When I came home and announced I like Texas, my father looked as if I’d declared myself Nazi. The shock was real, even if the anger was feigned.

Negative impressions of Texas run deep here in New Mexico, as we encounter the flashier, private-tour-bus-driving Texan tourists each summer. Like any bias, my own personal prejudices were hard to maintain, once I started visiting the state a few years ago.

This time I wanted to check out Dallas, since even Texans like to mock the place. I figured if Houston, Marfa and Austin were cool, maybe Dallas was too, in an under-the-radar kind of way.

Can’t exactly report I found the city charming; all concrete and highway onramps. But I was shown some pretty fantastic hospitality, by photographer Debora Hunter, and met friendly and smart members of the local art community as well. (Which made the detour worth it.)

And big shout out to the Austin Photo Crew, ably led by Sol Neelman. A heap of photographers came out on a Sunday night to drink beer, eat pizza, and catch up. They assured me it was nothing special, as their group, rolling 50 deep, meets up each month to drink, talk shop, and play skeeball in town.

I’ve already extolled the virtues of Ft. Worth, with the Kimbell and Amon Carter Museums being free all the time. (And the Modern on Sundays.) But why were they so great?

As you know, I love to be surprised. To be blown away by things I’ve never seen before. The Kimbell, with its top-shelf collection of global masterpieces, let me revisit many artists I love dearly. (Cezanne, Mondrian, Picasso.)

But there’s one art piece I’m still thinking about today. Can’t stop talking about it, really, because I’ve never seen anything like it, and doubt I will again.

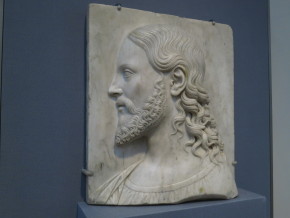

“Christ the Redeemer,” by Tullio Lombardo, a Venetian, was dated between 1500-20. It’s a stunning, white-marble, profile sculpture of Jesus, in half-relief. A genuine Renaissance masterpiece, one of only two of his sculptures in the United States.

The object’s orbit drew me in with haste, like the smell of fresh baked pizza. The detail work! Incising stone like that! Into hair! Creating those types of repetitive patterns?

Unfathomable!

The technique, the mastery of the process, allows the piece to take on energy. The vibrations from the patterning, the solidity of the stone, and beauty of the color, it all comes together to create a calm, visceral energy in the immediate vicinity.

I must have stayed there 5 minutes, but it could have been an hour. I simply lost myself in wonder.

That’s why tens of millions of people continue to go back to art museums every year. It’s easy to lose yourself in a movie. The sound, the scale, the visuals, they combine to build an immersive experience. Video games too.

But a sculpture sits still in space.

People bump into you.

The security guard asks you to please step back. Reality is all around, in 3 dimensions.

The best paintings, sculptures, photographs, they work so well that they allow us to jump the mundane turnstiles of regular life. It’s a big ask, I know, but that’s why I think we should always take the opportunity to visit with genius, when we can.

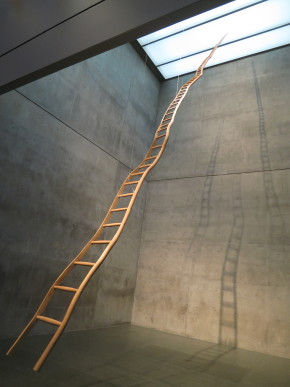

There was a Martin Puryear sculpture at the Modern that was equally brilliant, in its own way. I first found it from above, as it occupies multiple stories, and couldn’t believe the way it fit the gallery. Slowly receding up into space, diverging with its multiple shadows.

No wall card meant I had to ask around, and was told the artist info was down below, on the first floor. So I sprinted through the museum, (or at least power-walked, elbows pumping,) until I found its point of origin.

Breathtaking.

Beautiful.

Totemic.

Someone told me, later in my trip, that the piece had been designed for the space.

I believe it.

Days later, I’d find the same phenomenon at the Menil Collection in Houston. (My second favorite art space in the US.) It was an insanely excellent, 60 foot long painting by Cy Twombly, in the mini-museum they have of his work. When I asked the security guard how it could fit so snugly, she said the building had been designed around the painting.

Why is that relevant?

Maybe it’s not, but it seems like a part of the Texas Zeitgeist. Exorbitant amounts of money, an important if fairly recent history, and a culture that’s trying to catch up with global mega-cities that have hundreds of years of head starts. (There were cranes everywhere in Dallas. Always a sign of growth and ambition.)

By the time I got to FotoFest, half-way into my trip, I was pretty worn out. This was not going to be one of those events where I got to drink, party, and chat all night long.

No sir.

I stayed off-site from the event, in a little Airbnb studio that smelled like wet dog. (But thankfully came with an electric air freshener.) I made sure to get a good night’s sleep each evening, which I recommend, and took walks each day, to counteract the effects of all that recycled, conference-room air.

Normally, I’d have a slate of articles about the best work I saw. But as I was showing my own work, I didn’t have the same time to look at other people’s portfolios. Nor did a lot of projects jump out at me during my brief tour of the portfolio walk.

There are always a few people that have the “it” vibe at an event like this. Always happens. This time, Mahtab Hussain, from England, had the work people raved about, with his series “You Get Me?” I saw his pictures on the wall of one of the attendant FotoFest exhibitions, and was sucked in immediately.

He photographs young members of the disaffected Muslim community in England, where he grew up. These are the type of razor-sharp, incisive, taut, personal portraits that give photography a good name. Beyond that, of course, they’re as topical as Molenbeek, so Mahtab has that going for him as well.

Meghann Riepenhoff, another exhibiting artist, also had the buzz. She works with cyanotypes, which are having a moment, and makes pictures in the hand-made, of-the-Earth style embraced by her fellow West Coast photographers Matthew Brandt, John Chiara, and Chris McCaw.

Her installation, which I also saw on the wall, was pretty excellent. Furthermore, it didn’t look like other peoples’ pictures.

What’s the lesson here?

If you can get your photographs to a place where they are technically excellent, aesthetically pleasing, speaking to ideas that are important to you, relatively original, and relevant to contemporary issues: you might blow up at FotoFest.

I was also pretty impressed by Peter DiCampo’s new work, which he showed me one day. Peter runs an Instagram feed called Everyday Africa, of which you might have heard. The way he spoke about his project, built on the back of his own experience in the Peace Corps in Africa, reflected a fatalistic but humorous cynicism. He’s genuinely conflicted about the role of Western Aid in Africa, and it gave the pictures, as well as the narrative, a more nuanced take on do-gooding than I’m used to hearing.

Priya Kambli, of whom I’ve written before, also showed me some pictures that stuck in my brain. She’s always worked with historical, family imagery in her practice, but this time, she had images in which she had clearly “destroyed” or altered the source material, which then became her work. (Mostly by stippling little pin holes through old photos)

She admitted to me, and a couple of people who were looking, that she hadn’t scanned the originals before she attacked them. The others were mortified.

How could she not scan them first?

You can’t do that!

It’s sacrilegious!

I disagreed. There was a real tension to the pictures, and I thought part of that was due to the way Priya was out there without training wheels. She committed to the work, risked destroying important parts of her history, in order to make something better.

Something new.

Which is why I left for this big Texas road-trip in the first place. To see new things. To meet new people. To bring some fresh energy into my little Taos bubble.

Mission accomplished.