Quick question.

What’s the fastest way to make someone cry?

Easy answer: encourage them to think about their loved-ones dying.

Either in the present, (which is super-sad,) or deep into the indeterminate future, once they’ve grown old.

Imagine saying goodbye to your life-partner, in your 80’s, after decades together, and then living your final days alone?

Guaranteed waterworks.

Do you doubt me?

Consider the opening 2 minutes of “UP.”

How quickly did you cry?

Or what about that massive Google commercial during last weekend’s Super Bowl? My son and I were mostly skipping the ads on the DVR, briefly stopping at the ones that seemed intriguing, or were worth mocking.

(His criteria.)

We saw the Google ad in question featured an old man, interacting with an AI, which through smart-learning could begin to categorize his memories, via his digital footprint.

(Rough synopsis.)

He recalled his dead wife, in a tragic, breaking voice, and then they showed old photographs of their life together.

Good thing we were skipping quickly, or I would have cried for sure. Theo was of the opinion the ad was emotionally manipulative, and I had to agree with him.

Very often, memories need triggers, in order to dislodge from wherever it is in our deep-brains they reside, so they can flash back to the front of our consciousness. (Like going from the hard drive to RAM.)

We all know that smell can trigger us, or sound.

Who hasn’t gone back in time when they hear a certain song?

(Seriously, if you play “Don’t You Want Me,” by the Human League, I will regress to a 7 year old.)

And, of course, we have photographs.

If ever a process were invented to aid memory, it was the one cooked up by the collective geniuses who figured out how to chemically capture light. (Or is it genii?)

Those brilliant 19th Century bastards who gave us the medium we now treasure.

And what a time it is to be a photographer.

Sure, photography was adopted by the masses each time technology allowed it, but the IPhone/smartphone revolution has taken things to new levels.

So much so that the concept of photography as separate and apart from other things is beginning to seem quaint.

So much so that venerable photo institution PDN closed last week, and the Washington Post folded its photography newsletter, almost simultaneously.

The nature of photography has changed, and it’s now a living thing, a visual language, and even temporary, as much as it’s supposed to be a physical, permanent record of what really was.

(Frozen light particles that bounced off of real things in the real world.)

Now, we photograph our parking space at the airport, or the information on a flyer we want to remember for a day, or a selfie because the light was good, but we’re never going to look at it again.

Digital photos, the lingua franca of our time, are not designed to be archived forever, like a contact sheet in 1983.

(Or 1883, for that matter.)

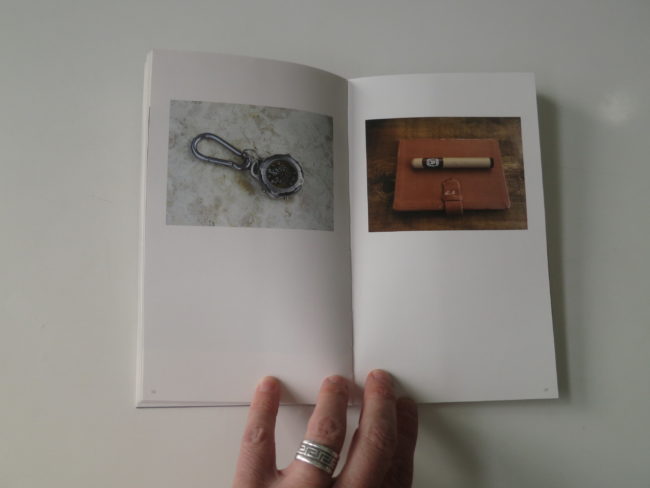

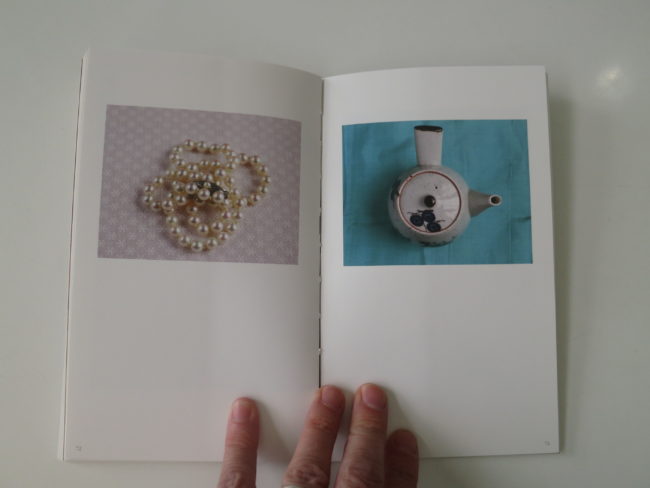

But objects, real physical things in the actual world, do retain resonance.

