I’m not feeling very creative at the moment.

The sky is gray out my window, and the dreary light is making me lazy. In a perfect world, I’d get back in bed, pull the covers around me tight, and take a big fat nap.

But we don’t live in a perfect world.

I bitch and complain as much as the next guy, but in general, I’m aware of how good I have it. While life can turn on any given day, I’m healthy, have a beautiful family, and live in a wonderful place.

If I feel hunger, I go to the refrigerator and make myself some food. So in the grand scheme of things, I have little to complain about.

Living with comfort and security is the root of the American Dream. Without question, we take it for granted. It’s hard not to, as the micro-stresses of daily life add up, and in the aggregate make it difficult to maintain perspective.

As artists, we have a built-in stress relief mechanism, as long as we have the energy to use it. I’ve written many times that I taught abused teenagers for 10 years, and was able to see firsthand how creative outlets allowed them to channel the powerful emotions they have, in response to their tragic circumstances.

Art is its own form of therapy.

I knew my students had undergone horrific situations. As I wasn’t their therapist, I never asked for details. (It didn’t seem appropriate.) My wife, who is a therapist, and works with the same population, has heard frightening stories that would make most people reach for a bottle of whiskey.

Or a big fat joint.

She doesn’t tell me the details, because she’s not allowed. (It’s all confidential.) So she keeps it inside, and sometimes goes to therapy herself, but when things are really bad, I can see the stress energy wafting off her skin like the heat waves that rise from my old wood stove.

Frankly, it’s rare that we find ourselves inside someone else’s nightmare. Sure, some people like to get scared, and pay to watch a creepy movie.

But that’s fiction.

Occasionally, we find ourselves privy to someone else’s darkest secrets. Occasionally, we choose not to look away. (Even when it’s the stuff of pure darkness.)

In my six and half years writing this column, I’ve often shared that my favorite photobooks are experiential. They carefully consider how to unspool the thread of their narrative; how to engage an audience by divulging details in just the right way.

I love books that show me things I haven’t seen before, and give me insights I couldn’t otherwise access.

I’ve also admitted to being something of an Anglophile, as I’m addicted to English football, and wrote stories on this very blog about my remarkably joyous trips to London in 2012 and ’13.

It’s easy to idealize a place when you only see its slick surface. People do that with Taos all the time. They come here thinking it’s a quaint, little tourist mecca, with hip art galleries and magnificent nature.

But as I’ve said before, it’s the most hard-core place I’ve ever lived, and I did a three year stint in Brooklyn.

There are plenty of entertainment options that glamorize English gangsters, like the stylish “Peaky Blinders,” the several movies about the Krays, or (insert random Guy Richie movie here.)

But I just put down a photo book that made my head spin, in a good way, though its contents are shockingly awful. (The kind of awful that enlightens, not the kind that comes from poor execution.)

