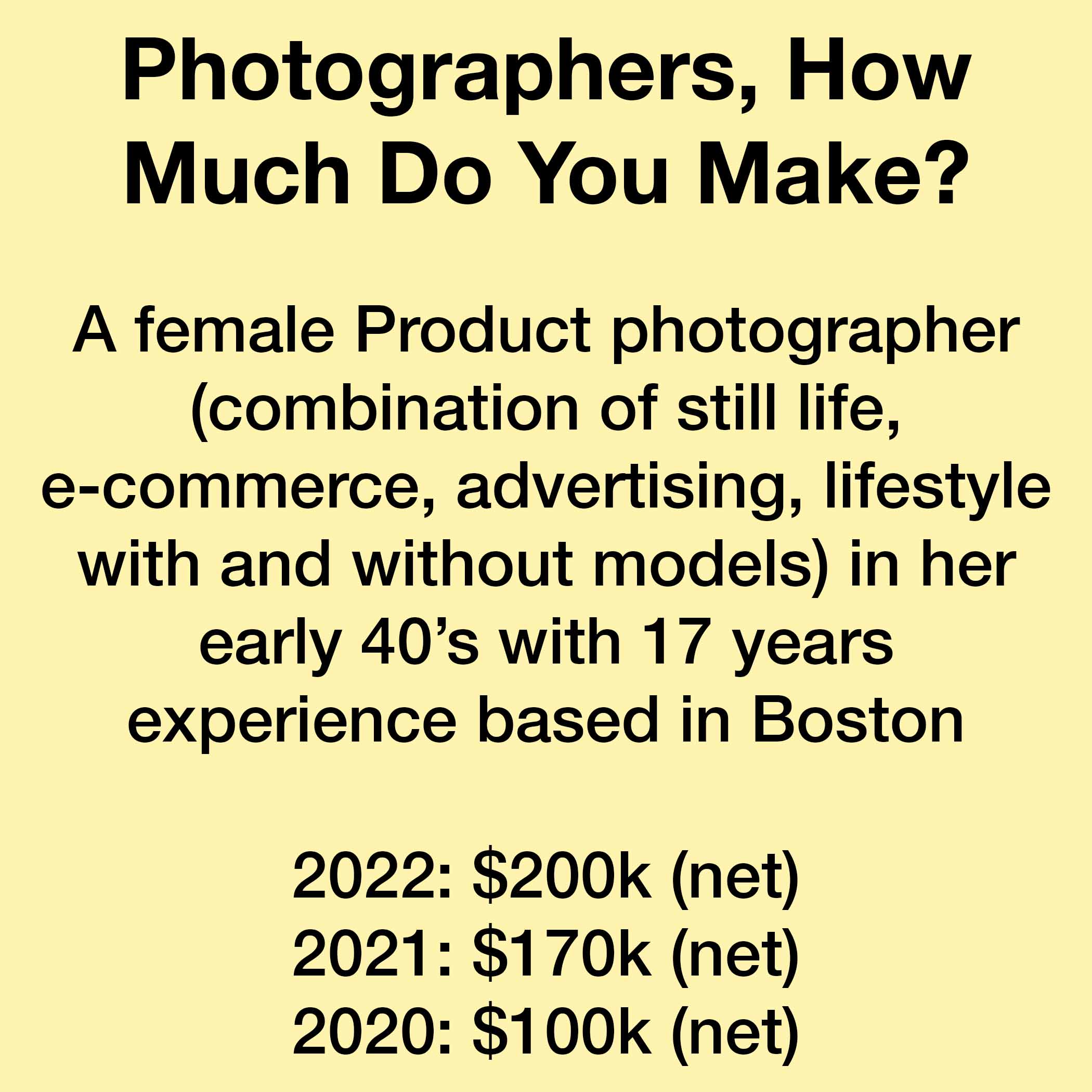

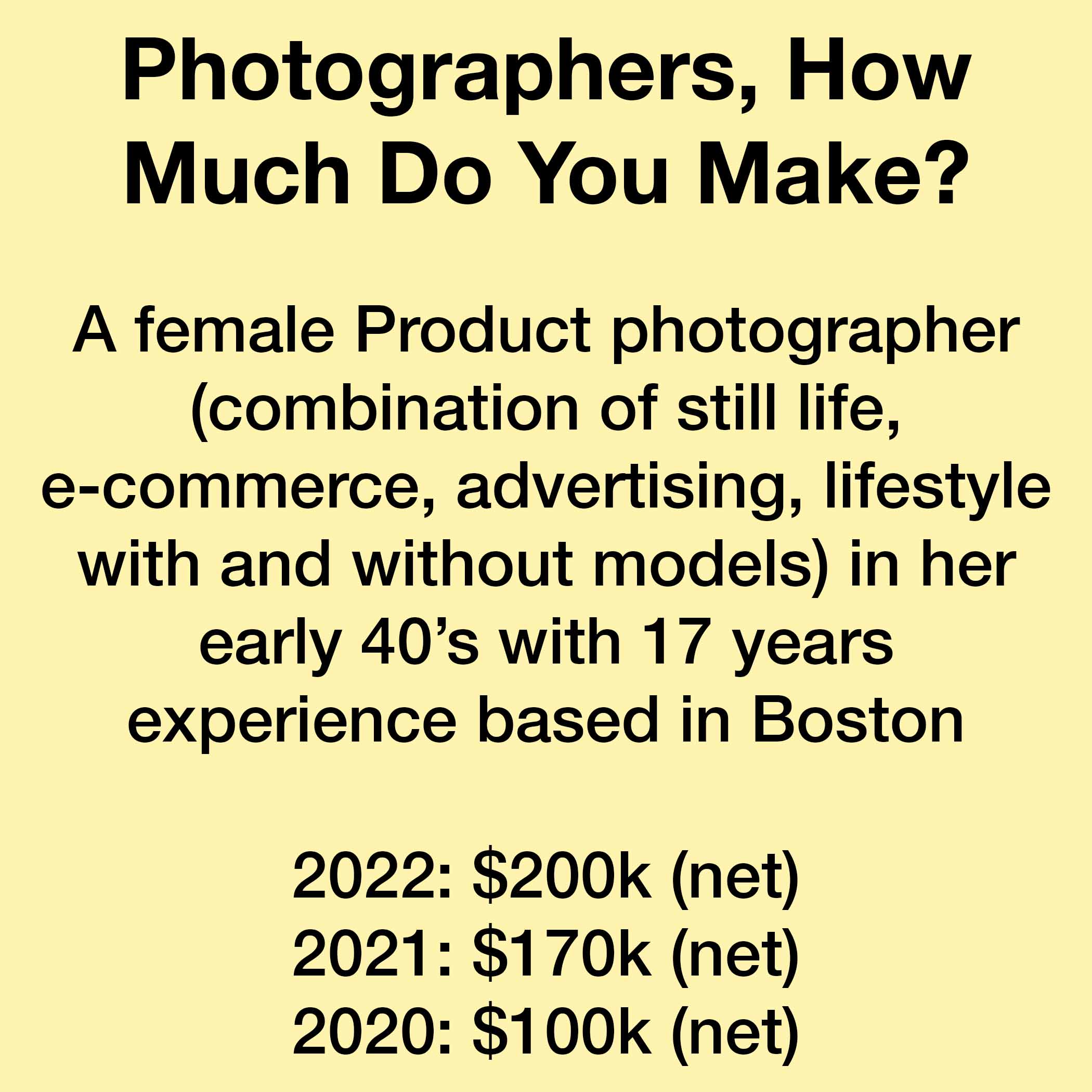

Product photographer is a great style to work in because it’s an umbrella term. So all my work is product photography but I can shoot it in studio, on locations, with talent and without. A guess is 70% of my work is some version of product still life and 30% is product with models/talent.

I’m in the Boston area but my clients are up and down the east coast ranging start ups to well established international brands.

