My neighbor built a heliport, about five years ago.

He didn’t have the permits to build in a remote, rural valley, but he’s a wealthy man, so he skirted the rules, and got away with it.

(Like that phrase, it’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission.)

Sure, some people made a fuss, but as he built across the street from the volunteer firehouse, and enlisted some of the firemen to walk around with petitions, there was at least plausible deniability.

(That it was in the public interest.)

Ironically, my neighbor does not own a helicopter, (that I’m aware of,) but he does own a big chunk of land, so it was speculated he was planning to develop ranches for the “copter class.”

Given a hedge-fund billionaire, Louis Bacon, purchased Taos Ski Valley not long before, started his own airline, and expressly began cultivating a super-rich clientele, such conjecture about our misfit heliport seemed just.

But nothing like that has come to pass, and I’ve never even seen the damn place used. It just sits there, jutting out of a cow pasture, and has more No Parking signs than parked cars, much less helicopters.

Until today, that is.

Ten minutes ago, I was perusing today’s book, preparing to write this column for you.

As I sat on the couch, (having only recently had the confidence to leave my bedroom as a workspace,) I heard a shocking roar that split the silence.

My head started throbbing, as a hellacious noise tore though the valley, and I quickly ran outside to see what the fuck was happening.

I looked to the East, and saw nothing, so I ran to the other side of the house, looked West, and there was a massive, military helicopter up in the sky.

It made no sense, as was it landing, or what was it even doing here?

So I threw on some shoes, grabbed my camera, (and a leash for the dog,) and tried to suss out what was up.

I watched the helicopter ascend, right after landing, and then circle the valley again, before coming in to land.

Again.

It lifted off one more time, did yet another circle, but this time, I had the camera ready, and a fast shutter speed chosen, so I could at least get some photos of the random, unsettling phenomenon.

I might mention our valley ends in a box canyon, which amplifies sounds like mad, so this particular military helicopter made me think of what it must have been like in distant, Afghan valleys, when those war ships showed up over the nearest peak, ready to fuck shit up.

Viscerally, I was afraid, though logically, I knew we weren’t under attack.

The copter did the same maneuver, landing and immediately rising, and then headed off to the South, (perhaps towards Kirtland Air Base in Albuquerque,) leaving the place as abruptly as it arrived.

Just now, my heart rate has dropped back to normal, and I’ve convinced myself it was just a training exercise.

That’s all.

But if my rapacious neighbor had never built that heliport, in the middle of a cow pasture, when there was no actual demand for such a thing, I would be a bit calmer than I am.

The architecture had a purpose in mind, and eventually, people always find a way to use things, once they exist.

Last week’s piece ran nearly 3000 words; likely the longest I’ve written in my 10 years as a columnist.

There was much to discuss, and I leaned in.

Today, as a counter-point, we’ll keep it brief, and relatively obvious.

