“I would argue that Manifest recapitulates the dehumanizing role of division in the conquest of the Frontier, by divorcing agency from lifeworld.”

–Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa, November 2017, in the official essay for Manifest

You might need to read that quote a couple of times to understand it.

I’m pretty bright, (so they tell me,) and I’m still not sure what it means. In effect, I’m tipping my hand about the book I’m reviewing today, but we’ll get to that later.

(As always.)

Rather, I’d like to focus on the use of language itself up above. One of the things that distinguishes this column from other spaces that investigate photography is that I endeavor to come across as a “regular” guy.

We talk about big ideas, sure, but I wrap them in jokes, or Pop Culture references. There was a time when I was a fan of flowery similes, but after the NYT got a hold of me, I began writing clause-packed sentences dense with information. (Like this one.)

Even so, it’s important to me that the language I use is accessible, as I want people to understand what the fuck I’m talking about.

In the tradition of the great inscrutable Frenchmen, (Derrida, Foucault,) some writers, and their attendant writing, rather aim to create barriers around their concepts. They utilize words like solipsistic, tautology, hermeneutics.

I’m sorry, but most Trump voters, the populi to his populism, would get angry reading a sentence like the one I lead with today. (And in fairness, the sentence that followed it DID include the word solipsistic.)

It makes people mad to feel like they don’t understand something.

That they’re dumb.

That you’re smarter than they are, and you know it.

I think that feeling, that sense of inferiority, of being looked down upon by rich people in the fancy house up on the hill, (Shout out to Luke Cage Season 2,) is at the core of what people mean when they say “elites.”

Elites are college educated urbanites. (Or in some cases, suburbanites.) They like arugula, and The Daily Show. Even better, they like the opera, and caviar.

Heartland America, when it rebels against “elite” culture, is reacting to a sensation. It feels bad to be looked down upon, but now, in 2018, these folks are having their moment.

(But before I get too empathetic, you have to watch this Daily Show clip about what Trump voters think of the Space Force.)

The history of the US is littered with pendulum swings: the liberal 60’s begat Nixon, the Reagan-era gave us Clinton, whose sleaziness made W. Bush seem wholesome. Then he ushered in Obama to clean up the Great Recession mess, and those who hated him have their savior in Trump.

But in classic Trumpian fashion, Il Duce managed to take the rhetoric to previously unseen heights at a recent rally.

He said, “We got more money, we got more brains, we got better houses and apartments, we got nicer boats, we’re smarter than they are and they say they’re the elite. You’re the elite, we’re the elite. Let’s call ourselves, from now on, the super elite.” (Courtesy of The Hill)

That’s where we are in 2018, people.

It’s all happening.

But still, I’ve been pushing myself lately to remember that Red America is still America. If we want to remain one country, at some point, we have to accept that the other “bloc” that has different opinions gets to win elections and enact policy too.

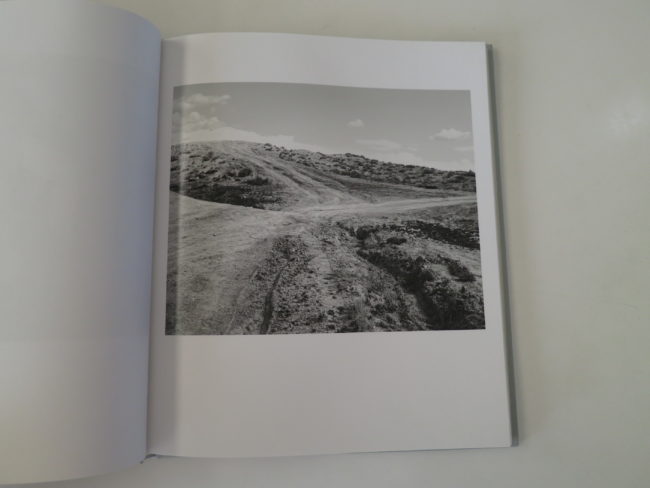

The American West has been solidly Red for generations, though places like New Mexico, Colorado and even Nevada have recently cleaved off from the herd.

Most of the West, with its wide-open landscapes, and unimaginable space and scale, still feels like it always has, at least in the 30 years that I’ve been around the joint.

Beyond the people who were born here, some places draw new residents with their “outdoor lifestyle,” “hip coffee shops” and (Insert random developer’s phrase here.)

Places like Denver.

And there are glamorous-view-spots throughout the West too, like Telluride, Sedona, or here in Taos.

