I do a lot of consulting these days.

It’s become the primary way I make a living, (along with writing,) though I certainly never planned it that way.

In a perma-freelance, side-hustle, gig-economy world, creative types do what we must.

(If it works, it works.)

I walked away from my long-term, adjunct teaching job in 2017, as the salary UNM-Taos offered me, in my last contract, was so bad I couldn’t justify the time commitment.

I remember thinking, so clearly, if I couldn’t generate more money than that, working for myself, I should probably find another career.

My first move was to found our Antidote Photo Retreat program, and it certainly grew, and was on an upward trajectory the first three years of its existence.

Then Covid hit, and having people come stay on my property, eat in my kitchen, and shower in my bathroom, was neither safe, nor practical.

(Shout out to Cliff Claven.)

In those first years, I did a small amount of consulting, trying to help people one-on-one, but certainly didn’t promote myself that way, and was still figuring out how to be an effective advocate for my clients/students.

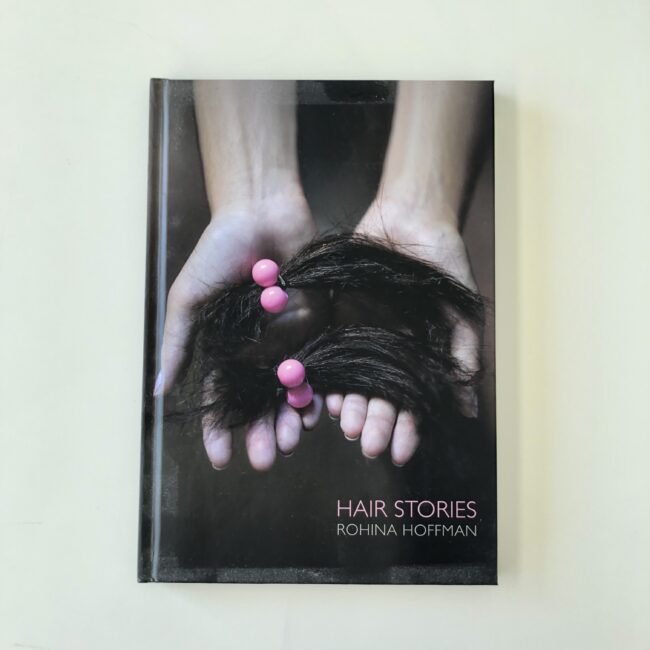

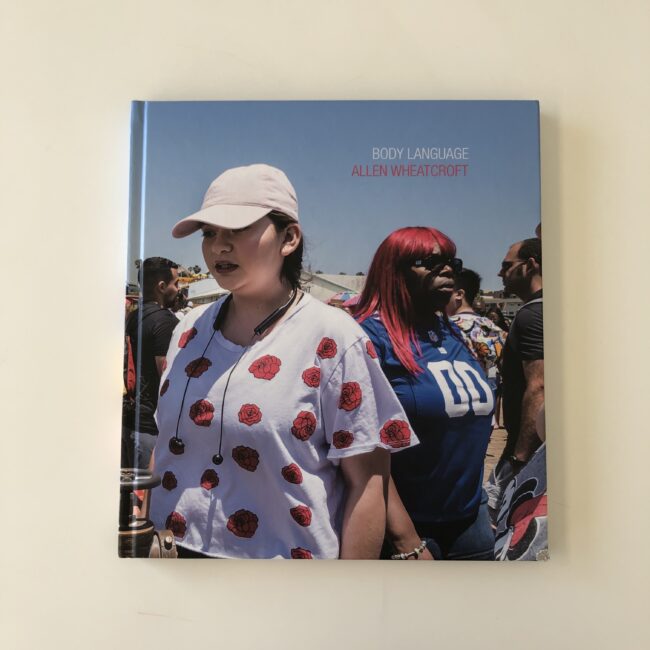

Private teaching was rewarding, and I helped Rohina Hoffman and Allen Wheatcroft produce photo-books with Damiani, but again, I was definitely figuring things out.

After the pandemic began, I transitioned my Antidote program online, and offered free evening critique classes to my community, before ultimately charging them a nominal amount when it became clear there would be no retreats.

Zoom made in-depth, online teaching possible, and if I’m being honest, the amount of personal growth I endured, due to stress and trauma, has made me a better person, and a better teacher, so more work came my way, and I was able to raise my rates, bit by bit.

