Happy New Year, everybody!

Welcome to 2020.

(You’ll notice I’m not hashtagging it yet, as I did for the tumultuous, endless, and now departed #2019.)

It’s freezing outside, and my kids are still off from school, so I’m holed up in my bedroom with a fan on for white noise, and blankets huddled over my legs and feet, as the good heater is in the other room.

When I say freezing here, I don’t mean it simply as an adjective, in the descriptive sense.

I mean below 32 degrees F or 0 degrees C. (And as I’ve mentioned many times that I can’t do the conversion, we’ll stick to F for another year.)

Each year, in Deep Winter, it gets down to 0 F or below, with the wind chill.

When I woke up this morning, it was -5 F.

(And that level of cold will typically kill a person, so we don’t have a big homeless population here in Taos half the year.)

As I had last week off from the column, and finally got a chance to rest, I took advantage of a week of free HBO to catch up on “Succession,” which I’d heard was an important new show.

A friend who recommended it knows about the mega-rich, so I figured it would have authenticity. And the Uber-wealthy-megalomaniacal family it follows is clearly inspired by the Rupert Murdoch clan, with his conservative news empire.

The picture of sad, insecure narcissists, constantly fighting and betraying one another for proximity to wealth and power does feel relevant for our current era, which skews towards Oligarchy in much of the world. (All of the world?)

The acting is superb across the board, and I’ll bet that Jeremy Strong, who plays sad-boy son Kendall Roy, was using a fake American accent, so I’ll take a rare Google break.

Be right back.

Nope. He’s American, from Boston. (I guess that partially explains the nasally speech.)

Like most HBO shows I’ve seen since “The Sopranos” or “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” “Succession” is less proper art than intelligent, guilty pleasure, and the comps to Showtime’s “Billions” are rather obvious.

As the series writer, Jesse Armstrong, is English, and there are large set pieces in European castles and schlosses, there is a sense of insider-aristocrat-old-money-and-power vibe that adds to the glamour.

The differing, WASP, Massachusetts-liberal values of a rival media family, the Pierces, allow yet another window into the world of the .001%

And what of it?

What’s the takeaway?

Well, it echoes something a friend told me at a recent dinner party. He is super-successful, and mentioned that he’d recently heard about a study that super-rich and super-poor people were often equally unhappy.

He said he could believe it, from what he’d seen.

And we all know about the stereotypes of addiction, suicide and self-sabotage attributed to really rich kids as well.

Unhappy they may be, but EVERYTHING the Oligarchs experience in life is “better,” as depicted in “Succession.”

Better cars, (driven by others,) better food, (which is ever-present in every room,) prettier rooms, bigger spaces, private planes, visits to castles, private yachts, well-dressed servants, omnipresent helicopters, all of it.

What does it mean?

That the rulers of the world want as much physical space, and personal resources, as possible. They want transportation options that allow them to EXIST separately from the hoi polloi, and their money (almost) always protects them from accountability.

We see that people of unimaginable power, raised in the hothouse of extreme wealth, will often do and say anything to retain or increase that power and wealth.

Wait a second…

“Succession” is definitely about Donald Trump, in as much as it’s a metaphor for how that degree of wealth can warp a person, as we see with our President.

And in an age of extreme income inequality, maybe it’s important for history to have a document that shows this lifestyle for posterity? (Even if it’s fiction.)

There are many ways to present a narrative, though, and it’s equally important to understand the other side: the emergent street class in America.

In this column, we’ve discussed California shanty towns long before some in the mainstream media, and I’ve previously shown books by Anthony Hernandez, Joshua Dudley Greer, and Scot Sothern that depict elements of Post-Great-Recession American street living.

Last year, we also published Cecilia Borgenstam’s pictures of the artifacts of homeless life from Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

But in the photo world, (as I’ve also written,) the subject has been contentious recently, with some suggesting that no one should ever photograph the homeless, without themselves being homeless.

I can see how it’s an endpoint philosophically, and certainly with the help of non-profit organizations, some homeless people can undoubtedly take pictures, and be supported to have them printed or exhibited.

To show the world, from the inside.

But honestly, if you’re living on the street, survival is your primary concern, not documenting your condition for history.

And from my art training at Pratt, I’ve never believed in the insider-only rule. Outside of the vilest racism, or child pornography, I think that artists should be allowed to explore anything they want, and then have the resulting work judged on merit.

I think male novelists should be allowed to write deep female characters, and African-American film-makers can direct Asian-American actors.

