Sorry, I was wrong.

I don’t have one submission left from 2020, but three. (Well, two after today.)

As you know, I review exhibitions, write about photography festivals, and share travel stories throughout the year, so I’m not able to get through my book stack as quickly as I’d like.

We’re fortunate that artists keep sending books in, for my perusal, but it means occasionally a book will linger here, in the stack, and for that I apologize.

Therefore, while I mix in tales from Chicago, (the trip was awesome,) I’ve decided the next books I review will be the ones that came in last year.

(It’s time.)

Today, though, we’ll be looking at a submission I purposely sat on, as I wasn’t ready to write about it until now.

As I got home after Midnight Monday morning, and have been going non-stop ever since, I hope you’ll allow me a more direct, less metaphorical transition.

There’s an English expression I like, where they just say two words: “Needs must.”

So there we are.

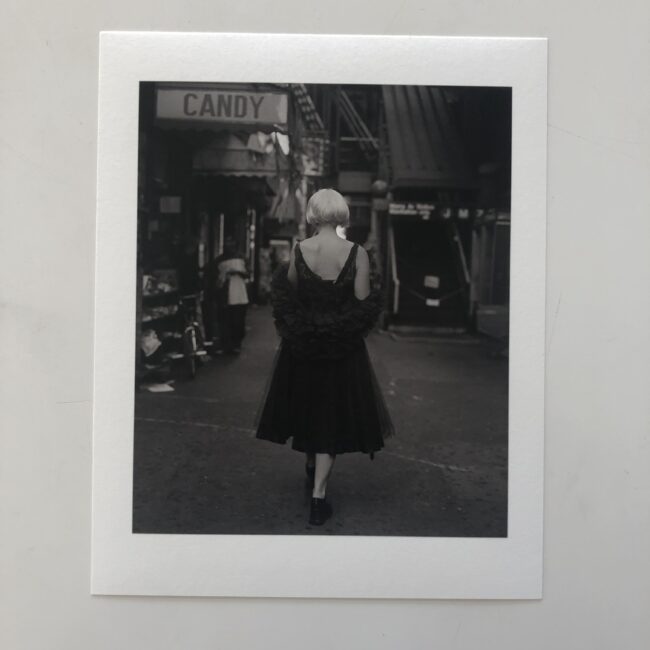

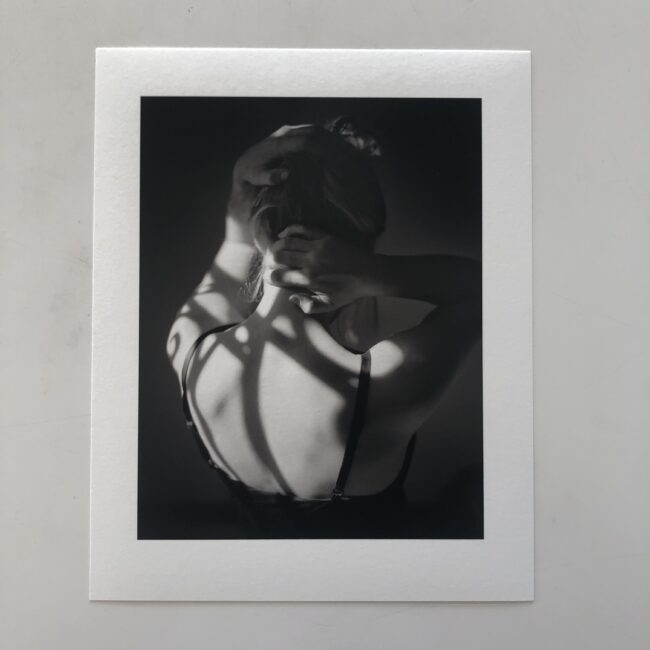

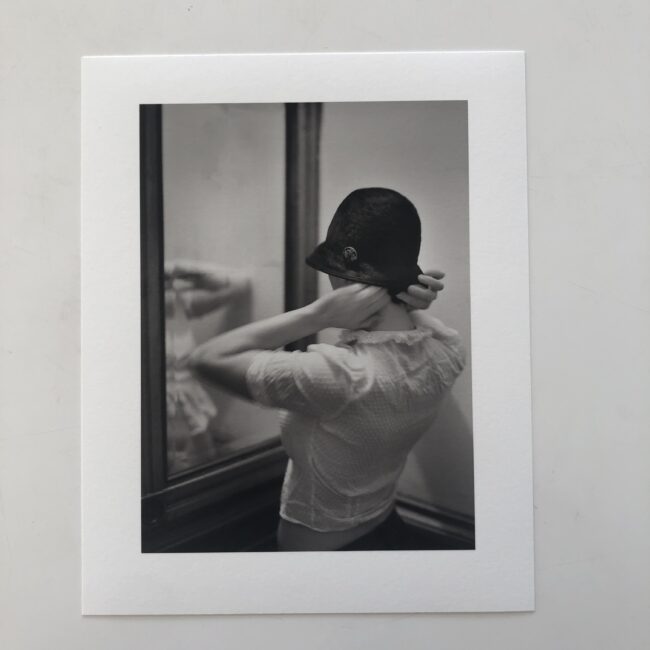

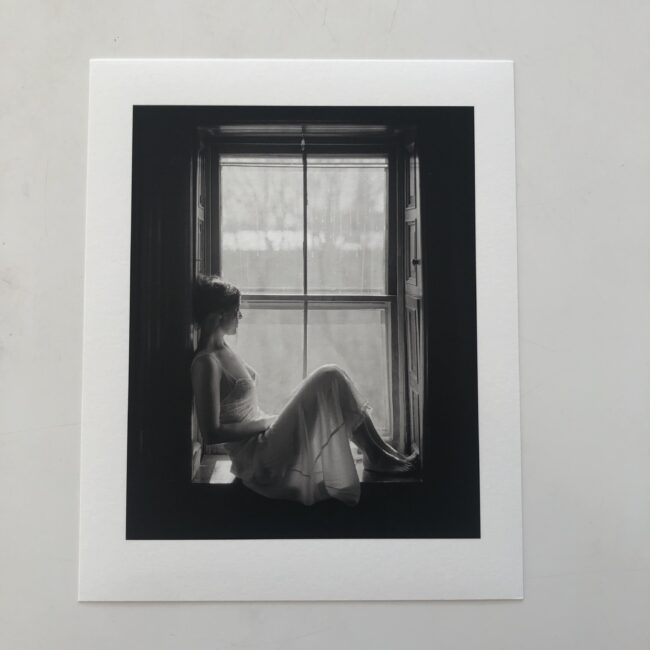

I reviewed a book by Portland artist Jason Langer years ago, and we remained in touch. I was enamored of his “timeless” style, as he often makes black and white photographs that appear conjured from the 19th Century.

It’s a “look,” I suppose, and of course removing 21st Century temporal artifacts helps as well.

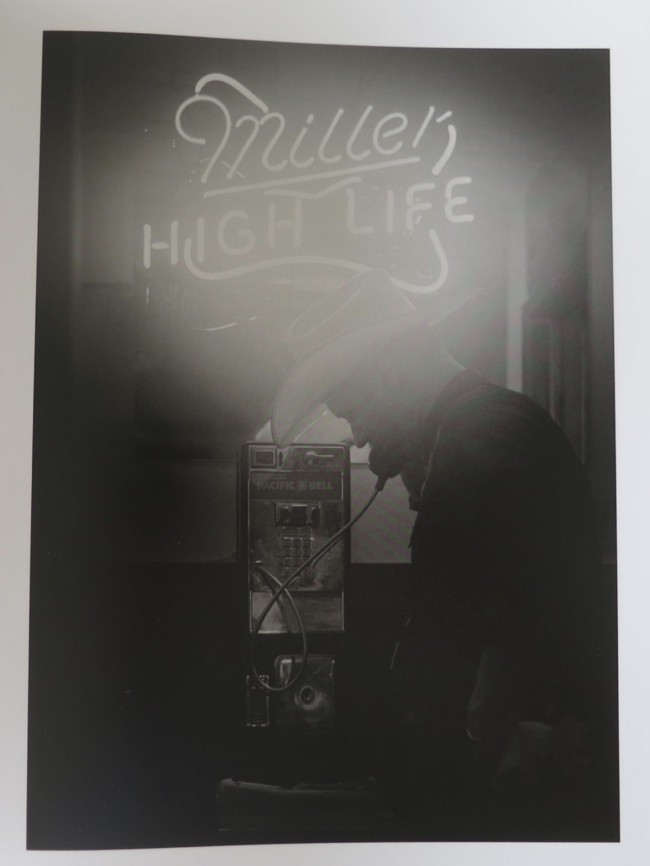

Sometimes, even when the details are current, (or end of the 20th Century,) they still feel ripped from the space-time continuum, as I vividly recall an image he took of a cowboy at a payphone in a bar in San Francisco, and it stuck in my memory banks.

