It’s been a crazy week.

Out here in Taos, we hosted a Bar Mitzvah for my son, (on the second attempt,) and people flew in from around the US.

I was apprehensive, as the Delta variant has brought America back to its knees, and we were terrified our daughter might get Covid. (She’s too young to qualify for the vaccine.)

But cancelling wasn’t an option this time around, so we soldiered on, kept things outside as much as possible, and hoped for the best.

I catered a dinner for 30 people, the first night of the event, and after years of running our Antidote photo retreats, I got it done without too much stress.

Sure, one of my pans caught fire while I was making teriyaki chicken, but luckily, I put it out, and no drama ensued.

It was a tremendous amount of work, but we wanted to honor Theo’s commitment.

Because that’s what we do for our kids, right?

We sacrifice, and give our all to the endeavor, as raising human beings in such a complex world is the biggest job a parent has.

Thankfully, it all worked out in the end, and everyone had a good time.

It was challenging, but pales in comparison to what others have dealt with this very same week.

(I think you know what I’m talking about.)

Back in college, when I studied Political Science as a freshman, it was conventional wisdom the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan brought down their Empire.

(That was the word on the street.)

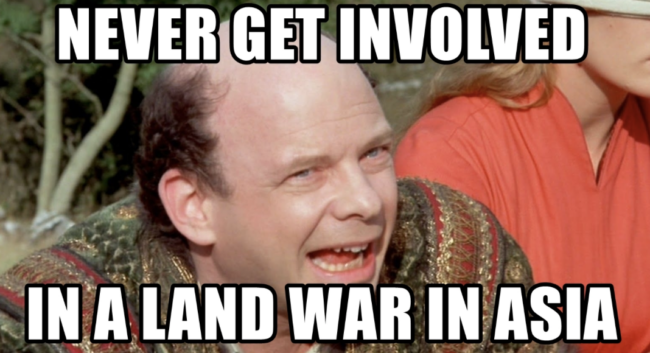

Just like Wallace Shawn gave us the famous quote, “Never get involved in a land war in Asia,” everyone knew Afghanistan was an unconquerable country; a quagmire where great powers went to die.

And yet…

When Osama Bin Laden and his asshole buddies attacked the US on 9/11, we backed the proxy army of the Northern Alliance, and then basically took over Afghanistan.

That was twenty years ago.

It’s hard not to imagine how those trillions of $$$$ might have been spent here: universal health care, free college, homes for the unhoused, a Green New Deal.

Who’s to say what might have happened, if things had gone another way?

But they didn’t, and this week, America’s failure to build a stable government in Afghanistan was all over our screens, in every form imaginable.

Twitter, FB, TV, IG.

It was a cluster-fuck of epic proportions, and avoiding the news was impossible.

Such travails we have over here, as we worry about ingesting too much “traumatic imagery” for our mental health.

If only the Afghans had problems like ours.

(But they don’t.)

The Afghan people, or many of them anyway, are too busy running for their lives.

They don’t have the luxury of worrying about the negative ramifications of traumatic imagery, as the misery they see is in front of their ACTUAL eyes, without the mediation of an iPhone screen.

It’s nasty business, what they’re living through, and honestly, I hope to never endure something like that.

The people of Afghanistan have my empathy, and all the “thoughts and prayers.”

To face the realistic fear my family might be annihilated by bullets, bombs, swords or stones does not compare to worrying whether I’ll overcook the lasagne.

(I didn’t, though. It was delicious.)

The world we inhabit is insanely unfair, and the place you’re born ultimately has more to do with what your life will look like than any other indicator.

Here in the US, the difference in neighborhoods in the same city can have a massive impact on life expectancy, health outcomes, and income.

Still, almost everyone in America has a safer environment than those living in impoverished, war-torn societies.

People in places like Afghanistan, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Syria, and Yemen face obstacles we simply can’t comprehend.

It’s not possible.

(And notice I wrote “almost” two sentences ago, as there are some US residents living in very dangerous situations.)

At times like these, Art is most helpful, as it allows experiential information to be transmitted from one life to another.

Artists can share their POV, and viewers benefit from receiving the stories we read, see and hear.

That’s how it works.

Hell, just two weeks ago, I wrote about the necessity of those photographers who “bear witness” in the chaos of the 21C, as there are now phones with video cameras to capture everything that happens.

Frankly, that’s my only hope for Afghanistan, small though it may be.

Short of shutting off the internet, the Taliban will face a wave of recording technology this time around that didn’t exist at the turn of the century.

It’s at least possible the Taliban will be somewhat restrained by images and videos of their atrocities reaching the global pubic.

(It’s not much of a hope, but more than nothing.)

Again, it’s easy to for me to sit on my chair, put my feet up, and write this column for you.

I have the privilege of safety.

And all the smartest people are telling us a global refugee crisis is just getting started, as Climate Change will render some places uninhabitable, (where people currently live,) and then a lack of vital resources, like water, should kick off more drama.

It seems the refugee phenomenon will overwhelm our current system of borders, paperwork, passports, and institutional infrastructure.

(Come for the photography review, stay for the futurism.)

That being said, you can’t have a book review column without a book, and you might guess where we’re going today.

It just so happens I had the PERFECT thing in my book stack for a week like this.

