Jonathan Blaustein: Full disclosure. I’ve known you for years, as a client and a friend. I am on the record in multiple places as being a huge fan of you as a person, and the work that you do.

Mary Virginia Swanson: Yes. Thank you.

JB: You’re welcome. I’m may not be impartial here, but I also have some inside knowledge as to how you operate, and why so many people think highly of you.

MVS: Thank you. I absolutely think that you are a fan of my teaching, and the way I think about the industry.

JB: Right.

MVS: So I’m really happy to have this opportunity to tell you about my latest venture.

JB: Honestly, our readers at APE know me for the 21st Century Hustle, and there are clearly elements of that philosophy that I’ve cribbed from working with you. So in that regard, I apologize if I’ve ever stolen too brazenly.

MVS: No, that’s a compliment. You know when your teachings get carried out into the world that’s a compliment.

JB: Fair enough. I’ll take that as apology accepted. So many people know of your reputation, and that you’ve had a really long career in the industry. You’ve done so many different things- you ran a stock agency, you’ve done consulting, you’ve published books, but the big news is that you recently accepted the position as the Executive Director of the LOOK3 Festival in Charlottesville, Virginia.

MVS: Correct.

JB: And this was in September of 2015. Is that right?

MVS: That is correct. The festival is always in June, and in hiatus for the summer months afterwards. We’ll to be working into the beginning of July, but then we go quiet for a couple of months. It was during that period in 2015 after the close of the ’15 festival that I got a call from Nick Nichols, who is a longtime friend of mine, and one of the founders of LOOK3.

He asked if I would be interested in taking on the leadership of LOOK3. So we embarked on a period of time where I was being interviewed, my husband and I came here to Charlottesville to meet the board, meet staff and just check everything out. I think it was September 8th, we announced that I was accepting the position, and we had a board meeting a week later and began to start to plan this year’s festival. And now we’re just under two months out. We’re ready to roll.

JB: You say it so casually, but was that phone call out of the blue? Did you have any inkling that they were thinking about you? Had you put out little feelers? Walk us through how this happens, because it seems like a big deal.

MVS: Well it is a big deal, and I should say that I’ve been aware of the festival of course throughout its life.

JB: Of course.

MVS: It is a long ways from home. As you know, I often teach at the Santa Fe workshops in the summertime, and some years it just wasn’t on my calendar that I could make it. Other years it fell smack on my birthday and I travel so much that that’s one time that I try to be home with my family.

It was in 2013 that Nick and his team called to ask me, or 2012 I should say, to be part of the 2013 festival. I was thrilled to be able to do that, and I helped them organize some panels, and taught a seminar myself on sustaining your long-term personal projects. That happened to be the seminar that I was giving.

The education was held at the front end, and I remember Nick came by to visit my classroom and say hello, and we had lunch and he said, “Take a good look around at this festival because someday I’d like to have you a lot more involved.”

JB: That was a big ‘ol hint dropped right in your lap.

MVS: Yeah, it was a big hint, and it gave me a chance, to be in the audience for all the talks, and see all the exhibits and the other components. It was wonderful, and we actually did embark on some pretty heavy conversations about my taking over the festival at that time in ’13…

JB: At that time.

MVS: But my family life is in Tucson, and I wasn’t willing to move permanently to Charlottesville. The board wasn’t willing to take that on at that point. They did hire someone who was willing to move, and then they came back to me again when that person had resigned.

At the end of the ’15 festival, we opened the conversation again. At that point, they made it clear from the get-go that if we came to an agreement, that I would not have to move. So we built my contract based on me being able to stay in Tucson; to stay visible in the field which of course is a plus for LOOK3 as well and here we are.

I did agree to be in Charlottesville for just about three months leading up to the festival, and obviously I’ve been here periodically throughout the year meeting local stakeholders, and working closely with my colleague Lisa Draine, long time Festival Director. It’s a fantastic community.

UVA is an extraordinary presence in this town, and it’s a really cultured environment that embraces photography in our world so I couldn’t be happier.

JB: Okay. That makes a lot of sense. I had a hard time imagining somebody like you, who’s so methodical in the way you’ve built your own career, and the way you teach people, that it would have been a random thing.

MVS: And I should say going backwards that when I was first out of graduate school at ASU in Tempe, my first full time job was at the Friends of Photography in Carmel as you know, Jonathan.

JB: Working with Ansel Adams.

MVS: I coordinated education programs there as a young person in the field, and one of the workshops that we did was called “The Photograph as Document,” and there were five faculty members on it: Burk Uzzle, Danny Lyon, Morrie Camhi, Louis Carlos Bernal and a young woman named Mary Ellen Mark.

One of my students in that workshop was a young photographer named Michael K. Nichols. So Nick and I have known each other since 1983. The following year, when Ansel passed away, I moved to New York to work for Magnum, and Nick and Eli Reed were the two Magnum nominees that year.

So we went into next phase of our lives together, and Nick ended up making a big decision, which was wonderful for him, to become staff at National Geographic, and do the extraordinary natural history work that he’s done all of his career.

