Just this morning, I was trying to explain Communism to a 9 year old.

Fortunately, he’s very bright for his age, and seems to be interested in history. But it’s still hard to break down planned economies, and the Bolshevik Revolution, to a person who was born on the cusp of The Great Recession.

Basically, I contrasted Capitalism, which is obsessed with extracting money and value from all things, with Communism, which intended to put ownership of the means of production in the hands of workers.

Karl Marx wrote thousands of words about the exploitation of labor by Capitalists. (It’s a rather famous book that railed against endless greed.) I told my son about how in practice, Soviet Communism meant the state had control over where you lived, what you did for a job, what you could eat, and where you could travel.

America, by contrast, offers freedom and choice. But in 2017, it’s pretty clear that regular people and the entire planet are cannon fodder for the big guns.

Cash rules everything around me indeed.

The Soviet Union collapsed, as we all know, and Russia is now a Capitalistic dictatorship. There may still be a Communist Party there, (I didn’t bother to check,) but if so, it’s one among many, and all are subservient to Putin.

But the Soviet Union was not the only major Communist power, of course. Not to be outdone by Stalin’s cruelty, Mao Zedong led a Communist revolution in China, in 1949, and eventually ruled over the massive, populous country for decades.

The upshot of Communism, supposedly, was that everyone would be guaranteed a place to live, a job, food, and time off. Theoretically, that would obviate things like homelessness, and it was meant to create a level playing field.

From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs.

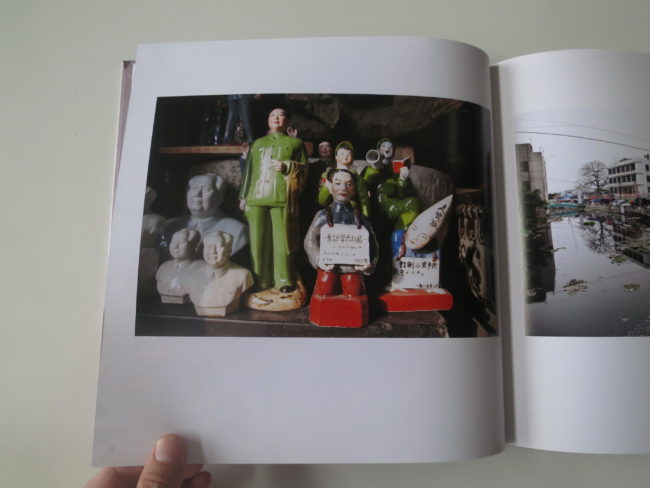

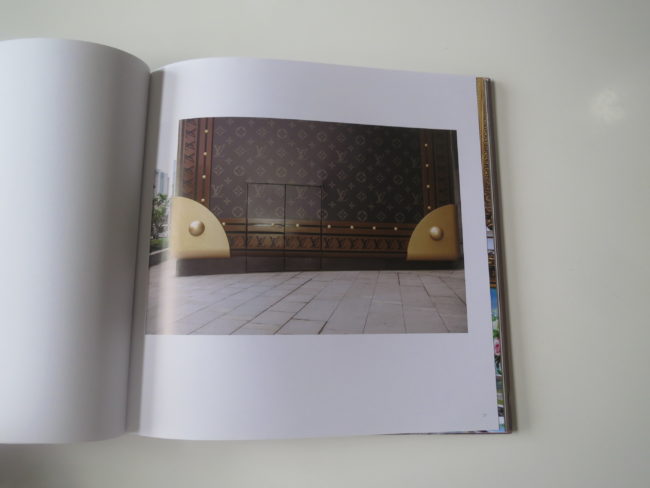

These days, though, China is Communist in name only. It has become a global economic powerhouse, and has begun to transition into being a political one as well. Capitalism is alive and well, in the Middle Kingdom, and its conspicuous consumption and income disparity seem rather familiar, if you ask me.

If the middle class in America continues to hollow out, we’ll be left with nothing but the rich and the poor. But in China, with their rapid development, hundreds of millions of people have been brought out of poverty.

Their middle class is booming while ours disappears, but still, the lifestyle difference between rural farmers and wealthy urbanites in China is still probably wider than in America at present.