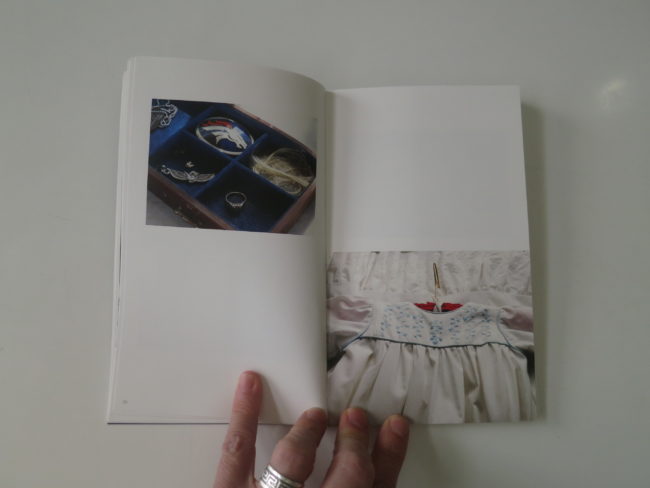

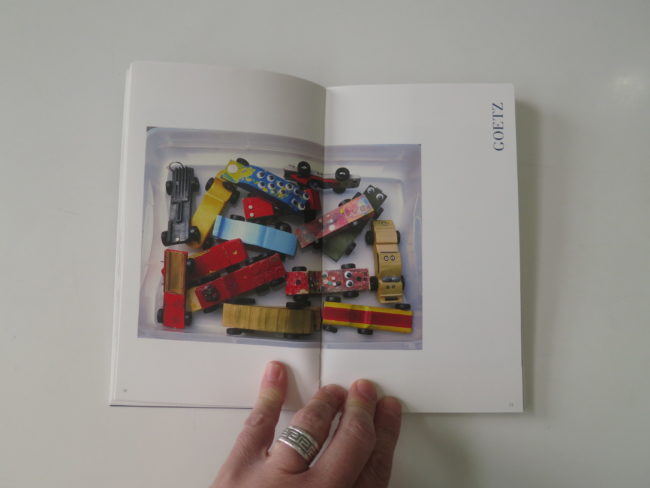

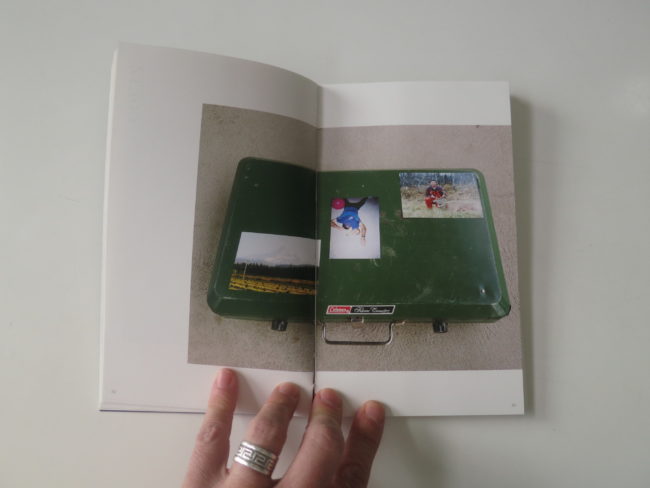

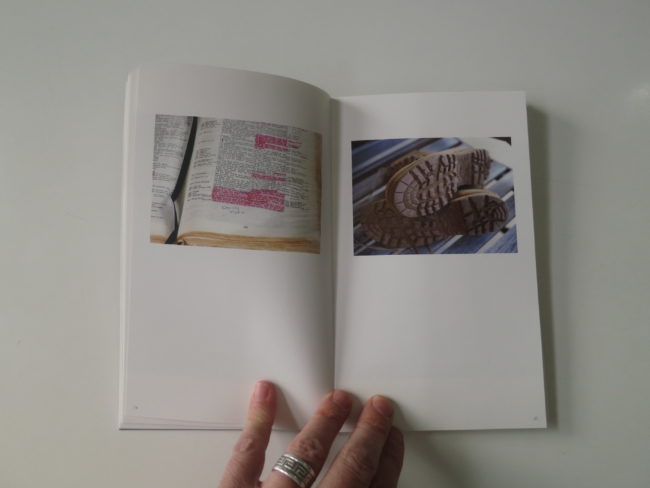

T-shirts can smell for a while, because of your cousin’s distinctive detergent. Boots and Barbies and Bibles can trigger memories too.

And of course books are also well-suited to capturing the spirt of the dead.

