Growing older isn’t sexy.

(And it isn’t always fun.)

I rolled my eyes in deep mockery when I heard the millennial term “adulting” for the first time. As a bona fide adult, (with two kids, a mortgage, student loans and car payments,) I thought it was a cheeky way to trivialize how hard it is to keep all those balls in the air at once.

But as I thought it over, I realized it was kind of an absurdist word for an absurd concept.

Growing up.

Most people stop growing, physically, by the time they’re 18. Just yesterday, in the newspaper, I saw an 18 year old referred to as a “man.” Personally, I’d say an 18 year old boy, or a kid, but the Santa Fe New Mexican obviously disagrees.

People can grow, physically, by getting fatter or building muscles, but we mostly use it to refer to the process by which we get taller, and then it stops for a while, before we begin to shrink.

But growing, emotionally, is a process that need not be bound by age. Rather, in my experience, it’s a mentality.

Are you willing to look carefully at your flaws and weaknesses?

Are you willing to admit when you’re wrong and apologize meaningfully?

Are you curious about how your life might look if some of your flaws became strengths?

It’s that kind of attitude that allows people to grow, no matter their age. And it can take positive forms too, of course.

What have I always been dying to learn?

What would I like to try before I die?

Where am I desperate to visit, and am I willing to move mountains to make it happen?

You get the point.

Personally, I like being 44. Since I turned 40, I committed to a 4 year stint in therapy, (which I recently wrapped,) and have also invested in exercise and martial arts.

I’m fitter, happier, healthier and stronger than I was at 40. Or 35. Or 30.

I’m not saying I’m perfect, because lord knows I’ve made mistakes, (and pissed people off along the way,) but when I know I’m wrong, I say I’m sorry.

And as a part of “growing up,” I’ve found it fascinating when I revisit certain things, or ideas, and see them completely differently.

Take today’s book, for instance.

