This might seem like a long story, but bear with me.

Back in the Spring, as I walked across Central Park with Patrice, a gray-robed Chinese monk stepped into my path, reached out, grabbed my hand, and put a wooden-beaded bracelet on it.

He was quick, like a Shaolin monk, before I could think to refuse.

So I said thanks, reached into my pocket and gave him a dollar. I turned to walk away, but in highly broken English, he pointed to his list, and showed me the previous person had given him $20.

I looked at him, he pointed at the list.

I said, “You want more money?”

He nodded yes.

I reached into my pocket, took out 2 more dollars, gave them to him, and then he blessed me. I bowed back, and moved on, not sure exactly how that had come about.

It felt really deep.

Later, downtown, my friend Felt mocked me, saying the whole thing was a scam, but it felt real to me.

Turns out, I wear that bracelet all the time. I’ve really come to like it. And I began to feel bad that I’d only paid $3, as it’s worth more than that to me.

Had I shortchanged a monk?

Isn’t that bad karma?

I swore the next time I saw a monk like that, I’d give him some more money instead, to make sure I was all good with the powers that be.

And sure enough, as I walked towards the lake in Chicago late last month, just up the street from the Art Institute, (with my friend Kyohei in tow,) who do I see but another gray-robed monk with a handful of bracelets.

I show him mine, thank him, and give him a few dollars. Again, like the last time, he asks for more, so I give it to him. But as I don’t need a bracelet, as I’m simply paying into the cause, he gives me a Bodhisattva blessing card that says “Work Smoothly Lifetime Peace.”

Then he bows in blessing, and we’re back about our business.

But since my spiritual moment slowed us down 2 minutes, by the time I got back to that very same spot, (after getting my press ticket,) I bumped into a photographer I knew in Santa Fe, 7 years ago.

I’d recommended she go to Chicago for her MFA, as I’d heard such good things about Columbia College, and she did. We said hello, and once she told me she was now the collection manager in the photo department, I jumped into journalist mode, and asked what the special places were to see?

It was she who gave up the intel on the secret Japanese galleries, and who later arranged to have the photography curator, Elizabeth Siegel, come meet us in the gallery to give us a little talk about Hugh Edwards.

How random, or coincidental, or meant-to-be is that?

Because I stop to give money to a Buddhist monk, because of my Jewish guilt, I get the inside scoop on some amazing Buddhist art inside the museum?

These are the things that keep happening to me when I’m in Chicago, and why I really can’t wait to go back. I’m sure different cities do this for different people. but I’m so comfortable there that I end up talking to everyone.

Inside the gallery in the Hugh Edwards show, (a terrific exhibition inspired by the Art Institute’s legendary former curator,) I started chatting up an African-American security guard.

She admitted she found the show boring, and I asked if it was because there were so many rectangular, black and white pictures in black frames with white matte boards, and she said, “Yeah, that’s it.”

I said I understood, and as my friend and I were both artists and professors, we were able to get excited for all sorts of geeky reasons.

I told her I’d give her one tip, and she could see for herself if it opened anything up about photography.

There is, in the exhibition, an amazing suite of about 10 Robert Frank prints from “The Americans.” (Hugh Edwards was the first curator in America to show the work.)

I told her about my favorite diptych, maybe in the History of Photography: on the left, a fancy car in Los Angeles, covered, shimmering in the fancy light, with the swaying palm trees. On the right, a dead body, covered by a dirty blanket, lying by the wintry side of Route 66 in Arizona.

Two strong pictures, yes, but the context supercharges them.

I said my goodbye, and walked deeper into the show to see work by Eugène Atget, and Duane Michals. There were daguerreotypes in the exhibit, and more.

Kyohei and I ended up talking about the show with an African-American couple around our own age, and some Asian-American schoolgirls.

Random, in-public discussion.

Yet again.

By the time we were ready to leave, the security guard walked up to me and said, “I went and looked at those pictures, and you’re right. That’s powerful right there.”

We all get off on photography, or you wouldn’t be reading this. (Except for you, Mom and Dad.) And when it leads to discussion, to dialogue, to a deeper understanding of the world we inhabit, then I’d argue the art form has done its job well.

So today, I’m glad to share the second batch of work from the the 2017 Filter Photo Festival.

