Within the African-American community, the idea of reparations is a popular one. (As far as I understand it.)

The plan, which calls for a massive payment to be made to all African-American descendants of slaves, is not without precedent, as West Germany paid reparations to Jews after World War II.

After hundreds of years of breaking up families, and precluding community from emerging naturally, the actions of Southern Whites are still felt today, and can explain the vast chasm in income inequality that exists.

It’s also an idea that gets lots of Conservative White People angry as hell, as it contravenes their sense of “individual responsibility.” Not to mention, money for reparations would clearly come from taxes on all other Americans, including White People.

Hopefully, most of us have seen Dave Chapelle’s hilarious skit on Reparations, or the one with Clayton Bigsby, the blind, black white supremacist. Chapelle used humor to both present these ideas, and also slough off any sense that they might happen IRL.

Some ideas are too radical to seem possible even in the 21st Century.

Short of the US Government dispersing Billions of dollars to try to level an unequal playing field, it is often left to individuals with power to do what they can to boost those who come from less-privileged circumstances.

If Diversity Matters, but is hard to achieve without concerted effort, then it makes sense to pay attention to the people who are putting their money where their mouths are. (So to speak.)

In this case, I’m thinking of the New York Portfolio Review, which is presented by my editors at the NYT Lens Blog, in conjunction with Photoville’s Laura Roumanos, and hosted by the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism in NYC.

I attended the event on Saturday, (and am still discombobulated as a result,) and am here to report that the Lens team has responded to contemporary circumstances with full force. Long-time readers know I’ve been there before, and have reported on previous attempts to build a diverse community.

It is admittedly a rough count, (and I could be wrong,) but of the 100+ photographers in the room, I only encountered 2 White American Males, and I was one of them. (I also counted 3 White Non-American Males, though of course there were likely more, as I was busy attending my reviews.)

Every other photographer I met, saw, or reconnected with was female, a person of color, or both.

In other words, almost everyone there was a Non-White-Male.

It was as if to end the privilege enjoyed by White Guys over the years, the Lens team made an effort to give almost all the slots over to those who have been ignored for so long.

We’ve all seen the statistics from Women Photograph, and other organizations, showing how disproportionate the jobs are in favor of the group in power.

Here, the script was entirely flipped.

It was done on purpose, obviously, as Jim Estrin and David Gonzalez are fierce advocates of supporting minority communities and women.

All to the good, as far as I’m concerned.

But as a reporter, I do have to mention the one Achilles heel of such efforts, at least given what I noted in person: almost everyone congregated into easily-observable groups defined by their skin color or likely area of origin.

All around the room, the pockets were visually obvious. Gaggles of people together, with very little cultural diversity within each group.

As an example, there was a moment when I was waiting in line for lunch. (Free Pizza. Hard to beat.) The young woman behind me appeared to be African, and I struck up a conversation.

When she said she was from South Africa, the African-American guy in line in front of me immediately turned and said, “Your from SA too?”

I interjected, “You’re from South Africa?” (He lacked the accent.)

“No,” he said, “but I was there recently.”

The two began speaking rapidly about the country, and his experience there as an African-American. He told how people were constantly trying to place him by tribe, and how he never felt he knew himself until he went to Africa.

I asked questions, as the two of them understood each other so easily. They told me that there are 11 tribes in the country, and they’re easily distinguishable by skin color, style, but more importantly by their vibe. Apparently the Zulus are most aggressive, and end up doing a lot of taxi-driving work.

I continued to ask questions, but almost imperceptibly, the two began talking more to each other. Finally, I realized I was not in the conversation at all, and turned to talk to the woman behind me, who was white, and lived in the mountains of the American West. (Like me.)

Behind us, two women of South Asian descent spoke in another pair.

While no one would have been the wiser, inside, I was disappointed, as I’d clearly tried to break beyond the boundaries that pervaded the room, and while it worked for a minute or two, that was it.