Still, these spots are specks of dust compared to the enormity of the West. Most of it is dry and dusty. People are poor, and in some places live in conditions that one can reasonably call “Third World.”

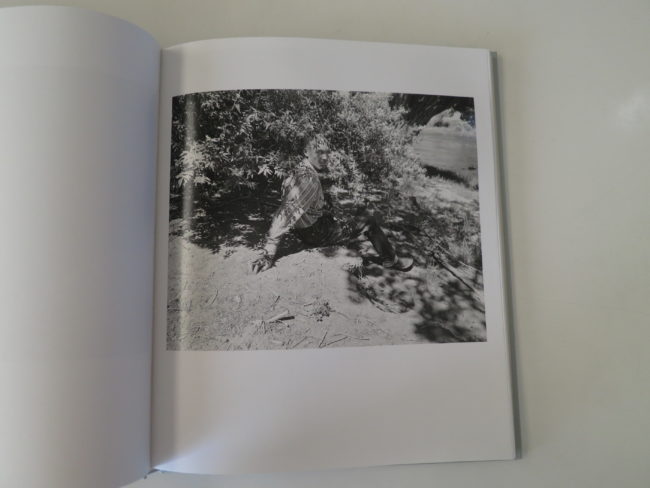

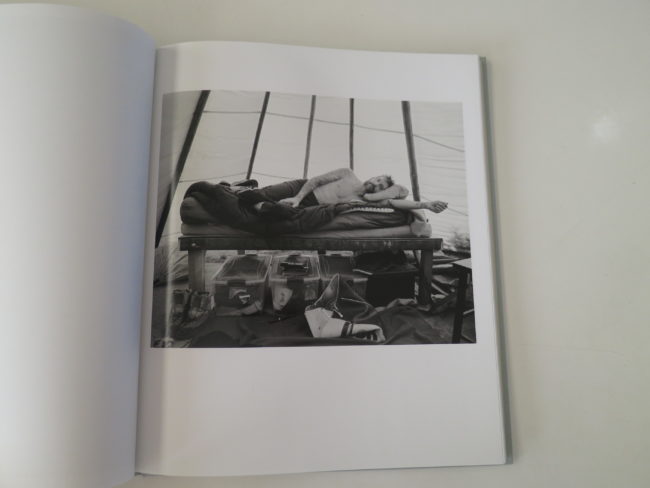

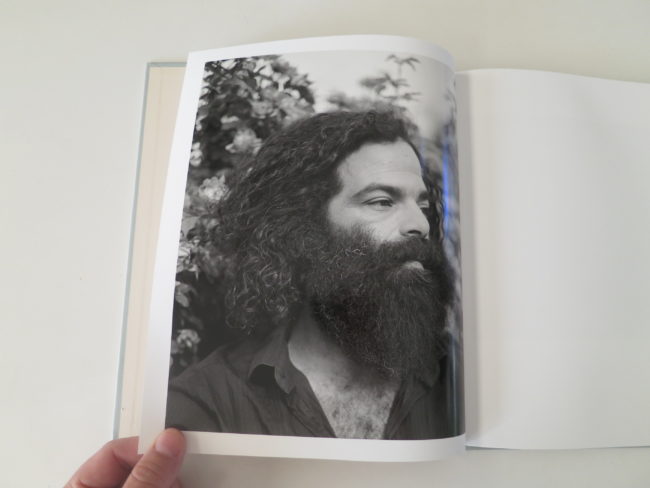

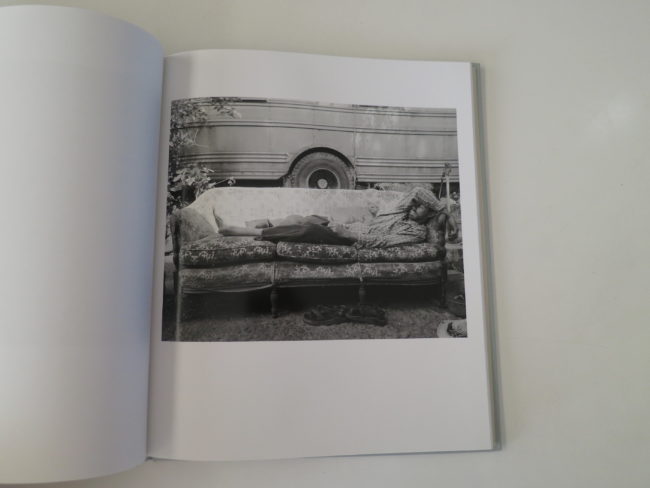

In some cases, like The Mesa community here in Taos, people live simply, in trailers, huts or teepees, out of choice. Because they’re turning their backs on mainstream culture.

