Manjari Sharma

Manjari Sharma

Heidi: How has your relationship with the work changed if at all since moving to the United States?

Manjari: It’s been an incredible journey, and one I wouldn’t change anything about. I came here to the USA at 21 and looking back I knew very little about the “history” of America. What I did know was I was going to make a lot of pictures, meet a lot of new people and ask a lot of questions. I wanted to grow and that curiosity led me across the globe. My relationship with my work over the years has become more intimate. I am more transparent with my practice and I think it’s because simplicity and complexity in equal parts are inextricably tied to aging. Time is certainly the best teacher. When I was younger things were more black and white and now I know there are multiple realities to most all stories. When I was younger I was honing my craft, and then I started telling my own stories. This is where my path changed, where the story became so important that it had to be told at any and all costs. It didn’t matter who was publishing the work or inviting it for a show. The work had its own preordained path and it had to be born.

As you gain distance, is it reinforcing something for you?

Gaining distance from that which we love is a double-edged sword. At twenty one I knew or cared very little about the duality of stepping away from my home and my family. The sense of adventure and the draw to pursue and carve my own unknown path was so strong, I wouldn’t have it any other way. I am fortunate that my family supported my unbridled wishes. Over the years I have both learned and unlearned a great deal about both my Indian descent and my adopted American culture and they are bittersweet truths. What this distance or as Pico Iyer calls it the “Gift of exile” is that it has allowed me to do is make up a culture of my own; A hybrid identity that draws from both these incredible countries that I am fortunate to straddle.

What marked a pivotal time in your career here in the US?

2008-2013 I photographed a series titled The Shower Series. I invited people I didn’t know very well to take a shower in my shower as I photograph them. The premise was risque and clothes were optional. I photographed a plethora of people showering and ended up having these unexpectedly disarming conversations with them. The water became a conduit and almost every single time I photographed someone, I felt entrusted with a really personal story. I made audio recordings of the protagonists’ short stories with their consent of course, and they were so honest and beautiful. A shower is such a sacred space that our intimacy and the cleansing aspect of water turned the experience into a really meaningful connection. I won’t lie I felt like I fell in love with every one of my subjects. I also found myself quite consumed by the process of making this work. I was addicted to hearing these raw and vulnerable stories because they turned my subjects into these complex, powerful characters that had so much depth. Somewhere during these sessions, several portraits were taken; My lens got fogged, my toes got wet and the photograph became a reason to connect to something beyond. This series was a pivotal point in my practice because I realized the camera had become an extension of my personality. Meeting a new human being, learning who they are, what takes them down, what makes them tick, is was what brought me to another country. So much of that series was a discovery that the lesson I learned here was to pay attention and follow the lure of my unconscious mind.

Now that you have lived almost half of your life in India and half in the US when you created this work, which part of you did you relate to the most?

Now that you have lived almost half of your life in India and half in the US when you created this work, which part of you did you relate to the most?

When I look at my work I see a pluralistic lens. I am guided by American inquiry but I assess my work from an inner core that is rooted in Indian culture. Many of these experiences of growing up in India I am present with on a daily basis, and then there are others that time has made opaque, yet, I know they are deeply embedded in my inner landscape. The best example of this might be like the lyrics of a Hindi song that I forgot I knew verbatim. As an artist never losing sight of this unknown murky middle ground that lies between the known and the unknown is probably my most challenging yet rewarding part. Mining that cerebral interlude for answers is what I derive my greatest satisfaction from.

Are you talking about the lyrics to a particular song, why do you think it resonated?

Recently I was at my friend’s house Sarita, and she played a Hindi song I hadn’t listened to for a really long time, maybe even decades, but I found myself knowing it word for word. My palette for music was a gift from my mother. I specifically remember moments when she shook her head and wiped her tears because the melody and lyrics of a song could move her so much. The songs that had meaning to her were played and overplayed in my home. I listened to Indian music on my mom’s Panasonic cassette player and she exposed me to such terrific names RD Burman, Naushad, Mohammed Rafi to name a few. Anyway, I’m digressing I am using this as an analogy to share that formative experiences from 21 years in Bombay are burned and embedded into my psyche. I’m shaped by these and so is my art.