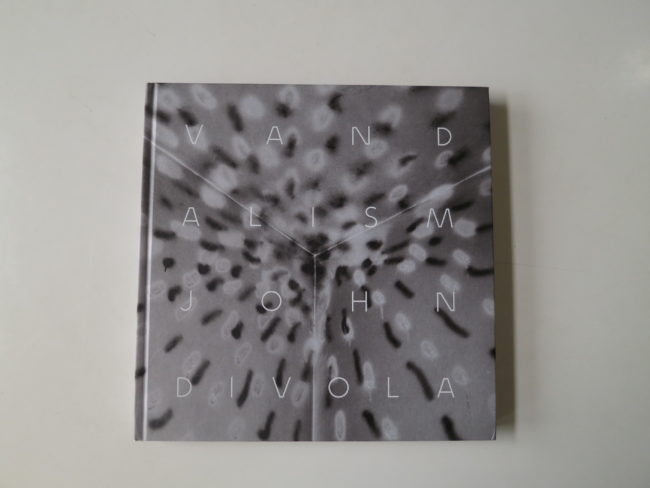

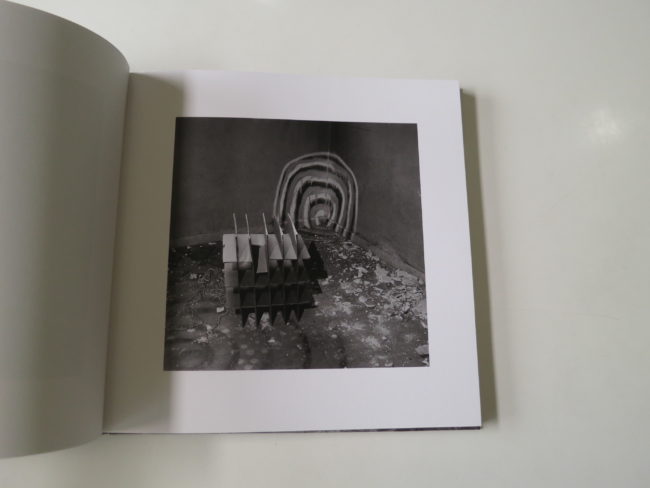

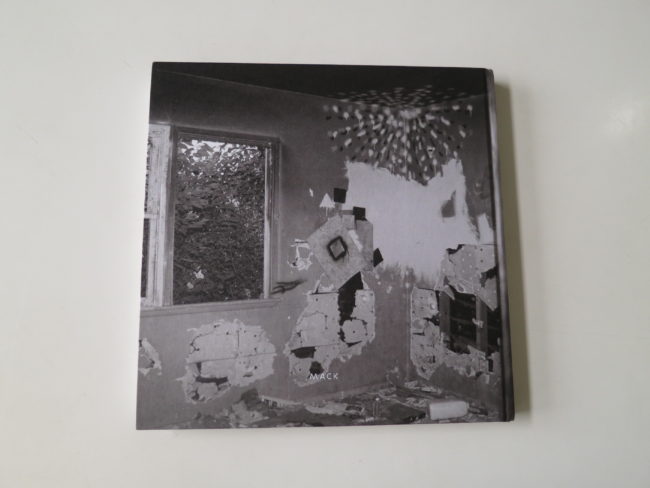

“Vandalism,” by John Divola, was published this year by MACK in London. I was excited when I heard it was imminent, because I’ve loved this project from the first time I saw it, and happen to know the artist as well.

I was fortunate to interview John about these pictures for a VICE story two years ago, and it was one of the few interviews I’ve ever done where I was consistently wrong-footed.

This dude was one step ahead of me, for most of the conversation, and never gave the answers I was expecting. Much of the time, it seemed like he thought my ideas about his work were hopelessly naive.

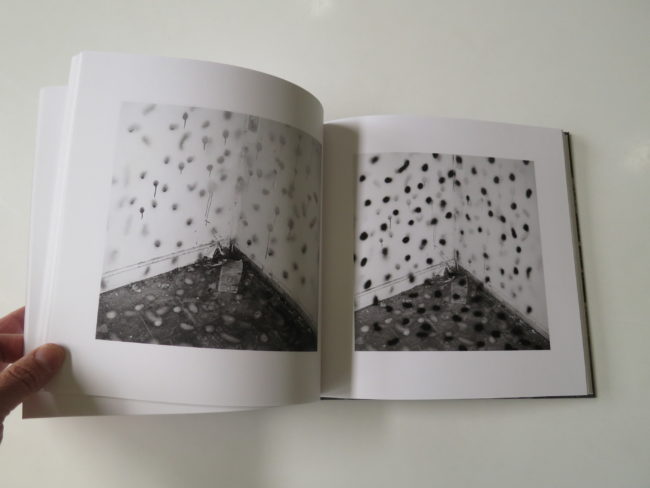

I saw the pictures in “Vandalism,” many of which are collected in this book, as an act of anarchic, early West Coast Punk and Graffiti art.

They were made in 1974-75, just as I was born, and from the contemporary perch, they perfectly channeled that sensation of breaking things to parallel a then-breaking America.

The pictures became counter-culture counterpoints to the gas shortages, Nixon and Carter, Vietnam, and America’s diminished standing in the world.

They felt like a colossal “fuck you,” and anyone who’s been a teen-ager can relate. (Or a rebel. Some of us are, some are not.)

John Divola told me I was way off.