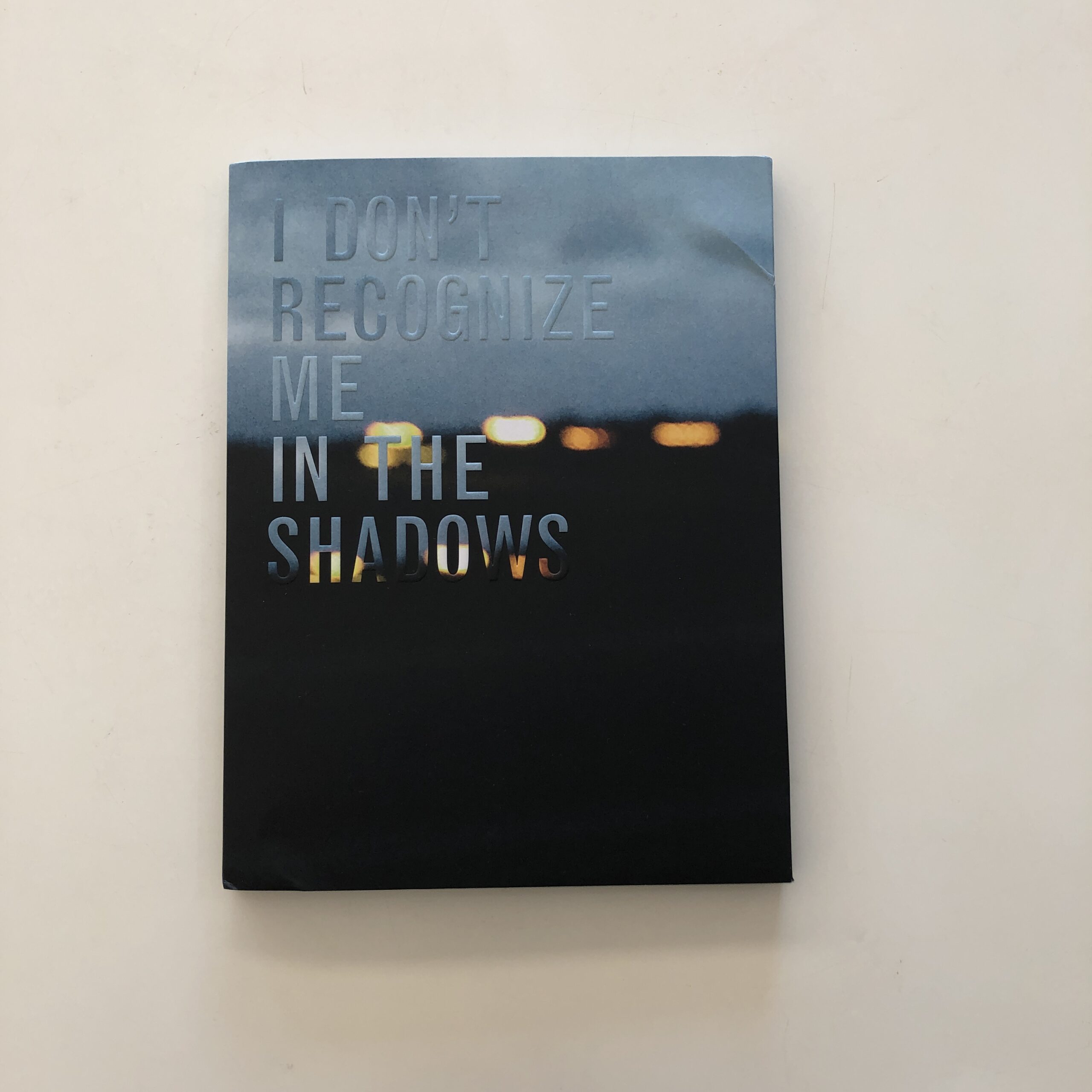

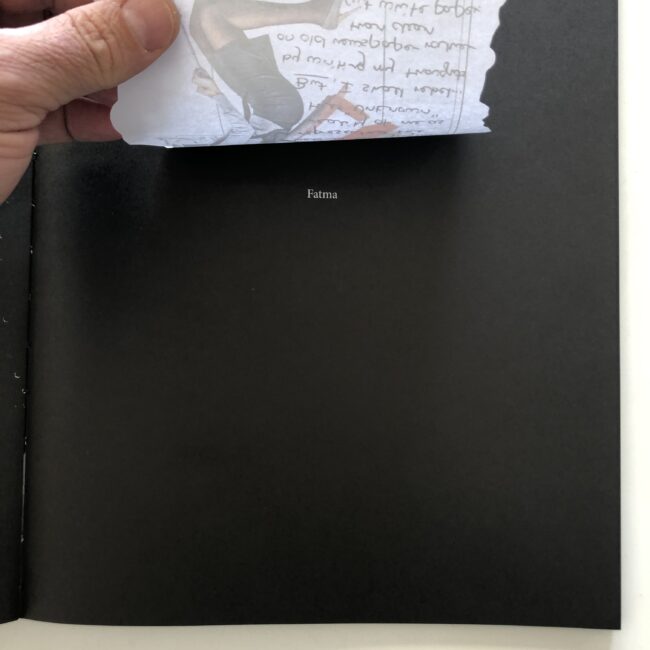

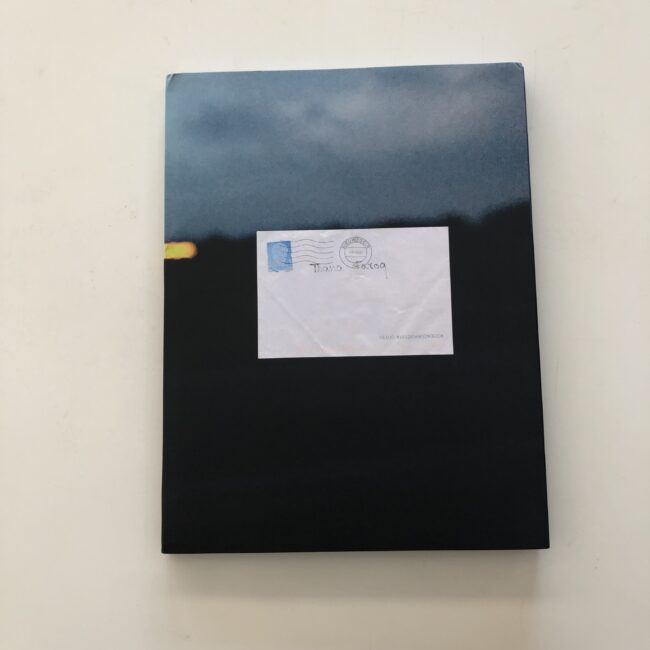

Earlier this year, I received an email from Thana Faroq, a Yemeni refugee living in the Netherlands, who asked if she could send me a book, “I Don’t Recognize Me in the Shadows,” published by Lecturis, with support from the Open Society Foundations.

I was flattered, and happily accepted her offer, so let’s dig in, shall we?