I used to have and agent but currently prefer not to have one because I get to know my clients better.

My overhead is low. My studio rent is less than $1/sqft (I got lucky finding a spot in an artist building during the pandemic when a lot of people left). Most of my costs are production costs since I handle a lot of that myself.

I’d guess my profit is around 80%. Last year I billed $250,000 and my taxes were on $200,000.

I work 35-40 hours a week about 49ish weeks a year. Some weeks, like when I travel, I might have more hours but that’s probably the average. I rarely will work after 5 or on the weekends. I’m a mom and that’s my highest value family time.

Most of my clients are building some type of image library for online usage. There are occasional simple product photos that are also frequent calls which I can do pretty fast. The majority of my clients are repeat. Some book me for a few days every month, others maybe 5x year for their seasonal campaigns and quite a few are 2-3x a year and somewhat smaller companies. The thing they all have in common is I tend to be low maintenance with my clients and run smaller productions. I do a lot of remote shooting where the clients review relevant images as we go so they can stay in their cities, take regular meetings and have a normal, albeit somewhat disruptive, day at work.

Over the last few years my income has been going up consistently. I spent a lot of time in the south and gathered some amazing loyal clients down there but moving to the Northeast was a huge bump for me.

I run most of my shoots almost from top to bottom so I’m often doing the productions/styling/shooting and retouching. When I start to get too busy to do all those, I’ll hire my assistants hourly to do some of this running around. I think it’s been part of my success being involved in all those aspects. I know my repeat clients so well that I can minimize what I need from then to deliver on brand content.

I’ll get an initial shot list and review it with the client. I’ll do the production which will usually take less than a day, maybe 3-6 hours depending on the shoot, (billed hourly). Then we will shoot and after I’ll retouch the files and deliver them. I bill most of my work as hourly with online usage added into the hourly shooting rate (I know about how many pictures we can do in an hour). Extra usage is added per image to the invoices.

My shoots range from a half day to weeks and weeks of shooting so average isn’t really a thing.

The bigger the project the more hours it take and work it is. I have projects that were over $40k by the time I invoice for them but they might have been work that went on for a while. A couple weeks ago I did a shoot where the estimate before retouching was $20k for a week of shooting with fairly low usage. Next week I have a shoot that might be a in the hundreds of dollars that’s 8 pictures of 4 products for a website. By charging hourly I feel like I am accessible to people of all sizes and my motivation as a photographer is to help out whoever I can. I try and be completely fair to everyone in what I charge and if I can squeeze someone smaller in and help elevate their images for them, I will.

My worst paying shoot lately was one the client (an agency) produced and styled. When I got on set quickly what had been discussed as needed on calls was the tip of the iceberg, but I had a creative fee with my day rate on the estimate, based on what they had discussed with me and had been on the shot list. Each shot on the shot list looked was worded as 1 image but on set they realized they had the language wrong and meant for overhead to mean straight on camera angle making it two shots and that each shot was for 1 product with 6 color options and for both the new and old model. So the math on that was what looked like 1 image and was estimated to be usage and time for 1 images was 24 images. There was also a request for the raw files which hadn’t been discussed. It was an ambitious project for a one day shoot before multiplying the shot list by 24 and the day went long. But that wasn’t where issues ended.

I billed as fairly as I could including travel and overtime. The client came back and argued that they were over budget already and I hadn’t ever clarified a day had an hourly limit to it so I couldn’t charge any overtime. I assumed as they were an agency and we had 4 models it was understood that 10 hour days were what we were working off of but I did remove the overtime charges. They also wanted me to take off the travel fee, because a lower level employee never mentioned to them I charged that. Since we did have written discloser of that (despite it being to a lower level employee) I kept that on. I still paid my assistant overtime because obviously I want to do right by my assistant and they shouldn’t be effected by this stuff. Then they were about 60 days past the payment terms when they finally did send payment. I also waived their late fee but honestly, I’ll never work with them again. Lesson learned there.

I think my average cost per delivered shot was one of my lowest in a long time. Also having them style the shoot was a bit hard to watch and there wasn’t time allocated for me to try and fix things for them. I can’t imagine their client was super happy with the results.

I will occasionally do some video but I’m not shooting it. I’ll hire in a team and we’ll work together with me as a director. This is very sporadic though. Most of any motion work I do is created from stills.

Worst advice I’ve received: You have to pick one thing to shoot and perfect it. You can’t move once you have established yourself either.

*So I picked products because I can change what I’m shooting all the time, keep on challenging myself and getting creative. I’ve lived in 4 different cities around the country now. I focused on creating a business model before the pandemic that did remote shooting so I kept most of my clients and moving allowed me to get a presence in more markets.

Best advice I’ve received: Love what you do, have gratitude for every day and experience.

*I will set intentions before my shoots for the best possible outcome or to exceed the expectations of myself and my clients. If things don’t go as planned, allow it and it might surprise you how it works out. But life has too many things that can go astray to let our creative processes become stressful. Being creative in a joyful and grateful state always produces better images for me.

My most effective efforts in marketing are SEO work: optimizing my google listing and being intentional with what my SEO is targeting. I have and had some memberships to organizations like Found and Wonderful Machine but I don’t think they’ve ever really been worthwhile. I have hired photo editors to help me redo my website which I’ll redo every 3-5 years. I moved away from website template platforms like Squarespace that just can’t get their SEO game up to where WordPress is, which is what my site is build in now. I can make the site look exactly how my consultants and I want it to but have all the SEO optimization that the template sites aren’t doing (I know they say they are but they really aren’t as good). A good website with strong SEO is amazing.

My retirement is traditional at the moment, 401K and Roth IRA. I’m exploring passive income streams but haven’t settled in on any yet. Everything I do is B2B and the passive income I keep thinking of is all B2C which I’m not as crazy about yet.

I’m particularly interested in this topic among photographers as it’s often not considered. It’s a question I ask when I meet up with other photographers in my cities (which is something I try and do, I don’t want to compete with them but I want to know who they are, what they are doing and build team mentality if possible as we all bring different skills to what we do and I can often refer work to someone else better if I know them). I collect their plans and have heard everything from selling stock and harvesting usage for years to come to marrying a lawyer!

My thought of what might help photographers is a request of you, actually. I think you touched on it by recognizing that there might be an earning disparity between female and male photographers. I am wondering (and not going to lie, this curiosity is part of what prompted me to participate in the survey) if across the board other photographers are noticing this pattern: 95% of my clients are female. From the 5% that consists of my male clients none of them are from the US. They often live here now but were raised somewhere else.

Of course it is possible that my style resonates with a female audience but I’ve seen this for the last 10 years or so. It’s another question I ask fellow photographers that I become friendly with. When I’ve chatted with friends who are male photographers, they see a good mix of both female and male clients. However my female photographer friends I’ve asked also have a large gender difference not dissimilar to what I am experiencing. It’s peaked my curiosity and I wonder if someone asked photographers about what gender and nationality is hiring you, if this pattern would be widespread or regional. I think adding that question and learning if there is a pattern would help photographers.

