They’ve had no rain up in Washington, which you’ve probably heard. Even less snow last Winter. I just saw a headline in the NYT that the Sierra snowpack is at its lowest level in 500 years.

That’s about when Cortes conquered Mexico. The last time there was this little snow, Italians had never eaten a tomato. (Crazy times, this Climate Change.)

Though Seattle is famously pastoral, I recently dined with some friends who live there, and they still flee the city on Summer weekends. They head to “real” nature for the peace and quiet, and will go to great lengths to get there.

Apparently, Josh, Katie and the kids wait 2 hours in a queue to get their car on a ferry. They ride the boat, and 2 more hours to disembark, all before they drive to their preferred camping locale. (5 hours in total, each way.) That’s how badly some people want to escape the urban jungle, and this in a beautiful city surrounded by water and mountains.

This need to be elsewhere is as strong as it is strange. Why can’t people enjoy what they have? Because baking concrete and ceaseless noise will mess with your brain.

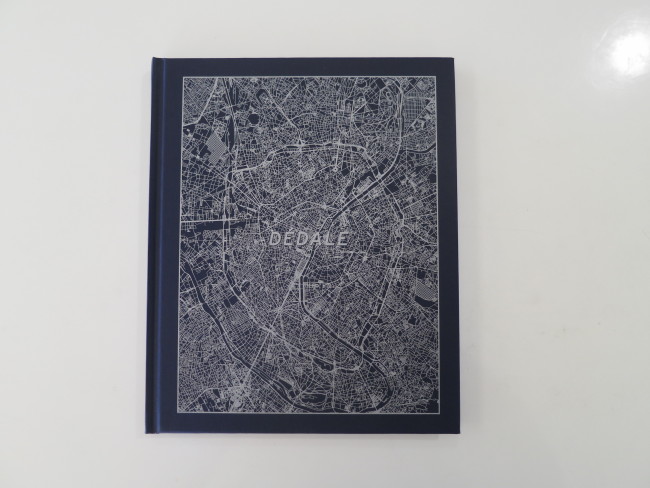

Yes, today I’m wondering about the relationship between cities and their immediate environs, after looking at Laurent Chardon’s new book “Dédale,” recently published by Poursuite.

The banlieues, or suburbs, that surround Paris have been in the news quite a bit, of late. They’re getting a lot of publicity as hotbeds of Islamic unrest and Anti-Semitism, but also for the riots that seem to happen every couple of years. (Burning cars, that sort of thing.)

Why has it been thus? Because those neighborhoods are apparently ghettos for the immigrants, and people of color, that La France has been slow to adopt. (Much less embrace.) As we’ve learned in America, segregating poverty does not make it disappear. Averting your gaze affects your gaze, but not what you choose to ignore.

I’m no expert on the banlieues, as I haven’t been to Paris in 15 years, and even then, it was only for a night. What I know of the situation comes from what I’ve read, mostly. And now, from what I’ve seen.

This book, like some of my favorites, doesn’t give you anything. You have to sort it out for yourself, and even then, supposition is required. (That’s my way of saying the following sentiments may be incorrect, relative to the artist’s intentions.)