Desert rat types.

They’re all over this region, in ways that create their own kind of anonymity.

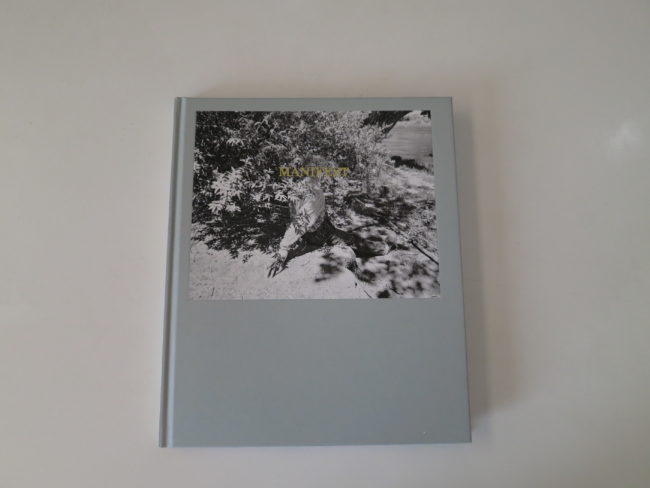

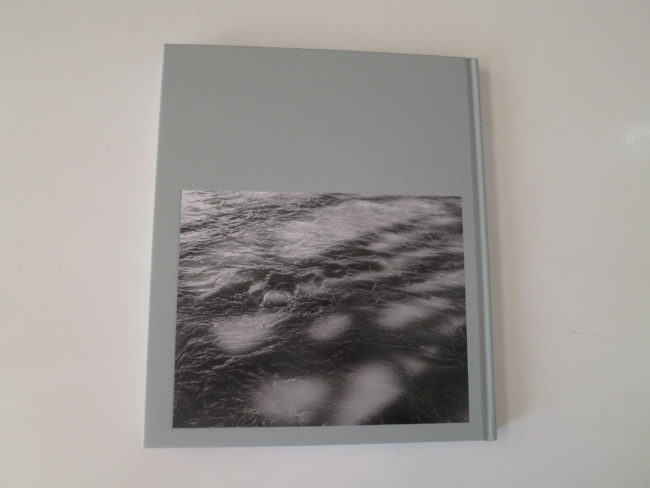

And ultimately, that’s why I liked “Manifest,” the new book by Kristine Potter, recently published by our friends at TBW books in Oakland.