Payphones?

Kids today don’t even know what the hell those are. (Just ask Eric Kunsman, he’ll tell you.)

But back in the summer of 2020, I wrote an article discussing male photographers, and the power dynamic imbalance when they photograph naked women, after stumbling upon an almost soft-core-porn Instagram account.

(I’m rarely naive, but really, I had no idea those things are out there.)

Whether it was via email or Facebook, I can’t recall, but Jason, who’s photographed nude men and women for years, reached out, saying he thought it was a far-more-nuanced conversation, and could he send me something that might open my mind a bit?

I said “Sure,” because that’s how I roll.

And here we are.

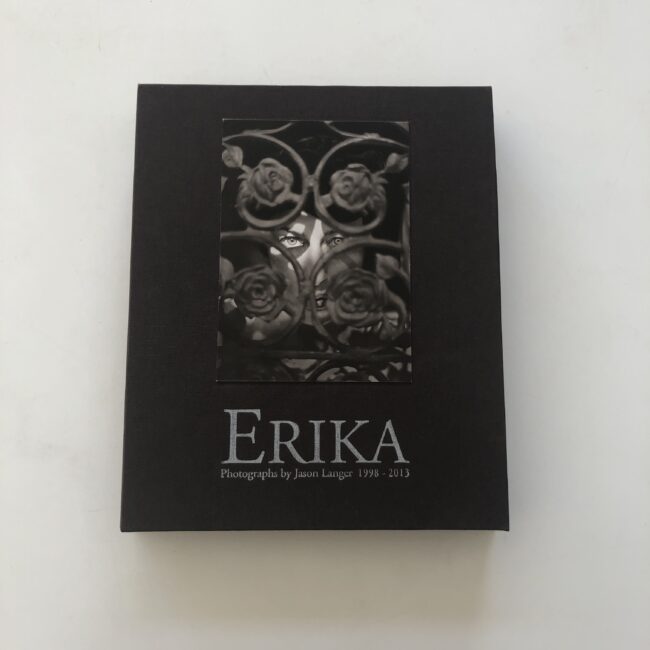

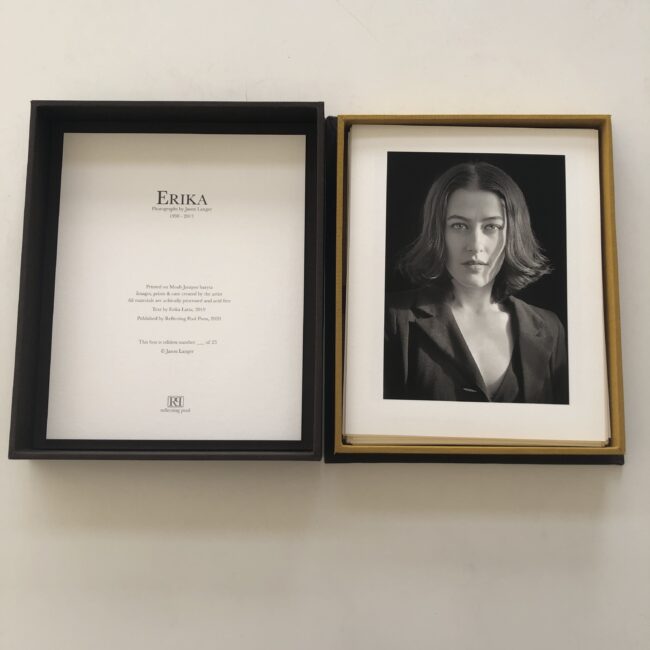

“Erika,” published by Reflecting Pool Editions, is not a traditional book, by any means, which Jason acknowledged in the letter that was taped to the brown-paper-wrapped offering.

Frankly, it looks like a portfolio of loose images, brought together in a fancy box, and if that’s how you see it, I won’t argue.