I can see how the process evolved, in retrospect, but I’m not surprised how much of the work has centered on one particular area:

Helping people conceive and produce photo-books.

Because everyone wants a book these days, and you likely know I made my first book, “Extinction Party” in 2020, which was released on the cusp of the global lockdown, and was very well-received by the press, and the people who bought it.

(Of course, we weren’t able to market it at art and book fairs, as they all shut.)

So today, I thought it might be a good idea to give you a primer on how the process works, because if I can do it for my clients, I should be able to share some of that info with you, my loyal audience.

Here we go.

If I were to break it down, the process would look something like this:

Vision

Concept

Structure

Edit

Sequence

Design*

Text*

Refinement

.pdf

Publisher

Printing

Release

Marketing/Publicity

*Sometimes, the text comes before the design, it just depends.

Now, that’s how I work with my design partner, Caleb Cain Marcus, as he’s an acquisitions editor at Damiani, so we know they’ll look at the books we create.

In our case, we make the book, then find the publisher.

(I’ve got a network of contacts in the publishing world, so once the digital version of our books are done, we know we’ll get eyes on them within the industry.)

Back in the day, I think they called this process “book packaging,” but I just call myself a producer.

Not everyone needs outside help, of course, and some publishers do like to work on a book from start to finish, though those tend to be more indie, small-batch types, which is also a valid way to go.

Honestly, there is so much to unpack, I’ll do my best to keep it coherent.

At a photo festival in 2010, I met the great English publisher Dewi Lewis, whom I interviewed for the blog five years later, and he gave me some amazing advice, which I took to heart.

He said every artist seemed to want or expect a book for each project, compared to the “old days,” when one or two books in a career would have been an achievement.

Dewi recommended an artist wait until there was a compelling reason, and a clear vision, before making a book.

(Don’t do it just to do it.)

Things have only gotten crazier since then, as the amount of publishers has proliferated, as has the interest in photo-books, as the recent Clement Chéroux article in Aperture confirms.

However, in my experience, having spoken to publishers, (and listened to them on panel talks), the demand for photo-books, from the collector class, has not grown in concert with the supply, so very few photo-books actually sell well, and create profit for the publishers.

(Unless you’re already a famous art star.)

So how does one explain that supply/demand disconnect?

What I’ve learned, and am sharing here, is the industry no longer functions in a purely capitalistic sense, with respect to sales.

Rather, some publishers do it as passion projects, not expecting to really make money, or more likely, they build profit into the production system, marking up the printing costs, design costs, and things like that.

(They also make money when the artist “buys” additional copies of his/her book back from the publisher.)

One publisher, whom I won’t name, (out of respect,) is well-known for throwing book deals out there like crazy, sometimes without knowing or meeting the artist, because it’s their business model to make money on production, rather than sales, so the more books they take to market, the better they do.

Why does every artist want to participate in this process, if they’re not likely to “make money” off the sale of their book?

Good question.

Glad you asked.

Over the years, every photographer I interviewed considered his/her book to be a marketing object, and I never met one who said it wasn’t worth it.

Sending out books, giving them away as gifts, and asking your network to support you in the pre-sale or crowdfunding effort, means ultimately, a viewer will look at your work, and understand it, the way you want them to.

A book allows you to control the narrative surrounding your career.

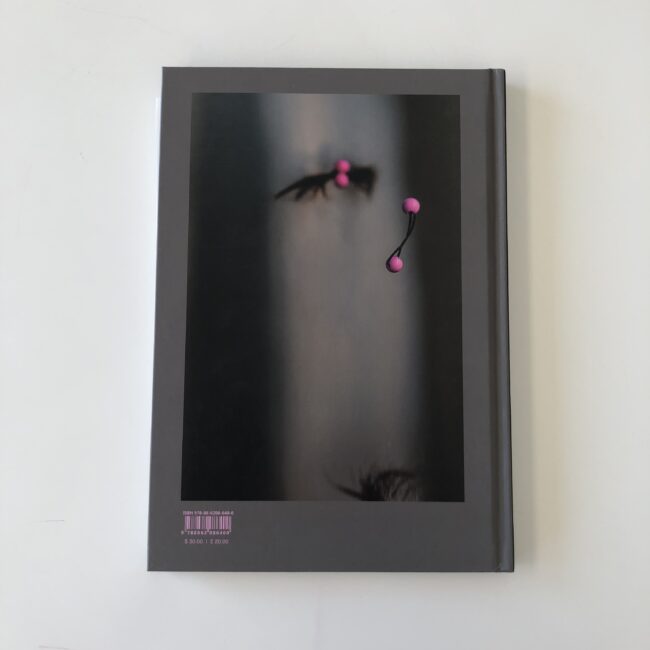

And as I reported in an interview with MACK publisher Michael Mack, back in 2012, books have the potential to be art objects.