(To be clear, I had many conversations with people of diverse backgrounds all day long, from a Korean guy from Argentina to an Afro-Colombian woman from Brooklyn, because I like to talk to people, and see my efforts as reporting for you.)

Rather than suggesting there was fault on the part of the organizers, I’m sharing my observations because I think it pushes the ball further down the field.

It’s difficult and vital to get people in the same room. But perhaps it’s also important to then go one step further, and create organized activities that force people to get out of their own comfortable micro-communities, and talk to each other across boundaries?

When you think about it, it says a lot about human nature that racial divides are still as prominent as they are in America in 2018.

We evolved as tribal species, Homo Sapiens, and survived for eons by sticking with our kind. It offers safety, and understanding, but also allows for a kind of intra-cultural blinder phenomenon that can lead to evils like the Holocaust, or African Slavery.

The pre-Civil War South likely contained some “very fine people,” but collectively they came together to perpetuate monstrosity on a GRAND SCALE.

And we suffer from their actions still.

Why am I talking about the Civil War again? Haven’t I written enough about race relations these last few years?

Well, (as usual,) I’m glad you asked.

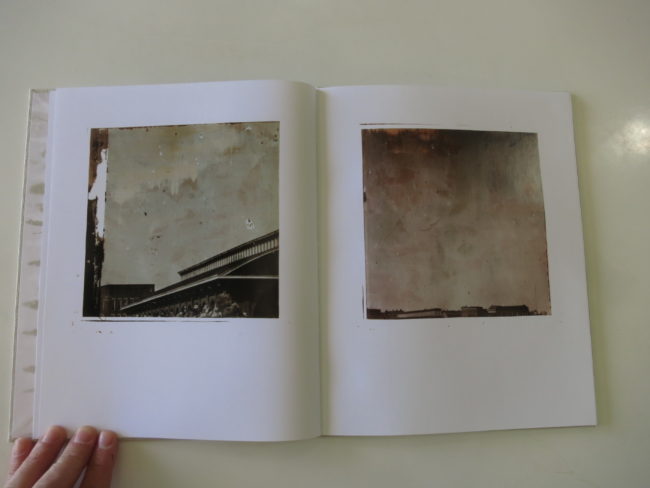

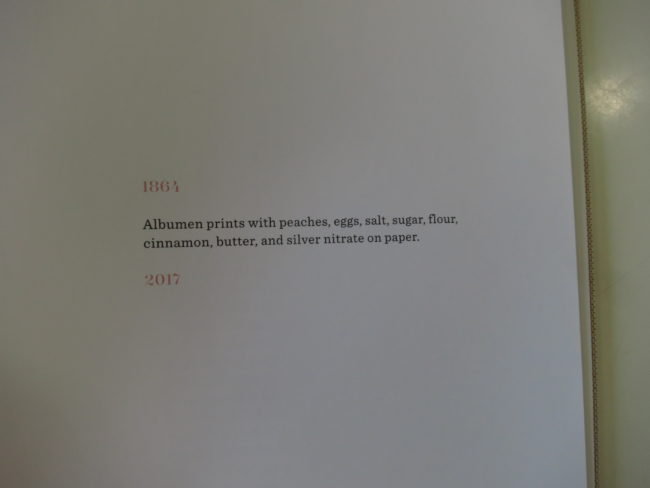

This morning, I spent some time looking at the excellent “1864,” a new book by Matthew Brandt, published by Yoffy Press in Atlanta. (With a nice essay by High Museum curator Gregory Harris.)