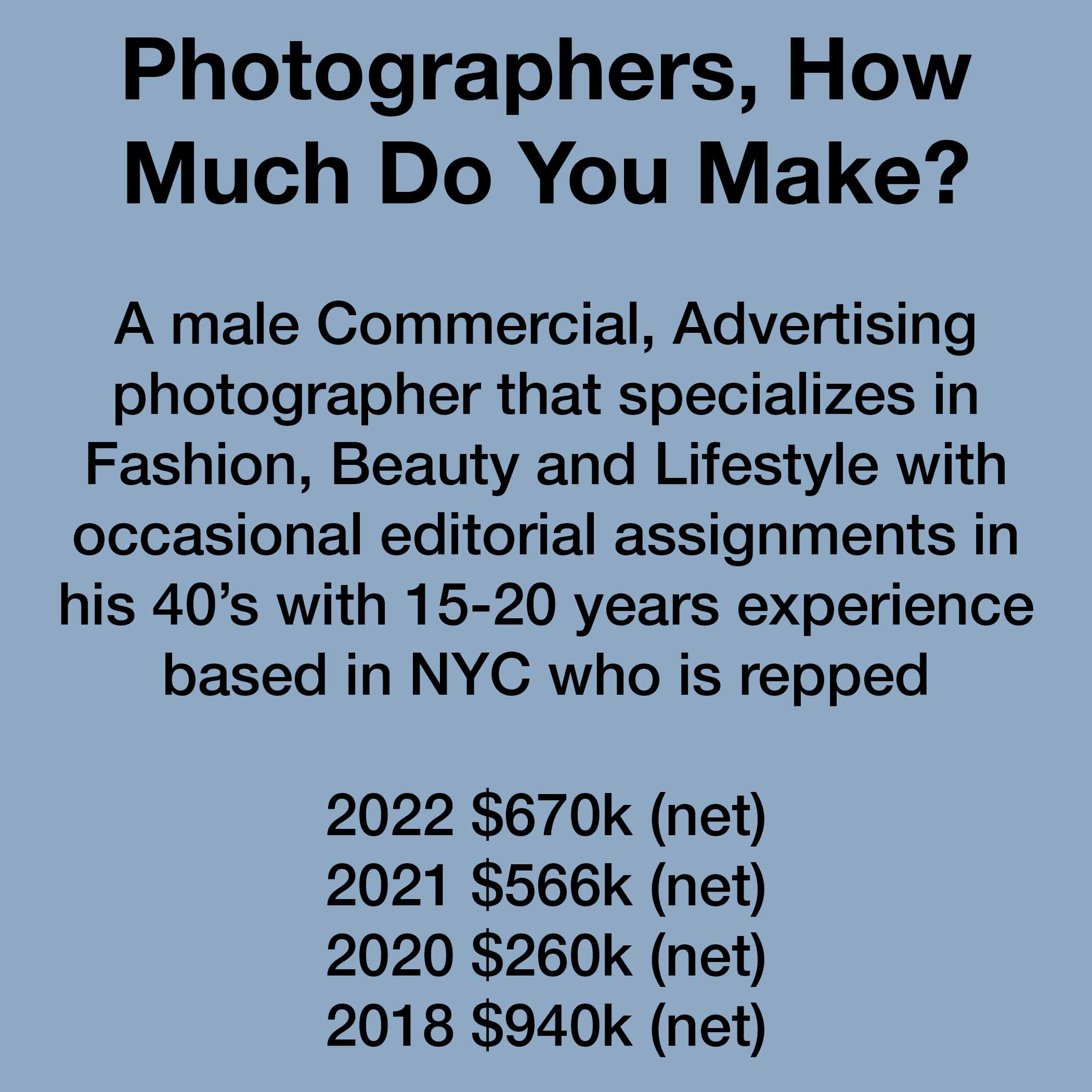

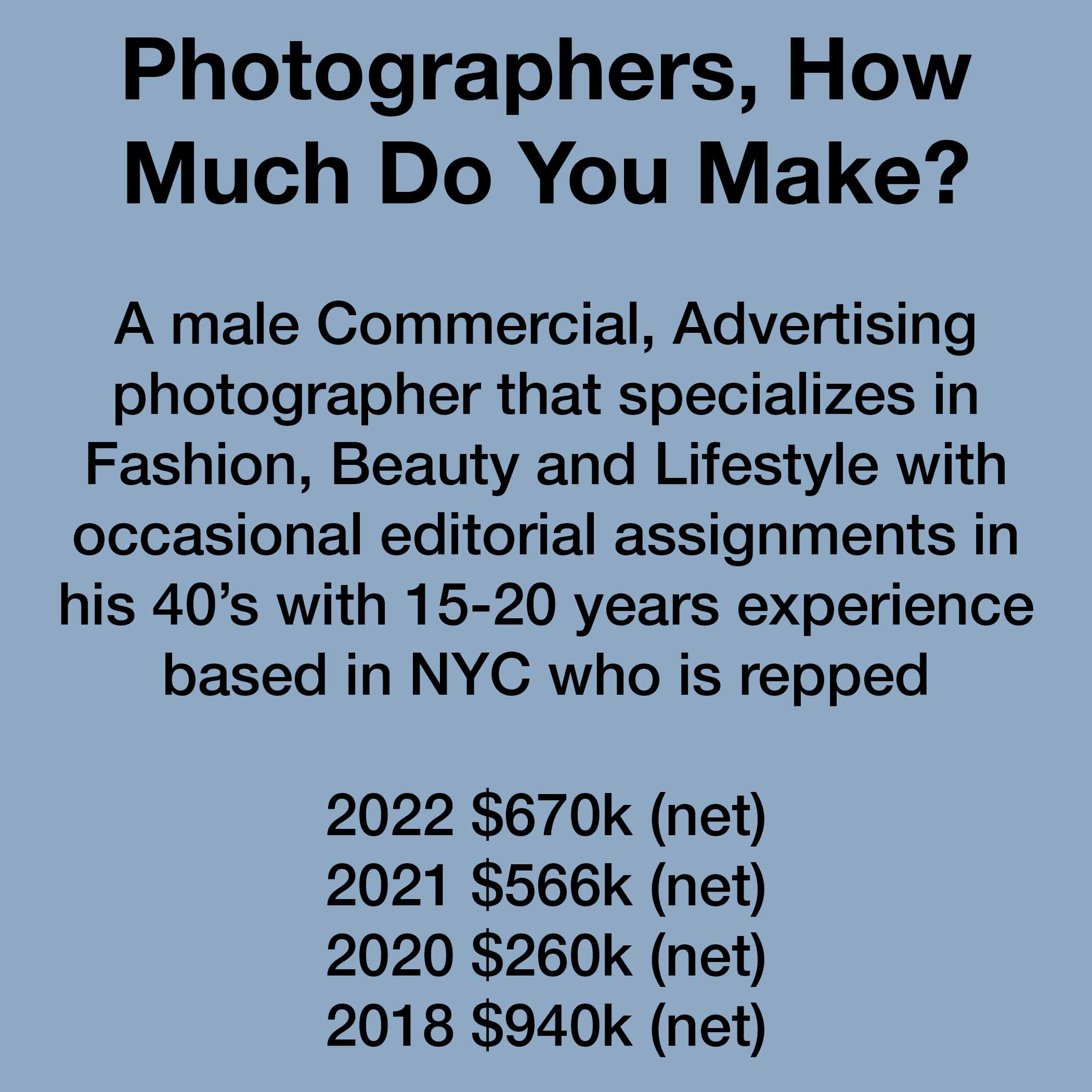

I have a diverse collection of clients ranging from Luxury Brands to Fast Fashion to Beauty Brands. I shoot Advertising campaigns, Editorials, Catalog (both studio and location) Executive portraits, Point of Sale, Branding, Marketing & Web and occasional Video. My personal work is a mix of portraits and landscape photography. My clients are all over the USA. My rep takes 25% of the negotiated day rate.

Before COVID, I had a full time First assistant.

My overhead I try to keep minimal. I have a storage unit, and a small office. My biggest expense would probably be updating equipment & transportation.

I have averaged 50 days of work in 2023 so far (On 3/24/2023). Every year is different, but I try to average 2 to 3 weeks of work per month.

My income dropped significantly due to Covid. I found creative ways to make money in photography and luckily I am so diversified in my work, I had opportunities with a few clients that took me on location but I had to isolate for weeks before I could arrive on set.

In 2022, I rebounded and my income has been slowly increasing since Covid. I suspect there will be a few rocky years ahead.

I have a small production company that I use to sub rent part of my photography equipment and pay my freelance staff. This helps not dipping into my photography rate. This supplements the high cost of updating equipment and paying freelancers a higher day rate than what clients are willing to pay.

