By Bryan Sheffield, Wonderful Machine

Concept: Stylized Still Life photography and videography, as well as images of the product being used.

Licensing: 2 years of E-Commerce and Web Collateral of all content captured.

Photographer: Product specialist.

Agency: Medium-sized US-based agency.

Client: Specialized hair care product manufacturing client.

Summary

I recently helped a Photographer/Director build an estimate, along with navigating and negotiating a project with a marketing/advertising agency seeking stills and video for a campaign they were creating for their specialized hair care product client.

The creative brief from the agency described the still-life content of a new product. They wanted the images/video to feature the product being used on set. The idea for the settings consisted of colorful and minimalistic bathroom and bedroom mirrors. The content needed to feature talent applying the product to their hair. The final use of the content was described as web and social placements, as well as “eComm” use on the client’s and select retailer’s websites.

Our creative calls with the agency left us feeling like this project was not yet greenlit by the client. This was because they had so few details to share. Instead of quoting on an actual project, it seemed as though the agency was asking us for a quote which they would then present to their client as they were proposing the work to be created.

I was clear with the photographer that I have seen cases like this become a game of revisions and sometimes “how low can we get the costs while still maintaining the creative needs.” The Photographer/Director was on board and we put our heads together to formulate a production plan. It included 1 pre-light day, 2 shoot days, the needed crew, and production support. We submitted our 1st estimate based on the initial ask.

Fees

Based on the client, agency creative description, and shot list of 6 setups we intended to use, I felt that $14,000 would be in the mid-to-high range of what the client might be expecting to see. Depending on the brand, I have seen similar use license projects range between $4,000 and $14,000/day for all content captured. Because this shoot was for a single, limited audience product, $7,000/day was appropriate here, given the market and the client’s desire to work with this particular Photographer/Director. I added 4 pre-pro days at $1,000 each for the Director/Photographer for client and crew creative meetings, creative planning, as well as a pre-light day.

Crew

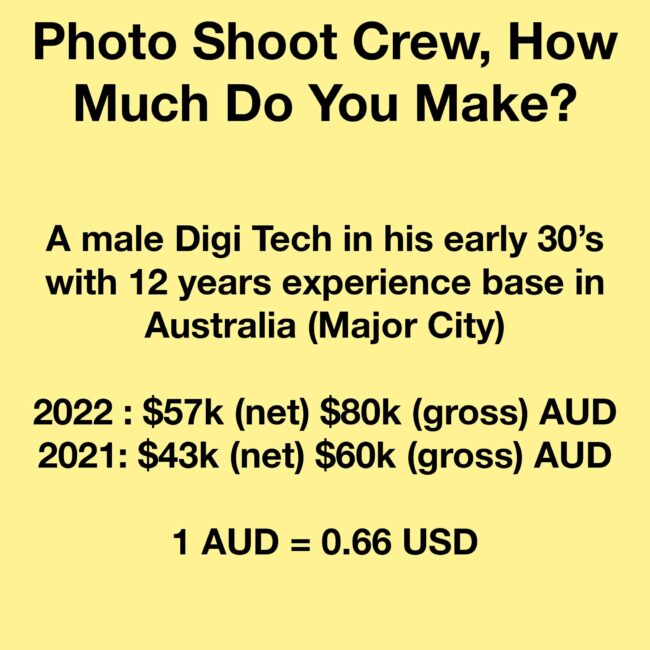

We added a DP/Camera Op at $2,000/day to run video capture while the photography was happening. We added 2 pre-pro days for the DP/Camera Op at $750/day. First and Second Assistants were included to help with lighting and camera equipment management. They would be needed on the pre-light day as well. We added a Digital Tech/Media Manager at $800/day to manage and display the content as it was being created. We added a Producer at $1,000/day, and a Production Assistant at $350/day. These fees were consistent with previous rates the Director/Photographer had paid their team on past productions in this city.

Equipment

We included $5,200 for cameras, lighting, and grip rentals. The Director/Photographer would bring their own still and video cameras, lenses, and lighting. They also intended to rent some supplemental continuous lighting, c-stands, and sandbags from a local rental house. $750/day was added for the Digital Tech’s workstation rental. We also included $850 for 3 large hard drives and $1,800 for TBD needed production supplies. This included production book printing, table/chair rental, heaters, wardrobe steamers, racks, etc.

Casting & Talent

We added usage fees and 2 daily session fees for two talent. Based on the limited info, but our assumed talent specs, we felt confident in a rate of $2,200 plus a 20% agency fee. We added $2,000 as a fee to cast the two talent. We also added 23% for talent payroll needs within the bottom line.

