TIME

Design Director/Creative Director: D.W. Pine

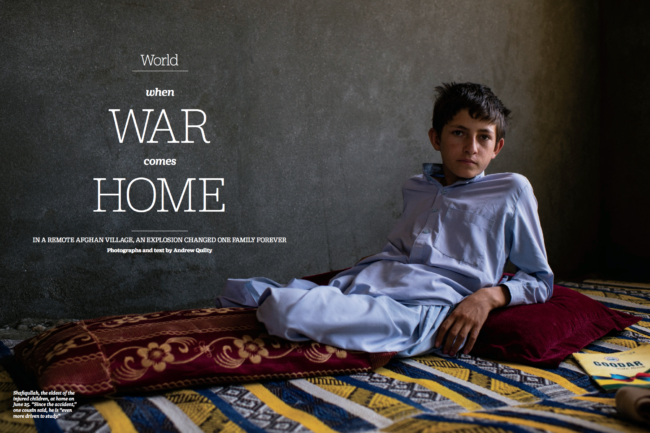

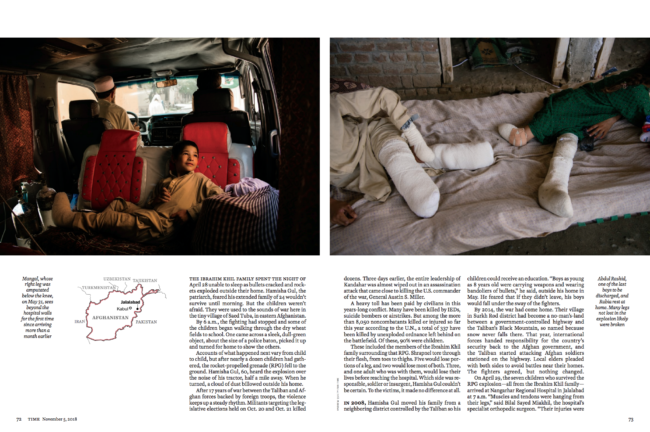

Photographer: Andrew Quilty

Heidi: How has politics shaped your work there?

Andrew: American foreign policy since 9/11 shaped my opinion and much of my mission here. I’ve been focusing on Afghans rather than on Americans in Afghanistan. Granted it’s little bit easier for me to concentrate on Afghans over Americans because I am here at a time when the American involvement has been significantly reduced, especially in comparison to 2008 to ‘12. Having said that, America’s involvement in Afghanistan since 2001—and it’s failures—affect affairs here on a daily basis. It’s hard to separate that affect from any subject a journalist might choose to look at here, and I don’t think it should be

What was your sense of the country before you arrived?

When I came here, all I knew of the country was what I had seen through the media

I have this photo in my head: 10 camouflage-wearing soldiers walking through a dusty village or across a dusty plain. Before 2001, I wouldn’t have even had that. I wouldn’t have even been able to place Afghanistan on a map, let alone tell you who was there, who’d come and gone or who was in charge on September 11.

What drives you?

More and more, I feel an obligation to redirect the minds of readers and viewers who, for the most part, like their governments, are only interested in Afghanistan insofar as it effects them or their national self interest. It’s playing out now with America’s number one priority during peace talks with the Taliban being a guarantee that Afghanistan won’t be used as a base for terror groups with international aspirations, with the future for Afghans seemingly a distant second. There’s some anger toward the Americans and their allies for the hubris that allowed them to think they could mould yet another country that was only moderately willing into a shape more suitable to them. And there’s probably some guilt that I’m from one of those countries that followed the U.S. in, blindly, driven by emotion and revenge.

How do you think your images would have been different had you

been in the country earlier?

I don’t want to criticise those who came before me because, in the early years of the war there was an appetite for what the international soldiers were doing. Of course readers from Australia want to know what their soldiers are doing; why they’re fighting and dying and coming home mentally ruined. I have no doubt that if I was here, then, I’d have been covering the international military mission almost exclusively, too. But what we rarely heard about were the Afghans affected by the war. The innocent ones being killed in horrific ways. Or why, after the Taliban had been ousted, were people turning against their “liberators.” Afghanistan was still depicted in simplistic way: government good, Taliban bad, when the reality was far more complex. That simplification not only damaged the international public’s understanding of Afghanistan and the deteriorating situation here in recent years, it also ensured the failure of the international military mission and built a culture of corruption into the government and its institutions.

Is this a reaction to how the media has imbalanced everything?

It wasn’t about Afghanistan. No one really cared about the outcome for Afghanistan. It was-and still is-all about Afghanistan in relation to how it will affect America. So I just find that a little unfair.

How are you trying to humanize this in your own mind?

I think about the people who had no say in this. First they were given hope, then despair and the whole roller coaster that’s ensued. What about them? International interest has tended to focus more on those who made the choice to come here. I hate the cliche of the journalist’s roll being to speak for the downtrodden, but when the balance is so far out of wack, as I feel it was through the majority of the war, and when those who have, and continue to impose well-meaning but dismal policy and strategy are all but impervious to reproach, it’s hard not to back the underdog.

What speaks to you about this experience?

and what is misunderstood by those that consume your work?

Well, look, I think a lot of people assume that I’m here out of some sense of vocation– and yeah I think that’s part of it but I also think there’s a lot of other things to consider. I actually quite like my life here outside of my work. Although work is pretty all-consuming, I happen to love the work that I’m able to do here. But my point is, a lot of people assume I’m making huge sacrifices and taking massive risks being here, and that I’m doing it all for the sake of the Afghan people. In general, I don’t even think photographers and journalists are particularly empathetic people. That’s a myth that viewers can easily fall for by looking at the kind of subjects many of us focus on but I don’t think it’s entirely accurate. Sure, I get affected by things here – I’ll have to wipe away tears while listening to people tell their stories and I won’t sleep a wink for a couple of days after being close to a bombing but I’m not sure a deeply empathetic person would last long—assuming they had the choice to leave—in this kind of environment. I suppose it’s a journalist’s job to be able to switch it on and off; to be able to channel it into words or pictures rather than letting it overwhelm ones soul.

