I have a confession to make.

I haven’t made photographs, as art, in more than two years.

(Well, until the other day, but that was as a favor to my wife, so it doesn’t count.)

I haven’t made art with a camera in more than two years, and those pictures were crap. The tail end of my Party City series, and none of the 2018 images made the final cut.

Which means, as an art photographer, I haven’t engaged my craft for the longest phase of my adult life.

I’ve made editorial images for you, here in the column, but as a conceptual, studio based artist, it’s not the same thing.

How do I reconcile this?

Well, the way I learned about art, (and the way I teach it,) is that all avenues of creative expression are equally valid. It was assumed that most, if not all artists, would have multiple outlets in their creative practice.

So the idea that one was inherently better than another, or more noble, was never ingrained in my mind.

That I made photographs for my first twenty years as an artist does not have to be relevant to what I’m doing now, or next.

In #2019, I made installations in a museum exhibition, and worked on a set of pencil drawings, based upon portrait jpegs I took from the internet.

That was way out of my comfort zone. And I made a book.

Now, in #2020, I’m leaning into this column, because it’s a stable foundation in an unstable world.

Yet the camera has not called to me.

But like I said, photography isn’t the only way to express ideas, it’s only one of many. (I recently surprised someone on FB by proclaiming her banana bread counted as art.)

I’ve been teaching a long time, so much so that there were certain crutches I leaned on, year in year out, when I taught at UNM-Taos for 11 years.