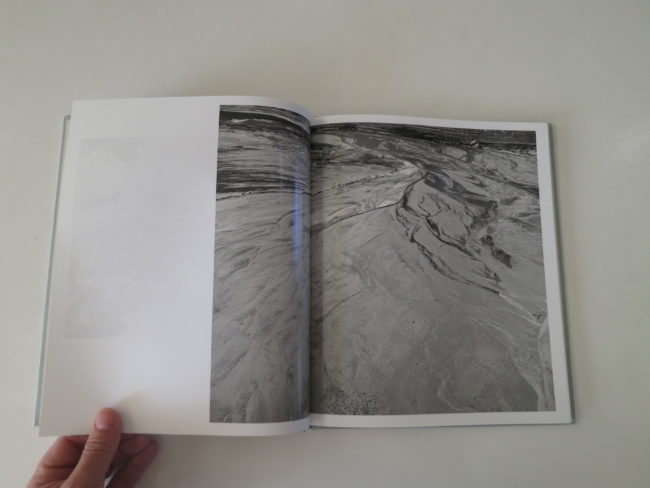

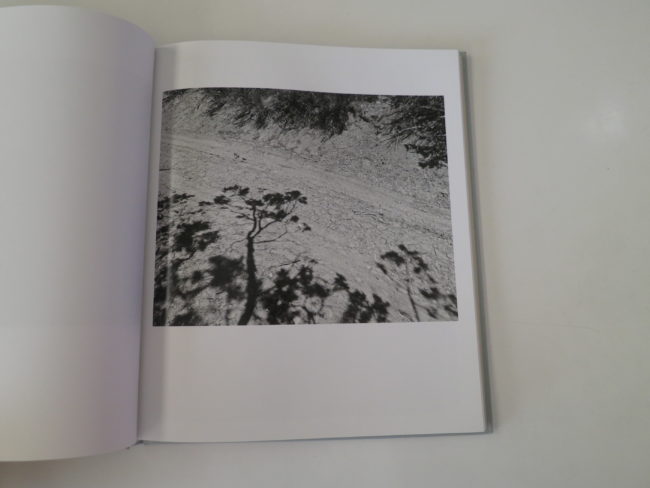

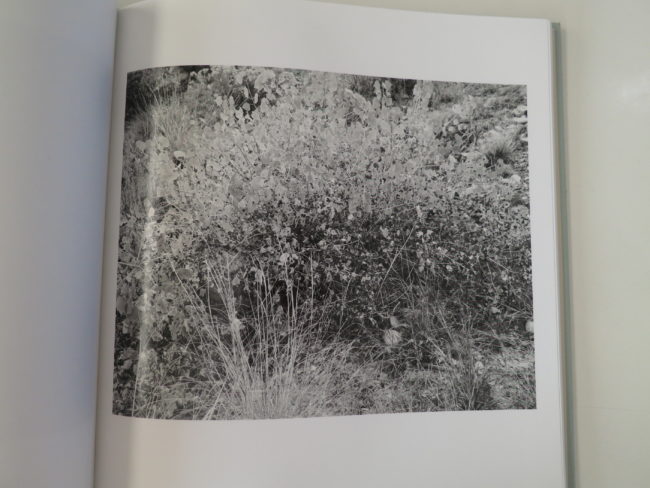

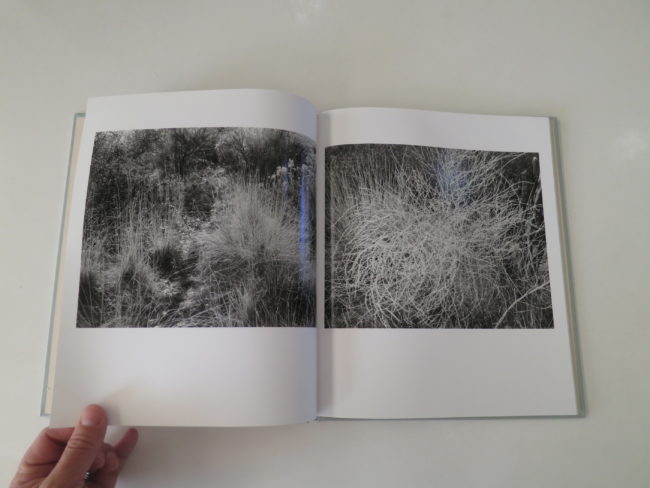

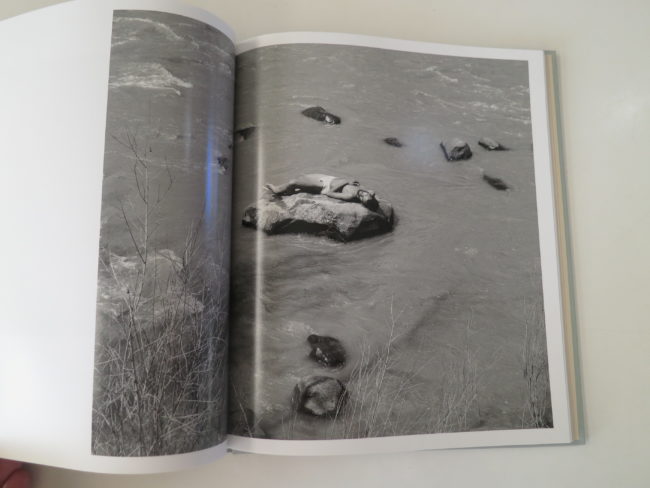

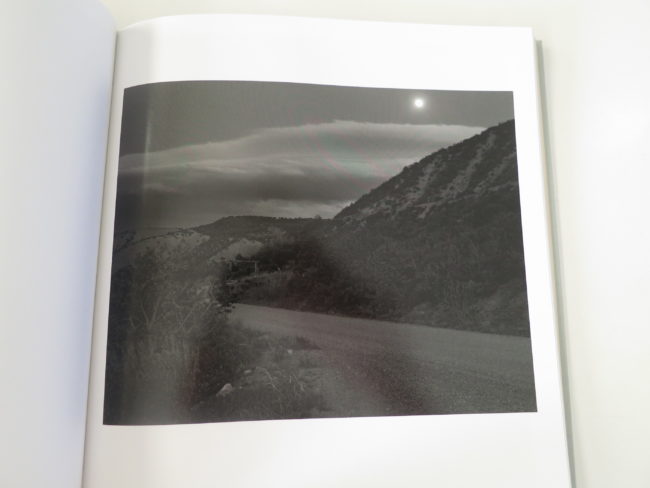

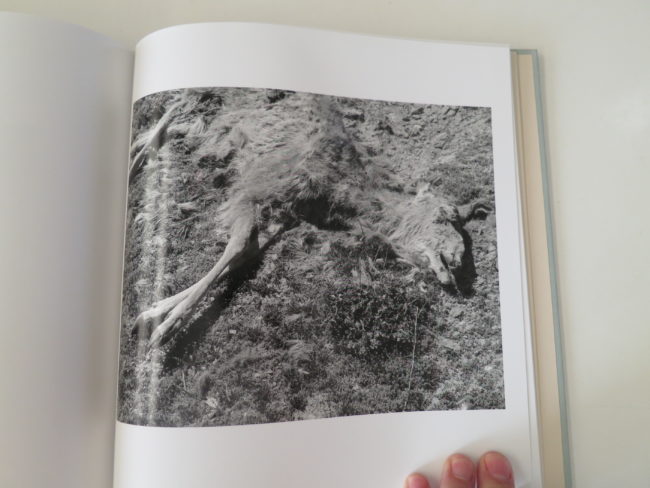