We stayed in touch as best we could through those years, and our relationship has really been rooted in teaching. When I got to Magnum, I organized the first all-Magnum faculty workshops as well that Nick participated in. To be fair, we really had this strong link to education all the way back to the earliest points in our career.

JB: That’s a perfect little segue. I was so curious personally, and as a proxy for our audience, as to how Swanee becomes the head of a historic and important festival. So after the first question, how did you get the job, I wanted to hit you with something broader.

Why do you love photography so much?

MVS: Photography for me has always been a connector. I think people that are involved in music and performing arts, we all feel that if there’s something in our life that draws us together; that gives us a conversation, and challenges us, and causes us to love things more. It’s a wonderful thing.

I grew up in a family that was the household that everybody hung out at. And my parents were both very involved professionally in gatherings. My father organized conferences in his industry, and in junior high and in high school, I used to go with him conferences that he was running. My mom was very much a community leader. So we all had our thing and for me, it was specifically photography.

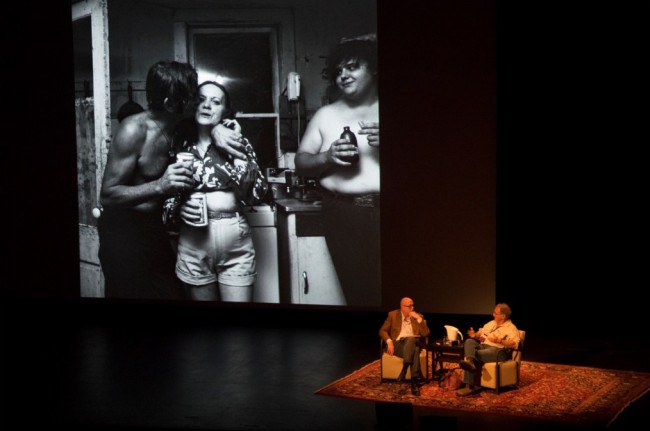

I’ll tell you one thing that really rocked my world as a young person was my hometown curator in Minneapolis was named Ted Hartwell, and he did the first big Richard Avedon show of his private portraiture. It was an extraordinary, wild, crazy installation with images that were of the “Chicago Seven” that were pasted on canvas that was fraying on the edges that was the size of the walls.

He and Marvin Israel, the designer, and Diane Arbus came in to install the show and they painted the floors and the ceilings and everything was wild and it was completely different than growing up with Life Magazine and National Geographic and all and it just made me realize that it could be a completely different kind of communication tool.

JB: Sounds wild.

MVS: I’d seen a lot of how photographs had landed in the artists of the ‘60’s Rauschenberg, etc, because the Walker Arts Center is also in Minneapolis. It’s a contemporary museum, but there was something about that Avedon show, and seeing how different it was presented in the printed age, that made me feel like there was a lot more that we could communicate to each other with.

I never forgot that as I was doing my studies, and learning more about the history of photography. Understanding how important that whole notion of personal work was to Avedon, at the time. As soon as I got into college, I was organizing student art shows, and worked at our museum. I also became the student director of our photography gallery, and it just became this great point of contact for me. For my family, it was other things that drew people together. For me it was photography.

Jonathan: And you got a degree as a practitioner, I believe?

Mary Virginia: Yeah, I have an MFA. I had done my undergraduate, in fact, at ASU in ceramics. I was always interested in art history, and in museum and gallery work, having worked as an undergrad at our university art museum. Those were my three areas.

As I took more and more photography and history of photography classes from Bill Jay, everything came together for me with photography. The museum and gallery aspect of it, the art history aspect of it, and the making work– all three came together, and it was like this explosion.

I often find myself saying this to students, that when you find the thing that you love the most, it will seem like there’s a thousand times more energy that comes out of you that you never knew you had.

Just everything connected for me around photography, and it was at that time that I started my involvement in Society for Photographic Education as a volunteer. We organized a regional conference during my graduate studies there, and I really came to know that we were a community.

JB: OK.

MVS: I’ll tell you another kind of funny thing that happened. At the end of my undergraduate studies, there was an NPPA conference that was coming to Phoenix. It takes different form right now, but in those days, it was called the Flying Short Course. It would a five or six city thing, with five or six different people on this tour.

There was always an artist, and sometimes a curator and a photo editor. I went down to this conference-style hotel for the NPPA Flying Short Course, and the person that stood out to me the most was Mary Ellen Mark. She was just back from her Fulbright in Turkey, and had just started Ward 81. I thought, “My god! This is a much broader world of photography than I’d ever imagined! And she was so courageous. I just was so impressed with her work, and her bravery. Everything about what she was engaging in, and that too really combined for me to feel like this is a community that I want to be a part of…

JB: I had to break in for a second, because I did want to ask you a pointed question. From shortly after you got your degree, you joined the business side of the career, and you’ve been involved in so many different areas of photography that way. But do you still make work? Was there a point in which you made time for your own practice, or did your sort of immersion in the photo-community-at-large satisfy your creative yearnings?