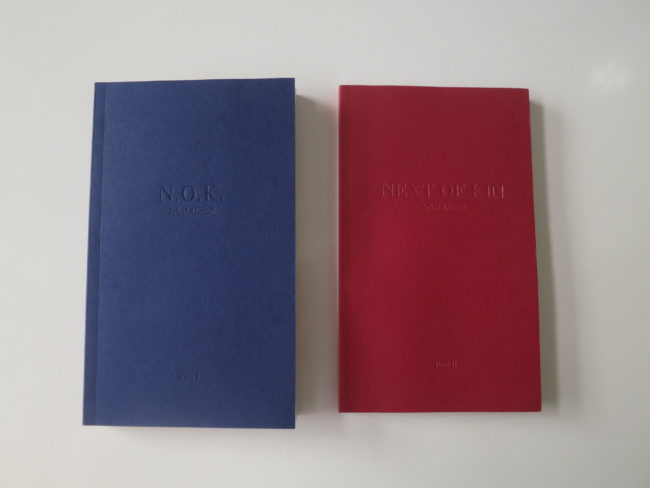

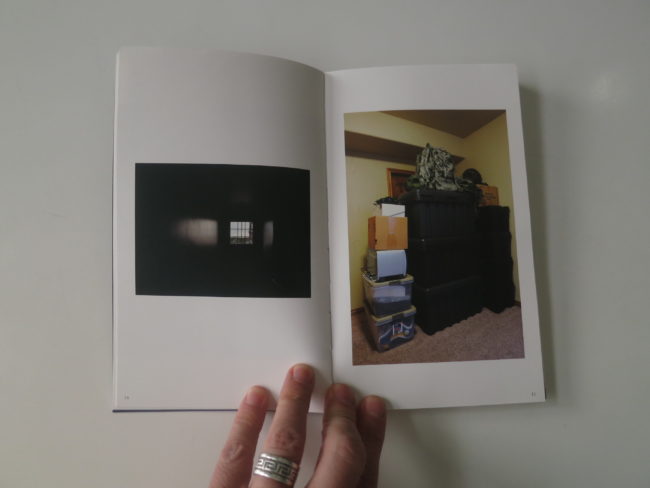

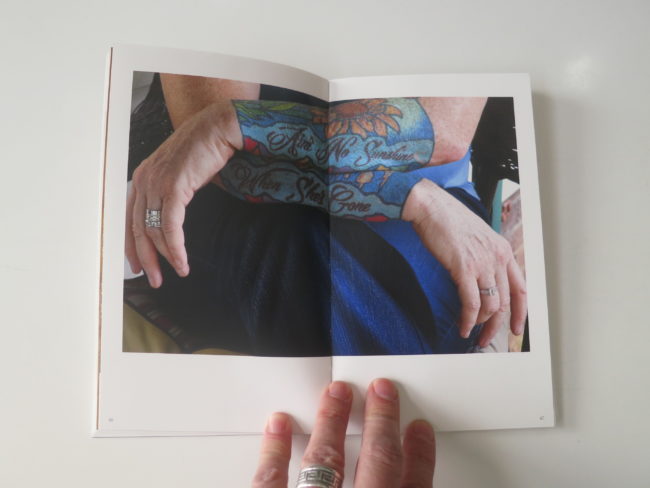

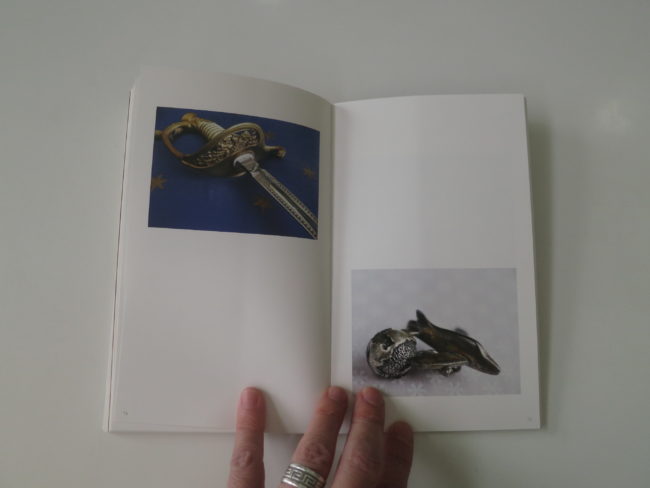

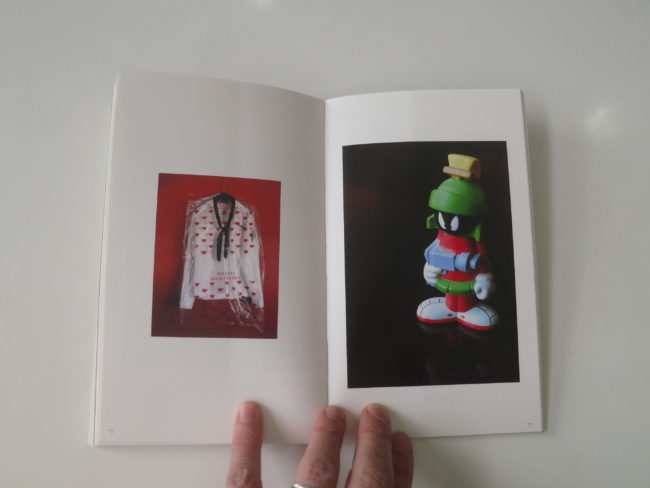

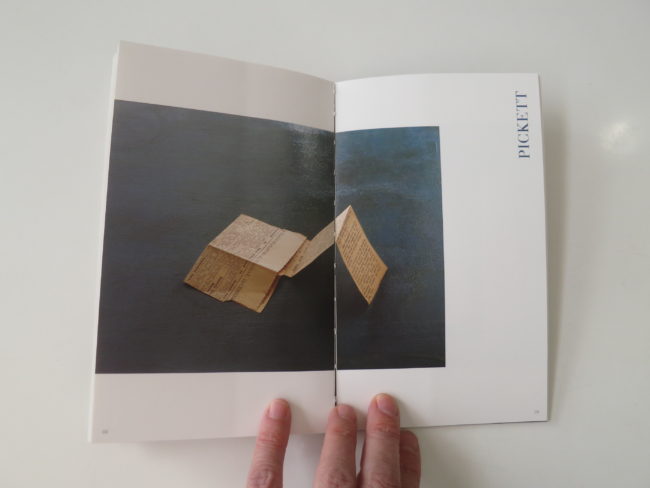

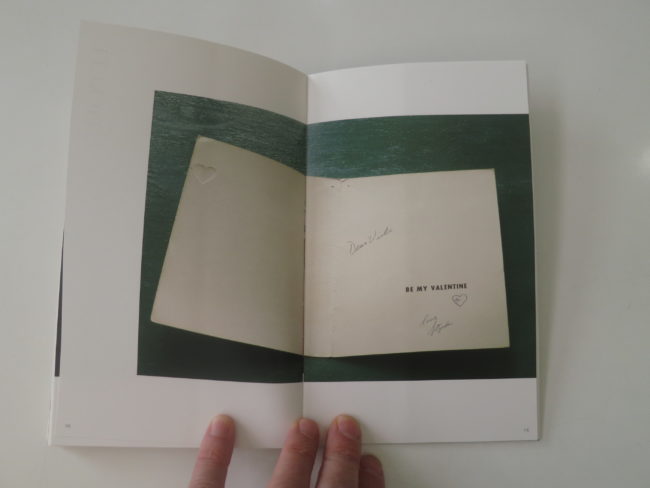