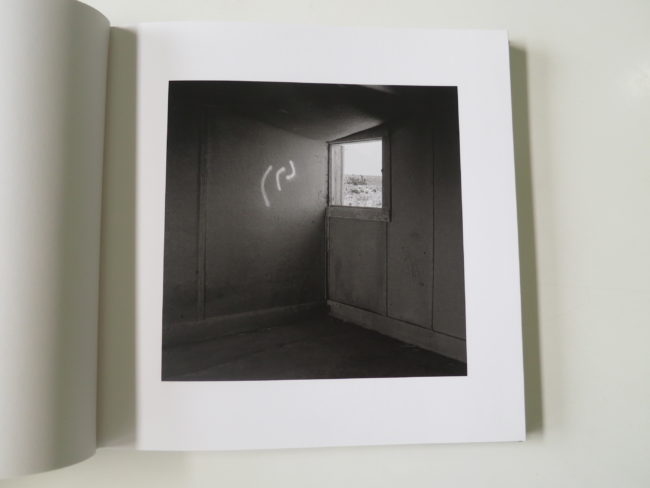

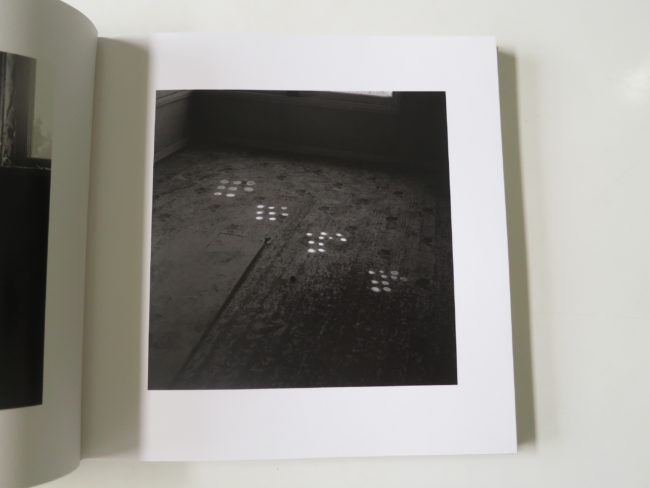

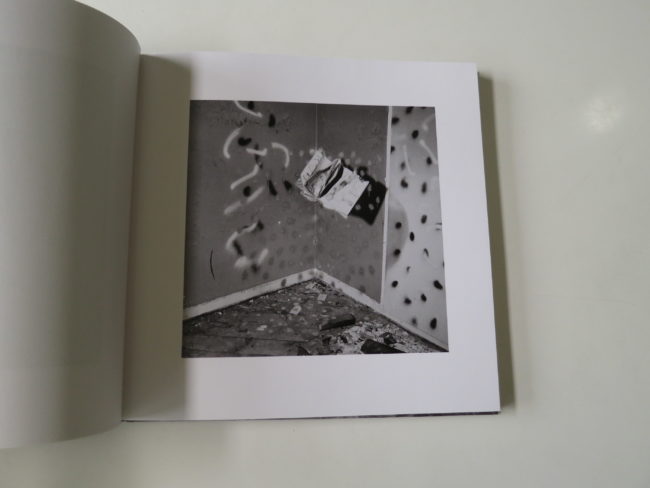

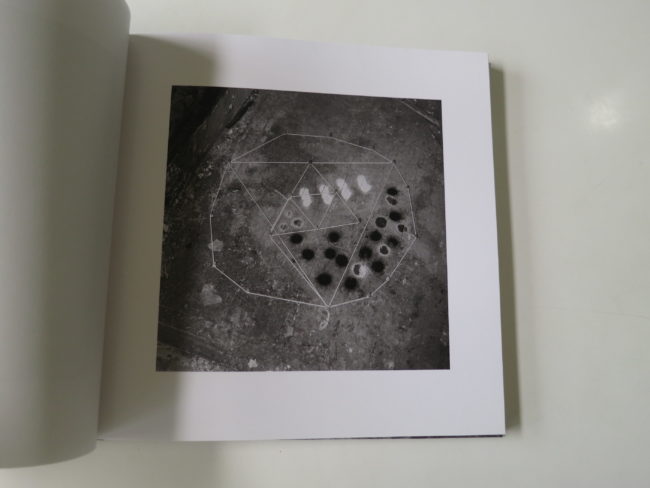

