Jonathan Blaustein: So what’s going on down there in New Orleans?

Russell Lord: We are trying to get all of our schedules organized for the next three years. I’ve been here for about three and a half years, and as soon as I got here, we put a bunch of stuff on the books. I’ve spent most of my time working on those things, and we’re finally caught up and planning for the future.

JB: You hit the ground running, and you’re catching your breath now, three plus years later?

RL: Pretty much. The first show that I did here, which we were already committed to doing, opened less than two months after I arrived. And the first show that I did in its entirety opened less than six months after I got here.

So it was a very quick pace. It’s nice to have a moment to catch your breath.

JB: Basically, you’re saying that at your first opening, the security guards didn’t want to let you past the velvet rope?

RL: (laughing) They were like, “Who’s this guy?”

JB: Who’s this guy?

RL: It’s true.

JB: They don’t say that anymore, I’m sure.

RL: No. I’m no stranger to being here late in the evening, especially with a young child, as you know. Sometimes, the most productive hours are right after their bedtime, and into the wee hours of the morning.

Since I live so close to the Museum, I often come back around 7:30, and work until Midnight. I get a lot of writing done, in the quiet hours.

JB: Well, you’ve already given us one of your secrets, and we’ve barely begun. To be honest, I don’t do that. At 7:30, when the kids go to bed, I turn on the TV and put my feet up. That’s my only break in the day.

RL: I do too, now. But for the past couple of years, that has not been my schedule. I’m grateful to have those moments, alone with my wife, where we’re just able to relax. Preferably with a little bit of bourbon.

For a while there, when I was writing the Gordon Parks book, and when I was writing the forthcoming “Photography at NOMA” catalogue, and the Burtynsky catalogue, those were all things that were written largely on weeknights, between 7pm and 2 o’clock in the morning.

JB: That means if we were to parse your texts carefully, we would probably see a hint of loopiness. The 1am loopies?

RL: I think so. Yeah. Though I did try to temper those with the 9am-the-next-day-check-and-balance.

JB: All right.

RL: Around 1:30 or 2 o’clock in the morning, you do feel pretty confident about everything you’ve just written.

JB: (laughing.)

RL: And then the next morning, you come in and wonder who was in your office the night before.

JB: That’s your friend Mr. Bourbon.

RL: (laughing.) Exactly.

JB: There’s a lot of stuff I want to talk about with you. I think you are almost perfectly primed to give our audience answers to a lot of questions that people have.

We hit the ground running, today, but I’d love to cycle back to some questions about how you got started, and perhaps jump around a bit as well.

RL: That sounds great to me.

JB: I’m sure I won’t get everything right, but your lineage looks something like this: James Madison University, then you worked at the Yale Art Gallery, you went to graduate school at the City University of New York, for your PhD, you worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and then you jumped to the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Am I at least mostly correct here?

RL: That’s all correct. The only thing that I will be precise about… you said it precisely correct, but I didn’t finish the PhD. I am, technically, A.B.D.

JB: I D.O.N.T. K.N.O.W. what A.B.D means.

RL: (laughing.) A.B.D is the status that means “All But Dissertation.” It seems to have achieved this pseudo-official status. It means that if you start a PhD program, and you don’t finish the PhD, you may have had an extra six or seven years of schooling that other people don’t, but there was nothing to add to the name.

The A.B.D. status defines someone who has gone through all the course-work in a graduate program, and then usually passed some sort of critical exam, which in our case is an Orals exam. It’s a crazy process where we develop three bibliographies.

One is in your focus area, which for me was 19th Century French and British photography. Another bibliography in your major area, which was the long 19th Century. And another in your related minor, which for me was late 18th and early 19th Century American art.

JB: And by bibliography, do you mean that you have to present a reading list of everything that you’ve read?

RL: Basically, you come up with a list of things, about a year and a half in advance, of what you are supposed to read. And you come up with these bibliographies in consultation with your thesis advisor, and a council of two other professors. At the Graduate Center, this is the way it works.