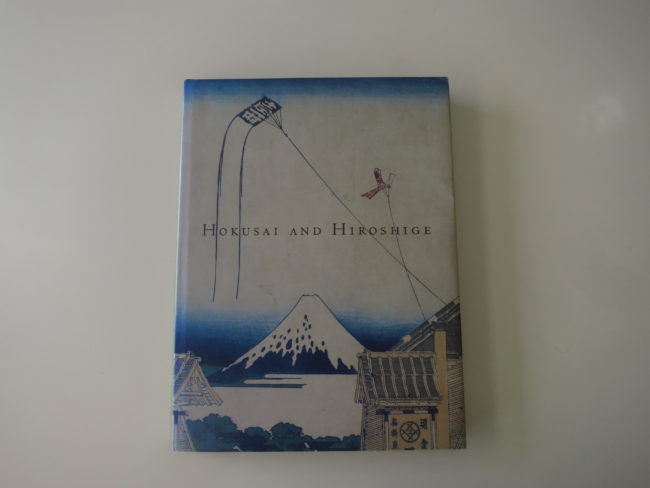

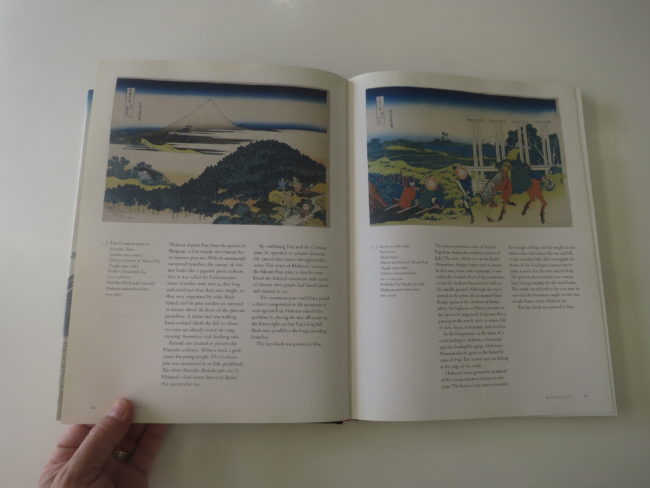

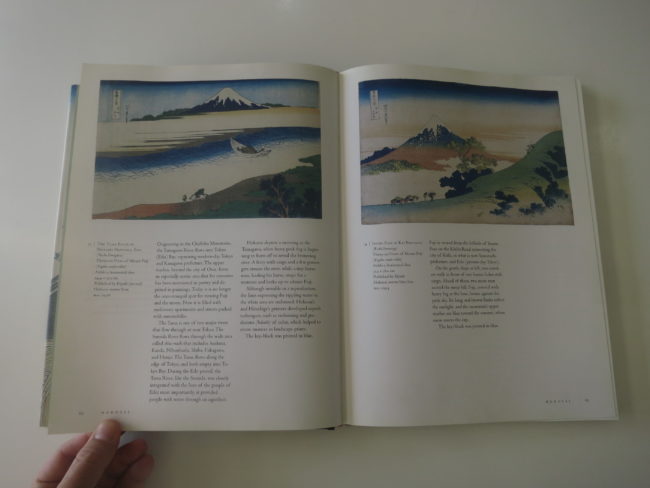

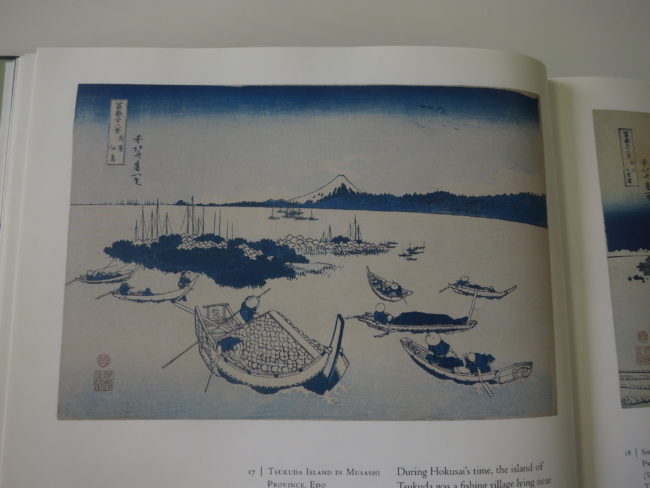

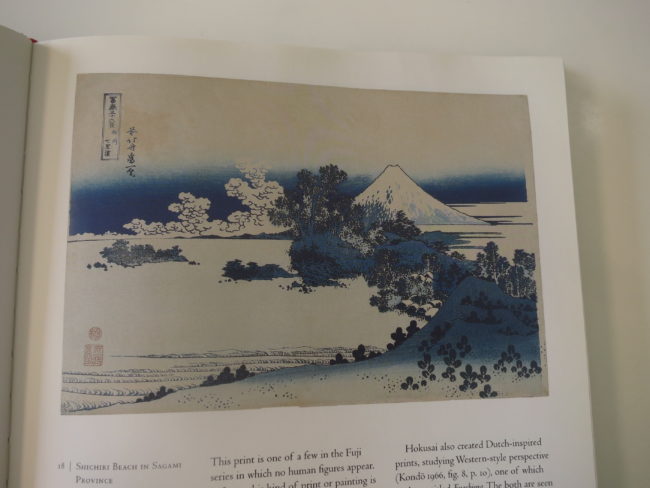