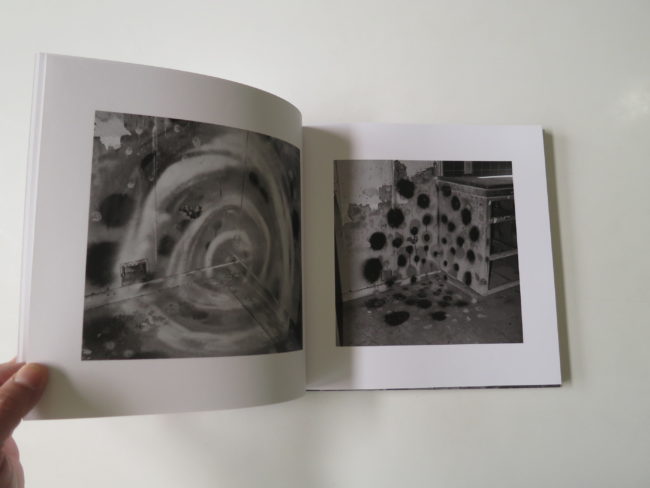

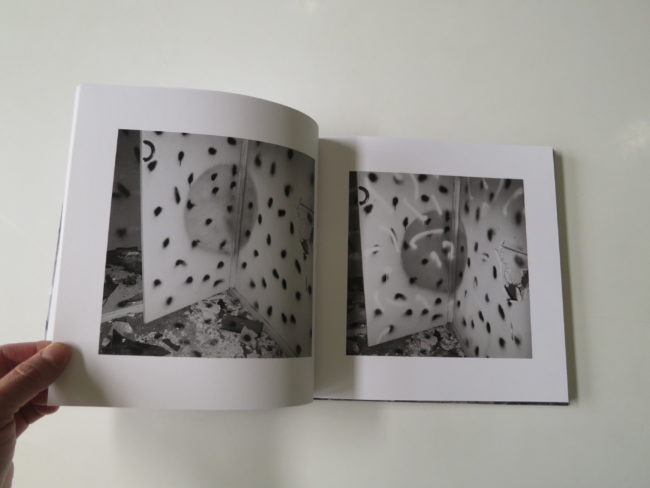

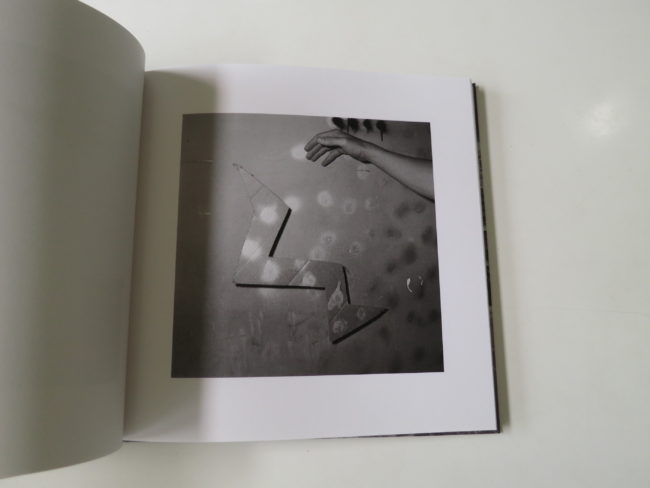

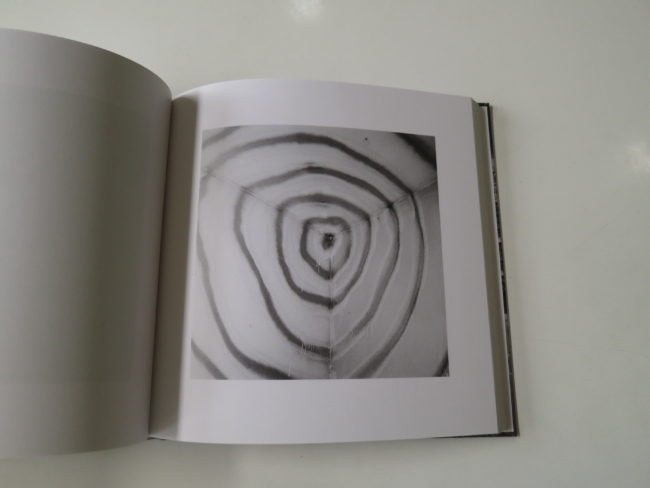

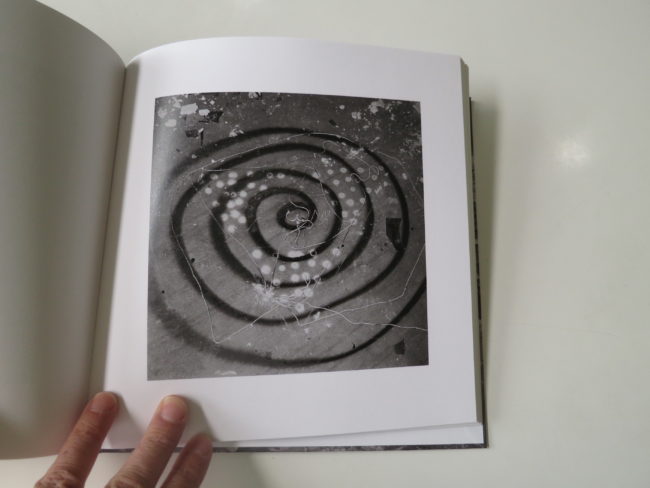

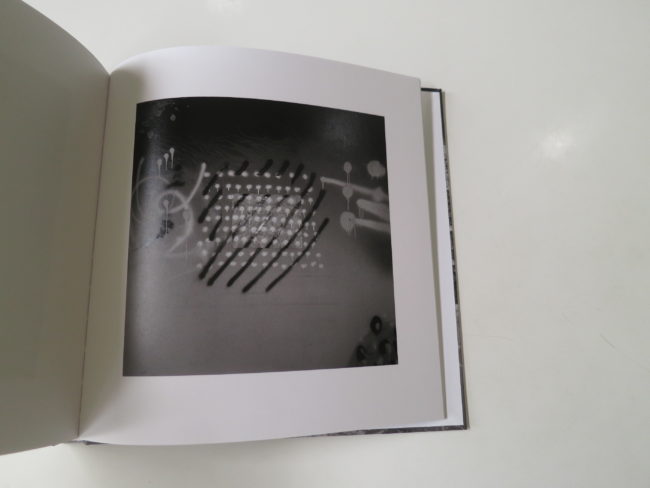

It was all about mark-making for him.

It was about the abstractions.

The shapes.

The interventions.

The act of painting.

