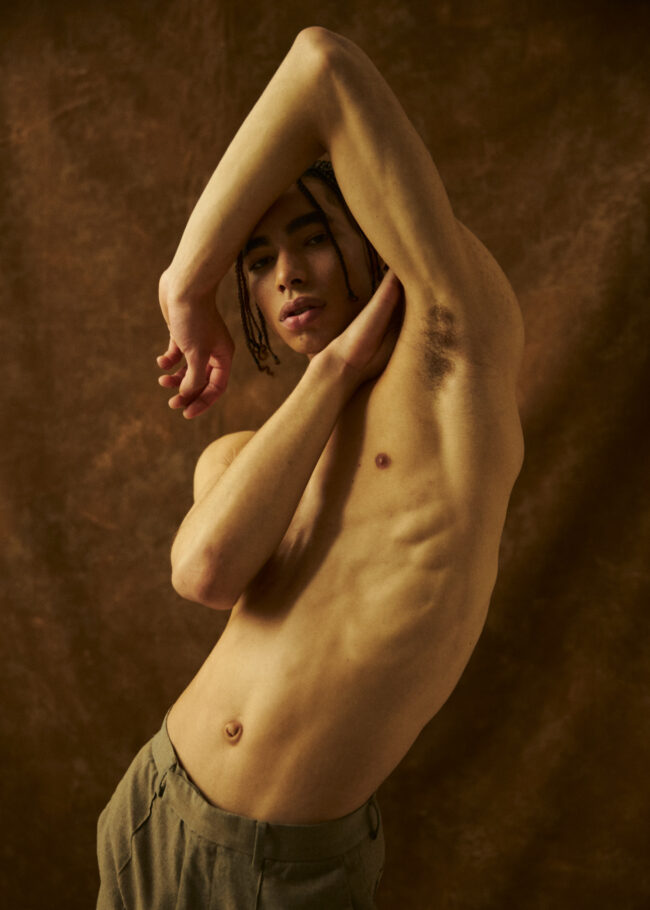

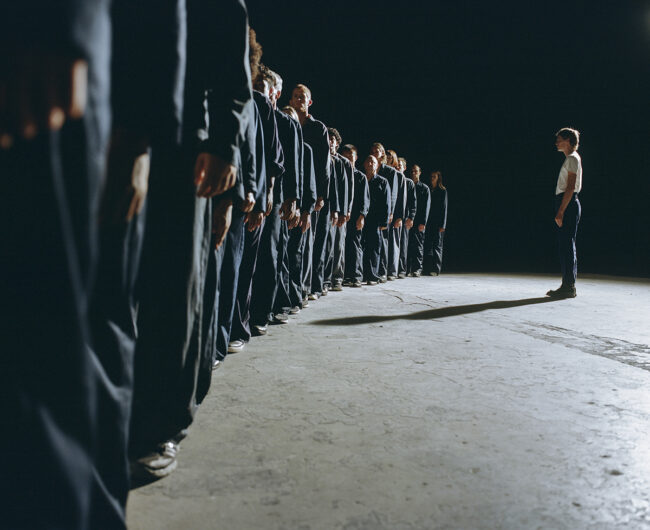

