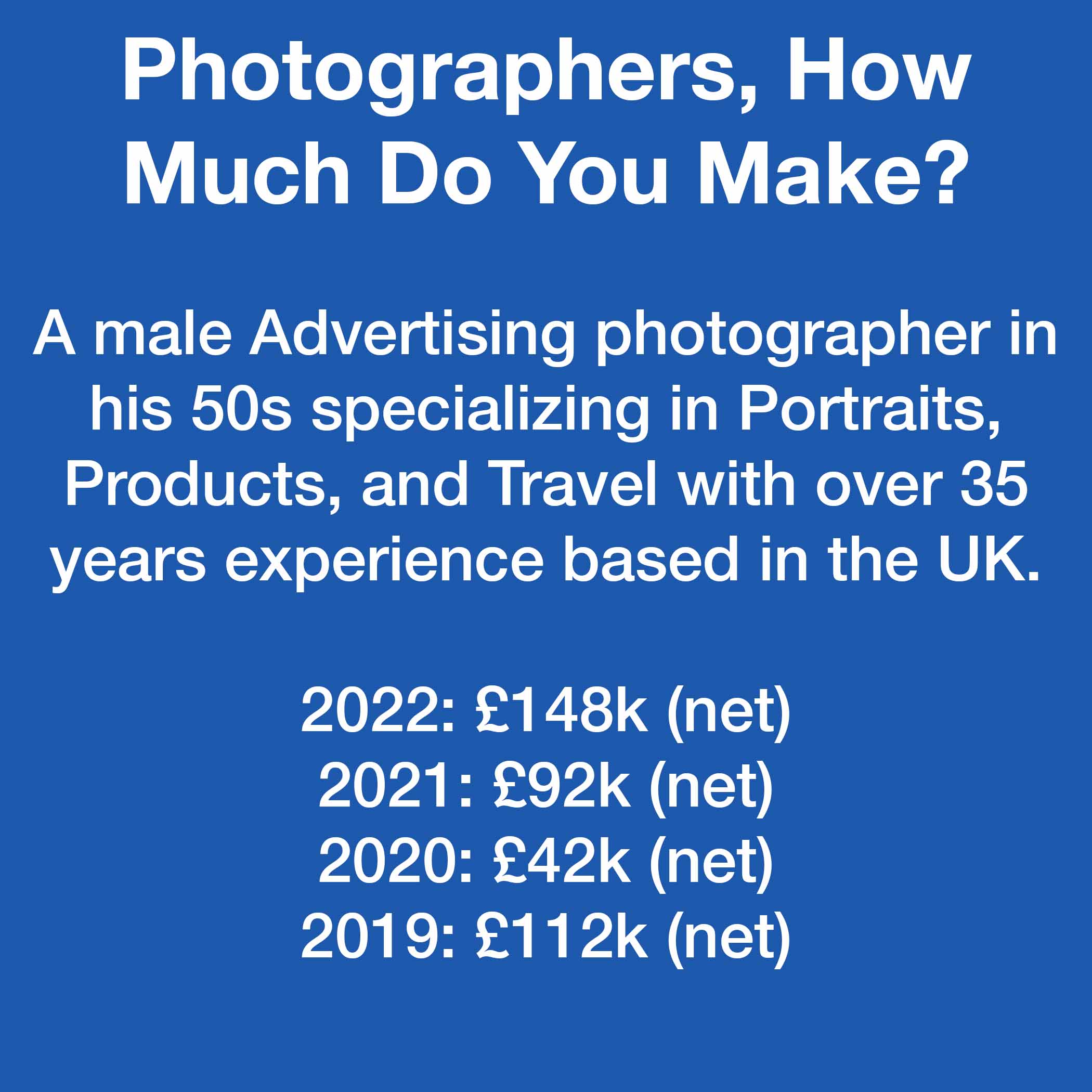

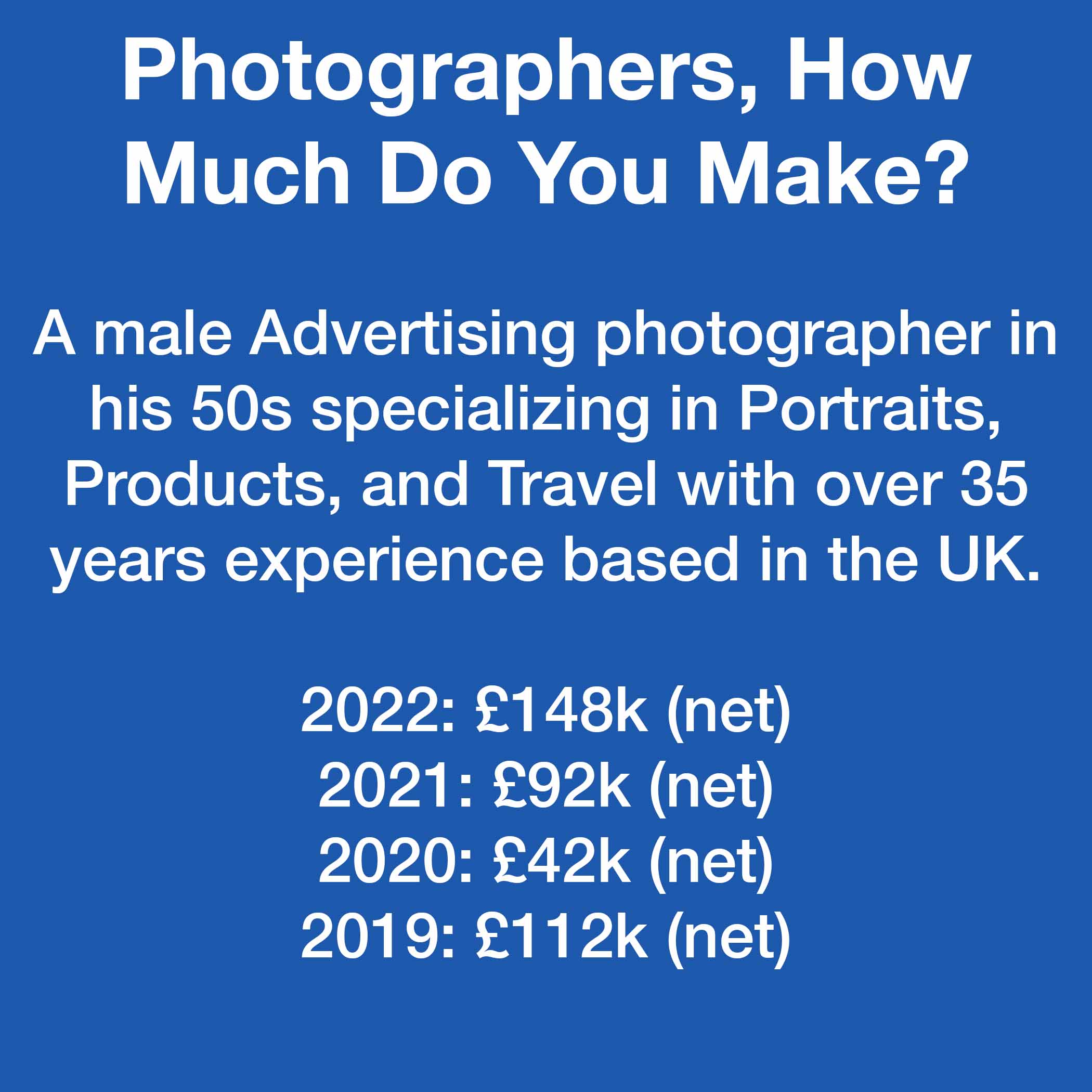

1£ = $1.24

2020 includes grants, Gov’t aid, and paying work.

I get 80% of my earnings from travel photography, with portrait based ads at 15% and product at 5%

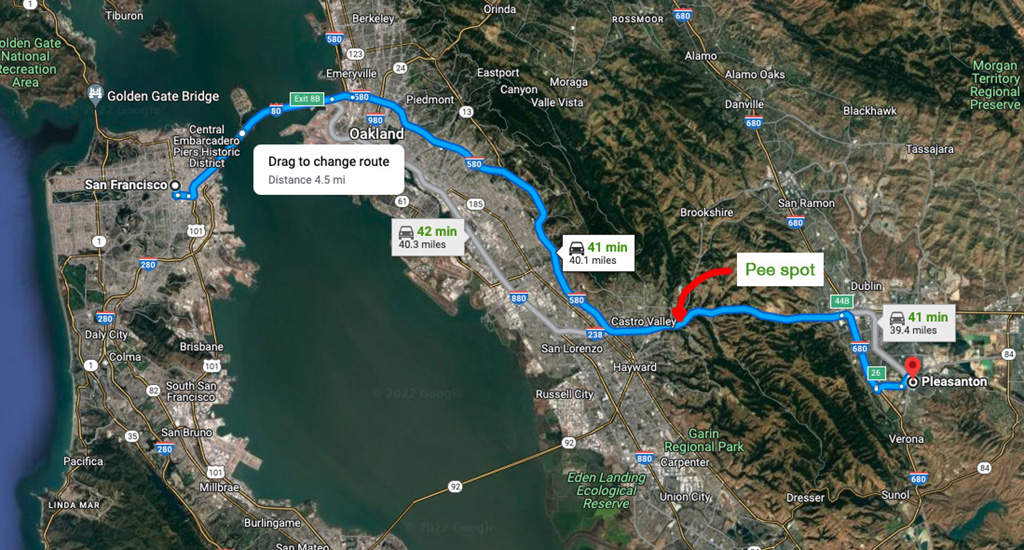

I travel often to the US for work.

I don’t have a rep. A good friend who is a superstar fashion photographer said, “Why do you want a rep? What are they going to do for you that you’re not already doing for yourself?”

Most of my clients are mid-ranged national companies and gov’t agencies.

My only overhead is my studio, that I rarely use but creates its own income through rentals. It pays for itself.

My profit margin ranges from 40-60% depending on the year(new Mac, new camera system etc.).