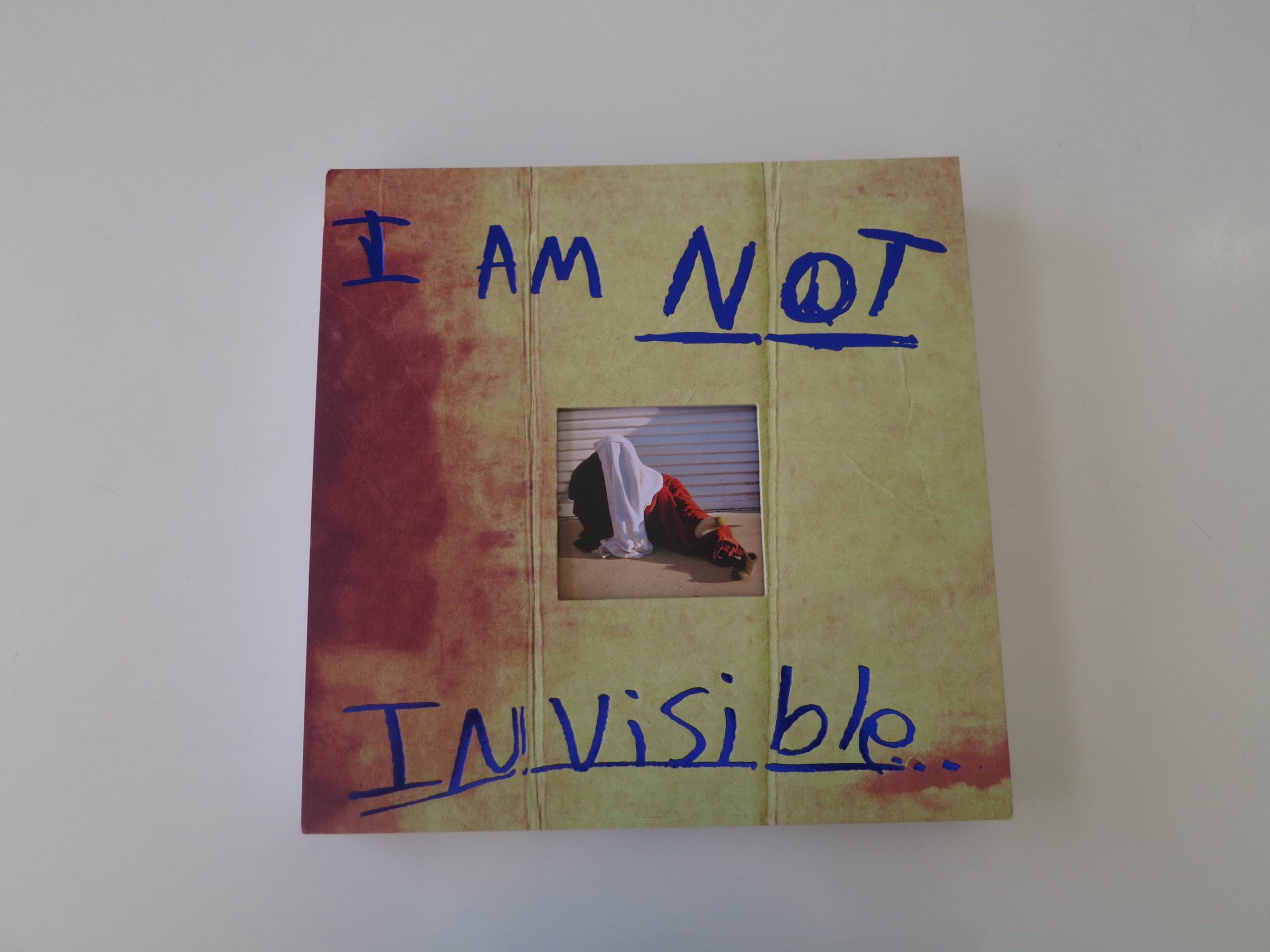

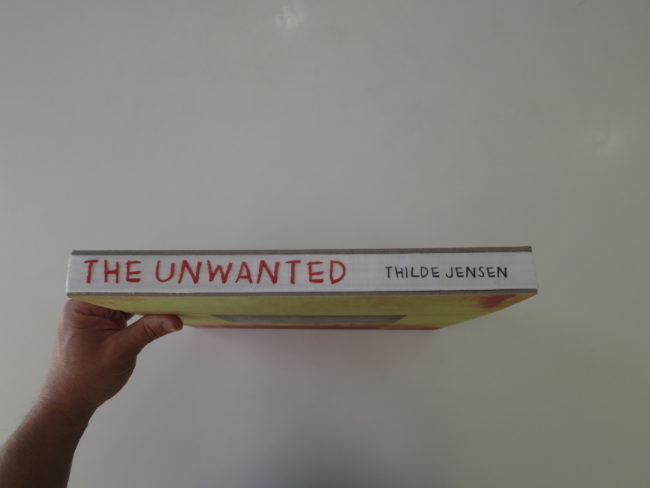

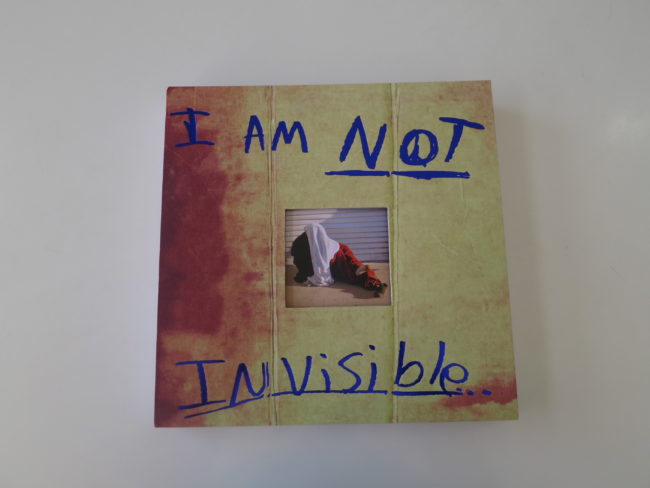

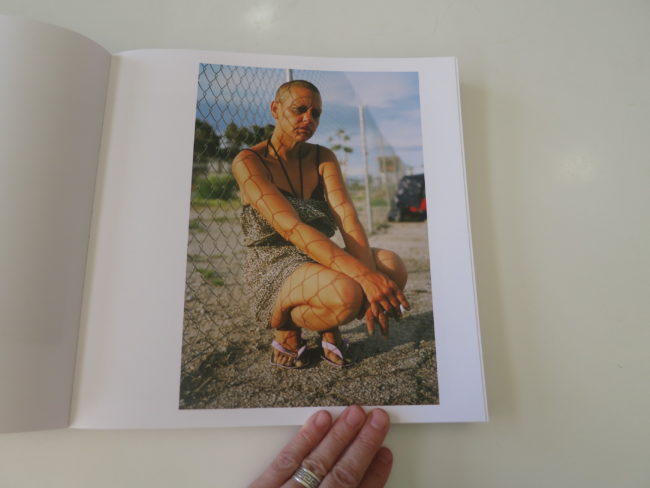

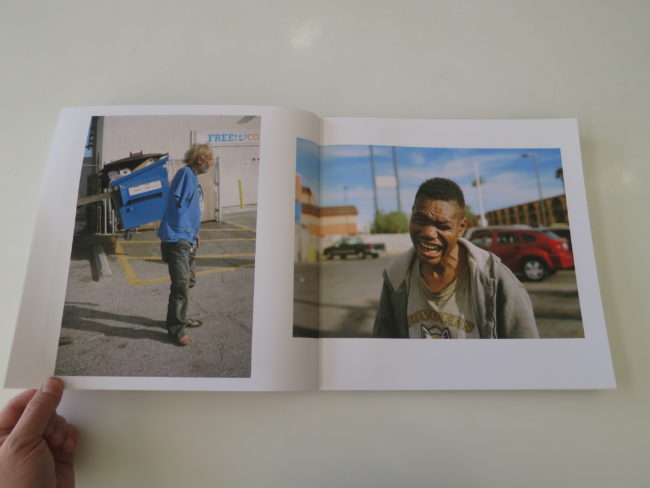

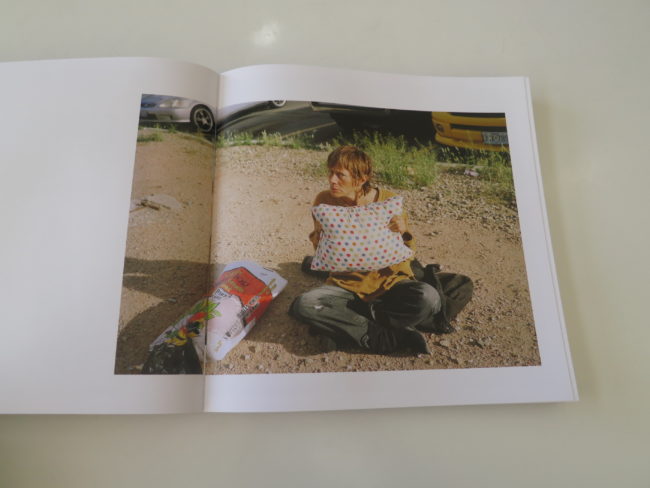

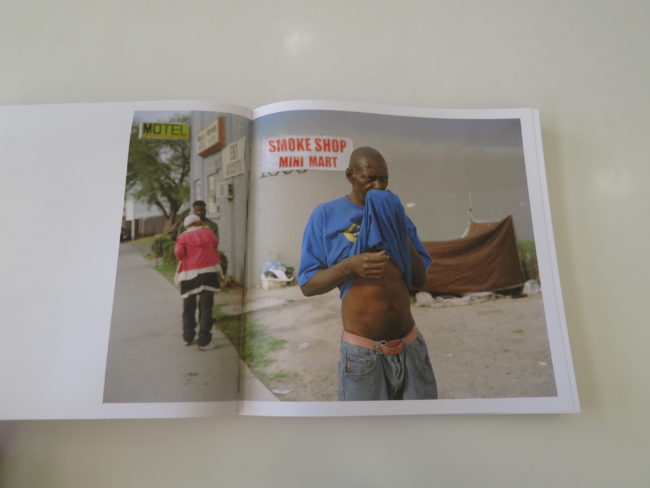

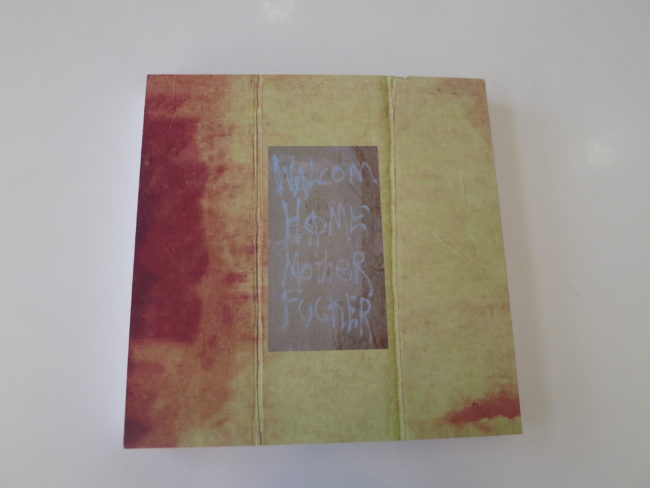

So after all that build-up, (a lot, I know,) for our first column of 2020, we’re going to look at “The Unwanted” an impressive book by Thilde Jensen, by LENA Publications, which turned up in the mail last year.

While I’ll admit that Ms. Jensen did give me a heads up about the subject matter when we corresponded, with my crazy #2019, I forgot what the book was about by the time I opened it.

So I was able to create an experience without preconceptions.