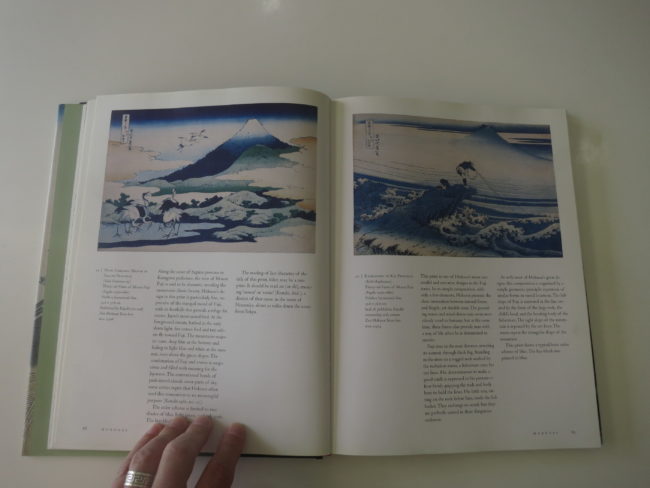

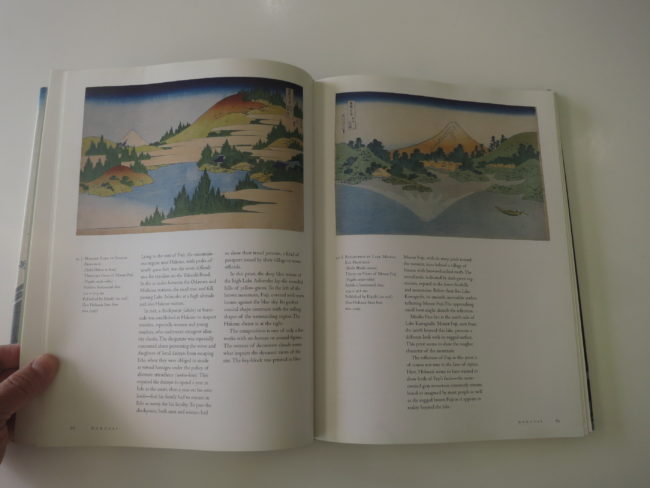

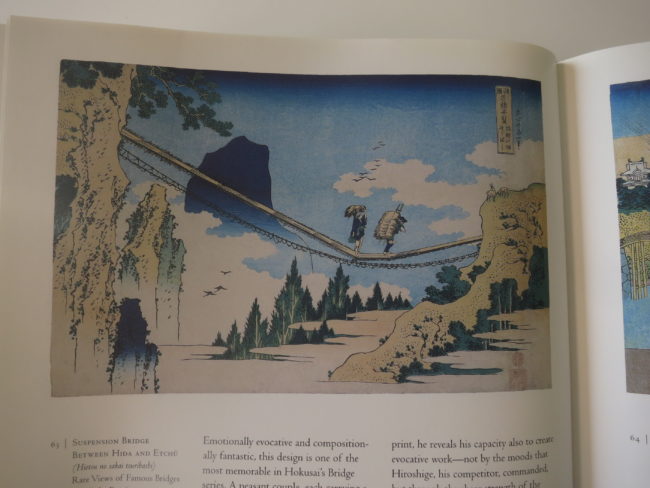

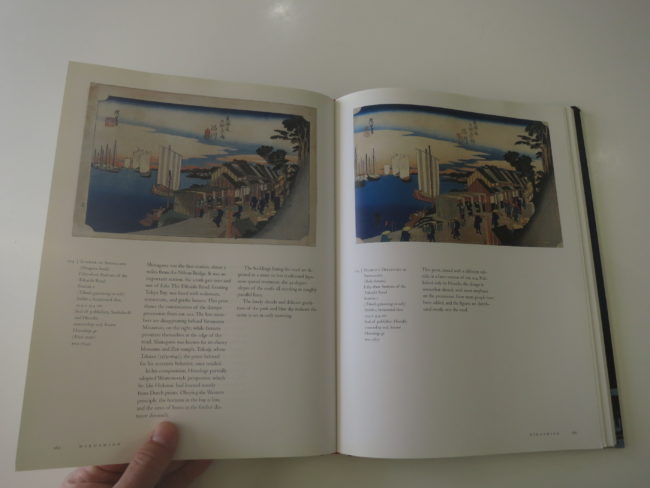

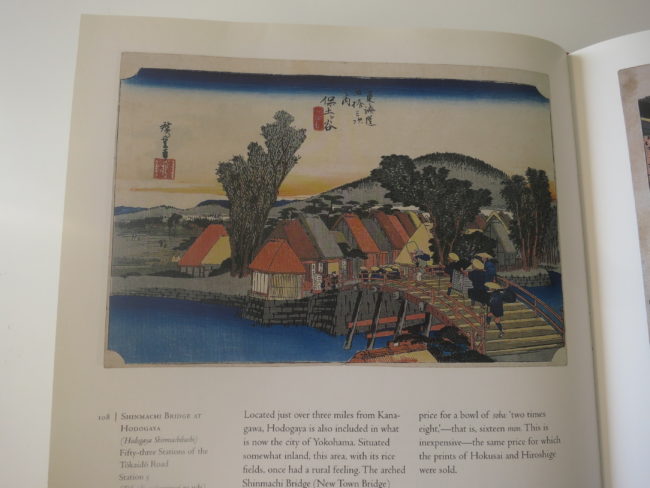