Meaning, if you create a great book, you can make a piece of art distinct from the photographs that live inside it.

(One benefit of doing this for so long is I’ve picked up great advice and knowledge, which I then pass along to you.)

As artists, if we view making a book as an “art project,” one that also functions as a high-end marketing tool, it will allow an audience to see what you’ve accomplished exactly as you’d like them to.

It’s a very valuable outcome.

The book can create new opportunities, and help you level up in your career.

You might not make money selling books, (at least nothing major,) but you CAN benefit from more jobs, opportunities, and relationships going forward.

Plus, crowdfunding and pre-sales, which are now so common, allow the artist to defray the costs, so even if books are increasingly expensive, you may not have to reach into your own pocket to pay for it.

(If you’re willing to put in the time and effort to raise the funding.)

With me so far?

There is a pretty wide range of costs, with respect to how you can produce your book.

(And all the numbers I’m going to share are approximate.)

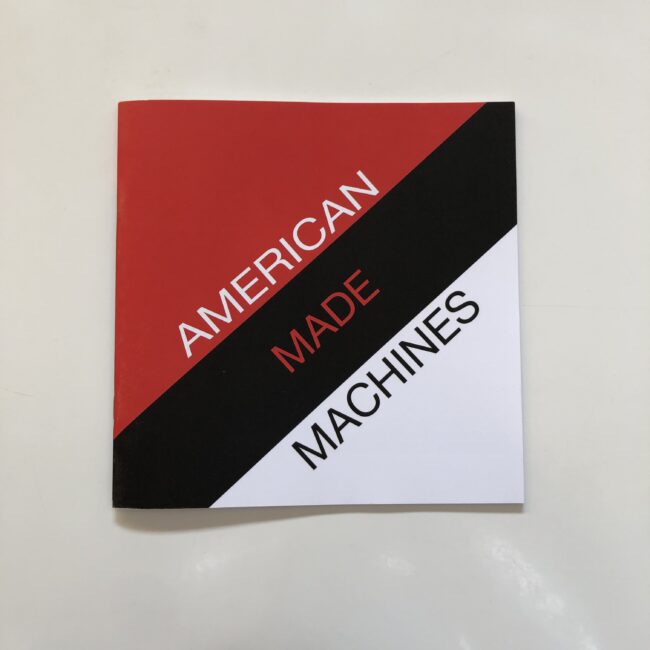

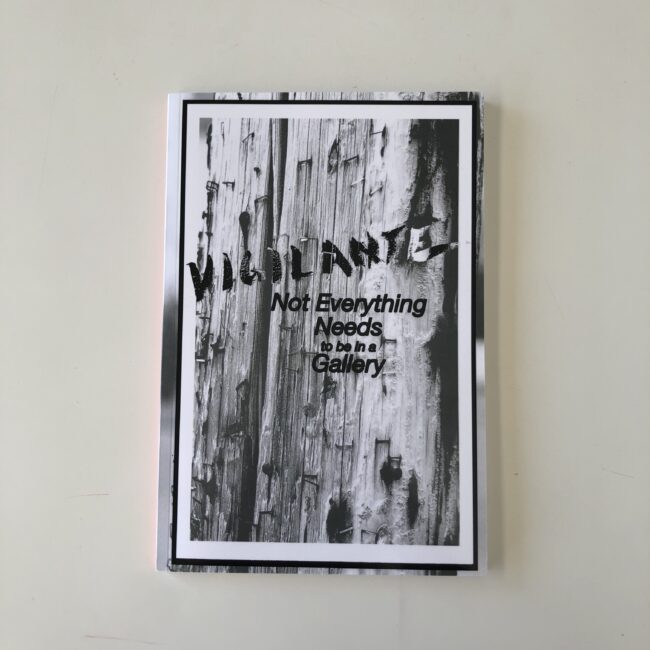

On the low end, DIY ‘Zines can be made for next to nothing, but you have to really know what you’re doing to get the production values high enough to make a positive impression.