Fabric in general holds a lot of meaning for me. Indian customs, rituals, and relationships are symbolically represented by color, textiles, and knots in an immense way. The act of tying and untying has great relevance in Indian culture. A knot represents a promise. The act of who ties a knot between the bride and the groom at an Indian wedding for example has ancestral significance. As a young woman, the Saree to me was regarded as a garment that commanded respect. I remember staring at my mother when she draped herself in one. Wearing a saree was an occasion in itself and from that perspective, as a young woman, I romanticized it. Walking gracefully in a saree took practice and poise and an improperly tied saree was not only sloppy but dysfunctional. In that sense spending time with folding, pleating, and draping nine-yards of fabric was a meditation in its own right. As an adult, I look at it a bit more microscopically because as life would have had it my mother (a dementia patient) can no longer drape herself in a saree. Also as I examine India from a sexist lens, I look at the saree not just as a delicate decorative but also as a symbol of patriarchal control. I have a deep and spiritual admiration for this garment, but I also critique it as a modern Indian woman. I had a teacher in a college in Bombay and her name was Putul Sathe she was a counter-culture spitfire who imbued me with radical liberal thought. The saree is incredible and incredibly limiting and I wanted to address both those aspects in my series “How to wear a saree”

What was the tipping point for your recent letter titled “Love Letter to America?”

George Floyd’s death in particular shook me to the bone. “Love letter to America” as you know weaves my own experiences into the fold but what began with “Talking Pictures” came to more honest fruition with Love Letter to America. You can read it here

“Talking Pictures” was influenced by the 2016 elections, so here we are 4 years later, how has this current landscape informed your work?

Talking Pictures was an assignment through The Metropolitan Museum of Art and a big subject of that commission became the growing life inside my body as I discovered that I was pregnant during the course of the assignment. However, the outcome of the election, and particularly Donald Trump’s win was something I had to address as part of my work. Trump’s win was the first time I found myself traveling to DC on a bus at 4 am to exercise my rights and protest against the disturbing political landscape of America. I understand that we are bipartisan as a country but I have known, befriended, and even loved many republican leaning Americans. However, Donald Trump represented an America that was at odds with everything I understood and respected about this country. I am brown, grew up in India, and over the years my understanding of racism and white supremacy has grown steadily but Trump’s America permitted behaviors I didn’t realize this country was capable of. This speaks to my privilege of course, but my art practice could no longer ignore that I needed to headlong address certain racist inequities that I now found myself shielding.

There is so much expression of life in the streets of India, are you drawn to mural work?

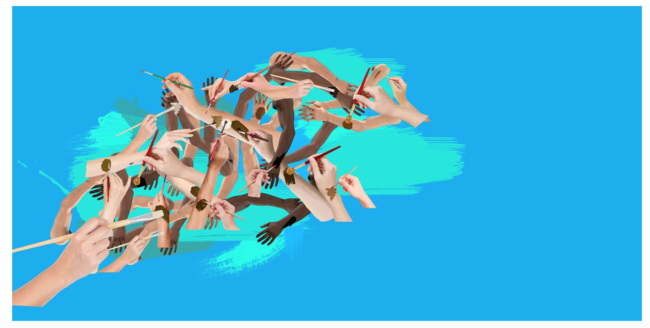

Yes public art was vivid in Mumbai and I certainly have a sense of belonging to it. With galleries and museums being shut down due to the Coronavirus pandemic, Public Art and the vitality it brings to communities is more important than ever. This mural, A cacophony of human hands rising like a wave, is also an extension of a recent piece I wrote “Love Letter to America”

What does it mean?

Sometimes we don’t see people for what they are, we see them for who “we think” they are. Are we programmed to misunderstand each other? Can we fight this programming? The purpose of the mural is to invite the viewer to examine and self-reflect on our racial lens and actions as a community.

I know you’re on the board of the organization Art Bridge, an initiative that helps early-career artists have a brilliant platform. Tell us about this piece “Simultaneous Contrast” pictured above, in a sketch and a comp.

Simultaneous contrast is a new body of work I’m only just beginning work on. Much like my series Darshan it is currently a sketch and is yet to be constructed. It is based on a phenomenon rooted in color theory. Simultaneous contrast is a term that refers to the influence of one color when in close proximity to another. The theory is that when placed side by side, one color can change how we perceive the tone and hue of another. In reality, the colors themselves never change, but in our recognition, we see them as altered. No normal eye, not even the most trained one can see color independently. This series is an exercise in challenging the framework of our consciousness. What does the color of our skin represent in society? What is our role in shaping the perception of colors around us? Simultaneous Contrast invites the viewer to examine the illusion of stereotypes, and question our role in altering the perceptions of implicit bias.

Artbridge has an auction up for about a week and people have the opportunity to grab amazing art. You can buy this piece from my series “Surface Tension” to support this incredible organization or browse some amazing other artists here.