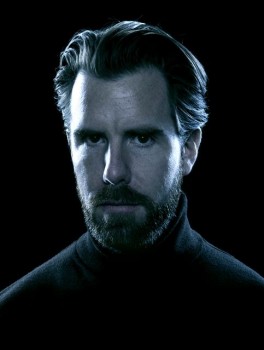

I first met Darius at Review Santa Fe many years ago when he was the editor of Photo-Eye Booklist, the quarterly, highly collectible catalog of books for the renowned local photography bookstore. When I heard several months ago that he’d founded a photography book publishing company called Radius Books (website here) I was curious to find out more on how the book publishing side of this industry works.

I first met Darius at Review Santa Fe many years ago when he was the editor of Photo-Eye Booklist, the quarterly, highly collectible catalog of books for the renowned local photography bookstore. When I heard several months ago that he’d founded a photography book publishing company called Radius Books (website here) I was curious to find out more on how the book publishing side of this industry works.

Tell me a little bit of your background.

My education history and work history are basically interrelated and flow one into the other. I received a BFA in Photography at ASU, Tempe back in the early 90s and then went overseas where I worked for an organization that had a large, permanent collection of historical photographs, which dated back to the 1870s. While there, I pursued my own photography and got called upon to do everything from photograph visiting prime ministers to documenting deteriorating historical buildings.

I came to Santa Fe in 1998 to pursue a Master’s degree at St. John’s College, which, as you know, has a Great Books program. On the surface, it may seem to have nothing to do with a career in the arts, but to me it brought intellectual balance to an undergraduate fine arts degree. At the heart of the program are a couple concepts that I gravitated to. One is the idea of books serving a centuries-old dialogue about core ideas that affect humanity, regardless of race, culture, language, or class. Another was a cluster of ideas about the role of the arts in society and where image-making, artists, language, communication, and what it means to be human all figure in.

I came to Santa Fe in 1998 to pursue a Master’s degree at St. John’s College, which, as you know, has a Great Books program. On the surface, it may seem to have nothing to do with a career in the arts, but to me it brought intellectual balance to an undergraduate fine arts degree. At the heart of the program are a couple concepts that I gravitated to. One is the idea of books serving a centuries-old dialogue about core ideas that affect humanity, regardless of race, culture, language, or class. Another was a cluster of ideas about the role of the arts in society and where image-making, artists, language, communication, and what it means to be human all figure in.

During my time in graduate school, I began working at photo-eye part-time, in the bookstore. I stayed on after graduation to launch the magazine, which was a quarterly devoted to photography books. It was here that my love of photography and a latent but deep-seated love for books–as art objects as well as conveyors of ideas and images–merged.

So, I guess you spent so much time looking at photography books working on booklist for Photo Eye you decided it looked pretty easy and you’d start your own imprint. Isn’t the photography book business notoriously unprofitable? Doesn’t that frighten you?

There was always a paradox floating around out there that didn’t make sense to me. The illustrated art book business was notorious for being unprofitable, true, but each year as editor at photo-eye, I was dealing with more and more publishers coming onto the scene that were producing great books. The two didn’t jive for me. There was a great article written by Christopher Lyon in Art in America in September, 2006 which gave a key to understanding this bigger picture. The large, illustrated book publishers (think Prestel, Rizzoli, Harry N. Abrams, Bulfinch) simply weren’t able to sell tens of thousands of copies of fine art books to the masses the way they used to. So their world was changing drastically, and Lyon detailed how and why in that article. But similar to the music industry,

There was always a paradox floating around out there that didn’t make sense to me. The illustrated art book business was notorious for being unprofitable, true, but each year as editor at photo-eye, I was dealing with more and more publishers coming onto the scene that were producing great books. The two didn’t jive for me. There was a great article written by Christopher Lyon in Art in America in September, 2006 which gave a key to understanding this bigger picture. The large, illustrated book publishers (think Prestel, Rizzoli, Harry N. Abrams, Bulfinch) simply weren’t able to sell tens of thousands of copies of fine art books to the masses the way they used to. So their world was changing drastically, and Lyon detailed how and why in that article. But similar to the music industry,  where genres were reproducing and splitting and creating sub-categories faster than bunnies, the art and photography book scene had become filled with lots of nimble, savvy, smaller publishers who had very smart, sophisticated collectors buying their books. If you don’t have to maintain office space on Madison Ave and you’ve got a staff of 1 to 3, you don’t need to sell 25,000 copies of each title. As people like Jack Woody of Twin Palms Publishers or Chris Pichler of Nazraeli Press proved, you can sell 1000 or 2000 copies of a book, watch it go out of print in a couple years, recouping your costs in the meantime and move on to the next list of projects.