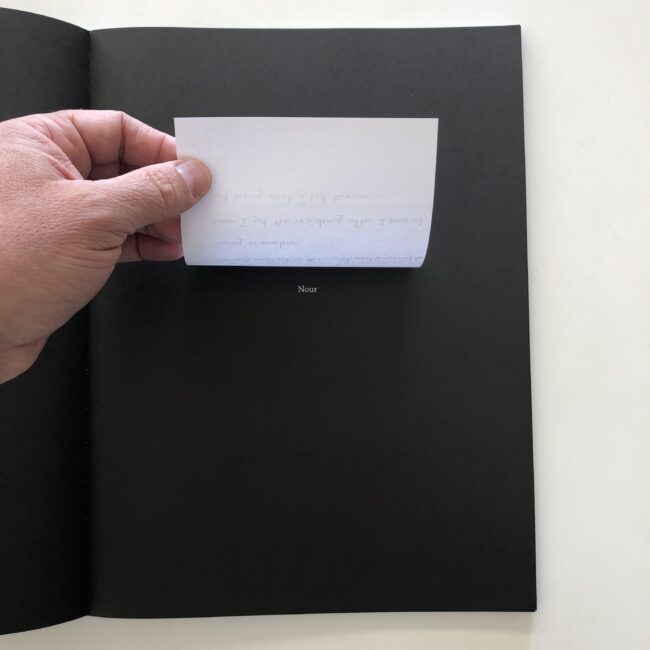

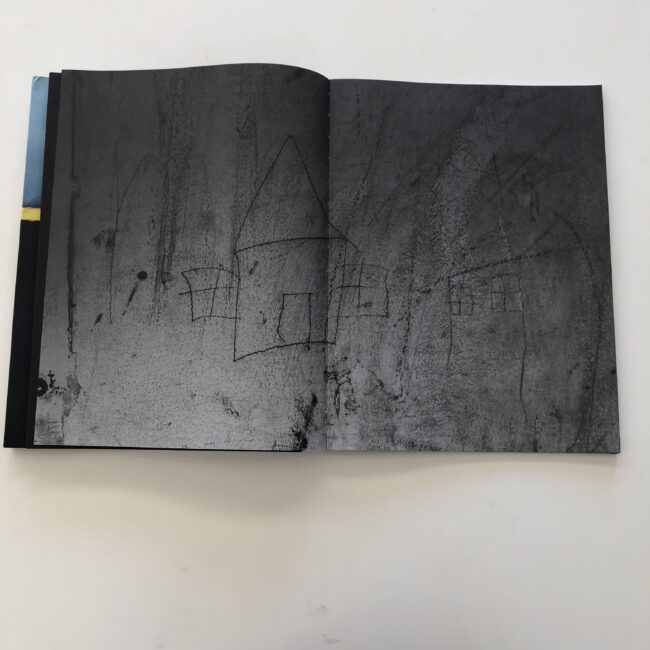

It took a minute to figure out how to open the book, and then how to make it work.

The cover wraps around, and you have to open it a few times to get a sense of the object, but then it functions like a traditional publication.

(Turn the page, see something new.)

Certainly, I hadn’t considered how much the interminable periods of not-knowing-what-comes-next would be so maddening.

As we flip through, we learn about the constant waiting on paperwork, on status updates, on hearing from some bureaucrat whether you can stay safe, or if they’re planning on sending you back to Hell.

Can you imagine?

That’s why books like this are so helpful, as empathy differs from sympathy in its requirement that we put ourselves in others’ shoes.