MVS: I made pictures on the way home from work today. I make pictures constantly. What I’m not doing as much of as I would like to is printing work, and that’s sort of just the nature of the beast now, isn’t it, that we’re able to make pictures constantly and still be satisfied by them.

When I was working for the Friends of Photography in Carmel, I started shooting color neg for the first time. I still yearn for the darkroom, of course, but I make pictures constantly. Thousands of pictures all the time. I love my Instagram feed. That’s where people see things most.

JB: Right, well that’s where I know you shoot, but I think you understood the spirit of the question. You haven’t pursued it as art, or there were phases where you have or —

MVS: When I finished up my undergraduate degree, I was completely torn, because I was already applying to graduate schools in ceramics, but by then the photography bug and the art history bug and the museum studies all had wrapped around photography. And so Bill Jay helped me out, and he got me an internship.

I had a really good friend that had moved to London, and Bill got me an internship at the Royal Photographic Society, and also I worked four days a week for something called the Half Moon Photography Workshop. At the time, it was the largest grant the arts council had ever given to photography. I made work for that year before I applied to graduate school, because obviously I had to have a portfolio for graduate school.

JB: Of course.

MVS: And then when I got into graduate school I started spending summers and Christmases interning for Ted Harwell back in my home town museum (Minneapolis Institute of Art). What I came to learn in that period of time, and also running the student gallery on campus, was that I love working with photographs, and I loved working with photographers.

I did do my thesis show, I got all through that, I’m really proud of the work that I did, but when I finished up my degree, I really did not have the bug to be a commercial photographer, a fine art photographer or a full-time teacher.

I wanted to work with photographs and with photographers. I looked for a place that I could work that would give me exposure to lots of different types of things in the field, because we didn’t really have jobs that would be defined like that. I think there’s a lot more opportunities to do that now with online magazines, with all different kinds of collections collecting photography that hadn’t before, and agencies, it’s just a different world.

But at that time, I applied for the job at the Friends of Photography in Carmel because they had workshops, they gave grants, we had an exhibition space and we published photobooks. So those four initiatives were things I knew I could learn from, and I wanted to just sink myself into an experience that touched on all those things.

It’s where I really came to love all those things, which are still part of my practice and my teachings. With publishing, and being on top of helping all of the artists understand how to sustain their long term projects, whether it’s grant writing, or corporate funding. All those things that project from the “Friends of Photography” are still part of what I’m engaged in today.

JB: Your message may have been honed in the 80’s, but it resonates quite a bit in the 21st Century.

MVS: The things I talk about in my lectures with students today are what I learned from different mentors along the way. I certainly learned about community working with Ansel at the Friends of Photography. There’s no question about it. But when Ansel passed away, and I went to work for Magnum, that was a step into a completely different business role.

Yes, I knew about the gallery world, I had worked for Janet Borden at the Robert Freidus Gallery.

But I had no idea what I was walking into at Magnum. I was there to do book projects and exhibitions, so I was still working in my area, but overhearing a new language of business was a mind blower to me. When I stepped into Magnum, I realized that there was a completely different world that we hadn’t had any idea about. You can get all the way through an MFA program, and never hear the word licensing, or certainly not hear stock photography.

But when I got there, I realized that the world was much bigger than I had imagined, in terms of photography, and the power of communication with excellent photographs.

From that point forward, I became an agent, and stepped into wearing many, many more hats, which you know from knowing my teaching, is really all rolled up into one. It’s all part of being a responsible professional in the industry, and my strong encouragement for photographers to understand as many possible outlets for their work, and that each one has a different vocabulary.

Each one has a different deliverable, each one has a different contract, and that to me was like a crash course when I stepped into that role at Magnum, and realized that of course their business model involved all of those.

Jonathan: You were still in maybe your late 20’s, it sounds like?

Mary Virginia: Yeah late 20’s, early 30’s my years in New York. Very, very interesting time in the industry. I’ll never forget this. The very first day that I was at Magnum, I was there to create books and exhibitions from their archive.

Mind you I’d worked in museums, I’d worked in galleries. To me an archive looked a certain way, had a certain filing system. I walked into Magnum, and it was a sea of four-drawer filing cabinets stacked high. You open the file drawer, and everyone’s work was smashed together in these brown manila folders, under headings like “Sibling Rivalry” or “Paris Skyline” or “South of France”, or an emotion like “Cooperation.”

I could not believe my eyes. It was a totally different way of thinking of filing images, or certainly there’s a different language of finding them. I remember Bruce Davidson saying to me that very first day, “Swanee, this is how we’ve been making a living all these years.”

And if you looked hard in the files you’d see that under “Sibling Rivalry” there would be some of his “East 100 Street” work or some of Susan Mieselas’ work with the children in the Americas, or in the dogs category of course it would be Elliot Erwitt. Everything made sense, but what I realized was they were inverting, or taking apart personal projects, and filing them in all these different categories. Cross referencing like mad.

Jonathan: It was like analog tagging.