What is your life like there?

I manage a nice old Afghan house that’s home to two dogs taken off the street before I arrived and an assortment of others, mostly journalists, who stay for varying lengths of time. I read the news over breakfast and coffee most days and, if I don’t have something specific to work on I’ll try to get out on my motorcycle to shoot some pictures. As a photographer, I don’t think I’ll ever get tired of this city. Aside from that, like any photographer or journalist, I’m planning trips into the provinces, pitching or filing stories, sending invoices, responding to emails and, twice or three times each week I’ll do something social, usually dinner or drinks at a friend’s place, taking a new housemate along on the back of the bike.

Are you married? Do you have children?

No. No, no. Neither. I’ve had a couple of semi-long-term relationships here in Kabul. But I’ve never dated an Afghan. The foreigner crowd here is a good group of people, by and large. They’re all in similar life circumstances – no kids, no mortgage, maybe or maybe not married. So it’s a bunch of people who are at a similar stage in their life and they’re usually pretty good at what they do. It’s like small-town life with people who have chosen to eschew small-town life.

Dinner table conversation is always really interesting, save for when it inevitably turns to matters of security in Kabul. But that’s a bonus. Obviously good dinner table conversation wouldn’t be enough to keep me here if I didn’t love my work, as I do in a way I never have before. Back in Sydney, I was probably really invested in 20% of the work I did. I cared about it. I cared about what I was photographing. The other 80% was what I had to do to pay the bills. Here, I mean, it’s beyond the inverse. I mean, there’s very little that I photograph here that I don’t find interesting, that I’m not personally curious about or that I don’t think is important. It’s very hard to find a subject here that isn’t in some way affected by the country’s history, and that history makes those subject’s stories compelling in a way that is rare, especially somewhere like Australia. As a photographer, it’s hard to turn away from that.

When I go on your Instagram and see what you are publishing if looks like an incredible opportunity, photographically to personally grow so I would understand why.

Yes.

You’re going to come out the other side of this immersion a completely changed person, Most people wouldn’t even think about trying…

Yeah, very much so. Most people assume that you can only come out the other end of a period working as a photographer in Afghanistan as a diminished person, damaged by what you’ve seen. If I left now, I’d leave a richer person than the one that arrived here five years ago.

You’ve said you arrived in Afghanistan and just knew that was it.

Many people struggle to craft a voice. What I enjoy about your work is — I feel like you’re happy. You’ve zeroed in on a very distinct voice and eye and you’re able to articulate your pictures. It’s fortunate that you’ve found this calling because most people search for this their whole lives.

Yeah. Yeah. I know. I know. And I didn’t even knew I was looking for it. I thought I was satisfied in the work I was doing back in Australia and from New York, and now I look back on it, and it’s like BC/AD – before and after I came to Afghanistan. Now, on my website, I don’t have a single picture that wasn’t taken in Afghanistan. It’s a very distinct line for me. It’s also helped me realise the potential of photography as a means to tell stories, or to inform, in a way I’d never understood.

I’m sure that there’s some haunting things that you’re seeing, too. How do you cope with that?

I try to look after myself and eat well and exercise and all those things. Speaking with friends. I mean, that’s the good thing about being here. Everyone is in the same boat, and strangely enough, some of my fondest memories here are of the nights following either a big bombing or an incident where someone we know has been killed or injured. Coming together with a small group of friends, just being together, helps. What was that line in the movie Speed? Something about relationships formed under intense circumstances. Those will certainly be some of my strongest memories.

It’s rich. It’s real life that’s so visceral.

Yeah. It’s real experience. Yeah. And also part of the reason which makes it hard for me to think about leaving, and most people seem to think I should.

Right. They’re probably afraid for you. People project and can’t even imagine themselves doing that, so it’s natural.

Yeah, of course.

Do you pitch stories written and shot by you?

Yes, I pitch stories myself and write them myself as well. But that’s relatively new. It came as a result of some of people I used to work and travel with leaving the country. All of a sudden I had to rethink where my assignments would come from, whereas previously, they tended to fall in my lap. Not only that, the stories attached to the assignments stopped coming, so, almost overnight I had to start thinking for myself. It’s a new way of working for me. Where I started my work as a photographer, at The Australian Financial Review in Sydney, I’d be handed my assignments on a piece of A4 paper each morning. It was very rare that I ever had to think for myself. It’s a bad habit that many photographers are bred into. The best photographers, I think, are thinking photographers, the ones who know their subjects intimately, rather than just turning up for a day after the writer has been and gone. So it’s actually been a blessing in disguise, and a challenge

Tell us about the making of this photo which was nominated for World Press Photo for 2019.

I was in a shop, below street level, about 200 metres from where a man driving an ambulance packed with explosives detonated when he was stopped at a police checkpoint.

I was asked a similar question when I was home in Sydney recently. I was sitting on on a beach on a hot summer day with some new friends. They asked me about the worst thing I’d seen in Afghanistan. Without much enthusiasm, I gave them the thirty second version of what followed the explosion. The reaction was predictable. The kind of shock expressed to fulfil the social obligation of revulsion, not through actual revulsion, because how could anyone who hasn’t seen something like that conceive of how horrific it is? But we should be horrified. It was at that moment that I decided, if I was ever asked about it again, that I’d tell the whole story or not at all.

1 Comment

[…] post The Daily Edit – Andrew Quilty: TIME appeared first on A Photo […]

Comments are closed for this article!