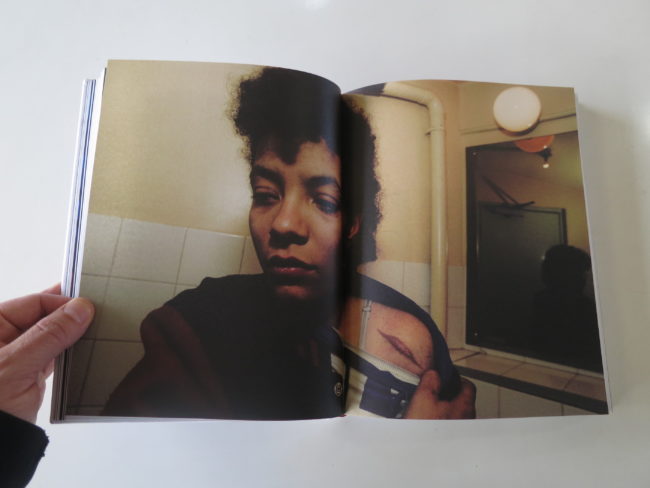

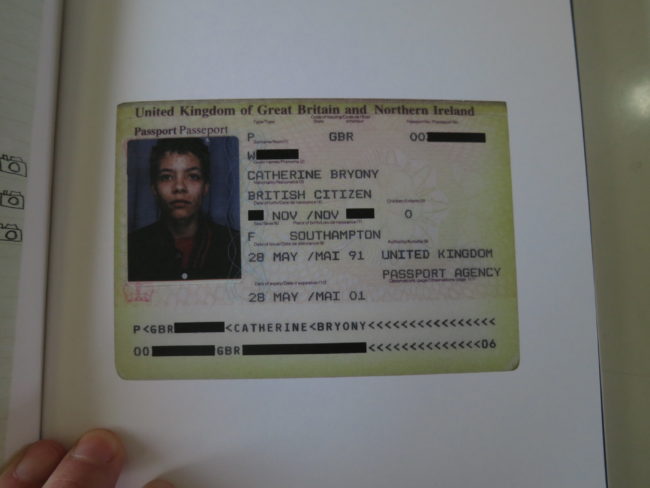

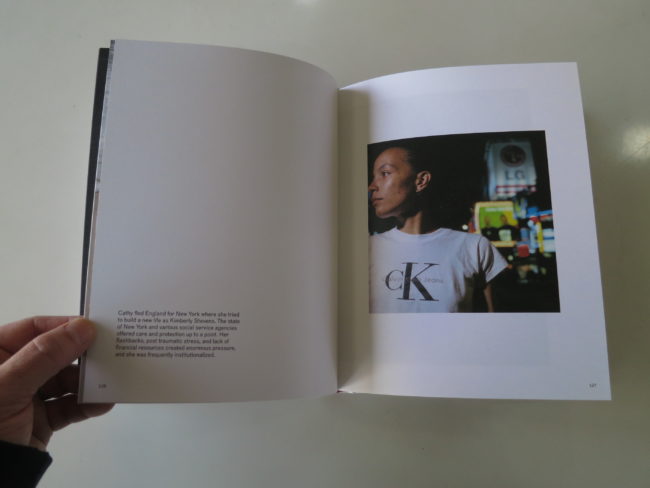

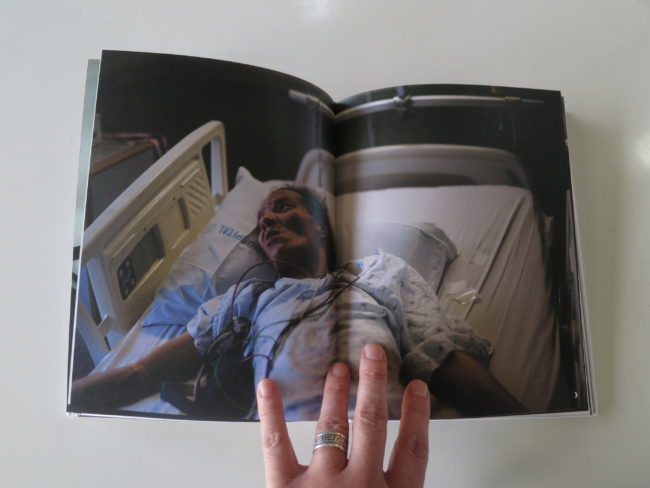

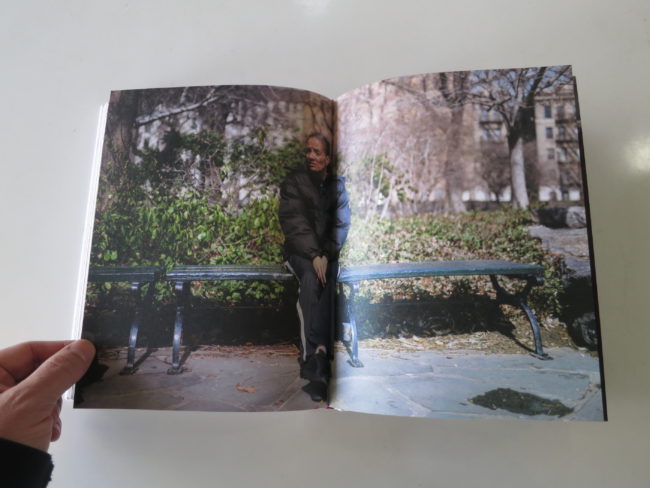

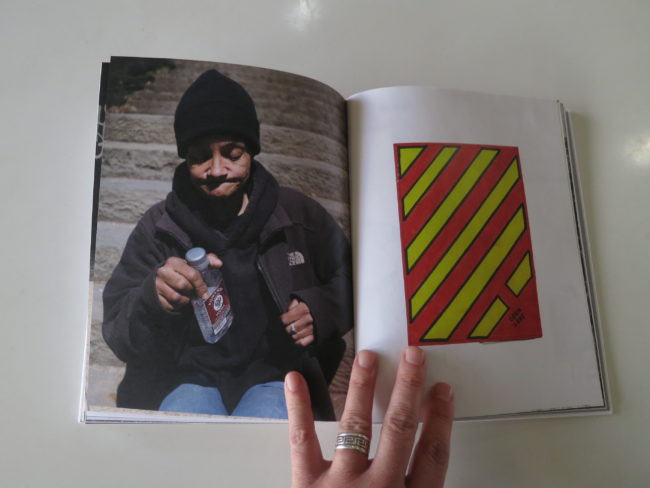

“An autobiography of Miss Wish” is a new book by Nina Berman, in conjunction with Kimberly Stevens, which was published in the fall by Kehrer Verlag in Germany. It’s generated a fair amount of positive press, and I feel fortunate to have been sent a copy a few months ago, when I was actively soliciting submissions from female artists.