Average shoot day on location is 12 hours. I do not charge OT as a photographer. My freelance assistants charge OT after 10 hrs. A lot of clients are reluctant to pay OT to crew. Terms vary for client to client and usually there is a 1 – 2 year embargo on the images. Most fashion clients don’t need to renegotiate usage but occasionally they will for an extended year or two. The biggest renewable usage personally comes from Beauty that want to extend their product packaging. Occasionally, celebrity images can get syndicated and there can be additional money compensated.

My best rate in the last two years was a National Advertising Campaign that paid almost 20k a day (minus commission) and the best usage was a multiple images syndicated for a National Marketing fashion company that paid 32k.

My worst rate in the last few years was a National syndicated Editorial Magazine $600 a page plus expenses limited to 2k.

I’m a Director of video and I also shoot Video. It’s something I’m exploring more and more.

My marketing is primarily relationships and social media.

I hope not to retire, but I have something similar to a 401k plan for freelancers.

The worst advice I’ve received was:

1.Move to Europe.

2.Shoot one thing really well. Specialize in it.

Best advise was:

Own your own Eq and start a LLC.

My biggest advice to photographers is to diversify and learn video.

-Diversity !!!!

-I almost don’t turn down any job no matter the rate. Unless I feel like I’m being taken advantage of.

-If you take the assignment, job – deliver 200%.

-Raise the bar so high that they can never go back.

-Know your worth and how much value you bring to the table.

-Be kind. Always. Take good care of your crew and pay your freelancers more money than what the clients are willing to pay.

-Don’t take things so literal- bring your creative talent to the table but understand what the clients vision is.

-Learn lighting techniques and understand how lighting can really enhance your work without doing it in photoshop

-Have an emergency fund (it was a hard lesson).

-Never take your clients for granted and appreciate every job that is awarded to you.

