Alex Rudinski, Wonderful Machine

Shoot Concept: Fashion portraits of two models in an urban setting

Licensing: Native Advertising use of six images in perpetuity

Location: Exterior locations throughout Manhattan

Shoot Days: 2

Photographer: Fashion and beauty photographer based in New York

Agency: Regional lifestyle magazine

Client: National hair care brand

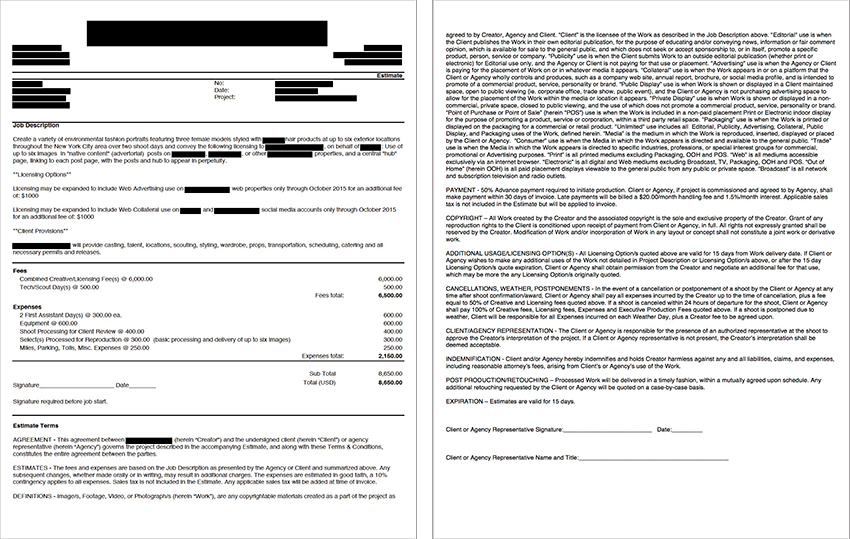

Budget: $8000.00

Licensing: As many struggle to find new streams of revenue and monetize consumers accustomed to getting their content for free, we’ve been receiving more and more requests from photographers working on advertorial or native advertising projects. Many media companies have taken on the challenge, with varying degrees of success. Much derided and often ignored, advertorials and native content are hard to pull off right. Some are overlooked completely, some annoy consumers, but the absolute best provide useful content that promotes the associated brand subtly and contextually, leaving a positive brand impression.

We were approached by a fashion and beauty photographer to help draft an estimate after she was contacted by a major lifestyle magazine based in the New York City area. The magazine was working with a national hair care brand, and was looking to produce some photos of professional talent styled with their client’s products for use on the magazine’s website as a web-only advertorial. The photos would show the fully-styled models in urban street scenes alongside videos explaining how to achieve the styles the models were showcasing with the brand’s products. Apart from being hosted on the magazine’s primary website, the photos and videos (shot by a separate crew) would also be featured on a fashion-centric blog owned by the magazine as well as a microsite that would host all the content indefinitely.

Because of the nature of this use, it might seem it doesn’t fit cleanly within the normal terms we use to describe licensing (which are Advertising, Collateral, Editorial and Publicity). However, we consider the use to be more along the lines of what we might normally call advertising use, due to the value the client is getting from the images, and the final use of those images, being similar. Of course, the client views this as a more editorial use, and wants to pay accordingly. Beyond the client’s ecpectations, due to the limited distribution (the magazine and its websites only) and the one-and-done nature of the project, we can’t charge as much as we might for what we typically call advertising use.

While this modern use of native advertising is still fairly new, the advertorial has been around for a while – think of all the “Special Advertising Sections” you’ve seen in magazines. As such, some of the tools we consult when calculating licensing fees do contain a print advertorial option. Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite hit the mark in this case. Fotoquote, which includes a print advertorial option only, calculated $687 per image per year, while Getty Images quoted $2,230 for the same. Blinkbid’s Bid Consultant (which doesn’t really have enough options to appropriatly price this scenario) came in at $3,600 on the low end, and Corbis arrived at $1,080 for print advertorial use. Searching for web advertising use, Fotoquote gave me $671, Getty (which calls Web Advertising “Digital Advertisement”) returned $1,205, Corbis provided a range of $305 to $763 and Blinkbid offered information of the same accuracy as earlier.