2019 I worked 49 days. In 2020 I worked 12 days, 2021 I worked 42 days and in 2022, I worked 38 days

At this point in my career, my clients finally understand usage and the value of good photography. Over the past 16 years, I have honed my business to a “charge more, work less” motto. My market is quickly filling with foreign clients who are understanding of usage and licensing, so negotiating goes quickly, and we spend most of our time being creative with the projects. I do service my clients pretty well, though; if they call/email/text at any hour, and if it’s feasible, I’ll get them what they need. I have never been abused by this offer, and most clients like the fact that it’s there even if they don’t take advantage of it. My clients range from small business owners(who I love to help out and make the most of their products/services) to big gov’t agencies who know I will come through on budget and on time. With my “charge more, work less” motto and my licensing agreements, life is great. I enjoy working with people now. Previously, ten years ago or so, I dreaded working with new clients and trying to educate them about licensing. Now 90% of my clients are fine with usage, and the other 10%( usually local biz), I just leave them with an in-perpetuity license (no 3rd party usage) agreement, and they’re fine with that.

My normal shoot would start around 8-9 am and go to 5 pm. There would be an hour of editing and uploading to a client gallery on Photoshelter. Once they choose their images, there might be another 2-3 hours of grading and simple retouching. Any heavy retouching is sent to one of my outside retouchers.

Licensing is usually 2 years for one media or one year for 2 media, that’s included in my fee. As I’ve said though, most of my clients are now well educated in it, so they know that the images are usually only good for a few months before they should refresh them; so most go for the one year/2 media plan.

Larger clients will come back to me to negotiate for other regions, and that is where I make some real bread-and-butter revenue.

I worked on a project with an EU client for 18 shooting days. I was paid €2000/day for 10 selects from each day, with simple retouching. The usage fees were €20000 for the selects with no 3rd party sales/use. I took home every cent of it since they covered all the travel and expenses, so net €56000 for 18 days.

I work locally with an entrepreneur who is always starting a new business. I like the guy, “He’s a good egg,” so I give him a lot for a little. I offer him portrait-based ads for his start-up at €350 per ad with in-perpetuity licensing for the immediate region.

I had a client who first introduced themselves as a renowned charity looking to cover off case studies. I wanted to give back, so I agreed to her terms and rates.€150 per location/case. I was fine with it; it took me an hour to shoot and an hour in post. It wasn’t until I was in with them for a year before I found out they were another vendor for the charity and were using the charity name to get discounts on other work. I told them I need to be compensated from this point forward, and, well, I’ve never heard from them again; maybe karma will catch up with them.

My video work is about 20% of my business.