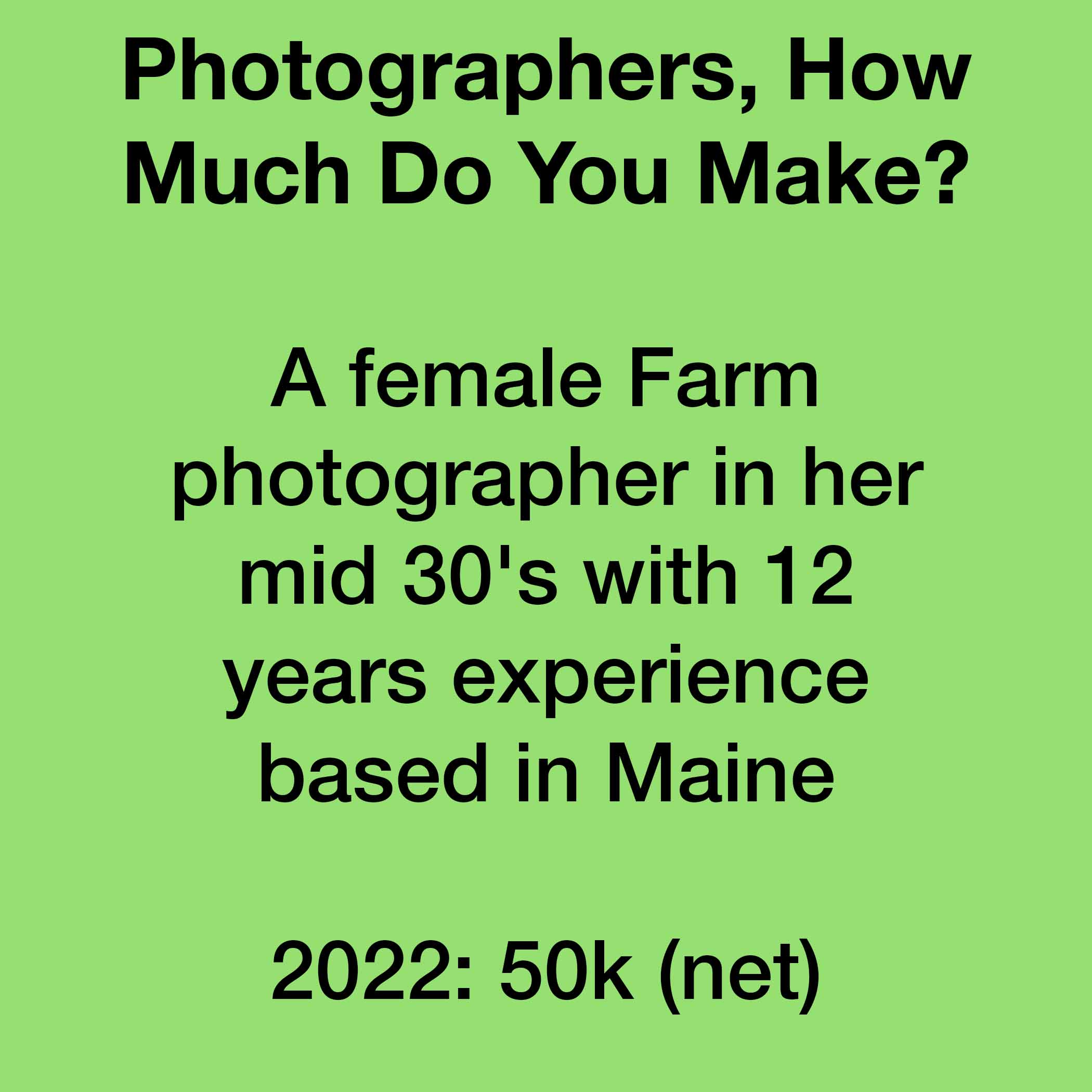

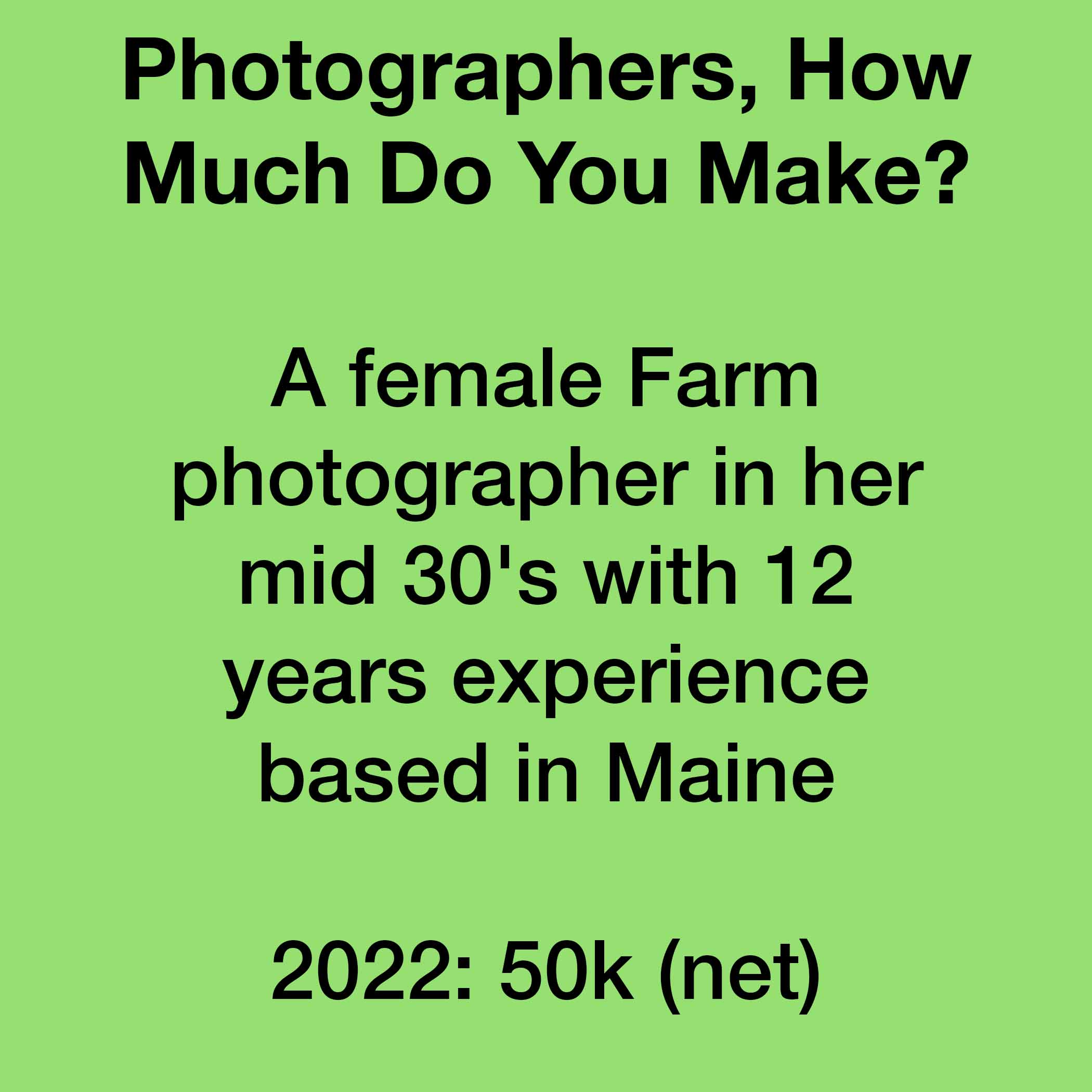

12 years ago I got my first paid gigs and I’ve been working 5 years as full-time photographer.

My clients are small and medium farm businesses, larger food and farm nonprofits, food councils, etc., mostly paying for my work through grant funding. They mostly have a pretty chaotic/sporadic communication style and approach to planning and scheduling (because that’s farming) and that works well for me, too.

Estimates of how my income is derived:

20% Ongoing contracts with just a couple of farms for comprehensive marketing photography including product photography

20% One-time half day doc marketing job for small farm businesses

20% Infrequent but higher paid jobs for food organizations, local food businesses, or food nonprofits

13-15% Assisting/seconding other photographers

10% a seed catalog

10% or less – pickup licensing or publication, random print commissions

10% or less – Editorial assignments. My average pay per editorial job is $600, which I think might even be above average, with most jobs taking multiple days of work.

I do not have a lot of overhead:

$1-200/year on weather gear: boots, socks, rain suits

$30/mo health insurance for me (thanks, lower income bracket)

$300/year on computer maintenance and software

$1K/year on gear & liability insurance

$1-2K/year average on hardware: memory cards, hard drives, occasional lens or body replacement, thumb drives for clients, camera accessories like cleaning stuff and replacements for things I break and lose

The mortgage on my house + utilities comes to around $12k/year, split evenly with my partner (this is the only debt we have)

I have a paid-off used hybrid vehicle who’s gas mileage makes me money after the federal mileage reimbursement. Maintenance + tires is around $500/year

My office is in my home, so utilities for the space are a write-off.

I do not know my profit margin but the goal is to have enough to get to do it again next year.

I work maybe 300 days a year. Networking within my community is a huge part of my work, and that happens when I’m hanging out with friends or shopping, etc. I use social media almost every day, which drives word-of-mouth referrals. I’m always scheming. I work with a camera in hand about 90 days a year, and at my desk about 180 full days a year. The rest of the days I work when the mood strikes. Being able to change plans last-minute is important to my niche.

I’m up about 20% from the first two years going full-time, and pretty steady the past three. I dropped family and event work, which has been awesome for my mental state and endurance, but those were the better-paying jobs. It balances out with new clients because my reputation is still growing.

My other source of income is second-shooting for an awesome high-end wedding photog and I assist for a couple of pro commercial photogs. I make around 6K annually between those. It’s paid professional development!

My partner makes less than me, and neither of us have family money coming in. For indirect income, though, we both get free local food through our work and I love to preserve seasonal produce, so our grocery bill is less than $200/month.

The usual is a half-day for average $900 last year. Usually includes an hour of travel and 3-4 hours of camera work. Then archiving and editing can be another 6-15 hours including paperwork, drives to the library to upload or post office to mail thumb drives, and being at the mercy of being in the right mindset to grind through creative work or do it in small spurts.

First 40 images are usually included. My rural internet upload speeds are atrocious, so only higher-paying clients who need it get galleries to select for licensing. The rest get what I choose. Licensing terms vary by client, sometimes 2 year, sometimes 5 or 10.

In the past I’ve tried to do the math and make sure I’m paying myself at least $50/hr for creative work but I think it’s probably time for an increase.

My best paying recent job was a restaurant group that hired me for authentic doc images of real farms they work with. $4,500 for three half-day shoots, 50 images per day, 10 year nonexclusive license. Take home was over $4K.

Worst paying jobs are always publications. The single worst was a 5am start 90 minutes away in winter (bad weather on roads). I stayed photographing for 2 hours, spent another 2 hours archiving and editing, and two more hours driving to a library and uploading files to deliver (yay rural living). Pay was $225, magazine retains one-time print use and indefinite web use, I can’t re-license for 6 months past publication. It would be great to get fair pay, but I’m glad I did it because the editor is rad and my client base pays attention to the magazine and is impressed by seeing my work there.

I have occasionally shot and delivered raw video footage for client to edit as part of a larger photography job. Not super into it but would do for the right project.

I have a very small retirement plan from a previous day job, plus SSI (I hope) from all the other odd jobs I worked between ages 13 and 30.

For the real pros like most of these interviews, I have no advice except that if you’re able to take a pay cut, doing only the jobs you really want to do is exhilarating! I’m super curious to see how people will respond on here to my lower income and rates.

For newer, younger, or transitioning-to-professional photographers:

If you ever want help or referrals from other photographers, do not ever advertise or mass-solicit free work. Get involved with local businesses or organizations in other ways, become a person people know, and then show that you do photography. You can’t fast-forward community relationships. If you don’t need to make money but want to be a working photographer, charge a fair rate anyway and donate it, or self-publish a photobook.

You need to remember other working photographers are your colleagues, and undercutting them is not only evil but it will hasten the death of the industry you’re trying to get into.

No one talks much about class disparity in photography careers, and the only people who seem to be aware of it are of a lower economic class. In the beginning I was lucky enough to have my health, a stable living situation, low debt, and no dependent family members. I started out working as a second for a wedding photographer I found on craigslist, with a D70, used D300, a $90 50mm and a kit lens. I lucked out again in that she was an awesome mentor who helped whip me into shape. I continued taking small odd photography jobs for people I already knew while working full-time day jobs, buying better equipment with the money from gigs. By 2017 I made around $25k with annual rent of about $6k–another thing that’s really tough to come by now.

After I had a year’s expenses in savings, I quit my day job, and let everybody know I was going full-time on photography. I took a lot of jobs I shouldn’t have because they weren’t work I cared about, but it showed me that the money would come. You don’t necessarily need to be a rich kid or have a higher income partner to be a working photographer, though it felt like that to me all the time as I was trying to get into it.

A lot of what you see other local photographers doing on social media might be an illusion of work or success: publications don’t pay a living wage, and there are a lot of people who frame personal projects as hired work without explicitly saying it. If you love your work, bite down hard on it and don’t let go.

Top three best advice I’ve received for my career:

-Show what you want to do more of, don’t show what you don’t want to do (in your portfolio/website).

-Do the best that you can in the place where you are

-La fruta madura cae – “ripe fruit falls,” which reminds me to let time do its work as I build my career.

Worst advice (for me): Follow the money if you want to make it. I’d be doing wedding videos if I had followed this, not that there’s anything wrong with that. Instead I made up a role for myself and the money followed me.