It can be done for a budget in the hundreds of dollars, which is a huge advantage.

Next, we’d move on to self-produced, soft-cover, print-on-demand, (or digitally printed) exhibition-catalogue-type-offerings.

Those might cost in the high hundreds, or low-thousands, and can be helpful, but are normally seen as low-cost marketing objects by the people who look at them, I find.

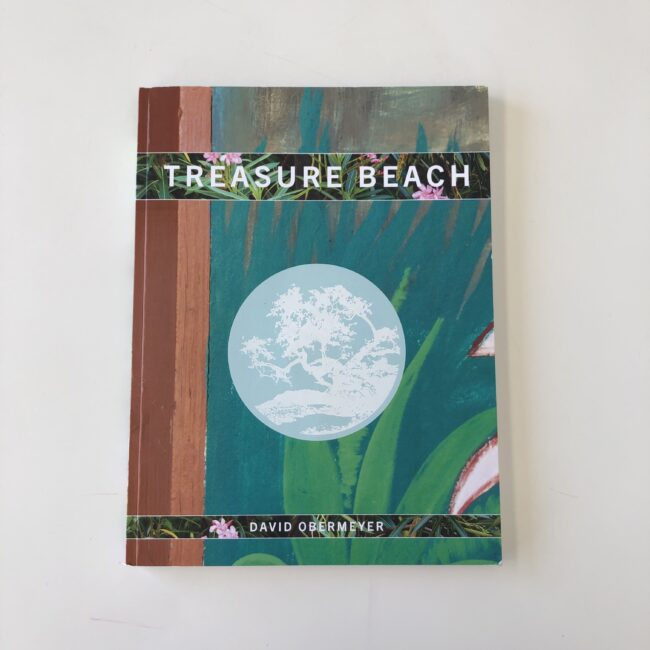

If you hire a designer to help you, and go the high-quality digital printing, or offset printing route, you’re probably more in the $2000-5000 range, but getting professional help makes a difference.

(As a producer, I tell people the best books almost always have a designer’s fingerprints on them, somewhere along the line.)

The smallest run of soft-cover, offset printing of 400 books or so, in Europe, will likely be $7000-9000, though prices are rising with inflation, and tack on a bit more if you go the hard-cover route.

(That’s if you’re self-publishing, but having it professionally printed.)

Finally, we have the costs associated with traditional, mainstream publishers, which typically run from $20,000-35,000, with some high-end, prestige publishers charging $50,000 or more.

That’s a lot of cash, under any set of circumstances.

Small batch indie publishers might well cost more in the $10-20,000 range, but again, these are general figures, so there is variance.

(A tiny handful of publishers still cover costs, but there are so few, I wouldn’t count on that as you plow ahead.)

So let me circle back to that advice Dewi Lewis gave me.

He said, to paraphrase, if you’re going to make a book, you better have a damn good reason, a clear vision of what you want to achieve, and strong need to do so.

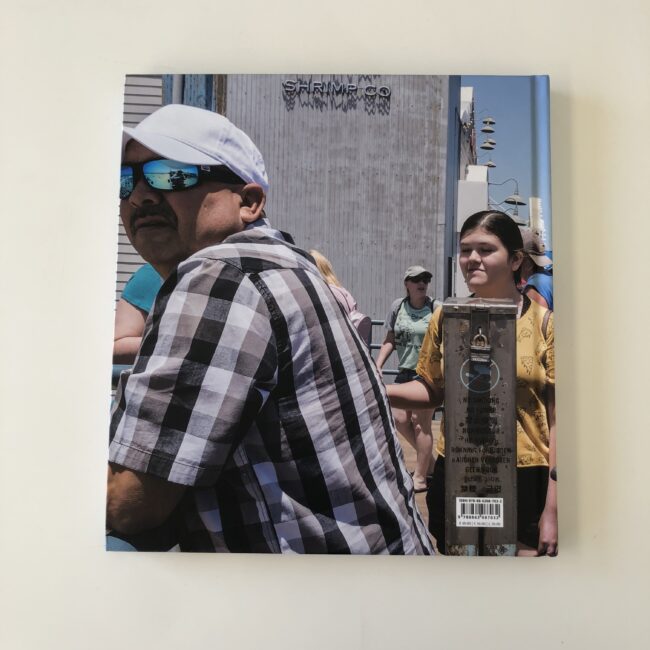

I took that to heart as an artist, and waited 10 years to produce a book that wove together four, interrelated projects into one narrative, so I could show “the world” what I’d been working on out here in the boonies, playing mad scientist in my studio/laboratory.