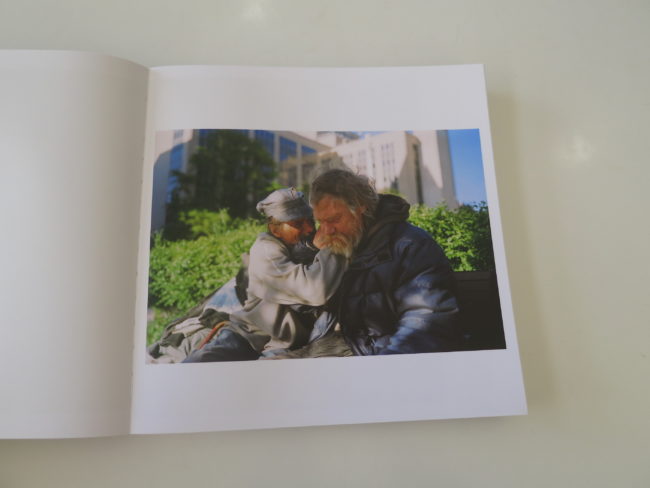

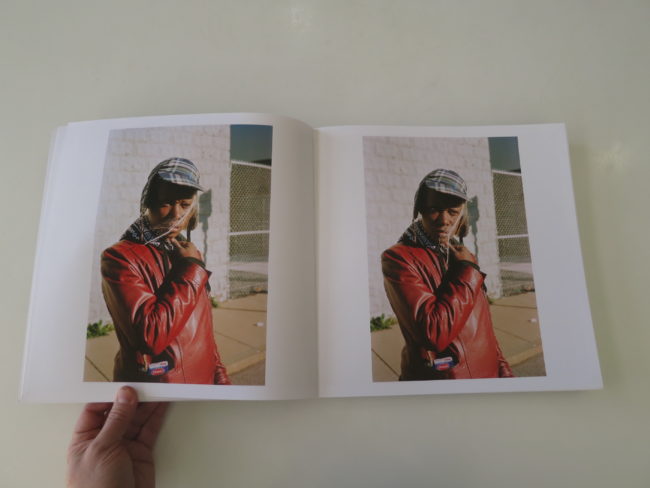

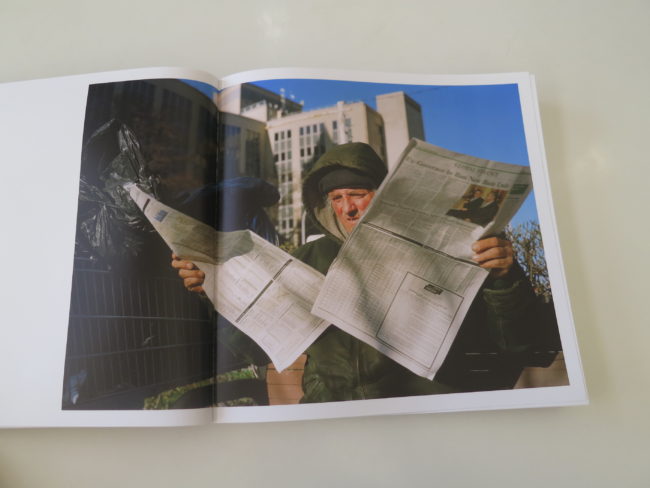

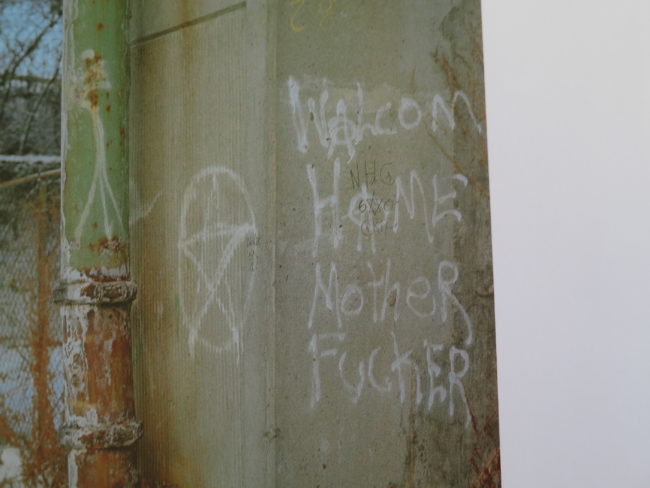

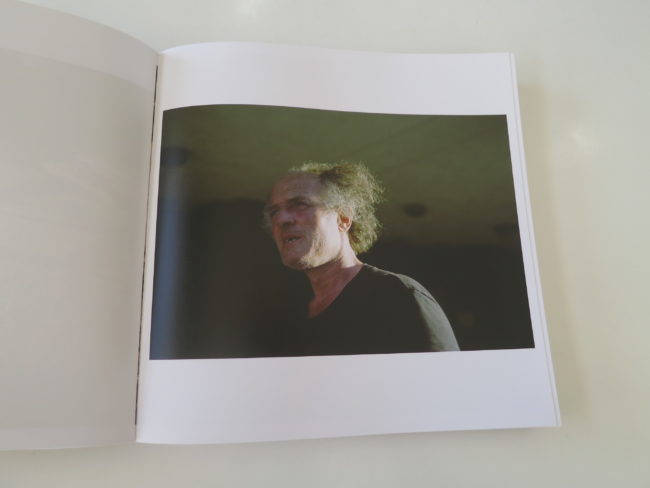

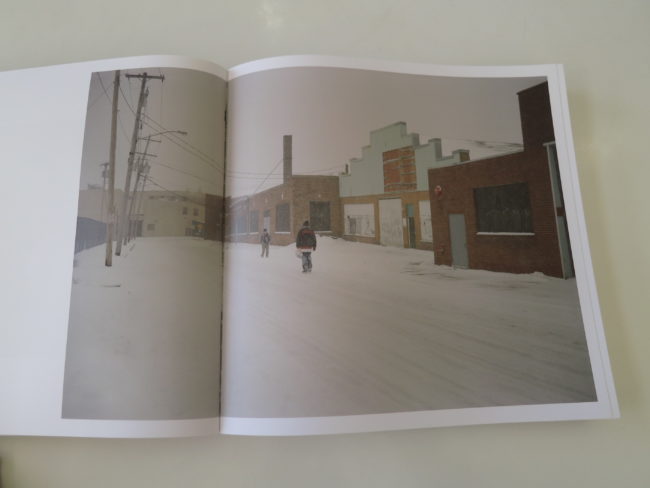

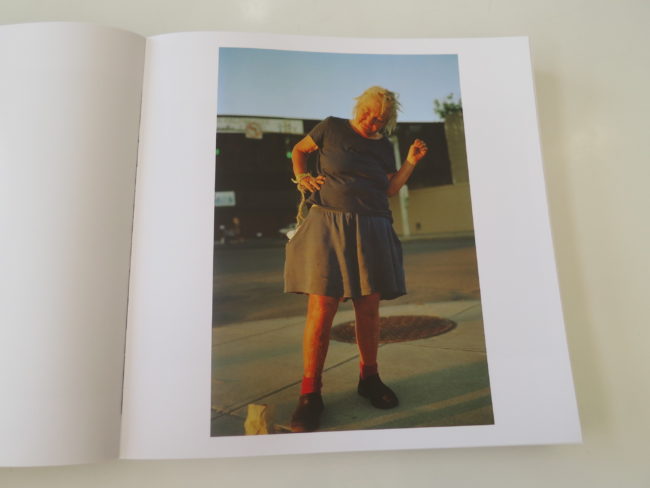

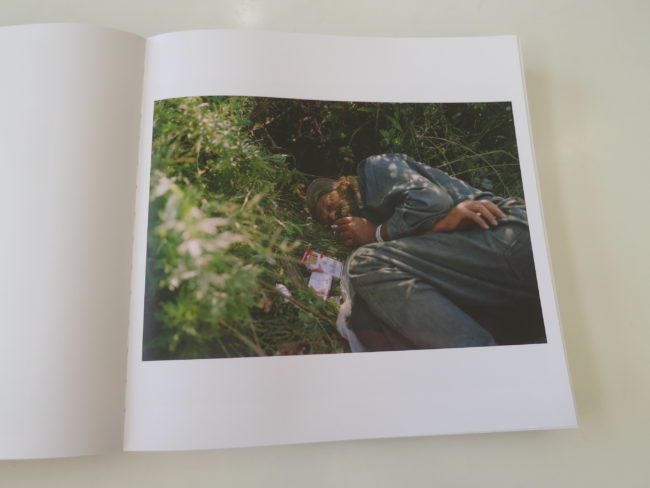

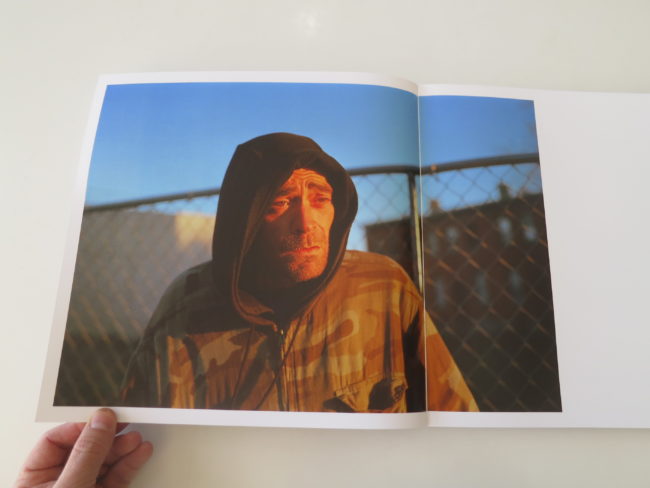