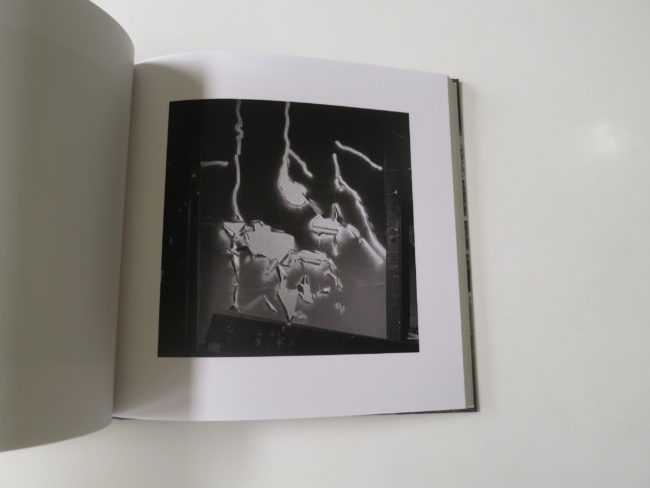

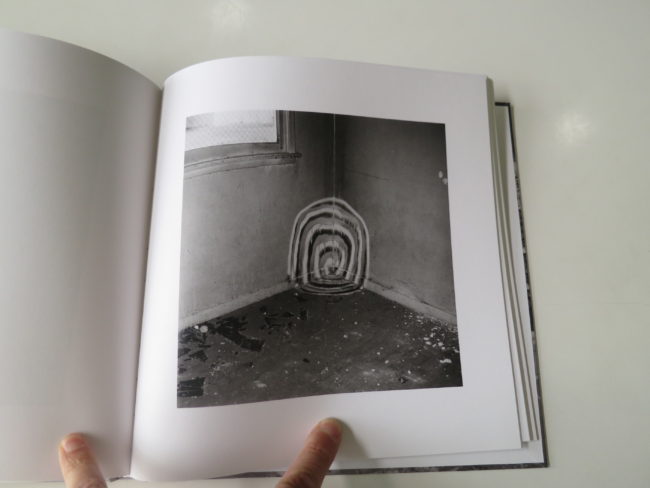

In this read, the pictures are documents of events and actions. The homes were well and truly abandoned, so it’s not like the graffiti was affecting anyone’s property.

Rather, they’re pictures that capture the actions of a heady, well-trained art student. A SoCal boy who went to good schools, and exercised theories while Zenning out and making abstract art in quiet places. (Which he still does.)

Though I eventually realized I was talking to an incredibly bright, talented, cool legend within the field, I still didn’t get where he was coming from.

I was sure I was right, even though it was his freaking art.

Needless to say, when I opened “Vandalism” this morning, and went page by page, I could only see it his way.

