aPhotoEditor: Can you tell me how you came to work at GQ?

Dora Somosi: I studied art history in college, and I had aspirations of being a photographer, and my incredible, but very practical, Hungarian immigrant parents encouraged me to find a career that would make it possible for me to support myself. I didn’t want to abandon photography, though, so I got a job at Magnum Photos—the agency that owned the archive of a photographer I idolized, the Hungarian photojournalist Robert Capa. I like to say that Magnum was my graduate program in photography history. My time there overlapped with Natasha Lunn and Justin O’Neill, both currently brilliant photo directors, plus uber-agent Liz Leavitt, David Strettel of Dashwood Books, and Chris Boot of Aperture—all formidable influences at the start of my career in photography. It was a brilliant time to work there—because of my co-workers, of course, but even more because of Magnum’s 50 internationally renowned photographers. I got to work with them every day, and every day was hilarious and inspiring, working together as a cooperative, even if sometimes all those talented and strong-willed people in one place made it operate more like an uncooperative. After the experience of being an agent at Magnum, I knew I wanted to be on the assigning side of photography, and so I worked my way through magazine photo departments until I landed my then dream job as the Director of Photography at GQ, working with the design force, Fred Woodward.

aPE: GQ had such a strong reputation for photography during your tenure, can you tell me why it was such a focus for the magazine?

DS: Thank you for saying that. I worked on the visuals for GQ for a decade, and it means a lot to receive praise for all that I accomplished during my tenure there. I was fortunate to arrive at GQ when Jim Nelson was just starting out as editor-in-chief, and he invested a lot of money and attention on modernizing the GQ brand through the use of photography. He let me build a roster that could include a wide breadth of visual styles — Inez Van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, Martin Schoeller, Robert Polidori, Ben Lowy. He also gave me the latitude to develop new talent in fashion photography while also being as ambitious as possible with the biggest names in the industry.

aPE: After working with such talented photographers, what made you think you could become one?

DS: I didn’t set out to become a full-time photographer after I decided to leave GQ. It happened organically. I left in large part because I wanted to spend a lot more time with my family and more time outdoors. Maintaining work-life balance everyone talks about had become untenable for me. At the same time, I had identified myself for so long as a successful working woman, and my identity was completely bound up in that professional success. I felt really lost for that first year. That’s when I started taking my own photographs, documenting our family time together in upstate New York.

Once I developed a new body of work, I began sharing it with friends and trusted former colleagues. I feel lucky to be surrounded by so many strong women who appreciated the work and who backed up their words with assignments, shooting artists and interiors and travel destinations. It was incredible meeting all those other creative women who weren’t at corporate jobs, or on paths to their next job, and who were also successful and fulfilled. In my previous career, I’d come up through institutions, in the editorial and commercial fields. My evolution as a photographer has taken a very different path. My work is personal, and primarily landscape photography—pretty much the precise opposite of glossy shoots for which GQ is so renowned.

aPE: Tell me about your journey from hiring photographers to becoming one?

DS: I was introduced to black-and-white printing at an early age by my step-grandfather who was an accomplished amateur photographer in Hungary, where I was born. I remember pouring over his documentary photography dating back to World War II, in particular, the Russian occupation of Hungary. I’ve been taking photographs since high school, and I studied at ICP when it was still a dilapidated mansion on the Upper East Side. I published work in magazines and had one brief stint as a set photographer on low-budget movies, including one with Michael Showalter. And I took lots and lots of portraits of friends and other people I knew.

When I left magazines to go back to making my own pictures, it was a means to find an identity for myself, one that was just for me and wasn’t tied to being a mother or a wife or a picture editor. I had a successful side business consulting for photographers and independent brands, so I had the room to explore without the pressure of having to sell work.

I learned post production and master printing, and I educated myself about the technical side of making fine-art prints. I studied with Ben Gest at ICP—a brilliant fine art photographer and the most patient teacher I’ve ever known. I was taking landscapes and still lives, then printing them large scale. In the beginning, they were pure homages to nature—the healing power of the natural landscape, and a sort of love letter slash thank-you note to upstate New York for rescuing me at a crossroads in my life.

But then the 2016 election happened, and suddenly nothing looked as pretty to me anymore. I poured my feelings into my work, digitally manipulating the landscape, and once I started to mess with the images, I could feel my voice emerging as a photographer. That body of work resulted in my first show in Brooklyn, Altered Landscapes. I had a lot riding on that show—I was worried that if I didn’t sell any prints, it would be a clear sign that I should give up. Instead, my show nearly sold out, and my pieces are now in the collections of trustees from renowned art institutions, business leaders, accomplished interior designers wonderful former colleagues from GQ. That show gave me the confidence I needed to keep at it.

aPE: Can you reflect on what it feels like to now to be on the other side and pitch yourself as a photographer?

