Photographer: KR Sunil

Home (Images 1,2,3)

Vanishing Life Worlds (4,5,6)

Manchukkar: The Seafarers of Malabar (7,8,9)

Heidi: How did this idea of “Home” come about, which was your first image, how did that inform the series? How long has it taken to photograph this body of work?

KR Sunil: I hail from Kodungallur (the ancient harbour town Muziris which was a significant presence in India’s port towns and trading history). So I have grown up closely related to the coastal life in this historical region. As a photographer, I have spent a considerable number of years with various series related to the sea.

The idea for this particular series (‘Home’) occurred to me following an incident while I was working on the ‘Vanishing Life Worlds’ series in Ponnani (another port town). I photographed a thatched home of a young girl by the sea, which was on the verge of collapsing. On circulating this photo, few friends and well-wishers stepped up to rebuild this home for the girl. And they did too! But unfortunately, the renewed home too collapsed under the force of the tides in some time. This was the inception of the series for me, as I began to observe a growing number of desolated homes by the coast. For me, what struck was how hard-hitting this was for the people, as ‘home’ is a deep sentiment for them; it is much more than a shelter. For many, it is a lifetime’s endeavor to build a home. It is literally a dream come true for them. Also, for a close-knit community as theirs, the concept of home extends to the whole environment they live in. There are neighbourhoods, religious places they frequent and a camaraderie that they have to leave behind when the sea takes over. This encroachment by sea can be attributed to worldwide climate change and phenomena like global warming. But the unfair part of it is that these communities barely contribute to causing these. In fact, they are a community that holds utmost regard and respect for nature, to the extent of calling the sea ‘kadalamma’, which translates to ‘mother sea’. Yet, they’re forced out of their own homes by the same sea. This has been a growing effect in recent years, especially in the coastal regions of Kerala, which includes my hometown too.

Do you know any of the homeowners affected by this climate event, or do you know where they migrated to?

I have known a few of the families that were forced out in recent years. Not personally up close, but I would’ve seen them during my visits and walks to their localities. Now only remnants of their homes are seen there. They have been dispersed to different places – near and far, but safer. They have to then spend uncertain number of days (many of them in rented houses), pondering about the home and community they have had to leave behind. As far as they are concerned, this shift to a safer place is not a resolution; they are only left with an angst about their home.

What draws you to the sea?

I have spent a good part of the last 5-6 years on various series related to the sea. ‘Vanishing Life Worlds’ was a photographic series based on the lives of people at Ponnani, an old harbour town in Malabar coast. It was exhibited at the Kochi Muziris Biennale in the year 2016. SImilarly, ‘Mattancherry’ was a series about life at another port town Mattancherry in Kochi. Then there was a series on the last surviving group of seafarers of Malabar, titled ‘Manchukkar – The Seafarers of Malabar’. This text-and-photographic series narrated the stories of men who worked in traditional dhow (or uru) and endured painstaking lives. Another series is in development right now, which follows the life of performers of Chavittunadakam, a dying artform that survived through the coastal community.

So to answer you, I’d like to point out that it’s not the sea that draws me, but rather it is the lives related to the sea that drives me.

Port towns have a unique history of having welcomed and accommodated people from all parts of the world. The people of these towns get a better sense of the world, thanks to the visitors. This has defined a broad-minded trait in these people about life, which I believe is universal for coastal or port town communities. For instance, while visiting the port town of Ponnani, I came across Abubacker, who I’d describe as one of the finest personalities I have ever met. Operating from an abandoned go-down facility, he sources and gives out free medicines to the needy – medicines worth thousands of Rupees on a daily basis! And this, without seeking any recognition or returns. In the same town I have met people with varied traits and vocations. Like Asees, who was a pick-pocket but known and familiar to everyone in the region. (Sharing a video by Kochi Muziris Biennale featuring these personalities, for reference –

I always found these people fascinating – they even have a glow on their face which I believe is attributed to their positive approach about life. So these lives appeal to me rather than the sea itself…

For “The Seafarers of Malabar” how much time did you spend with each subject prior to bringing out the camera?