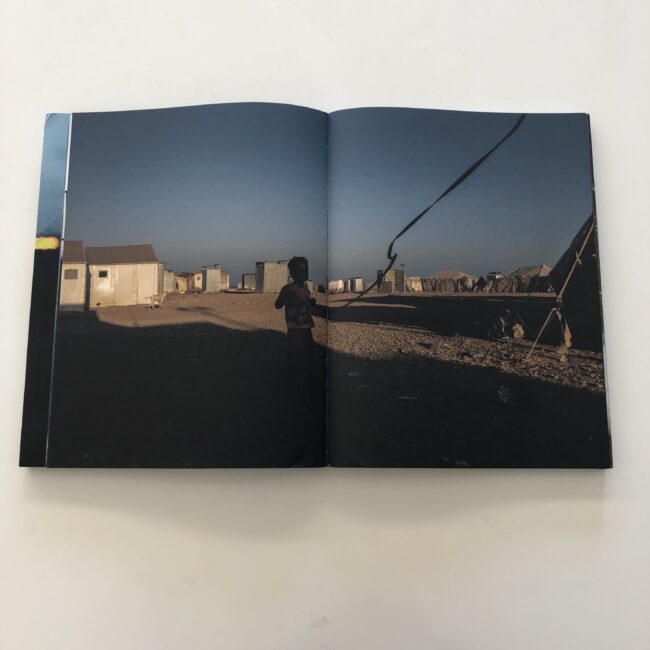

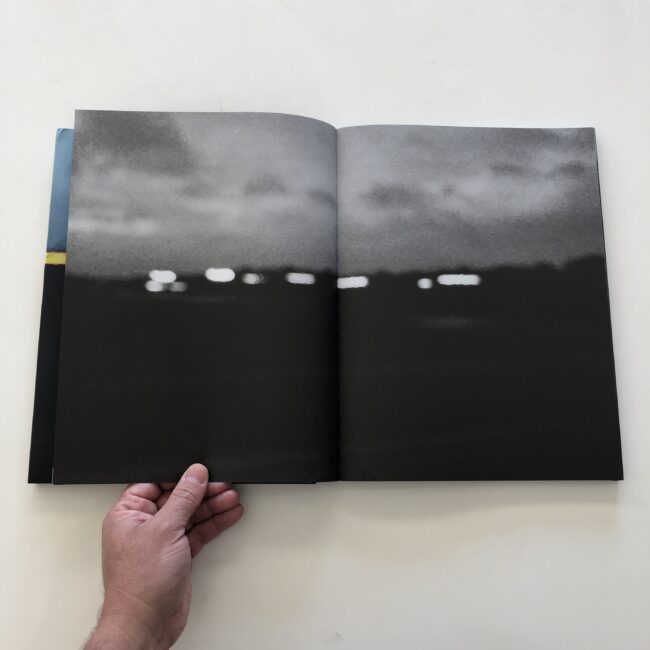

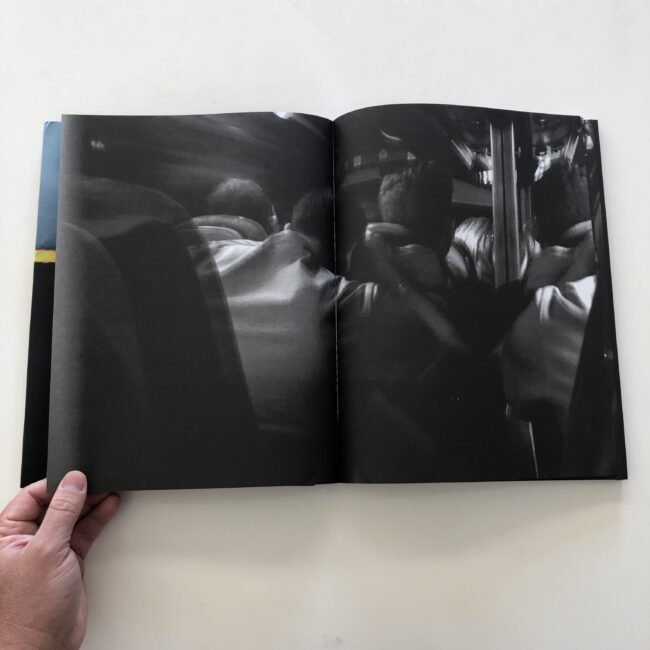

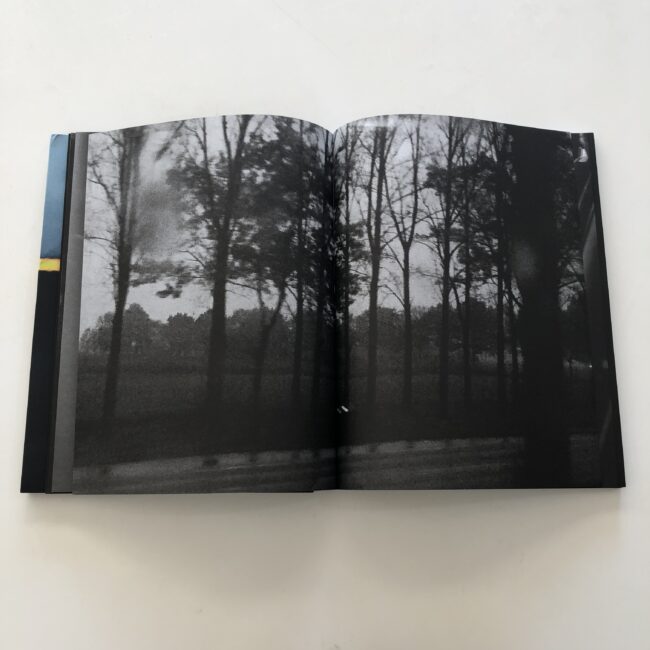

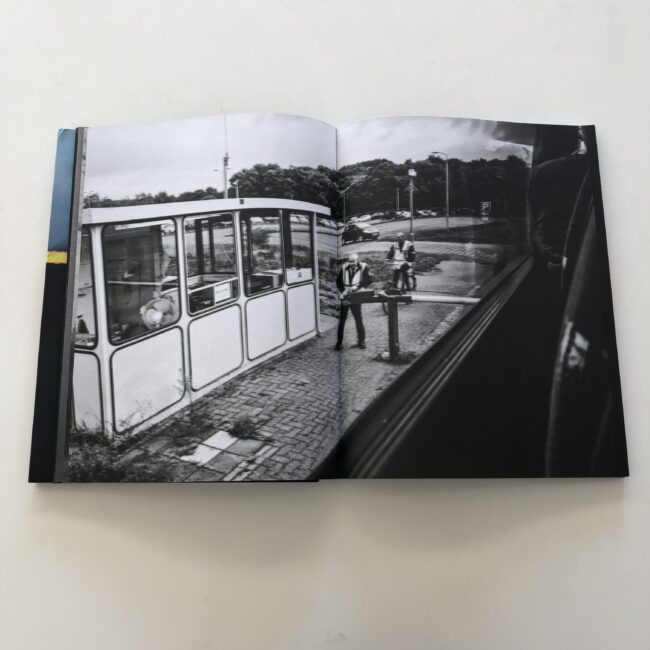

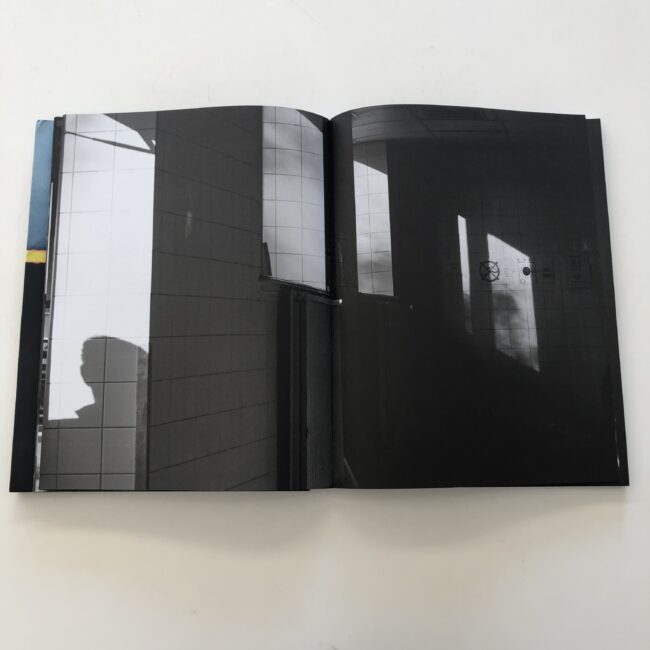

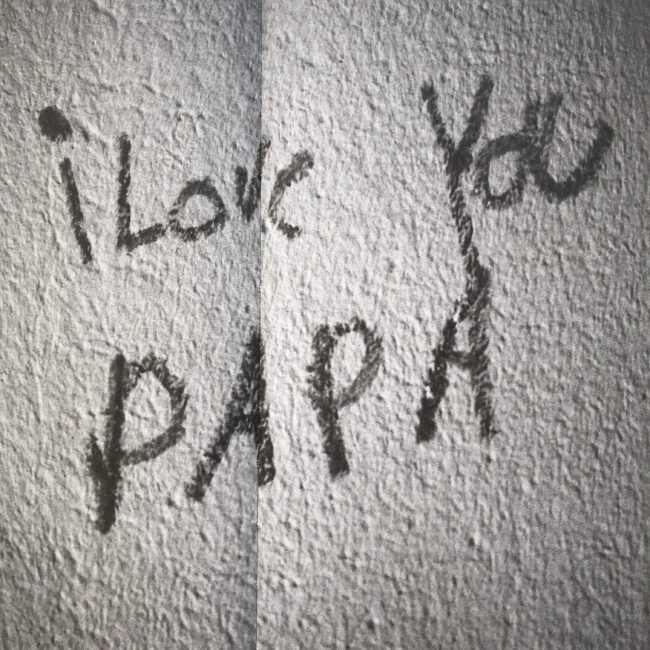