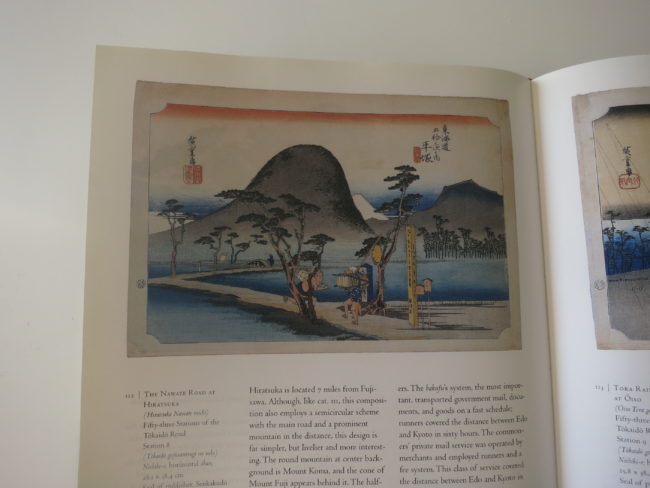

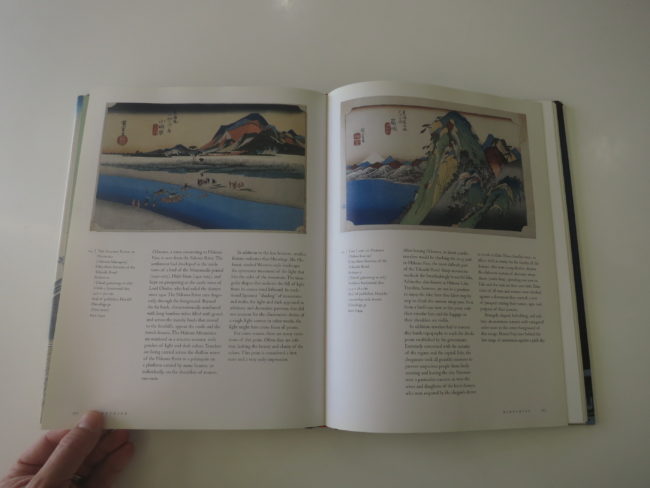

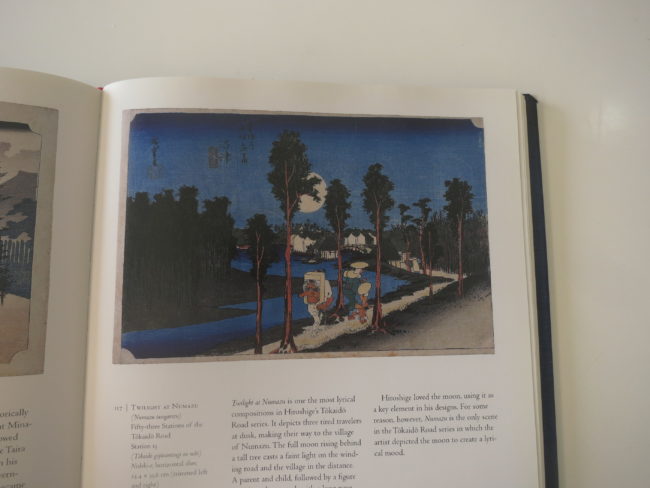

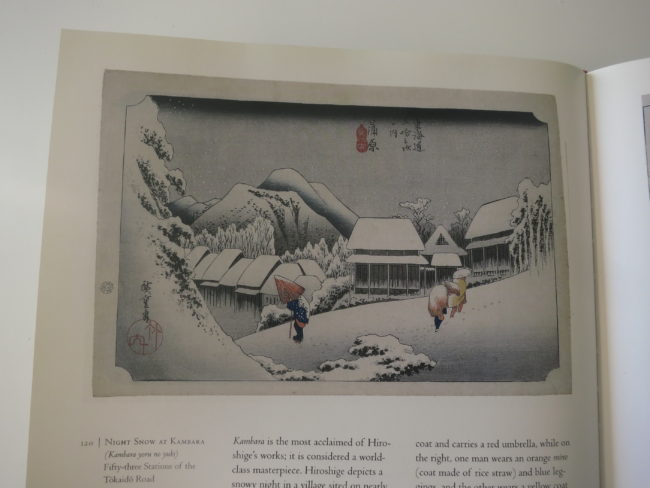

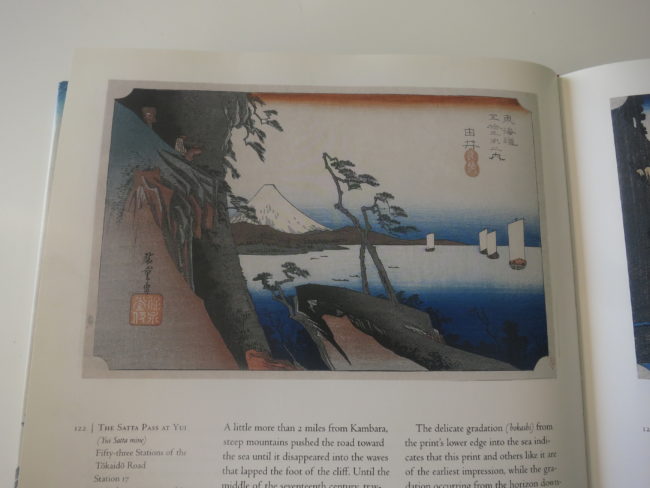