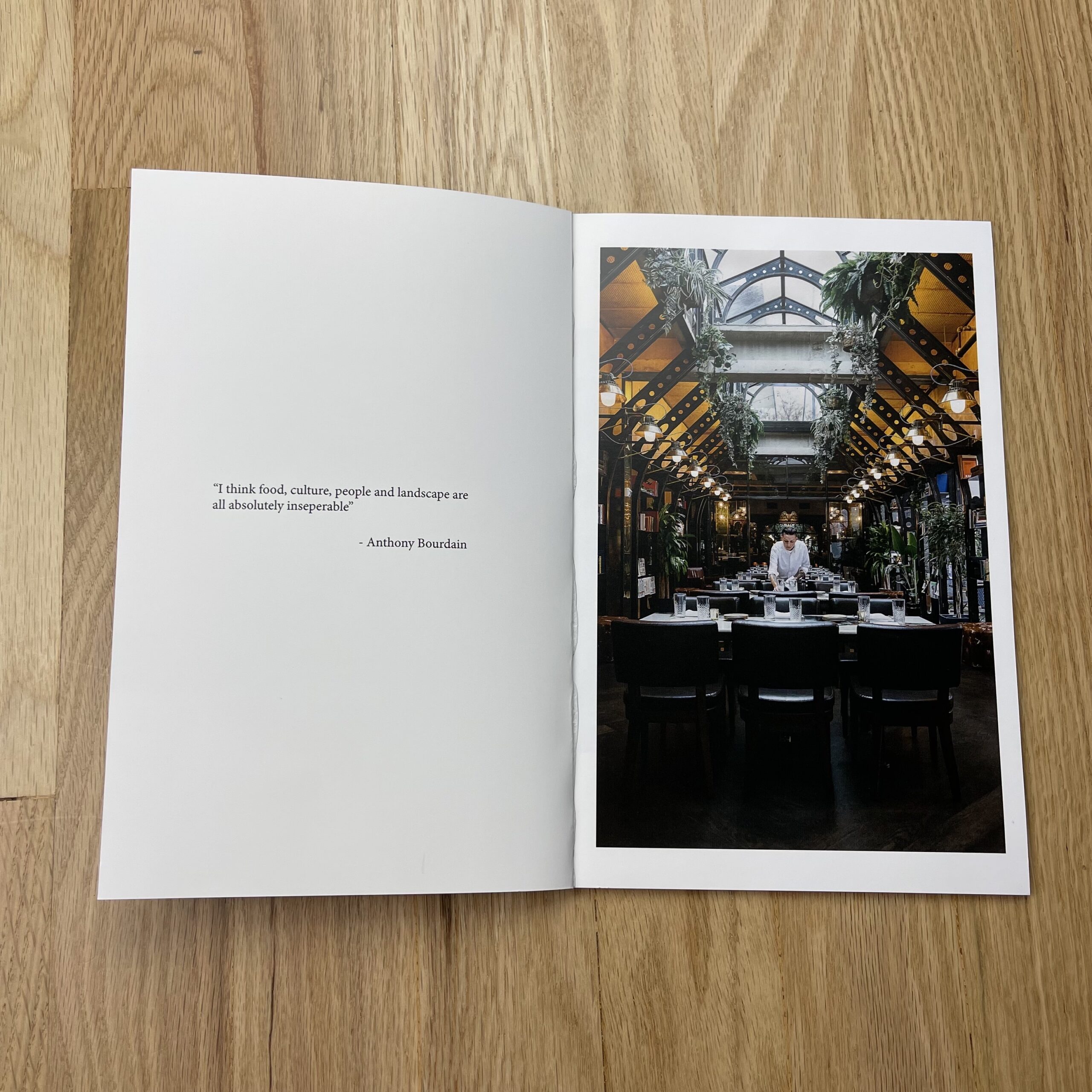

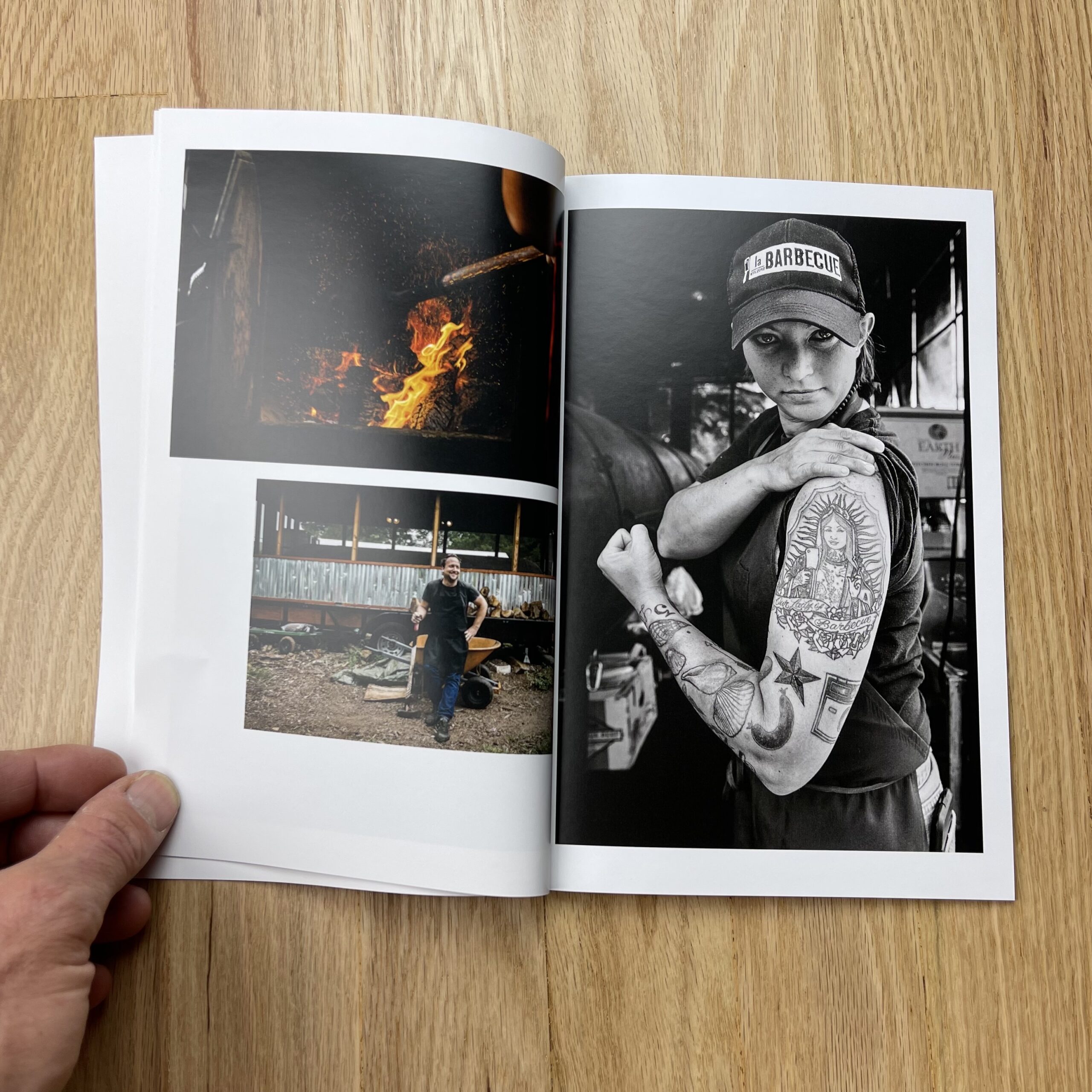