Styling Crew

We added a combo Hair/Makeup Stylist at $950/day. For our anticipated wardrobe styling needs we added a Wardrobe Stylist at $1,100/day, and an assistant for $500/day. We added $1,600 for the assumed 2 unique outfits per talent and marked this as TBD pending final creative direction. We added a Nail Stylist for both shoot days at $1,200/day. Based on our understanding of the set design and prop needs, we added a Prop Stylist at $1,200/day, as well as an assistant at $500/day. Props & Materials was estimated at $8,500 and marked with a TBD pending final creative needs.

Location/Studio

We included 3 days at a rented studio at $1,800/day.

Meals

We included $70/day per person for meals and craft services. Additionally, we added $500 for meals/craft services on the pre-light day.

Misc.

We included $1,800 for insurance and $1,600 for additional meals, expendables, and miscellaneous expenses.

Post Production

We added $750 for the Director/Photographer to perform a First Edit for Client Review and costs for retouching an estimated 30 images at $125/hour.

Providing a Second Estimate

The client stated that the estimate and treatment were received and that they would like to see a 2nd estimate without production support and with the agency handling all talent and styling. We submitted a revised estimate the same day and then heard that they would circle back after reviewing it with their client. This estimating process then became quite involved as the agency team presented the project to the client and came back to us multiple times for revisions. Together we ended up creating 8 estimates for the project over 6 weeks. While a client requesting multiple estimate revisions is not unique, what made this process arduous was each new estimate requested was to be based on revised shot lists or agency-suggested ways to slim the bottom line. Our requests for budget parameters were never answered.

An Overview of Estimates

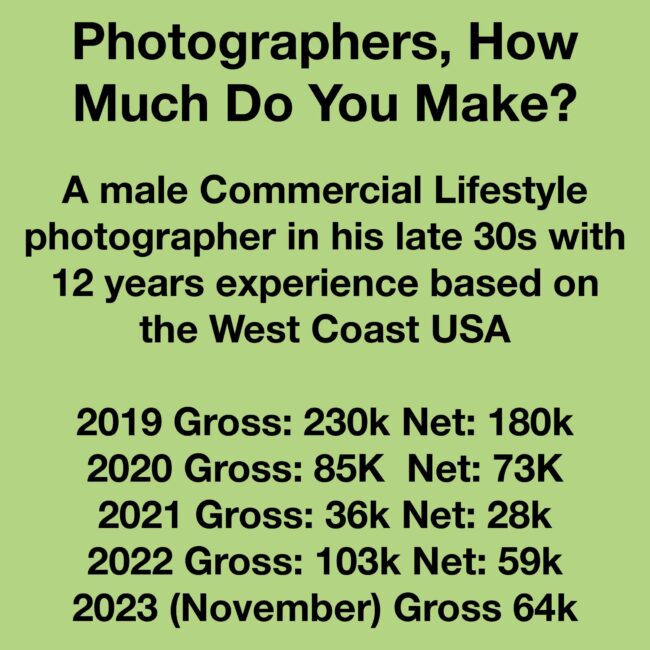

While it would be quite complicated to include each of the multiple estimates within this article, below is a high-level overview of each to demonstrate the project scope and cost changes:

1st estimate above.

2nd estimate — Client requested: No production support, talent and all styling would be handled by the agency. Our estimate was the above with the noted items removed and came out to $50,550.

Five weeks later, a 3rd estimate was requested — Client requested: All production, 2 talent over 2 shoot days, all styling, adjusted shot list with retouching for 26 images. Our estimate was $111,870.00.

One day after the 3rd estimate, we were asked for a 4th estimate — Client requested: All included within 3rdestimate, but no DP, no producer, the agency handling all art & props. This estimate was $75,270.

Two days later, 2 additional estimates were requested:

5th estimate — Client requested: A 1-day shoot with no talent, no DP, no producer, agency handling art & props, a VERY revised shot list, and only 3 final images retouched. This estimate was $20,640.

6th estimate — Client requested: A 2-day shoot with 2 talent on only 1 day, no DP, no producer, agency handling art & props, 12 images retouched. This estimate was $56,750.

The 7th estimate request came three days later — Client requested: Increased shot list, 2 unidentifiable hand model talent, 1 pre-light, 2-day shoot, no DP, no producer, agency handling all art & props, and 30 images retouched. This estimate was $66,450.

The Final Estimate

The 8th estimate (final) was sent the following day — Another revised shot list, 2 unidentifiable hand model talent, 1 pre-light day, 1-day shoot, no DP, no producer, agency handling all hair/makeup/props styling, and any video editing, 4 images retouched. In this instance, the agency did let us know that the project needed to be completed by a specific date that was about 2 weeks out. I let the agency know that to hit that date we would need approval and advance payment within 3 days and in order to expedite the process I requested a budget (again).