So I had three professors basically approving the lists that I came up with. And in the concentration area, I believe it was a 10 page bibliography. So we can calculate what that turns out to be in terms of numbers of books, or articles.

But it was substantial.

In the major area, it was about a 5 page bibliography. In the related minor, it was a list of artists that we were expected to be familiar with. You are then responsible to read as much of that as possible.

At a certain date, you show up at the Graduate Center, and go into a conference room with the professors, and they start showing you slides. You have to talk about them, and they ask you questions, in a very directed way, so you can pull in some of what you learned from doing the reading.

What is particularly challenging about this test, is that it is designed to test the depths of your knowledge. So they basically ask you questions about each pair of slides that they’re showing you, until you can’t answer a question. You leave each pair of slides having just incorrectly answered, or been unable to answer, the last question.

You go into the next pair feeling really bad about yourself.

JB: I was quiet for a really long time, and there are so many things I want to say here that my brain hurts.

RL: (laughing.)

JB: I don’t know what to say to that. It sounds like a kind of torture. As opposed to a productive and positive plan of exploration.

RL: It’s a very interesting thing, because I think a lot of people certainly don’t like it. And a lot of people are more adept at other parts of the PhD process. For me, I actually saw a lot of value in it.

It’s a rigorous test, but I really got into this field because I had a great desire to be able to communicate things about art and culture to to a fairly broad audience of people. And I’m always very excited at the most academic things out there.

I’m interested in what people are saying in small, focused, academic circles. I like absorbing that information. But I like even more trying to translate that information for people who would never come into contact with those circles otherwise.

So for me, reading things like all of TJ Clark’s books, or some of the more philosophical writings. Derrida’s work on Art History, for example. And thinking about how to translate that information, and spit it back out and relate it to work. Trying to focus in on those kernels of truth for great ideas, and then bring them back out.

That, to me, is a challenge, but it’s exciting, and I think it’s a responsibility that we all bear. Especially when we decide to go into the curatorial world, because you’re even more a public figure in this world.

JB: I didn’t mean to impugn the acquisition of knowledge…

RL: No, no. I totally knew where you were coming from.

JB: Good. Because we live in the world of the hyperlink, and establishing two years ahead of time, every single book, and only those books, that you will read… it would be like getting a PhD in Jazz and never getting the chance to improvise.

RL: Right. Right.

JB: It sounds a little hollow. But you made so many good points, beyond the little stuff I want to make fun of. Other people who go through that process do it to end up in Academia, and never really stray from a very tight knit community of hyper-experts.

RL: Right.

JB: You knew all along that it was important to you to be able to take this knowledge down from the tower, and start talking to as many people as you could about what you love, and why you love it?

RL: Absolutely. I was aware that in academia, just to get through a PhD program, you are being taught by people who have chosen the academic route. So it’s always interesting negotiating or navigating how much you should make apparent what your goals really are.

However, I worked with several professors at the Graduate Center who were very excited at the fact that I was so committed and enthusiastic about working in the “object” world, and the Museum world.

What was exciting for me was that I got to become a nexus point for them as to where the two worlds might meet. I was just talking to Geoffrey Batchen recently, who was my advisor. He taught a class on 19th Century British photography, and at the time, I was working with Hans Kraus, and Hans let me bring a couple of really early Henneman and Talbot salt prints to class one day.

I remember Geoff saying recently that being in New York was a dream, as he’s since moved to New Zealand. He said, “It was a dream. I had great students, and how many places could you ever teach a class and have one of your students bring in Talbots and Hennemans.”

He was right. There was something really exciting to being in New York, and being surrounded by all these beautiful collections, but for me, there was something also very exciting about having people like Geoff Batchen training me, and being wholly supportive and understanding of what a museum can do, and what actual “object” study can do.

In addition to the book and the theoretical work.

JB: So even when you were immersed in that rigorous environment, you were already thinking about a connection point with a public audience.