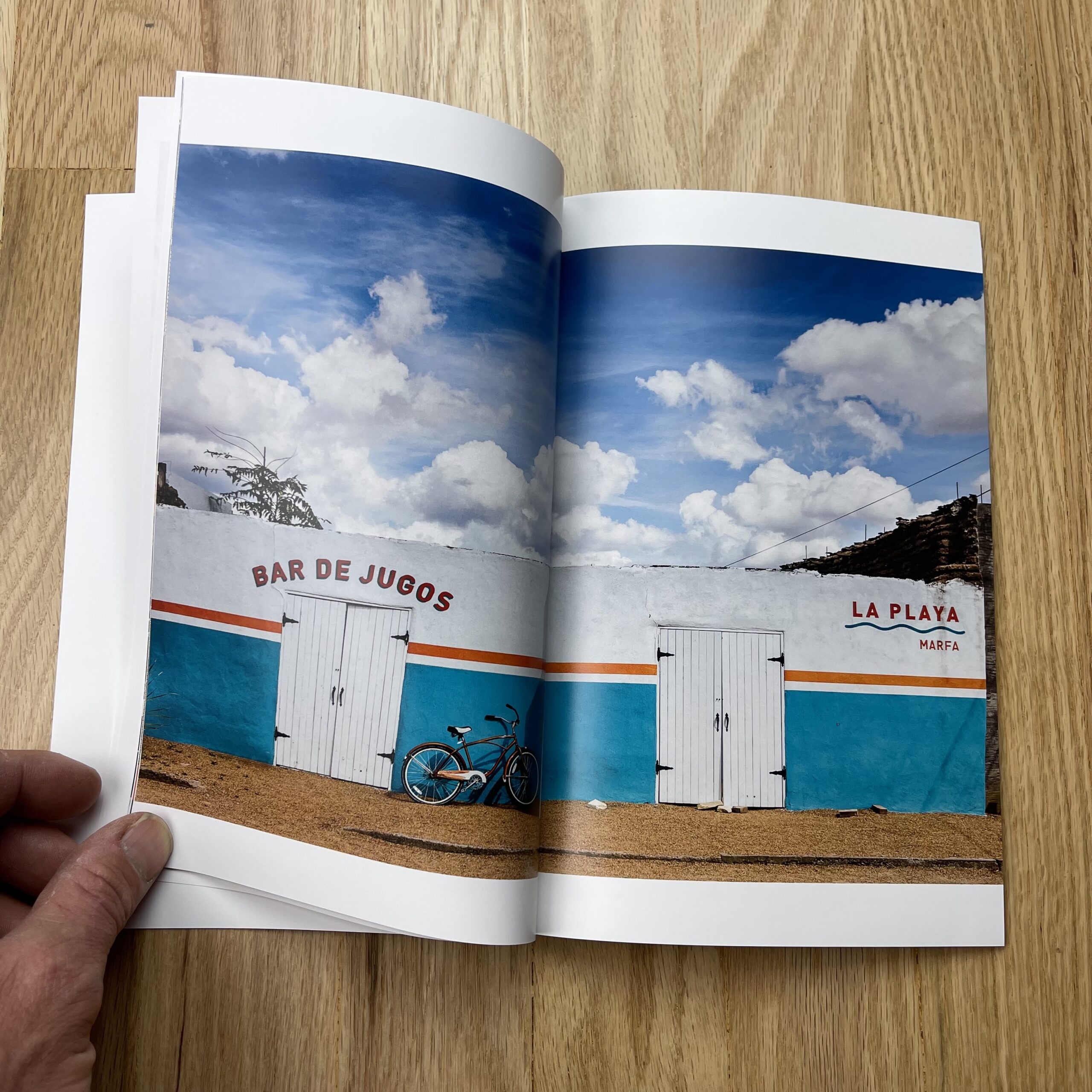