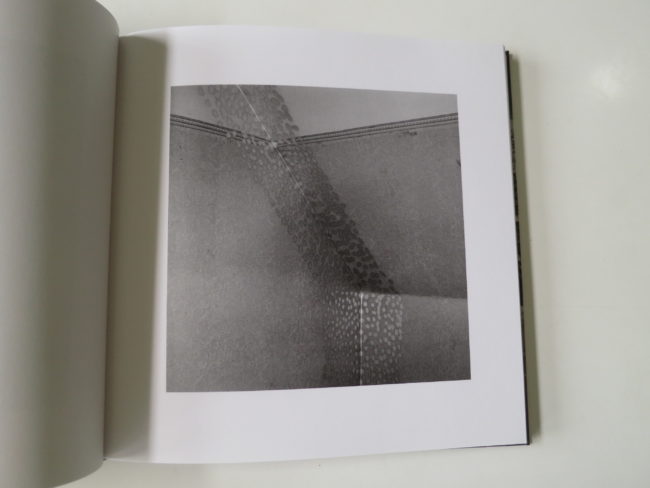

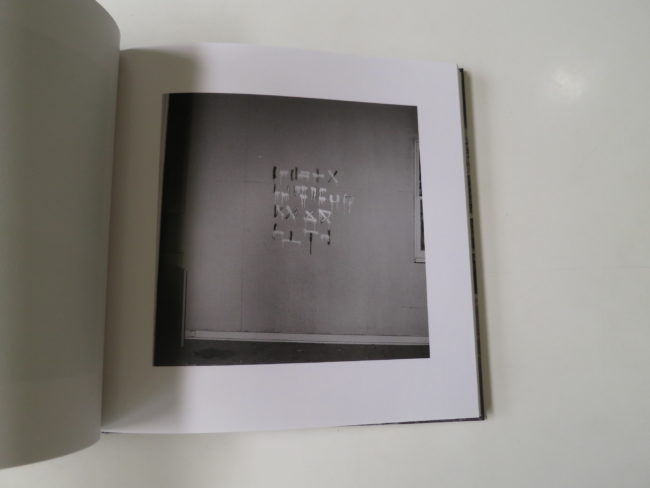

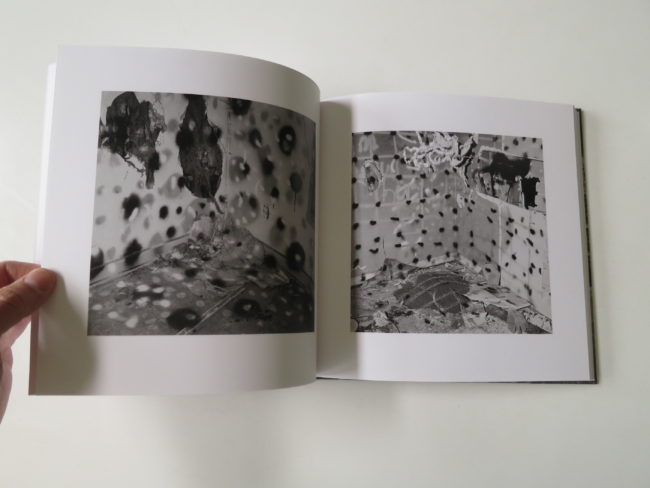

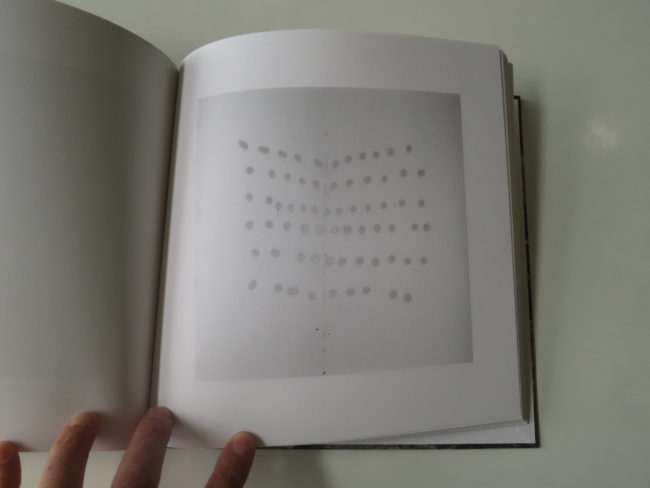

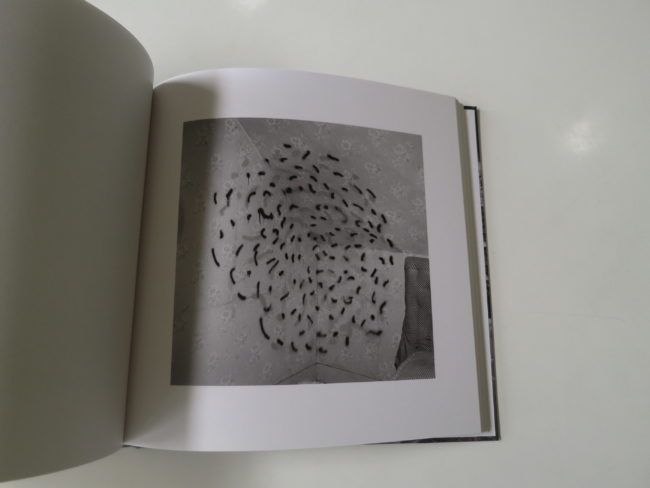

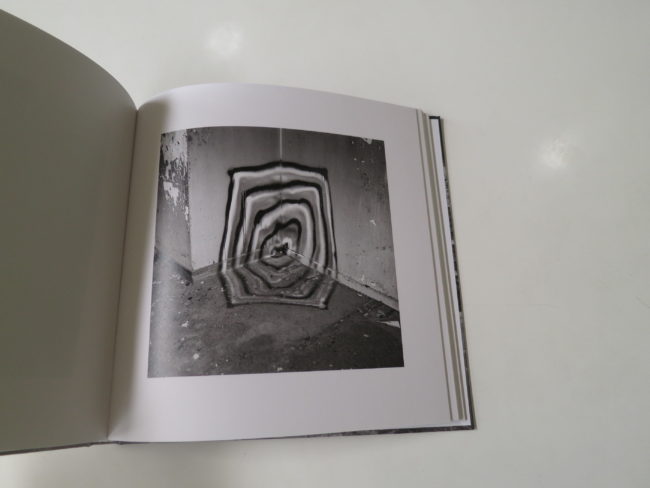

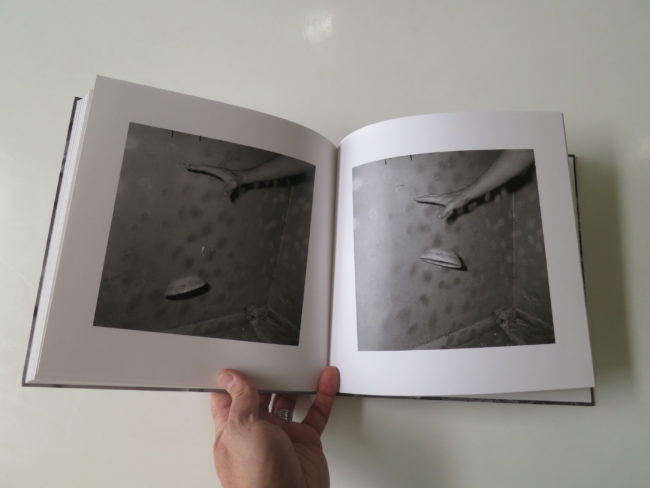

Shapes after shapes. Circles and patterns. Bulls-eyes and spirals.

Again and again.

The background, the houses themselves, with their dust and their rot, recede into the background. They become stages for the young artist who was playing with circles like a latter-day Malevich; these wall-forms competing for attention with the ghosts who roamed the halls.

In fact, while I appreciate the work differently, and perhaps more now, it was that sense of repetition that actually became the book’s Achilles heel.

MACK is rightly known as one of the best photobook publishers in the world. They make beautiful objects, and Michael Mack told me here in the column, in 2012, that they see the books as art pieces themselves.

I get that.

The production values here are phenomenal, as the tonal range of the images really comes to the forefront. There are no essays, or any text really, so that Zen vibe is strengthened by the quiet and the minimal design.

All to the good.

But in books like this, (and others I’ve seen them do,) I feel like the narrative becomes a record rather than an experience. It’s a collection of reproductions of important art, rather than a story to be unlocked, or a trip to be taken.

It’s not that I have such a short attention span, but as I look at and review books every week, I’ve come to appreciate the ones that try to vary their approach to keep me guessing.

It’s no different from the way most filmmakers use suspense.

I’m sure the book was produced this way intentionally, and as I said above, there are benefits to this approach. But as much as I like to focus on the details within each picture, after 50 of them, the eyes do begin to glaze.