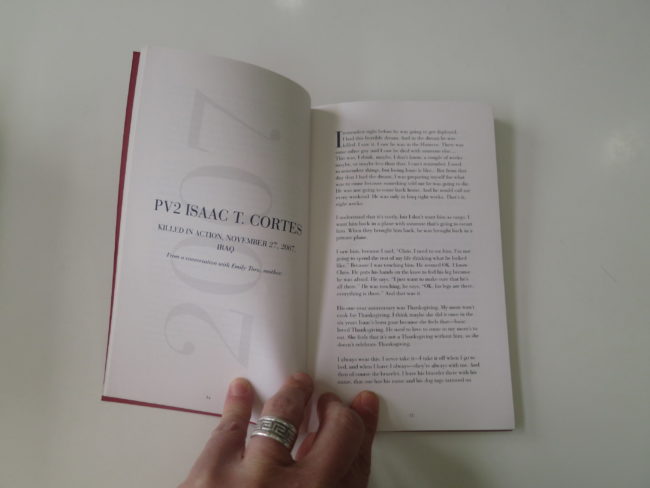

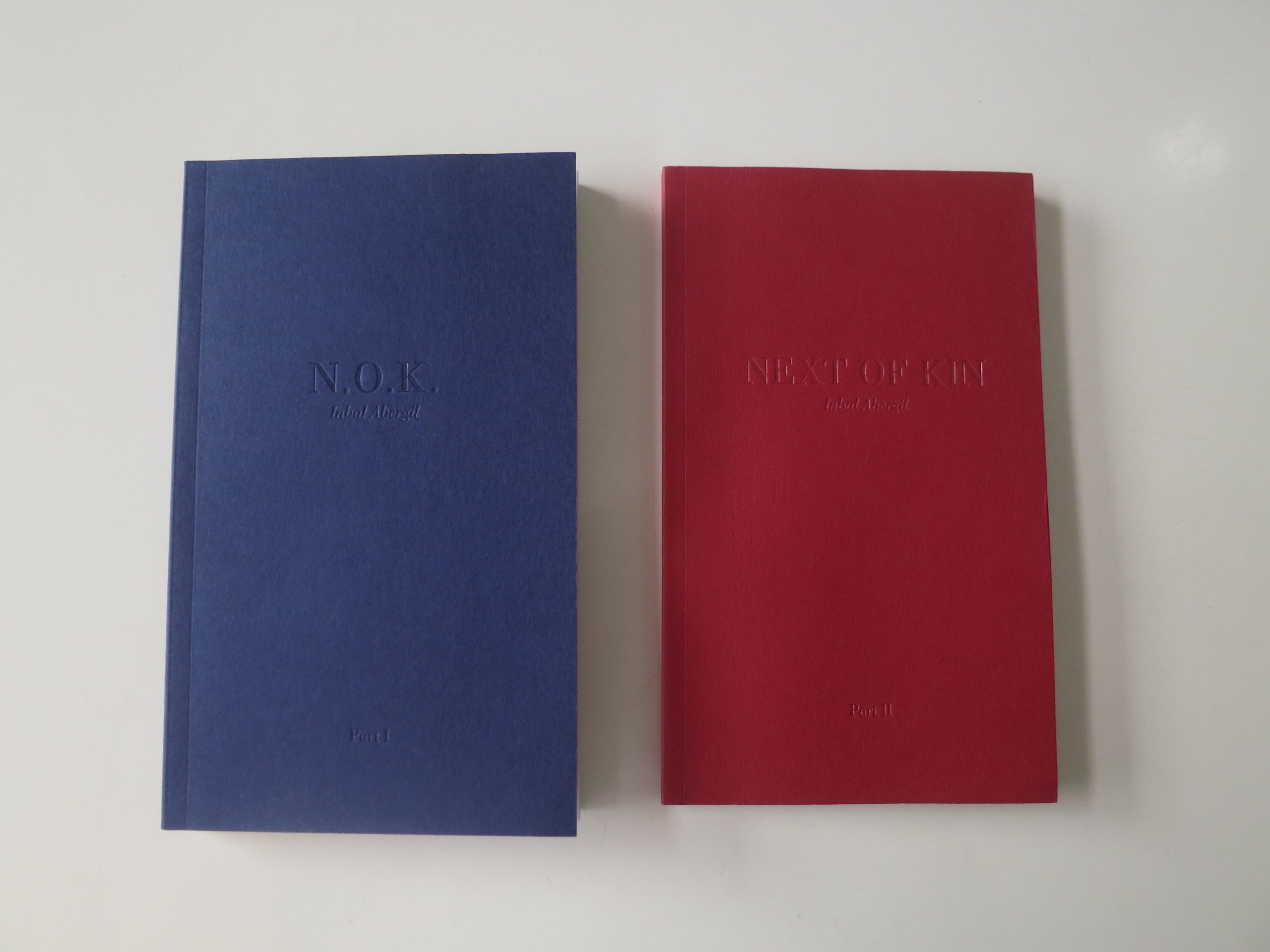

In this case, I’m thinking of “Next of Kin,” a recently published set of photobooks that turned up in the mail in late #2019, from Inbal Abergil, published by Daylight.