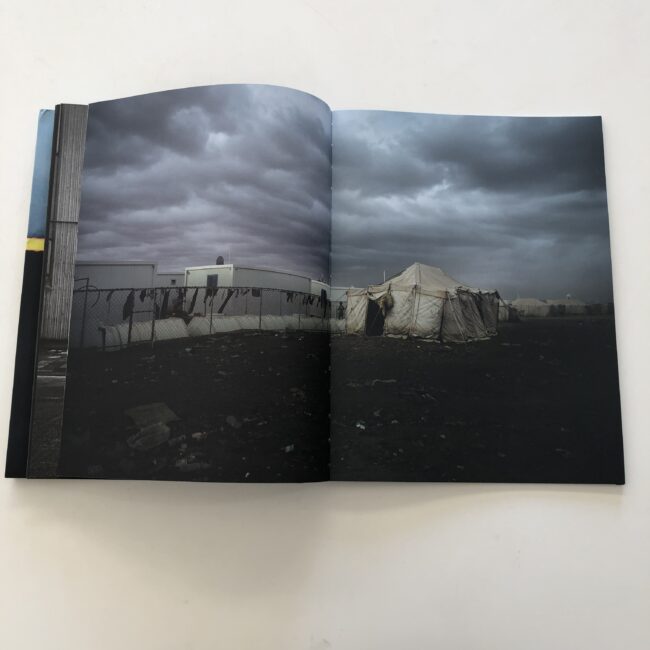

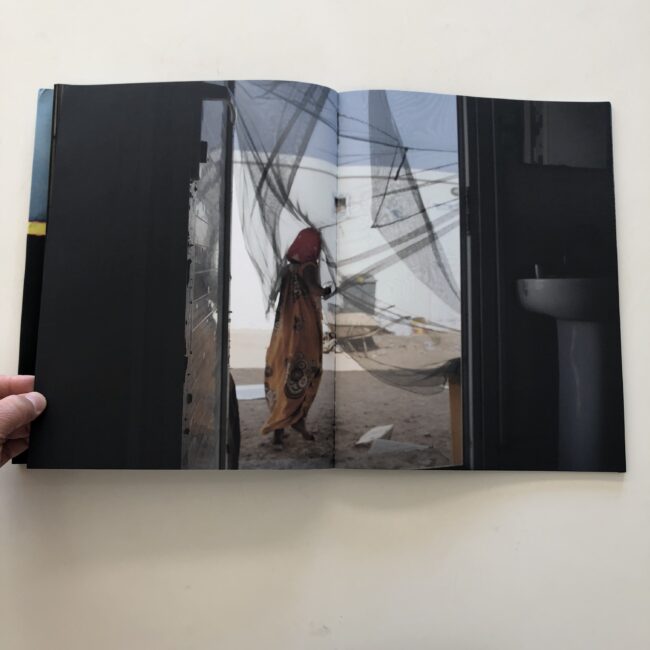

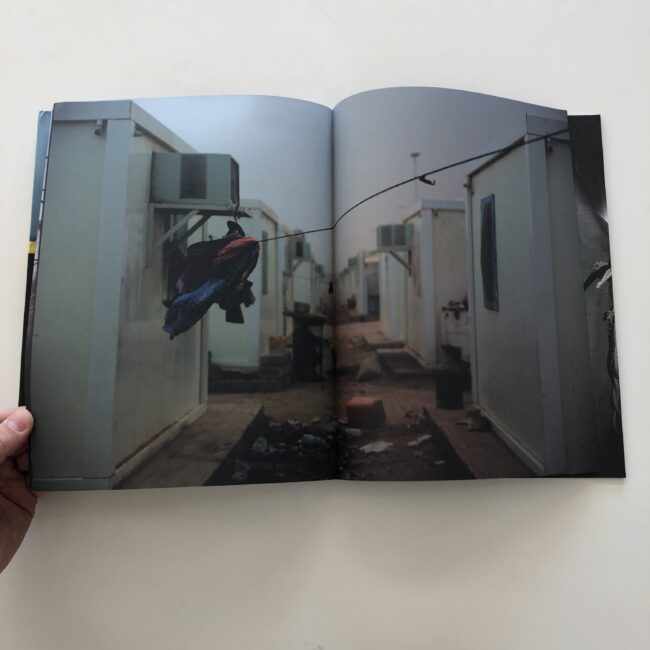

The book is experiential, as after the opening text, we see a set of color photos made in a refugee camp in Djibouti, but then it goes Black and White, until another set of color photos at the end.

