Part 3 in a series called Shifting Perspectives by Angie Smith

Angie: Tell me how you first discovered photography.

Oriana: I grew up in South Florida. I was 13. My dad, who as far as I’m concerned was the original geek, had gadgets everywhere. He would take apart the family computer piece by piece and put it back together again. He was always on the cutting edge of technology. He had a Wired magazine subscription that I would flip through as a kid.

I was an indoor kid for a lot of reasons I didn’t understand at the time. Growing up I just thought, ‘I’m shy. I’m scared of people. I don’t like people. I like my books. I like my quiet.’ I could control the stimuli in my room. Later I was diagnosed autistic — I got that diagnosis in 2022.

One day my dad knocked on my door and tossed this brick at me. It wasn’t an actual brick — it was an HP digital camera with 1.2 megapixels. He said, ‘Go outside and make some pictures.’

I said, ‘No, I don’t want to go outside.’

And he said, ‘You have to. Spend an hour taking pictures.’

So I stayed on our block. I avoided eye contact with people, looking down at my feet the whole time. I made pictures of shadows, dew drops on the grass and flowers– just inanimate objects that I could get close to and observe. I ended up staying outside for three hours. After that first shoot I thought, ‘Wow, that was really fun.’

I started carrying that brick everywhere I went. With a camera in my hand, I felt in control of how I was moving through the world. All of a sudden, I felt like talking to people.

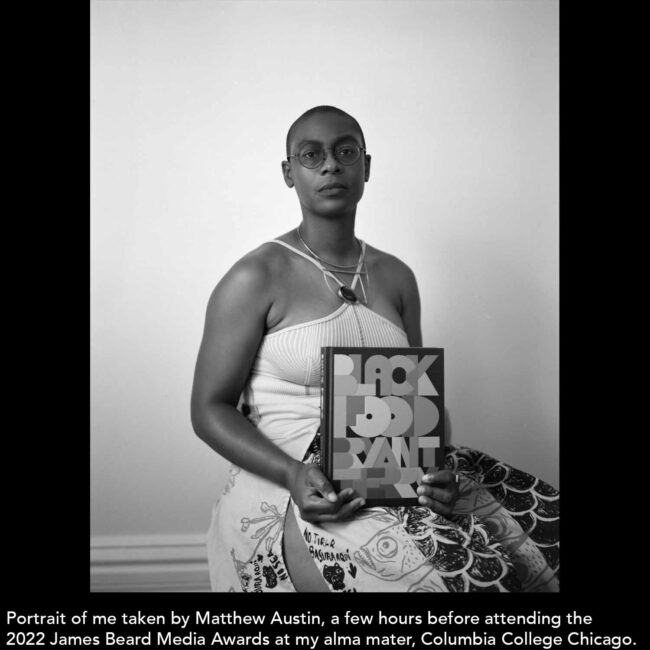

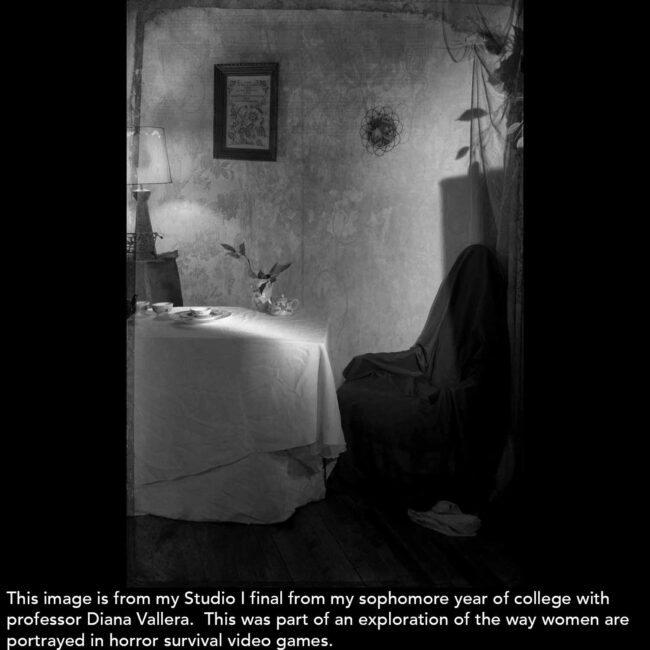

That turned into me taking AP studio art in high school. I started making photographs of my friends. I got really interested in feminism at the time and how women were being portrayed in photography and in art. I ended up submitting a self-portrait to the 2006 Scholastic Art and Writing Award. I won a national silver medal for my self portrait and then matriculated into college and I got my BA in documentary photography.