I’m guessing it’s because you worked in a gallery environment at Yale. Does everything build upon itself? Or was there a seminal experience at some point in your career where you decided that was the direction you wanted to take?

RL: It was a lot of building upon the previous step, in most of the cases. But there were some defining moments.

When I got to Yale, I had a chance to work very closely with “objects.” I was hired as the Administrative Assistant in the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, and my responsibilities, on paper, were to be the department assistant. I would answer phones, do purchase orders, things like that. And also to take care of the collection.

JB: You were a desk jockey.

RL: Yes, but I would also pull works for study, and put them back. I ultimately ended up organizing classes. But then it moved far beyond that, to turn into a really wonderful opportunity where I got the chance to work with the Director, Jock Reynolds on a couple of exhibitions, and I co-ordinated the publication of Emmet Gowin’s “Aerial Photography” book.

Throughout that four year process, I realized what you can learn from looking at the “object,” and how much the physical qualities of the “object” can have a huge impact on even our theoretical understanding of it. Whatever we might think, or want to say in a general way, can often be upended by the physical properties of something itself.

JB: A print, for example.

RL: Right. So that quickly became a hallmark of my research: what the original “object” can tell us that a reproduction can’t. Ultimately, when I did decide to go to the PhD program, and I was thinking about what I wanted to write about, it started because I was interested in these weird physical objects, early photogravures, which it seemed like not much work had been done on.

And that proved to be true. No one had really explored why people were interested in photo-mechanical reproduction, from the very outset of photography. Nobody had really considered how pervasive

those attempts were. What my research tries to demonstrate is that photography has been written as a history of great images by great artists.

In the marketplace, we fetishize the unique version of each of those things. This is the best print because it looks, in this way, different from all the others. We play down its reproductive qualities, in favor of the uniqueness of the individual object. So the way the History of Photography has been written, to my mind, as I did my research, seemed to be at odds with its origins. Which were largely based in an interest in reproduction.

JB: How so?

RL: At least from Talbot’s perspective. And, even, perhaps, early on in Daguerre’s career, he was interested in the idea of reproducibility. And also the idea of hybridity. We tend to separate photography out as something different from anything else. In its earliest days, it was described as being hybrid. All the words people came up with to define it were themselves usually two roots from different fields, smashed together, like photo and graph.

I could list all the other kinds of names, like the heliograph, the heliogravure, the physototypephysautotype. But I’ll stop there. Niecephore Niepce himself has a page in his notebook where he describes a bunch of different combinations to describe what he’s trying to do. They all have these different roots, and it’s a wonderful exploration in lexicon.

JB: That would be fascinating to see.

RL: Beyond those kind of rhetorical devices, they were creating things that were, themselves, physically hybrid. Meaning, there was certainly a light-sensitive component to what they were doing, but it often resulted in an ink on paper print. Since I had this interest in looking at and showing “objects” to people, I started thinking,

“OK. If you are a person in France or England in the early 1840’s, and you keep hearing about photography, what are you actually seeing? How many people would have had the chance to see a Daguerreotype on display in a shop window, for example? How many people would have seen an actual salt print?”

One of my arguments in my thesis is that more people encountered photography in the photogravure, or photomechanical form, than they did in what wme call its pure form: The Daguerreotype or salt print. They saw prints in ink, produced after those other things, so for them, at a very early moment, there was a confusion as to what, exactly, photography was.

The word came to encompass all of these kinds of practices, and now of course it encompasses even more. It’s things on paper, or printed with ink, or on glass, or on metal. Now, photographs might have no physical, permanent form whatsoever. Things that might exist digitally, and affect and be seen by millions of people, but might never permanently exist.

JB: I couldn’t help but go to the digital world in my head.

It struck me almost immediately, when you were talking about what people encountered, versus what was fetishized… that is today. I think it’s a real problem that a lot of people scratch their heads at.