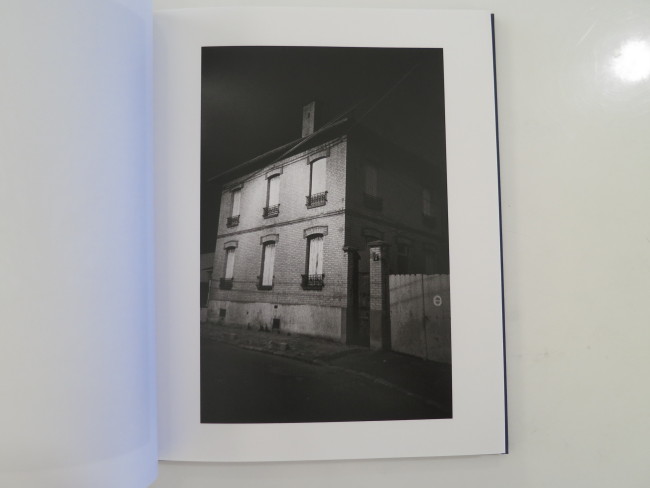

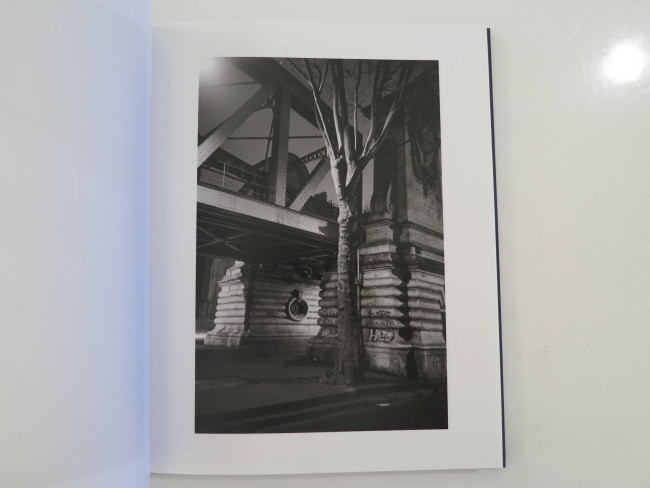

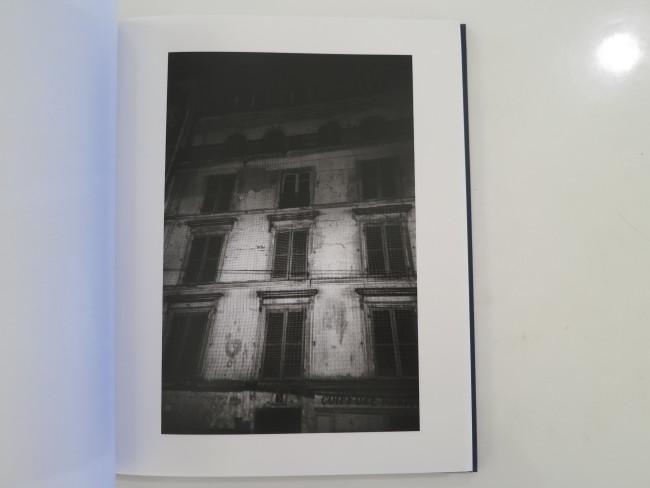

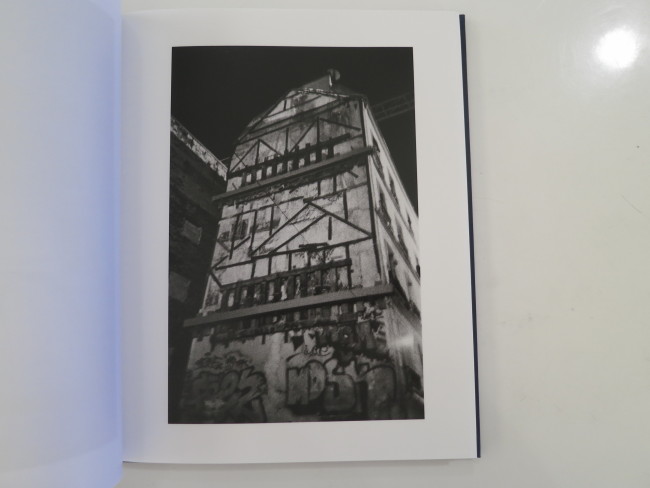

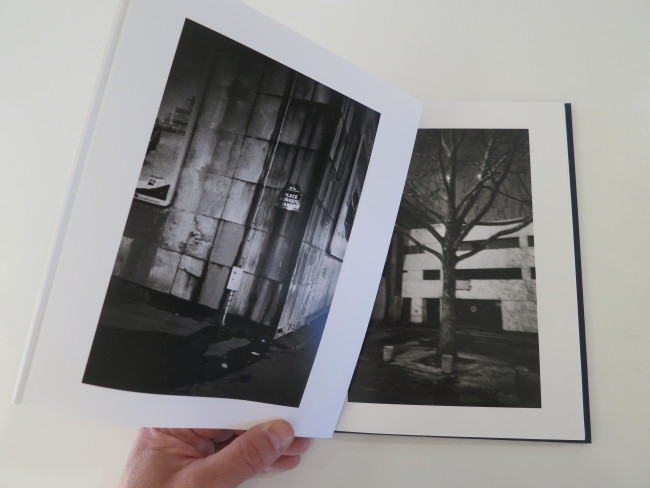

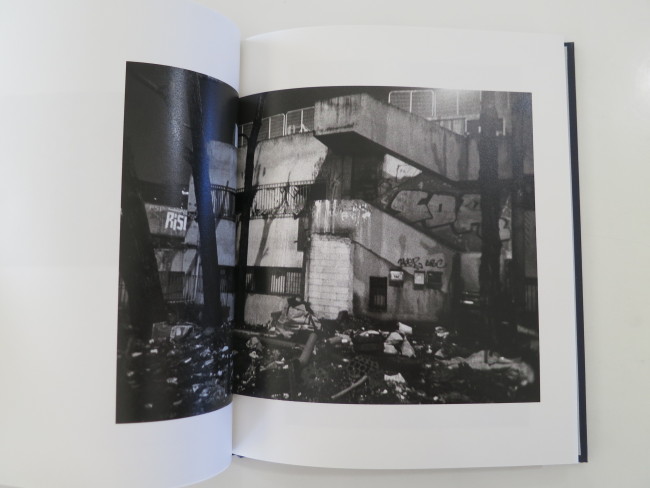

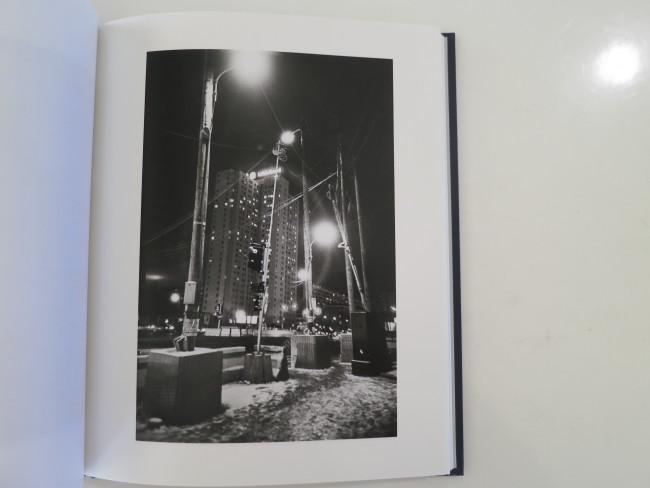