Mary Virginia: All analog tagging at the time. It made me realize for artists, the best thing that could happen would be to have an exhibition. Even better if it traveled, and even better if it had a catalog, but ultimately in our fine art world, when a body of work was done and the tour was on, we kind of thought of that as old work.

People moved on to the next body of work, and it didn’t have a second life, like the licensing world was affording. For me, it was a super-interesting time in the power of photography.

We were finding that there was a generation of people coming into the decision-making chairs, be they photo editors, or graphic designers or art directors, who’d grown up with cameras and had a different perspective. The metaphor could be king.

Things didn’t have to be quite so literal as they had been in the past, but there wasn’t really an agency bringing that quality of work together.

So at that point I called all my friends that owned galleries and said, “Listen, you’re missing this market for your artists. There’s a whole other world of people who can use the images, and it can help support their personal work. People like gallery owner Terry Etherton were saying, “Oh Swan you should do that. We don’t know anything about that, you should do that.”

I just kept paying attention to all that, and more and more often friends were calling and saying, “Hey I don’t know how to read this contract that I just got from somebody. Can you read this for me? Can you call them?” So I’d call people up and say, “Oh by the way, how did you find Sally Gall?” And they’d say, “We subscribe to Aperture. We subscribe to this.”

Or, “We saw their exhibition.” It made me realize that decision-making group is really in a situation now where they can use great work, and that it can help photographers by functioning, not as a primary market, but rather as a second market. That helped me to become confident in starting something called Swanstock, with Gordon Stettinius (of Candela Books & Gallery in Richmond) as my right hand person all those years, we were learning about all these other opportunities that of course continue on in all of our practice today.

JB: So let’s jump forward for a second then. Listening to you talk, even despite my glowing intro, people can hear the depth of your experience. But at this point in your career, you travel all the time, you’re super established, you teach, you have private clients. Just because LOOK3 offered you the job and said you didn’t have to move, you didn’t have to take it. Why did you decide that this was something you wanted to do at this point in your life?

Why did you say yes?

MVS: I have to tell you, I was so moved by the Festival in ’13. The education was rock solid, the lineup of photographers was so interesting, and so much of it was a surprise. I felt like if I could have a hand in making this festival happen every year, I could in fact impact more people than I could on my own.

I looked at that potential for growing education, and it was really was something that the board and I came together on. They were very interested in me from that perspective, I could bring relevant education to the table. I think that’s where the match was really made and happened was the education component.

JB: So how does an education program at a festival differ from a school or a workshop business? How do you guys differentiate it, or what do you try to offer your community that they might not be getting elsewhere?

MVS: Well first of all, I know from teaching at exceptional places like Santa Fe Workshops and Anderson Ranch and Aperture that there are many places that do their kind of education really, really well. I would never want LOOK3 to be those places. There are lots of organizations to go and spend a week with a photographer.

There are not a lot of places to go and have education and inspiration for photographers at levels of accomplishment, and at all ages.

I feel like our industry is changing so fast, and I get just as many questions from photographers that have been successful in one thing all their life that now are wanting to expand.

Maybe they’ve never talked to a gallery before, or a fine art photographer that’s never had an opportunity to talk to an advertising art director before, or someone hasn’t had any licensing experience but in fact they have unique work that could make a difference in communication.

So that’s the perspective that I brought to it. I feel like it’s just as important a time, frankly, for teachers – an essential time for teachers to be completely current on where this industry is going, as best as we can predict it at this time. That’s been my mission behind putting together education for this year, and my hope is that our education stays incredibly relevant. That it changes out every year to be what people need. And that’s what excites me the most. That’s what I’ve built for this year for LOOK3 in terms of education. We’ve also added a lot of community engagement.

JB: What are some of the programs this year?

MVS: The first thing that we’ve got, I’m hoping that people will travel in on the Tuesday which is the 14th –

JB: Of June.

MVS: Because that night, Tuesday night, we’re hosting the PDN 30 Emerging Photographers panel. I reached out to PDN about this, because I feel like it’s the perfect way to begin to think about the education that’s happening in the next two days after that. To start to focus on what is that path?

How does a photographer set out in the world today? What are the marketing paths that have worked and haven’t worked for them? Where do they find their inspiration?

I don’t know if you’ve had the opportunity to hear Holly Hughes moderate that panel, but it’s not to be missed. I love it. Everywhere I’ve ever seen it, it’s been completely engaging. Then, the next morning, we have two seminar days back-to-back on Wednesday and Thursday.

I’ve designed it to be such that the Wednesday is all about your work, and the Thursday is all about your audience. On Wednesday, I wanted to have a day that would be an overview of all the different tools that we use, in terms of technology to be creative. Not just how we make work, but how we publish work, how we deliver work, how we share work, how technology impacts everything. I call that day creativity meets technology.

I asked Jim Estrin from the Lens Blog to moderate that day, he and Andrew Mendelson from CUNY have helped me shape the day and will both participate. We thought a lot about what people need to know now.