(By the way, the first round of outreach was successful, but I’m down to my last two books by female photographers, so hopefully you guys can help spread the word to get a new batch of submissions for us.)

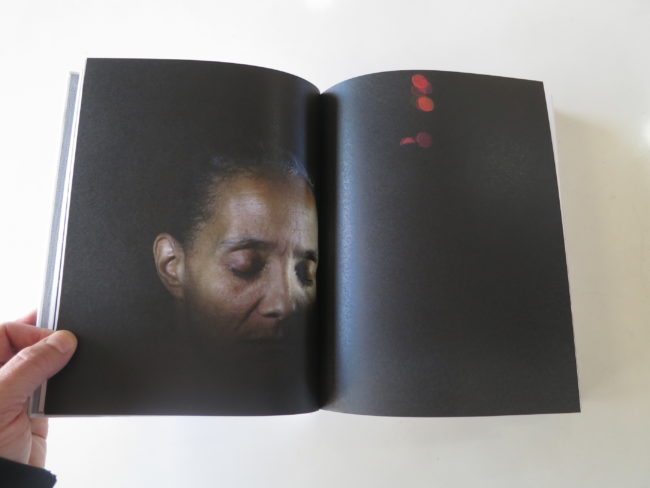

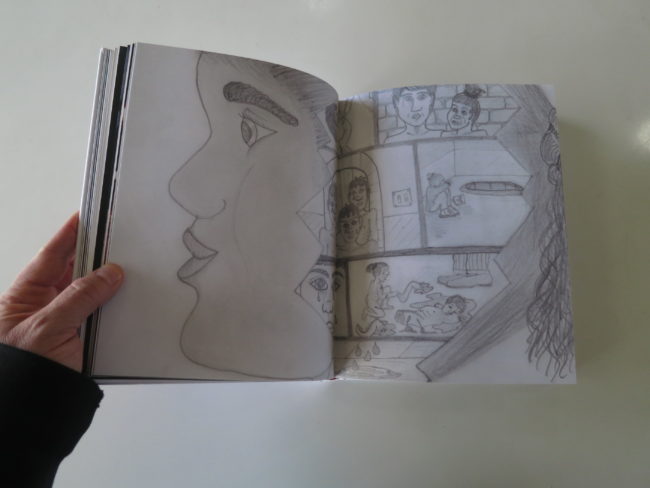

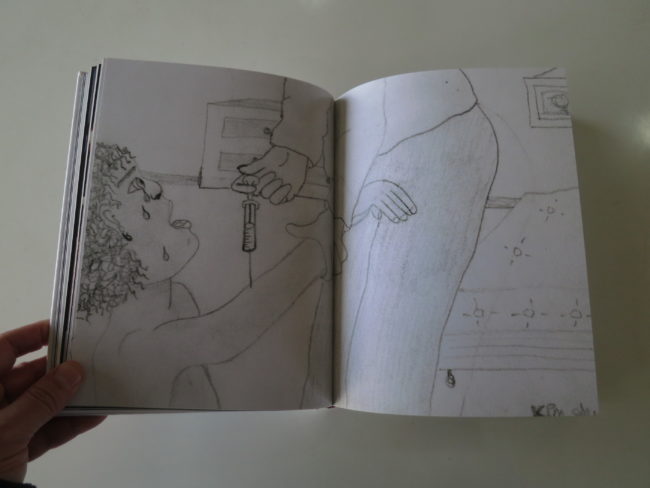

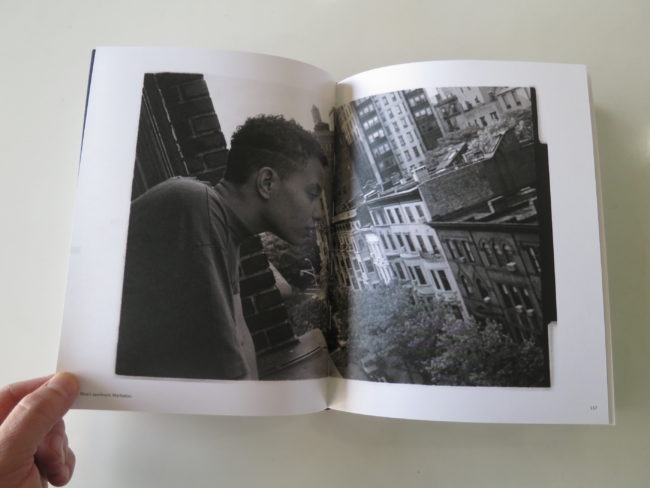

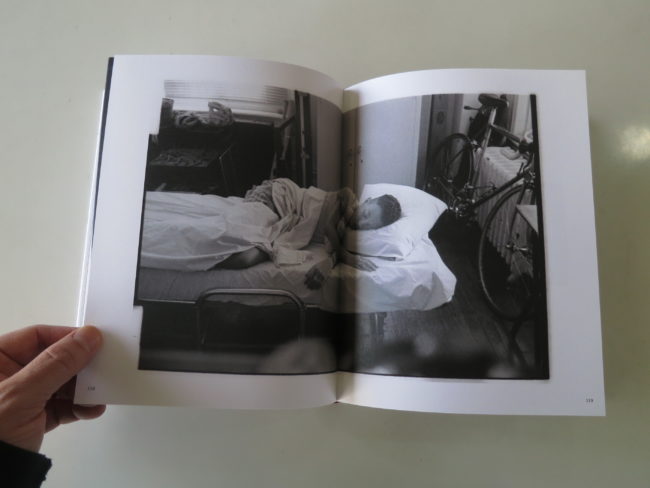