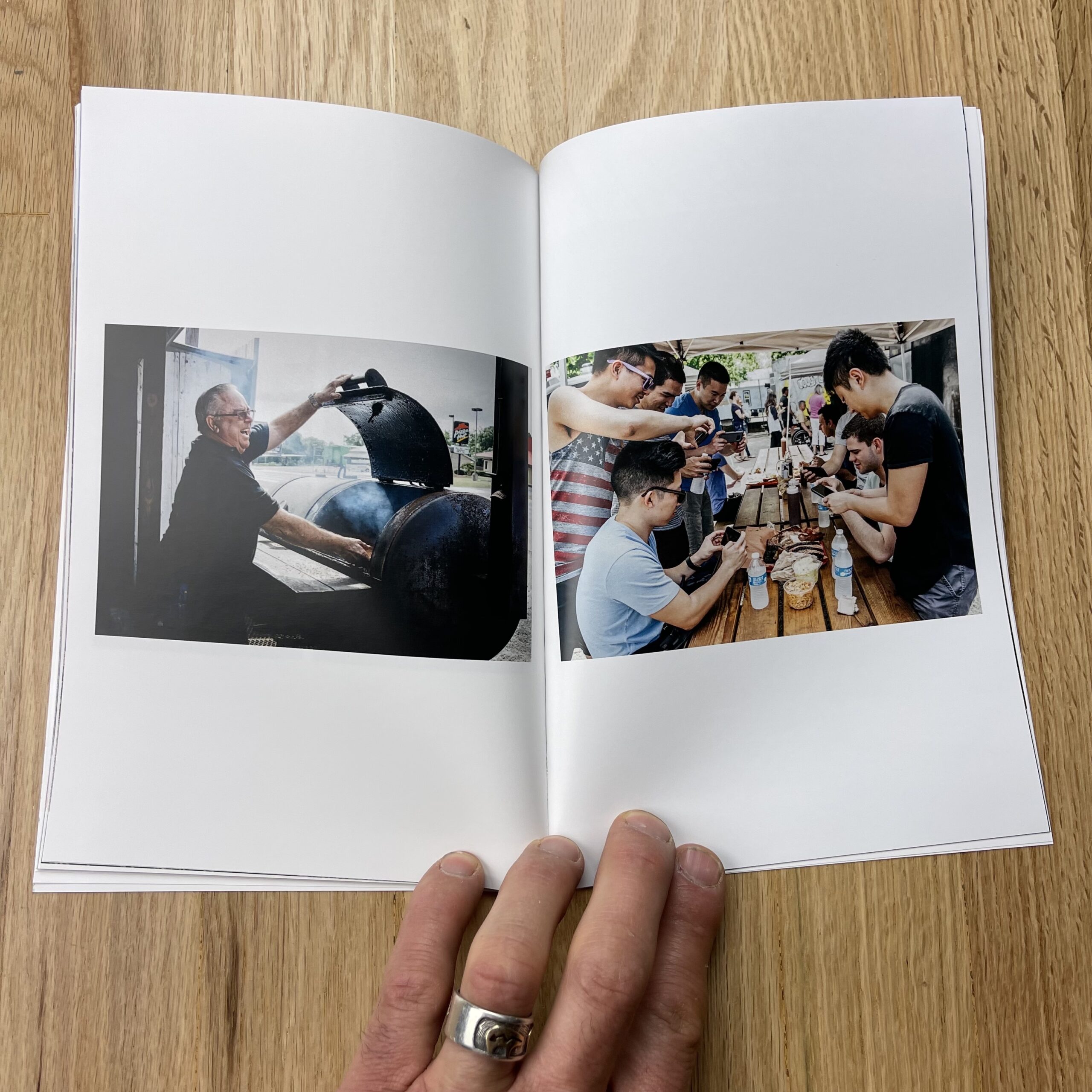

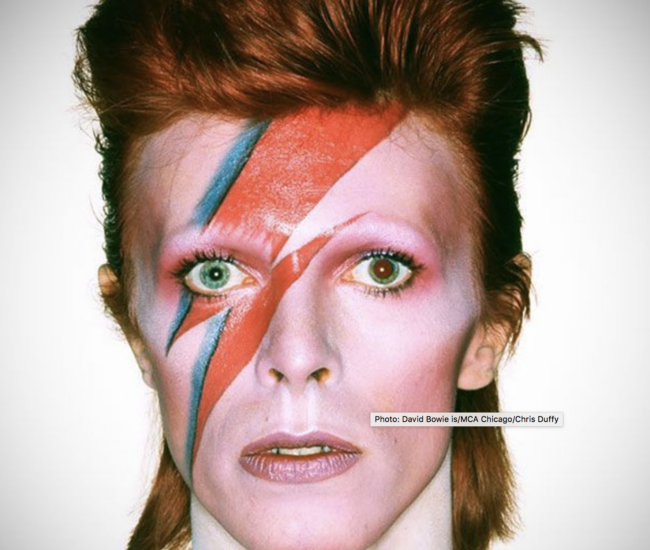