Knowing my shit about my niche is what sets me apart from other photographers. There are hundreds of photographers here doing top-quality work and running legitimate, professional businesses, but if you’ve never worked in farming yourself, you have no idea how much you don’t know about it. I’ve heard stories of photographers getting sent to local farms and bragging about their contract with a cheap national restaurant chain, publishing non-food safe images that could cost a farmer their licensing if the wrong person saw it, having no concept of the pace or pattern of work on a farm, no understanding of biosecurity between livestock herds, licensing an image of a farmer for a billboard about health insurance in another state, when the farmer themself didn’t even have health insurance, and on and on and on. Local farming is also a super tight and tight-lipped community, so doing an assignment about someone everyone else knows is a real a-hole will reduce your legitimacy. Not being aware of class differences is also a barrier for outside photographers to earning trust.

I lived and worked on a farm here for four years, and have continued to work with the same farms and markets for over a decade. My integrity within the community combined with the quality of my work is my best marketing effort. TLDR: It’s 100% word-of-mouth for me, and it works because I am actually a full-time member of the community I photograph.

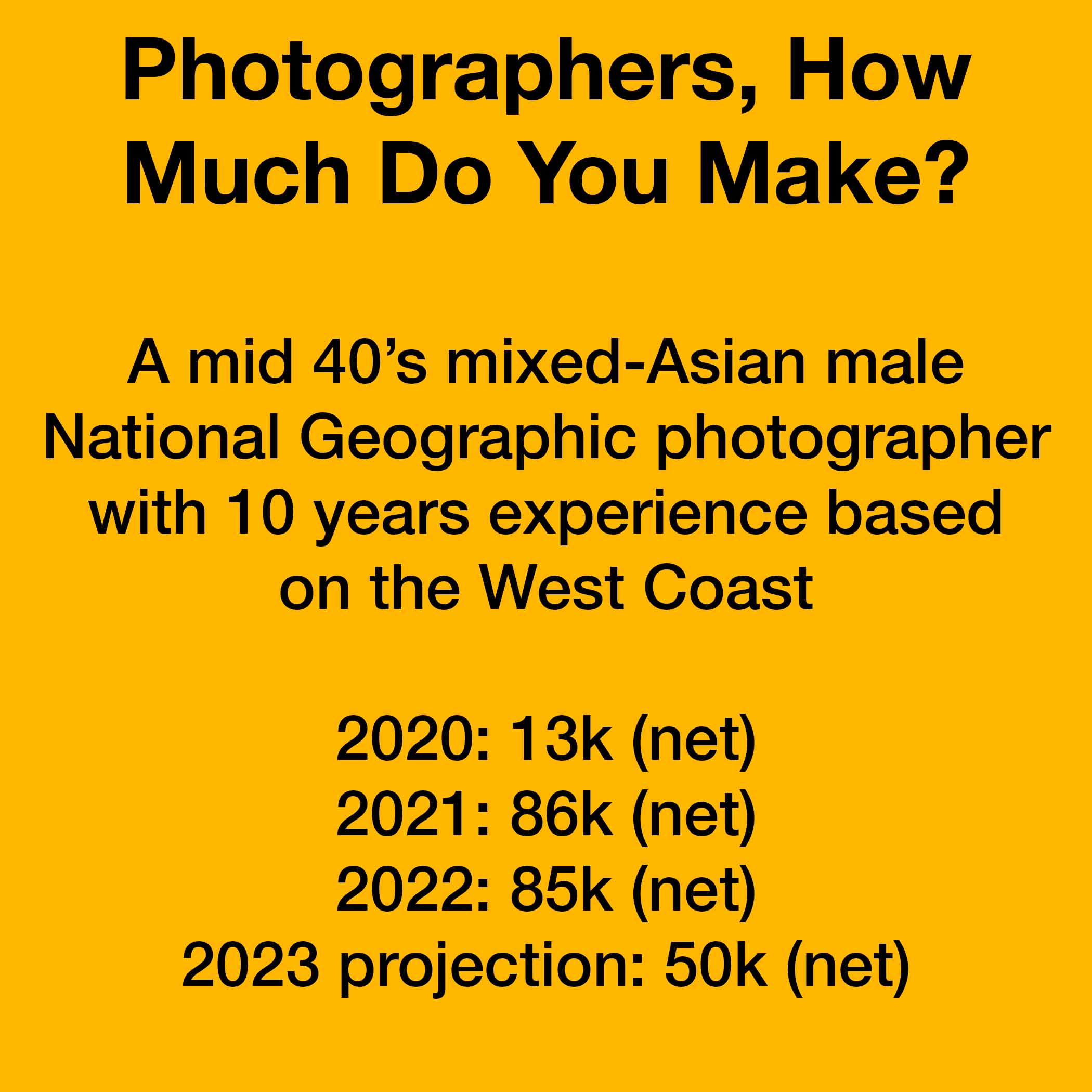

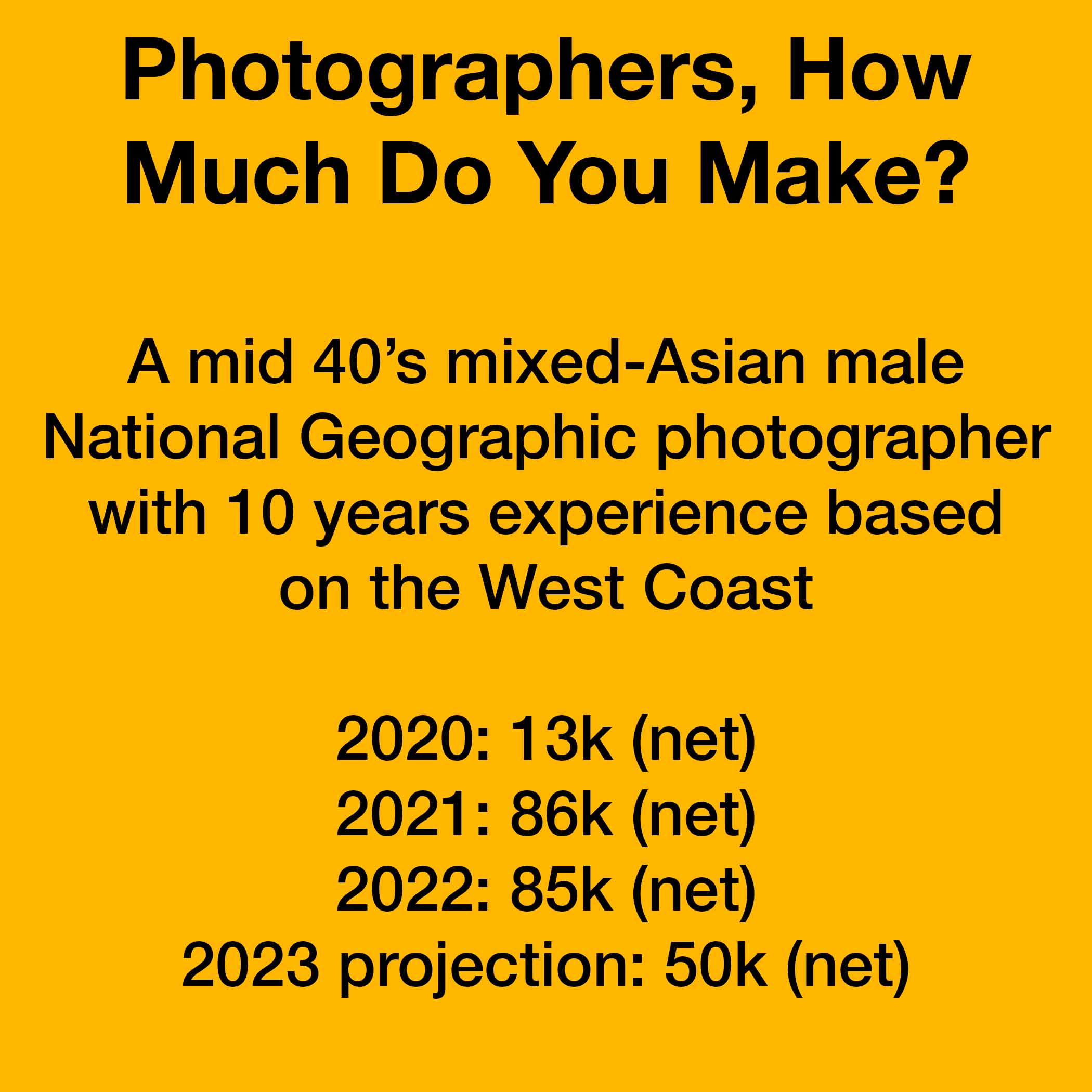

I’m a Editorial, Documentary, Culture, Wildlife, Landscape, Underwater and Travel photographer whose income is 40% from NatGeo Editorial or Grant, 50% from NatGeo Brand Partnerships, and 10% NatGeo Expeditions, Fine Art sales, and Speaking fees.