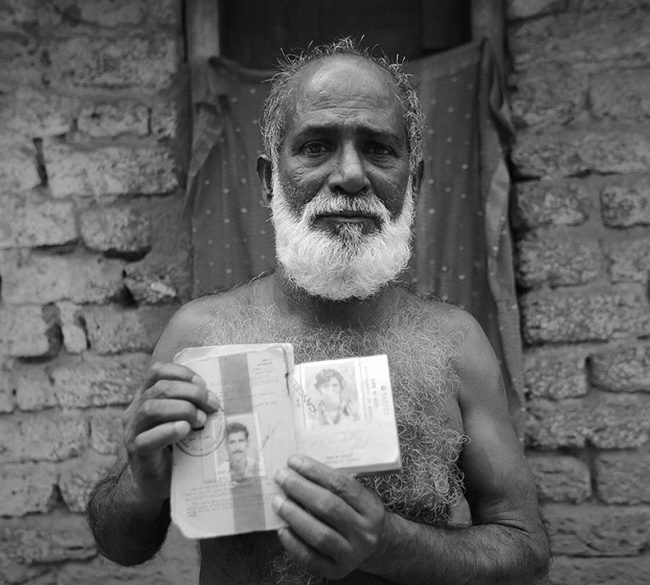

The series occurred to me in a rather coincidental manner. I used to frequent the port town of Ponnani and interact with the people there. On one occasion, I came across Ibrahim, a very elderly man, who was singing a folklore about life at sea. I was intrigued by his rendition and listened to him for some time. When I started talking to him, I realised he was a seafarer in his youth. The more I spoke with him, the more fascinating his story grew into. He used to work in the traditional uru (or dhow ships) that carried out trading between port towns. He had spent his prime travelling around the world! I couldn’t have been more excited. He ended up inviting me to his home, where we sat and talked for quite a while. His home could not have been more basic, barely accommodating his own lonesome life. This man had travelled around the world, but his humble home and living conditions reflected nothing about his experiences. There, sitting in that tiny space, he was describing the great endless seas and journeys he had been part of. He narrated adversities, facing death and escaping it – he had even survived a shipwreck, clinging on to a wooden log for two days in the sea!

Was there a common thread for you during these portrait sessions?

A whole new chapter of coastal life was opening up for me right there. He spoke of his fellow seafarers; many of them had passed on and the rest were struggling with a difficult old age. I was compelled to pursue the story and these lives, because theirs was an untold story. There were celebrated stories of travellers, traders and explorers who may have ridden the same ships as them, but the story of such common labourers and their hardships had never been documented or told. Even for me, it was a fortunate coincidence that had opened this avenue. From meeting this lone seafarer, I ended up tracing up to 35 of the surviving lot – each of them with unique stories, mostly of hardships.

How did you build and earn trust?

I spent a considerable amount of time interacting with them. In fact, a few years passed while I continuously met them and discussed their stories. This meant we had gotten accustomed to each other with a cordial rapport over time. The portraits were in fact taken during those conversations, as and when I felt the time was right. So it was all an organic process…mostly with a human-to-human basis, rather than a photographer-to-subject one.

What compels you to share their stories?

I felt compelled to bring their stories to light mostly because they were untold. Like I mentioned, stories of sailors and traders were celebrated worldwide. Even a single journey to a far off land was sometimes lauded as discoveries and achievements. But the labourers spent a lifetime making the same journeys and enduring a much higher degree of hardships. But being labourers or common men, their lives were neither pursued by historians or researchers, nor did they have the voice and ability to speak out their parts. This was typical of the working class in any part of the world, in any industry. I happened to come across their lives by chance, but I always felt advocative about the stories of such subjugated, marginalized lives in society. The coastal life as a whole had this general trait, which is the reason I was always inclined to retell their stories.

How have you been creatively engaged during these unruly and isolated times of the pandemic?

The lockdown came with a lot of travel restrictions. But I have been able to visit the coastal strips and photograph the effects of monsoon there. The time has helped me develop the ‘Home’ series.

2 Comments

wonderful photos and a wonderful write-up..!! from the heart..!! 🌹🙏

It’s really a human to human, heart to heart story of a true artist..🥰

Comments are closed for this article!