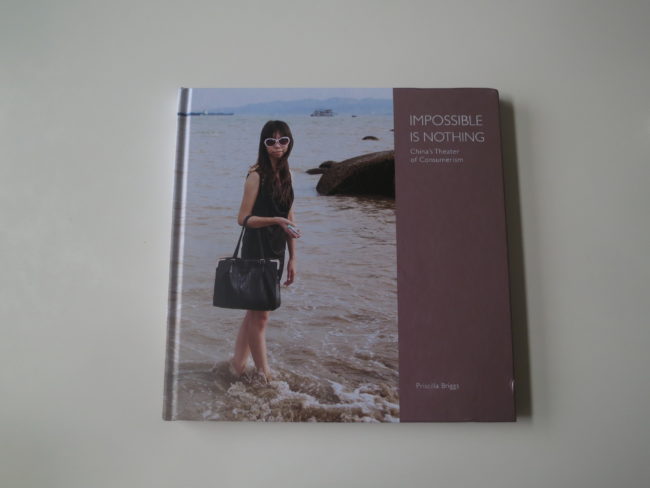

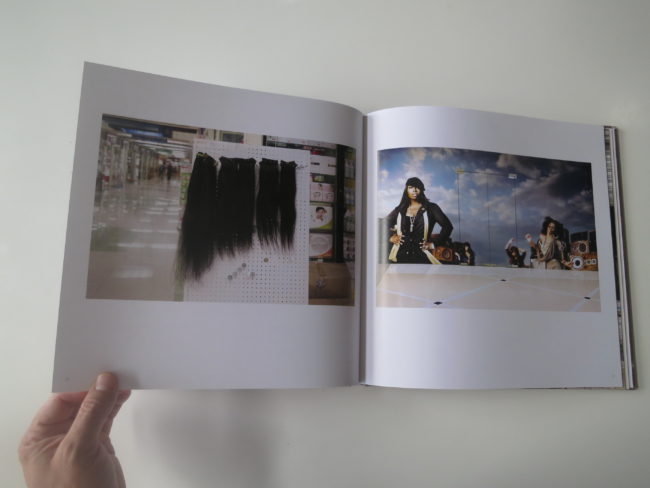

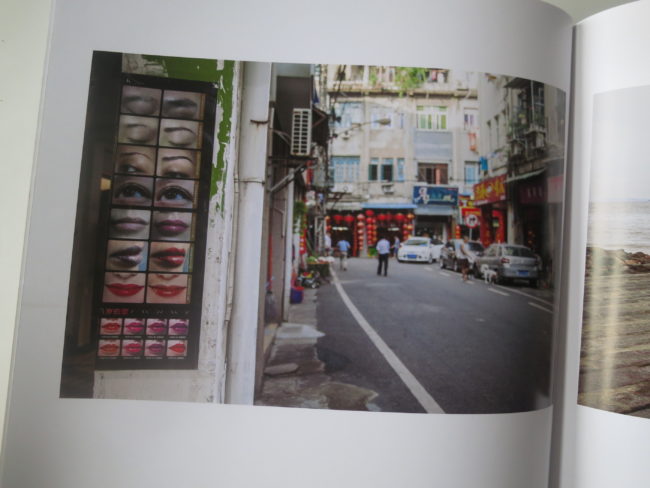

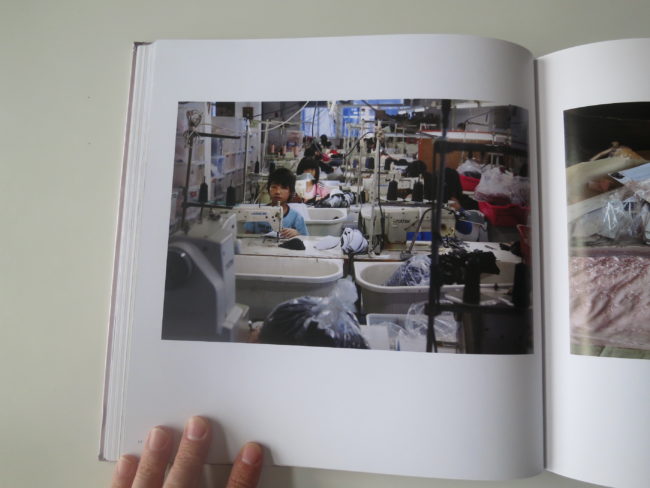

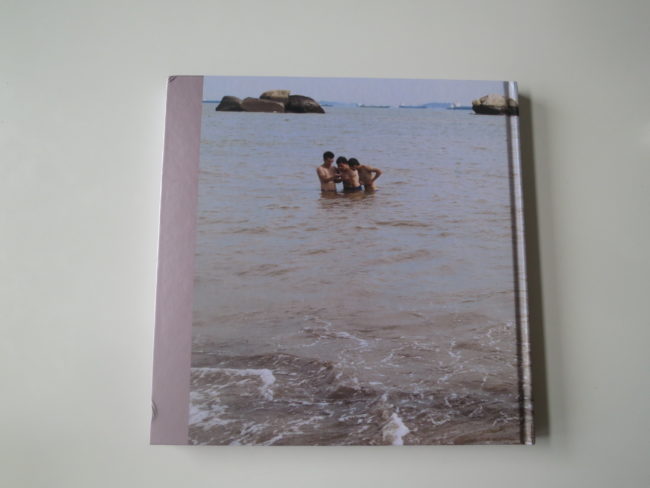

Consumption is all the rage in China these days, and I can say that with some confidence, having just put down “Impossible is Nothing: China’s Theater of Consumerism,” a new book by Priscilla Briggs, recently published by Daylight.

It’s funny, the way themes develop from week to week. Last Friday, I talked about that certain homegrown authenticity that projects have, when photographers work where they’re from. Aaron Hardin and Evgheny Maloletka made very different pictures, in the American South and Eastern Ukraine, but their photographs had that special sense of local juice.

Today’s book, by contrast, belongs to the far-reaching tradition of artists traveling to new places, camera in hand, and shooting what they see and explore.

From what I can gather, Ms. Briggs went to an artist residency in Xiamen, which likely kicked off her investigation. Regardless, the titles at the end confirm she shot in China between 2008-13.

I don’t mean to knock this book before I even get started, as the wandering eye can often bring a more distanced, perhaps critical view. Certainly, irony is often boosted by the outsider’s perspective.