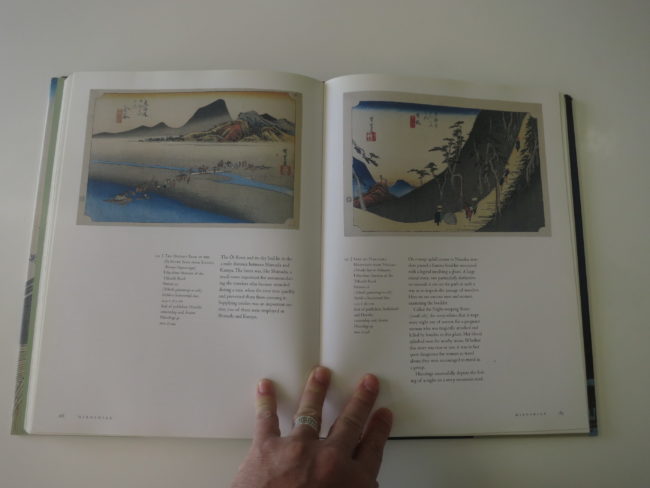

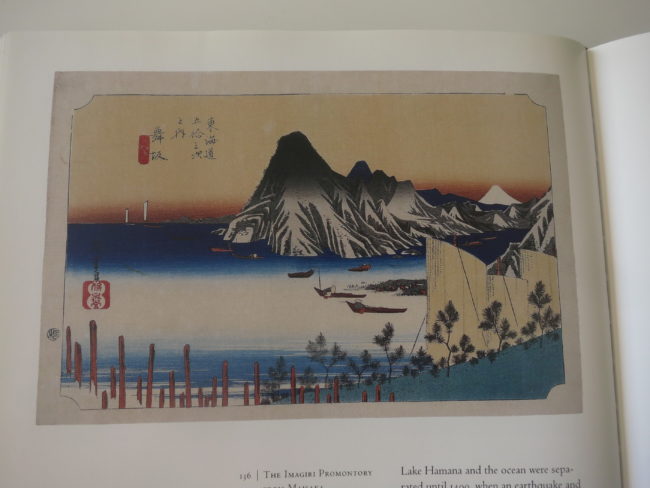

For teaching composition, for explaining the flow of visual information in a rectangle, I always used the same book: Hokusai and Hiroshige.