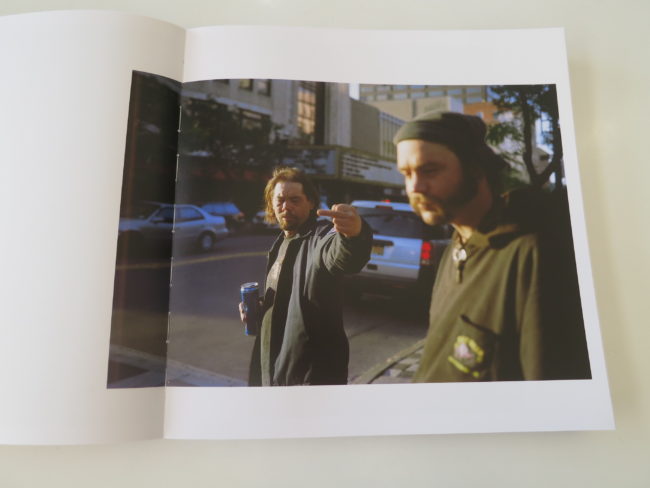

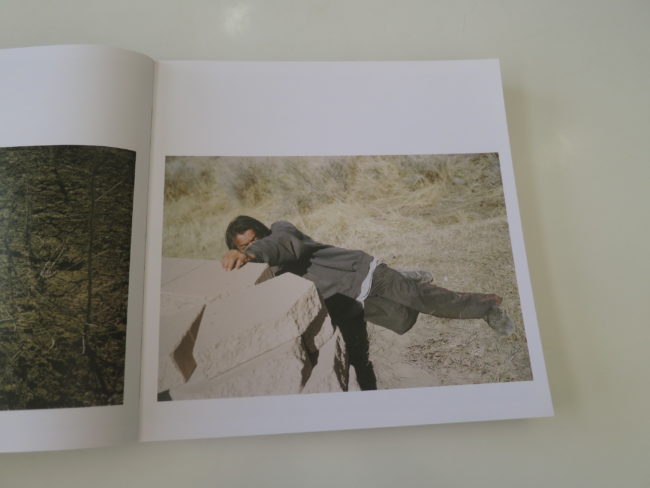

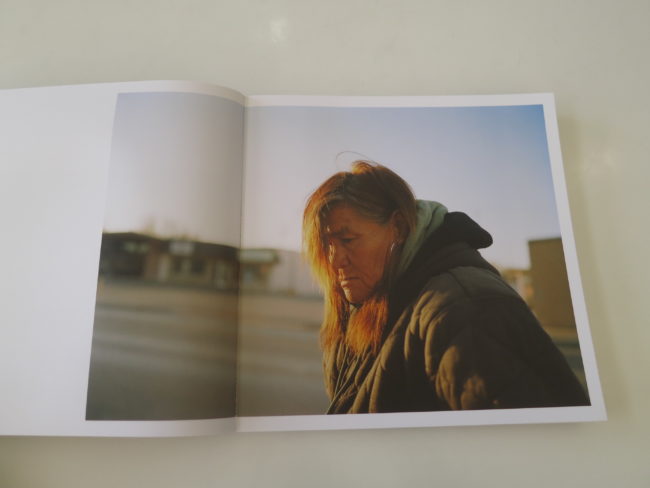

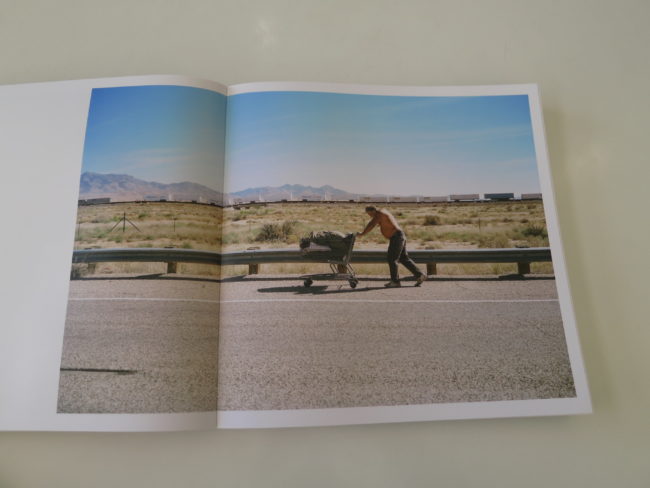

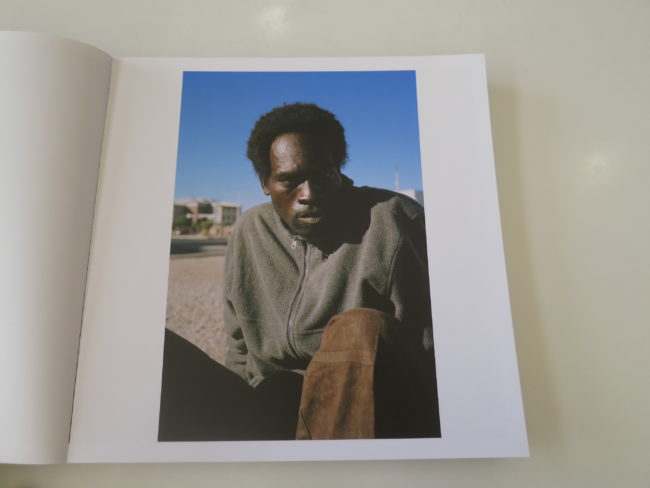

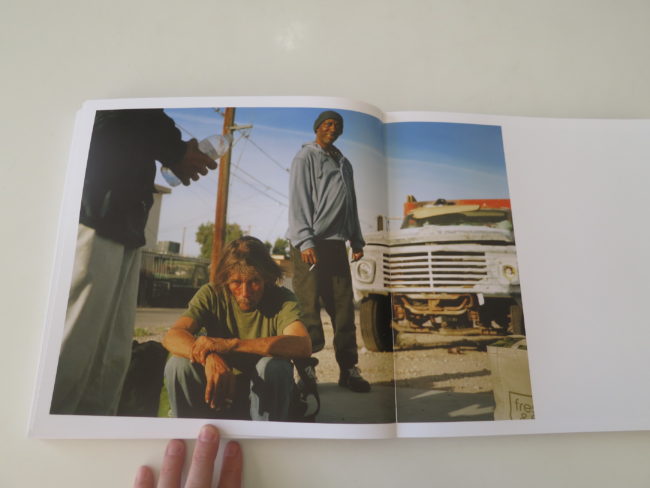

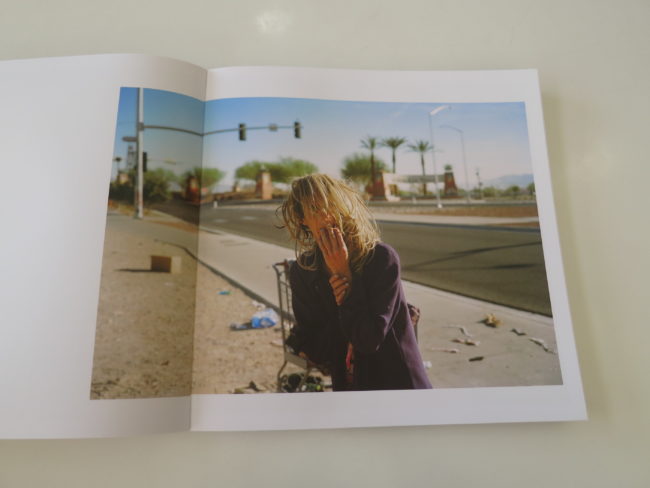

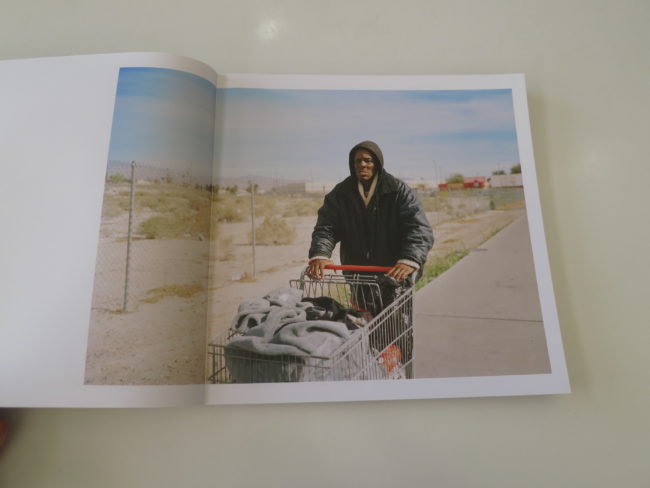

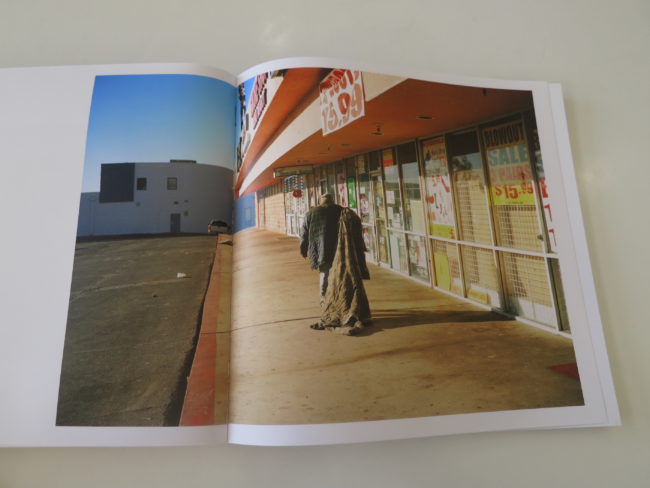