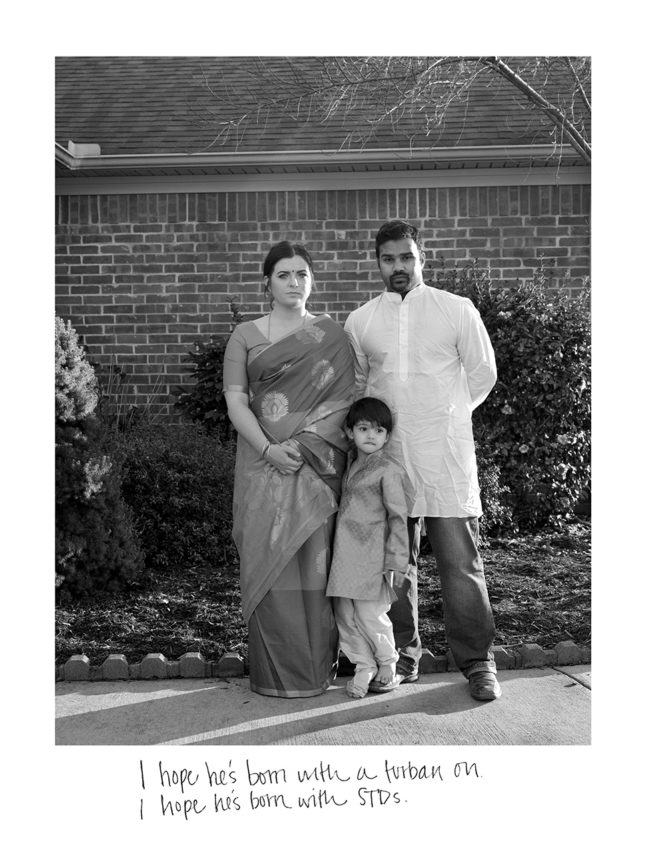

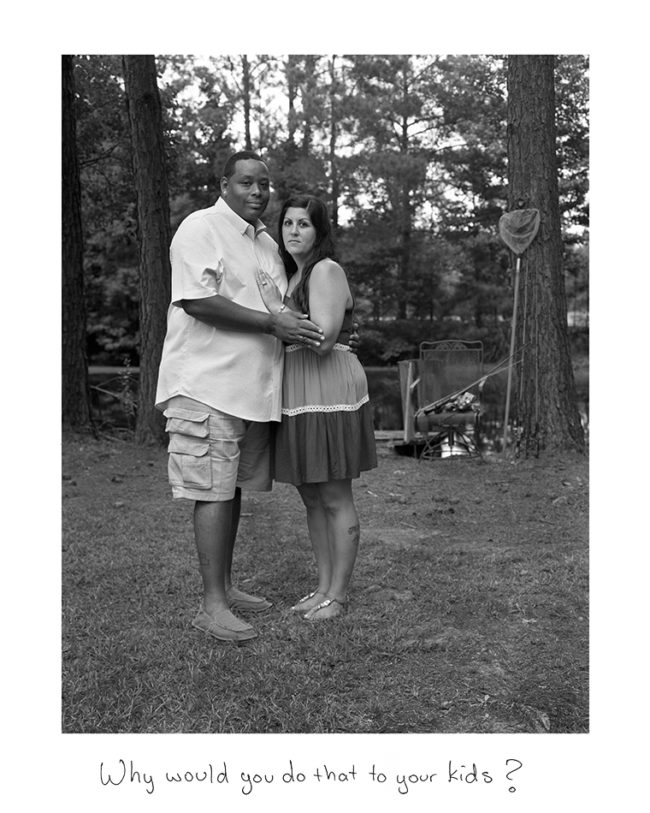

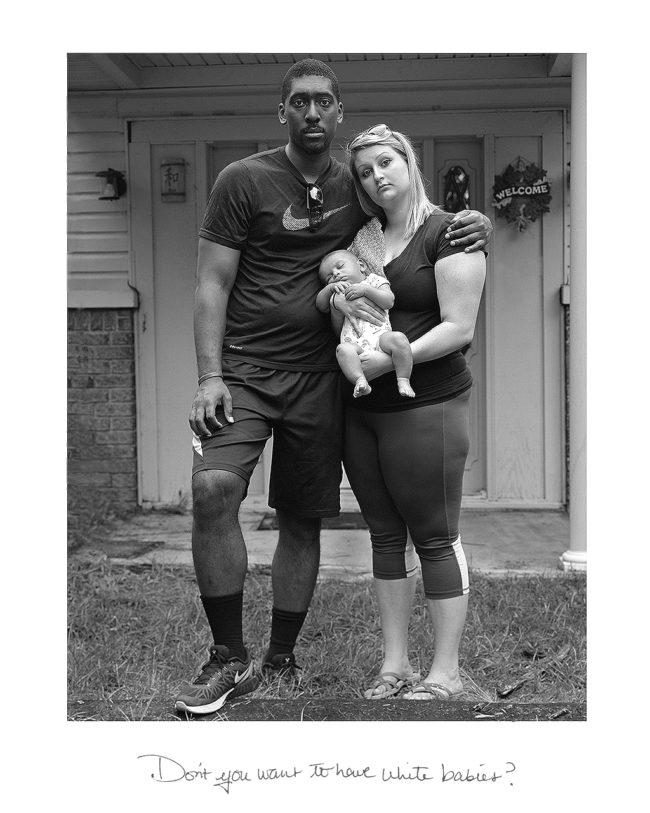

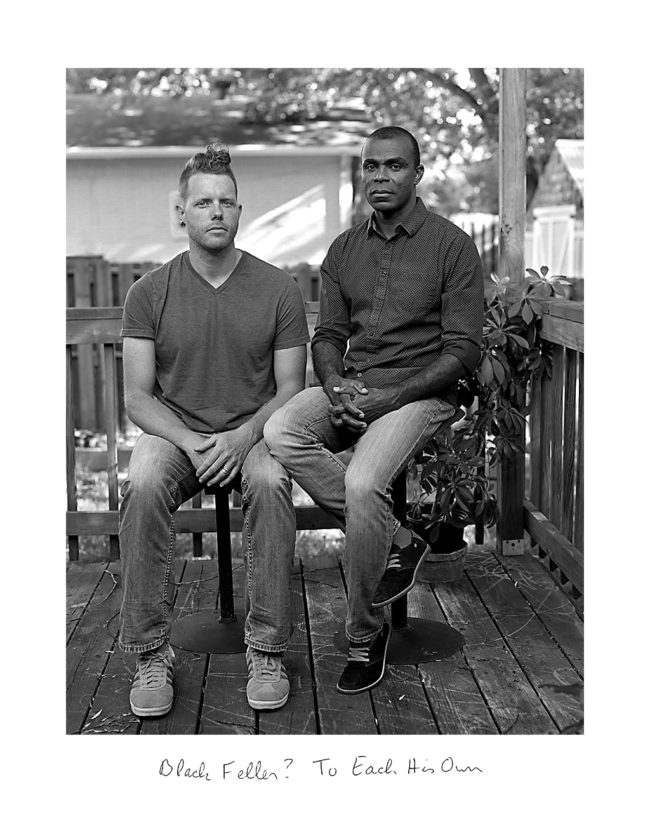

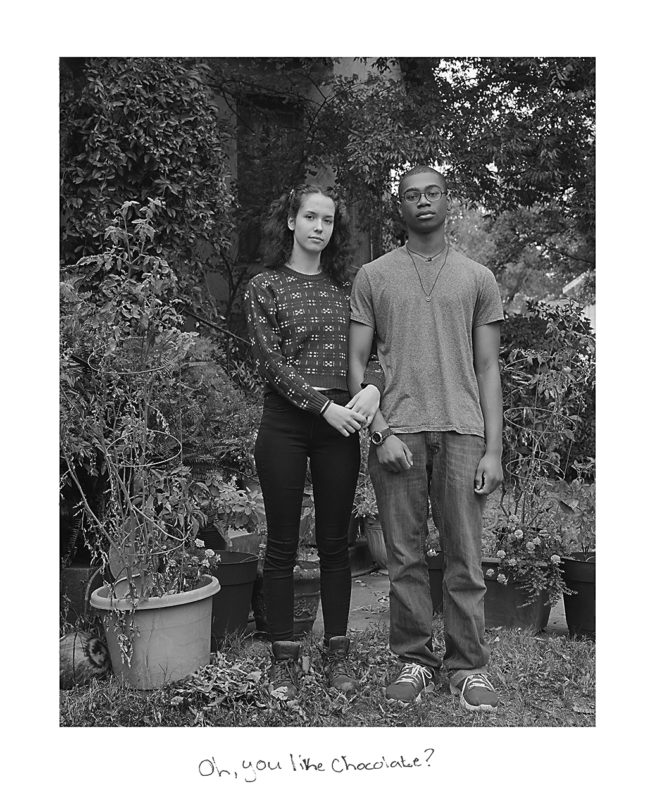

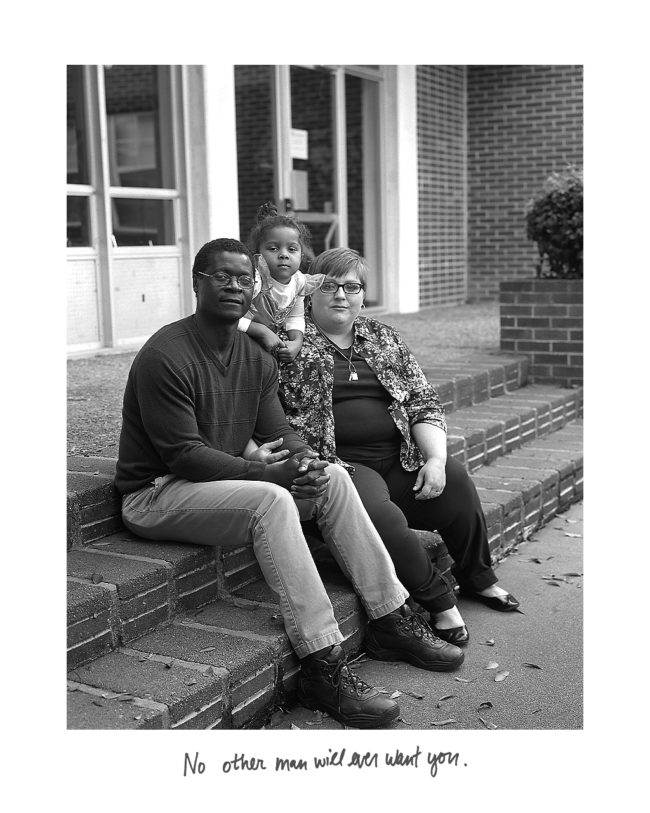

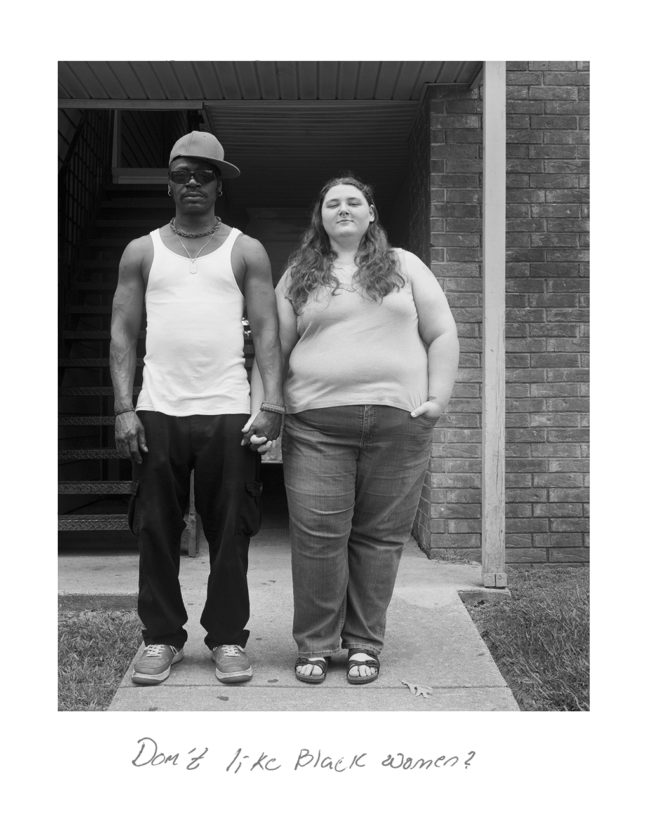

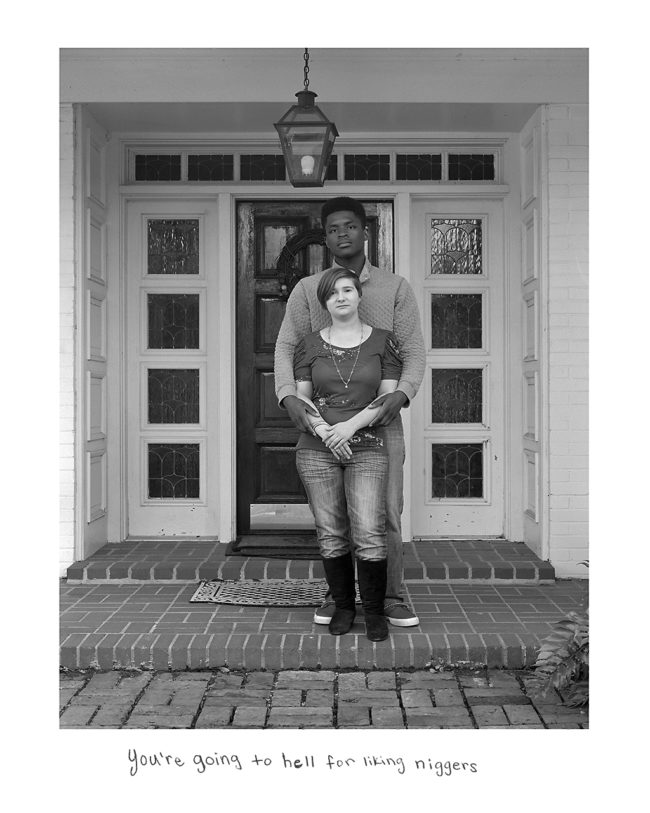

