Marie Claire

Market and Accessories Director: Kyle Anderson

Fashion Director: Nina Garcia

Editor and Chief: Anne Fulenwider

Photo Director: James Morris

Photographer: Mitch Feinberg

Heidi: How did this project evolve?

Mitch: I have a wonderful relationship with Marie Claire. It is one of the few American fashion magazines that treat fashion still life pages as an opportunity to advance passionate editorial views on accessories and not simply as a vehicle to please advertisers. Their Market and Accessories Director Kyle Anderson, Fashion Director Nina Garcia and Editor and Chief Anne Fulenwider all take a direct interest in demanding that the pages are strong and fresh. For a still life photographer, this is a thrilling context in which to make new work.

Months before a final art due date, Kyle sends me jpegs of the next accessories story. The story subject might be based on a color, a design direction, materials or a cultural reference. It’s usually my responsibility to come up with a visual solution, although occasionally he or someone else will have a few suggestions. I pitch just one idea, including swipes from industrial sites or stores that refer to the environments I want to create. I do not like to make drawings or send “finished” images — it is better to keep things loose so that I have room for spontaneity. Once I send the pitch everyone weighs in and we go from there.

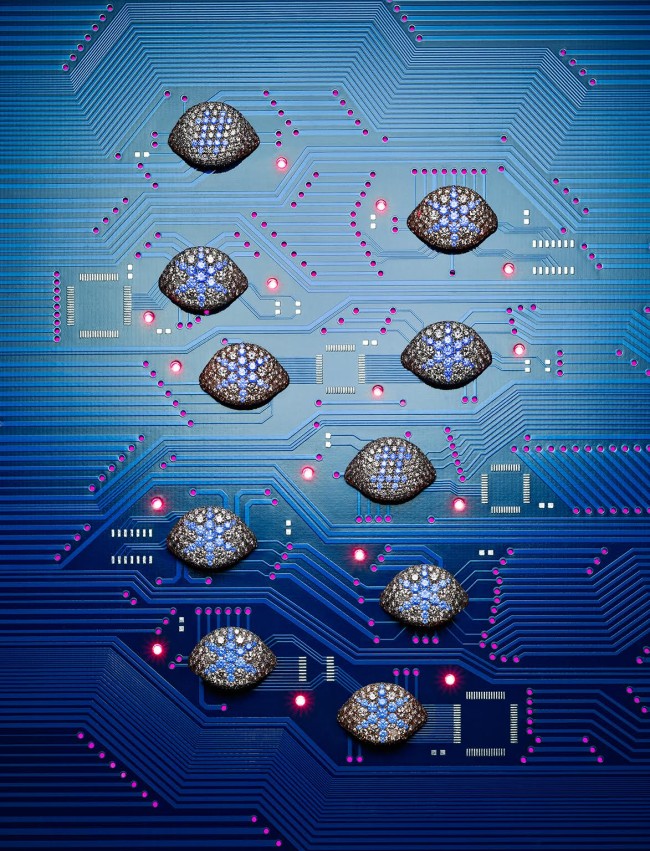

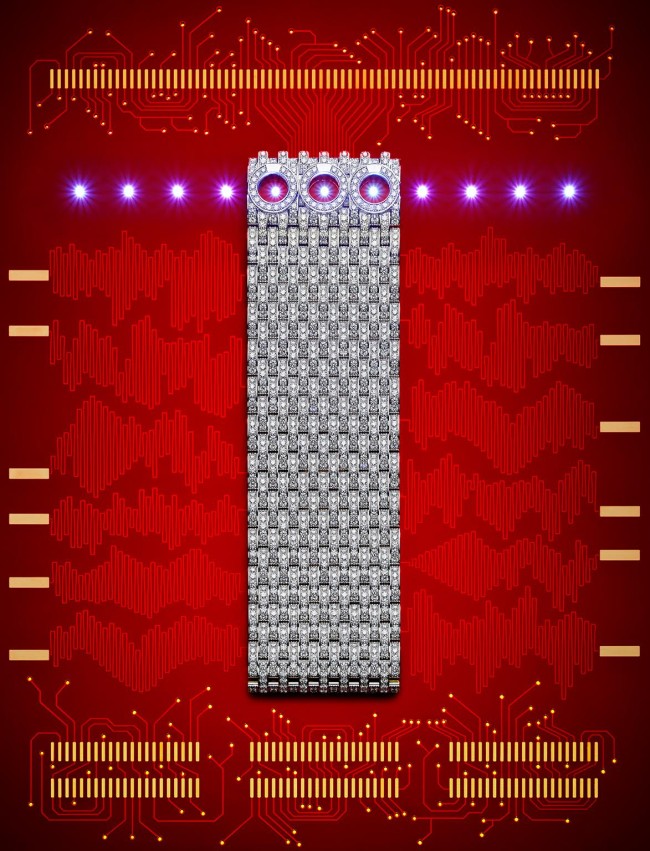

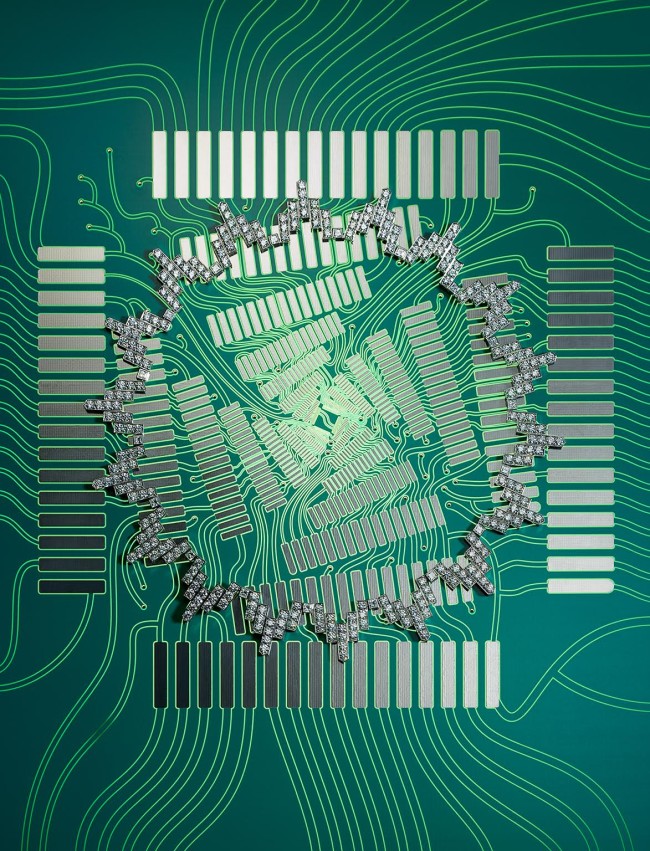

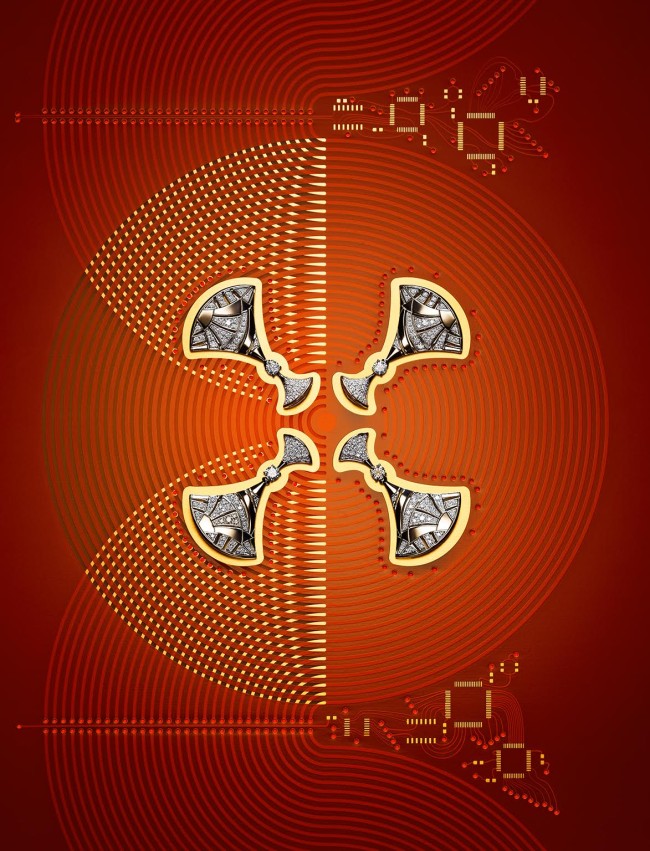

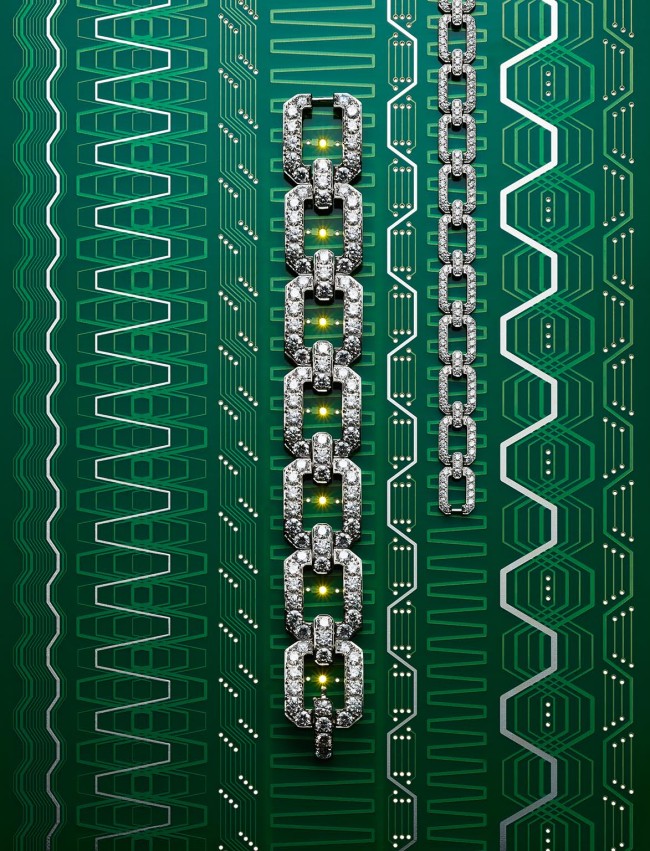