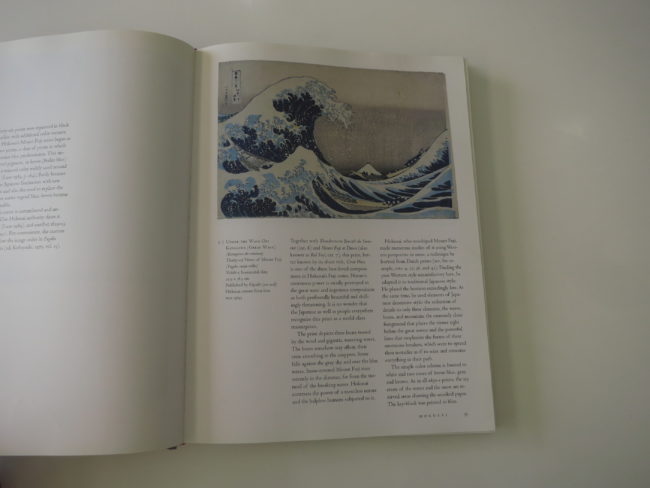

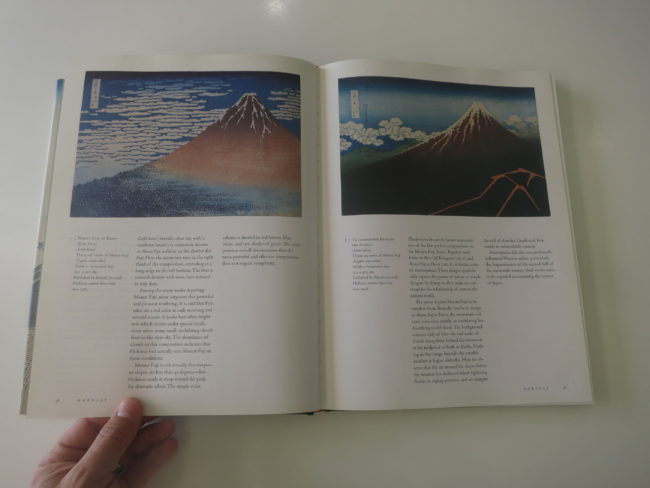

That’s right: I taught the crucial element of photography by deconstructing Japanese 19th Century woodblock prints.