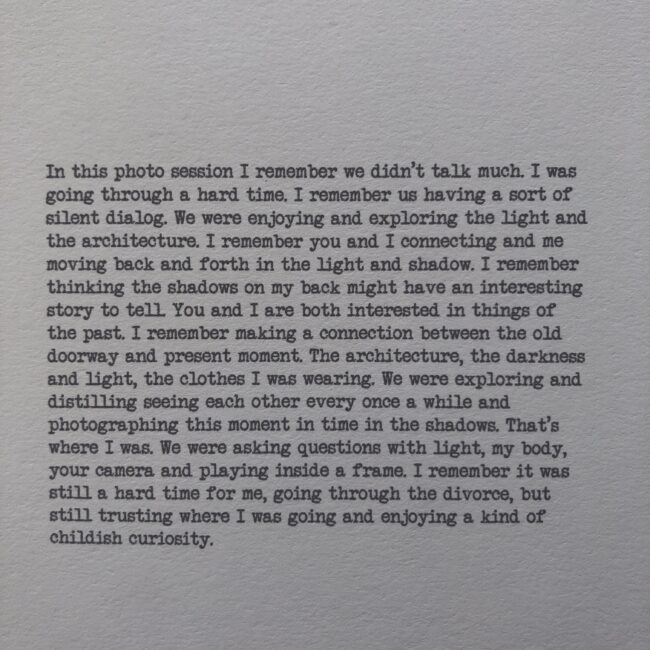

But experientially, it’s a book, as the narrative unspools over time, (15 years,) via multiple photo shoots the artist undertook with Erika, his muse.

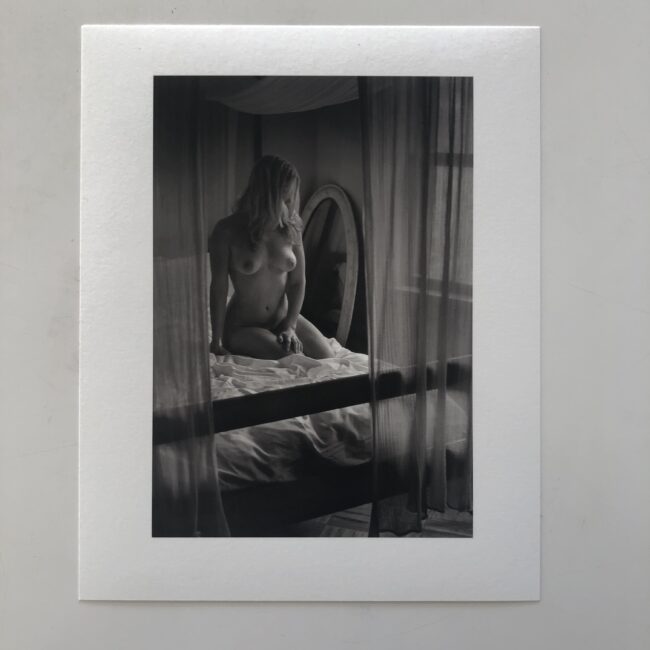

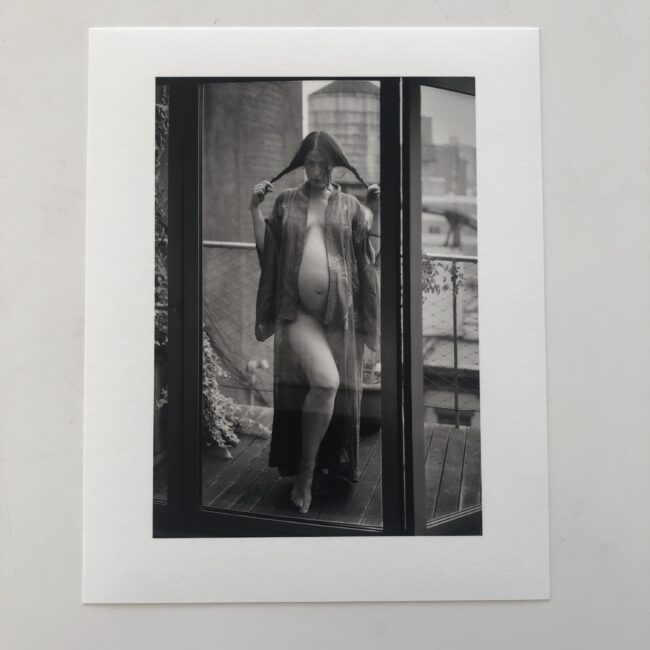

To begin with, there are only a few “nude” images in the book, but I held off looking at it until today, as I was afraid it would be more graphic than that, and we’ve avoided publishing nudity for many years now. (Rob gave me permission to include a couple of the photos, but really, it’s a small percentage of what’s in the box.)