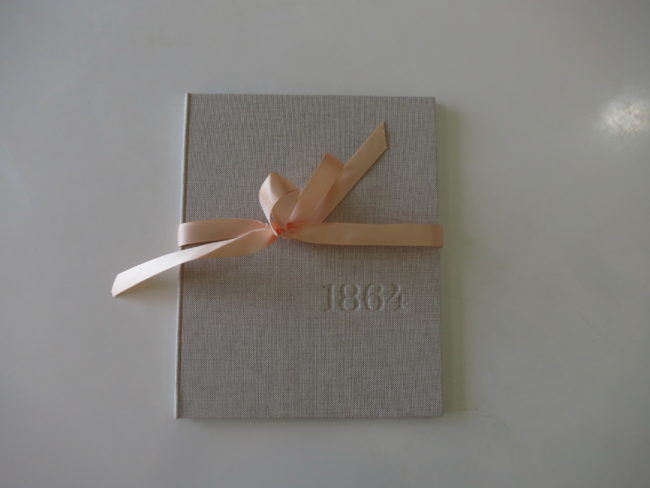

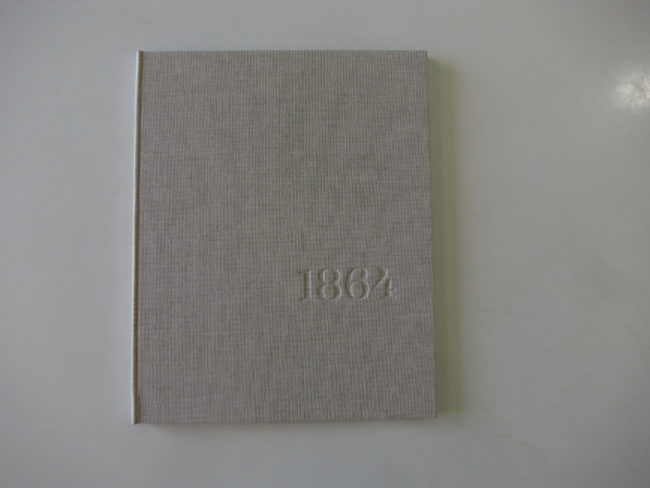

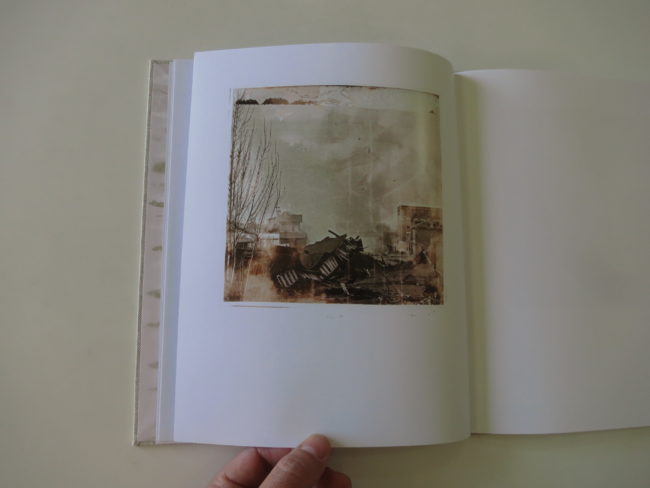

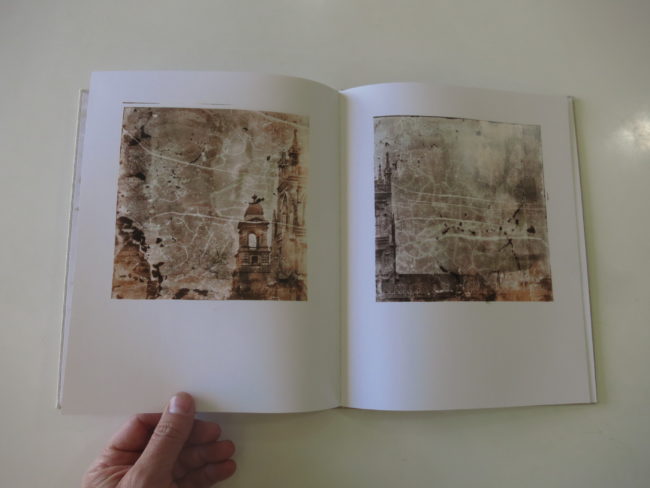

“1864” is a book that takes its pacing seriously, as it comes with a peach bow tied around it, (hinting at the contents within,) and then shows a couple of plates to whet the appetite, before explaining itself with the aforementioned essay.