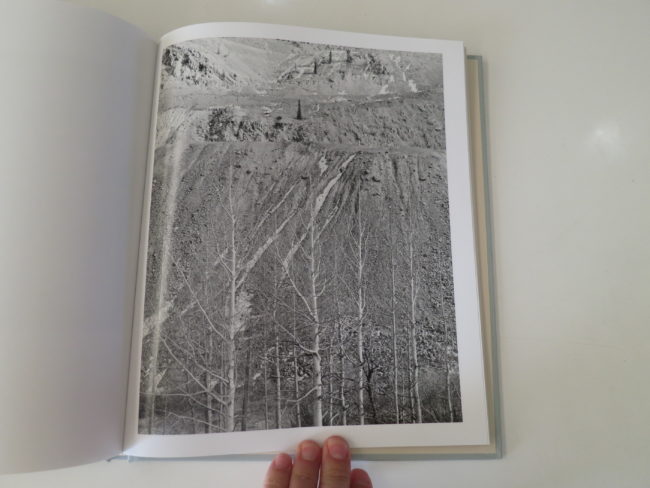

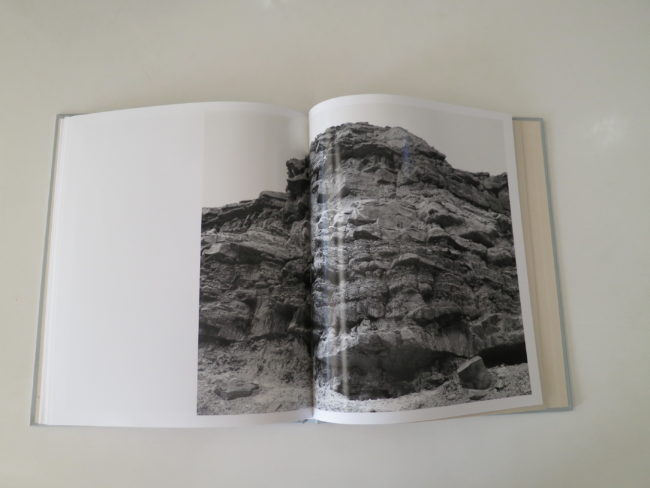

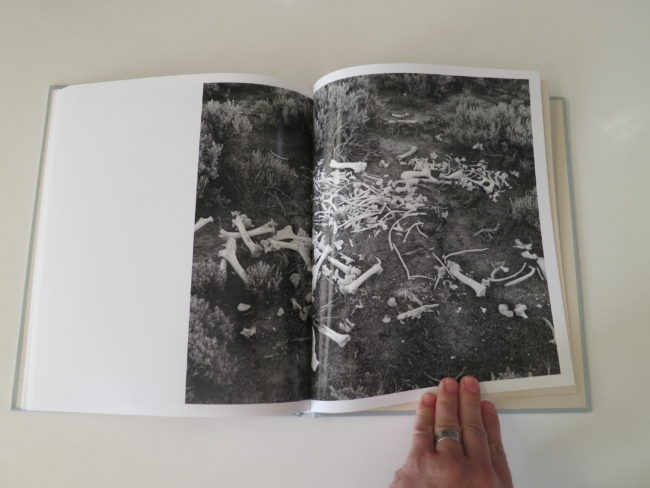

I appreciate this one because it manages to capture that sense of the general-ness of the light, and the heat, and the landscape.