People’s obsession with the medium, has never been greater. In the last decade, we’ve minted a couple BILLION, or more, new photographers. Without exaggeration. But it seems like the interest, at least in the US, in well-crafted prints in a white frame, on a wall, the boutique aspect of unique objects, is fairly limited.

As you live in New Orleans, we can talk about how certain cultural meccas, at least, are outliers in that trend. I doubt you’ll disagree with me, and I’ll give you a chance.

It just seems like what you were fascinated by, at the onset of the medium, has never been truer than it is today. What’s your take on that?

RL: It’s absolutely true, and accurate, and I agree with that completely. It was, in many ways, an inspiration for my look into the origins. I was really curious about the debates we were having now, but much more succinctly than I just described it to you.

There were all these interesting symposia with titles like “Is Photography Over?” or “Is Photography Dead?”

JB: Right. Of course.

RL: In all of those cases, people usually failed to come up with what “It” is. What they were describing, and what it was that had died. Maybe there are some differences in the physicality of it.

It made me think about the same kind of debates that people were having at the origins of photography, and if you are going to define what it is that is different, let’s say you settle on a material explanation.

Photography was “this,” and now it is “this,” physically. But if you look back through the History of Photography, there’s never been only one kind of photography. There were Daguerreotypes at the same time as salt prints, and albumen prints. Photogravures. Platinum prints.

It’s always been a whole host of different kinds of material things. So why should we try to define photography in any kind of pure, material sense? It’s almost as if the only constant in its history has been change and transformation.

Perhaps, rather than declare things “dead,” or “over,” we should see the digital revolution, which is PROFOUND, as just another step in a constantly evolving field of image-making.

JB: Right. And maybe it’s always been constant that photography has been shunted to the side, or considered distinct from other expressions of art, and other forms of media?

RL: Yes. Absolutely. Again, I think that’s a function of its origins. People said it was “kind of” a form of drawing, but it was drawing that performed itself. There was no human needed. It was auto-genetic, or…

JB: It was science, really.

RL: Yeah. There’s a great thing about the way people describe the process of photography. I mean, Talbot himself published a wonderful book illustrated with actual photographs, called “The Pencil of Nature.” Here we have Nature with a capital “N,” drawing her own pictures. There’s no person needed.

That was certainly one of the key components of photography. People settled on the fact that there was no human intervention, and I think that ultimately gave rise to mistaken beliefs about its truth or accuracy.

But Talbot publishes a treatise, and the title is something like “On the art of photogenic drawing, or the process by which objects may be made to delineate themselves.”

Amazing.

JB: And right now, of course, you’re proving the inherent value of the 10 page bibliography. Because you did read your books, and you have assimilated your information.

RL: (laughing.)

JB: (laughing) If your teachers are reading this…

RL: I think that’s what’s interesting about it is that you need to absorb all this stuff, but your jazz analogy is a really interesting one. It’s almost as if you are a jazz musician who is asked to just internalize the whole history of music, and, in three hours, give an improvisation in which little references to these things come out. You know?

That’s ultimately what it is. They just want to hear how you speak about these things, and how you can package theory or critical statements in a way that relates it to what you’re looking at.

For me, I saw a lot of value in it, and I was really glad that I read a lot of those things. At the heart of it, I’m really just a total nerd. As you can tell.

JB: Everybody can tell now.

RL: (laughing.) And there were so many books that I never would have read that now are some of my favorite books in Art History. And I wouldn’t recommend them for everybody, but for me they were incredibly influential, and I loved the ideas. Thinking about re-staging those ideas, or engaging with them in a new way is something that I’ll probably be doing forever.

JB: People will only read this. We don’t do podcasts yet. But your passion is definitely jumping through the speaker. The readers will have to trust me that you’re fired up and ready to do.

RL: Good. Good.