Perhaps I’m quibbling, but then again, the other approach, which we’ve seen recently with reviews like “War Sand,” can also be pushed too far, resulting in mish-mash books instead.

Because “Vandalism” is spare, I’ll finish with my current, 44-year old version of why these pictures are so Rad.

The world often feels like it’s straight-up chaos. Pure insanity. It may always be crazy out there, but some time periods are certainly more rambunctious than others.

2018 is 50 years after 1968 and 100 years beyond 1918.

Whether you like round numbers are not, the symmetry with other times of great upheaval is difficult to miss.

But there is still order, and stillness, and quiet, even in the craziest of times and places. These photographs speak to that sense of order within chaos, because that’s exactly what they present.

In these sad, weary, abandoned spaces, shapes and patterns don’t just emerge.

They declare.

They stand proud, in their ugly beauty.

The creative act, and its aftermath, will continue to survive while are there are people alive to enact them. John Divola’s photographs in this project are twisted, hipster-youngster-driven-cave-paintings.

And I love them.

Bottom Line: A classic project, brought back from the 70’s

To purchase “Vandalism” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are particularly interested in submissions from female photographers, in order to maintain a balanced program.

2 Comments

great book.

I think art critics in general are frequently guilty of putting a lot more into things than were ever imagined- sometimes they are, in fact, incredibly observant, sometimes just incredibly verbose with an overriding need to prove. You can say the same for many an artist statement.

FWIW, I think Divola’s San Fernando Valley one of the greatest photo books ever…

Comments are closed for this article!