Once I decided I wanted to be an artist, I thought, ‘I’ve got to get the fuck out of Florida.’

I went to Columbia College Chicago, which is a small private art school. I don’t even remember how I first heard about Columbia. We had spent quite a few holidays in Chicago—my dad still has family here—and it was a 360-degree experience compared to how I grew up in South Florida.

Museums were accessible, libraries were important, the city was vibrant.

Angie: How did you get into shooting weddings?

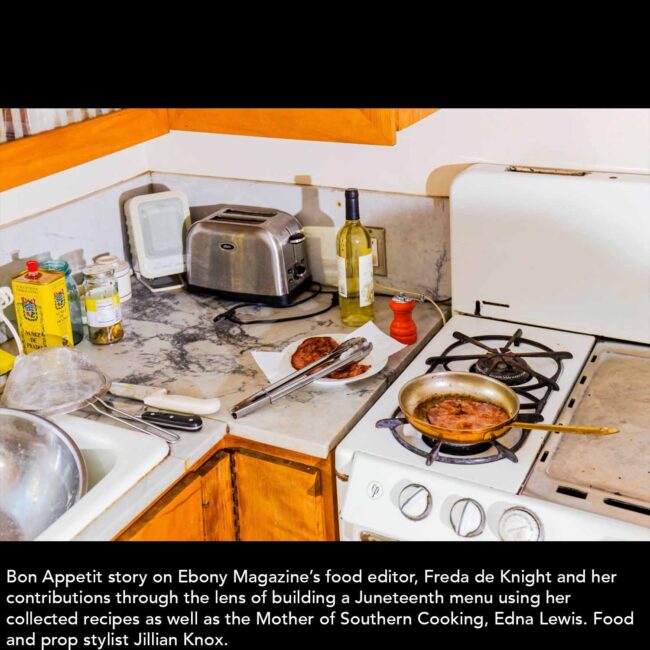

Oriana: I was doing weddings and food photography in Chicago from 2010 to 2014. Growing up, I loved cooking and was constantly checking out cookbooks at the library. At one point, I thought I wanted to be a pastry chef. I loved watching the Food Network.

I started doing wedding photography because I was sold on the idea that you could make good money as a wedding photographer and use that to fund the documentary work you wanted to do. I am a Black, visibly Black person walking around in the world, and most of the people I was photographing—people who were getting married—were white.

There was no amount of qualification I could give clients where I didn’t have to justify why they should pay me what I was charging. It got to the point where, in my second-to-last year of shooting weddings, I literally broke down by the hour why people were paying me $2,000 to photograph their wedding. It was exhausting. So it wasn’t surprising when the same thing happened in the editorial space. I thought, ‘Oh, this again.’

My partner at the time and I moved to Los Angeles in late 2015. I had done one portfolio review earlier that year, in March, with the photo director of Los Angeles Magazine. This person told me, ‘We actually don’t have a lot of good food photographers in Los Angeles, and the city is really starting to become a food city.’