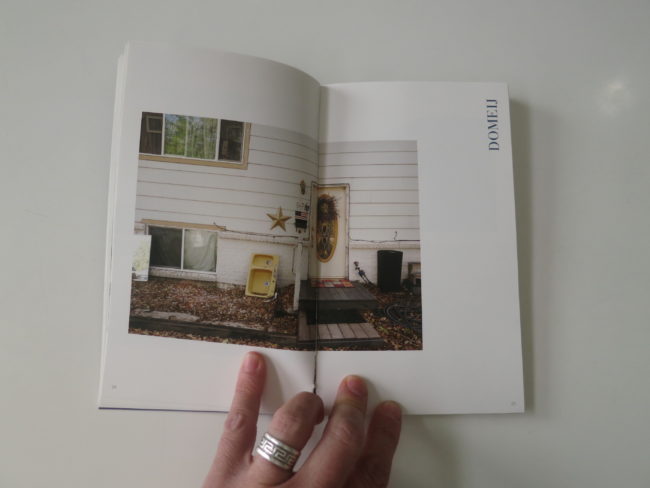

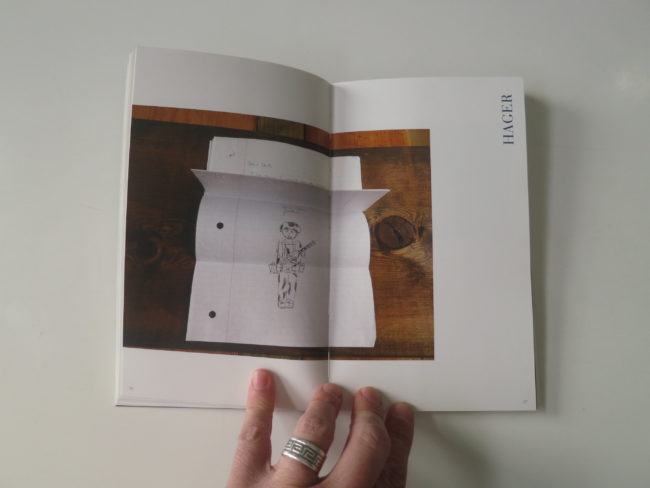

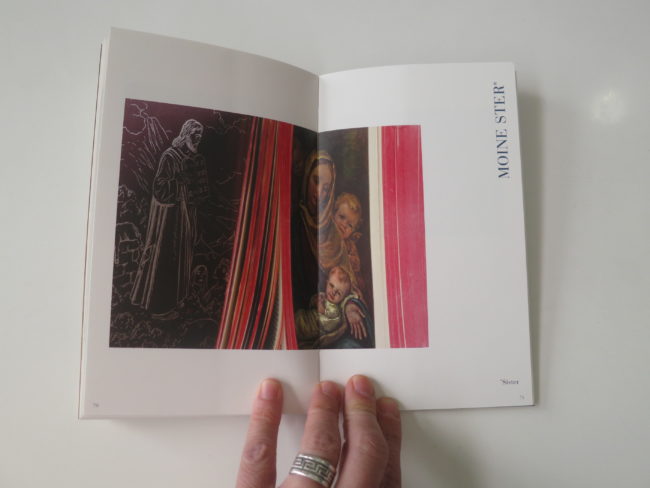

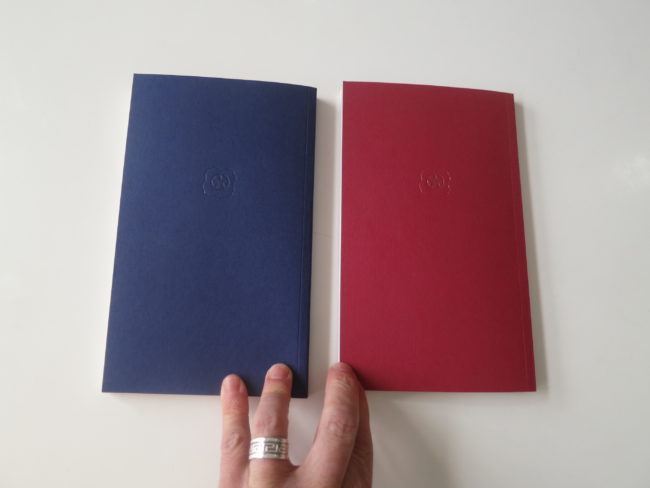

The covers, in blue and red, are marked Part I and Part II, and the first book has little text beyond a dedication and section breakers.