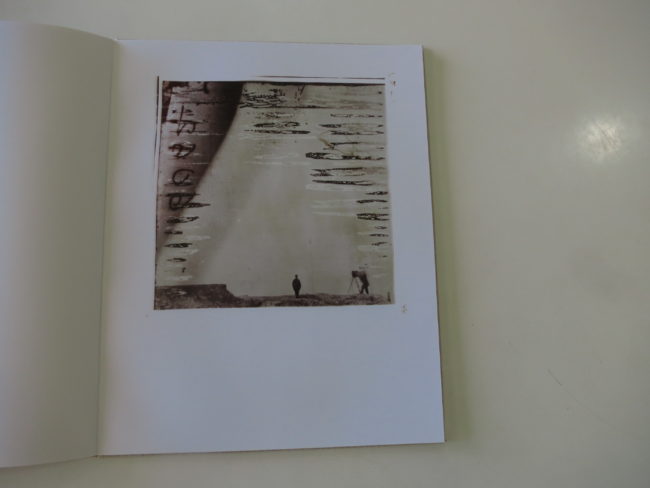

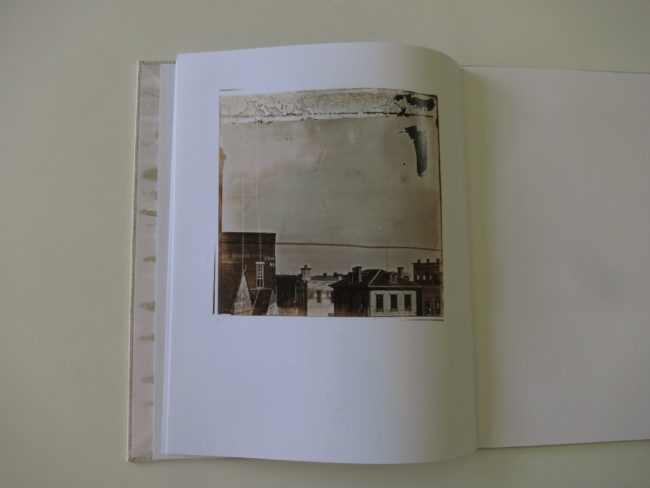

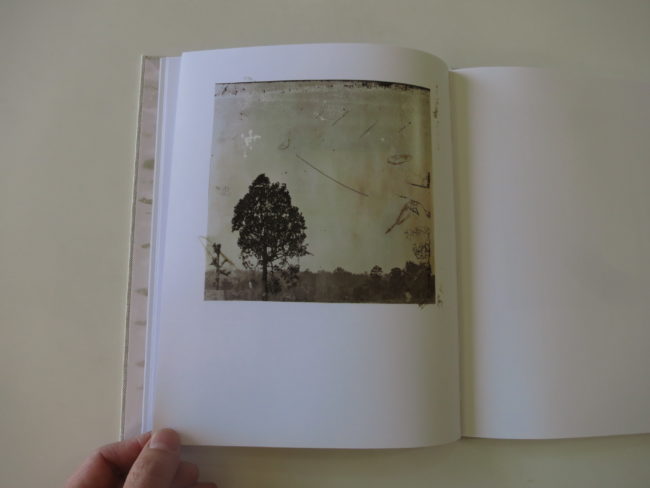

By the second picture, I thought, “Man, this reminds me of those amazing George Barnard pictures I wrote about for APE a few years ago.”

Do you remember? I saw a show at SFMOMA that was meant to feature edgy, contemporary processes that manipulate time, and came away agog at those perfect, magnificent images of Post-Sherman’s-March Atlanta.