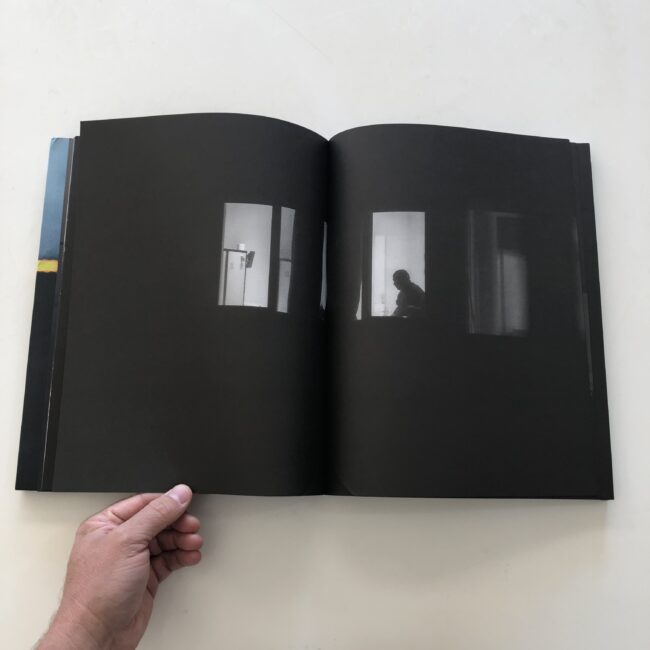

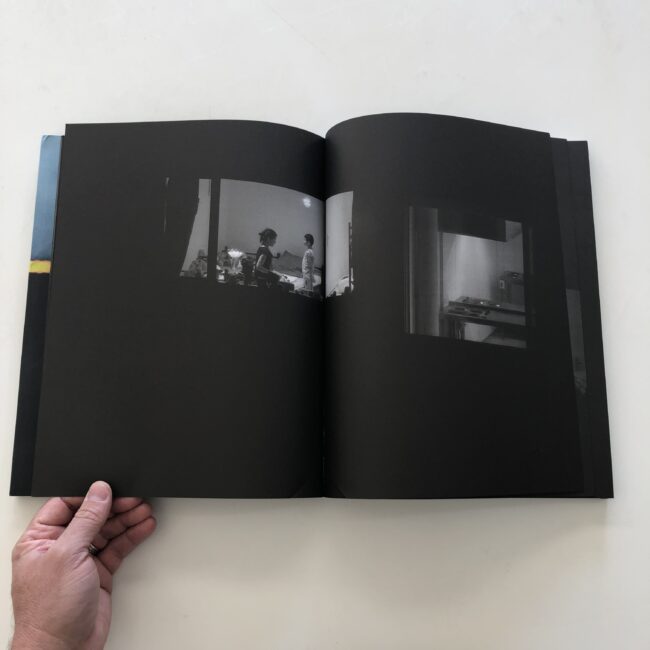

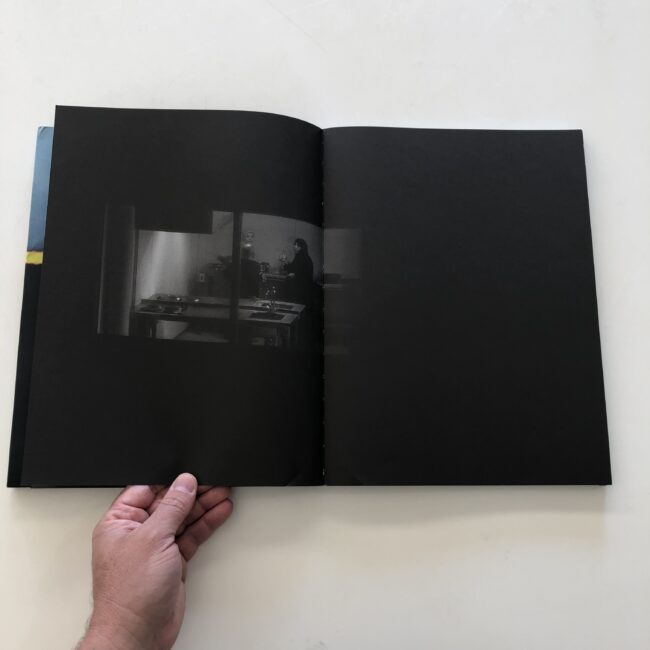

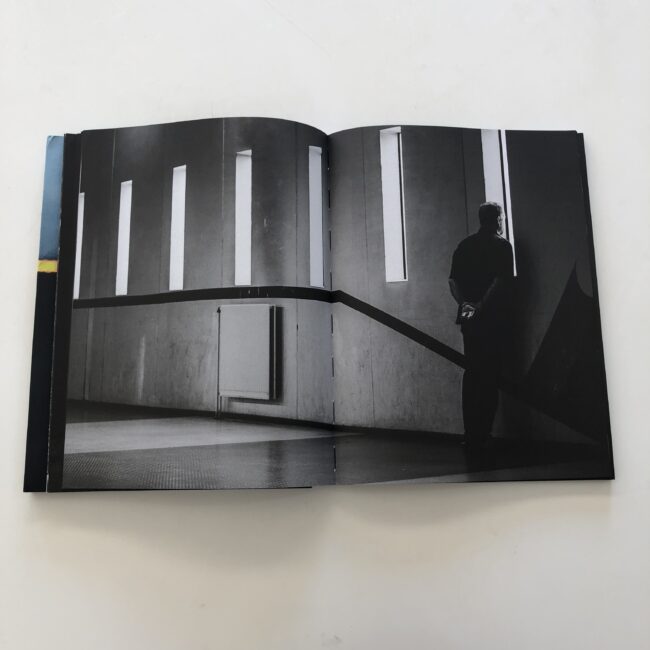

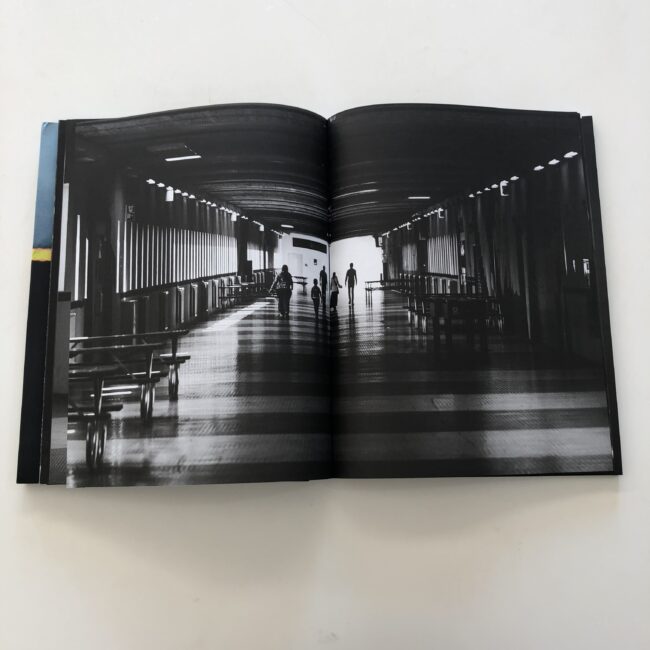

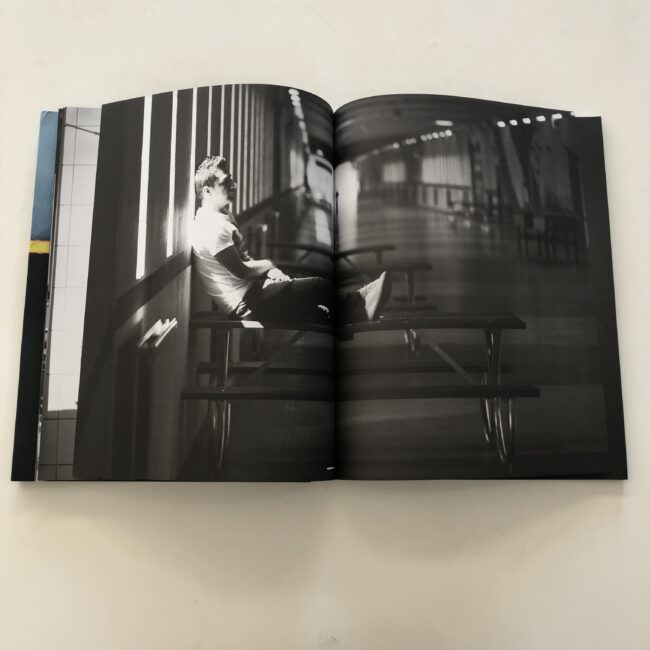

We see page after page of people in apartment block windows, standing around.