Rocks and scrub.

Glare and sand.

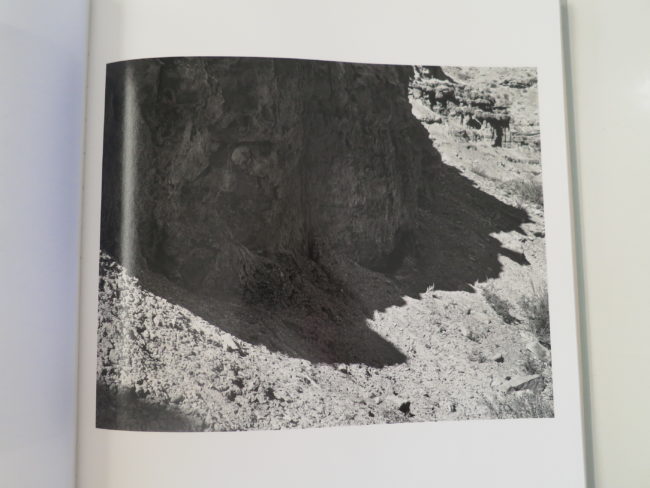

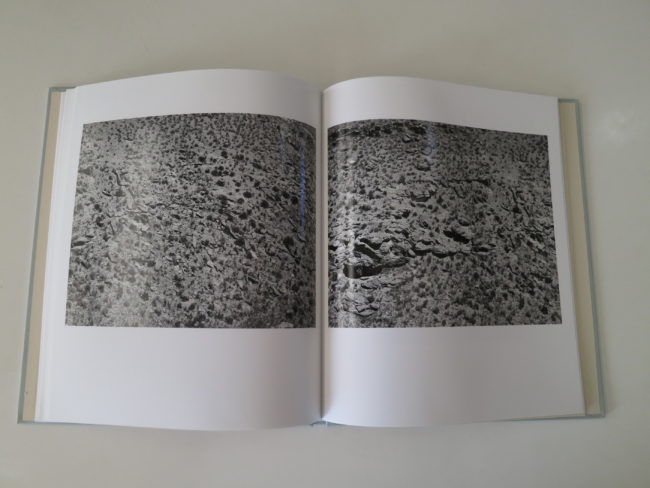

I also really appreciated the production values too. I rarely mention separations here, (the last I remember is the Henry Wessel book by Steidl,) but there was one image where the shadow detail in a rock face was so impressive that I almost gasped.

(I think that sentence would also draw the ire from our imaginary, aforementioned Trump voter.)