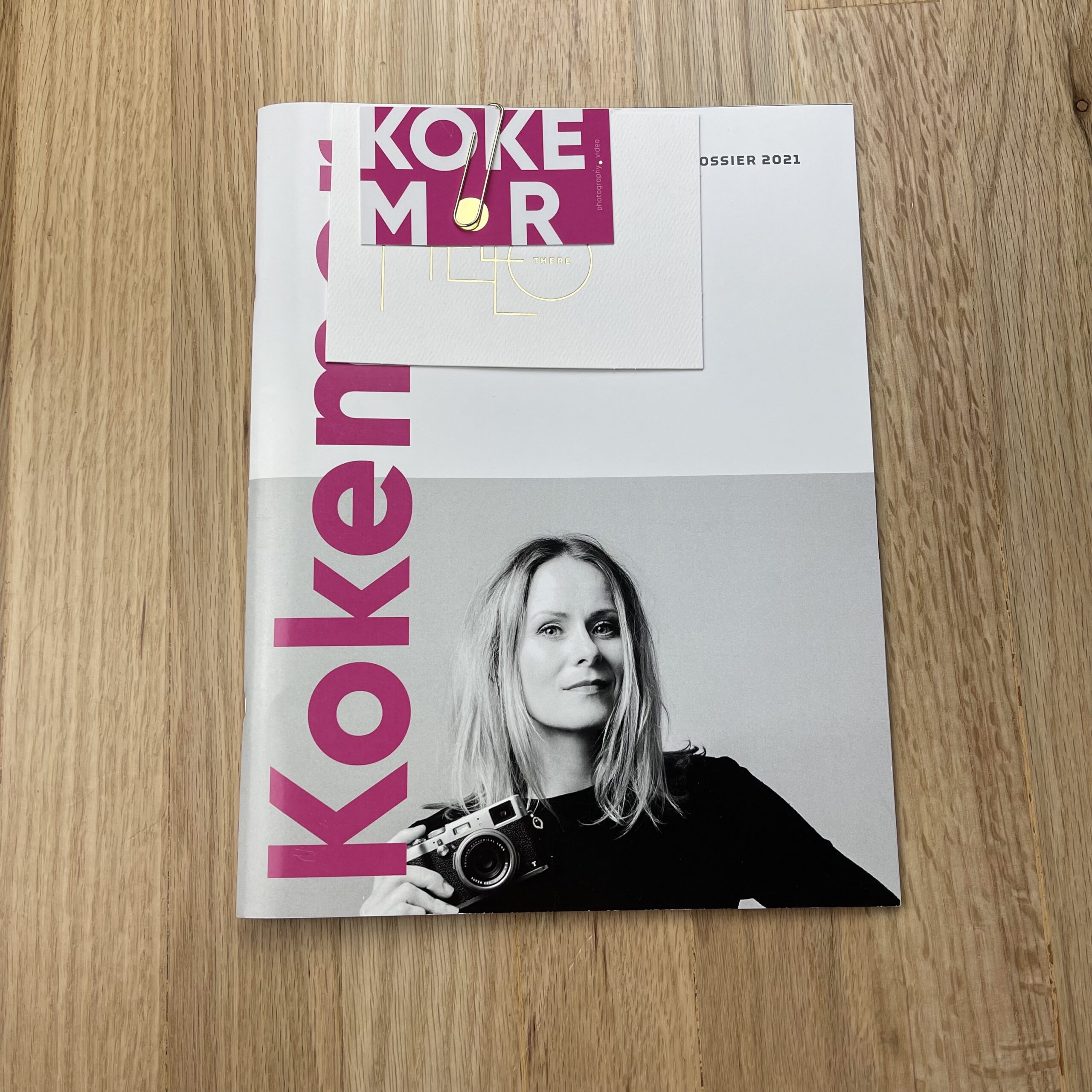

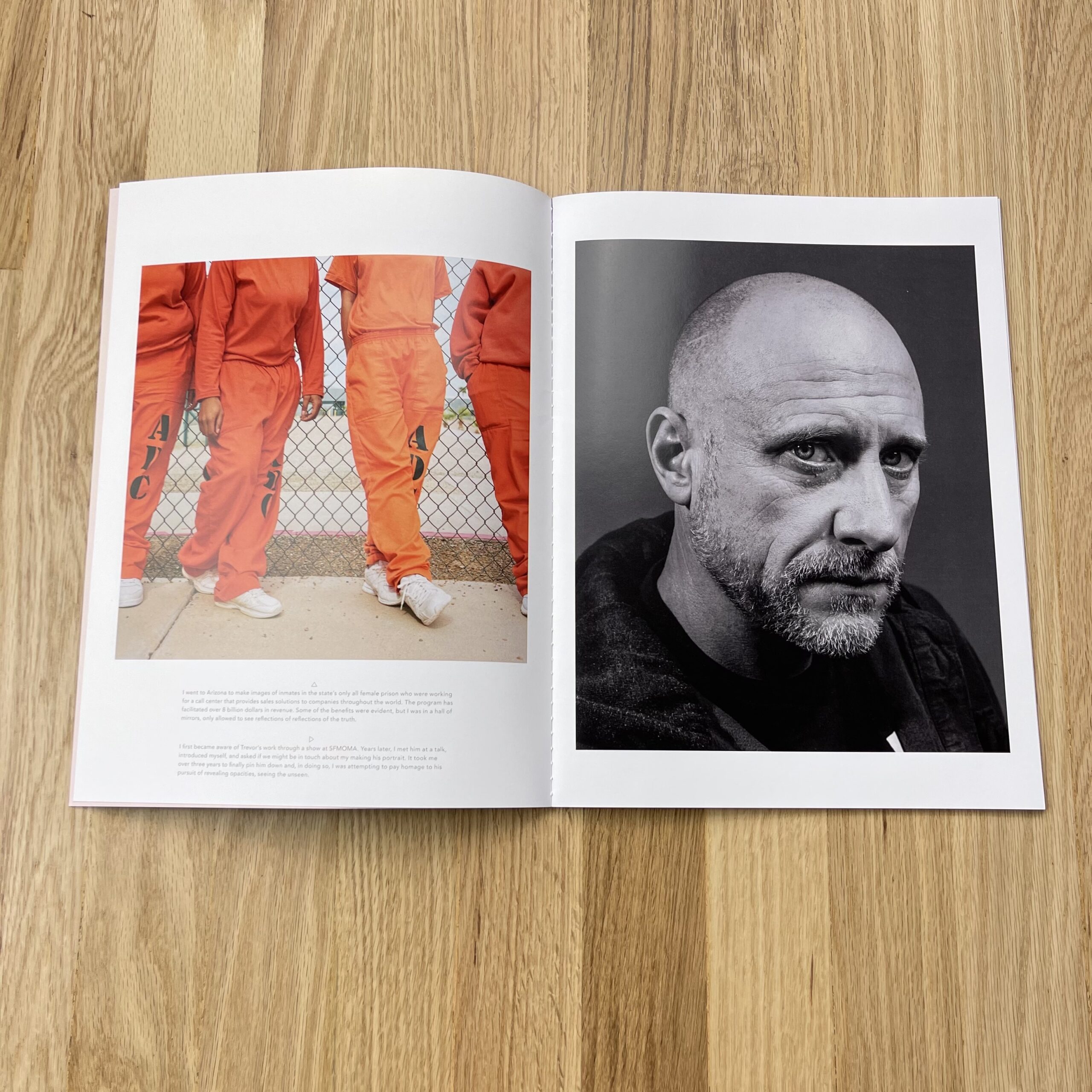