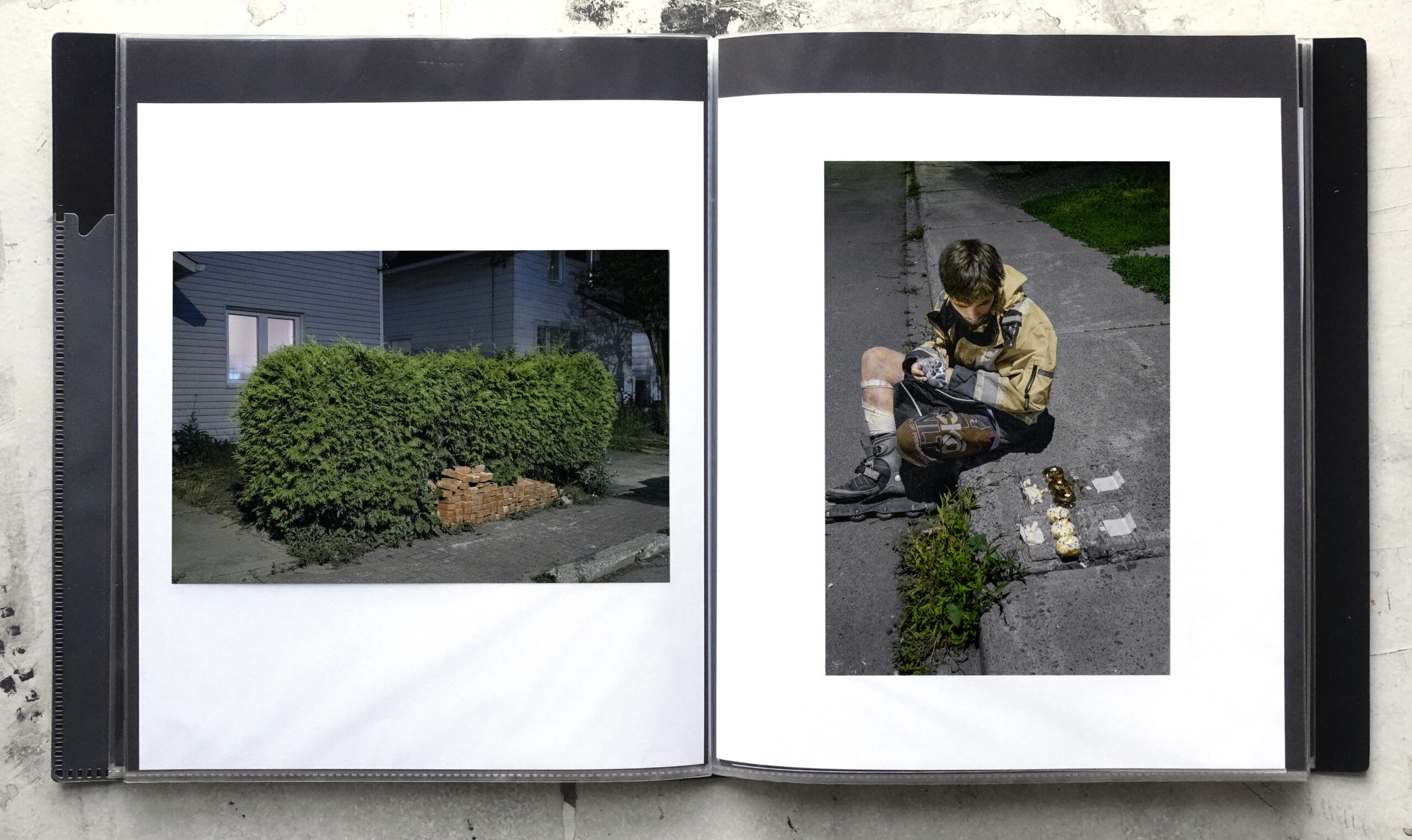

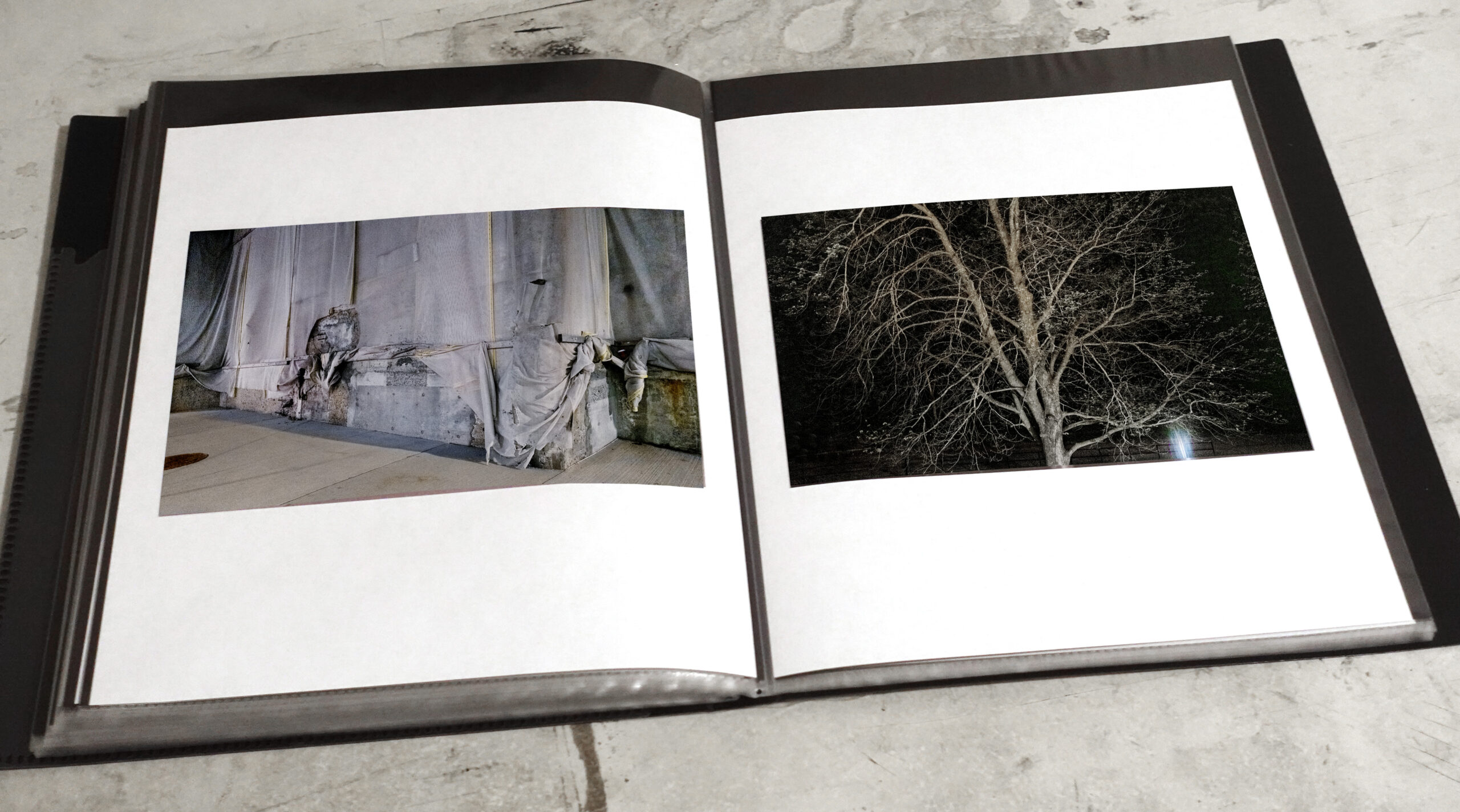

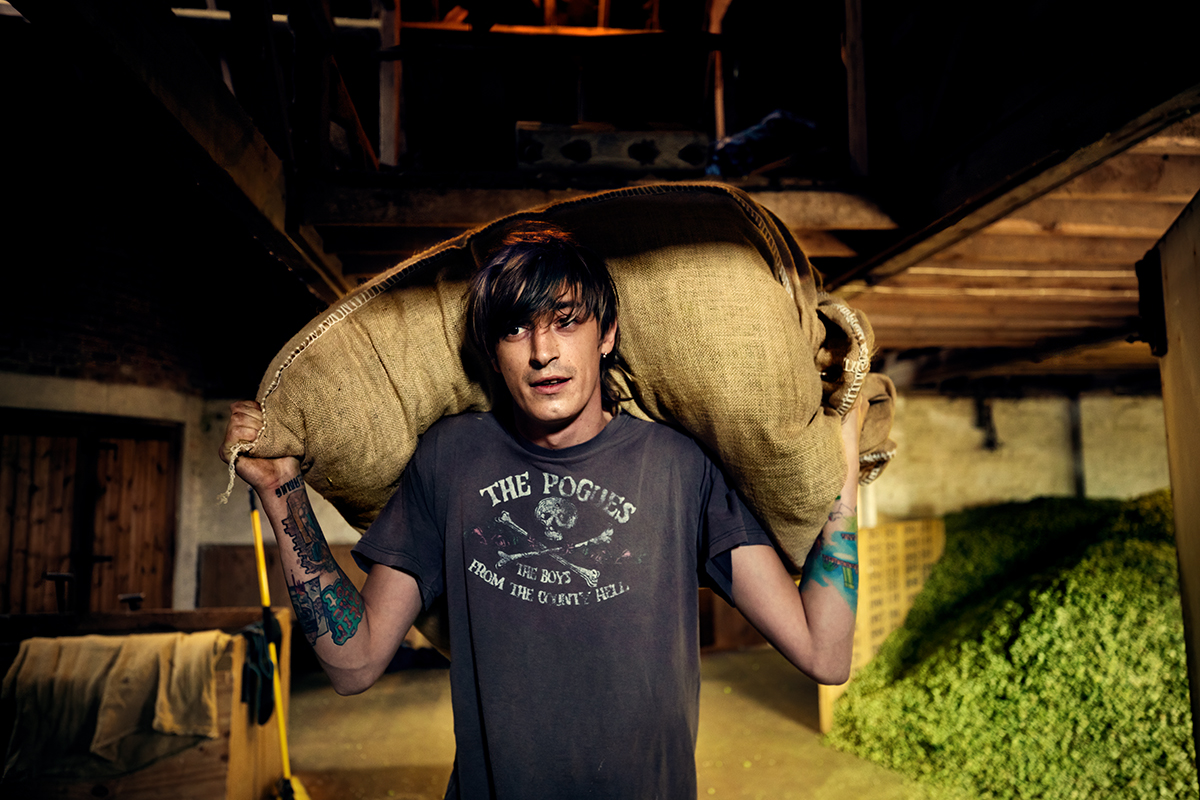

The best advice I received is never ever show anything but your very best work, the stuff you would hang on your wall. So many times, I see others posting work of their’s, that doesn’t reflect themselves at all or is just plain bad. I tell students and up-and-comers the same.

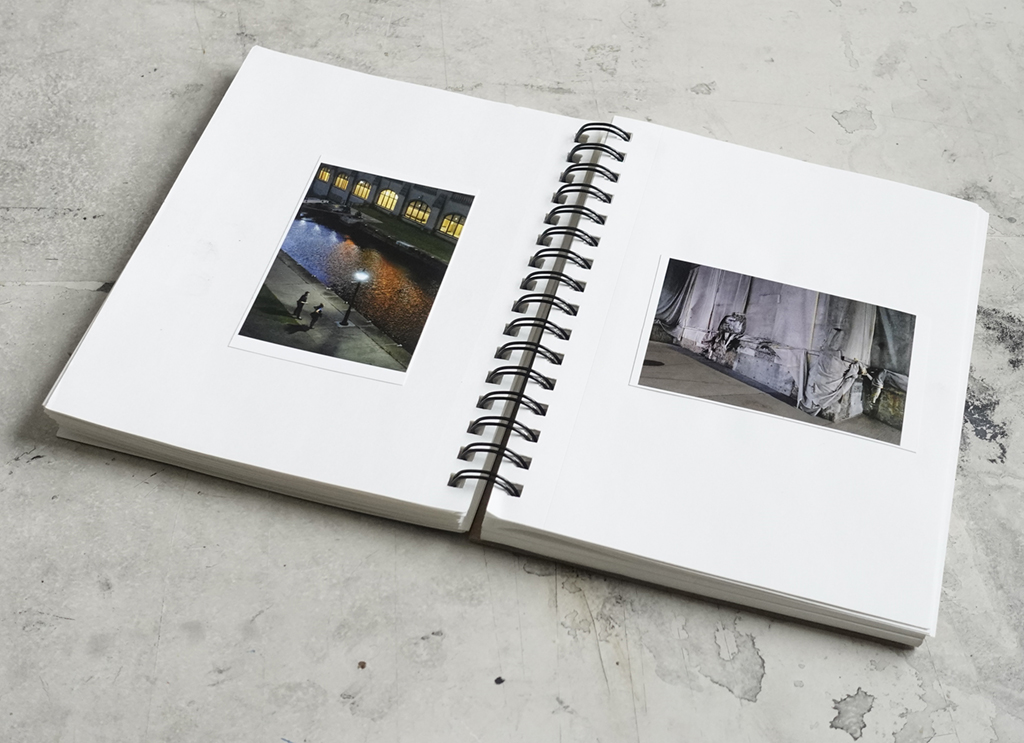

I don’t do any marketing outside of my website. I do make meetings to show potentials my printed portfolio. Nobody can sell you like yourself and your images. Each image has a story, and the potentials love to hear them. I also make a point of asking them before I leave if you liked my work and do you know a couple of other friends/companies who might benefit from my work.

I’m socking away money in retirement savings, investing in the stocks every month. My overhead is soooper low, so I almost always know my margins on any project. At the end of the month, whatever is left, I put aside a portion for taxes and some for investments.

Share your knowledge with others around you, invite your colleagues and competition out for lunch/coffee/drinks. A better-informed market is good for all. Ease new clients into licensing images; tell them the benefits of renewing images every 6-12 months etc.

And “charge more, work less.”

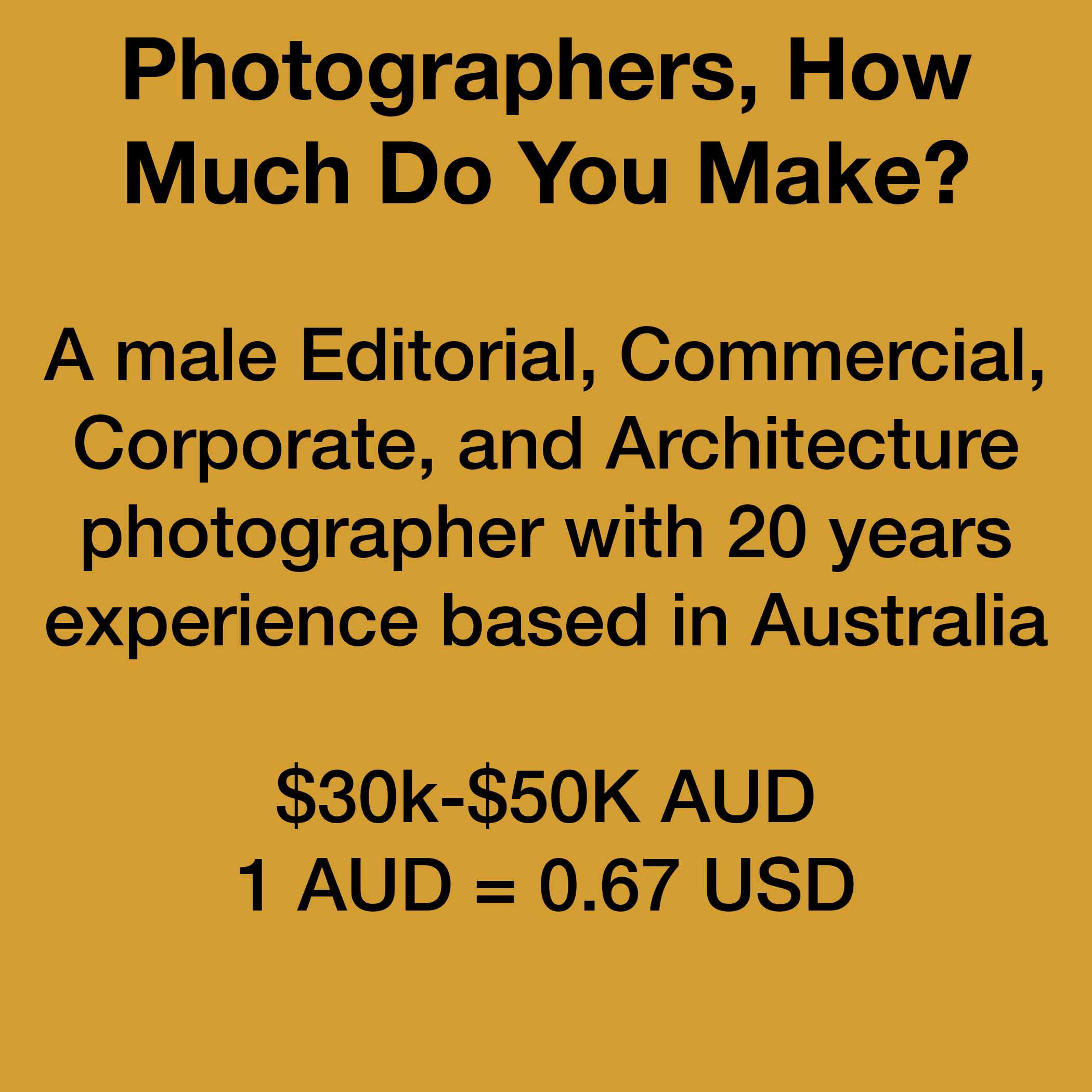

My business is set up as a Trust, so my trust also pays a wage to me as its trustee, which is an additional $50,000AUD per year.