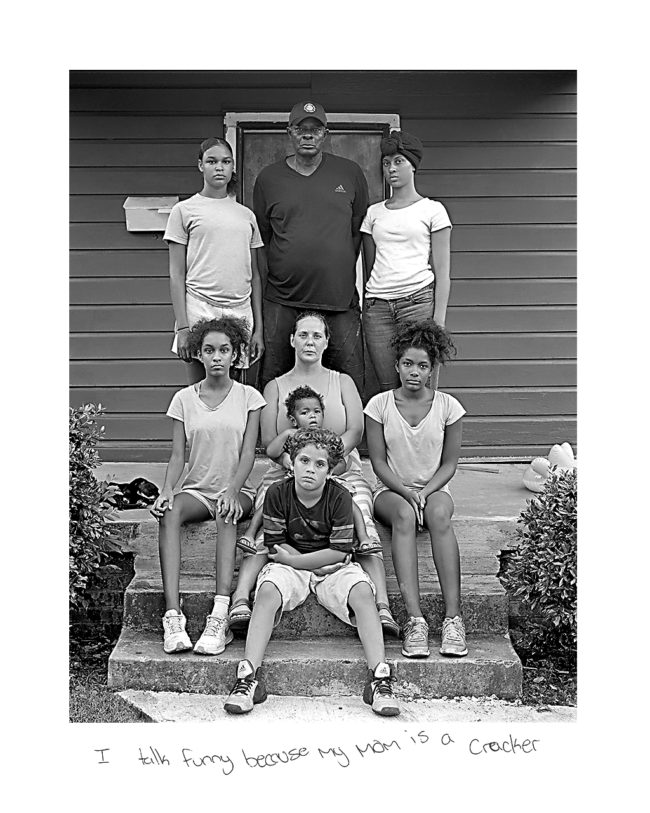

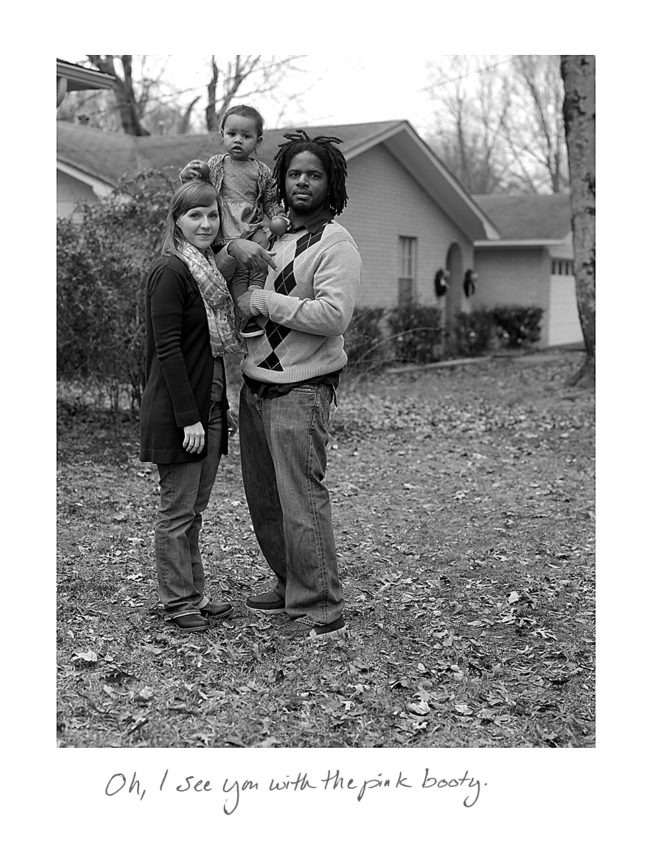

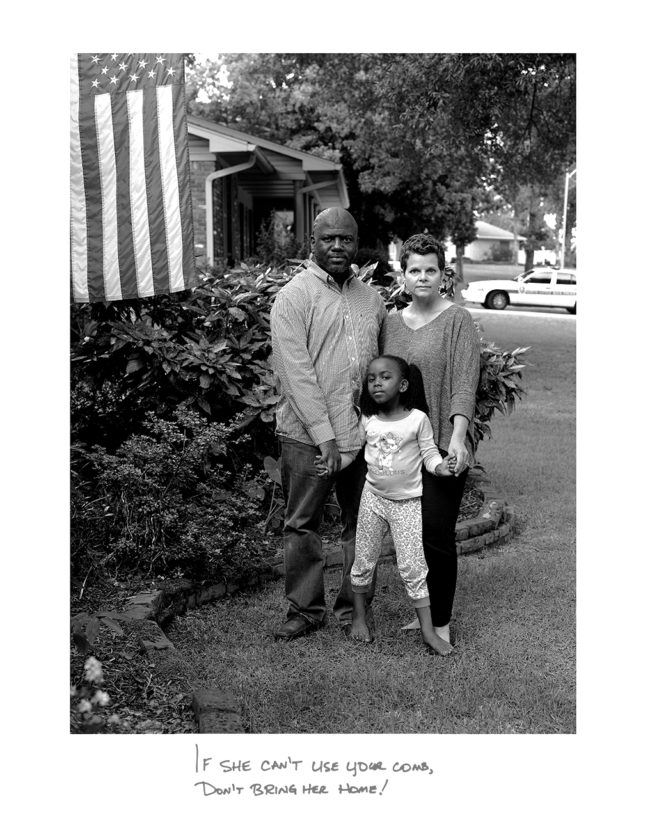

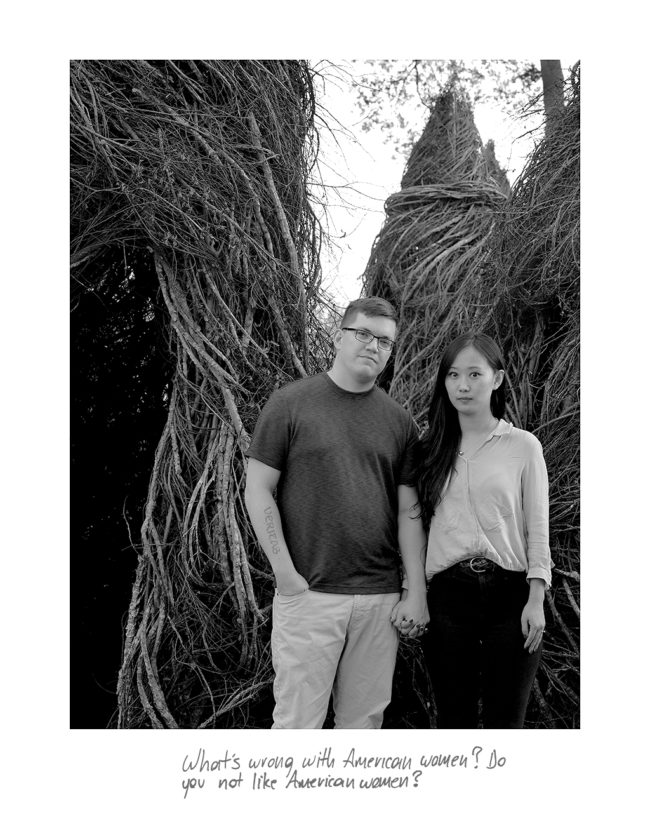

Donna Pinckley, based in Arkansas, had work that I was sure I had seen somewhere, but I couldn’t say where for sure. The project had gone viral, she said, so it could have been any number of places.

Donna has strong, large format black and white images made of inter-racial couples, and includes text written on the bottom of each print. (Racist, nasty comments that people have made before.) It’s really strong work.

It reminded me of Jim Goldberg’s “Rich and Poor,” but Donna and I agreed that just because someone else had written on pictures, (as Duane Michals did also,) then it’s no reason not to do it, if the situation is right.

Mayumi Lake works at the Art Institute of Chicago, where she went to school, and showed me a couple of projects that weren’t quite right, for me. But art is subjective, and she clearly knows what she’s doing.

As is often the case, we might resonate with something else, in a different box, and that’s what happened here. Mayumi is Japanese, and these flowers she makes out of scanned bits of vintage kimonos are so cool.

Sleek and colorful, vibrant and personal. I liked them very much, and think you will too.