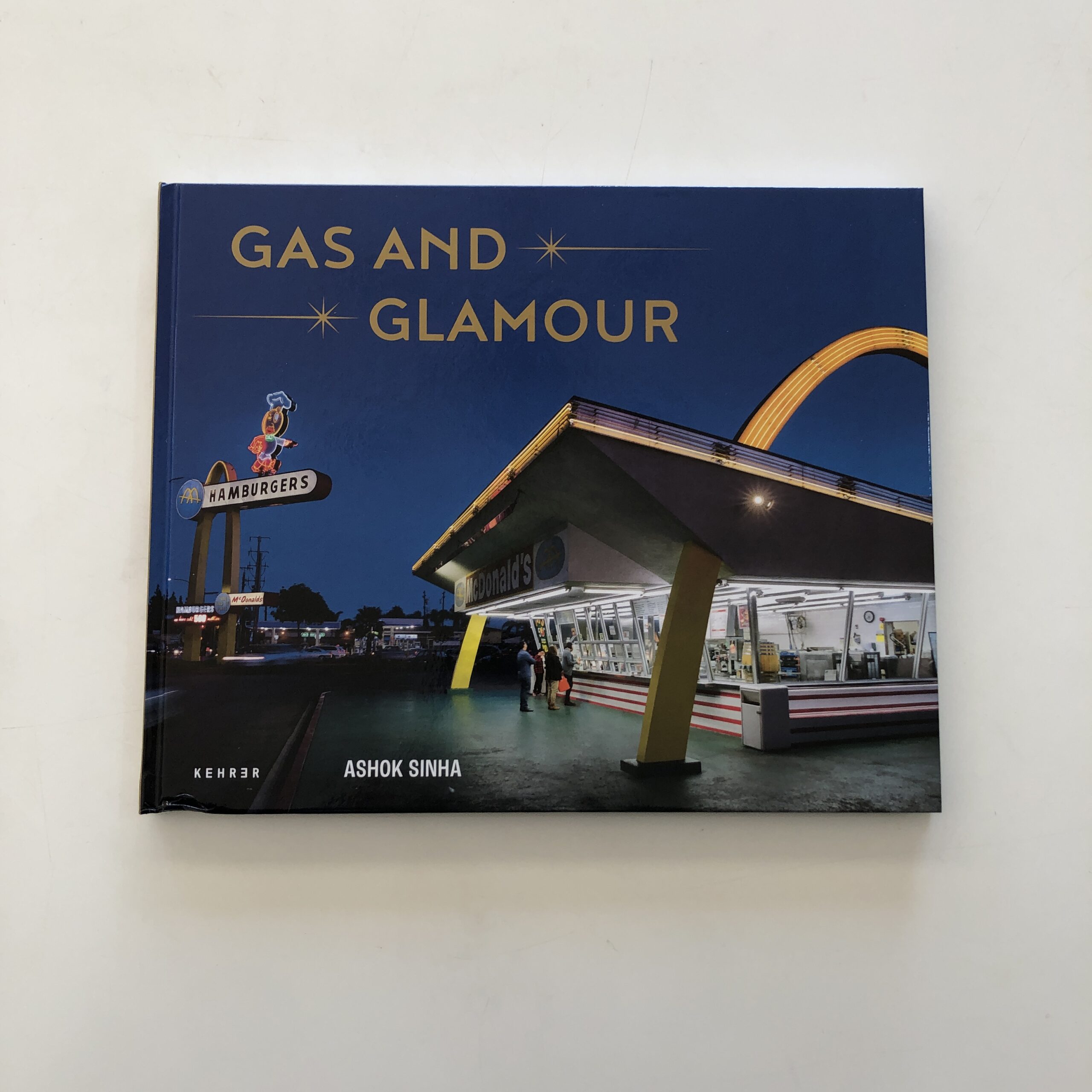

I’ll introduce today’s book, by Ashok Sinha, which showed up in the mail nearly a year ago. (I swear, we’re almost done with 2020 submissions. Maybe 1 more to go.)