40% Large advertising clients (Top largest companies in Aus) – most briefs have people, kids, and families as focus.

40% Large fashion retail, commercial clients- mainly captured in studio (more detailed than e commence but used to support online content.

10% Social/influencer work.

10% teaching/mentoring online to other photographers in the industry.

During Covid, due to very strict lockdown rules in Australia, I could only make an income from shoots I could facilitate on my own in my own home, reuse of past shoots licensing, and mentoring online.

Mostly work with the largest companies in Australia. Our economy is not on the same scale as Fortune 500 due to the much smaller population/economy.

Very minimal overheads. I don’t have my own studio or any of my own gear. My main expenses are hiring equipment for shoots, assistants/digital operators, and retouching. I prefer to outsource the retouching to give me more work/life balance. My profit margins would significantly increase if I owned all my own gear however, I am required to travel interstate very often for shoots, and Australia is a very large country to travel in. I find it physically challenging to transport heavy equipment around, to and from an airport on my own.

My profit margin is approx 50%. Last year my photography income, supplemented with teaching and influencer work, was approx 300K, and after expenses was $180K.

My agent adds an agency fee to all my jobs, plus they make money on the production of my shoots.

I work approx 80-100 days a year.

My clients are very loyal. I have a handful of clients who have been with me for over 10 years. They used to shoot 3-4 times a year, and now they are shooting up to 10-12 times per year. Due to the industry being very small in Australia (but equally competitive), I have found it extremely important to maintain relationships regularly. I’ve never very been a photographer who would ‘wine and dine’ with creatives or attend any agency parties. I work very hard on keeping in touch by scheduling one on one catch up’s with art directors and producers. I also make a point to continuously shoot new personal work and promote this beyond just my agent’s promo/advertising.

My income has changed quite a lot in the last few years. I am considered a fairly ‘young’ photographer in the industry. I feel like the last couple of years have seen me grow as a person, businesswoman and artist. I feel the economy here in Australia has been given a boost post covid which has also helped me. Covid was an extremely difficult time due to the strictest lockdowns in the world. Where I live, we were not allowed to travel further than 5km away from our house for well over 12 months in total between 2020 and 2021. Almost all shoots stopped (apart from some in Queensland – out of our industry moved north in this time). I had to become very savvy to survive during that time.

The cost of living has become astronomical in Australia. I am very lucky I have minimal overheads and own my home, so I haven’t felt to pinch as much as others.

During covid, I started offering one on one mentoring to other photographers. My main type of buyer/student is usually someone (usually Australian) who has an existing photography business but wants to move away from weddings/portraits and into the commercial industry. I also mentor photographers who are already in the commercial industry but feel a bit stuck- most of these students are from overseas (US, Sweden, UK, NZ).

I also make money from some small influencer jobs – I create images using my family and home to create online content for brands. I only align myself with brands that fit the overall aesthetic of my commercial work.

The average shoot is 10 hours. Some are longer some are shorter, depending on the shoot. Mostly my shoots are 1-day shoots and occasionally 2-3 days.

Licensing terms literally change for every shoot. Sometimes I am able to charge 100% of my BUR for loadings, but mostly it ends up being negotiated. Many of my shoots are for Australian territory only, but sometimes they are licensed for the US as well.

Shoot Rate is anywhere between $2.5-5k per day plus loadings.

Best paying shoot this last year is for a top 7 Australian company 1 day for use on 7 stills images- $25K shot on the back of TVC. Licensing period for 1 year.

The worst paying was online catalog work for a very large fast fashion Australian brand but international selling. Paid me $2500 (and they complained about that being expensive). Refused to pay loadings or any pre/post work. They used the images for 1 week only.

I am just starting to shoot video. I would like to expand on this. Have shot with DOP and directed in the past.

My advice would be to keep your overheads as low as possible in the economy and world we live in today. Covid taught me the importance of this as I didn’t feel the impacts finically due to having very minimal expenses. I do daydream about having all the amazing equipment and owning my own shooting space, but in the end, I’d rather have cash in my pocket and minimal debit to see me through the tough times.

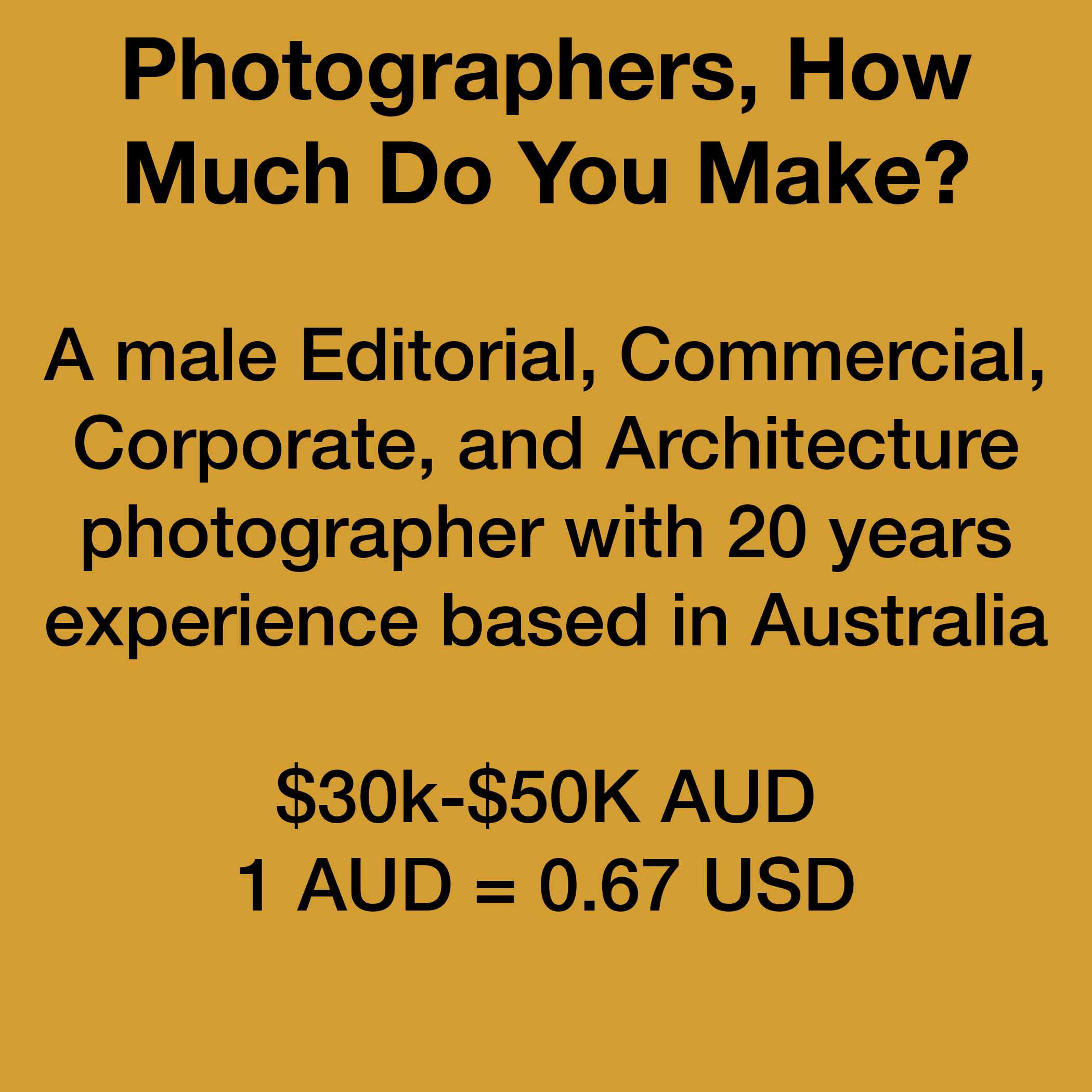

I mostly shoot editorial, and my main clients are national newspapers and magazines, wire services (Australian and international), national corporate clients and medium-sized businesses, associations/business groups, architects, and builders.

My overhead is car repayment $500/month, petrol, insurance and registration $650/month, public liability and equipment insurance $200/month, phone bill $80/month, internet $60/month. I used to have a studio rent assisted at $300/month. Then there’s regular things like rent $500/week average in Australia plus gas, electricity, food, entertainment etc.

I work on photography pretty much every day, but actual commissioned work is about 70-120 days a year (varies).

Freelance editorial rates in Australia have not changed in 20+ years. In the early 2000’s the day rate was $450 + expenses (phone, mileage @.75c/km). Today day rates range from $350-$400 + expenses (which are often questioned and met with push-back from picture editors). Corporate rates have increased about 30% in the last 5-8 years.

I also do occasional teaching, a print sale here and there, larger project commissions on occasion, assisting, and laboring.

There is not one normal day in editorial. Sometimes a job is one portrait that takes 20 mins plus post-production. Other days it is multiple jobs for the same day rate. In the last few years, the two major news outlets for freelancers (News Limited and Fairfax, now 9) have pushed for half-day rates $200/half day. Many of us have rejected this, but there are people who accept it.

With regards to licensing, it is a case-by-case basis, commercial clients seem to accept it but it’s an add-on of 20%-50% or something like that for use in perpetuity.

A shoot for a building client usually involves a site inspection (recce visit), one or two shoot sessions (3-4 hours each), and about 2-3 hours of post. For these jobs, it is usually about $2500 + expenses including licensing.

My best recent job was a corporate shoot over four days at $2500/day + post-production $600/day + travel expenses + licensing in perpetuity (not copyright) for $1500. The days ranged from 8 to 12 hours. A shoot like that every few months goes a long way to propping up the bank account and also maintaining a sense of self-belief and self-worth. I cleared $12,000 for that job.

I do about 4-5 weddings a year and I charge between $4000-$6000 (includes all-day shoot and post-production). Even though these are good earners, I’m not keen to do more than this per year.

My worst recent job was a day for a newspaper at $400 that lasted eight hours with very little travel (stakeout) and no photographs taken.