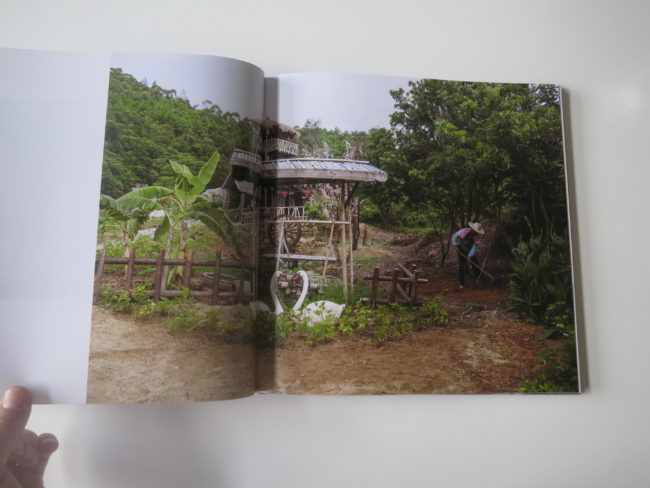

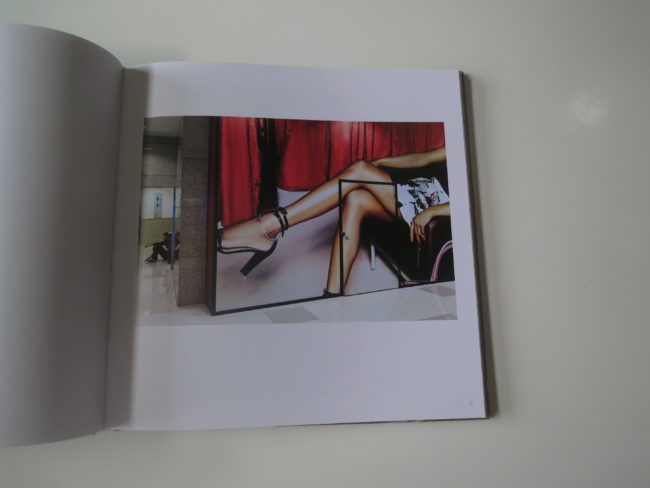

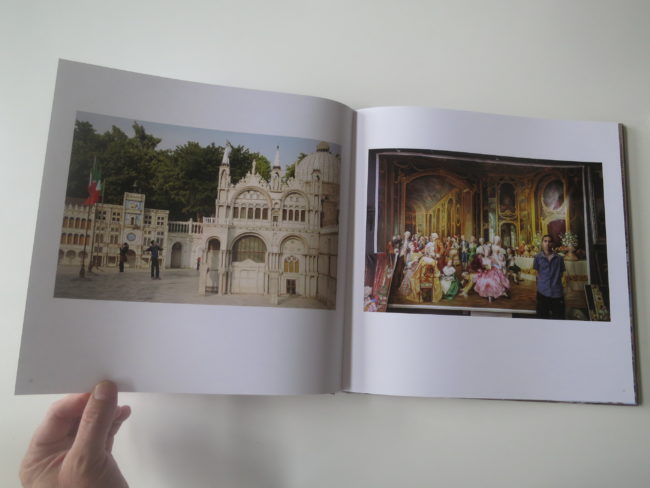

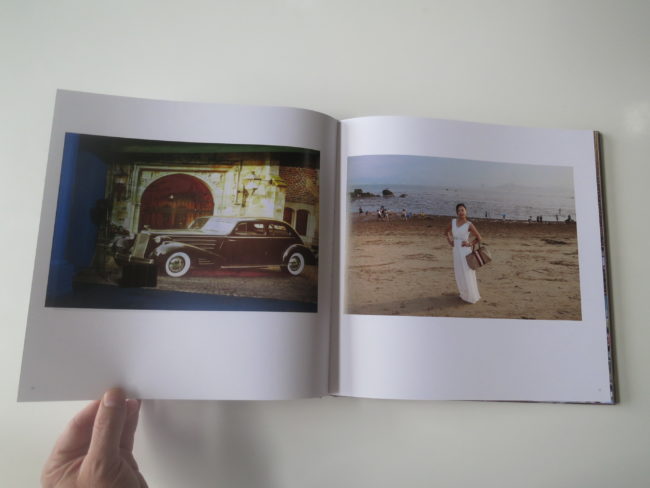

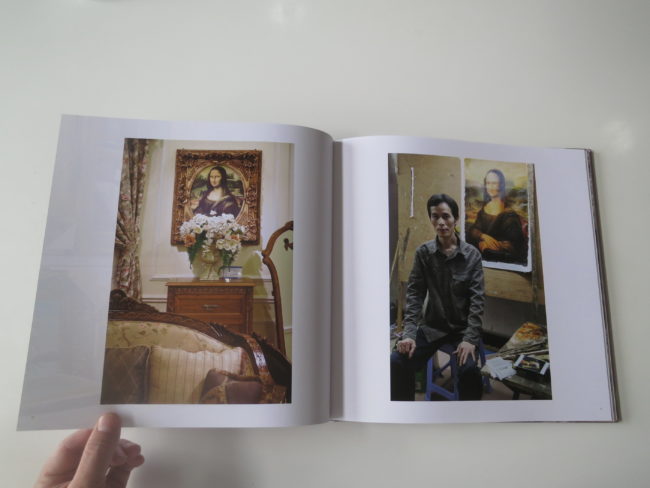

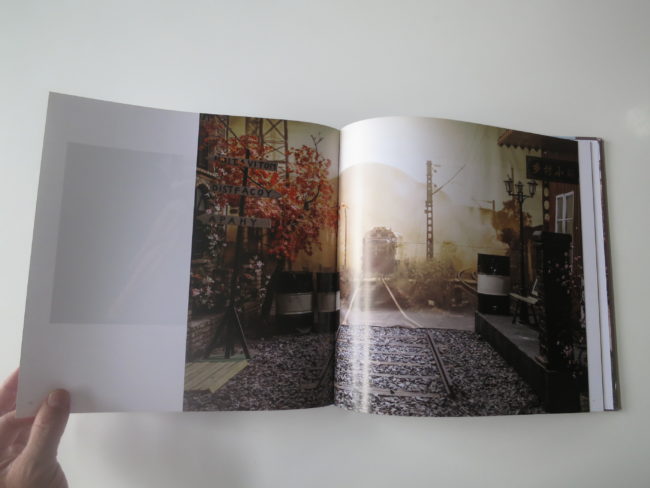

And that’s mostly what we get here. The series is heavily ironic, as the most prominent repeating motif is the backdrop. The fake world, enmeshed with the real thing, comes up again and again.