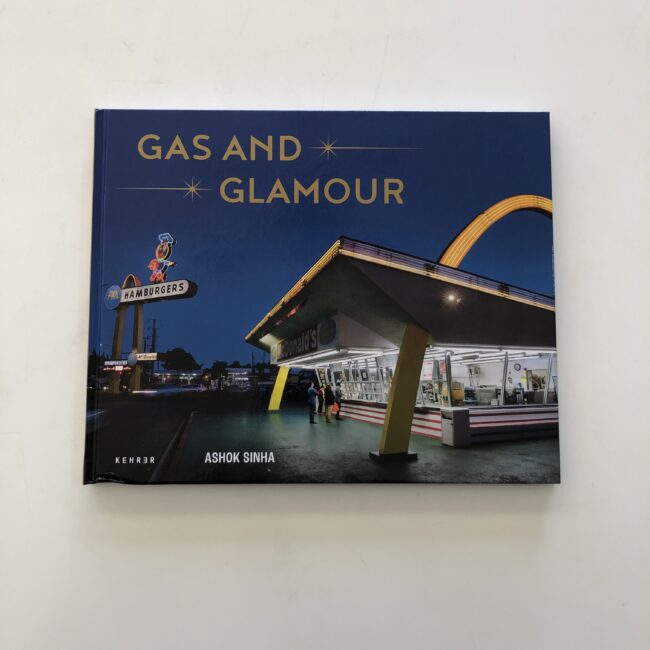

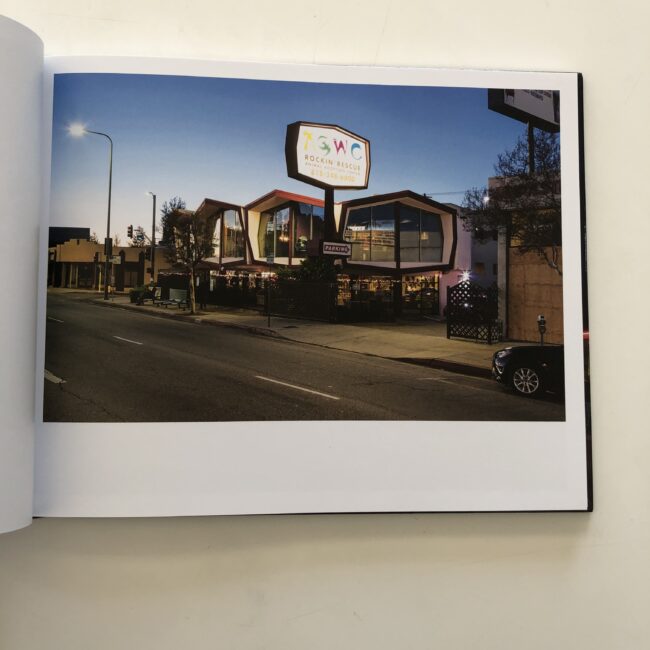

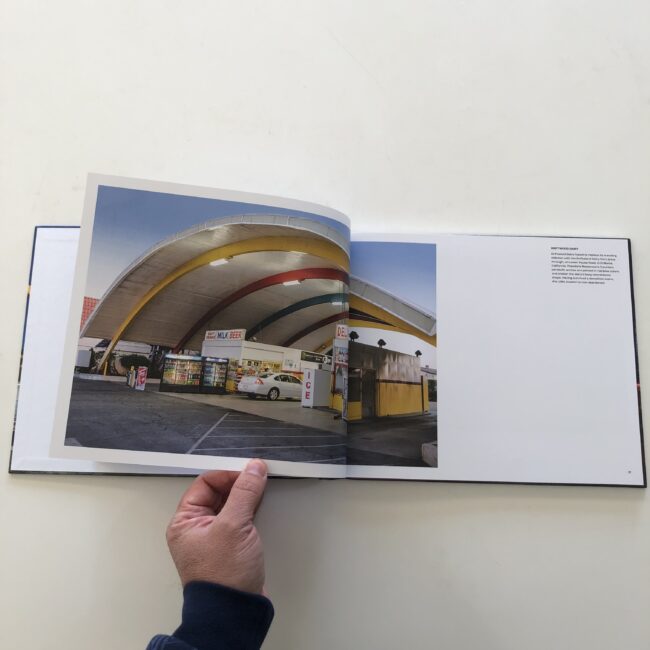

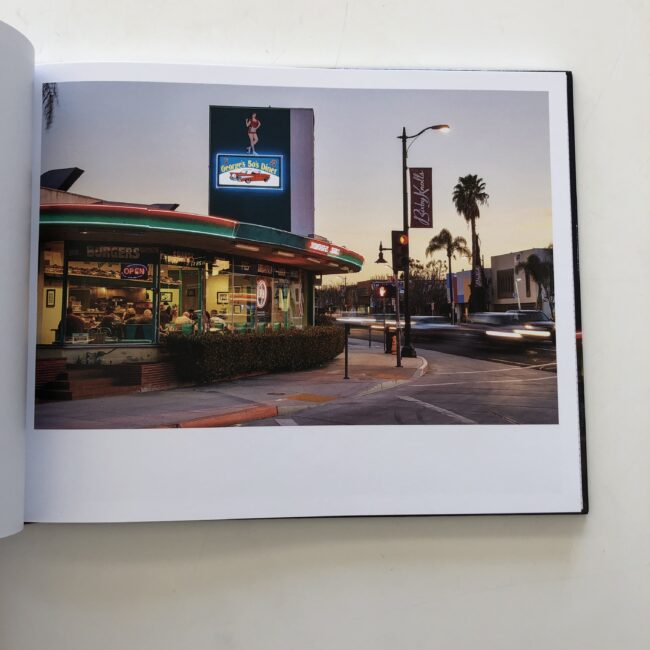

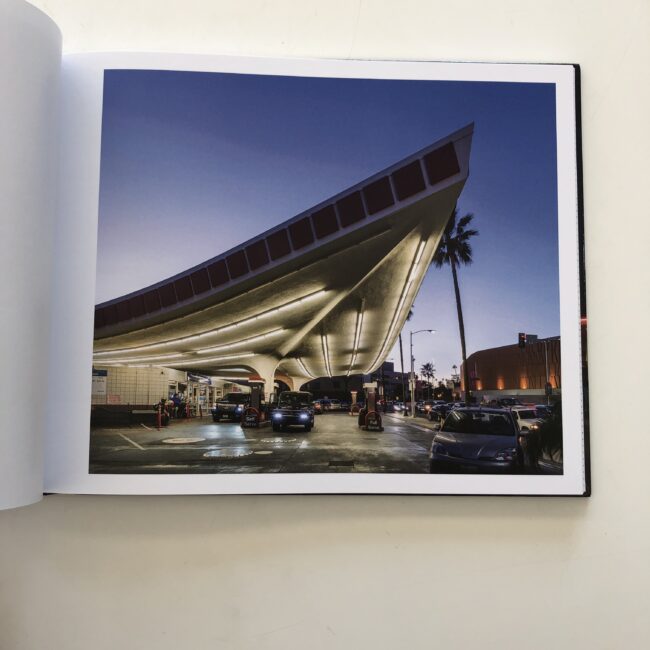

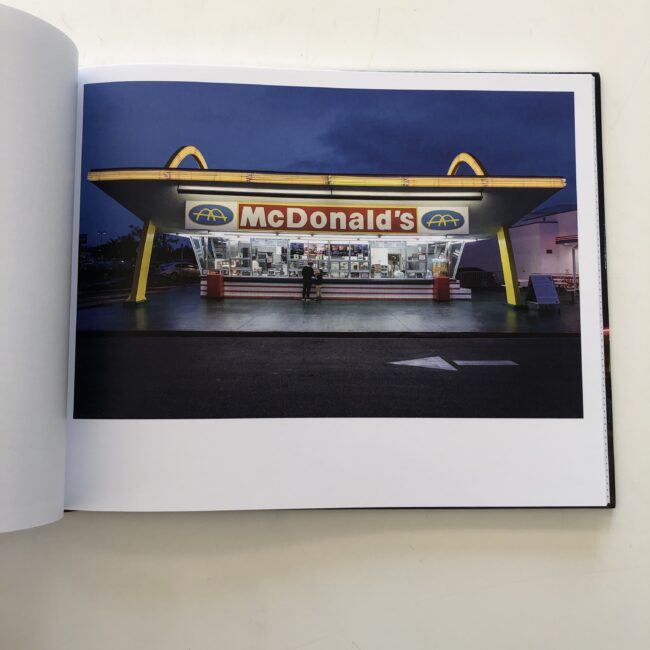

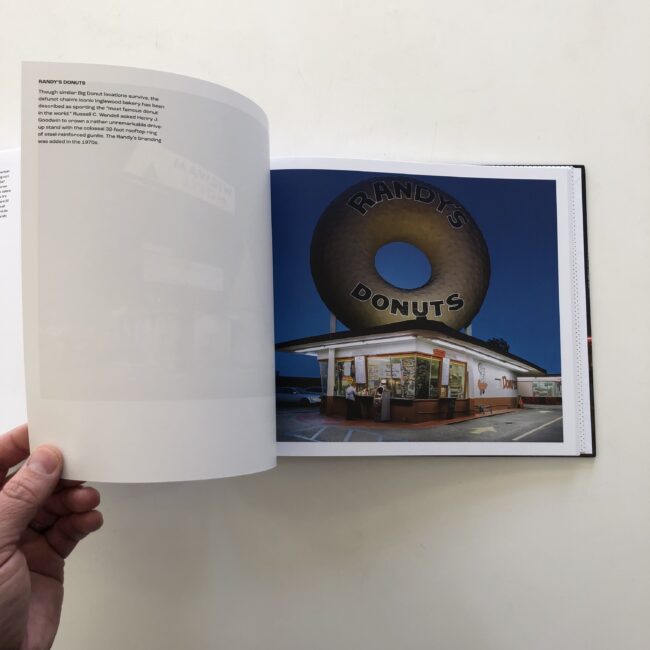

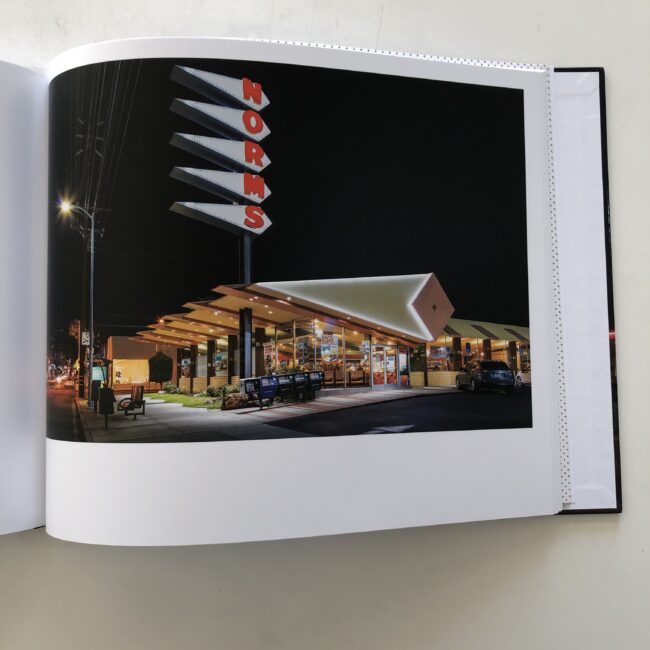

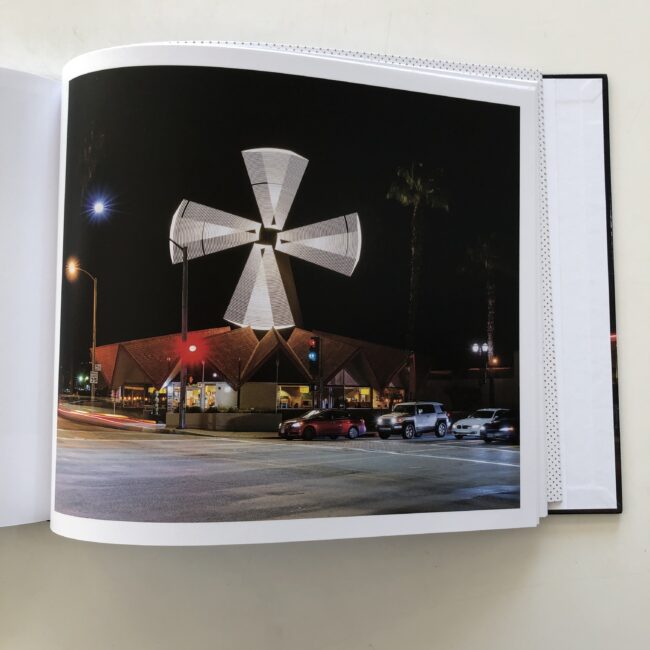

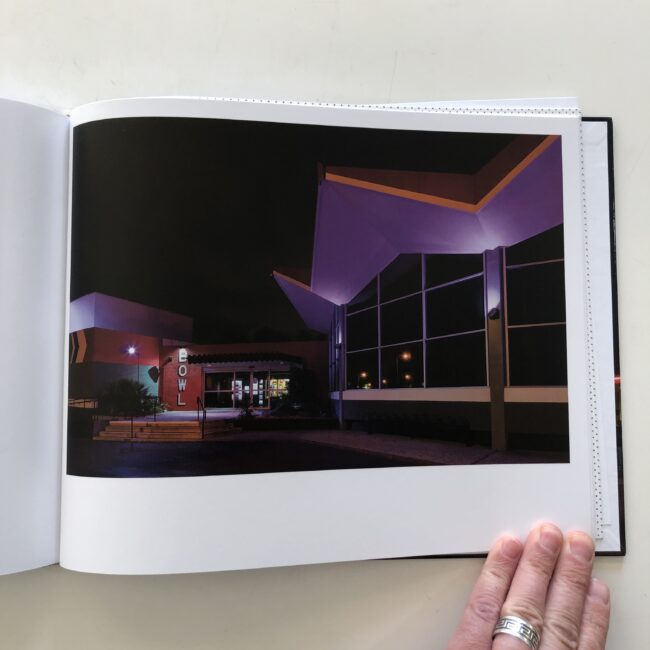