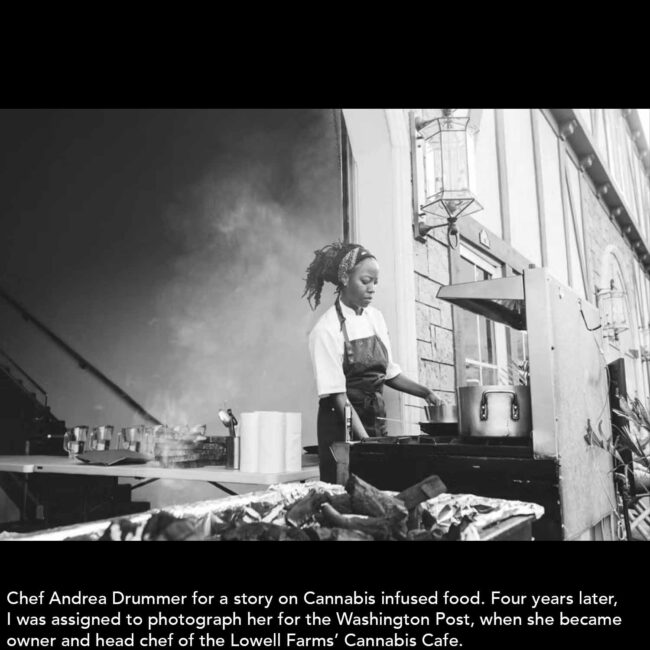

I know that when I signed my contract with The New York Times, they were still paying $200 a day for a day rate. I was one of the few photographers willing to shoot for newspapers. Everyone else was chasing magazine jobs, which I thought was insane. I remember thinking, ‘Oh, newspapers—they go out on a regular basis.’ I understood why people didn’t do it, but because others didn’t, I ended up covering every food story in LA and Baja for The New York Times for two and a half years. That led to The Washington Post and then to digital publications. That’s when the food work really picked up.

I was really lucky to get a digital story into Lucky Peach before it folded. That was a career high, because it was one of the things I had been aiming for. I just wanted to be in an issue of Lucky Peach. But the real thing that saved me—on top of photographing for newspapers—was that I could pitch. I had ideas.

I realized, ‘This is how you get work.’ Unless we do it—as people who are not adequately represented in the industry—no one’s going to do it. When those stories get accepted, and it’s something that came from your soul and your observation of the world, it becomes more like a collaboration with the photo editor. And it’s so sweet when it gets published.

So I became a pitching monster. I was constantly pitching stories.

That’s actually how I got the piece that really broke it open for me in terms of exposure—the California Sunday Magazine feature. I loved that magazine. I loved the photography in it. I told myself, ‘I’m going to be in that magazine one day.’

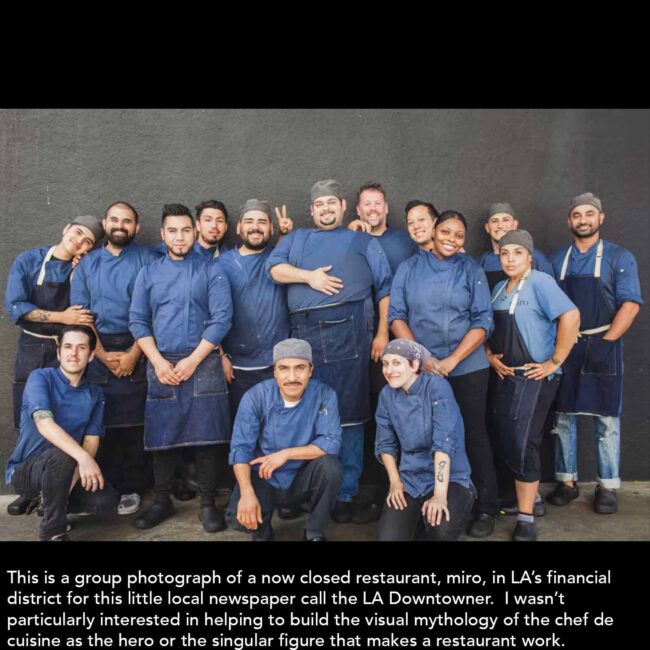

I pitched them a story about chefs in South Central who were harnessing Instagram to sell their food. The story was about the chefs and their ingenuity.I sent them at least a thousand images for my wide edit. When I received their hi-res order, there were no portraits of our subjects, which I thought was extremely odd for a people centered food story. It was about the chefs more than it was about the food—it was about the role they were playing in their community. And that’s how I pitched the story. That’s how the writer pitched the story. So then when I got the high res order, I was like, something is really amiss here.

I sent them some extra pictures and told them ‘It’s kind of not cool for there to not be portraits of the people.’

In my head, I was like, there’s no fucking way this is running without these people’s portraits. This meant something to my subjects. And I wasn’t going to disappoint them because they granted me access into their lives, and that was not something that I took lightly.