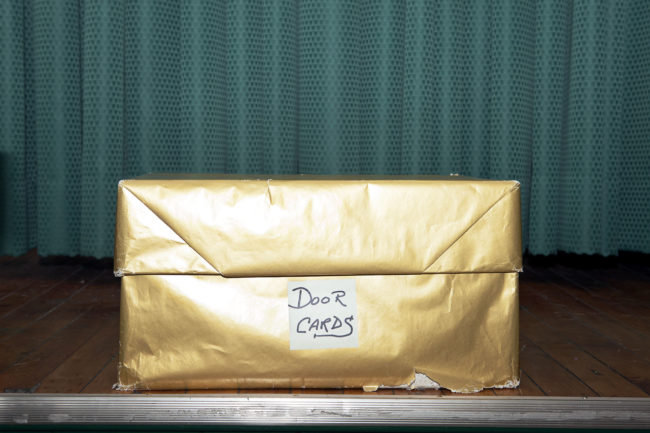

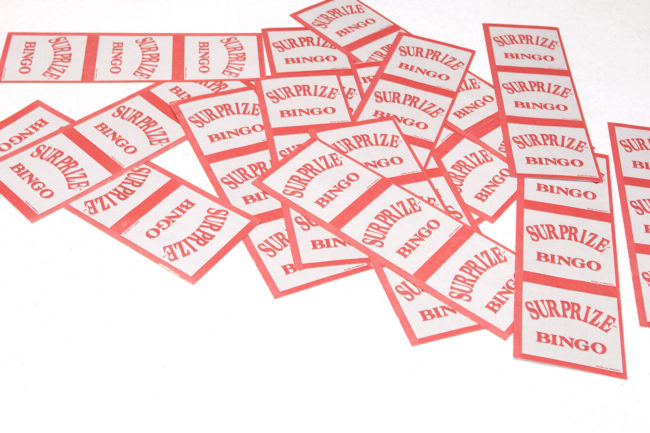

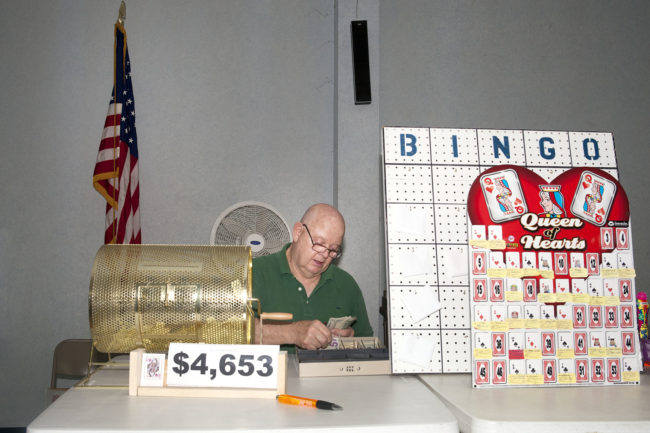

Kalin Haydon, a graduate student at Columbia College, showed me a project about bingo hall culture in Southern Illinois, as she grew up around such places. (We discussed the bingo hall sub-plot in “Better Call Saul,” and both agreed it’s stellar.)

I thought her strongest images were really tight, as they walked the line between being respectful, and showing a vision that might in some ways be perceived as pejorative.

It’s the hard part of doing a story from the inside, knowing you want people to appreciate what you do, and share your respect for the subject, while also being aware of the visual elements people are sure to find compelling or salacious.

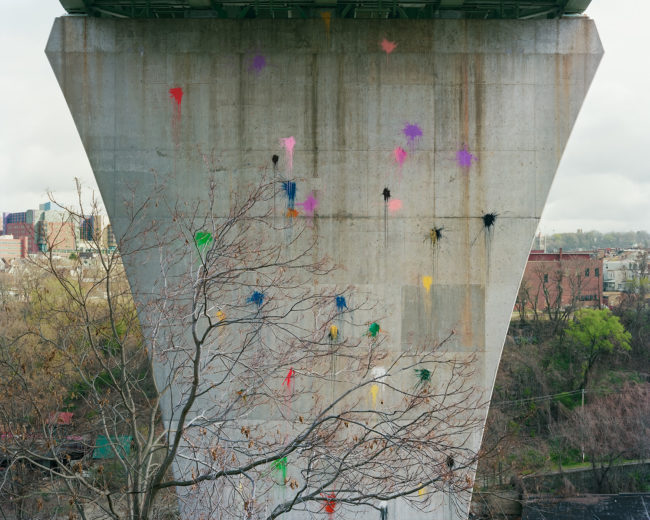

Adam Davies was in from Baltimore, where he is an Artist in Residence at Creative Alliance. He presented a project of large format, urban, structural, architectural photographs that featured subtle use of graffiti. (Found, not made.)

There were certain perspectives that felt dangerous, like, “how the hell did he get up there?,” and overall I found them to be striking. I mentioned the few that I thought looked too much like other people’s images, but in general, think the work is excellent.

I met Susan Keiser, and showed her work here, after Filter in 2015. (She’s the first Filter alum to make it back into the post-festival round up.)

Her exploration of dolls fascinates me, as that would be a subject on my “cliché/don’t do this” list of things I’d give to students, if I had such a list. (I don’t.)