For the Haute Tech story, Kyle mentioned that he had a fine jewelry December story in search of an idea. Fine jewelry can be a tedious editorial subject because designs generally do not evolve much from year to year and diamonds are unforgiving in poor lighting conditions — a tough subject to make fresh.

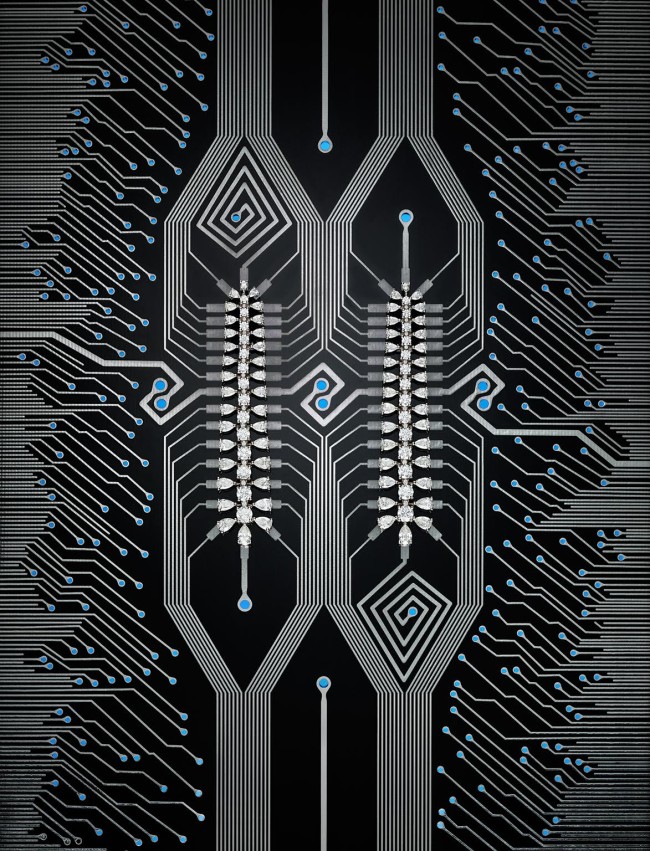

I have been involved with a couple of technology projects and developed an appreciation for a well-designed circuit board. Apple’s boards, in particular, are very fine, all black, with an absolute, maniacal fidelity to minimalism. I immediately thought of making boards that in some way reflected or enhanced the design direction of the jewelry. Kyle worked hard to find pieces that would mesh well with the concept — no animals or organic designs, for example.