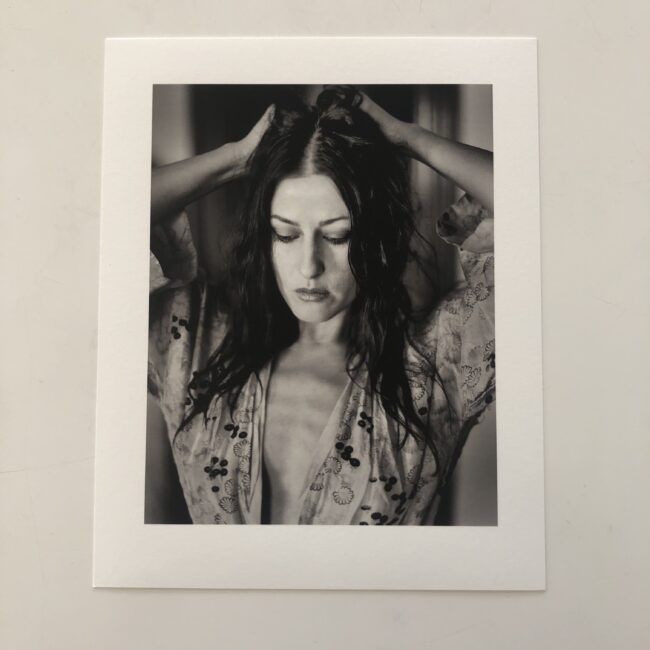

Erika, who is obviously beautiful, is an actor, writer, director, producer and photographer, who made a career working in experimental theater, both in the US and around the world.

