a content-producing machine for a big corporation. They walk away with thousands and thousands of your images that can be used indefinitely. This isn’t a fair or ethical way to work with commissioned artists, and the more considerate art buyers are aware of this issue and don’t abide by it.

I do both motion directing and still photography. My projects vary – sometimes I’m both directing and taking photos, other times I’m focused on shooting b-roll videos for social media. Occasionally, I work as a photographer alongside a broadcast film team. I’d say that in the past few years, about 75 percent of my shoots have had some motion element involved.

My marketing strategy has gone through significant changes in recent years. I can still recall a time when sending a single email blast would result in a dozen job offers. Over the years, I’ve also sent out hundreds of promo materials and made many in-person portfolio visits. However, the landscape shifted during the shutdown, and to be completely honest, I’m not sure what’s effective anymore. I do believe having a social media presence is beneficial, but it shouldn’t be the sole focus. Most of the jobs I’ve secured in the past couple of years have come through word of mouth – someone I’ve worked with in the past recommending me to others.

The best advice I’ve ever received is to “make photos that only YOU can make.” There are literally billions of photographers out there, and photography is a highly mechanized process, so you see countless people trying to imitate others or reproduce what they’ve seen before. With the rise of AI, this imitation problem is getting worse. When someone hires you, they’re not looking for a copycat (hopefully!); they want your unique perspective. Regardless of the subject, make it something that resonates with your personal view of the world and it will connect with others.

As for the worst advice, I’d say it came from my younger, more naive self. When I was younger, I thought I understood the industry better than I actually did. I didn’t think long-term and, like many artists, my ego sometimes clouded my judgment, especially during hot streaks that I believed would last forever. Being overly confident is great for creativity and taking risks, but it might not be the best approach when it comes to the business side or navigating industry politics.

I’m also a clinically diagnosed neurodivergent individual. While I don’t use my disability as an excuse or ever share this with potential clients, it has added significant challenges to my career in various ways.

This piece of advice is for those in gatekeeping positions in the industry, such as art buyers, photo editors, and producers. Let’s remember that kindness and compassion are choices we can all make. The culture in our industry can be demanding, cutthroat, often quite cynical, and plagued with cronyism and nepotism. We’re all out here doing our best, hustling to survive in this late-capitalist world.

Yes, we photographers are incredibly privileged to make a living through our work, but it’s a career that many of us have put a lot of effort into. And at the end of the day, it is a job. So, let’s not make it feel like we have to beg and bend over backwards for opportunities to do what we love and what also we depend on to keep the lights on and our families fed.

Unfortunately, there are no unions or standardized practices to adhere to in this industry. That means the gatekeepers hold a lot of power and control.

Please don’t forget the human aspect of your roles. We often problem-solve the budget on your projects, contribute to your creative vision, get on last-minute calls, and reschedule our lives completely, all of this is without any sort of compensation. Sometimes, a simple email response or a courteous notification when a project doesn’t work out is all that’s required, instead of ghosting someone and keeping them in a state of anxiety.

As many have pointed out, while photographers can show solidarity, there will always be someone willing to work for less – that’s the nature of capitalism in a creative field. So, photographers, we also have a responsibility to ourselves and each other to shape the way the industry treats us and those who collaborate with us.

So please…be excellent to each other.