It ended up being a 14-page feature. I was fucking stoked. The designer did hand-lettered writing for each chef. Everyone got their moment to shine with their portrait. The moment that story hit the presses, it was nonstop. I got an agent. The feature was submitted to the SPDs for design, and we swept.

Around that time, I had a core group of collaborators—Black women, Black fems, other Black trans people. We were like, ‘Nothing is going to change if we don’t do it ourselves. If we don’t roll up our sleeves and figure out some solutions, it’s going to continue to be really difficult.’

We started doing something that some of the white guys in the industry had long bragged about. When I went to a meeting, I would bring one of my homies’ mailers and say, ‘If I can’t shoot this, the homie can shoot this.’

We just started circulating work amongst ourselves. Then the Authority Collective came into being in 2017 and we launched in 2018. We shared work within a group of 300 people and created a space of accountability when it came to working with publications. That took off in a way I wasn’t anticipating.

Angie: So how did you come to the point where you wanted to walk away from photography even though you were experiencing a lot of success?

Oriana: By March 12, 2020, I lost all of the work I had lined up for that year—email after email after email. In one day it was gone. I thought, ‘Okay, we’re done. There’s no clearer sign that this should be over.’ I came to recognize that I had been working really hard for an industry that didn’t care about my material well-being.

Working during the first Trump administration was a fucking nightmare—working as a Black person who was visibly queer. The things I had to experience on set can only be described as absolutely egregious. And it was every job.

My crews were always majority people of color, almost always women and femme. That was something I was dedicated to. I didn’t like being on set as the only one. It didn’t make any sense to me that it was happening.

The myriad of these experiences made me realize: the problem here is the people. The problem here is a lack of self-awareness, a lack of questioning the system you live under and benefit from.

People should not constantly have to worry about housing, putting food on the table, or having healthcare. The photo industry is not equitable. We’re not getting paid fairly. This industry is deeply racist, sexist, and homophobic. Getting an assignment or not getting an assignment is the difference between keeping a roof over my head or not. This is how I feed myself. This is how I keep myself clothed and housed.

I decided, ‘This is not worth it. My health is not worth it. My sanity is not worth it.’

I’ll be 100 percent real: if you can’t respect me as a human being, you don’t get access to my labor. There’s a reason you have to hire photographers to make pictures—you have to be willing to trust the people you’re hiring.

Whether or not my images are being published does not stop me from being a photographer. I will never stop making pictures. I just don’t want to fuck with y’all anymore.

Angie: So when you moved to Chicago and stopped working in the industry, what did you do?

Oriana: One of the things I started doing in 2016 was collecting books by Black women authors. During Trump’s first presidency, I thought, ‘The censorship is going to come down any moment. This is just the fascist playbook. Let me start collecting these books.’

So when 2020 hit, I read 51 books. That’s when I thought, ‘Okay, I’m going to open a bookshop. Chicago is a great place to do this. This is a city of readers.’

At the same time, I was writing my newsletter and teaching classes. I was thinking about how language works, and what it means to be Black under another wave of repression and dictatorship.

In the back of my mind I knew: ‘I want to do something different. I don’t know what that looks like yet, but I know I’m interested in ceramics. I’m interested in sound and sculpture. I’ll give myself the time and space to figure out this new practice. I’m not going to put expectations on it. I’ll try whatever I feel called to.’

My rent was really affordable and I had an entire pottery studio in the basement. What I had been asking for just fell into my lap. So I started hand-building. And I felt grounded again, in a way I had once felt when I was making photos.

When the Biden election happened, I got blindingly angry. I had to do something with that energy. I started playing with natural ink. I was making coffee, grinding that ink with some other stuff, and I just started drawing. It was helping me get the energy out. I asked myself, ‘What would I do if I wasn’t concerned about making money?’

Long story short, I fell into this new practice—works on paper, ceramics, and sound—where language itself became a medium I was using. And it had been there the whole fucking time, but I couldn’t see it because of photography. I had been laying down the groundwork for the practice without even realizing it.

So full circle, the moment I put ink to paper, I just knew: ‘This is it.’