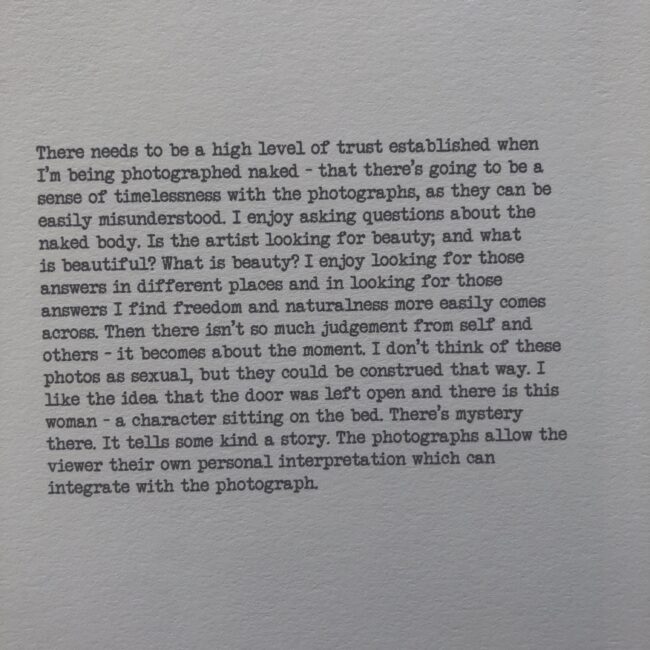

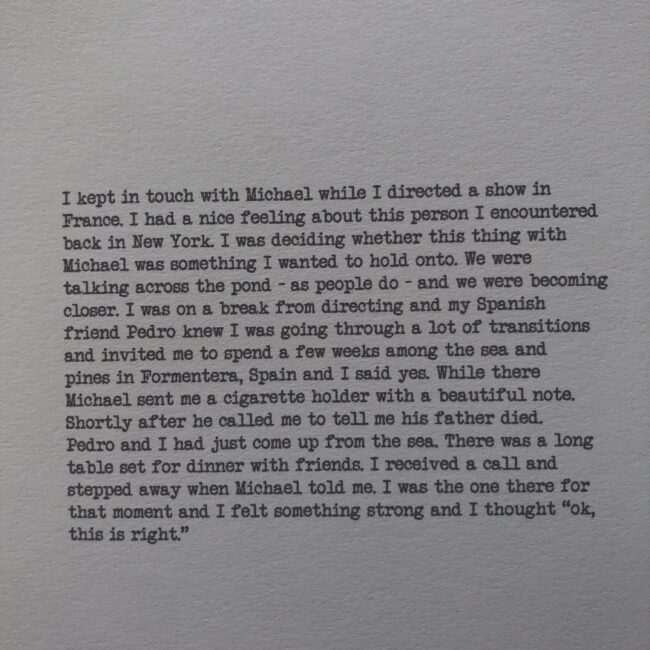

Each photograph includes a piece of her writing, printed on the back, and we learn from Jason’s ending essay the text comes from a series of interviews they conducted in 2019.

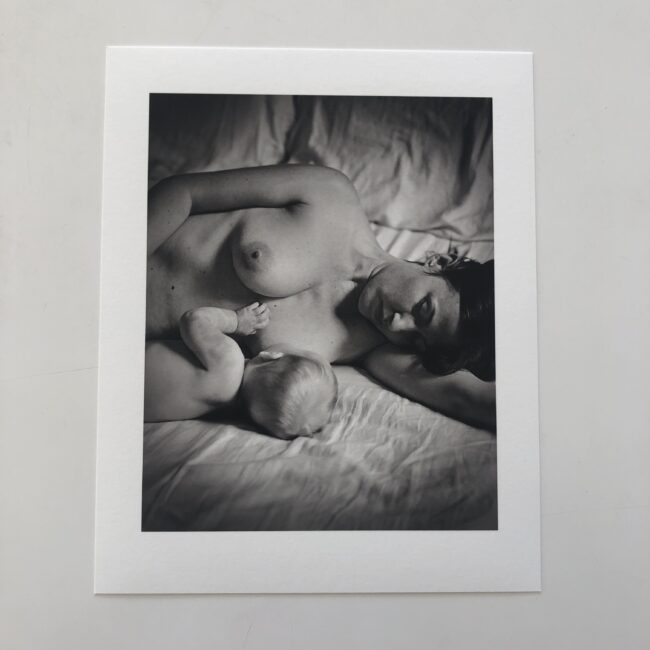

These are current reminisces, looking back at New York in the 90’s, her past relationships, and what it meant to become a mother.

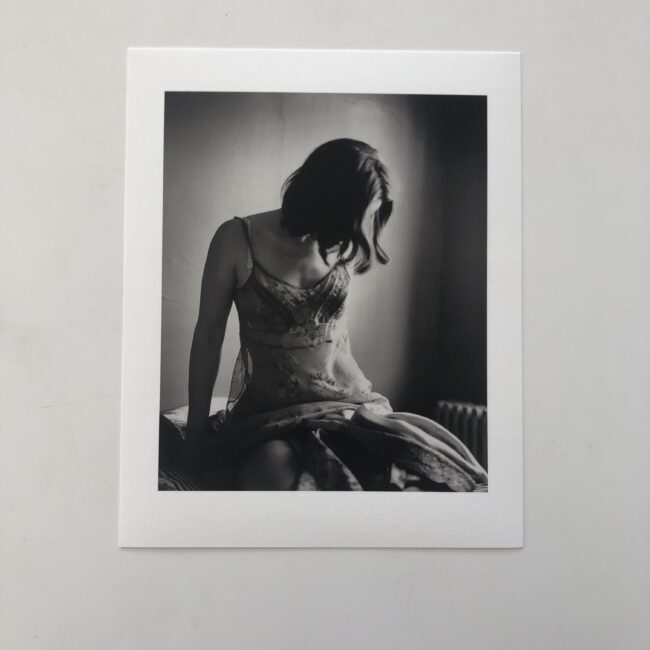

Certainly, some of the images fit with Jason’s style of stepping out of time, but to me, that’s not really what this book is about.