Even so, I needed my publisher, Jennifer Yoffy, to help me with the initial edit/sequence, and to serve as cheerleader and occasional CEO, over the year it took me and Caleb to make the book.

(As Caleb is my friend and partner, he didn’t charge me for the design, which saved me a bunch of money on the overall process.)

Jennifer and I were also friends, so she didn’t mark up the production costs, and I “only” had to raise about $15,000, instead of twice that.

(That amount included going to the Netherlands to supervise production, which I highly recommend, but isn’t strictly required.)

But enough about money.

I wanted this article to give you a sense of how the industry works, but also how to make a book become a piece of art, representing the best you can achieve.

How do you do that?

It starts with the concept.

What will your book be about?

What will it say?

How will it present your project, (or projects,) in a compelling, interesting, creative, well-executed way?

What will the viewer take away from looking at, (and reading) your book?

I think every great book, as Dewi said, needs a compelling reason to exist, so if you don’t have a great idea, wait a bit longer, or ask yourself all sorts of hard questions until you get the answers.

From there, it’s time to whittle down all the images you have, which could conceivably be included, into a tighter group.

(When in doubt, start with more, but then edit ruthlessly.)

Cut, and cut some more.

Which are the best images?

How do they fit together?

What stories do they tell when they become a group?

What connections, and repeating motifs, begin to show themselves?

Many, if not most artists find it helpful to work with an editor on this, because outside perspective can be key to finding those through-lines, when we’re too close. (Or if we don’t have expertise in the process.)

I do have expertise, but still needed Jennifer’s eye, back in February of 2019.