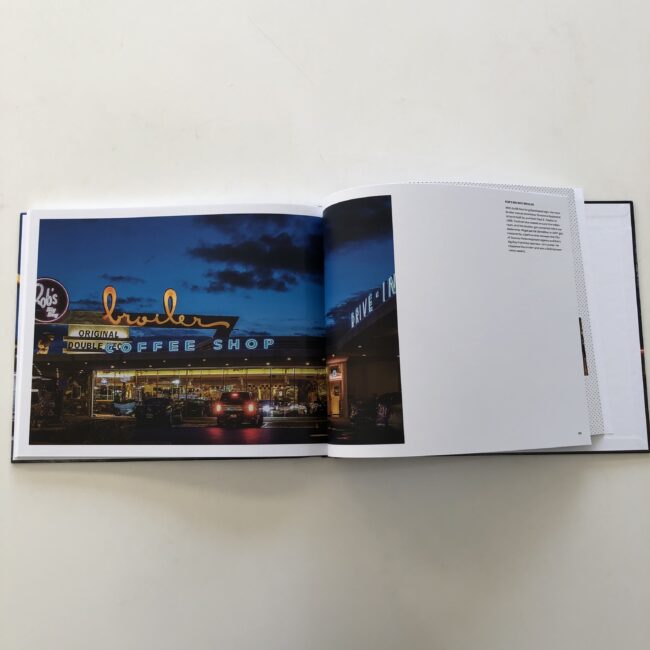

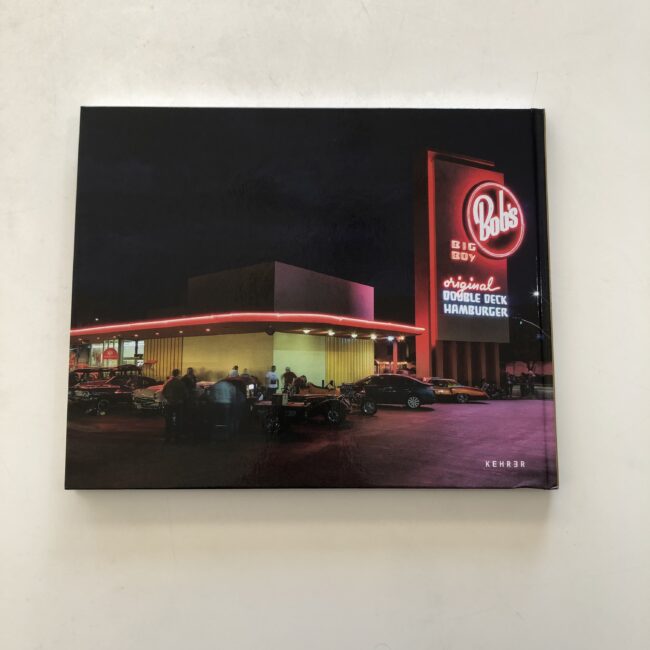

“Gas And Glamour” was published by Kehrer Verlag in Germany, and is somewhat straightforward, as is today’s review.

I met Ashok at an NYT event a while back, and we stayed in touch, so when he reached out offering a book about LA architecture, I said sure.

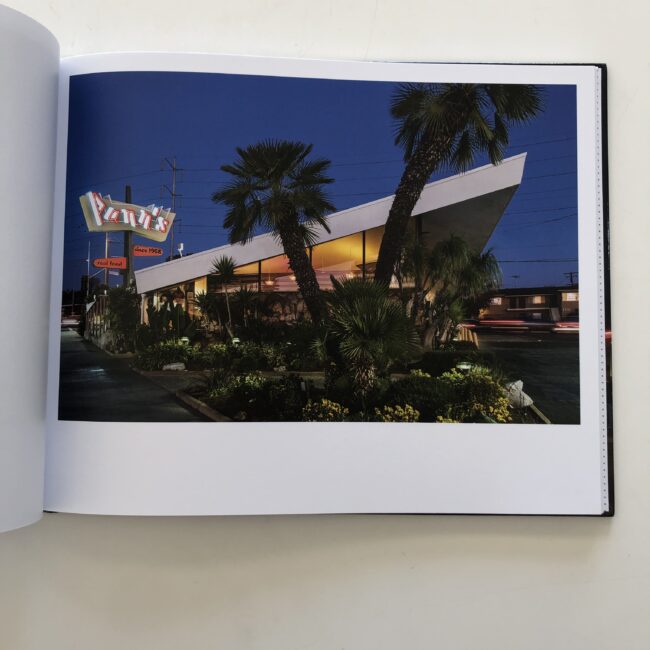

And given the magic of that brief sequence, in “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” where Tarantino wrote his love letter to LA neon, and old movie theaters, it seemed like this book would mine similar turf.

The quick gist is, I found this book flawed, and had questions about its construction throughout, but there were also strong elements to the production, so it felt like one of those “teachable moment” column opportunities.