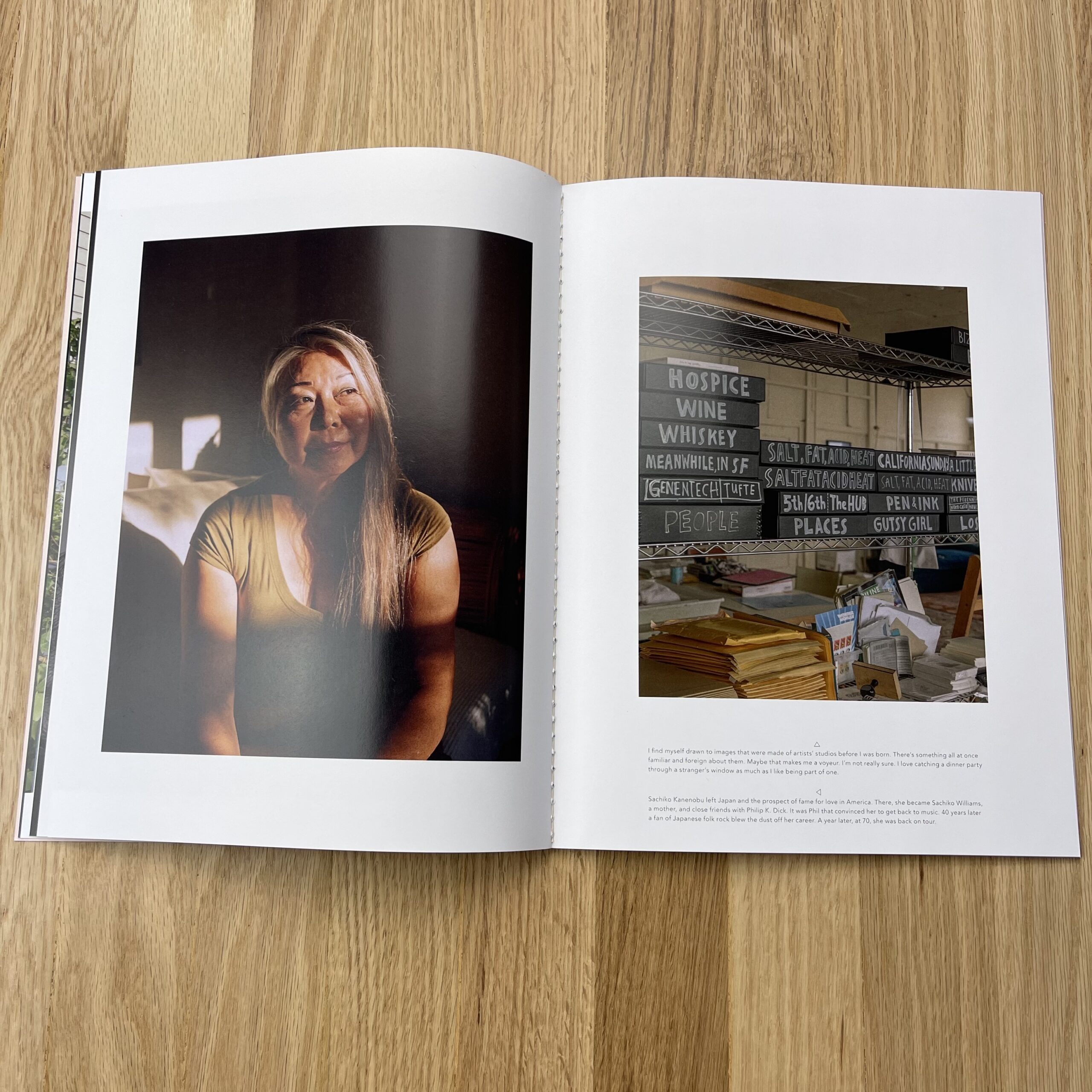

Photograph by Gladys Lou (2021)

