Caracas, Venezuela

Torre David, Caracas, Venezuela

Torre David, Caracas, Venezuela

Floating School, Makoko, Lagos, Nigeria by Kunlé Adeyemi

Floating School, Makoko, Lagos, Nigeria by Kunlé Adeyemi

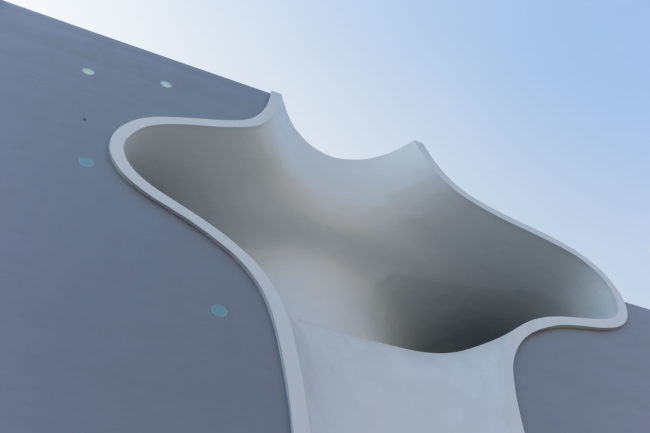

Heydar Aliyev, Baku, Azerbaijan by Zaha Hadid

Nanping Village, Anhui Provence, China

Pavilion, Shodoshima, Japan by Ruye Nishizawa

Sanmenxia, Henan Province, China

Sao Paulo, Brazil

Traditional Lobi Village, Northern Ghana

Four Freedoms Park, NY, USA

Iwan Baan

Heidi: Architectural Digest recently published a series of images honoring the 16th anniversary of September 11 attacks. Tell us why you approached that shot from an aerial perspective.

Iwan: Every time I’ve been in the air over New York I’ve made a point to go to that area and photograph the progress. When the monument and new World Trade Center were completely finished it was a very important moment . For me the best way to see how all the various parts of downtown fit together with the memorial, the new World Trade center and the transportation hub was from the air. This image was from my personal archive of this buildings progress.

By what means are you making the aerial photographs? Helicopter, drone, airplane?

Usually I do it by helicopter and I feel there is much more flexibility that way. With an aerial perspective, you see how a building sits in the context of a city or large environment , you can’t really get it with a drone because of the distance required, and you are much more limited in terms of cameras and lenses. The great thing with the aerial perspective and working together with a helicopter pilot is that you can really compose the images, putting foreground and background together to tell the story of a building’s larger significance within the context of the city. I also have a drone but it’s used as a last resort when there’s no way to get a helicopter, or on small projects where I don’t need to be so far away. I really prefer working from helicopters

With building requirements and criteria becoming more and more stringent how do you stay true to the fundamentals of your photographic look and style and do you find this a creative challenge?

In the Western world with building regulations and material limitations it does become more difficult to make something truly unique in terms of architecture; to define a new language in terms of creating buildings.

As a photographer I come in at the end of the building trajectory with the structure already completed and functioning, so in a way the surprise of buildings and projects in the West is often diminished because more and more the buildings seem like just a set of components put together from a standard catalog of materials. I think that’s a big challenge for architects in the West, and one of the great things of working in other places where building regulations are much less strict, and architects can really experiment with a wider range of materials. In terms of experiencing and documenting these places it can be a lot more interesting visually, which definitely affects my work.

What was it about the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House in Taiwan that you found so intriguing and exciting?

It was built by the Japanese architect, Toyo Ito, and the outside is basically a very simple rectangular box, but none of the interior walls are straight and every dimension is transformed by the way the walls move throughout the space, they create space and any leftover space is used by it’s neighboring space. The interior world is completely fluid where floors become walls become ceilings, it almost like your stepping into the womb of a living entity. All these curving walls are there for a reason, they’re structural, meaning they are there to hold up the building, not just because of the design and it almost gives it a spiritual meaning.

It took years and years to build with the process being extremely radical, and the city government had a big challenge to outfit it properly, to help it become the incredible space it is.

National Taichung Theater, Taiwan by Toyo Ito

I enjoyed the interactive map on your site that chronicles all your projects. Is this a tool to signify to the viewer the breadth of your travel?

It’s also a way to show some of the small projects I initiate myself alongside the large public building projects centered in the capitals of the world. People may know my work from the more high profile projects, but there are many smaller projects that may be a bit more under the radar, some in developing countries and those can make big contributions locally where there are very few resources, and the need for these types of projects may be even greater. I also treat all the projects in the same way with my photographic process, and all the projects I take on are a kind of “sign of the times” where we mostly live in urban built-up environments these days. The world is one big place and I think this map helps bring the projects all together in a visual way, along with the way I work and how I show the work.

I read you lost your studio space to a fire a while back. Has it influenced your intense travel losing that personal space.

I was away working in the U.S. at the time it burned down and had been working in the intense travel style for six or seven years already. Basically everything I really needed in my whole life was already in the suitcase with me. When I learned of the fire I just went back to Amsterdam briefly to take care of some insurance things and look at the mess, but there was nothing more I could do, everything was gone and the things I really needed I already had with me so I just made the quick stopover and didn’t think much more about it.

Luckily the way we work these days, and for the last 15 years, my digital archive has been stored off site so in a way I was lucky. Colleagues from older generations where similar things happened with flood or fire have lost their entire archives since it was all physical with transparencies and negatives.

Eventually the space was rebuilt. A the time it didn’t really affect me much personally, maybe even pushed the travel to the next level for those two or three years, forgetting about having my own place and just living in hotels full time.

What kind of internal responsibility comes with your accolades of being one of the most influential architectural photographers of the 21st century?

I try to stay true to my own beliefs and take on projects I believe are making a larger impact in a city or built environment or push the boundary of architecture and new spaces. It doesn’t have to be the most beautiful thing, it can just be like a big intervention in the dynamic of a place. I think what I was trying to say earlier too is the projects need to be a sign of the times we live in and what kind of significance it has on the built environment. That’s also why I take on very few private projects like houses. I’m more interested in larger public or cultural projects that have a significance for a city, that help define a city or environment.

Photograph by Jonas Ericsson

Do you feel that buildings and space have spirit?

I think so. (chuckles) I think a good architect can definitely make a very spirited place, one that evokes imagination in people. That’s what I try to get across in my photography too, and why I include the context and people. I feel when it’s a truly new environment that an architect has dreamt up people respond to that in a different way, an emotional way, so I try to capture that essence in my photographs.

There really are new places to be discovered in the built up and dreamed up environment that architects put into a city, helping evoke a lot of imagination and spirit.

1 Comment

[…] A Photo Editor: The Daily Edit – Iwan Baan: Architectural Digest […]

Comments are closed for this article!