I have 10 years experience but only the last 4 were exclusively photography.

My overhead is high.

Underwater camera and diving equip- approx 20k/yr

Wildlife specific equipment- approx 10k/yr

Arctic and expedition specific gear- approx 2.5k/yr

My profit margin varies- 30%-60% dependent on grants vs commercial budget.

I work 330 days a year with approximately 280 in the field. National Geographic Magazine – all editorial, long-form multiyear projects, typically 250 days in the field annually. National Geographic Brand Partnerships- on-camera talent, Social Media photo/video, typically 30 days annually.

The last few years my income has been highly variable depending on number of NatGeo commercial brand partnerships, random fine art/nft sales.

For the first 6 years, I also ran a second business making 40k/yr to stay afloat. This career would have been impossible otherwise.

Average National Geographic magazine assignment is 2 years long with a day rate of $650 (now $775), in theory after expenses, but I am aways working many additional assignment days off-record to ensure the quality of the story and images. A better look at the average take-home is amount of income made on grant funding which comes out to about $250/day in the field.

Average brand partnership job is 5 days at $4k/day after expenses.

My best recent job was 9 days with travel, plus 3 days edit/post which brought home $90,000 after expenses. This was for on-camera talent, still photography, and some writing.

Worst paying jobs are grant funded projects for 240 days at around $250/day in the field, $210/day if editing/captioning included (worst but also typical).

I used to do video just for social but it’s now a regular ask as part of the regular job.

The best advice I have received is that it will take longer than you think to succeed in this industry, so make long-term decisions and plan for 5 years before making a living. And to work on personal projects and fund them yourself.

I don’t do any marketing, just the occasional contest entry.

My retirement plan is to work until I die… but seriously I save about everything I don’t invest back into the business.I have few personal expenses because I am always working.

Having a successful long-term career in photojournalism or documentary is difficult. You have to want to be a journalist and be passionate about the good that it can do more than anything else in life.

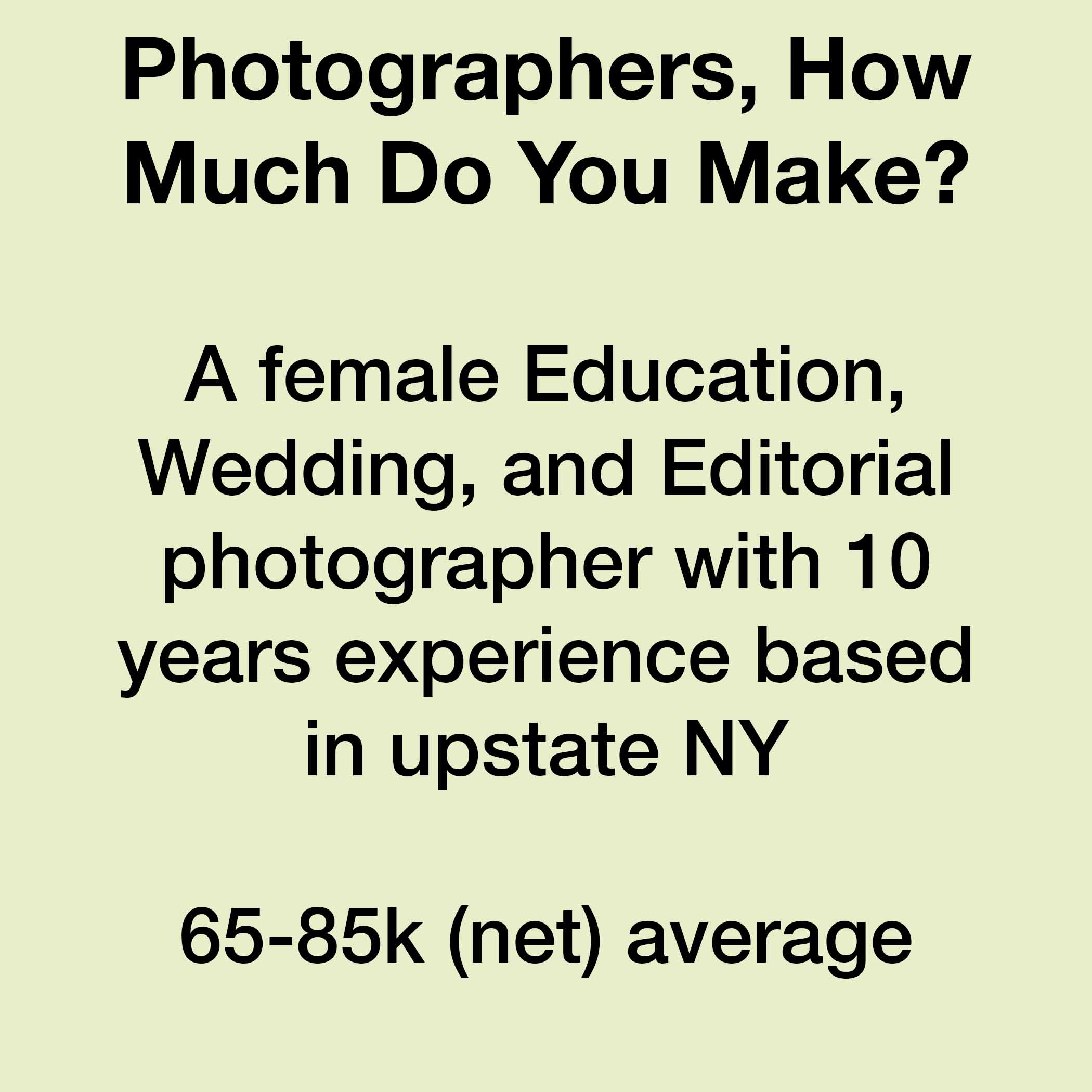

My income is 40% education, 50% wedding, 10% editorial

My clients are Ivy league institutions, plus some small businesses, niche publications, and down-to-earth wedding clients with mid-range budgets.

I have minimal business expenses. I save 22% of every check for taxes, 15% for retirement savings, and 6% for business expenses. So I’m taking home about 57% of my annual gross income.

I work about 150 days a year… 2-3 days / week for my photography business.

My inquiries and workload dropped significantly in 2020 because of COVID, but I was also raising my rates and changing work style, so my income didn’t drop much. I’ve been able to work far fewer hours (I work an average of 10-25 hours / week on my photography business) but maintain the same annual income as I had pre-COVID when I was working almost full-time.

I also do project management for creative studios. I genuinely love this work, it’s not just filler. And it allows me to only do the kind of photography work that I really love. This work is not included in $$ range I quoted above.

Average academic shoot: 6 hours on campus photographing classrooms & research groups in action, some portraits. $300/hour of photography time works out to an $1800 day. I don’t have any shoot-specific expenses (I work alone and I don’t often rent supplemental equipment). This comes with a non-transferable, non-exclusive license for the department or school that I’m working with, though the university is gathering the releases so I don’t have explicit permission to resell except within the university community (which does actually happen frequently).