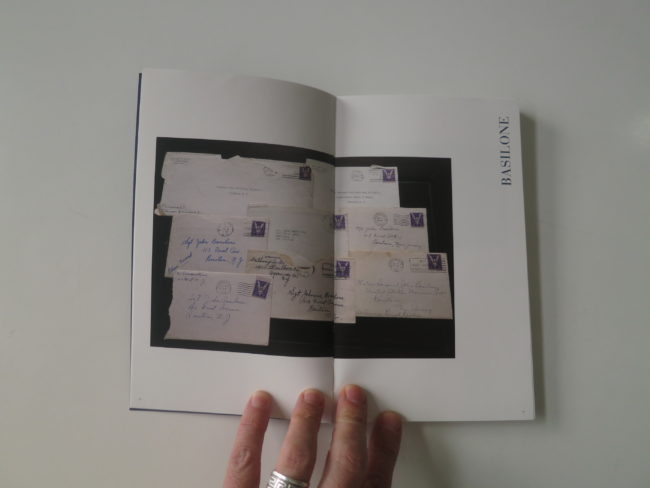

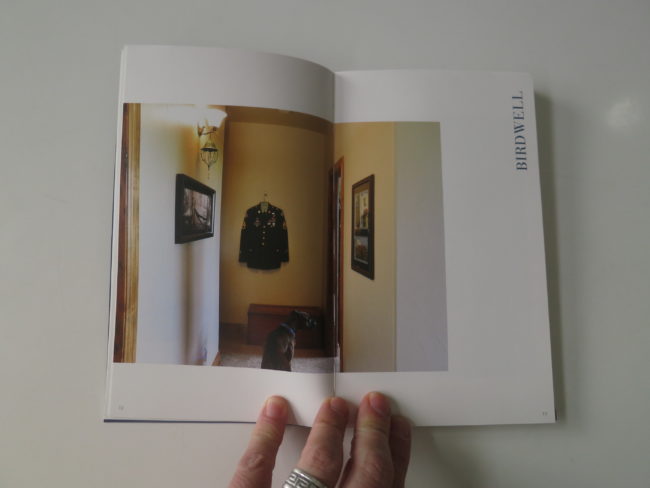

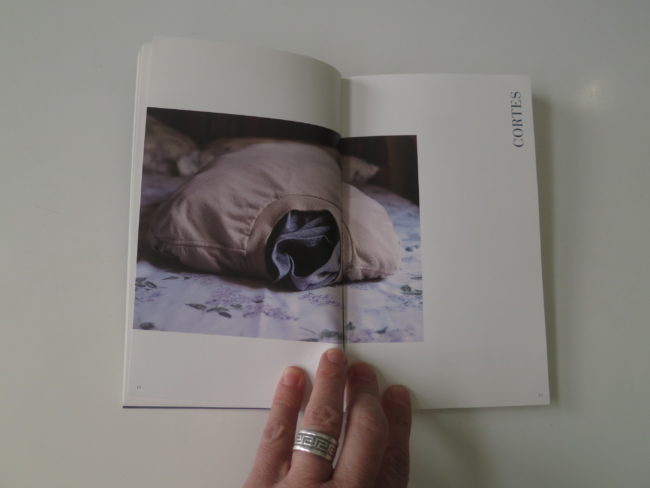

From the get-go, we see only one word, (a name,) printed sideways, but after one or two sections, you suspect you’re looking at the artifacts of dead soldiers.