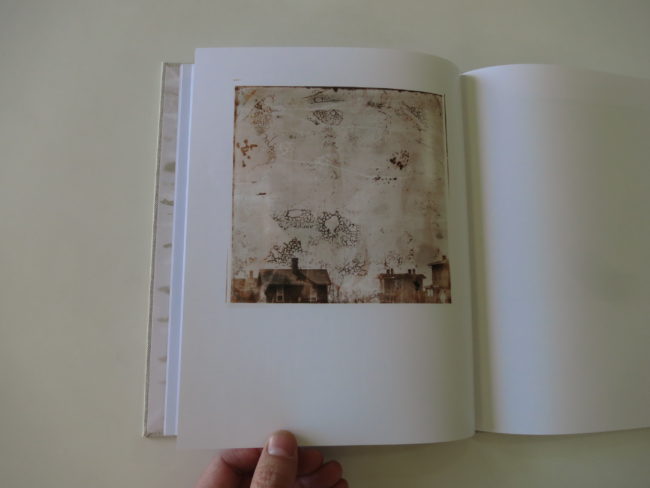

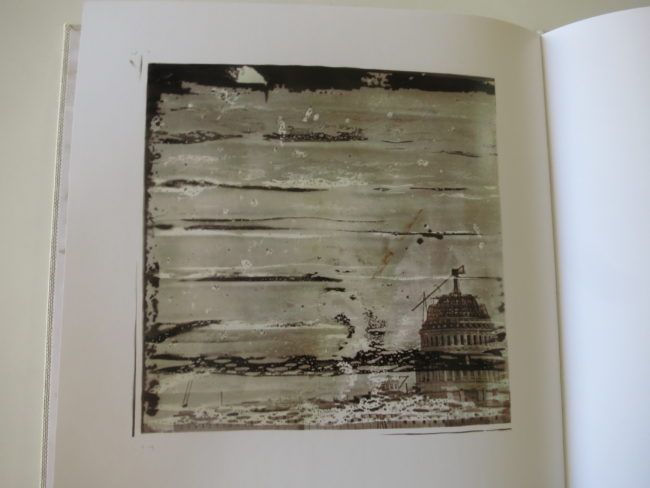

Coincidentally, the essay proved me prescient, as all the images in the book are based on Barnard’s stereoscopic images from Atlanta in 1864. (Well, not all of them, as the last image in the book was made of the Capitol Building under construction.)

Mr. Brandt found Barnard’s images on the Library of Congress website, when he was looking for inspiration for an upcoming show.