DS: Well, that has been a real revelation! I wish I’d been this vulnerable while I was a picture editor. To know what it feels like to spend years pouring your heart and soul into this collection of images, and then show them to someone who’ll spend maybe 15 minutes flipping through them with you. I now understand just how thick-skinned you have to be. I always think about my mentor, the late George Pitts, who I worked with at Vibe Magazine and who gave every photographer all his time, his care and his insight. I think his decency came in part because he had his own work, and like all of us he was surely a little fragile about how people reacted to it, and so he treated everyone’s photographs with the care he’d like to receive himself. I’m learning on the fly just how brave you have to be now just to create a body of work from scratch, but also share it with the world, in galleries, in meetings, on social media—everywhere. I’m also seeking out teaching opportunities at places like SVA, mentoring students and working with photographers to help them achieve their vision. When I was working in magazines, I didn’t have the luxury of that kind of time. Now I do and it helps me connect my experiences in agencies and magazines with my current practice.

aPE: Tell me about your show at NeueHouse in LA?

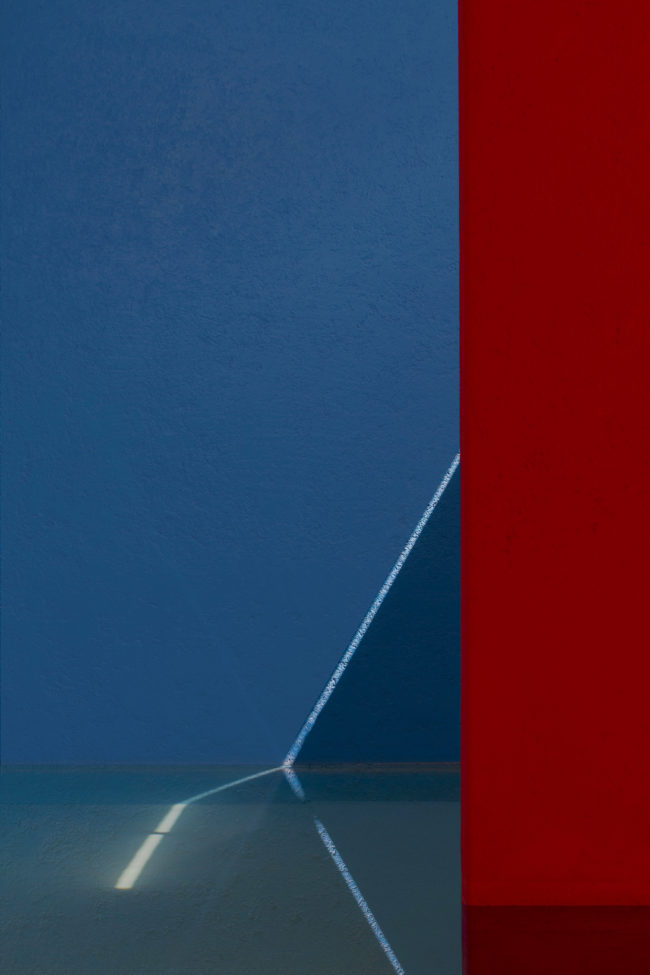

DS: This will be my second solo show, and this time I’m working with a curator and a whole team of people, which is very exciting. Making my photographs is pretty solitary work, so this is a welcome break from that—a chance to collaborate with other creative people on a larger show for a wider audience. This show will focus on a body of work I made in Mexico City. These images, like my other work, begin with a layer grounded in reality, in this case, architecture, and then through color collage, they build into a fantastical, hyper-real expression of my interaction with the city, its people, and its kinetic energy. There are strong influences of Josef Albers’ work in Mexico, the colors from Luis Barragán homes, and the Bauhaus movement.

The show will also highlight my floral work, which will also be on view at ICFF in May. This work has parallels to the Mexico City work in terms of its use of saturated colors, and the tondo format. The florals—records of moments both happy and sad—achieve an eerie sense of perfection, fragile and fleeting, whose authenticity is meant to feel dubious. The flowers, though ravishing in life as in death, serve as the vanitas: a reminder of the inevitability of change. I invite viewers to look with attention at such seductive natural beauty without forgetting all there is to lose. And finally, there will be a preview of photographs I am currently at work on—seascapes, meditations on the horizon inspired by Hiroshi Sugimoto. The simplicity of the seascapes is meant to draw the viewer’s attention to the building blocks of our existence, and the ease with which we can squander the most fundamental elements of life, water, and air.

The Color of Air, an exhibition of new and recent work exploring architectural and environmental abstraction will open at NeueHouse Hollywood on June 28, 2018.

See more of my work at dorasomosi.com

and through IG – @dorasomosiphotography