But I always challenge students to see if they can bring a fresh take to well-trod terrain, because who doesn’t like a good challenge?

This time out, Susan is shooting through ice, using vintage dolls from the 40’s and 50’s that she collects on Ebay. Even better, they’re small, so she has to use a macro lens to capture the scenes that she renders with the dolls.

Susan is also a painter, so the use of color and composition is right, leading to an overall creepy-but-not-too creepy vibe I really like. Crazy pictures.

Finally we have Allen Wheatcroft. Here, we return to that question of when are pictures appropriate or when are they exploitative? Or is it OK to be exploitative anyway?

Allen had street photographs from around the world that often (but not always) featured a lone figure in a crowd. Someone Allen described as off, or not-quite-right, but not hardcore junkies or homeless folks.

We discussed whether these people weren’t proxies for him? Whether he didn’t see himself as awkward or uncomfortable, unable to easily connect? Allen agreed that he did, and it was a really interesting way for me to understand the pictures.

He asked me if I thought they were too Bruce Gilden, or inappropriate towards the people in the images?

I don’t think so myself. I find them a bit intimate, and strange, and more endearing than critical. A bus driver in Stockholm? A guy on the beach in Chicago? More odd than off-putting.

We’ll end here today, with a group of pictures that represents some of the best the street has to offer…

Synchronicity.