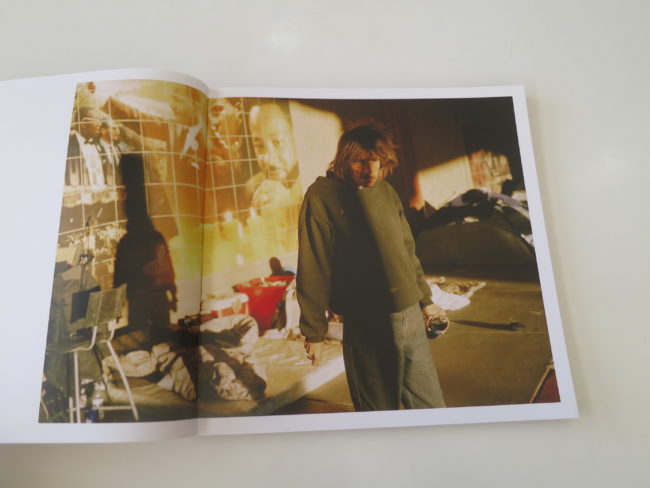

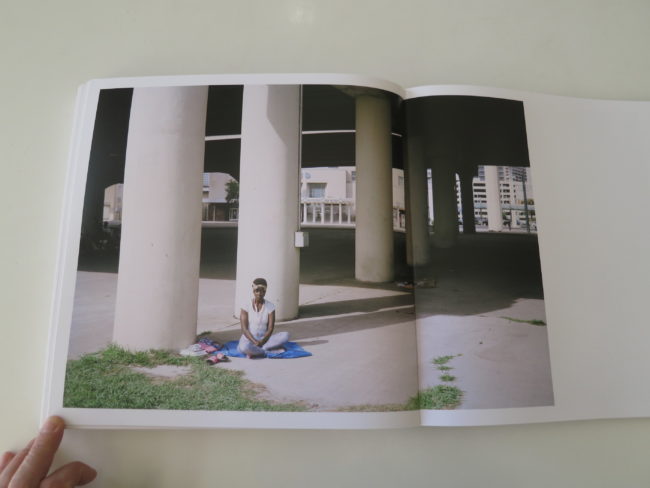

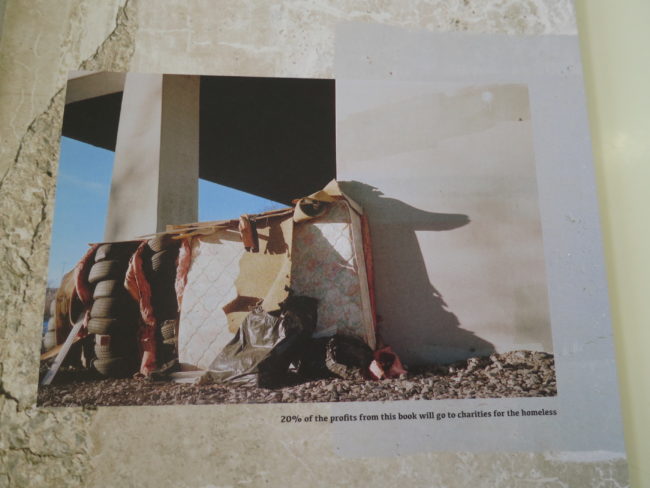

The thick cover, in yellow and purple, with a cut-out featuring a person sleeping in the street, with red pants, is jarring. As are the opening images of an underpass, and of a bearded white man sleeping on cardboard palettes, with his head propped against a brown, brick wall.