where genres were reproducing and splitting and creating sub-categories faster than bunnies, the art and photography book scene had become filled with lots of nimble, savvy, smaller publishers who had very smart, sophisticated collectors buying their books. If you don’t have to maintain office space on Madison Ave and you’ve got a staff of 1 to 3, you don’t need to sell 25,000 copies of each title. As people like Jack Woody of Twin Palms Publishers or Chris Pichler of Nazraeli Press proved, you can sell 1000 or 2000 copies of a book, watch it go out of print in a couple years, recouping your costs in the meantime and move on to the next list of projects.

It’s definitely not easy. But loving what you do helps (and being small and nimble is an asset).

Seems like portfolio reviews like the one in Santa Fe where you live are a great place to find projects to publish. Alec Soth was discovered there and I’m sure there were many others that got started that way. Is that your primary source for finding a book project?

Actually, they’re not the primary source for finding a book project, but they are a piece of the bigger picture. Portfolio review events are a primary way of staying in touch with the photography community overall. We, meaning publishers, editors, gallerists, dealers, collectors, curators and writers like to see and know what photographers are up to, what they’re working on, where their traveling, who they’re shooting for, and where they’re showing their work. Signing up a photographer on the spot at a portfolio review event happens more with galleries than it does with publishers, but things happen afterwards, and seeing people at these portfolio events is important.

What are the big considerations when looking at a photographer for a book? How much of a factor is potential commercial success?

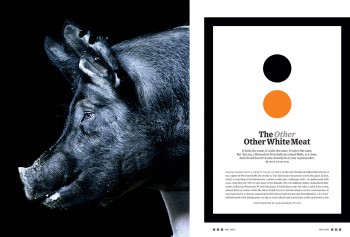

First and foremost on the list is that we are deeply moved by the work and think that it is important in some lasting way. We’ve got two photography books on our Fall 2008 list. One is a book of brilliant photographs made in New Mexico by Lee Friedlander. The other is a lyrical group of photographs by Phoenix-based photographer Michael Lundgren. In terms of their careers, they couldn’t be further apart from each other. Friedlander is, well, Friedlander. How do you even summarize his influence on photography as a medium?

First and foremost on the list is that we are deeply moved by the work and think that it is important in some lasting way. We’ve got two photography books on our Fall 2008 list. One is a book of brilliant photographs made in New Mexico by Lee Friedlander. The other is a lyrical group of photographs by Phoenix-based photographer Michael Lundgren. In terms of their careers, they couldn’t be further apart from each other. Friedlander is, well, Friedlander. How do you even summarize his influence on photography as a medium?  Lundgren is a couple years out of grad school and passionate about his work and makes stunning prints based on an intelligent and soulful approach to the landscape but virtually no one has heard of him. No one, apart from the lovely Rebecca Solnit, who is contributing a wonderful essay, which will help bring attention to the work. If we looked at Mike’s book purely from a commercial standpoint, we probably wouldn’t publish it. But we love the work and are publishing a modest number of copies, which will be supported by a limited edition book which comes with a print. And we’re extremely proud to be one of the first to commit to this relatively young artist with a strong vision.

Lundgren is a couple years out of grad school and passionate about his work and makes stunning prints based on an intelligent and soulful approach to the landscape but virtually no one has heard of him. No one, apart from the lovely Rebecca Solnit, who is contributing a wonderful essay, which will help bring attention to the work. If we looked at Mike’s book purely from a commercial standpoint, we probably wouldn’t publish it. But we love the work and are publishing a modest number of copies, which will be supported by a limited edition book which comes with a print. And we’re extremely proud to be one of the first to commit to this relatively young artist with a strong vision.