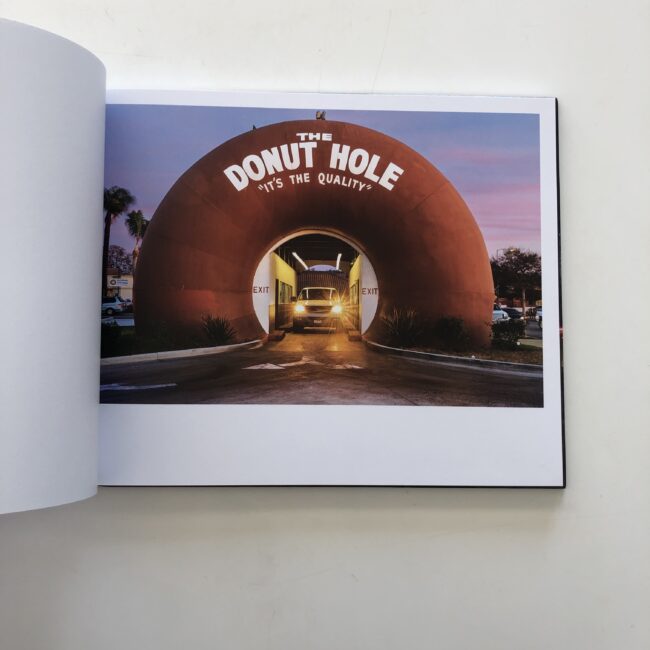

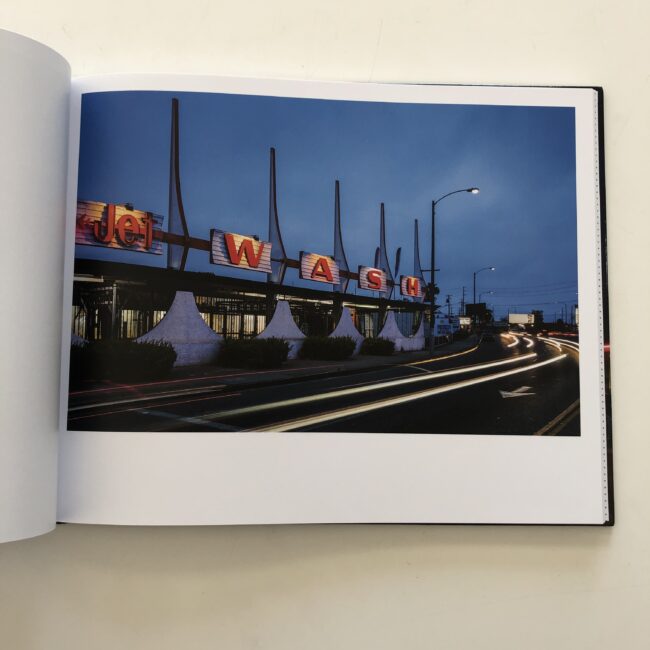

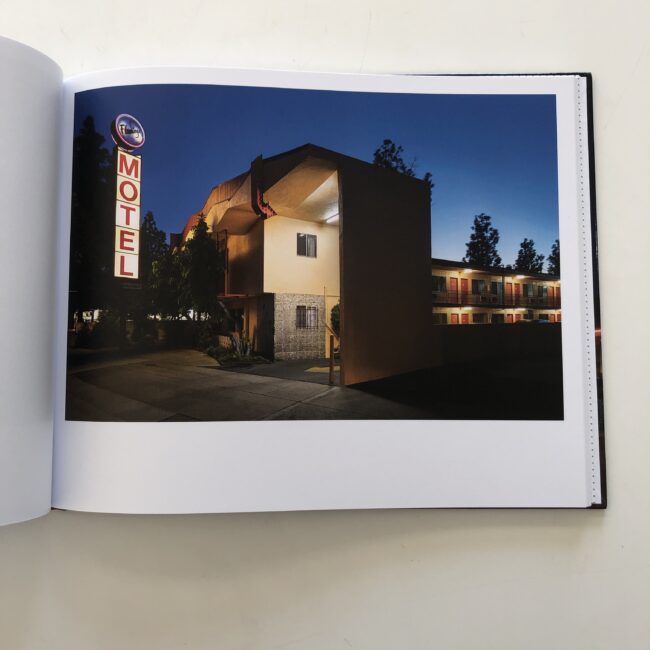

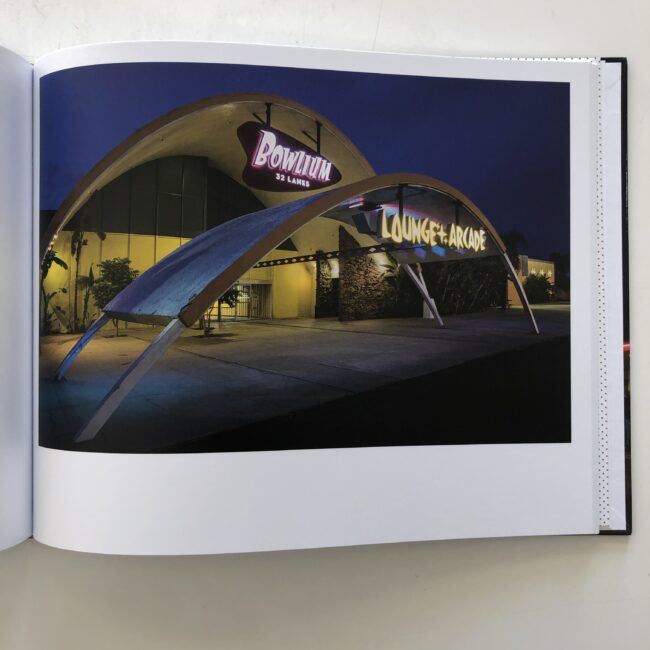

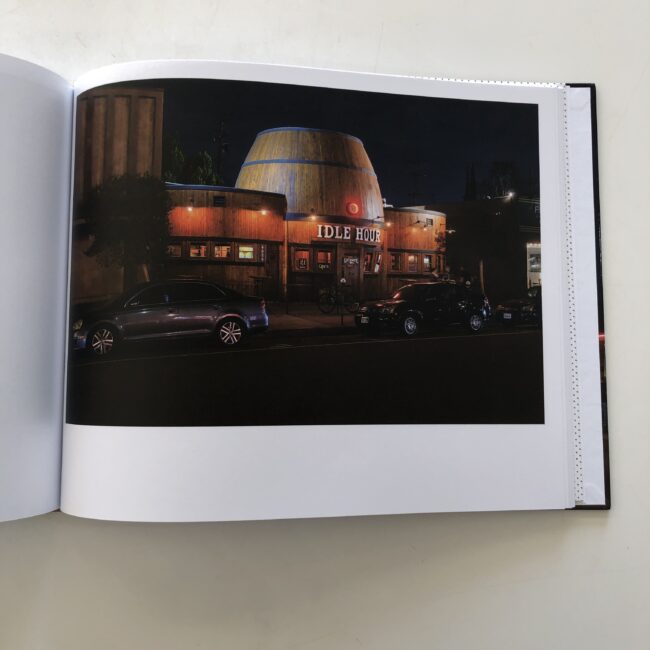

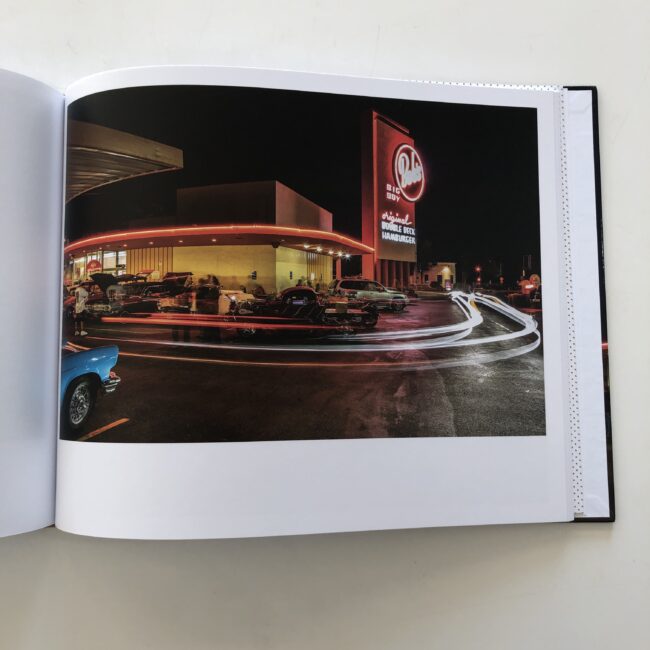

The project focuses on LA, mid-20th-century architecture, specifically buildings constructed for the burgeoning car culture that has since defined the city.