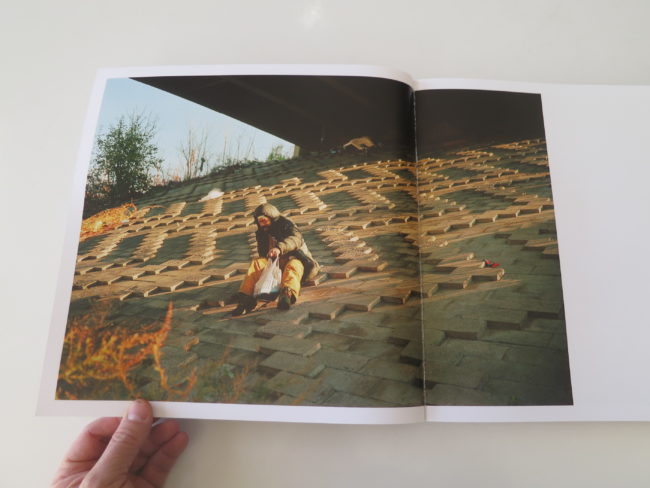

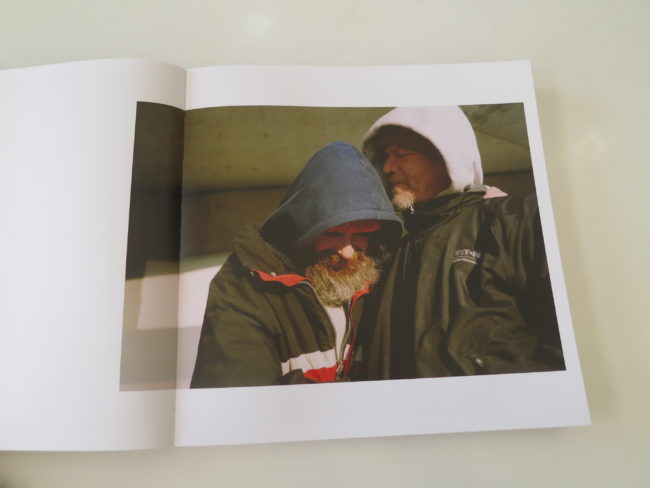

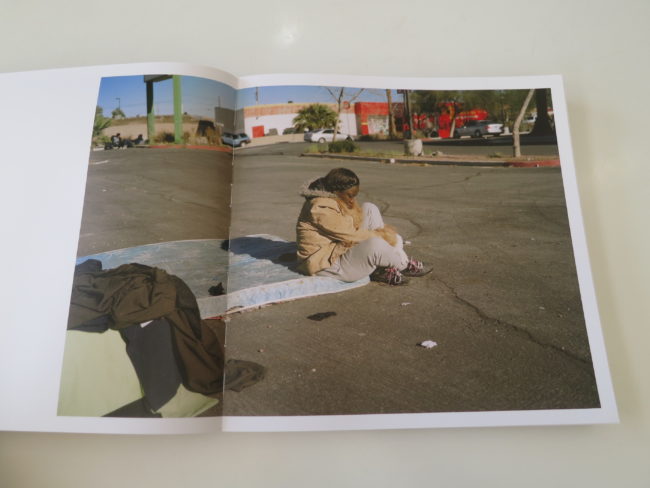

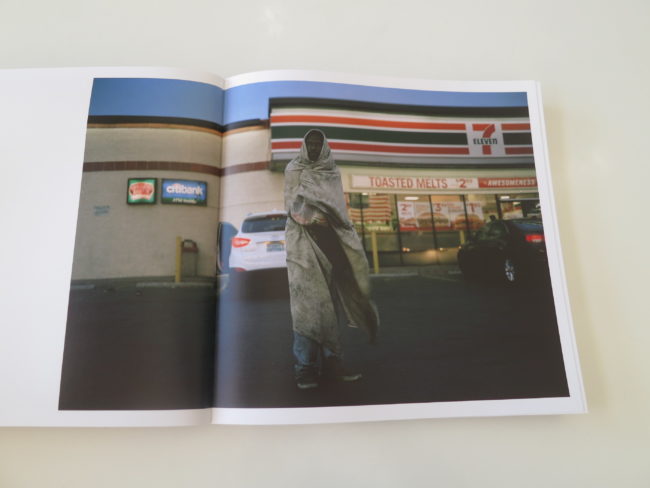

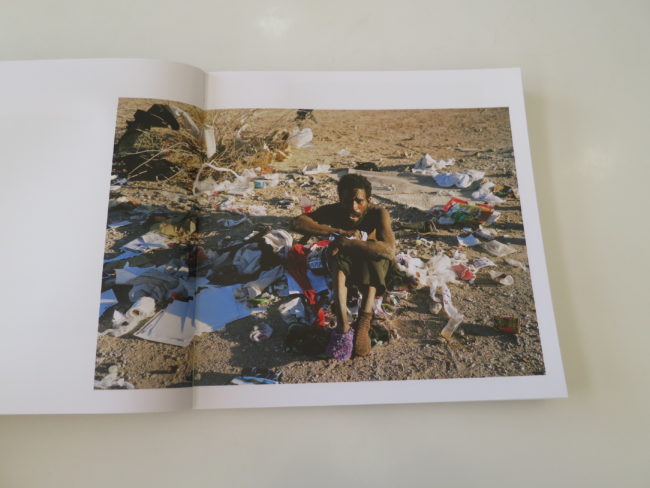

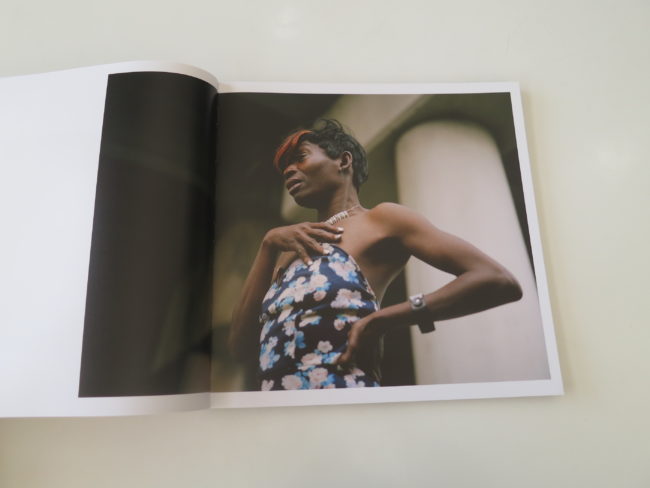

Truth moment: these pictures are bleak. And there are many, many of them.