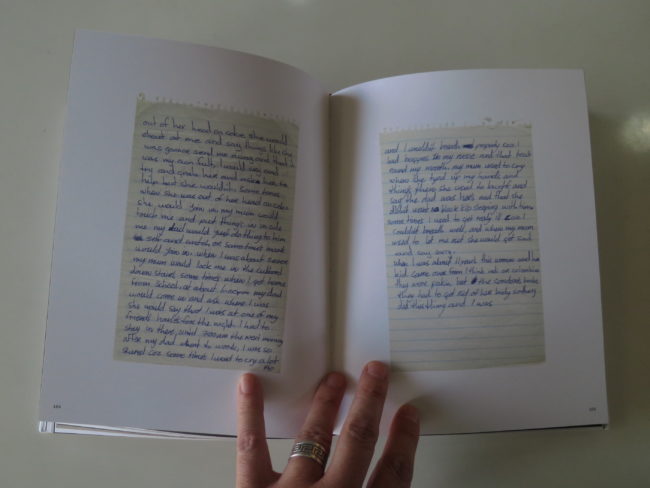

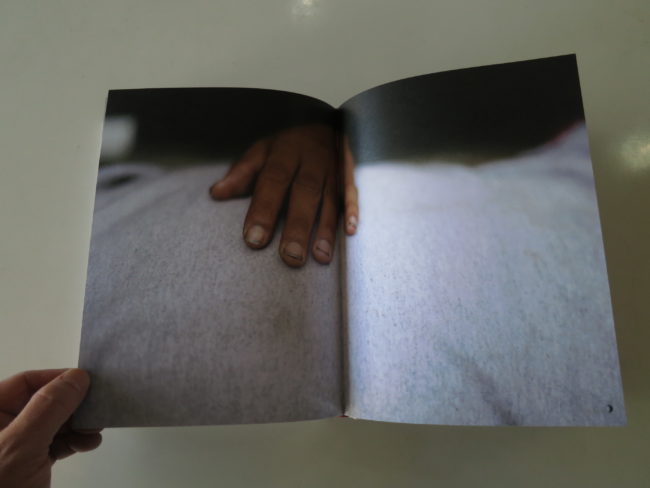

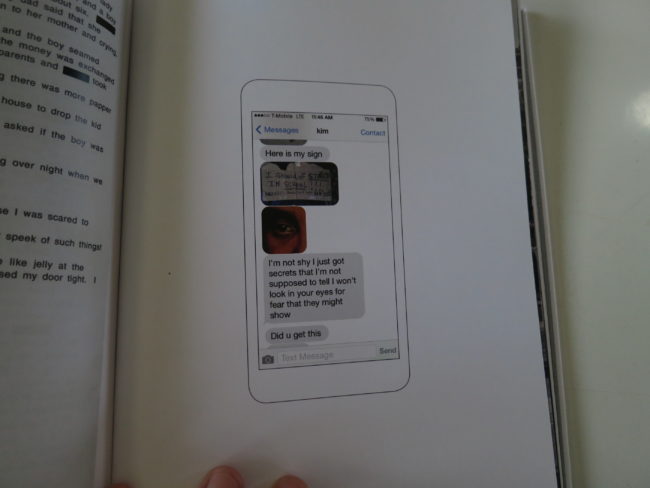

Kimberly Stevens is the latest name adopted by an Englishwoman who’s had as difficult a life as I’ve ever encountered. This book shares the kind of stories my wife keeps to herself. It’s hard to read what is presented here; to look at Nina Berman’s photographs, and Kimberly’s drawings and diary entries.