As you can see, these numbers are all over the place, without a clear consensus. You might land on $1,000 for the first image for one year, which would be a sensible place to start. But perhaps the most salient consideration for this job was the client’s specific budget. The photographer was eager to get the job, and inclined to try and work within their parameters. As hard as we might work to divine the “objective” value of the image, if the client isn’t willing to pay that amount, we won’t get very far.

Client Provisions: The magazine had picked out the six locations, hired the talent, arranged transportation and designed the looks. The brand provided their own stylist, well versed in using only the brand’s products to achieve a variety of looks. Lighting was naturalistic, requiring minimal gear, and the on-the-move nature of the shoot prohibited much catering or wardrobe. The photographer, stylists, client and talent would drive around New York in a Sprinter, jumping from location to location. Overall, the magazine would be providing a lot of what photographers are normally asked to provide and what we normally include. This helped us keep our costs down, and also made pre-production a relative breeze. To avoid any miscommunication about what the client would provide and what the photographer would be responsible for, I included a list of client provisions in the estimate’s job description, listing everything that the client would provide clearly and completely.

Many of the provisions would be supplied by a video team that would be following along, capturing some BTS shots and creating how-to videos showing how the models were styled. In different ways, the photographs and the videos would be equally as important to the overall campaign, and just as prominent in the execution of the advertorials.

Tech/Scout Day: Even though the locations would be chosen and vetted by the magazine’s creative team, the photographer would need to visit each location to plan how she might shoot there. With six locations to get through in the day and an unknown amount of travel between, working quickly would be crucial to a successful shoot.

Assistant: Considering the lighting requirements (little) and the additional bodies (several) we opted for only one assistant here. We might have included a second assistant if not for the client-managed video crew, if only to make sure that the area of the shoot is secure. That aspect would be handled by the client and their video team, so in this case our photographer only needed her trusted first assistant. The client was fine with the idea of reviewing images on the back of the camera, so we opted not to include a digital tech.

Equipment: Even though the client was looking for natural light, we wanted to make sure there was enough money available for the photographer to rent additional lenses, or provide subtle lighting to supplement the existing scene. This money would also cover the photographer’s owned equipment, rented to the production at market rates.

Shoot Processing for Client Review: After the shoot, the photographer would need to upload all the images, cull the unusable frames, lightly batch process the images and upload them to a web gallery for the client to review and make their selects from. This takes at least a couple hours, so we want to make sure the photographer (or her retoucher) is compensated for the time, skill and equipment required to produce the previews.

Selects Processed for Reproduction: Once selects are chosen, the photographer will need to process the images for use in the final product. Some photographers might call this retouching, but in order to avoid confusion about how much or what kind of digital work a photographer is doing, we use the word “processing” to describe the work the photographer does to the images without specific client requests, and we use the word “retouching” to describe requests that the client makes after that.

Miles, Parking, Tolls, Misc. Expenses: During the scout day, the photographer and her assistant will need to travel and eat—this fee allows us to get reimbursed for that expense. This also gives us a little wiggle room if a line item turns out to be more expensive than we expected. We include this sort of line item on every shoot as a safety net to catch either small, unforeseen expenses or lump several minor expenses into one category.

Result: We were able to get a budget from the client before-hand, and we knew this was a bit above what they were hoping for. However, we were able to negotiate an increase to cover the additional cost, and the shoot was executed smoothly. The photographer delivered images quickly, and the client loved them. The images complemented the text and video well, helping to create social engagement and drive traffic to the client’s website.

Hindsight: As great as it is when a client accepts an estimate immediately, it always makes me wonder if we underbid the project. I’d much prefer to negotiate to reduce the costs for a shoot to a specific amount than submit an estimate that’s accepted without any negotiation. In this scenario, we were able to do just that – come in slightly over budget and negotiate approval, thereby getting as much money for the photographer as we could. We could have come in at or under the budget, but in the end we would have forfeited money on what was already a slimmer shoot.

If you have any questions, or if you need help estimating or producing a project, please give us a call at (610) 260-0200. We’re available to help with any and all pricing and negotiating needs—from small stock sales to big ad campaigns.

2 Comments

This is such vital information for photographers thank you for sharing it. I would love to have you speak to my students inFebruary when they are taking an editorial class. Are you in NYC?

Very interesting. Great to get an insight in pricing and negotiating for commercial shoots. (there is usually not much information available). I always feel that sometimes the pricing depends on the client and the budget.

This is definitely great information to have it publicly available on the internet. Much appreciated. Thanks a lot. Greetings from Down Under.

Comments are closed for this article!