We’ll start with the beginning, Andrew is going to do a kind of crash course on 1839 to the present with technology. Some of the pieces people may already know and be using, like Instagram, and the power of that tool. Other people may not know some of the other things we want to bring to the table, like understanding how we measure success in terms of sharing, the metrics of that.

We’re closing that day, for example, with Jenna Pirog who is the producer and editor of the Virtual-Reality Projects for the New York Times Magazine, so we’ll sort of end with the future.

JB: Sounds exciting.

MVS: And then Brian Storm, and we have Julie Winokur and Ed Kashi taking one of their Talking Eyes Media products apart to show us that path to finding your intention with your project. Who’s the audience for that, where do you seek funding, where do you push it out.

We’ve got the photographers from the Black Box Cooperative coming to talk about a new kind of engagement as a team, quite different than the traditional agency world, but a great example of the younger cooperatives that we see today. Lots of different things like that.

Peter DiCampo and Austin Merrill from the “Everyday Africa” projects are coming to talk about the power of communication through using Instagram. Dan Milnor is going to talk about atypical publishing.

So I see that day as the kind of day where there’s something for everyone in it. It’s of great value for people who have not been in an education environment for a few years, because many of these things they may not have been experiencing before.

I love the fact that we have some young people teaching, that have been out experiencing it in the world, and I think it’s an awesome day for educators to come and have this crash course on that.

JB: What else can you tell us about?

MVS: The second day is called “Artists Meet Your Markets.” That morning is going to be a really interesting, where I have 10, probably 11 different individuals talking almost on script about what their market is, what their product is, who they’re talking to, how they deliver it, how you the artist can make a strong first impression to them.

If they choose to reach out to you to license your images for illustration, in whatever case they work in, they’ll share with you what the deliverables would be and what the contract would be.

I have people like Catherine Edelman coming and saying, I’m a Gallerist: Our audience is high-end collectors of limited edition art work. We deliver to our audience, from our store-front gallery in Chicago, and attending international art fairs. If you want to make a strong first impression, study our website, come and see what we put on the walls, read the captions, the labels, edition numbers, etc.

If we do business together, we represent you. This is what the contract will look like. The deliverables for us is that we need you to invest in an inventory for us.

The next person might be Molly Roberts from Smithsonian Magazine. She is a director of photography at a magazine. Their product delivers informational articles that are richly illustrated in American History, art, culture and science. They deliver it through their print magazine and their online presence. This is how she would say you could make a strong first impression.

This is what she would say about what the contract terms would be and the deliverables. The next person might be an art buyer at an ad agency or someone at a licensing company or someone at a media company like CNN that wants to commission new work.

My goal is that through that morning, one professional after another explains how they engage with photography and hire photographers, what their terms are, how you deliver so that the artists in the audience realize there are other opportunities for you, but each one has its own vocabulary.

Each one has its own deliverables and each market has its own contracts. If you can manage to understand all that, and speak in these different languages and understand these different terms, you have that many more opportunities to make a living with your camera.

JB: For years, you’ve been talking to photographers, and trying to educate them and open their eyes about the ways their images can cross over into other markets, and how they can introduce themselves to new audiences. To me, that sounds like you’re bringing your pure core precepts into the LOOK3 umbrella.

MVS: I agree, and I have to say it came really out of my stepping out of the fine art market only, and stepping into Magnum and realizing “Oh my god, there’s all these other markets that can help photographers support their project.”

JB: And that was Ansel Adams’ philosophy as well. I did an extensive research project about Ansel, and I got to know his business manager Bill Turnage a little bit. If people want to understand your philosophy, and they want to get a detailed message delivered by professionals across the board, they can come hear this kind of thing at LOOK3.

MVS: Exactly. But I want to tell you what happens the rest of that afternoon.

So imagine that we’ve had this morning that’s opened everybody’s eyes and minds to all these other opportunities. That afternoon we have an opportunity for people that have registered for the morning, and been through that training, essentially, to show their work to not just those ten or 11 professionals but I’ve expanded it.

I’ve added more gallerists, more publishers, more magazine editors, more advertising people, more corporate art consultants. We’re filling out this room with what would look to you and to everyone else like a typical portfolio review. But here’s the catch.

JB: BUT! There’s always a but.

MVS: But you the photographer, in this case at LOOK3, do not pick the reviewer. We call this afternoon LOOK3PITCH.

The reviewers, industry professionals, choose who they want to have a meeting with, not a critique, not a portfolio review. I want LOOK3 to be the place where all of you come and have the chance to meet people, and gain confidence in your work and confidence in that language to other markets.

Come to LOOK3 and have a chance to have proper meetings. I want you prepared. If Catherine Edelman says that she wants to see you, you better be prepared, because she considers it a meeting.

Not a critique or portfolio review but a meeting. So it’s a twist on that, and the reviewers that I’ve engaged to come are thrilled with this kind of switching out to where they get to choose. Normally what happens is what just happened at FotoFest. I’d sit down and every morning there would be my schedule.

JB: Right. I think our readers are pretty familiar with the portfolio review format, so it’s interesting to hear you flip the script. I want to pivot again briefly.