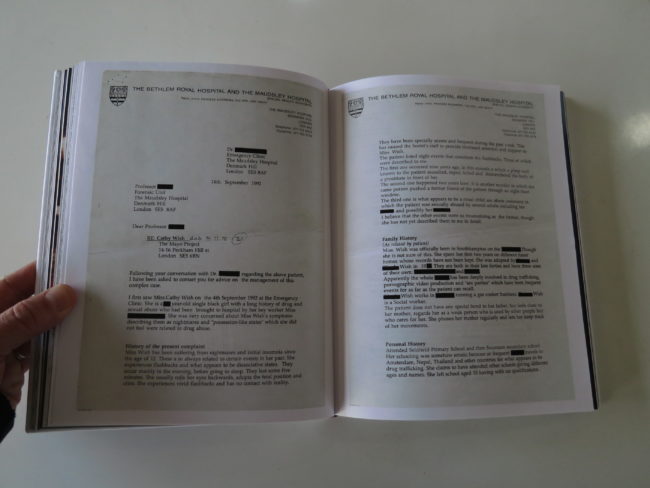

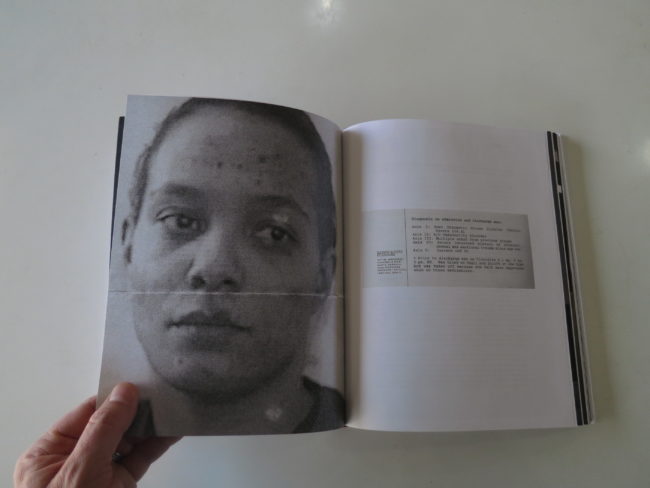

The shortest version is that Ms. Stevens was adopted at two into a family of violent, murderous, child-purchasing, sex traffickers. She was raped, tortured, and prostituted for her entire childhood. Even worse, the gang that ran her continued to kidnap her anytime anyone stepped in to help.

