Seth Adams

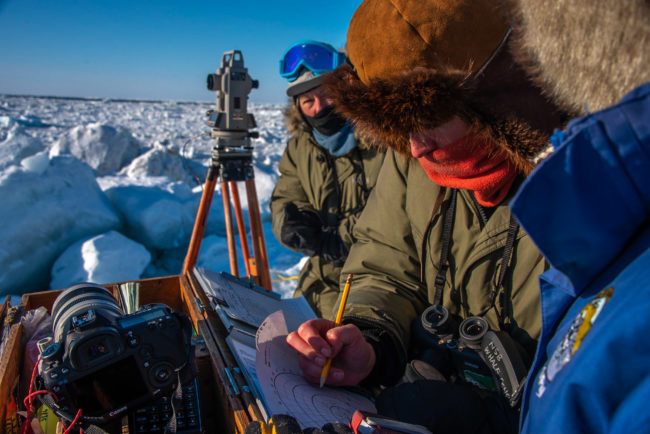

It’s a once-a-decade survey of the bowhead whale population in the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas. As the bowheads migrate from the Chukchi Sea to Beaufort Sea they swim past Point Barrow. The researchers set up the perch on a pressure ridge overlooking an open lead where they visually count the whales as they swim past during their migration. It’s a fascinating project that is very little known.

Was this a personal project?

Yes, sort of. I was in Utqiaġvik (formerly known as Barrow), which is the northernmost point in Alaska, with a program called Skiku that sends volunteer coaches to rural Alaska to teach kids to ski. My wife, Faustine, used to live in Utqiaġvik so for her it was a trip back to her old stomping grounds, and hearing stories about the place, the sea ice, its people for years really made me want to explore this part of Alaska I did not know. Geoff Carroll is now retired, but worked for decades as a biologist with the North Slope Borough’s Wildlife Department and as a Wildlife Biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. He is also an old friend of Faustine’s. He was going to head out onto the ice one afternoon to take on a shift with the Bowhead census, and he invited us to come along.

What is “the perch?”

The “perch” is a high point on the sea ice pressure ridge that the Census team builds up and where they set their workstation and a blind to do their observations. The blind is mostly there to shield people from the wind and make it a little more comfortable to stand on the ice for hours. The team also sets up a comfortable wall tent close by the perch to rest, make food and warm up. The tent is surrounded by an electrified bear fence to keep curious polar bears out of it. The first day we went out we had been skiing with the middle school kids all morning, and Geoff invited us to go out with him that afternoon. We were able to borrow a snowmachine (that’s what we call snowmobiles in Alaska), so we headed out! Geoff didn’t really know I was a photographer, and that’s not why I was going. I just took my camera stuff because I always do. We went out twice more, as well, and on two of the days (but especially the first day) I got super lucky with nice light.

How did you get access?

“Access” was a little funny, because on the North Slope taking pictures of anything to do with whales and especially whaling is pretty sensitive (and rightfully so; whaling can be controversial, and people don’t want to see their culture and traditions misunderstood or criticized by people who don’t understand the history or context.) However, I didn’t fully realize how controversial photography out on the sea ice can be at the time, and it was only a little later that it was explained to me just how sensitive it all is. I’ve since asked if it’s okay to use these photos to tell this story, and since my photos are really of the census and not of whaling I got a general okay to tell this story. Legally, of course, you don’t need it, but it’s a matter of respect.

Why is photography so sensitive?

I feel like I understand, but now that I’m asked to explain it, I’m not sure how to. There is a lot of history on the Slope, and because it’s such a small community things that might not seem like such a big deal to outsiders don’t get forgotten in the same way. I can point to one thing, for sure, which was a teenage kid from Gambell (an Inupiat village on an island off the western tip of Alaska) who harpooned a big whale. It’s a big deal in Inupiaq culture, and a big deal for the village – a whale will feed the whole village for an entire winter. Some photos were posted on Facebook by relatives, and were picked up by a newspaper reporter in Anchorage, where the catch was covered in a positive way. But then some asshole from an animal rights group launched a coordinated internet smear campaign against the kid, and he got non-stop hate mail and death threats and the like. It was really mean, and no matter what your views on whaling it was a fucked-up thing to do to a kid. That event is something that many native people cite as a reason that publicizing the traditional whale hunts only has downsides for them. Here is a story about that whole event.

And actually, I read that article over a year ago, and just now I quickly reread it as I pasted the link, and I noticed something that makes for a good example of why it’s hard to tell stories about the North Slope – the article says that Gambell is a Siberian Yupik village, whereas I just wrote that it was Inupiat. From my perspective, it’s easy to say “I’m pretty sure they’re Inupiat. Yeah, I think that’s right.” and write it down. But when you’re a white guy who parachutes in, but then gets something like that wrong, it’s a huge deal to the people whose lives and cultures you’re writing about. It’s all very personal.

How many days did you work on this, what was your biggest obstacle?

I shot all these photos in three short afternoons. The biggest obstacle was access to the sea ice – we had to borrow a snowmachine to get out there, and one wasn’t always available. One of those same days I heard that one of the crews had gotten a whale in the late afternoon – and the evening light in town was unbelievable (by mid-April it’s nearly light all night that far north, so “evening light” can mean 10 or 11pm) – and I was dying to get back out on the ice to see it and take pictures, but everyone that had a snowmachine was out riding it! So no dice. That’s why there are no pictures of actually landing the whale. I was pretty bummed about that at the time. I wanted to experience the happiness and community getting together to help with the whale.

How did you travel, and what were you trying to protect yourselves from?

We flew to Utqiaġvik, and got around town by car. But travel onto the sea ice was by snowmobile. The whaling crews very (very) laboriously chop a trail through the jumbled sea ice in anticipation of whaling season. Guns are for protection against polar bears, which can be a real danger out on the sea ice.

How did you protect yourself/gear in these temps?

The gear does fine in the cold, though obviously battery life is shorter. You have to be careful when you bring it back inside to protect it from the warm air, as condensation can form in places where you’d really rather it didn’t. There are a few tricks to keeping gear working in the cold, but mostly it’s fine. Keeping ourselves warm was a whole other deal, though – we had warm enough clothes to “actively stand around” while we taught kids to ski in the warm April sun, but we didn’t know we would be going out onto the sea ice when we packed for the trip. Out on the sea ice it is fucking cold. The wind blows in literally off the North Pole and it’s fucking cold. I was able to borrow a big sheepskin coat from Geoff – the same style the locals wear- after the first or second day out in the cold, and after that I was warm enough. But before that I just suffered.

Tell us about the drone shot.

I love drones for the ability to set the scene. I feel like the scale of and ‘out-there’ness of the place is hard to capture from the ground. I included the video and the photo that looks out across the open lead for that reason; the one with the cluster of snowmobiles in upper left of the frame shows the spot that the whaling crews launch their boats from, and where a whale was hauled out the previous day. The Perch is on the right side of the frame in the same photo; it makes for an interesting metaphor, because it shows that the census and the whalers are separate, but also how inevitably close they need to be – they both need to share the trail onto the ice, share the open open lead, and they rely on each other in the event of any emergencies.