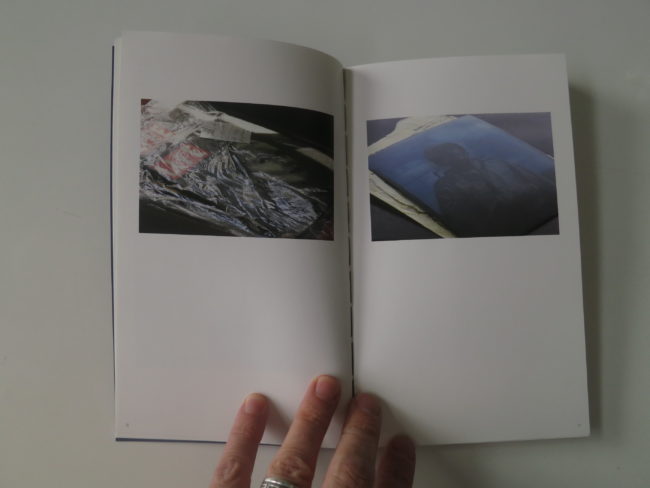

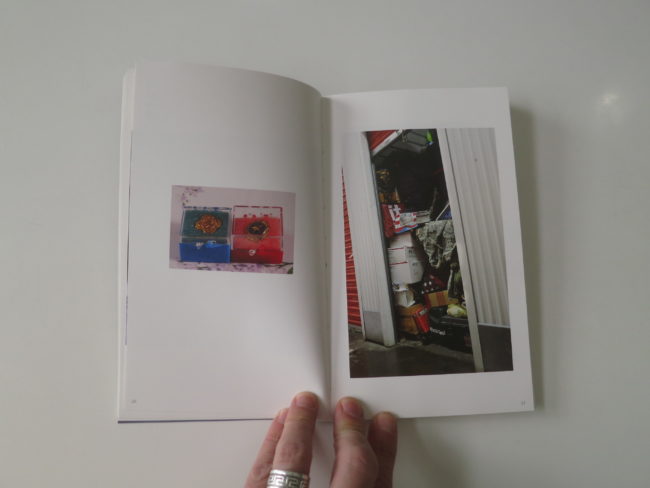

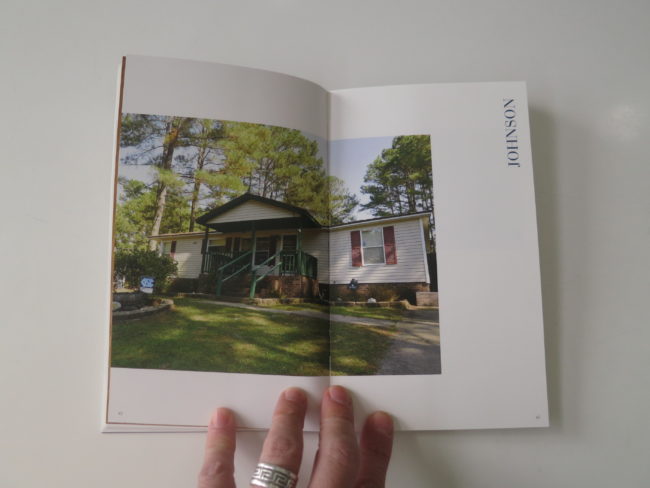

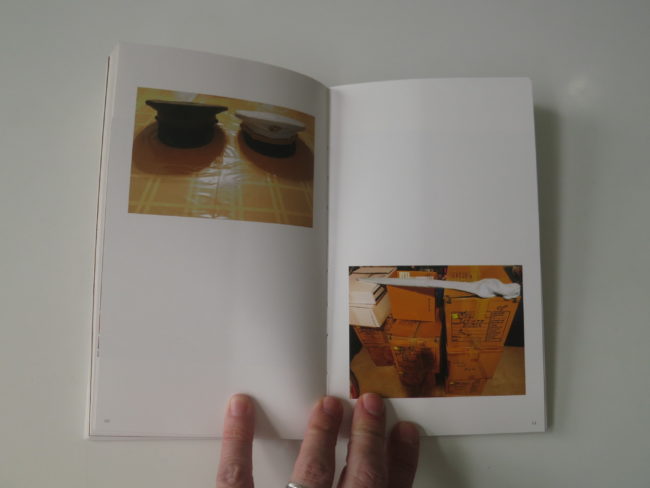

I wasn’t certain until the third section, when we see a full storage unit stuffed with life-remnants, but the second section features some heavy-duty storage objects, so the hints are there quickly.

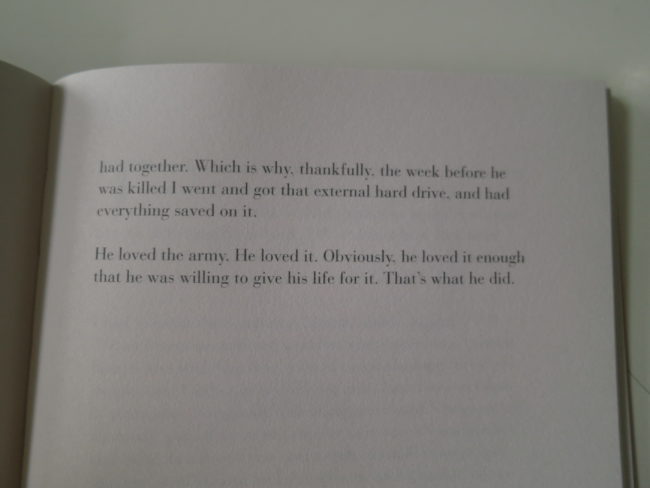

All the text beyond those soldier names is saved for Part II, which is a decision I understand. It says, this is not one object, but two, conjoined by the elastic band, and therefore, the viewing experience will be guided.

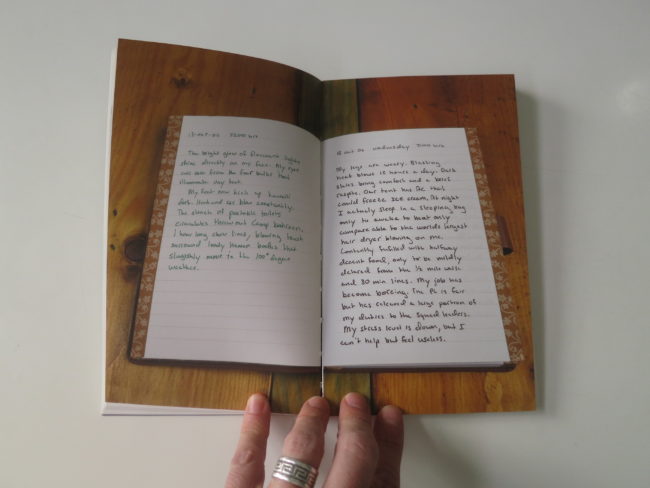

That is seemingly the main purpose of Part II, using words to house stories and memories from Gold Star families, the people who suffered the loss of a loved one.

To keep things intriguing, I think, the book opens with a historical death, from WWII, but of course most of the stories are modern, from Iraq or Afghanistan.

Most of the wounds are fresh.

The pictures are gracefully shot, and unlike that Super Bowl Commercial, are respectful with their handling of emotion. They’re sad, for sure, but not dripping.

(You can’t hear the strings in the score, if you know what I’m saying.)

Perhaps it’s a quibble, but I’d say that four commissioned essays, at the end of Part II, are a bit much. None are too long, and leading with the always-intelligent Fred Ritchin is a good idea, but given how many books I see, I think two contextual essays is plenty, maybe three if you’re being generous.

(Especially with all the other text.)

Early on, I asked myself why the artist was telling these stories, and if she mentioned her ethnicity when she originally reached out, I’d forgotten, as her name suggests she could be from many places.

Turns out, Inbal Abergil is Israeli, was a solder herself, and wanted to understand grief and loss in American culture.

This was a smart, elegiac, thoughtful way to explore the subject matter. And I hope all those families felt a measure of peace, after seeing their fallen warriors memorialized in such a classy way.

Bottom Line: Sad, graceful look at the aftermath of soldier’s deaths

To purchase “Next of Kin” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me directly at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are interested in presenting books from as wide a range of perspectives as possible.