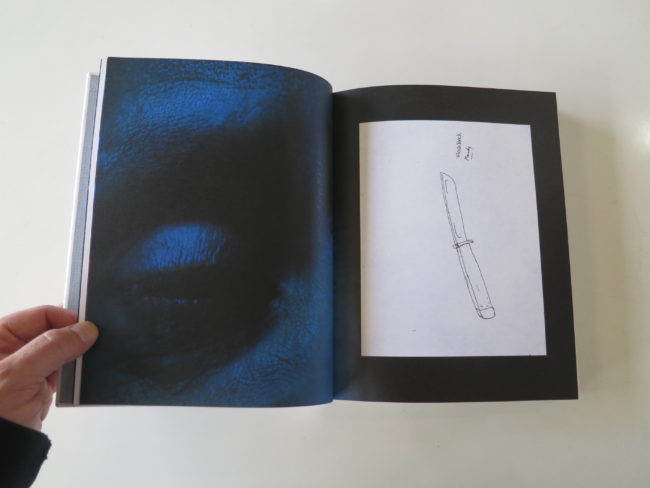

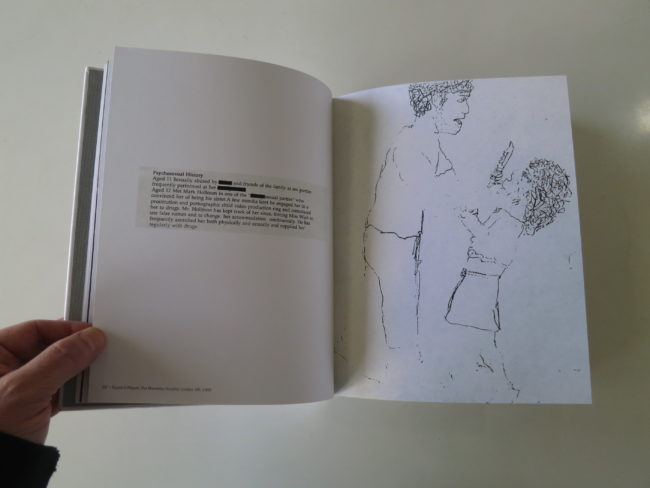

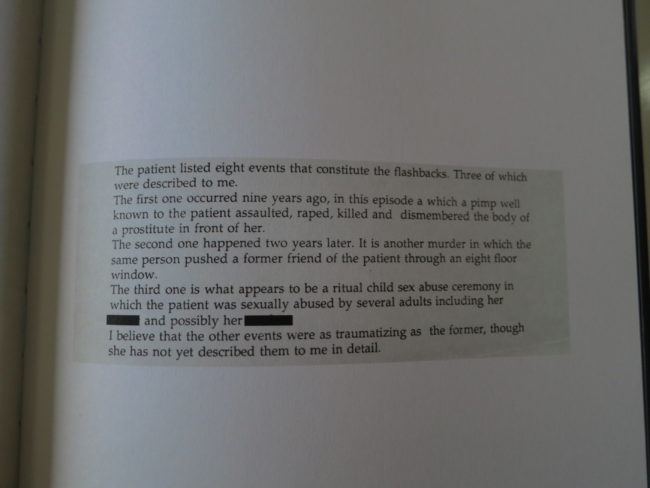

Lest you think I’m exaggerating, I’ll photograph the drawing she made of a dismemberment, part of a series of flashbacks that were symptoms of extreme mental illness brought on by Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