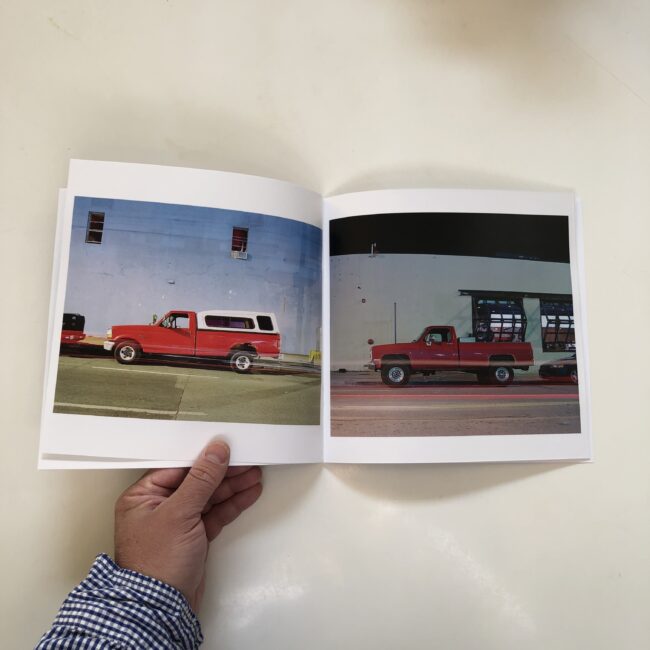

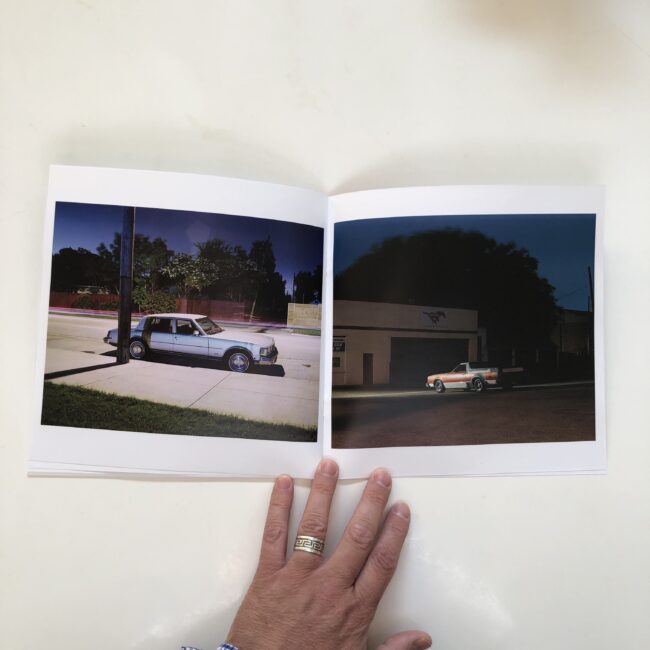

After the edit, the sequence comes next, as building the visual narrative out of your best edit is a separate process.

I like to sequence in Apple’s Photos program, where I can see grids, and move things around easily, but most folks prefer making small prints, and moving them around on the floor.

(Whatever works.)

I’d recommend you keep the classic narrative structure in mind: Beginning, Middle, End.

And I always suggest you consider a viewer’s attention span.

(If they get bored, they’ll start to flip.)

50-60 images is a good target, for a non-coffee-table book, and keeping the viewer surprised, and interested, involves varying the emotional tenor, and offering up the unexpected.

That can mean inter-weaving text, changing image size, or breaking up runs of similar images with something totally different.

There are a lot of ways to skin a cat, but just doing the same thing over and over is a bad idea, unless your pictures are so good, and innovative, that a viewer will be enraptured without any bells and whistles.

(Possible, but unlikely.)

It’s totally cool to think about who will write for the book, and where that writing should be placed, from the jump.

No worries.

But in my experience, often it’s easier once the visual structure has taken shape, and you know more of what the book is, and looks like.

Do you want your voice included in the writing?

If so, what do you want to say?

Either way, at some point, you need to get the text right, because more often than not, text provides context.

Do you want to set up the context at the beginning, so the viewer knows what the book is about, or leave them guessing, and answer questions at the end?

(It’s a personal choice, but a vital one.)

Once it’s all put together, the designer has given you your layout, and it looks like a book, (digitally,) you’ll still need to let it sit.

Come back to it, make some changes, let it sit again, and refine it.

Consider everything.

Paper choice, where you captions will or won’t go, what color end paper, your cover design.

All of it.

Don’t rush.

Patience pays off in the book-making process.

As to finding a publisher, portfolio reviews are great for making relationships.

Festivals too.

And research what type of books the publishers are putting out, to see if your work will fit with their program.

(Fit really matters, as does the working relationship.)

Almost all publishers these days expect the artist to come to the table with the production funds, so have a plan to do that, based upon your budget, and willingness to ask the “crowd.”

Finally, when your book is done, few publishers invest a lot of time or money in marketing and PR, so many artists pay the extra cost to hire PR support on their own.

On the one hand, a publisher might send out bulk emails with a list of books.

(Maybe they’ll have a table at a fair, once those return in earnest.)

But if you’re willing to invest that little bit extra, (or not so little,) you get a PR professional sending out individual emails to press people, and following up.

They work hard to tap up their own networks, and in my experience, that really does matter, when it comes to getting great press placement.

If it all sounds like a well-oiled industry, where people throughout each part of the process are taking their cut, it’s because it is.

But that’s what tends to deliver high production values, wide distribution, and successful marketing campaigns.

This stuff doesn’t come cheap.

Remember, though, earlier in the article, I also discussed how to do this on a super-tight budget.

Books don’t have to be expensive.

For quality, very often though, you get what you pay for.

I swear, I didn’t wake up today planning to drop a 2700-word-treatise on you.

But I did spend an hour last night, pro-bono, explaining the process to a photographer friend I met at FotoFest in 2012.

I figured if he didn’t know how things really work, (and he’s a professional artist and long-time professor,) you might want some extra knowledge too.

Hope it helps!

See you next week!

{ED note, 02.02.22: It’s come to my attention this post is being used as a resource, so I wanted to add one final piece of intel that I tweeted in the viral response to the article. I’m told some artists have been able to create a workable edit/sequence/design book maquette, after taking a book design workshop. Yumi Goto, in Japan, has been recommended to me.}