St+Art / Sassoon Dock Art Project

Content Director and Photographer: Akshat Nauriyal

Assistant Photographer: Pranav Gohil

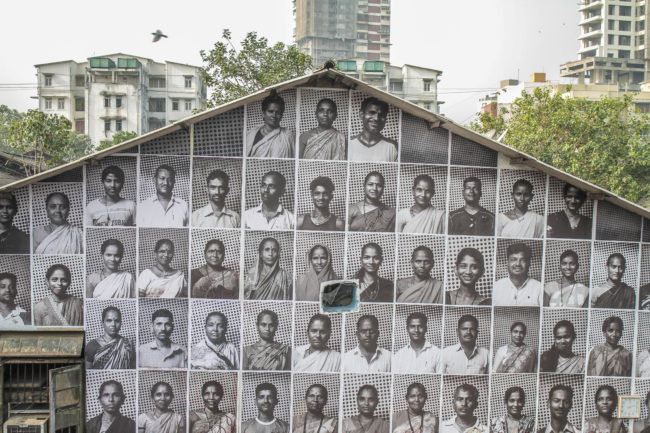

St+art Urban Art Festival has transformed Mumbai’s Sassoon docks Mumbai’s oldest fishing community into an exhibition space with graffiti and art installations. Their mantra is ‘Art for All’ aims to showcase art projects in public spaces making art accessible, removing the experience from conventional gallery space and embedding it within our cities making art truly democratic and for everyone. Arjun Bahl, co found and festival director said, “the whole idea was to bring art to a certain sect of the community who usually don’t interact with art.” A photo installation in association with the Inside Out Project covers the warehouse walls as you enter the show.

Started by French artist JR, the “Inside Out Project” celebrates local identities and stories using large-format street paste-ups. In this case, roughly 300 blown-up portraits of locals were pasted on the warehouse walls and shot by photographer and artist Akshat Nauriyal who is also a cofounder of the St+art India Foundation, along with assistance from Pranav Gohil.

“When we approached the dock workers for the Inside Out project, there was some mistrust. Many photographers and journalists had come before us and misrepresented the people, only focussing on the lack of hygiene and the indoctrination of children in the economy, while missing all the amazing things the place stood for. We got in touch with community leaders to help gain their trust and make the people understand the project through them. We created a pop-up studio in one of the empty rooms in the dock itself so we could maximize on the number of portraits we could make since the people all spent their day there working. Initially no one came, but slowly some people started tricking in. As word spread about the studio though, people started pouring in and eventually we made over 350 portraits of the various fishermen and women communities of the Sassoon dock,” says Akshat about the project.

Heidi: Tell us how this idea developed, I know you were poised to take a boat ride with one of the fishermen.

Akshat: Initially as part of my research I was excited about the prospect of going on a boat with the fishermen. I’ve always followed a gonzo approach to my stories and wanted to truly immerse myself in the lives of other people. I made friends with some fishermen who offered to take me with them. I got up at 4 am and prepared for my journey. It would be a hard and grueling experience and I wanted to be prepared for the worst so I carried supplies of extra batteries, water, power bank and even food, incase we got marooned in the middle of the sea.

Armed with all these and ready to go on the boat Pranva and I arrived at the dock only to be told that the fisherman was busy selling fish and hence would not be able to take us anymore. So with that my dreams of being a fisherman came crashing down. But instead of going back, I decided to spend the morning at the dock, my first of many such mornings and spent time talking to people and understanding the different layers in the micro economy. This would become an important part of my visual and content research.

I also immediately noticed was that the docks were dominated by women, dominant women. They were the peelers, porters, buyers and sellers. They were as fierce and assertive as the men around, most times even more. Which kind of also put into perspective how women are more than equals in shared public space and yet we cast this impression of the weaker sex upon them. This was a major takeaway from that days for me.

After many such mornings, I met with community leaders regularly to understand of the space. And what emerged was that the space had 3 main communities who were dominant in the I and had been so for decades. These were the Koli Fishermen (they went out to catch the fish) , the Banjaras (men help in hauling the fish off boats while he women help in peeling and transporting) and the Hindu Marathas (they cart the fish). These three communities would become the main focus of our project.

What surprised you the most about this project?

There were many surprises; from the complexities of the space which I experienced first hand and how different they were from everything I had researched online. Most of what I read before alluded to the Koli’s being the most significant community, almost the only significant community at the docks. But upon reaching and doing on ground research, the reality was a lot more different from what I had initially imagined. The reactions were also surprising. Most people were very happy with the project, many identifying their friends and relatives from the community. But the most surprising reaction was one day I was told that some Banjara ladies were unhappy with the project. I immediately went to the dock.

They had reservations on their photos being next to a man who was not their husband. I told them that when they work in the dock, they all work together – men and women as equals. In those moments it doesn’t matter if the man next to them is their husband or not, which is exactly what we wanted to represent through the paste-up. Eventually I even offered to remove the paste-up because if the people whom I intended to represent through the project were not happy with it, then the project was futile. All the ladies immediately asked me to continue and gave me their blessings.

How did you evolve creatively?

Documentary, as a format for me is a chance to have a unique experience. It is a way of getting access into people lives and scenarios. It is an insight into a completely different knowledge pool, of insight about life, which I try to access through the people and document- more as a means to understand how people perceive life and exist in the world around them, which I hope to learn from for my own life.

This project was a culmination of all the work I have done in my life in many different capacities. I started as a drummer playing drums for bands in the independent music scene in India. That led me to documenting many of the emerging subcultures I saw around me in Delhi more than a decade back, and that was done from within those communities as a part of the scenes . I’ve done portraiture and fashion work and also several ngo/ community based projects and eventually I founded this public art foundation. I feel in a way everything up till now was a learning process to be able to do this project.

I like my work to be a true representation of the people I document and hopefully I have been able to do so with this project. I have met many wonderful people as a result who have welcomed me into their lives giving me an insight into worlds I would never have access to, and the honest and genuine connections I have made will go with me through my life. The portraits may not stay forever, and may not really impact their lives directly. But for me, in a city of stars, where only celebrities are glorified on large hoardings, the memory of seeing their own face blown up on the facades of buildings they themselves work in, and inhabit, will hopefully be something they keep with them forever. In the city of Bollywood, where one usually has to be a celebrity or a famous person to be on a large size poster, the representation of the everyday workers of Sassoon was a way of acknowledging them and letting them know that they all matter and are of value and are the real stars, irrespective of their standing in society.