And the buildings are cool, to be sure, all shot in the gloaming, or at night.

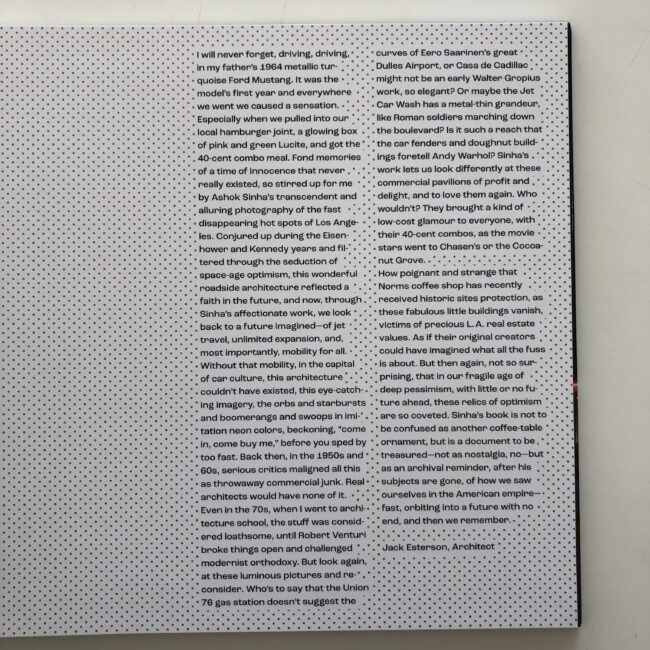

The two intro essays, which set the scene, are printed on paper backed with small polka dots, so the eye begins to swim in space while focusing on the words, which reminded me of those 80’s prints with the hidden image embedded within.