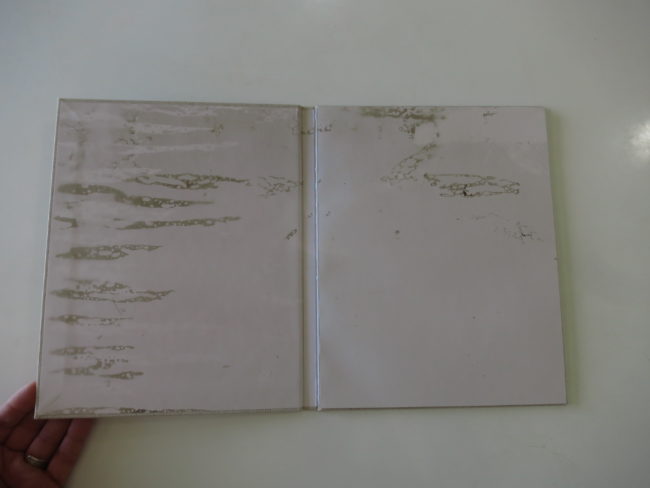

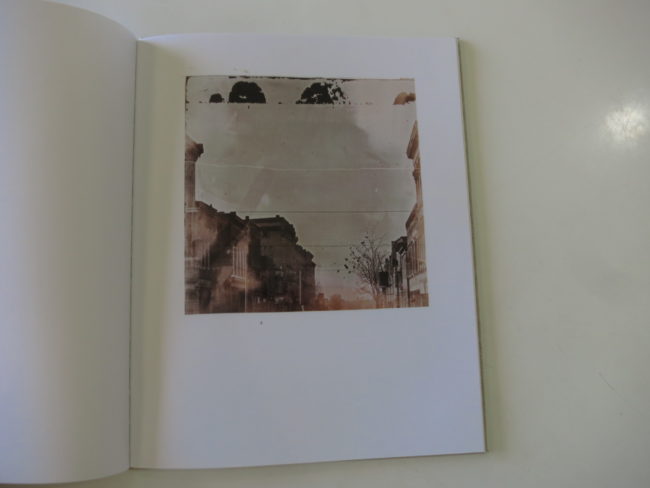

I first became acquainted with Matthew Brandt’s work when a friend curated him into a show at MOPA a few years ago. He’s a part of the California Craft style, where his fellow artists, like Meghann Riepenhoff, use chemical, one-of-a-kind, analog processes to counter our digital realty.

For example, he once used polluted lake water to process his images that were made of those same polluted lakes. Images of a subject often contain the existential materials of it as well.

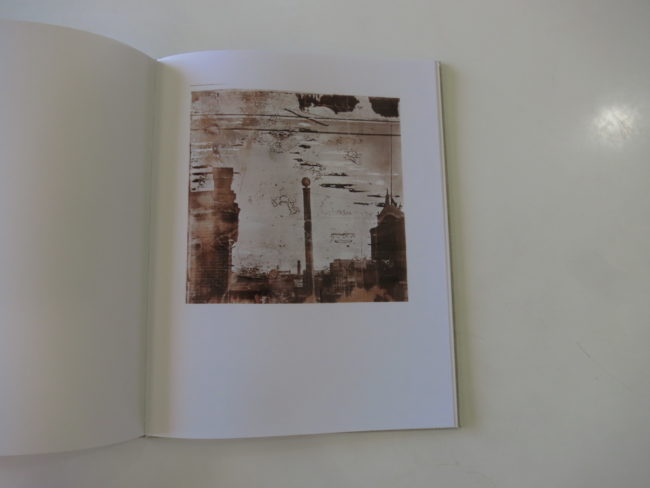

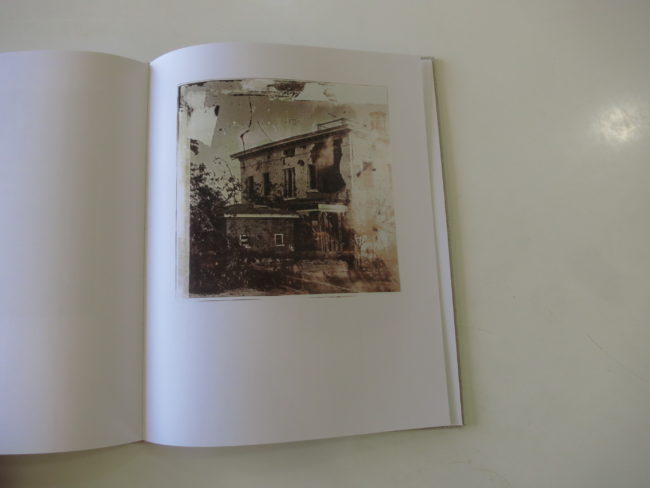

In this case, as Georgia is famous for peaches, he actually included ingredients for peach pie into the chemicals that developed his albumen prints, (which themselves contain egg whites,) and the book claims the resulting tones are due to the confectionary nature of the process.

I’m not sure if he appropriated jpegs, or made photographs of computer screens or actual prints to “take” Barnard’s source material, but the resulting aesthetic is consistent with Mr. Brandt’s previous work.

What do we have, in the end?

They’re textured, and creepy, feeling more ancient than contemporary. But the mashup of temporal eras is real, even if it likely needs textual support to be understood.