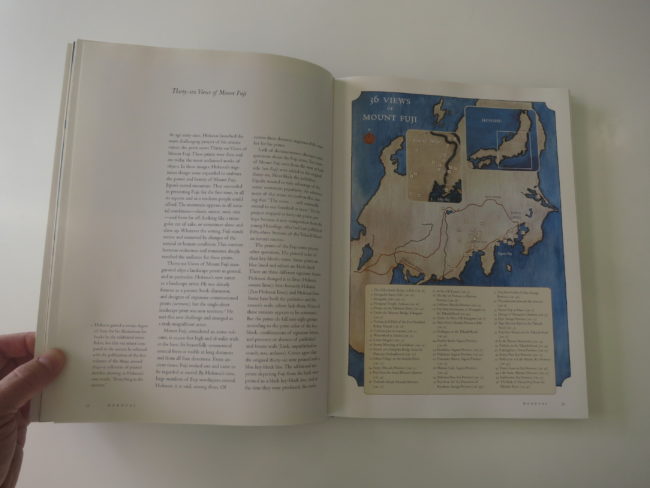

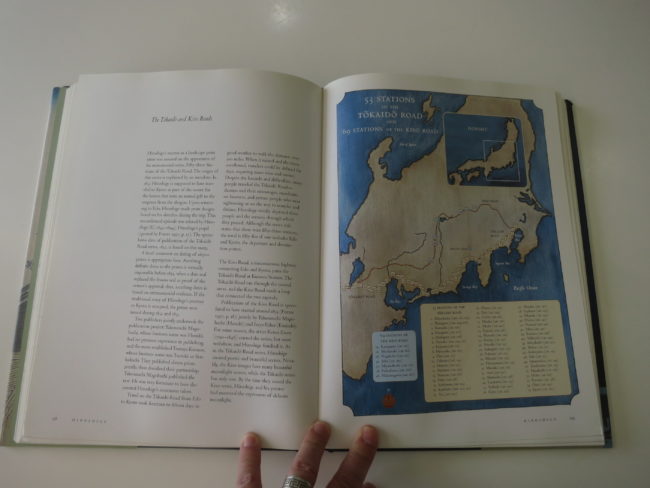

Year in year out, this book delivered the goods, as it features Hokusai’s famed “Thirty Six Views of Mt Fuji,” and Hiroshige’s “Fifty Six Stations on the Tokaido Road.”

If we dated it, I suppose the camera was invented in a couple of spots in Europe, with some overlap to this time period, but on the ground, printmaking was the way visual information was recorded in 19th C Japan.

And its mass production allowed the images to be collected by regular people, much like the 17th C Dutch middle class spawned so many great paintings.

I wanted to share the book with you today, because the serene colors, all sorts of blue, and then the snow scenes, white on white, are a visual gift from the past.

Why do I love them so, beyond the color, and the constant change of perspective?

Beyond the curvilinear water, the slope of Mt Fuji, and the ochre contrasts to all that blue?

It’s because this book represents a place in time so deeply, with the clothing and the postures and the boats and the hats.

This is what we have of then.

As in so many other cases, the art becomes the history.

Which brings me back to #2020.

To now.

I may not be making art photographs, (other than the other day as a favor,) and maybe you’re not either.

Maybe you’re drawing, or painting, or bread baking or dancing or gardening or yodeling or playing French horn or practicing your French. (Bonjour, je n’aime pas le yodeling.)

Or maybe you are making photographs?

Maybe you’re pushing yourself?

Maybe you’re making your best work, or are about to? Maybe all the frustration you feel, the anger, the anxiety, is going to spring up as something dynamic and meaningful?

I’m asking, because last night, I saw some new work from my friend, and former student, Andy Richter, during an online critique I set up for the alumni and expected attendees of our Antidote Photo Retreat. (Andy was the 2019 Antidote Fellow, as he came out to run a morning Kundalini yoga program for us, along the acequia.)

During our group crit last summer, I pushed him to go beneath the surface. He was showing some aura portraits, with strong colors, were perhaps more style than substance.

As an artist, I thought he had more digging to do, and I told him so.

So that’s the context for understanding why I was so happy for Andy, seeing his new series, currently titled “Walking with Julien,” which received Minnesota public funding for an exhibition in Spring 2021.

All the images were taken on walks with his young son, around his diverse Northeast Minneapolis neighborhood, (he’s originally from MN,) and everyone on the Zoom call, including an important museum curator, was blown away by the work.

The portraits, in particular.

Andy confirmed that certain aspects of fatherhood were tough, as it constrained the freedom to which he was accustomed. (This is a guy who photographs hermits deep in caves in India.)

And now, even worse, like the rest of us, he was literally stuck at home. With his neighborhood as his unexpected muse.

He admitted, as many artists have before him, that the combination of inner necessity and logistical constraints has perhaps forced him to see more deeply.

Are these meditation walks?

Does it matter what we call them?

So I wanted to share the story, and some of the pictures, with you here today. And Andy was gracious enough to agree.

Some days, maybe some times every day, things might seem grim.

Certainly, I never thought I’d long for the insanity of #2019, but here we are.

Please remember, art is best at times like these. It helps your psyche, day to day, and it records the moment for the future.

Stay safe, and see you next week.