(In fairness to Ms. Briggs’ observations, after writing the column, I discovered this Ai Weiwei Op-ed, in which he calls China “a place where everything is fake.”)

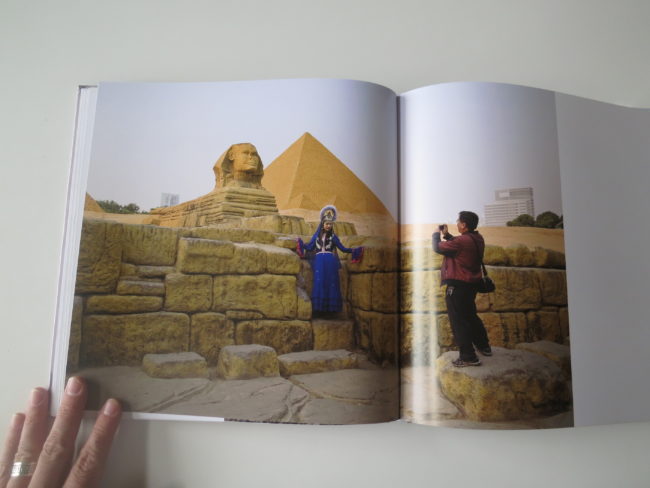

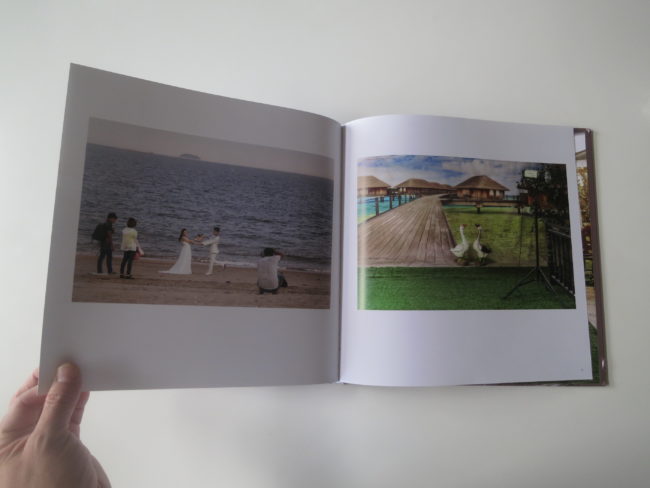

We see a real boat in front some very realistic-looking fake water, a park bench in front of a painted train car, which itself is in front of a virtual horse farm. Plastic geese before a faux Tahitian village. A fake snow scene, a fake tugboat, and a fake locomotive barreling down the tracks.

You get the picture.

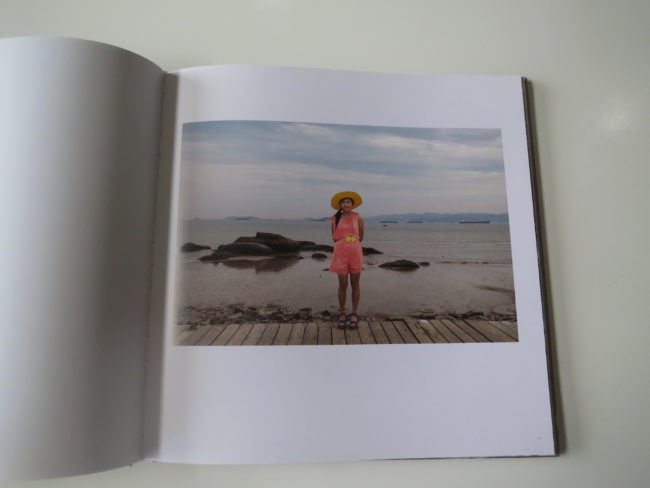

There are also amusement parks, clothing factory workers, and a subset of young women who she photographs before the sea. (Which is real, I think.)