How long did the project take and tell us about your process with the engineer?

The editors loved the idea and I got to work in July. We all figured no one had done this, at least not at this scale. My original intention was to design and order the prototype boards myself. I spent a day or so learning the nomenclature and general design principles. I already knew that board design can be devilishly difficult in the details, but straightforward designs are fairly easily to execute. There is a very large community of amateur board designers associated with platforms like Arduino, as well as many foundries that specialize in prototyping. I downloaded one of the popular free software packages and set to work. I started with a good drawing I had already made in Photoshop for the first design – the black Chopard board. Then I hit an unexpected wall. Circuit board software is designed to make circuit boards, not pretty patterns. Duh. A user first builds a schematic with all the components and only then moves on to “routing”, finding the shortest, most efficient paths to lay the “wires” between all the components. Clearly, I was not going to easily figure out how to build a schematic that would allow me to “route” the wires in a predetermined pattern.

Help was needed. I spent a considerable amount of time on tech blogs and the Web looking for an engineer that had both an aesthetic view on the world and the technical skills required. I came across one man, a fellow in England named Saar Drimer, who had a circuit board design company called Boldport. He had gone so far as to write a program that allowed him to import illustrator files into a circuit board-friendly design environment. I emailed him almost immediately. He quickly understood my project. I had found my guy.

I’d imagine the sketches were fairly in-depth in order to create the final “working boards,” tell us about that exchange.

We encountered many technical difficulties. I had to visit the jewelers and carefully measure the dimensions so that the jewelry would fit perfectly into the designs. This was very difficult to figure out, as cutouts also had to be drawn up for the rings and earrings. The magazine was extraordinarily helpful in opening doors, and we were lucky none of the pieces were sold before the shoot. Saar started with my drawings but soon added his own special sauce, making the boards more credible. By the end, we were going back and forth with very rough drawings and he took it from there. It was a lot of work for him, as he also had to design and solder functioning boards with the LEDs. I was also lucky he had a very good foundry in the UK that was willing to work hard on the quality and color of the shadow masks (the non-metallic surface of the boards). We spent about six weeks start to finish. The shoot took just two days, up in my Connecticut studio. There is almost no retouching, just a little cleaning up. I’m old school, I like my images real. We both feel that we executed something new, perhaps opening the door to new designs with circuit boards as a functional, aesthetic material.

How do your ideas manifest?

I wish I knew. they just pop in unexpectedly. On a long walk, in the shower, at an exhibition, anywhere, really. I read a lot, I look at design blogs, magazines, many non-photographic sources. Unless there is a specific request I stay away from my colleagues’ Websites; too many voices in a photographer’s head can be deafening.

What was your break, meaning how did you get started? Everyone has a breakthrough project though we all see you as superstar out of the womb.

Thank you. I do not know if I was a superstar out of the womb; I’ve been told that I produced a lot of spit up in my early years. Unless you are Guy Bourdin, many years of work will be required before you find a strong voice. That might be daunting to hear, but I think the best photographers love the process of making photographs. Your voice will come, sometime soon, hopefully. In the meantime, I suggest you make images simply for the joy of it. I have always felt that way, even during the years when my career was uncertain. As in all creative endeavors, this is a tough business. Do it because you love it. Still life photography has always felt like the best way to express myself, I have enjoyed a lifetime exploring how that happens.

What is another creative outlet for you?

Three years ago my wife and I moved to a small farm in Connecticut. I have learned a lot about fencing (not the epee kind), black bears (don’t run), and wild turkeys (not happy when challenged). More than enough new outlets for a guy who spent 28 years in Paris.

3 Comments

These shots are spectacular. I love the concept and execution.

Thank-you for nourishing the creative brainwaves … it’s not often that I get stopped in my tracks with some truly original imaging, but this did it for me!

I have so much love for this shoot. Well done Mitch.

Comments are closed for this article!