Less than 5% of my work is video.

The Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) is the national union and workers’ representative body for journalists and photographers in Australia. Their recommended freelance rates are 3x the actual rates paid by most editorial outlets. If any photographer were to charge what is recommended, they would be laughed at.

With a relatively small media landscape, the editorial market in Australia is not a place aspiring photographers should be looking as a viable career option. Multi-skilling and diversity of income is essential.

As well as being the worst payers, editors and picture editors on most newspapers do little to show support for their freelance photographers. Discussions, queries, and rebutting of invoices is common.

There is a definite power imbalance for freelance photographers and employers in Australia, and I can’t be enthusiastic for photographers who want to work in day-to-day editorial journalism world in a freelance capacity. While editorial is often more rewarding (working on stories with real people in situ and having more agency over the photography), I believe photographers must learn to use their documentary skills (including personal skills) in corporate and commercial environments to make a decent income.

A message to everyone: Never accept half-day rates in editorial!

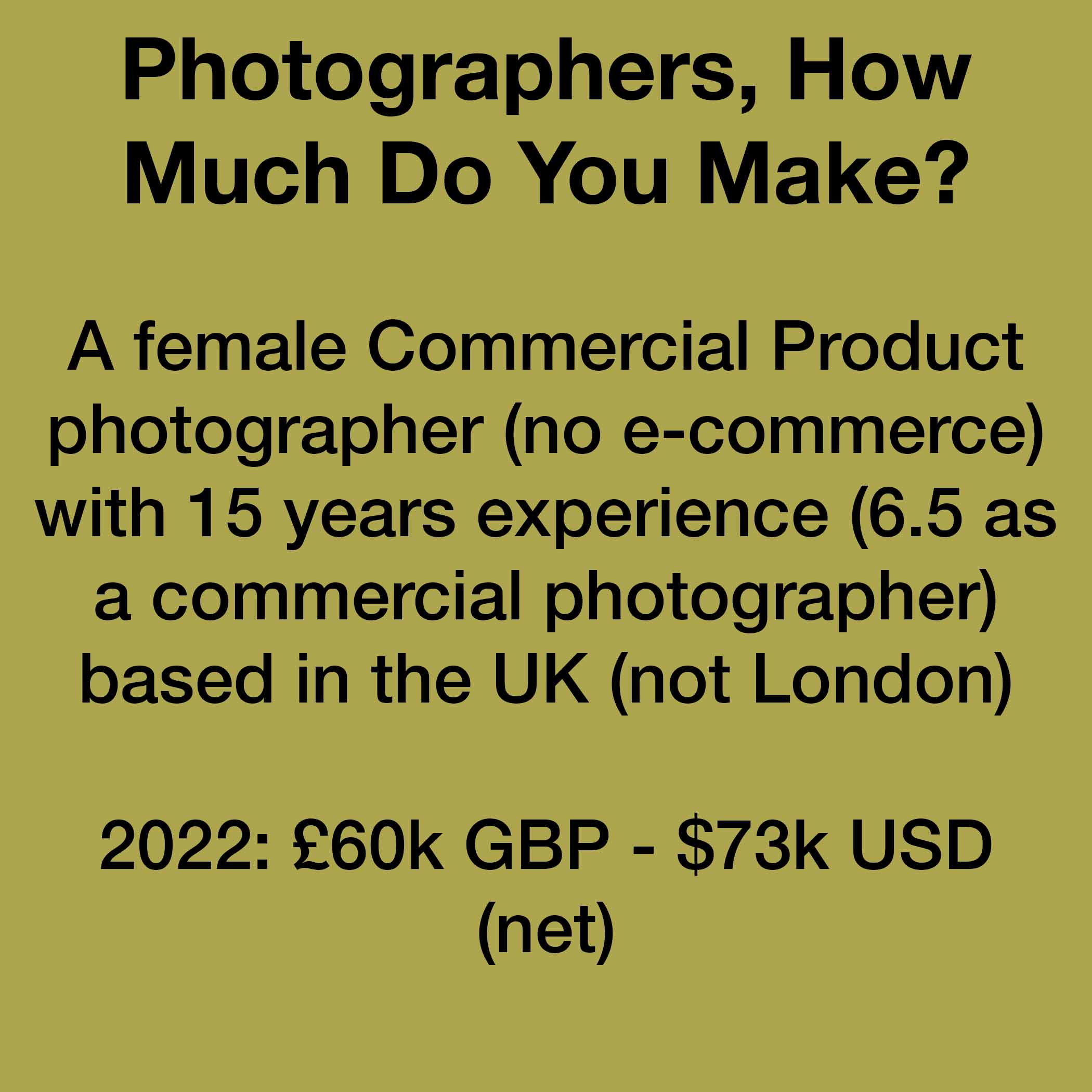

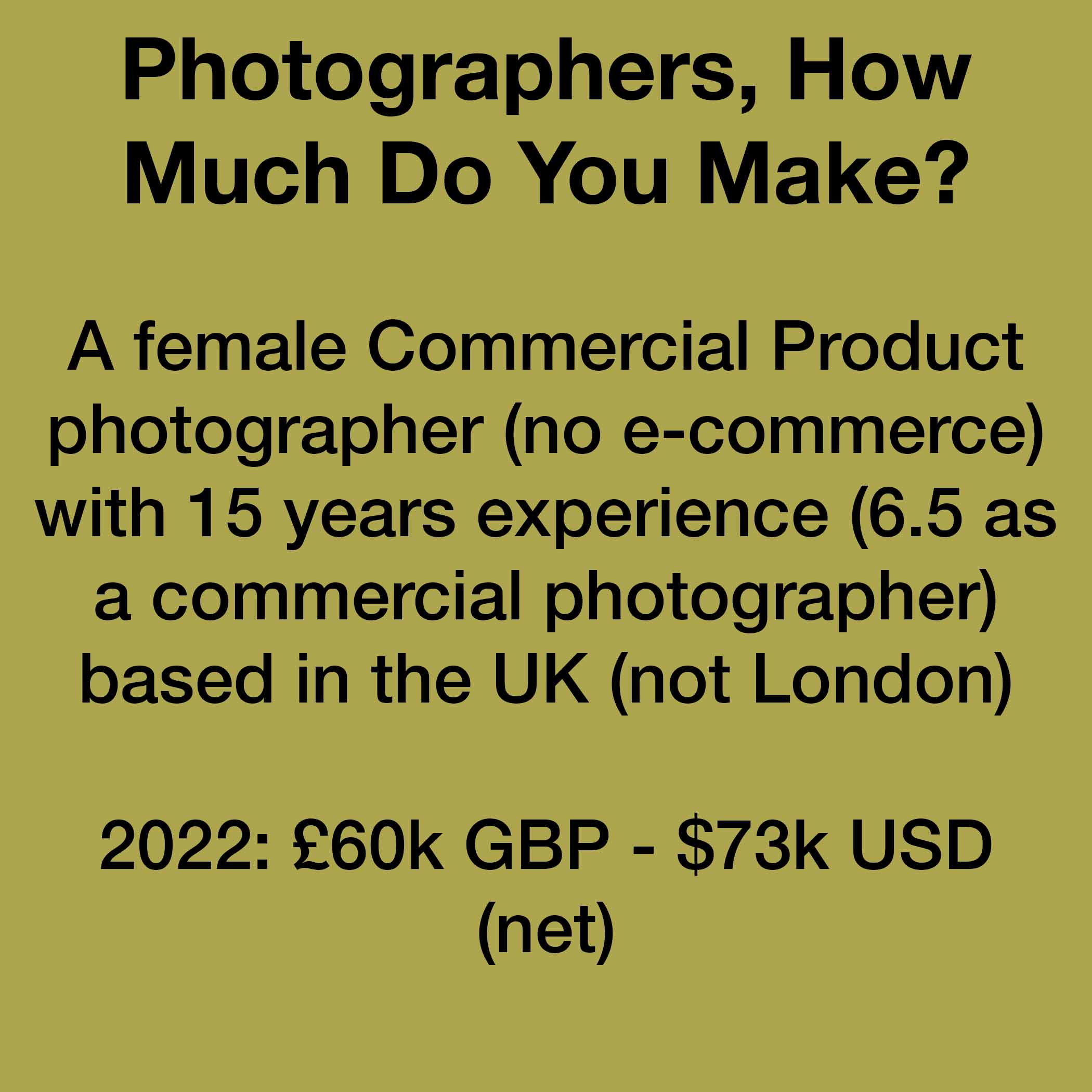

I mostly shoot advertising images and creative content images for social media and websites.

My clients are mid-sized companies based in the UK, US, Europe, and Australia that are in the cosmetics, skincare, and health product space; although I also shoot other types of products, but they are more ad hoc.

No employees since the pandemic.

I work from a home studio, so my overheads are fairly light. I was about the move to a studio space before the pandemic, but very glad I didn’t, as it probably saved me a lot of headaches.

In the UK, we have a VAT (value-added tax, which is currently 20%) threshold of £85k GBP/$102k USD. Before moving into commercial photography, I used to do wedding photography and was VAT registered. When I started doing product photography, I de-registered from VAT, and I intentionally wanted to stay below the threshold because I found it quite stressful, so I now turn over around £80k GBP/$96k USD per year. My gross profit is around £70k GBP/$84k USD, and my net profit is £60k GBP/$73k USD. As a sole trader, I consider this a fairly good wage for the area that I live in.

Hard to calculate days worked per year but around 230, I’d guess. I tend to take a couple of weeks off around Christmas and New Years and a couple of weeks in the summer, plus random days here and there. I book two shoots per week, and on the other days, I do all the other jobs such as admin, pre and post-production, marketing, etc. I try not to work at weekends.

My turnover dipped by £10k in the first pandemic year but picked up again after.

I also do art direction and styling, and depending on the client and the brief, I can charge more for these services. Probably 60% of my clients also want art direction.

An average shoot is roughly for around 15 images depending on the brief, with at least one pre-production day, one shoot day, and probably half a post-production day. The average fee would be around £2000 GBP/$2400 USD. I include 2 year’s license for digital mediums in the initial fee. Print and OOH etc., are separate licenses. Gross profit from the base rate is usually roughly around £1700.