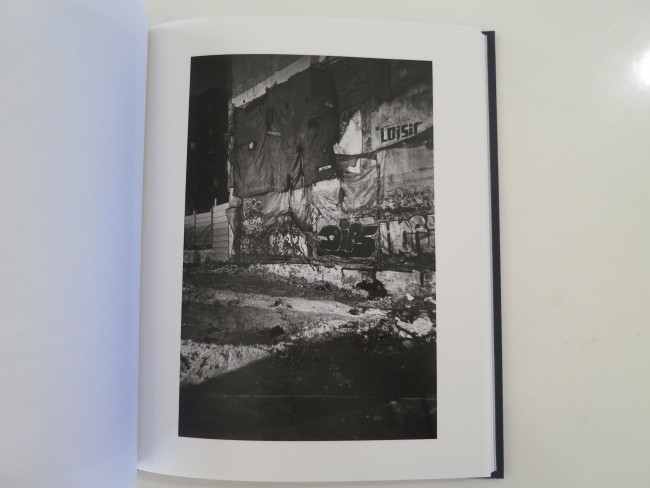

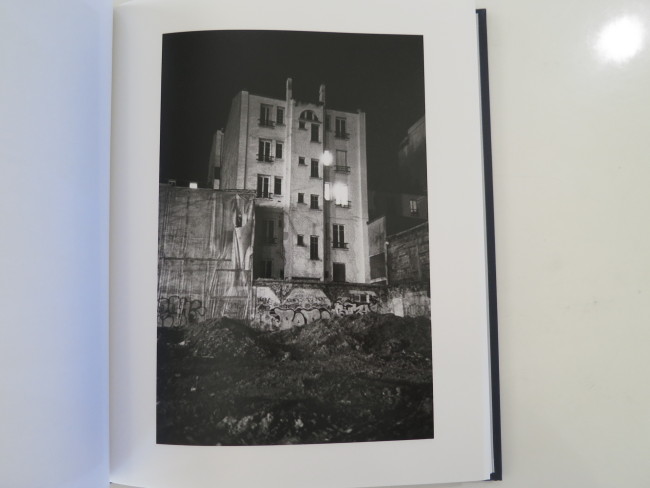

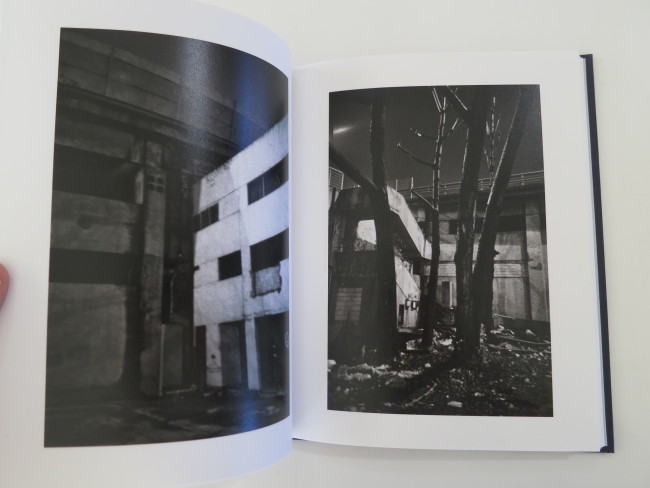

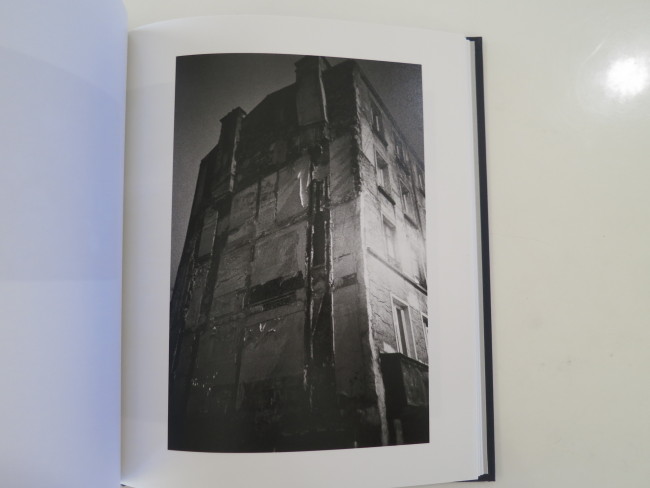

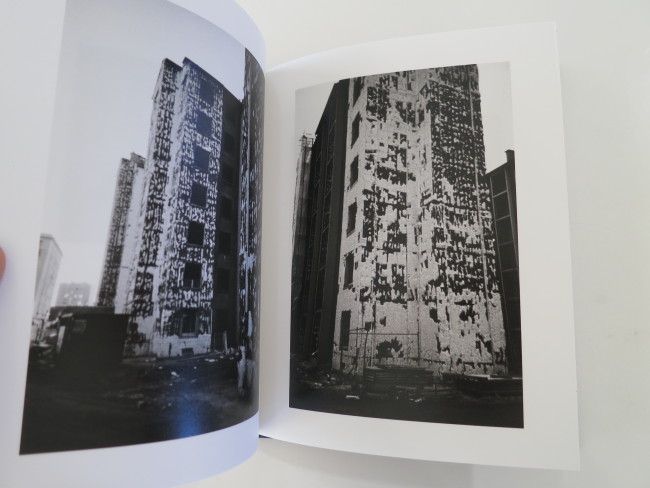

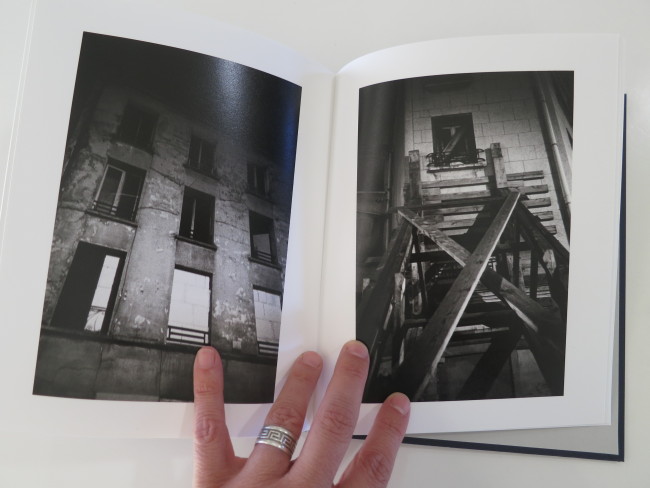

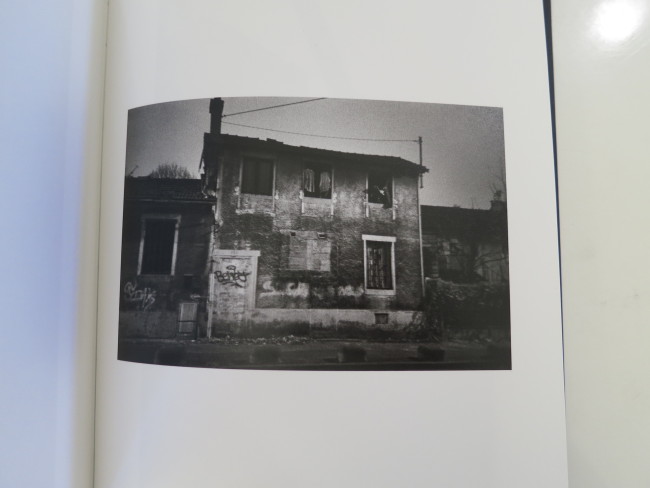

Open it up, and save for the title, all we get are photos. Bleak, graffiti-covered industrial and abandoned structures. Mostly at night. These are to Brassaï’s glowing, Romantic night time Parisian pictures as Johnny Manziel is to Tom Brady.

The cover gives us a map of a Metropolis, and the architecture and few bits of language in the initial photos allow me to guess we’re in the Paris orbit. (Which the end notes confirm.) The stark landscape makes me believe we’re on the outskirts, where the poverty lives. (No gleaming Gothic cathedrals in this one…)