Angie: Have you worked on any editorial jobs since you moved to Chicago and left the industry?

Oriana: I’ve had really exceptional experiences working for the Chicago Reader. The writers are exceptional. The editor-in-chief is exceptional. The moral clarity that team carries is beyond anything I had experienced before.

I documented the cover story they did on Black femme sex workers post-pandemic. It felt so good to hand someone my work and have them engage with it deeply enough to know I could handle that variety of assignments. That had not been the case when I was doing editorial before.

When you work at the level we work at, everyone is making excellent work. What distinguished me is that I like to run my mouth and I can speak in coherent paragraphs. That has always been my strength, which I now realize is directly connected to my disability. I’m hyper-verbal, autistic.

I will never stop making pictures. I’ve been deeply invested in a vernacular photography practice because I’ve been thinking a lot about archival practices Black people have that we don’t always see as part of ‘the archive’—because we’re not given that language.

But I grew up looking at my grandma’s family album. That was the first seed planted for me. And it was also my grandpa’s collection of National Geographic magazines.

Angie: At this point, would you accept editorial assignments?

Oriana: I would’ve said yes prior to the election. Now I say no. The media landscape and its acquiescing to the dismantling of a free press is frightening. It puts journalists—visual or otherwise—at deep risk.

If there’s anything I’ve learned in the time I’ve been away from photography, it’s that it’s intolerable for me to have to put aside my ethics and my values. I can’t do it. I was jumping through hoops in my head around visibility and representation, telling myself, ‘These stories need to be told. These people need to be seen.’ And I do believe that’s true. But I also know that doesn’t change the material realities of the vulnerable people I was photographing. That’s a hard pill to swallow, because part of the reason we all do this is to change lives and change minds.

I think there are some things that are deeply important to consider. We’re in a crisis of conscience and a crisis of critical thinking. Pretending that what we’re living through does not have dire consequences for all of us is something I cannot participate in anymore.

It’s crazy to me for anyone to be like, ‘Okay, what’s the hottest restaurant?’ They are literally disappearing American citizens. I don’t want to talk about restaurants. I don’t want to take pictures of celebrities. How long do we do this until we can’t do it anymore? The apathy right now is truly frightening to me.

So no, I will not be picking up my camera. But I will be picking up my pen instead, because I think that actually has more power right now. I think truth-telling is an antiseptic to fascism. Artists are the ones who say, ‘This is not okay. It can’t be this way.’ That is supposed to be the role of the media and journalism.

I would not make money in this climate as an editorial photographer. I am a liability—and I’m really proud of that, actually. I don’t want to be seen as safe or as someone who would capitulate at this moment. That’s not my job as an artist.

I am the happiest I can remember being in my adult life. Every day I wake up engaged in work that is deeply meaningful and important to me. I’m not having to pretend to be palatable or behave a certain way, which is intolerable when you’re autistic. If something is wrong and makes me physically uncomfortable, I cannot deal with that, and it’s very difficult for me to pretend otherwise.

Angie: That’s a superpower. But I can also imagine it being really, really hard.

Oriana: We know how to communicate with one another and not take things personally. The fact that I get excited about believing that injustice is not something anyone should have to tolerate—that’s one of the things that makes me the artist I am. It was also the reason I was able to make photographs the way I did.

More than anything, seeing that you can have a successful career and walk away from it is probably the most deeply empowering thing I’ve done. To know that you are worthy in and of yourself, exactly as you are. That worth doesn’t need to be quantified by a paycheck. It doesn’t need to be quantified by marriage.

All of the times I was told I couldn’t survive—I have survived. And I’m thriving.

I think practicing bravery and courage is actually a deeply important practice. We don’t have many avenues to practice courage in the United States. I’m also seeing that a lot of cowards are running around, and it’s just because they don’t know they already have the power within them to be courageous. The powers that be don’t want them to recognize that.

If you decide to leave the photo industry, for whatever reason, that’s not a failure. You get to pick the life that makes you happy. And anything in your life that doesn’t make you happy—get rid of it. It’s not worth it in the end.

We have a very, very short time on this earth. If you don’t do it now, when will you do it? Just take the fucking leap. You’ve got nothing to lose and everything to gain.