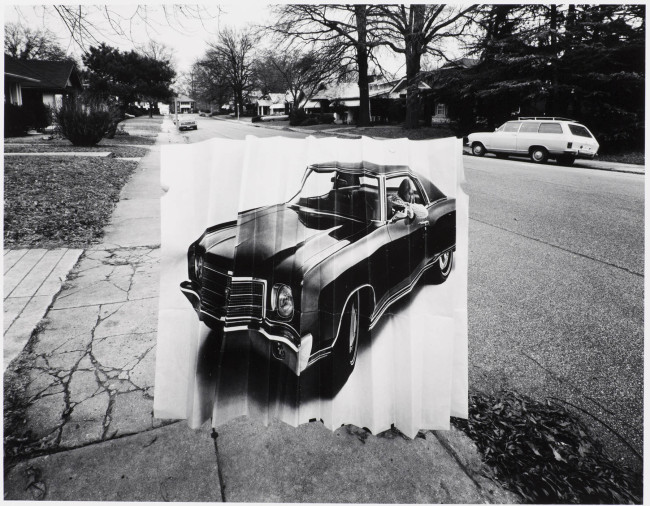

American, born 1940

Tricycle, Car Ad, and Sneakers, Part of Flying Objects Series, 1974

Gelatin silver prints

Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts, 75.235, 75.236, and 75.237

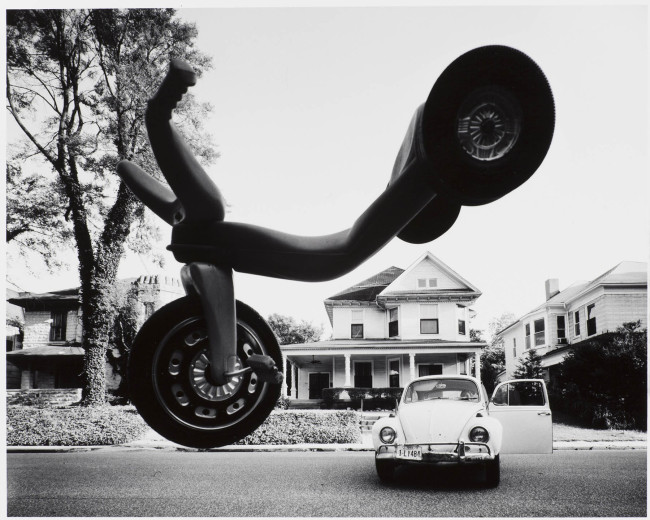

American, born 1940

Tricycle, Car Ad, and Sneakers, Part of Flying Objects Series, 1974

Gelatin silver prints

Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts, 75.235, 75.236, and 75.237

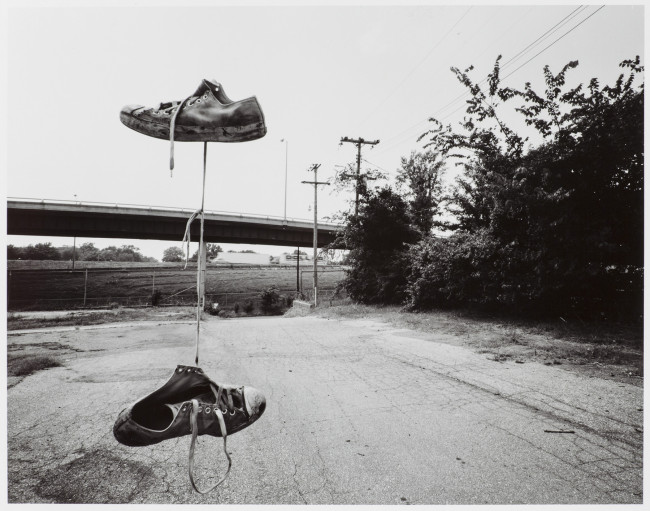

American, born 1940

Tricycle, Car Ad, and Sneakers, Part of Flying Objects Series, 1974

Gelatin silver prints

Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts, 75.235, 75.236, and 75.237

1 Comment

We are so lucky to have Russell here in New Orleans! His deep knowledge of photography continues to manifest itself in the wonderful exhibitions he is doing at NOMA. And a nice guy to boot.

Comments are closed for this article!