The agency let me know that they had $40k approved. We submitted an estimate of $40,658.40. While our estimate was a little above the agency-stated budget, our gut told us they would approve the costs since the estimate contained exactly what they requested and the pressure of a short window until the work was needed in hand.

Fees

Based on the work to be created and the noted project budget, $8,500 was an appropriate fee. I added 5 pre-pro days at $1,000 each for the Director/Photographer. This was not only to manage client and crew creative meetings and planning but to source and book all crew and studio needs, as well as their pre-light day fee.

Crew

We included First and Second Assistants for the pre-light days and a Digital Tech/Media Manager at $800/day. We added a Production Assistant at $350/day to help the Director/Photographer with bookings, equipment prep, shoot day catering/craft services, trash, and logistics.

Equipment

We included $3,100 for cameras, lighting, and grip rentals. The Director/Photographer would bring their own still and video cameras, lenses, and lighting. They also intended to rent some supplemental continuous lighting, stands, and sandbags from a local rental house. Moreover, $750/day was added for the Digital Tech’s workstation rental. Additionally, we included $850 for 3 large hard drives and $800 for TBD needed production supplies such as production book printing, table/chair rental, heaters, wardrobe steamers, racks, etc.

Casting & Talent

We added usage fees at $1,200 and $500 1-day session fees. Plus 20% agency fees for 2 non-recognizable hand model talent. Additionally, $1,500 was set as a fee to cast the two talent. The Director/Photographer and Production Assistant would do the casting. We added talent payroll fees within the bottom line at 23% of the total talent fees.

Styling Crew

The agency/client was to provide all hair/makeup/wardrobe styling. However, it was requested that we source and hire a Prop Assistant to aid them. So we quoted this at $500/day. We included $250 per talent as a stipend to get manicures prior to the shoot. Because there were so many estimates created, we made sure to clearly note the Styling Crew lines as “Agency Provided.”

Location/Studio

We included 2 days at a rented studio at $3,600/day and noted that this would include the anticipated cyclorama painting and cleaning fees.

Meals

We included $70/day per person for meals and craft services, as well as $200 for meals/craft services on the pre-light day. Moreover, our client/agency headcount increased by 1 person as well.

Misc.

We included $1,100 for insurance and $1,200 for additional meals, expendables, and miscellaneous expenses.

Post Production

We added $500 for the Director/Photographer to perform a First Edit for Client Review and costs for retouching up to 4 images at $125/hour.

Results

The Photographer/Director was awarded the project and the shoot was a success! The client was on set and loved the work being created. As we all can imagine, the on-set creative requests from the client kept coming on the shoot day. The Photographer/Director called me during the shoot and mentioned that, due to the client’s additional requests (and delays), they were anticipating 2 hours of overtime for the crew and studio. I worked to get these costs approved by the agency during the shoot and we included the overages in the balance invoice. After reviewing the content, the client loved the work and contracted the photographer to retouch an additional 21 images for $3,150 (1 hour per image x $150/hr).

Expanding & Extending Usage

About 2 weeks after final image delivery the agency reached out for costs to expand the 2-year use of the content. They requested usage for in-store POP and web/print advertising purposes (we called this Unlimited use excluding Broadcast), as well as cost estimates for both extending the previous eComm and Web Collateral use and the new request of Unlimited use excluding Broadcast in perpetuity. These new uses would entail new fees and agreements with our 2 talent. We negotiated fees with the talent agents and submitted the below cost estimates to the agency:

eComm and Web Collateral use in perpetuity. Additional fees:

$8,500 licensing fee

$2,880 Talent 1 use fee ($2,400 +20%)

$2,880 Talent 2 use fee ($2,400 +20%)

Unlimited use in perpetuity. Additional fees:

$14,000 licensing fee

$5,760 Talent 1 use fee ($4,800 +20%)

$5,760 Talent 2 use fee ($4,800 +20%)

Note

In our experience, it is tough to get talent agencies to agree to perpetual use. Especially for Unlimited perpetual use without a very high rate. Agencies do this to protect their clients from a company using their likeness years in the future when that client might be very recognizable if they become the next Cameron Diaz etc. Agents also limit the use duration often. This occurs for fear that their clients might not get booked for projects with competitor brands. In this case, neither of those scenarios was a factor since the talent was hand/hair models without recognizable faces.

With my advice, the Director/Photographer agreed to present a lower Unlimited use rate for themselves with the goal of selling that through to the client over the limited use in perpetuity. As of the writing of this article we have yet to hear back from the client/agency on their decision to expand or extend the use.

Follow our Consultants @wonderful_at_work.