MVS: Yes.

JB: The philosophy that you espouse, that you teach, and that you encourage, it’s been around a while. We can date it back to Ansel, and your own experiences. In my opinion, you’ve had a track record of being ahead of the curve, as far as understanding industry trends.

So I would be remiss if I didn’t put you on the hot seat. You’ve been telling people they had to spread out, they had to diversify their income streams, they had to try new things.

You’ve been talking about this for years, and now everybody knows it’s true. I know you’re thinking ahead.

What’s next? Where is everything headed? We’ve seen most of the places that are going to go out of business maybe go out of business. Now, I’m starting to hear that the gallery industry, maybe, is heading towards a huge shake up? How do you see these things playing out on a five year time horizon? What do you imagine is coming down the pike?

MVS: I have to tell you, I think we are at a huge change right now. More so than we’ve seen in our professional lifetimes, with the growth of online-only, and the fact that the online presence in many cases are more important than the print presence.

It’s certainly reaching a lot more people, and now there are all these places that never intend to have print. My concerns of course are rights and fees paid, and the fact that we need all the photographers to make a living. We have a whole generation coming in now that will be photo editors that maybe never worked in print, and everyone’s on such a high learning curve it’s wild.

I’d like to think that in terms of the fine art print world, that we’re growing the diversification of our collecting audience to be much, much more broad. We see it in corporate art, we see it in some of the huge empires in the hospital world commissioning work and really engaging in that way.

The magazines we see getting smaller, the online presence getting larger. I’m very concerned about the pressure on photographers about what they can release when, because then if they say yes to one magazine then they may never get the one they really want because they’ll say it’s already out.

We are in a time of real upheaval, and I want all of those next-generation of photo editors to be at the tables with those that are sage. Those that have been in the business for years, and hopefully not only influence their capabilities, but influence their understanding of the needs for photographers to keep their rights, to be paid fairly, all of those things.

So I’m cautiously optimistic in terms of the online world. I’m more optimistic than ever in terms of the print world, the collecting world, but we’ve got to all juggle things. Everyone has to understand all of the language, so that they can dabble in all of it and see what’s going to click for them body of work by body of work. That’s not been the way we’ve been thinking before.

JB: It seems like a lot of money flooded out of the system in general. Certainly as content became free, and companies weren’t able to stay in business just selling online advertising, so there’s been an outflow of capital in some ways, but a massive in-flow of interest.

When I do these interviews, inevitably we discuss this overwhelming demand for photography. With the smart phone revolution, with Instagram, we’re looking at billions of people who now have a passion, where the overall community used to be a fraction of that.

I feel like a lot of people see this extreme interest in photography as an eventual lead-in to maybe a new phase where capital comes back in to the industry. Where people make money in different ways.

Do you feel like the growth of global interest will ultimately be commodified, or do you think it might stay discreet from the capital flow?

MVS: Tell you what gives me optimism about the capital coming back in. More and more photographers I talk to are actually challenging the rights. They’ll write someone and say ‘no, I’m not going to take this for the cover; this is the price you offered for the inside,’ or on page 1… the home page is going to cost more.

Photographers are starting to understand how to leverage the value of their brand, and actually speaking up about it. You know me well enough to know I’ve been preaching that, I preach registration and copyright, keeping a paper trail, all of those obvious things, but I’m empowered lately by the fact that I’m hearing more and more younger people rise to that.

I’ll share with you that at Photoville this year, when I had just taken the job about a week before, I ran into Jake Naughton and his colleagues at the Black Box Cooperative. And I said to them, I said, “Let me turn the tables to you. How can we help you at LOOK3? What do you need at LOOK3 edu this year?”

Jake looked at his colleagues and he said, “Well.” And he looked back at me and he said, “None of us has a job, and we’re starting to realize that we probably never will. That the entire role of a staff photographer is out of existence. There are no jobs in the industry shooting that’s a full time job.”

He said, “We were not trained to be entrepreneurs in college, and we’ve got to learn to be.” That’s really where pitch came from.

That next morning, I was at Ed O’Keefe’s office at CNN and I shared with them this experience. It really helped me to shape what I wanted to do with edu, and he said, “You know, I bet they don’t realize that they could come in here and pitch me on a story.”

I said to Ed, “Not only do I think they don’t know that, but I don’t know that they’ve ever had that chance. I don’t think they have the experience to do that.”

I remember back when Darius and I did a seminar on portfolio reviews at PhotoPlus Expo, and we did a role play…

JB: Darius Himes.

MVS: Yeah, my co-author Darius Himes. We did a role-playing thing in front of the audience, and it was a lot of fun. But it made some serious points to people, and that’s really what I want to happen on that pitch day. I want people to have the opportunity to get more confident, and more comfortable with that language, and with that experience. To be ready to handle tough questions from people.

I think it’s just as important for us to be teaching not just the pitch, but the contract terms and the understanding of the rights. You know I’m constantly sending people to ASMP.org and to join their local branches, and to learn from those that have experience managing their own careers. Those who’ve been entrepreneurial for all of these years.