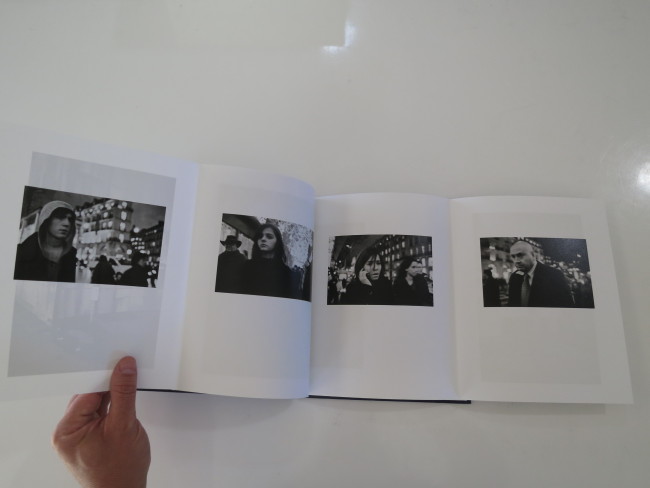

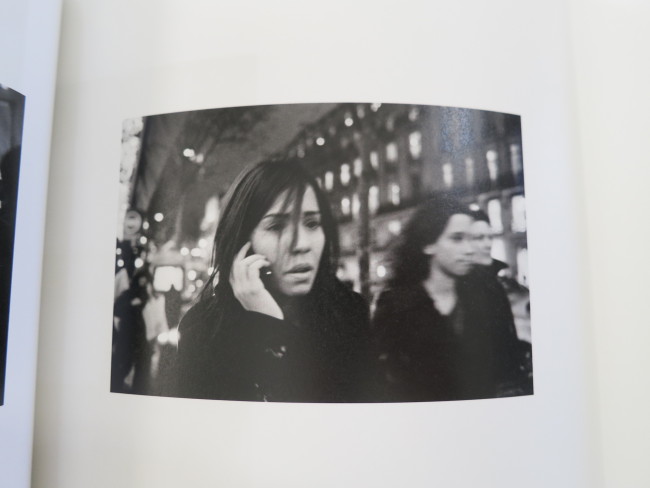

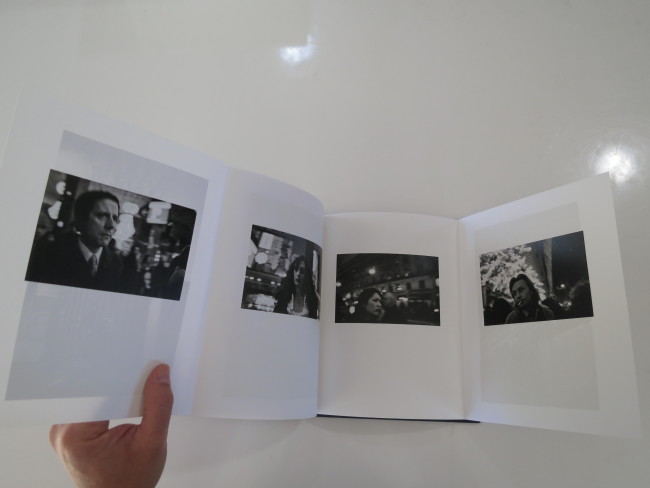

Then, surprisingly, I notice that a page feels thicker than the others. I play around a bit and open it up, finding two double spreads of portraits. Grabbed photos of pedestrians at night, lit up by what feels like the glow of the city center.

Then back to the gloom. The process repeats itself three or four more times. Always the same: up close, stolen street portraits, the kind that require copious light and unsuspicious people. You’d never get pictures like this, lurking somewhere unpopulated, shoving your camera in the grill of scared strangers.

To me, it’s a structural metaphor. The shiny center, encircled by a sad, weary infrastructure. The breezy heart of the city, with danger pervading the darkened edges.

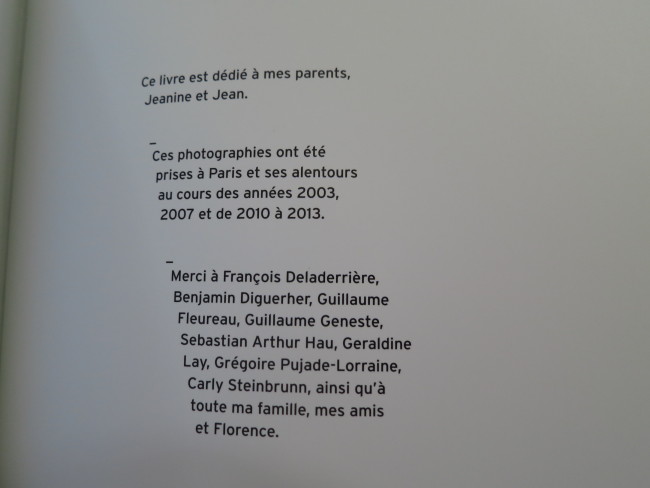

This is just my read, of course, because the book gives nothing away. The end notes, in French, tell us the artist dedicates his book to his parents, and that the pictures were made in Paris and its surroundings, in 2003, 07, and 2010-13.

That’s it.

The use of black and white is perfect here. Not only does it reference Brassaï, but it gives a genuine menace to these pictures. It makes you wonder how safe Mr. Chardon was, while he snapped away.

They make the outskirts look bad, but not the banlieue residents, as there are none to be seen in the lightless places. So we begin to wonder: who would prosper in an environment so ugly and decrepit? How can people be expected to succeed, on the fringes of Paris, when their world is as bleak as Paris is beautiful?

I genuinely don’t know. Do you?

PS: This column has gone on for so long that when I tried to save my document as “Chardon,” I learned the title was taken. Apparently, I reviewed another of his books back in 2013. Not sure what that says about my memory, but I’ll have to re-read it, to see what I thought of his previous effort.

Bottom Line: Chilling photos on the outskirts of Paris