In my mind, when I first connected the book’s size to its contents, I realized this was going to be a long, unpleasant ride, even if it was to be graceful.

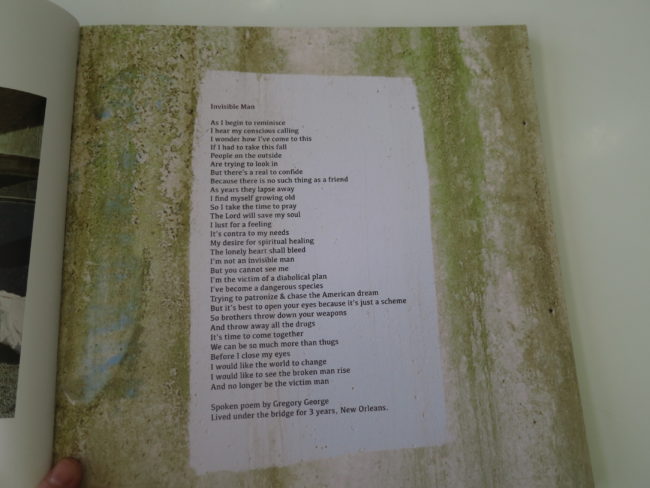

Given Ms. Jensen’s artistry, the work is compelling, and I did continue to turn the pages without skipping. I wanted to take my medicine, so to speak, as the book feels like it was meant for posterity.

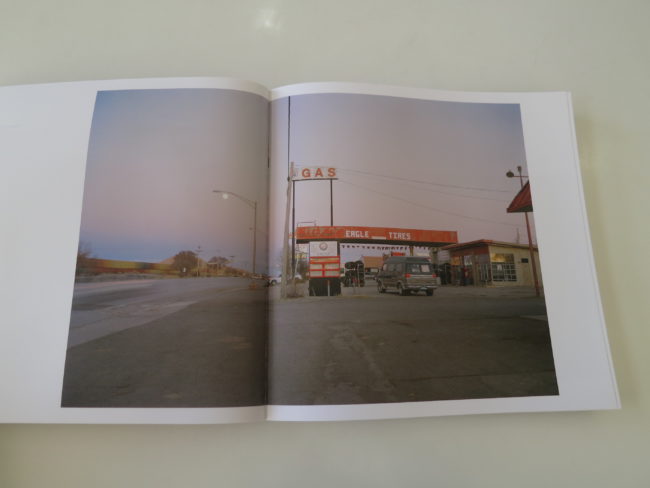

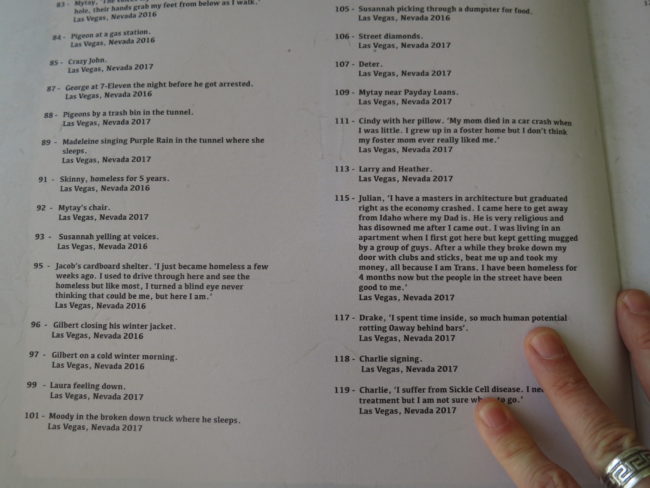

The locations change, though all relevant text is reserved for the end, so there’s some guessing at first. There was East Coast landscape, for sure, and I thought I recognized Las Vegas, and then New Mexico. (The end notes confirmed it was Gallup, which we saw last year in Cable Hoover’s project, “From Gallup.”)

There are pictures of so many broken people, living day to day. But unlike our fictional billionaires, these humans have as close to nothing as possible.

We’re not told where we are until the end, when the notes confirm NM and NV, and that the pictures were also made in Syracuse and New Orleans.

The notes also suggest that Ms Jensen received both Light Work and Guggenheim fellowships, which would mean this project has been blessed by the heights of the art world too.

In Gerry Badger’s essay, we learn that Thilde Jensen, (who herself writes of having suffered deeply,) was afflicted with an Environmental Illness, highly allergic, and was forced to live in a tent in the woods for two years, on a respirator.

She photographed that culture as an insider in a previous project, and brought that capacity for empathy to her coverage of America’s homeless, who often suffer from mental illness and/or addiction.

We also read, at the close, that 20% of the book’s profits will be given to charity.

As I once reported here long ago, the Library of Congress collects photography around themes. If I were in charge there, (which I’m not,) I’d be acquiring this project, along with some of the others I mentioned earlier, because I think this period in American history will need to be faced, down the line.

The last time income inequality was this bad, it led to the Progressive era, and the breakup of big monopolies. President Teddy Roosevelt, (admittedly Upper Class and racist,) became the trust-buster extraordinaire.

This time around, we’ve got Trump.

So who the hell knows what’s going to happen?

Bottom Line: Powerful, scathing look at homelessness in America

To purchase “The Unwanted,” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me directly at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are interested in presenting books from as wide a range of perspectives as possible.

2 Comments

Thilde Jensen’s photographs are moving, important and… yes, beautiful. And I think it’s important we continue to question both our motives and approaches to photographing the homeless. The more they appear on our streets, the more we instinctively tend to first look away, and then… resent them! So it’s more important than ever that people find new ways to reframe, rethink and hopefully reengage both our gaze and our actions….

A worker earning minimum wage in the U.S. would have to work nearly 127 hours per week to afford a modest two-bedroom rental home in most of the U.S.

Hi Stan, thanks for your thoughts. Smart, as always. And thanks for being a loyal reader for yet another year. We appreciate you!

Comments are closed for this article!