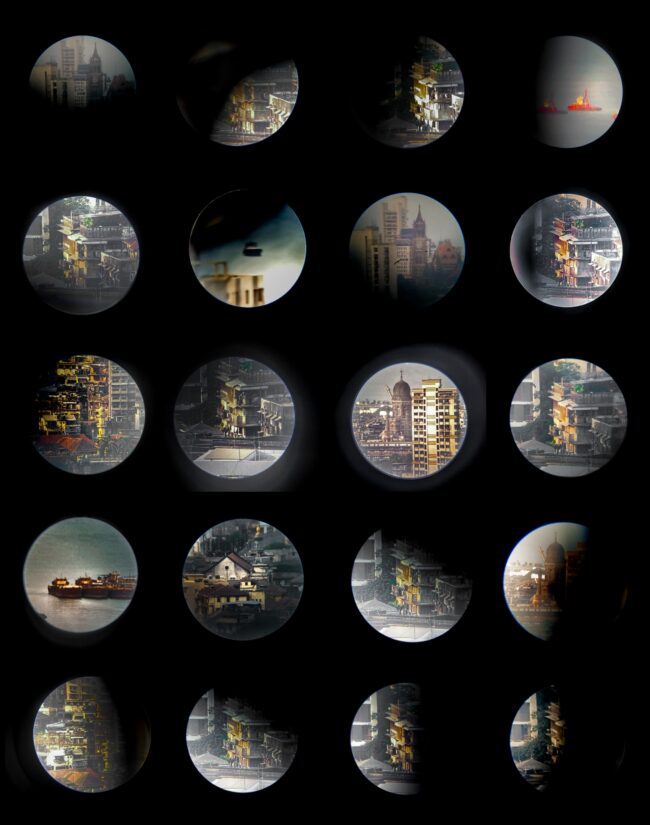

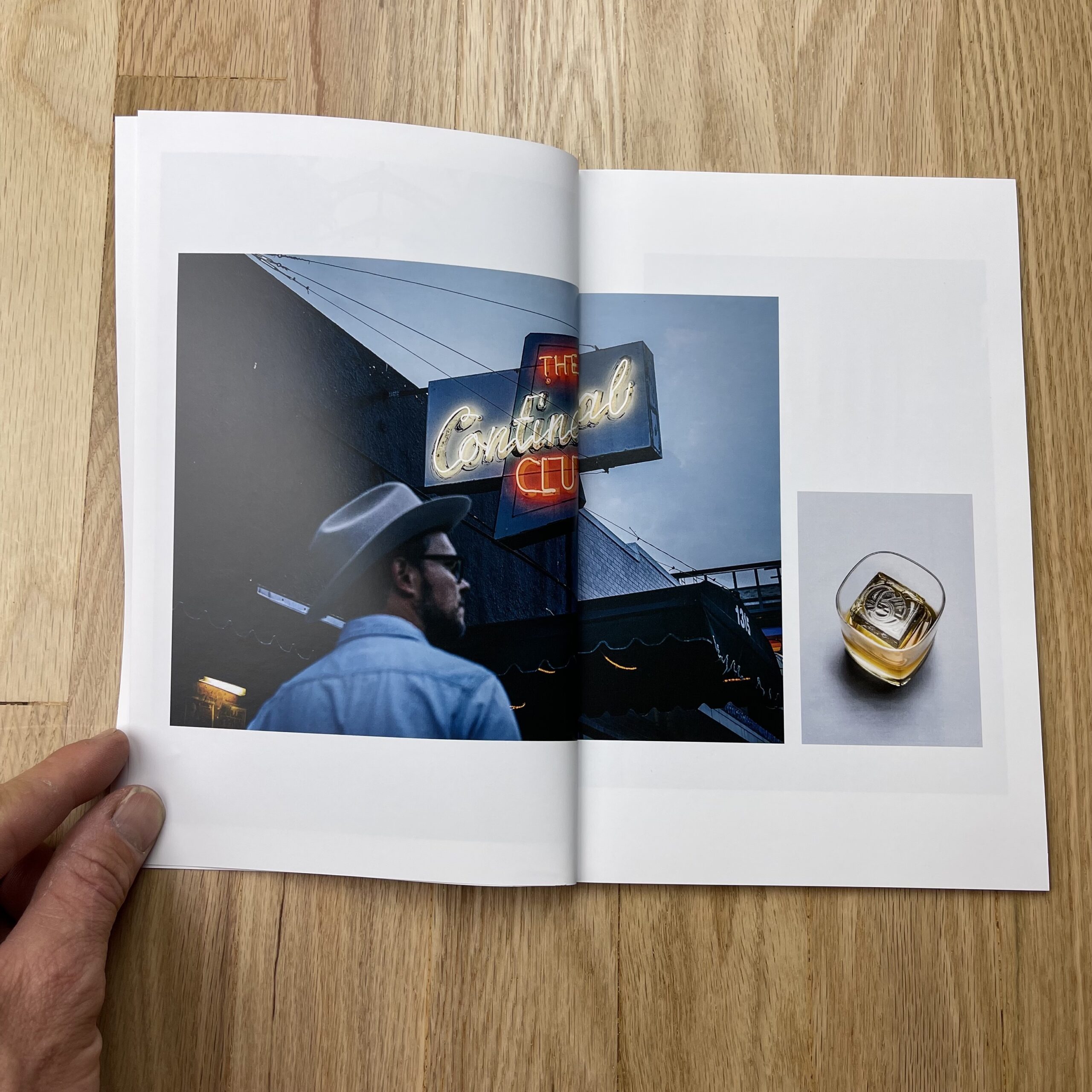