(“Just relax your eyes, man, and you’ll get it.”)

The photos are good, and a few are excellent, but throughout, I found myself craving more formality. As in, I wanted them to look like tripod, 4×5 images, in which the photographer waited as long as possible to get the perfect, insanely-well-composed shot.

I did not get that sense, as these feel more Canon 5D Mark II, and while I’m sure a tripod was involved at times, I didn’t feel it in my gut.

Additionally, the modern cars included in the frames felt like afterthoughts, as they did not add much formally, or to the color-palette, and I kept thinking, “Why didn’t you just wait another 20 minutes until the lot was clear?”

Furthermore, the few images that lacked cars, or light trails, did communicate that more weighted, luxurious viewing experience, which confirmed what I thought and felt were in line.

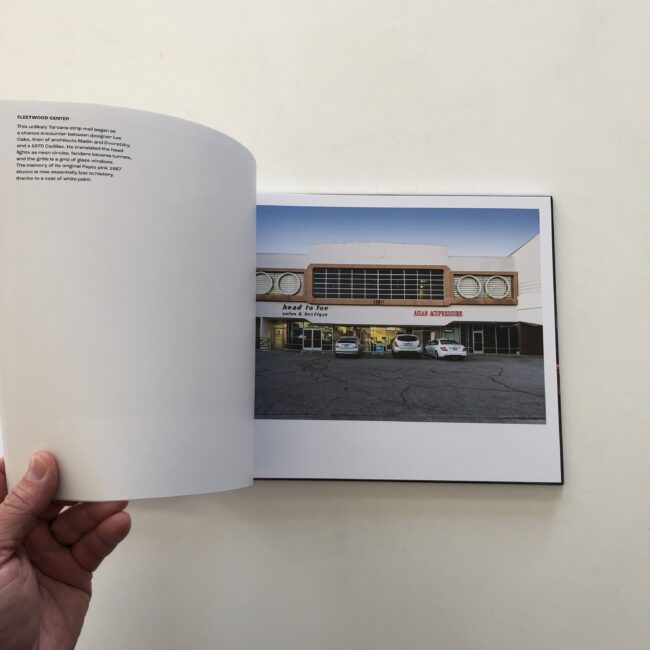

As to text, there were descriptive, historical captions included in the upper-left-hand-corner of each double-spread, but they were more informative than interesting, (to me,) so I began to skip the reading.

These, I thought, would be perfect for an index at the end, so I could choose to inform myself afterwards, rather than breaking up the flow of images.

“I wish,” I said to myself, “there were more images instead.”

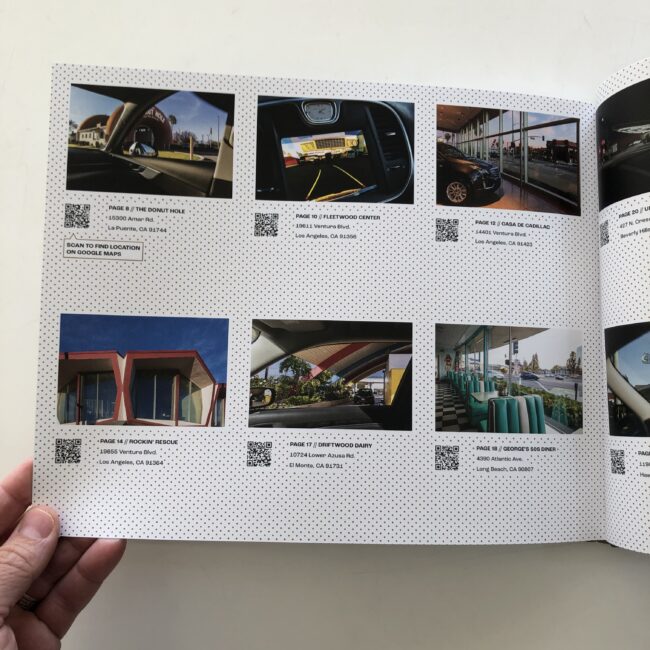

So I was quite surprised, at the end, to see an extensive index, featuring additional photos, including ones that showed the car in which Ashok travelled, as well as QR codes to give me the exact location of each building. (Which I would never use, though I’m aware others like the technology.)

“If only,” I uttered in my head, “he’d given us more dynamic images in the body of the book, and saved the textual info for the index, I’d have liked this book a lot more.”

Lately, I find myself telling book clients, and students with whom I meet, that every single part of a book needs to be considered.

All of it.

My design partner Caleb feels the same way, and when I recently interviewed Katherine Longly, she shared the same sentiment.

Think hard about every segment, and stress test those choices.

I don’t doubt that in “Gas And Glamour,” Ashok and his extensive team did think about the details. I guess I just don’t agree with the decisions they made, but it is literally their prerogative to make the book they want to make.

(And it’s cool, just not what I would have done.)

As a critic, though, it is my job to tell you what I think, and how you might avoid such (subtle) pitfalls when you make your own book.

See you next week!

To learn more about “Gas and Glamour” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are particularly interested in books by artists of color, and female photographers, so we may maintain a balanced program. And please be advised, we currently have a backlog of books for review.