Defining “commercial success” is different for each publisher. Again, it’s tied in to how many mouths you have to feed. Being a small publisher brings certain advantages and nimbleness that are inherently different than the advantages of being a really big publishing house.

Do you think that books will continue to be a hot ticket for collectors and photography lovers? Are there any cool innovations coming that can keep this market growing?

I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t think books were important, and therefore worth saving and cherishing and collecting. The market for the book-as-object is getting more firmly established every passing auction season. And more and more artists, not just photographers, are seeing the book as a central means of expression. Concurrently, more and more curators and galleries are seeing books as a central means of expression, and are collecting accordingly. For instance Charlotte Cotton, curator and head of the photography department at LACMA recently purchased an entire set of prints by Paul Graham that make up one of his twelve volumes in A Shimmer of Possibility, which was published by Steidl last Fall.

I wouldn’t be doing this if I didn’t think books were important, and therefore worth saving and cherishing and collecting. The market for the book-as-object is getting more firmly established every passing auction season. And more and more artists, not just photographers, are seeing the book as a central means of expression. Concurrently, more and more curators and galleries are seeing books as a central means of expression, and are collecting accordingly. For instance Charlotte Cotton, curator and head of the photography department at LACMA recently purchased an entire set of prints by Paul Graham that make up one of his twelve volumes in A Shimmer of Possibility, which was published by Steidl last Fall.

What will keep the market growing are artists engaging with the book in this manner, where the book is seen as more than just a repository for images, but rather the seat of artistic expression. And then persuading collectors to buy them. Honestly, this is where I see the role of curators, critics/writers, and publishers. We have the chance to guide others–the public, the collectors, the institutions–to work that will have lasting importance, explaining why along the way. At least, that’s how I see my role as writer and publisher (and I know that my partners at Radius Books feel the same way). I get excited about work and I want to show others and elucidate how I see this work fitting into a broad and rich cultural dialogue.

I see the role of curators, critics/writers, and publishers. We have the chance to guide others–the public, the collectors, the institutions–to work that will have lasting importance, explaining why along the way. At least, that’s how I see my role as writer and publisher (and I know that my partners at Radius Books feel the same way). I get excited about work and I want to show others and elucidate how I see this work fitting into a broad and rich cultural dialogue.  That’s the St. John’s influence speaking! One thing we’re excited about at Radius is the implementation of our library donation program–over 200 copies of every book we publish is being donated to libraries across North America in an effort to further the dialogue surrounding great art. We’ve got a strong group of donors that are helping this happen (though we’re looking for more to assist) and they are very excited about the role the book can play in stimulating dialogue.

That’s the St. John’s influence speaking! One thing we’re excited about at Radius is the implementation of our library donation program–over 200 copies of every book we publish is being donated to libraries across North America in an effort to further the dialogue surrounding great art. We’ve got a strong group of donors that are helping this happen (though we’re looking for more to assist) and they are very excited about the role the book can play in stimulating dialogue.

What do you think of these self published solutions like Blurb? Will they ever compete with the traditional book publishers for market share?

I love them. I think they demystify the process of publishing a book, on a certain level. Print-on-demand won’t replace traditional publishers, but it can supplement them in important ways. It’s like having another tool in the toolbox for artists and photographers. Not sure what your current edit looks like in book form or want to try two or three sequences? Do a Blurb book (or two or three)! Not sure what the ideal trim size is for the book that’s in your mind’s eye, or not sure how long that essay will be on the page? Do a Blurb book! Going to a portfolio review event and want something really well done to give to your five favorite galleries? Do a Blurb book!

Blurb is hosting Photography Book Now, an open competition that ends in mid-July, and I’m involved with both the judging process (which I’m very excited about) as well as the traveling symposium that will take place in San Francisco, London and New York this Fall. One of things that we’re aiming to do with the symposium is to crack the door to what happens at publishing houses. Doing a Blurb book is a little like DIY publishing, right? We want the symposium to give you insight on the role of a good editor, how designers approach text and image combinations, how other book artists are using the book as object, etc.

Through the contest, we’re hopeful that the cream of the crop will rise to the top. We know there are photographers out there who think in terms of book-length projects and who simply haven’t had a chance to get that work in front of people in the photography industry. This is their chance.