My best recent shoot was with a US-based client in the health supplement space. Two separate shoot days, one with a model. 1-2 days of pre-production, 1-day post-production. Full art direction and styling. Total initial fee with a 2-year digital license was £7000 GBP / $8400 USD, with a gross profit of £6300 GBP / $ 7600 USD. Further licensing for OOH £3000 GBP / $3600 USD.

My lowest paying recent shoot was an EU-based tiny start-up company with a new shampoo. I like to sometimes book very small shoots for brands that I think have potential in the hopes that if they become successful, they will continue to work with me on bigger projects. 4 images with a 2-year digital license, £500 GBP / $600 USD. Couple of hours of pre-production, 2 hours of shooting, and no costs as all props were from my own collection.

I don’t shoot video, but I do create stop-motion animations, and I’d like to do more of this. Currently, only around 15% of my income.

It’s not always about forever growing and making more and more. I have a happier, more balanced life since I decided to stay below the VAT threshold and be satisfied with the pretty steady income I make.

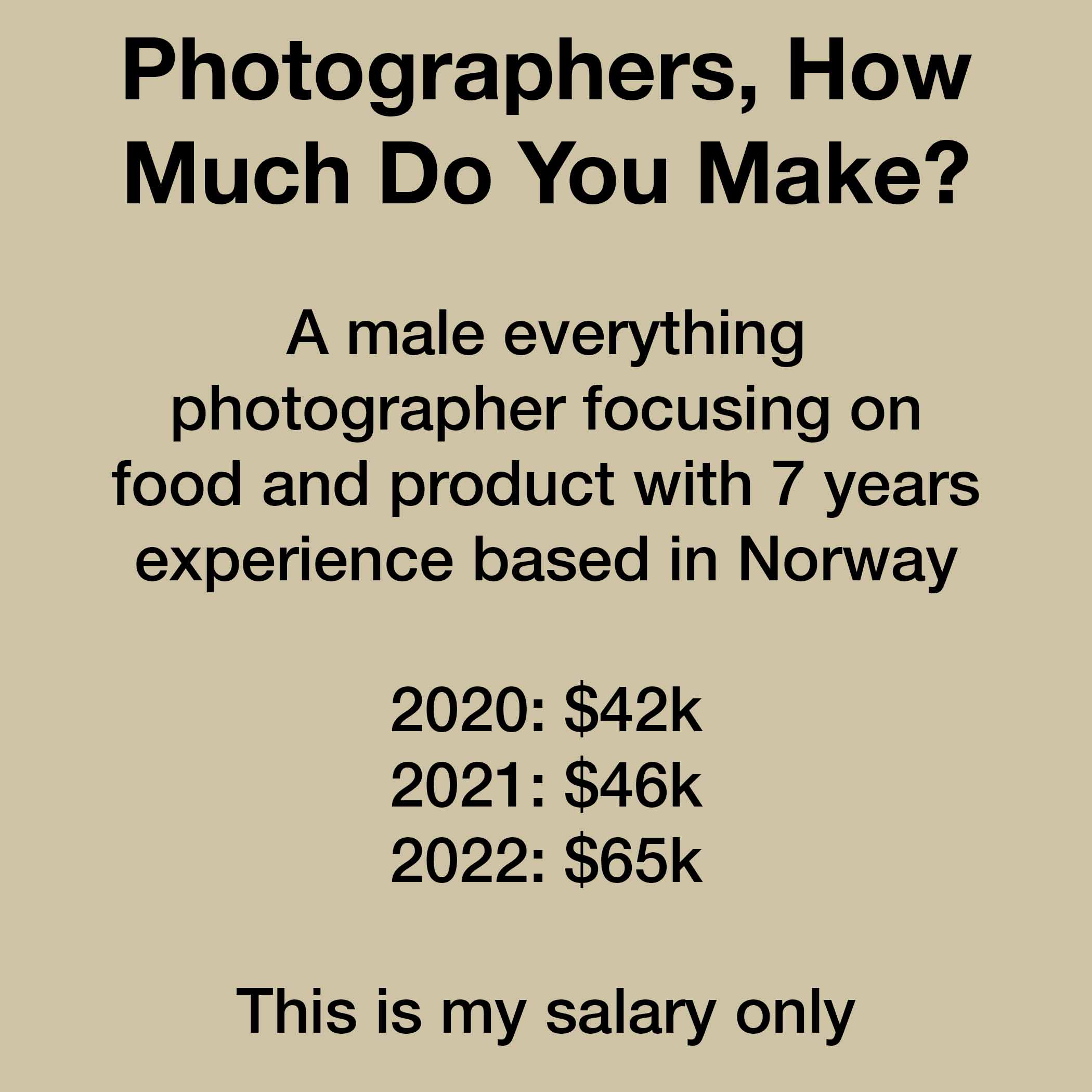

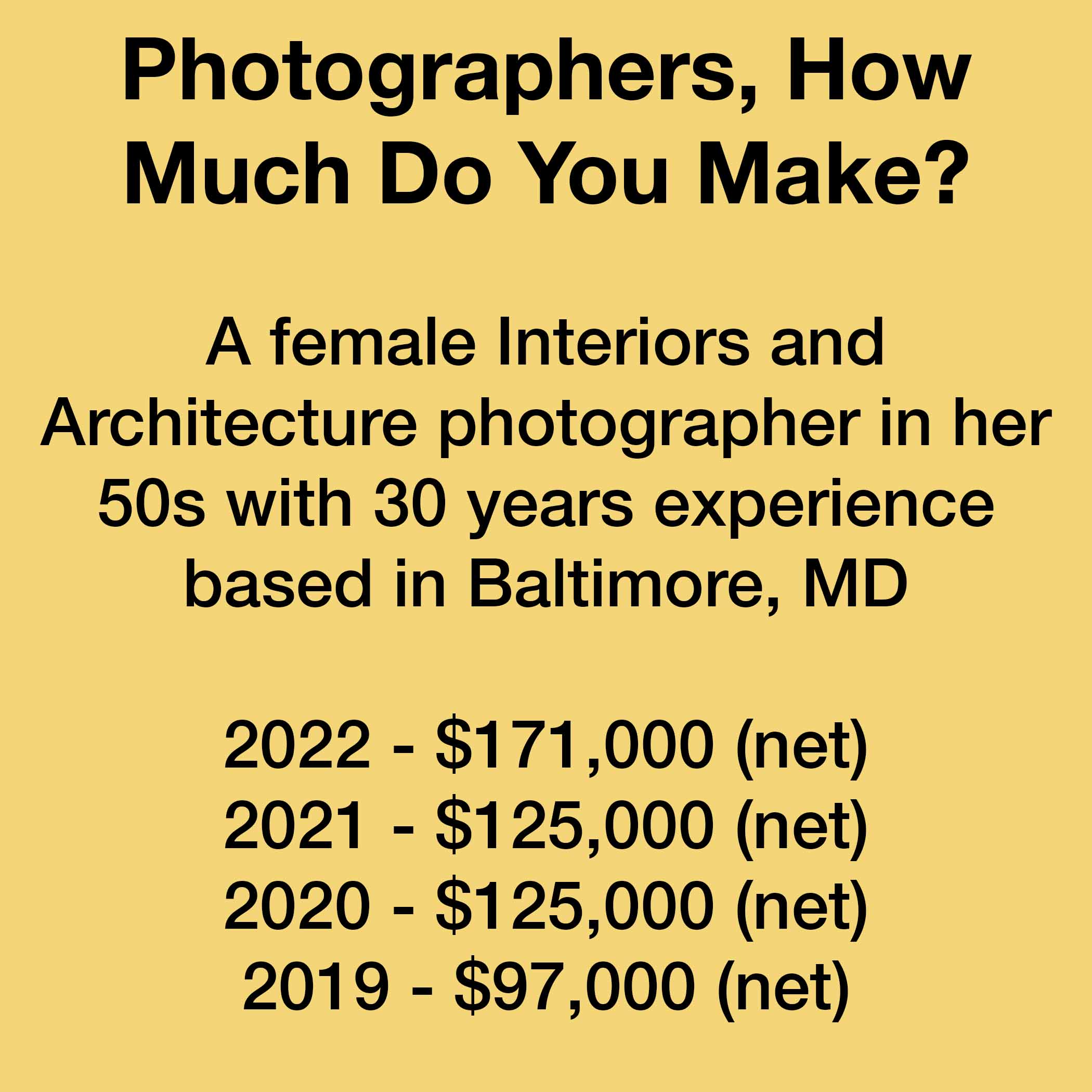

I set aside the profit every year after expenses as cash flow:

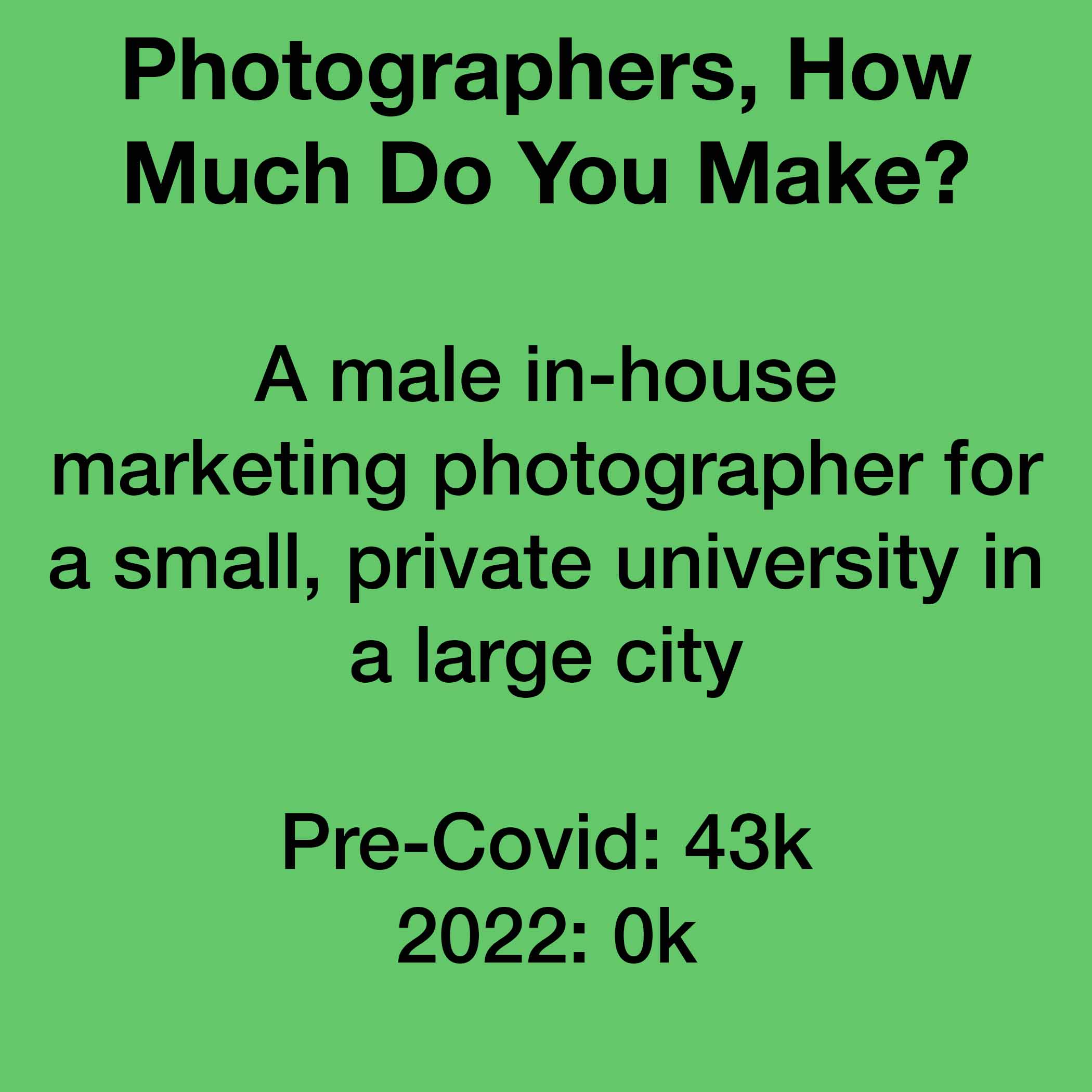

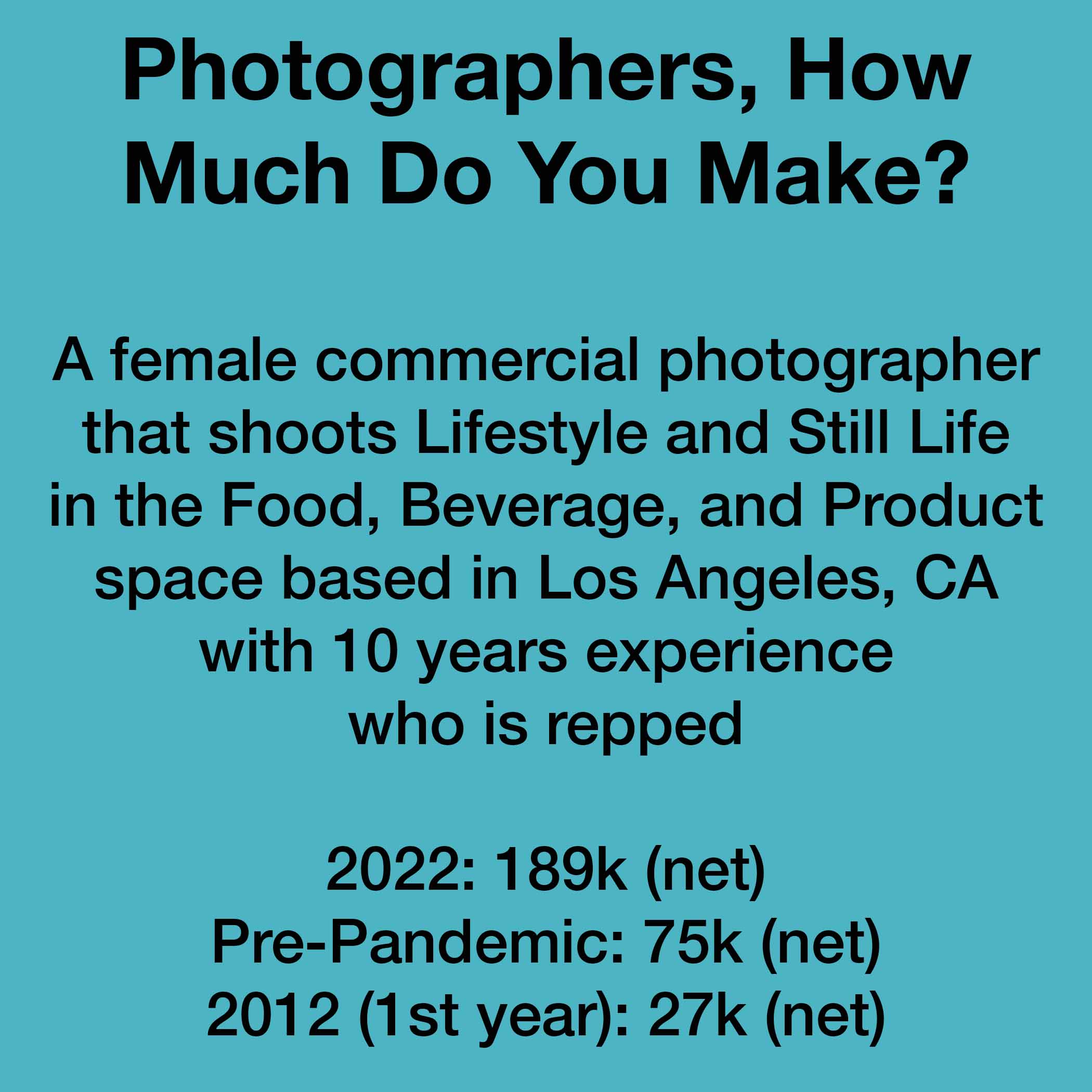

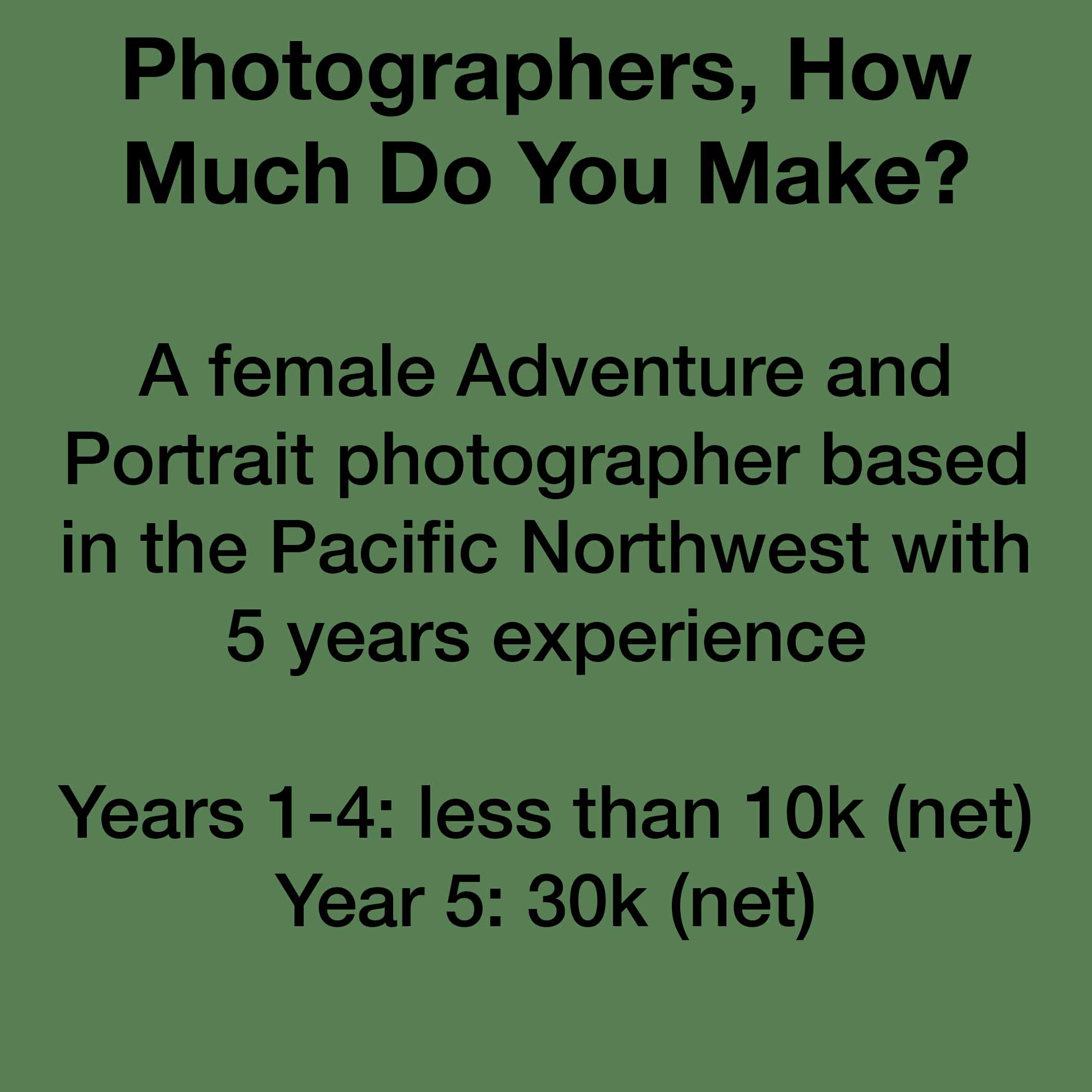

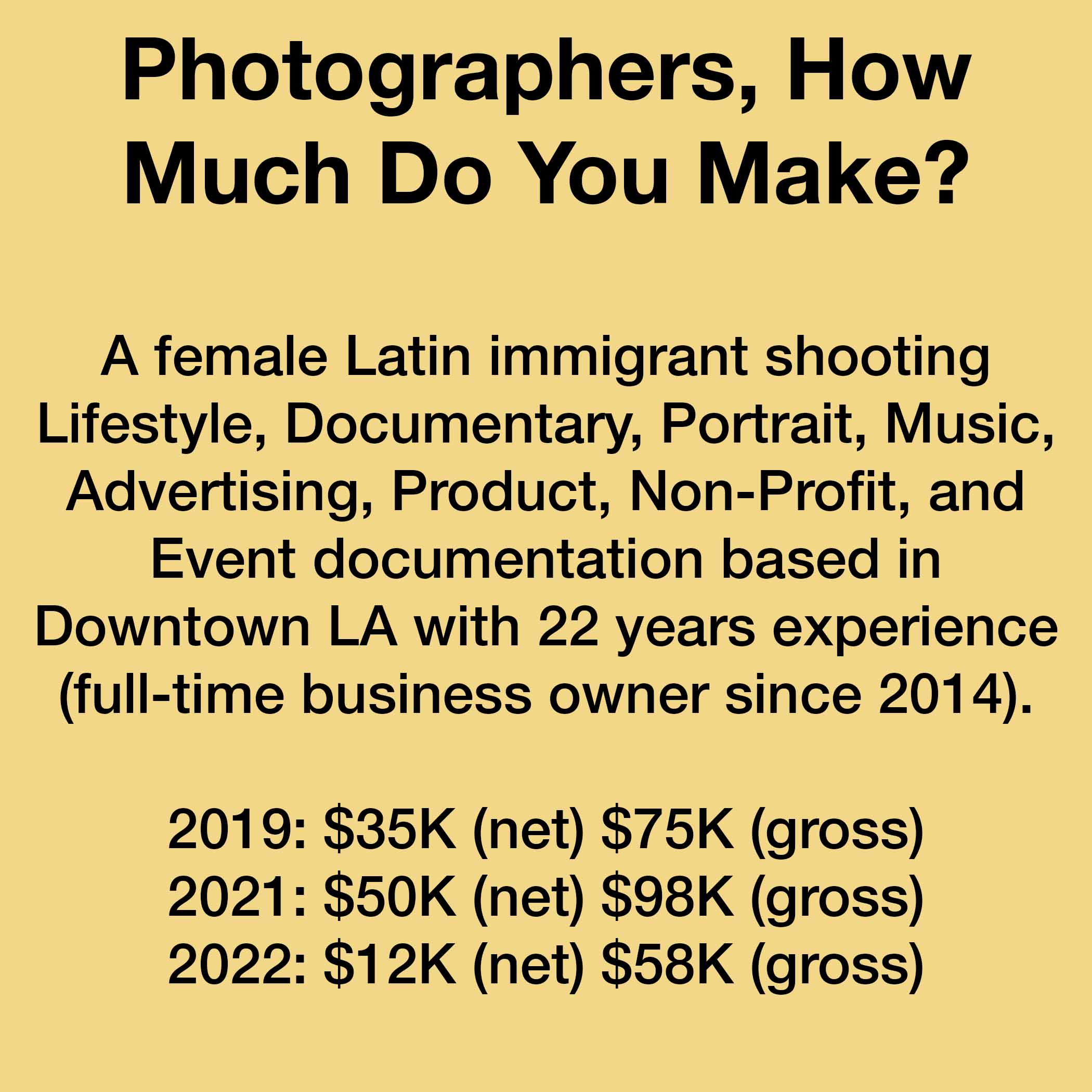

2020 profit: -$2k

2021 profit: $17k

2022 profit: $40k

Note: numbers are USD.

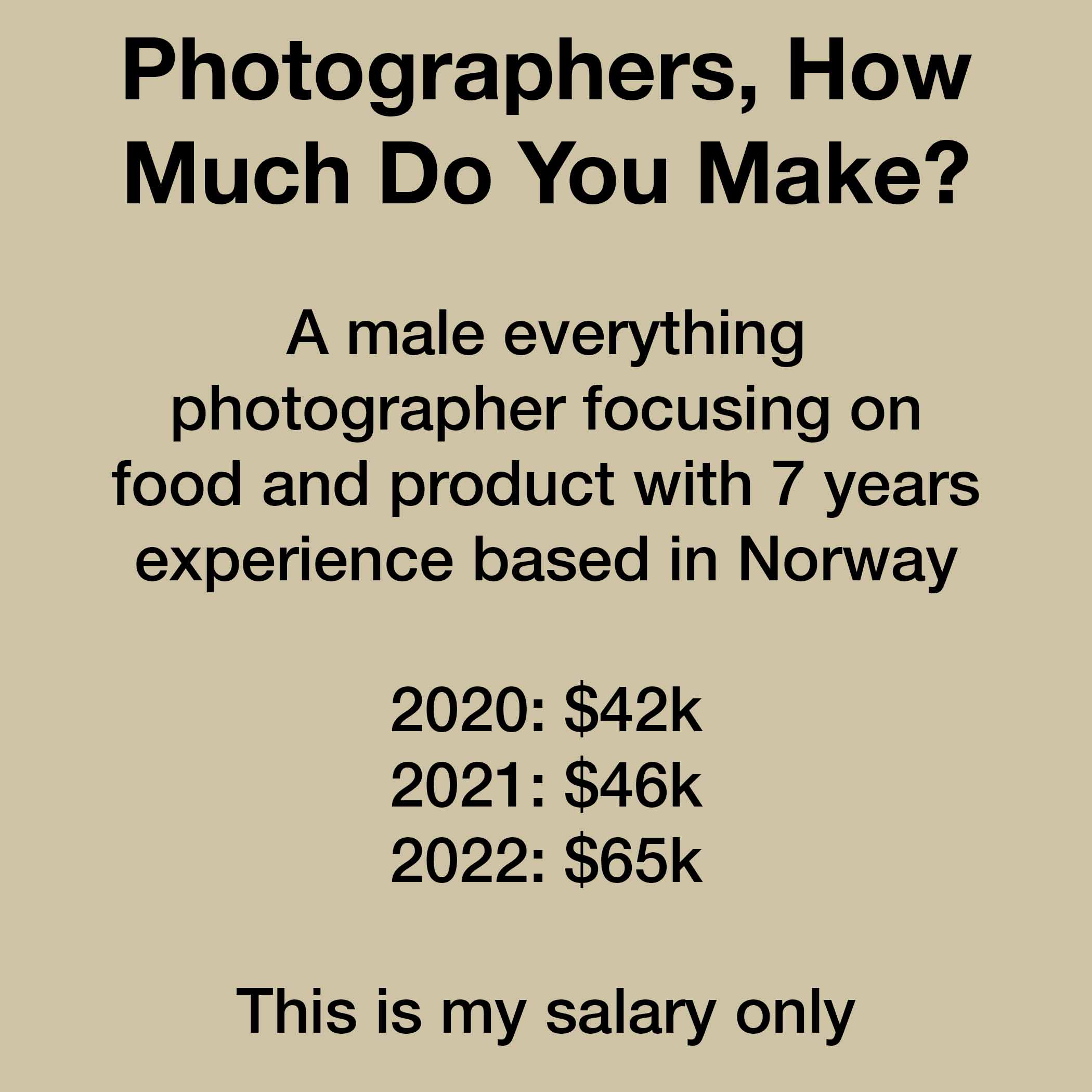

I’m a bit of a jack of all trades, but I try to focus on food and product photography. Though I find specializing is close to impossible because clients care more about getting a low price than amazing results. As a photographer, you’re more likely to get hired because you know someone looking for a photographer over being the best in your niche.

15% food, 30% product, 10% portrait, and 45% commercial.

I only hire freelancers when I need them, and my overhead is:

Studio: $25k

Leasing: $8k

Employee fee: $9k (basically what you pay to be employed – it’s weird, I know..)

Profit margin varies but is about 12-18% each year after expenses and salary.

I basically work every day, but that includes everything from administration, accounting, and other boring stuff. In pure shooting days, probably around 60-80, with the majority of them shooting along side a film crew. I also do my own retouching, which adds in about 70-100 additional working days.

My clients are nice and easy, but also very boring. They lack creativity or even the ability to be creative, so when you present anything creative, new, bold, or whatever – they find it scary. That goes for both ad agencies and direct clients. The Norwegian style in advertising has been the same for 20-some years. I almost got in a copyright lawsuit a few years back when a new and fresh ad agency wanted to do something “cool.” They had basically drawn a photo they liked and presented it as their sketch for me to do. That is how creative some art directors here can be. But there is also the 1% of clients who wants you to go nuts. I call them the holy clients. They’re rare, far between, but they exist. Just have to search and market correctly to find them.