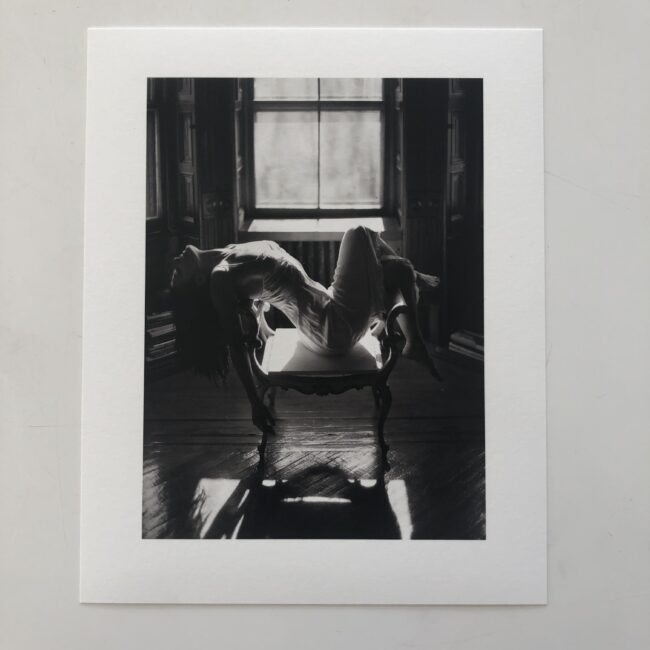

Rather, it makes me think of agency, and collaboration, as when I wrote about men exploiting women last year, Jason, and one photographer with whom I traded off-the-record IG DM’s, both said many models love the work, and feel empowered by doing so.

(Foreshadowing here, but I saw some nude art in Chicago that gave me the creeps, as it so clearly fit with my sense of men commodifying women.)

But this doesn’t.

Erika is a performer, and in some images, you can feel her embodying a character.

She knows how to present herself, and there was no part of my viewing experience in which I felt she was an object.

As you read her thoughts, and the stories of working in Europe, having love affairs, living the artist’s life in rapidly gentrifying New York, it’s clear Erika is a powerful, intelligent, talented, confident woman.

She and Jason grew together, over time, which he confirms in his ending statement.

Working with Erika opened up his feminine side, and helped him push his photographic career forward.

At some point, over the last five years or so, commenting on someone’s appearance became verboten.

It’s not PC to call a women beautiful, outside of a very strict set of parameters, but certainly not in any professional setting.

I get it, and have no beef with that at all.

But you can’t look at a book like this without understanding Erika is lovely, she knows it, and as a performer, her face, mind and body are her tools of expression.

I’m still not sure I understand why it’s necessary for her to take her clothes off, but perhaps the prevalence of pornographic imagery in the 21C has skewed our cultural sense that the human form can ever be anything but sexualized.

(Certainly here in America.)

After looking at this book, though, I accept that if two collaborating artists, exploring the world, choose to make art this way, it’s not right for me to dismiss it out-of-hand.

Especially when it results in something I found captivating, enriching, and thought-provoking.

If you choose to disagree, that’s totally cool.

It’s still a free country, after all.

(At least until 2024, when all hell breaks loose.)

To learn more about Erika, please click here

Please be advised, two of the images below feature nudity.

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are particularly interested in books by artists of color, and female photographers, so we may maintain a balanced program. And please be advised, we currently have a backlog of books for review.

1 Comment

First, I agree the work is lovely, the subject is lovely-to-me, and that it is a better example of how one can handle a woman as subject, even in sensual ways, and produce work with depth and layers of meaning. Second, I find the whole topic spectrum of women in photography fascinating. Women as subject. Women as photographers. Women as critics. Women as curators. And what I find particularly intriguing is women photographing women nude. As a heterosexual male, I find it impossible not to initially sexualize a woman that is attractive-to-me. The artist statements of women photographers presenting themselves or other women in the nude often claim to be seizing control of how their bodies are viewed, but, the sight of an attractive-to-me woman in the nude or sensually posed always engages my libido first. Even in the series of photographs you present here, this happened. So, there is the problem. We are hardwired to be attentive to sexuality as our first response to human beings we encounter. I see no way around acknowledging this and then finding a positive way of dealing with it and moving beyond. What I have begun to try to do is to acknowledge this initial lust-feeling to myself, but let it pass through like clouds in the sky, as we are told to do in meditation practices, so that I can move on to a fuller appreciation of the work or person in front of me.

Comments are closed for this article!