At first, I was confused, and then realized, as they built upon each other, it was a metaphor for standing around, waiting, looking out the window because you have nothing else to do.

We see photos out bus windows, walking down institutional corridors, and little moments that give a sense of the banality of fear.

(These people are safe, temporarily, but until the permits come through, it’s purgatory.)

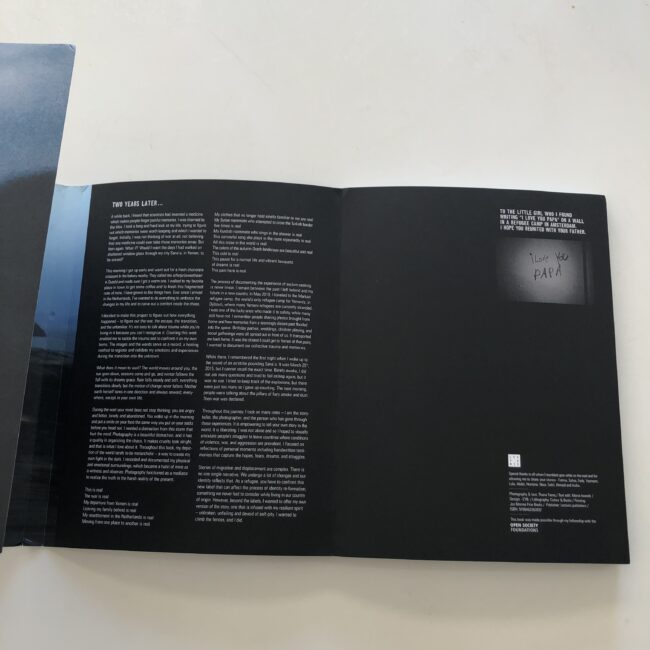

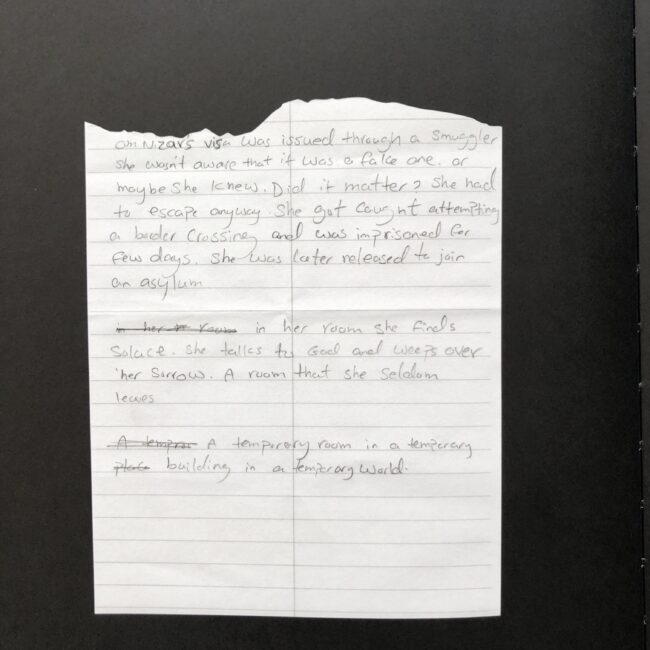

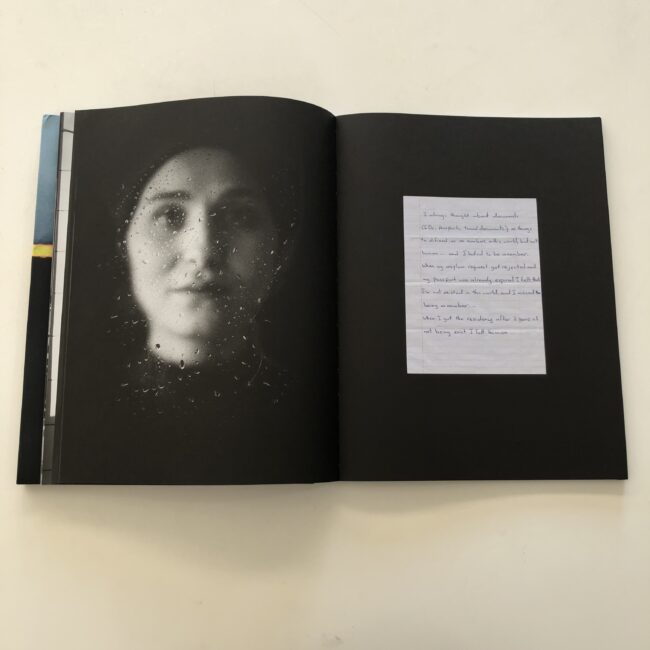

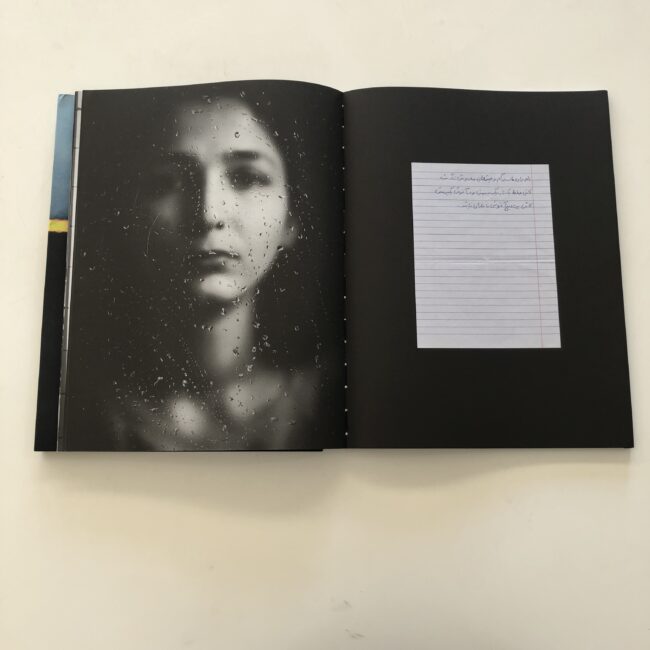

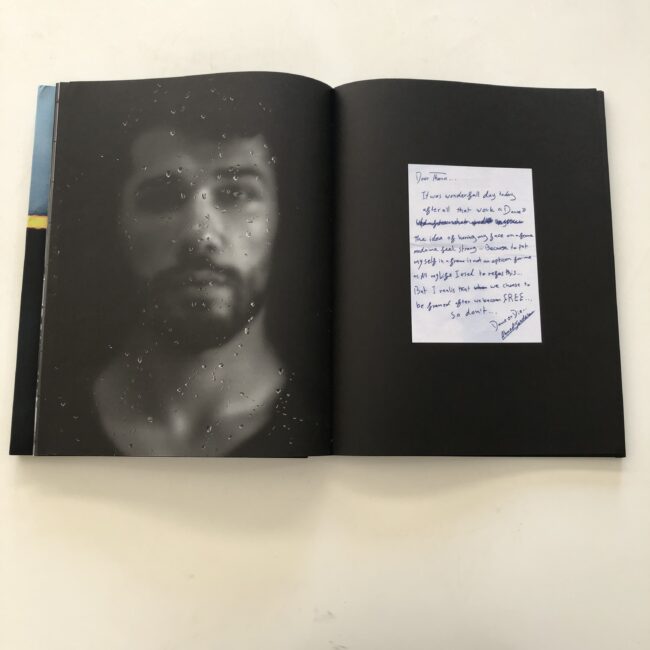

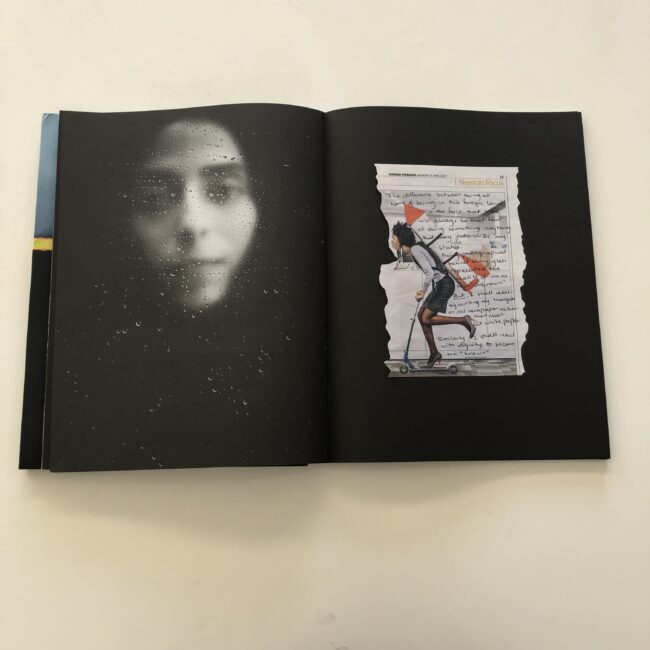

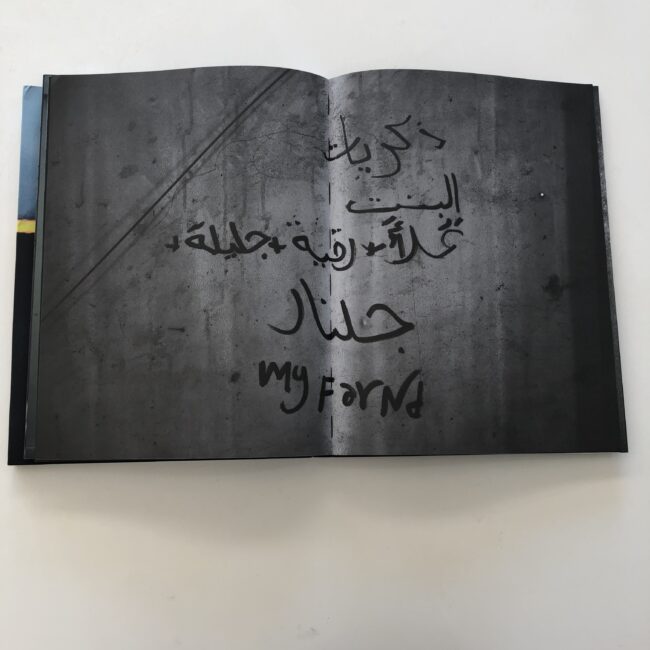

Then, in the book’s middle section, we have portraits of refugees, taken through blurry glass, perhaps to protect their identities.

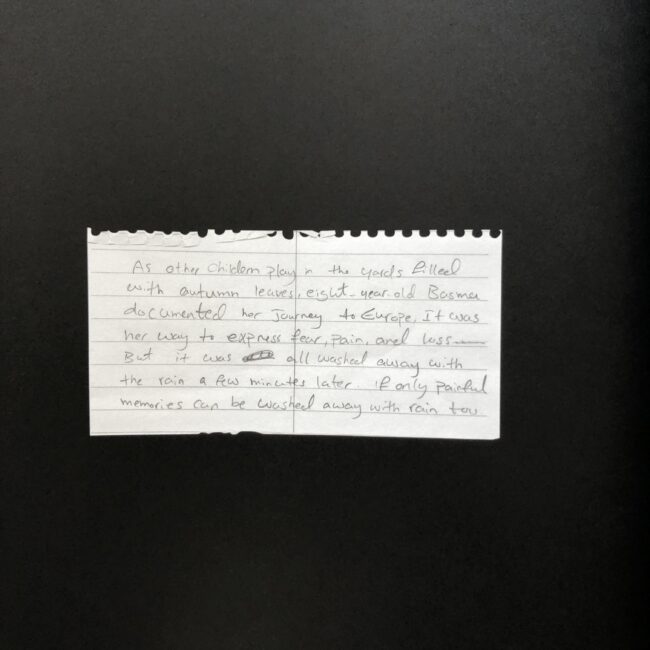

And those are paired with their hand-written-type statements on pieces of paper that have been glued to the page.

As I wrote when I reviewed Katherine Longly’s “Hernie & Plume,” or Maja Daniels’ “Elf Dalia,” it seems the European-based book artists have a great sense on how to break up structures to prevent boredom, these days.

When I turned the last page, I felt grateful as much as empathetic.

I appreciate the bravery it takes to stay present in such difficult circumstances, and offer evidence to the rest of us.

So, thank you, Thana!

I hope you stay safe over there.

And when you get a chance, make sure to check out the pan-fried noodles at Kam Yin in Amsterdam.

The best!

To purchase a copy of Thana Faroq’s book, click here

1 Comment

How does that saying go?

“The worst is yet to come.”

Comments are closed for this article!