It’s part of why I want teachers to come. We’ve got to help this generation, and the next generation of photographers, be entrepreneurs, be young business people. The same with photographers that have had their whole life in one aspect of the career, where now they want to test other waters. They’ve got to learn from scratch too. When it comes back to the individual photographer, and they can manage those relationships well, then everybody is going to win.

JB: Here’s another big question then. LOOK3, which at least according to lore began as a projection in —

MVS: Nick’s backyard.

JB: Right, Nick Nichols back yard.

You’re a big, bold, ambitious person. But it’s still a festival model, and is built on this idea that there’s a get-together, a big community event that everybody flows in for and then, things ramp down, scale down on staff, save money, then ramp up again.

I’ve been to many festivals, and our readers have heard my experiences at Filter, Medium, PhotoNOLA, FotoFest and Review Santa Fe.

There are organizations around the country and around the world, but certainly we’re blessed here in the United States. Can you imagine something like LOOK3 expanding to the point where it’s not about the one big weekend? Can organizations like yours grow in ways that move beyond the tent-pole event? Or do you think the festival model stays rooted in a week a year?

MVS: LOOK3 has a community that gathers every year. It’s just like some of us that have been around certain things like PhotoNOLA since the beginning. We look forward to seeing our friends, our colleagues, the local gallerists, the local museum curators, the local NPPA photographers.

Everybody is one big community when we hit town, and there’s no question it feels that way at LOOK3. Even Jake Naughton from Black Box shared that he’d come every year since college. People come back to that place where it began, and certainly the city of Charlottesville is so proud to host it that I can’t imagine us not having something here. But I will tell you…

JB: I didn’t mean not having it each year. I meant, having more than one? Or having year-round programming so that the festival only becomes a part of the organization’s identity?

MVS: Right. Well, remember my roots in the Flying Short Course. I can’t tell you how important it is, I think, to roll things out to other communities. Whether we can pull together an economic model that will work to do that? But it’s certainly something that I talked about while speaking with my board about taking this job.

LOOK3 does a really excellent job regionally, where people can drive to it, but I don’t believe that we’re reaching everybody even in the US, and I would love to have us do some sort of remote work. I’m also really interested in where we’re going with the capabilities of live streaming, and I would love to have us connect with other festivals and do some live sharing of things that are going on around the world at festival time.

Next year is our tenth LOOK3. I really want to change it up and do some different things. Obviously I’ve got two months of programming to get out ahead, but believe me, we’re thinking long and hard about what kind of statement we can make.

You know, it’s wonderful watching other festival directors come every year to LOOK3. The head of Visa pour l’Image comes and the head of World Press plans to come. People that are engaged in a very global audience love coming to Charlottesville to LOOK3.

I’ve got to see what we can all put together, but I can tell you that I’ve had festival directors from all over the world reach out, and I would love to figure out a way that we could connect in that way as well as connecting regionally. Anything is possible at this point.

I’m really optimistic that we’re going to have a great year this year, and people will embrace the kind of change that I brought in, and we’ll get feedback from people about what else they’d like.

There was a section on our website leading up to this festival, where I reached out to the public and said what are your education needs now and what work inspires you? It went straight to a Google doc that we could share with our board of what everybody was asking for.

It was incredibly informative for me, particularly the education needs, because it kind of underscored my hunch of what was not being delivered either through colleges or through professional associations to photographers today.

But, I’m all for the biggest community that we can have, and sharing as economically so we can all continue to be physically present, but be able to reach people abroad. Have you had that experience Jonathan, that you’ve seen some live streaming from festivals that’s been engaging for you?

JB: Well, since you’re putting me on the spot, I will answer honestly, which is no. Not yet. But I do have painfully slow Internet out here in my horse pasture, so perhaps that might have something to do with it.

Listen, we’ve talked so much about LOOK3, and we’re getting to that point in the interviews where they start to wind down a little bit, so sometimes I like to be proactive. One of the things that I think that has amazed me about you is that you’re based in Tucson, with massive saguaro cactus’ in your yard, but you travel constantly.

I thought we’d kind of pivot a second and just have a little fun, and then I’ll let you get back to your evening. I know you’re not the type of person who would ever pick favorites, or what you like best, so I’m not going to ask the question that way.

But, if you knew that tonight was your last night on Earth, and you could have one slice of pizza, or one plate of food from that one little joint that you love in Chicago or L.A. What’s your go-to if you only got to have one plate of food from anywhere you’ve been, what would it be?

MVS: Oh my god.

JB: I’m totally putting you on the spot.

MVS: Oh you are. I’m really stumped.

JB: I know, I know. Maybe a couple of your favorites? What do you love?

MVS: I love being in New Mexico. I love being in New Orleans and of course I love being in New York. I never get enough time in San Francisco, it’s so damn expensive even just to fly there let alone get a hotel room anymore. It’s hard to engage, and we all want to be at Pier 24 as often as we can, right.