My income over the last few years has been pretty steady but not high. Roughly an average yearly salary here. But in the last two years, it’s been going up, though in 2023, there have currently been no jobs and none in sight. So a solid $20k minus already. Video has killed photography I rent out my gear and studio as much as I can to bring down the costs.

Usually, one day of shooting is roughly $4000 for 10 images.

Day rate: $1700

Retouching @ $150 pr. image (varies from $80 to $300)

Studio @ $400 per day

Equipment @ $300-500 total (camera, lighting, digi etc.)

Licensing: First year included, 50% of day renewal fee.

My day rate varies from $1500-$2500, which also includes a one-year full buyout. Licensing has basically been wiped out, and if you can charge it you’re lucky if you even get the job.

I had a shoot for a German company. It was two days of shooting at $1500 per day with $3000 in retouching and a 5-year worldwide licensing at $18k. That was my first and only time getting a license fee at a really good rate.

Even though the fees are low here, it’s pretty stable. I name my price, and I either get the job or I don’t; done deal. I think that’s pretty common in all of Scandinavia. Based on the price examples on your site, it would seem to vary more in the states.

Video is about 10-15% of my income.

As much as everyone preaches for specializing, make sure you’re in a country or a market where specializing is actually possible. Adapt accordingly. Shoot more personal projects to become better. Work harder on your portfolio than on paying jobs. That’ll make you happy when you work in a place where the clients don’t care about the end result.