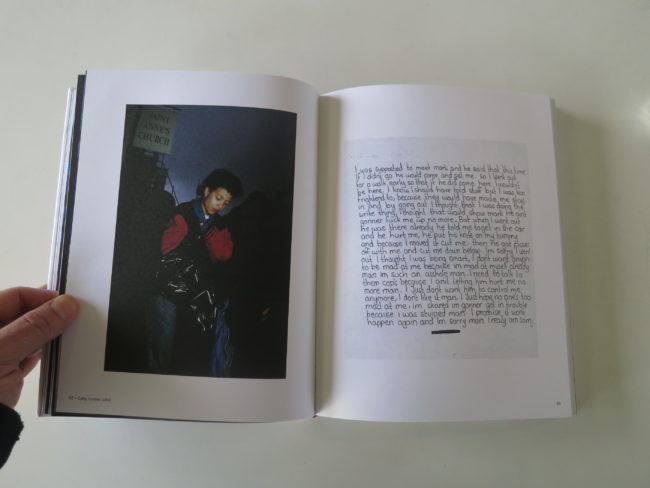

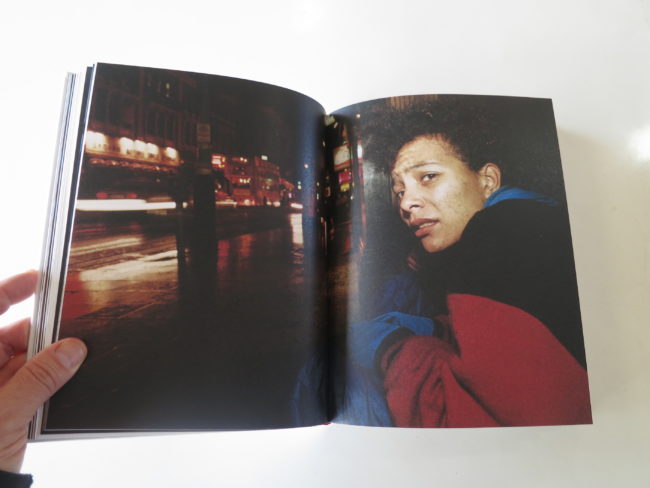

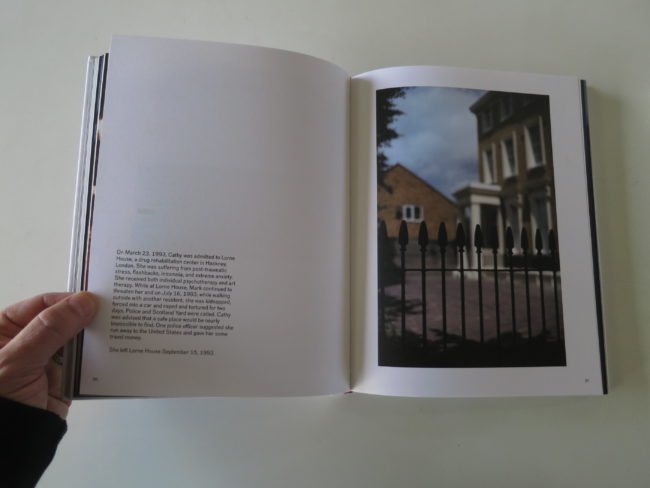

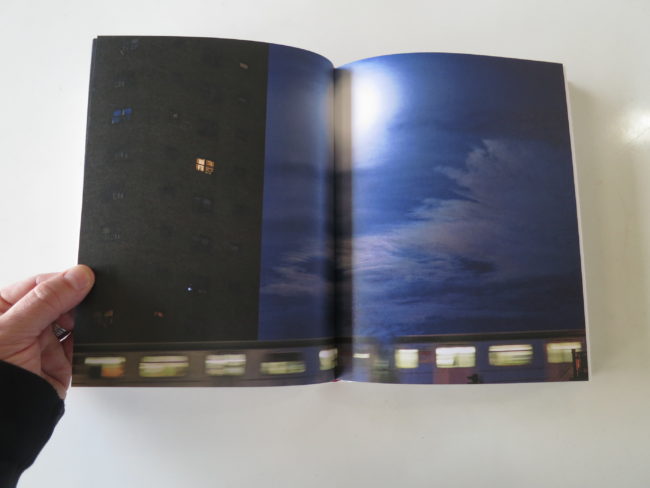

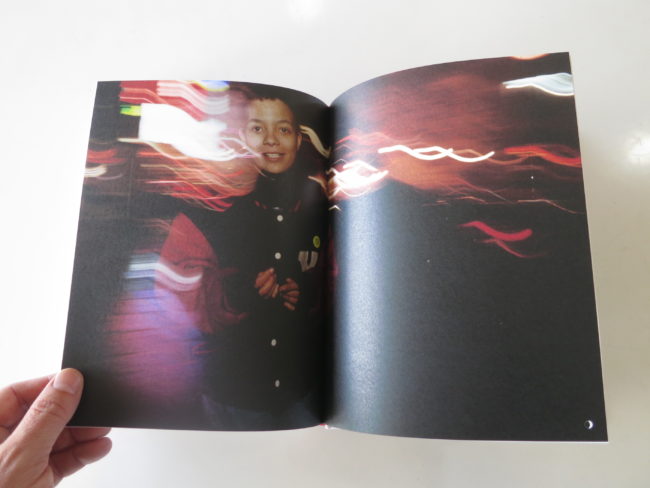

In what can only be described as a coincidence, or an act of God, Nina Berman bumped into Kimberly in the early 90s in London, when she was still going by the name of Cathy Wish. She photographed her roaming the city, and they struck a friendship.

As Kimberly’s captors were so well-connected that the police couldn’t protect her, an officer from Scotland Yard suggested she escape to America, and even gave her the money to buy a ticket.