JB: The place is pretty great, though I haven’t been back in a while. But come on. You can say a big slice of New York pizza off the street, but I don’t know if that’s true. Is it a bowl of gumbo in some little back-alley joint in New Orleans?

MVS: Yeah, it’s posole, of course. I love my posole at Tomasita’s in Santa Fe…

JB: All right, there’s one.

MVS: One of the neighborhood joints.

JB: OK.

MVS: I rarely am in Tucson, so I love some of the food in Tucson too. We have a very different style of food from South of the Border. There’s a little Vietnamese place I love in New York. My favorite bagel shop of course is New York. Things like that.

JB: You gave us something. We always talk about photography. I love food, so I wanted to see what you brought to the table. You gave the shout out to New Mexico.

MVS: Yes.

JB: Do you give yourself a set amount of time that you’re going to devote to LOOK3, or do you literally just take it one day at a time?

MVS: Oh yeah, I need to get through a year of this, because I need to learn the system, and I need to understand every venue, and all of our partners and their needs and our sponsors and their needs. Our program this year has a much more diverse range, not just in nationalities and race and types of work, but it’s different generations.

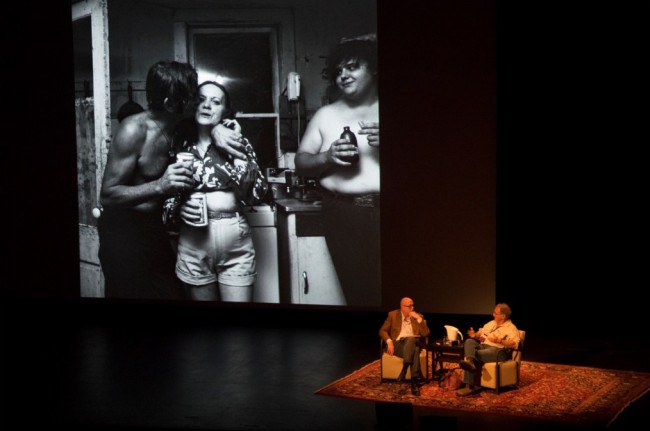

We have the youngest speaker ever on the stage this year, Olivia Bee. It’s a big mash up, and a wonderful, wonderful experience. We’re testing a lot of new venues this year that we haven’t used before. I want to focus hard on this one year and get through this cycle, and then see what needs to be tweaked. That’s more my style, to run it where it has been, make tweaks as I can as it goes along. Tomorrow we’re doing our second round of testing on the big screen at the Paramount Theatre with new projectors. I’m getting involved in all those little aspects that are key.

JB: And you love it.

MVS: I love it. I love it. My personality, the way my brain works, has always been sort of the producer’s mindset, whether I was running a comprehensive workshop program or education program or in a school or putting together book projects, it’s production. It’s something that has a beginning, a middle and an end. Not a lot of routine. That excites me.

I want to make sure that LOOK3 is offering the most relevant education that we can each year, according to what the needs are in the industry, and what the needs of the photographers are. I want to make sure that we bring completely engaging work to the stage.

We want to bring as many exhibitions as possible. We’ve changed up the way the evening projections are, the outside projections by inviting guest curators to put those together, and so there’s a lot of room for growth. But I want to get through the full cycle before we see where we can improve, obviously. And I think we’re bringing a lot of new audiences to LOOK 3 this year, so it will be interesting to hear what a first timer has to say about the experience. All of those things are incredibly exciting to me. I hope you’ll come Jonathan.

JB: You’re kind of talking me into it. I’ll see what I can do. We’ll also say to all the people out there reading it, if you go, drop Swanee an email. You’ll become data. She’ll take your opinion seriously, right?

MVS: Oh, absolutely. Without any question. We totally do.

JB: Any last thoughts, before we go?

MVS: One thing that’s a little bit tricky– all of your readers should know— is that Charlottesville is a small town. Most people connect through D.C. to make their way down. I’m an Amtrak girl, and now I take Amtrak all the time up and down the coast. But it’s not a massive town for a lot of housing options, so don’t wait too long.

Gang your friends, rent a house together, something like that. Call us if you’re stuck, because we always kind of know… a lot of people will tell us that they’ve just booked somewhere, and they’ve got six rooms left there, or they’ve got one left over here, and someone heard about a new bed and breakfast that wasn’t on our list, so we add that up on the list. We want to make sure everybody has a place to stay, so they can make the most of their week in Charlottesville.

JB: Which means Airbnb will be a sponsored partner for 2017.

MVS: You know I have this dream actually.

JB: Of course you do.

MVS: I have this dream that we will get all of the owners of AirBnB houses within like a 10 square block area or something. Can you imagine the portfolio walk we can do if everybody is in their own houses and we go through a neighborhood? Wouldn’t that be awesome? ☺

JB: I knew you were imagining it. [laughs] I really wish you well with the new venture. But it sounds like you guys are doing really interesting things, so hopefully some of our audience will go check it out. And now they know they can drop you a note when they’re done.

MVS: Absolutely! And they can drop me a note beforehand. We are really looking forward to hosting all of you in Charlottesville, Virginia.