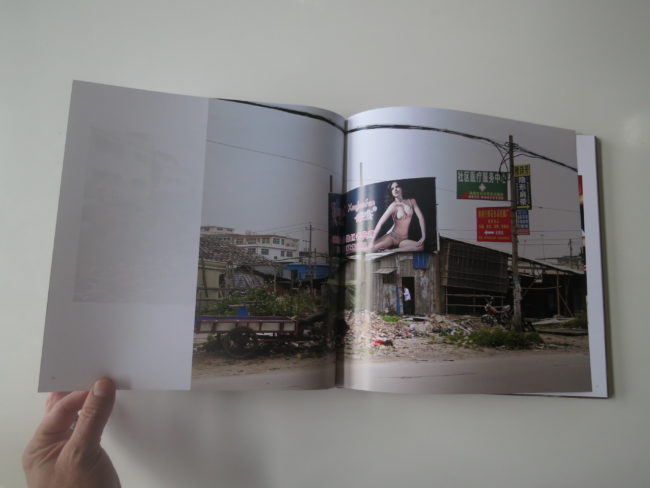

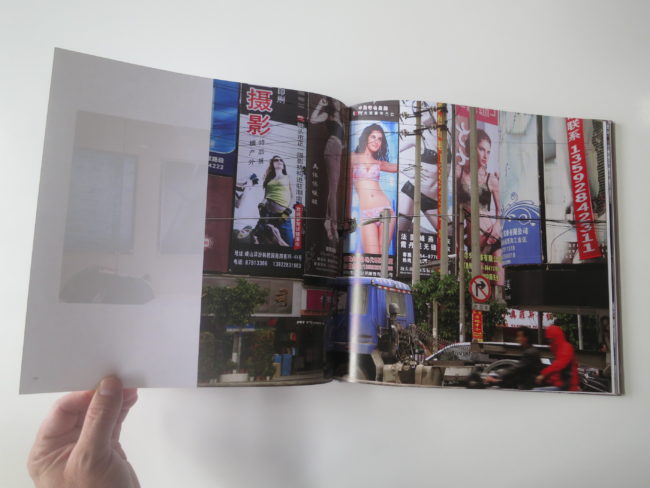

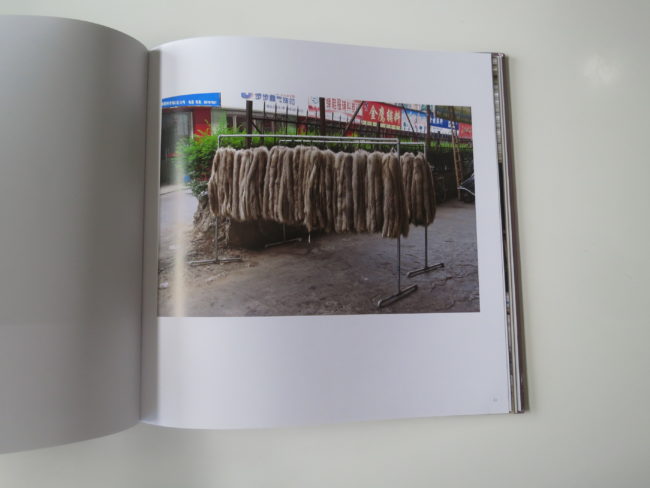

We’ve got hair extensions, fur coats, and pink lingerie that says luxury on it. And lots and lots of photographs of advertisements of women in bras and panties.

I mean lots of photographs.

Are the ads that ubiquitous in China, or is it something she zeroed in on to make a point? I’m not sure, since I’ve never been to China.

This is one of those books, though, that carries a clear point of view. It shows a tacky China, one that builds fake monuments from other places, (Hello, pyramid of Giza,) while simultaneously bulldozing its own history in an orgy of new.

I’m always interested in books that show me things I haven’t seen before, so this qualifies. It shows an absurdist strain of Chinese Capitalism, and I chuckled once or twice. The use of repeating motifs, and the way the edit is structured, shows me a lot of care went into making this book.

Well worth discussing on a Friday in June.

Bottom Line: Ironic, wry take on Chinese consumerism

Click here to purchase “Impossible is Nothing: China’s Theater of Consumerism”

If you’d like to submit a book for review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com