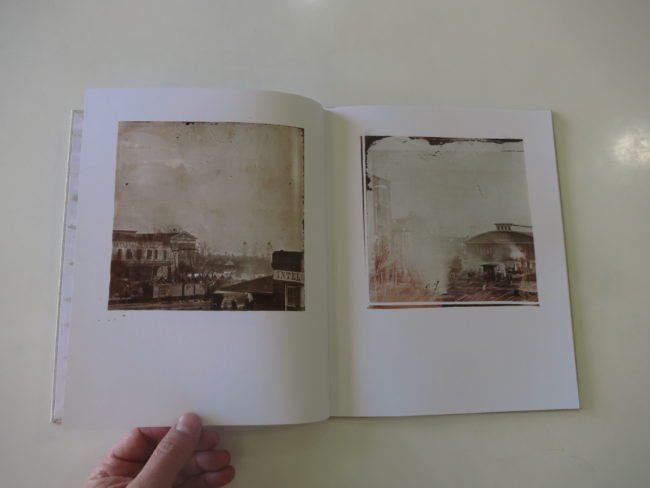

The title of the book, too, hints at the metaphorical images within, as good book design often drops clues in all the right places.

Great art shows us things we haven’t seen before, or helps define a time and place for future generations. While this seems more like a minor project for an important young artist, (to me,) it makes for a cool little book.

And a perfect one to codify today’s musings:

You all, our audience, are high-ranking members of the creative class. You offer jobs, and build organizations. You take pictures to move the needle on public opinion.

So today, with a book that shows the scars of a still-divided country, I leave you with this thought.

How can we all transcend our borders, get out of our lanes, and learn things from people who grew up in different worlds, with different knowledge?

How can you help make things better?

Bottom Line: A cool, smart, Georgia Peach of a photobook

3 Comments

I appreciate your efforts to connect across differences, and observations of how people cluster along similarities. We need to find more connections to erode the divisions in our society. I’m perplexed. Here at this great photo event, you describe people clustering along the expectable, banal connections of share geography rather than photographic interest. This speaks too much of how we value relationships with others.

A tech event I used to attend tried to make such shared interests more visible by marking attendee badges with icons showing activities and interests. They only did this the one year, so it seems it wasn’t successfull.

A sadly amusing annecdote about human clustering. There’s a story regarding lunch clustering for the TV show of years ago Babylon 5. The characters were largely human and 3 major sentient species (the Minbari, Centauri, and Narn) along with handfuls of other species. One of the producers observed that all the actors desssed like Narn would sit together, all the Minbari, all the Centauri, as well. The “others” would clump together. The humans would spread out and sit with friends across “species boundaries”. This was true even when actors would play different species on different days. The human drive to cluster with those “like us” in is strong. But how we judge who is like us is sadly limited.

Thanks for your observations and for bringing interesting books to attention. Both are very helpful.

As a non White who has never been chosen for the NY Times Portfolio Review, it is particularly heartening to hear that there was such a multitude of diversity represented there. I still remember when photographers of color had to join certain organizations to be seen anywhere, En Foco and The Black Photographers Annual were two most notable results. Diversity in the arts does not come easy, and to think that this signals that all is well would be a sorry conclusion indeed (and I’m not saying you do).

Most people of color, myself included. cannot afford the pay for play photo reviews and festivals- and from my understanding they continue to be far less diversified affairs (although I’m hopefully now wrong). It’s no great wonder that such a long overdue first step would result in this voluntary segregation, it flat out exemplifies just how rare a situation they found themselves in…

Hey Stan, I understand this is a natural human impulse, sticking with our own, and hope I categorized it as such. I agree that this event is rare, and can absolutely be seen as a first step for many. But I’ve been there a few times now, and have observed it before. This was just the first time I tried to tackle the issue head on. My main premise is that once we’ve gotten that far down the line, with such a diverse room, perhaps it takes just a touch more organizational effort to ensure that the real benefits of learning from others can take root.

Comments are closed for this article!