Average wedding shoot: 8 hours on location, no second photographer. $5,400. +$2k if they want a second photographer. Delivery in an online gallery within 3-6 weeks, digital downloads included, prints and albums at additional cost. If I’ve hired a second photographer, I typically pay $600-800 for the day. Otherwise no shoot-specific expenses.

If we’re talking about best ROI in terms of time, it’s weddings. But outside of that realm, I had an editorial shoot for an alumni magazine that paid $2k, which included features in interior spreads and on the cover. An alumni class president saw the cover image and purchased 150 mounted prints of the photo for the class reunion, which netted me another $7k. Another great ROI in terms of time spent.

I photographed a cookbook with a net of about $10k. I had just had a baby and was otherwise not working, but the cookbook was written by moms and for families, so they were so accommodating and cool with me bringing baby along to many of our shoots. The book focuses on seasonal recipes, so I did 10 days of shooting spread out over a whole calendar year, plus LOTS of coordination, planning, and collaborative editing. The work really speaks to my values and style, but financially it wasn’t a great return on my time.

I don’t shoot video.

I live in a small city where I’m one of the highest paid local photographers in terms of hourly and day rates. I don’t aspire to work outside of my geographic region (I value the work/life balance I’ve been able to build with my young family) so I feel pretty much capped out in terms of raising my rates. But it works for me.

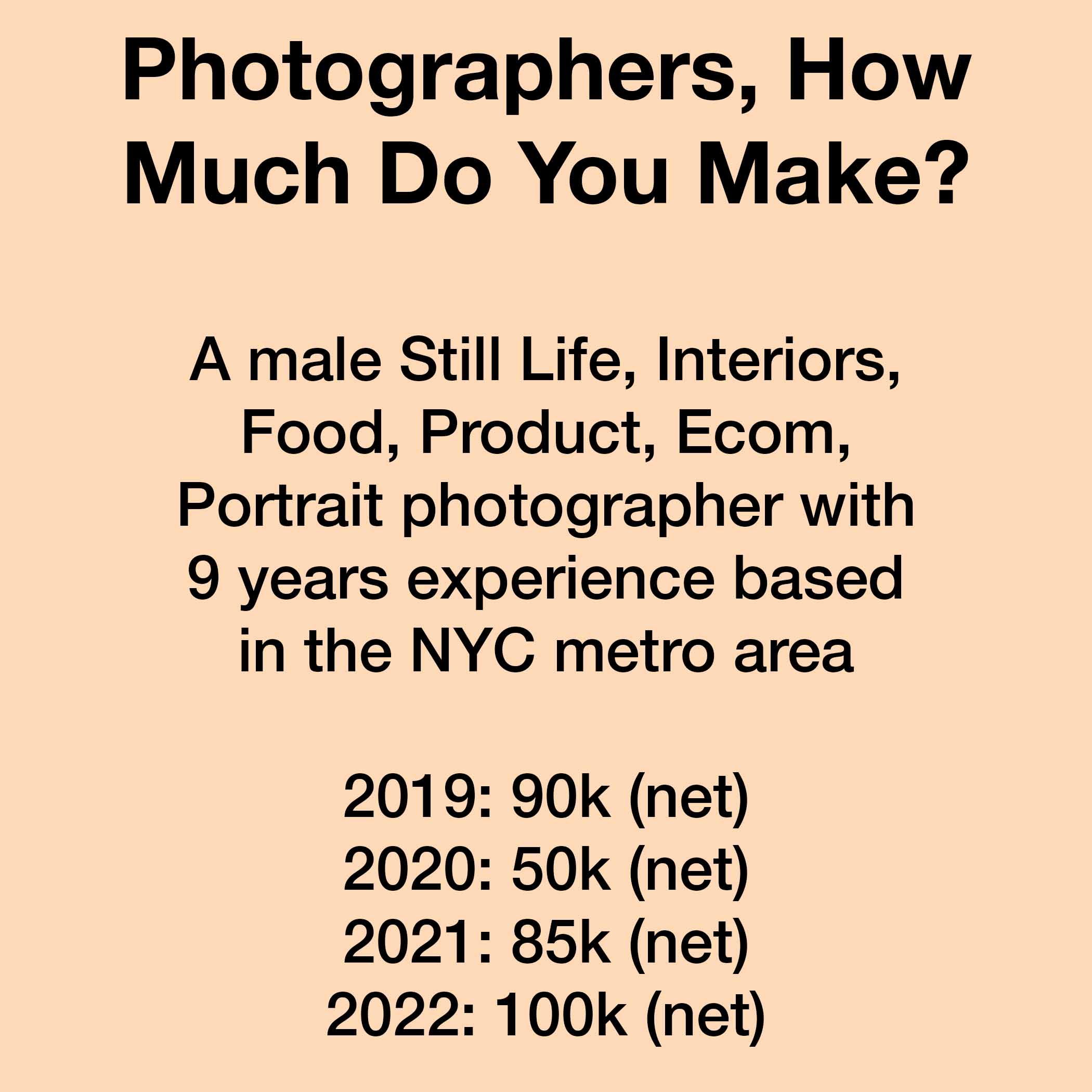

My income is 20% interiors and food from restaurants with a social media presence, 20% from Ecom where I travel to a studio or shoot at my home studio, 40% from a perma-lance 3 day a week gig where I shoot social media beauty images. 20% from one off clients (medical clients… interiors and some portraits, headshots for bands and actors, etc …).

My clients are small to medium and local. Small e-commerce companies, large fashion brands, start ups, independent architects and interiors designers, medical, restaurants, bars, fragrance, beauty.

I use freelance assistants and retouchers, and freelance consultants to help with marketing (how to contact new clients, what images to put in my emails and mailers).

My main overhead is equipment, I’m always needing another few pieces to keep up, sometimes I get to rent them back to myself for shoots and that helps cover the cost. Spent 7k on equipment in 2022 (I also bought a drone and became licensed) I have a home studio so I don’t count that as overhead. Maybe spend 2k on marketing every year (mailers, consultant, social media ads).

My profit margin pre tax is 90%.

I work 4 days a week most of the time.

I went from a staff full time photographer (7 years paid salary bi-weekly), to a freelance photographer when I was laid off March 2020 (Covid). I’ve always wanted to be independent and that time helped me pivot. I have 4 consistent clients every year that make up 60% of my income, assisting and teching is 10%, other clients 30%

I average 3 days every week 9-5 $1200 a week. Ecom work is usually 9-3 @ $500-$1000 day rate sometimes I travel to a studio, sometimes the client sends me samples and I shoot and retouch at home so I can work as needed. My food and interiors work can vary greatly but on average $1200 as a day rate, have to travel with gear, set up, and break down in 8 hours and I do a 1/2 day of editing for these. Bigger shoots I usually clear $3000-$5000 and have a day of shooting with usually two days of editing after. I’ve also started to assist other photographers and teching with my gear that added about $10k last year.

My best shoot last year was a $3500 day rate and $3500 for licensing, I also rented my own equipment, and charged an hourly production fee rather than hire a producer. This took 3 full days to edit and another 2 days to produce, but I had zero overheard and made some money back on equipment purchases. Client paid the crew separately. This would be an ideal way of working but I can’t seem to get more than a couple of these every year.

My worst was shooting Ecom for $350 a day for 8 hour days, plus I had to pay for $20 for parking, $20 for tolls, 2 hours of commuting and work in storage warehouse all day. Sometimes I got a window to look out.

I do some stop motion but no video yet.

I think owning my own gear and having my own space for shoots has been huge in my work. I sometimes go weeks without a day off, and sometimes weeks without having any gigs. I feel like my breadth hurts my brand for bigger clients but it also opens myself up to more smaller clients. My goals are to learn more about the business of photography. I’m just starting to learn about licensing and how I’ve let people over use my work in the past. I feel like I can create with the best, but I can’t seem to reach my target clients, and when I do I have trouble landing the gig because I don’t know how to close the client.