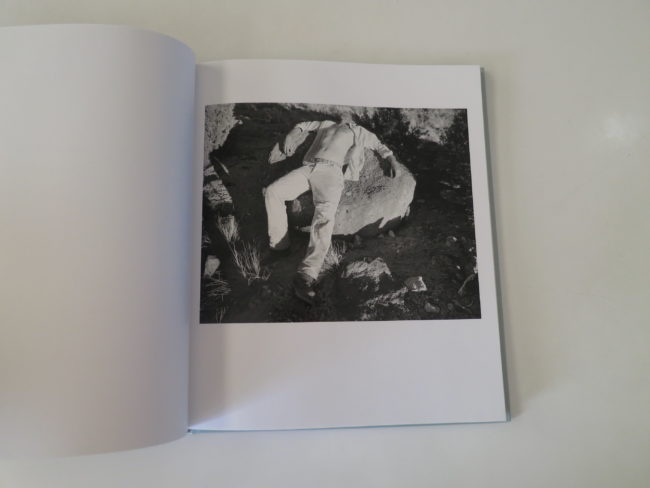

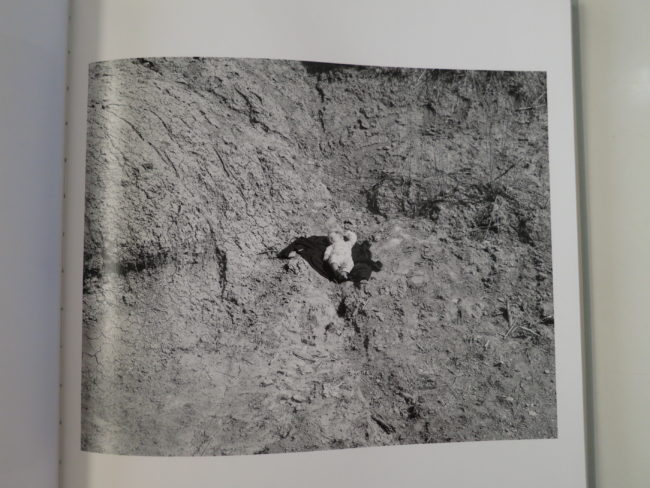

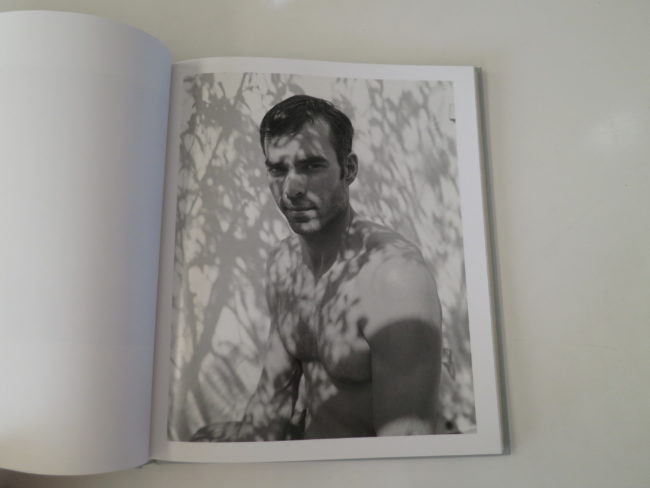

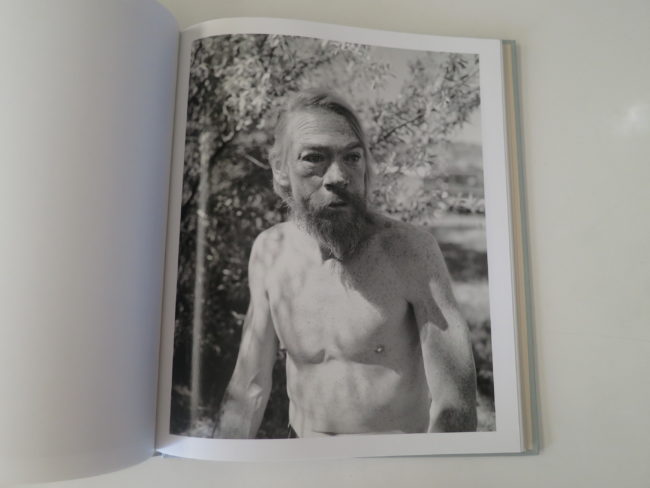

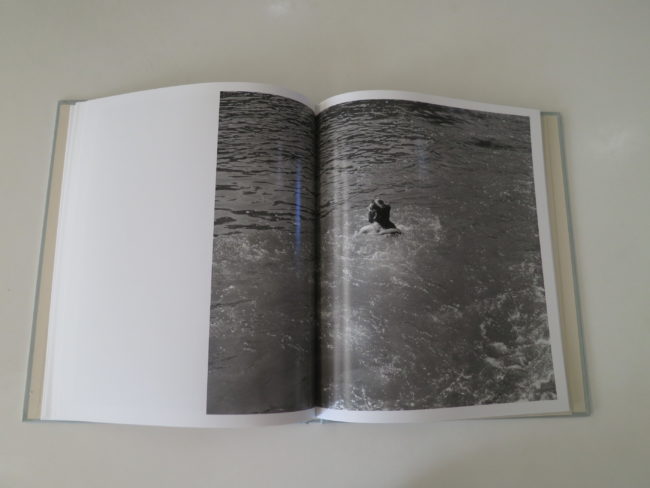

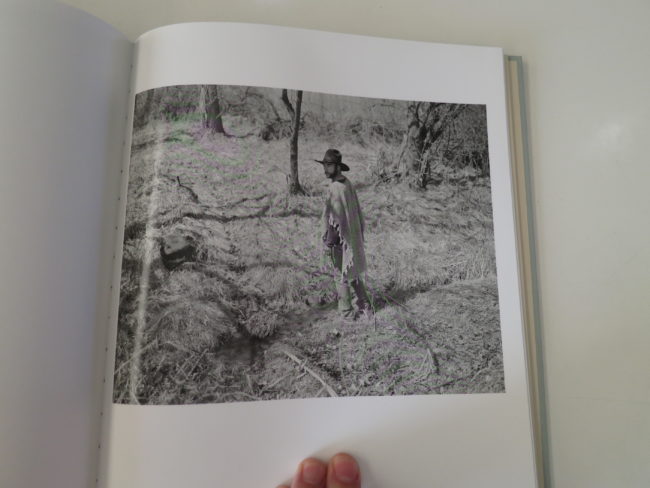

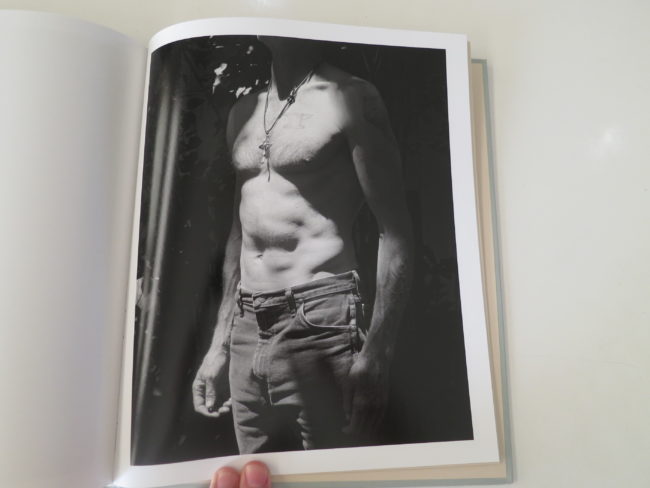

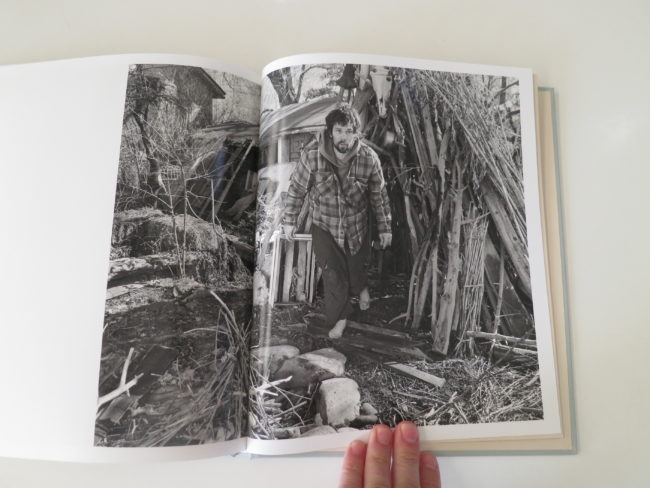

Then there are portraits of men, shirtless, which smack of the female gaze. (As the title of the book references Manifest Destiny.) These are cool too, and I get that they’re trying to be subversive, undercutting the traditional methods of representation, but even that feels a touch stale.

I made fun of the essay at the beginning today, (Sorry, Stanley,) but it mentions that Ms. Potter comes from a long line of Western families, and that she went to grad school at Yale. (The most infamous of photo-world mafias.)

It explains all the big-word-theory-driven sentences, and the attempt to try to make this work more conceptual, more theoretical than it really is.

When you go to Yale, you can’t say, “I like taking black and white photographs of the West.”

It has to be more than that. Justifications are created. It can’t just be, “I like it. It’s fun.” Or, “I want to make pictures that help me connect with the landscape of my lineage.”

Because those are the reasons I like this book. It keeps it real in ways I can respect, (and others I might mock,) but it definitely knows what it wants to be.

And it’s executed flawlessly.

Bottom Line: Dry, glaring, Western photos for a hot, dry summer

To purchase “Manifest” click here

If you would like to submit a book for potential review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com. We are particularly interested in submissions from female photographers, so that we may maintain a balanced program.

1 Comment

Must admit I remain somewhat confused by this project. Before reading it was about American cowboys, I initially thought it a book concerning homeless encampments. And it still strikes me as such. Does it delve at all into who these people are, their lifestyle, the disparity between the myth and the reality- or is the latter what the photos are meant to portray, and I’m a tad late on realizing?

Comments are closed for this article!