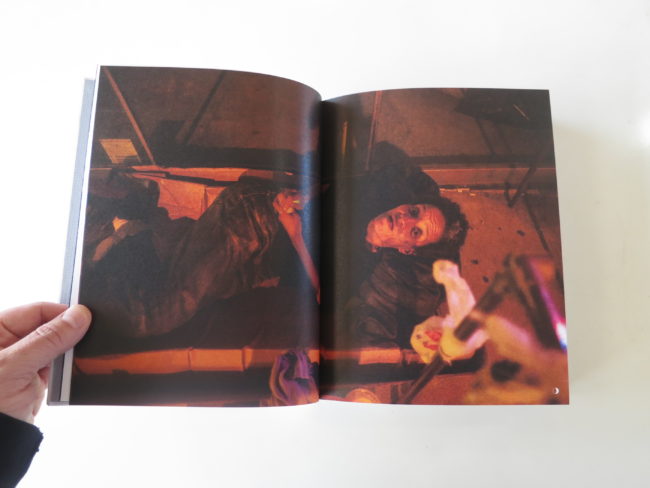

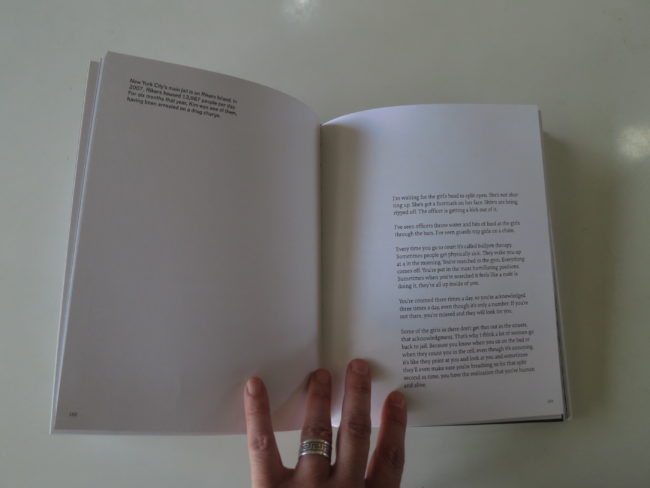

So she came to the United States, (the exact type of immigrant our current president despises,) and made a life for herself on the streets, in the shelters, jails and mental institutions of New York City.

Throughout, Kimberly has suffered from multiple personality disorder, suicidal tendencies, drug addiction, HIV, and dissociative fugue states.

(Like I said, this gives hard-core a new definition.)

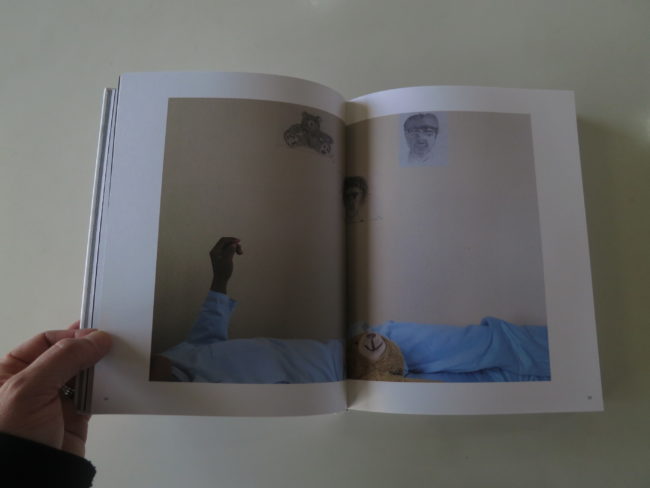

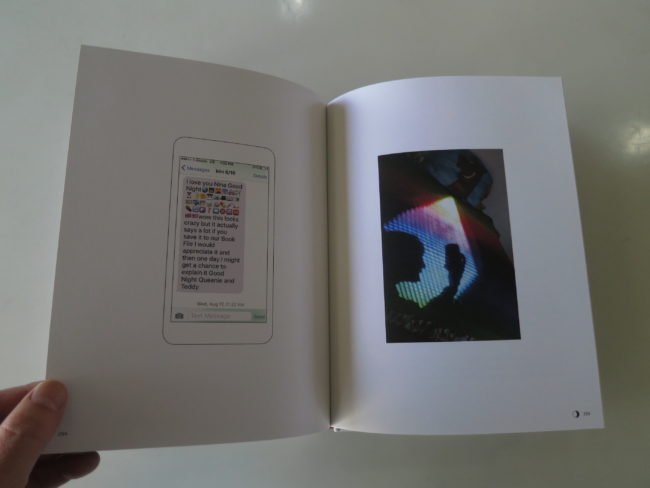

The book, which is remarkably well done, shares the story with us in a variety of ways. From medical reports to text messages, consistently interspersed with Ms. Berman’s documentary images, we’re given access to Kimberly Stevens’ life story.

Throughout her time in our country, Nina Berman proved to be her support system.

Her family.

Her rock.

I interviewed Nina Berman for this blog many years ago. She struck me as an extreme personality. You have to be, to somehow believe Kimberly Stevens could carve out a life worth living. That she wouldn’t be better off just jumping off a bridge, or out a window, both of which she tried to do.

Instead, they made this book as a testament to the indomitable spirit of the ultimate survivor.

As far as I’m concerned, photobooks don’t get much better than this.

Bottom line: A collaborative masterpiece

To purchase “An autobiography of Miss Wish,” click here

If you’d like to submit a book for potential review, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com

4 Comments

Wow… just wow.

Figured you’d like this one. It’s about as good as it gets.

Totally Mesmerizing.

Thanks for bringing it to light.

[…] so here, because it lead to reviews of Kathy Shorr’s “SHOT”, Nina Berman’s “An autobiography of Miss Wish,” and now “The Family Imprint: A Daughter’s Portrait of Love and Loss,” by Nancy […]

Comments are closed for this article!