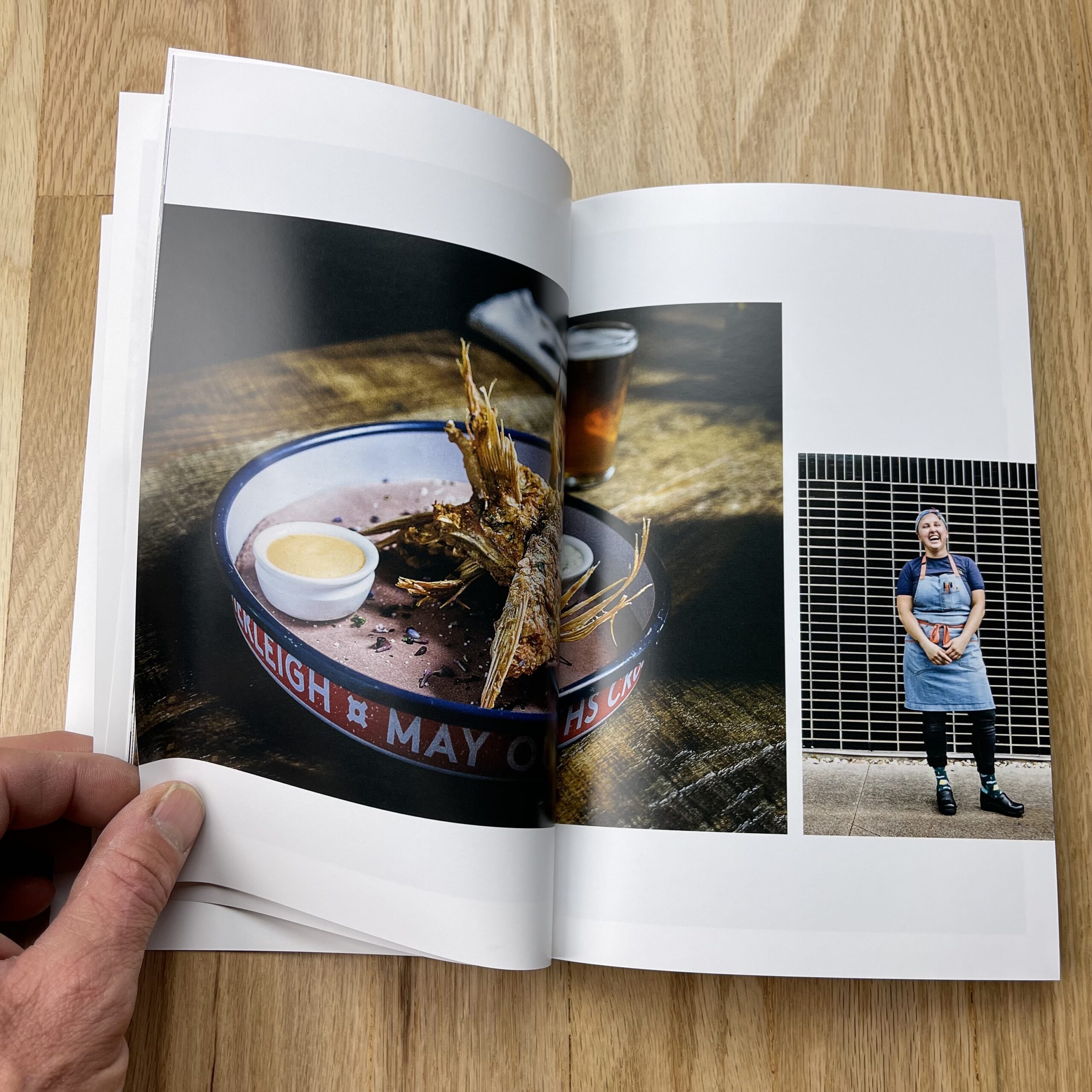

Photograph by Gladys Lou (2021)

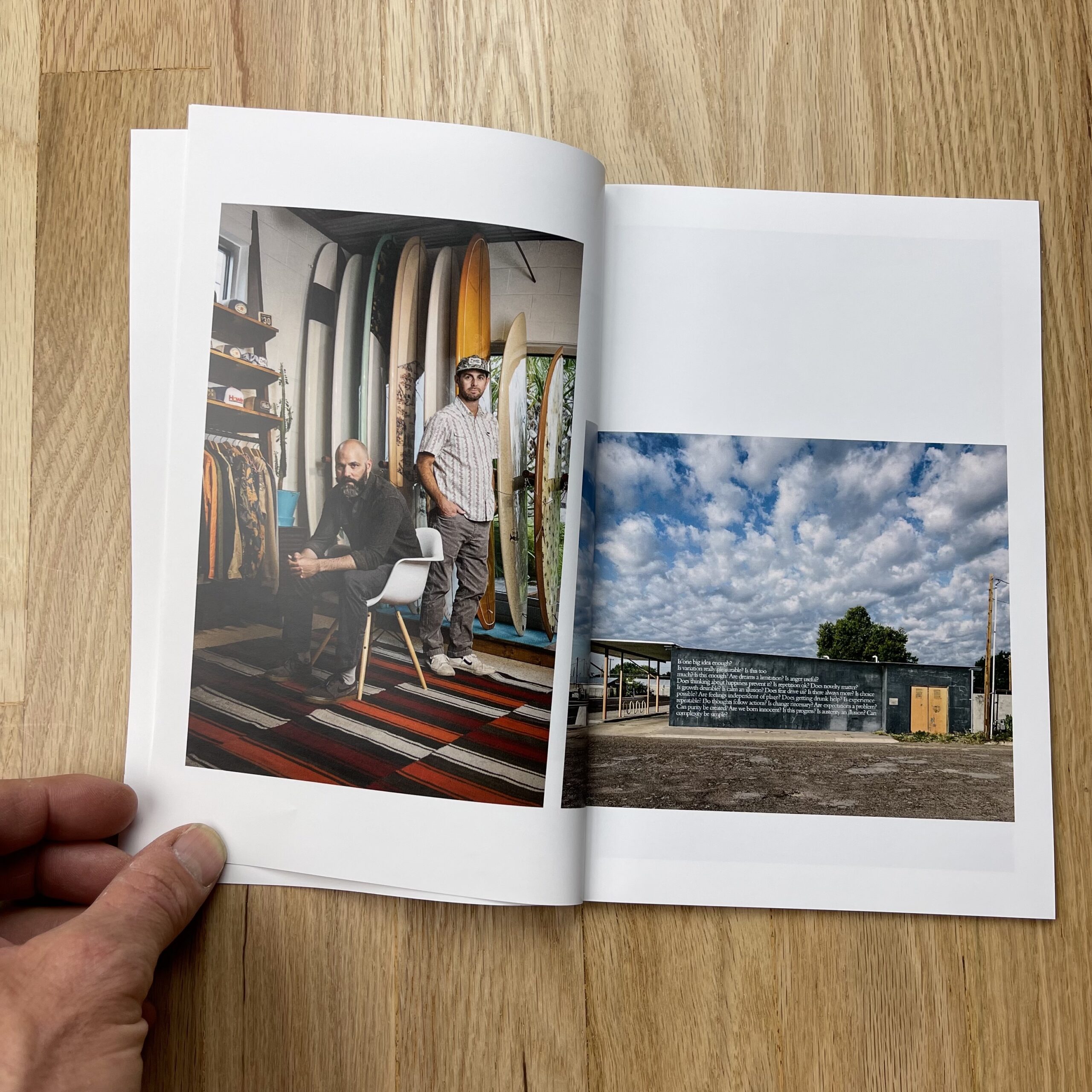

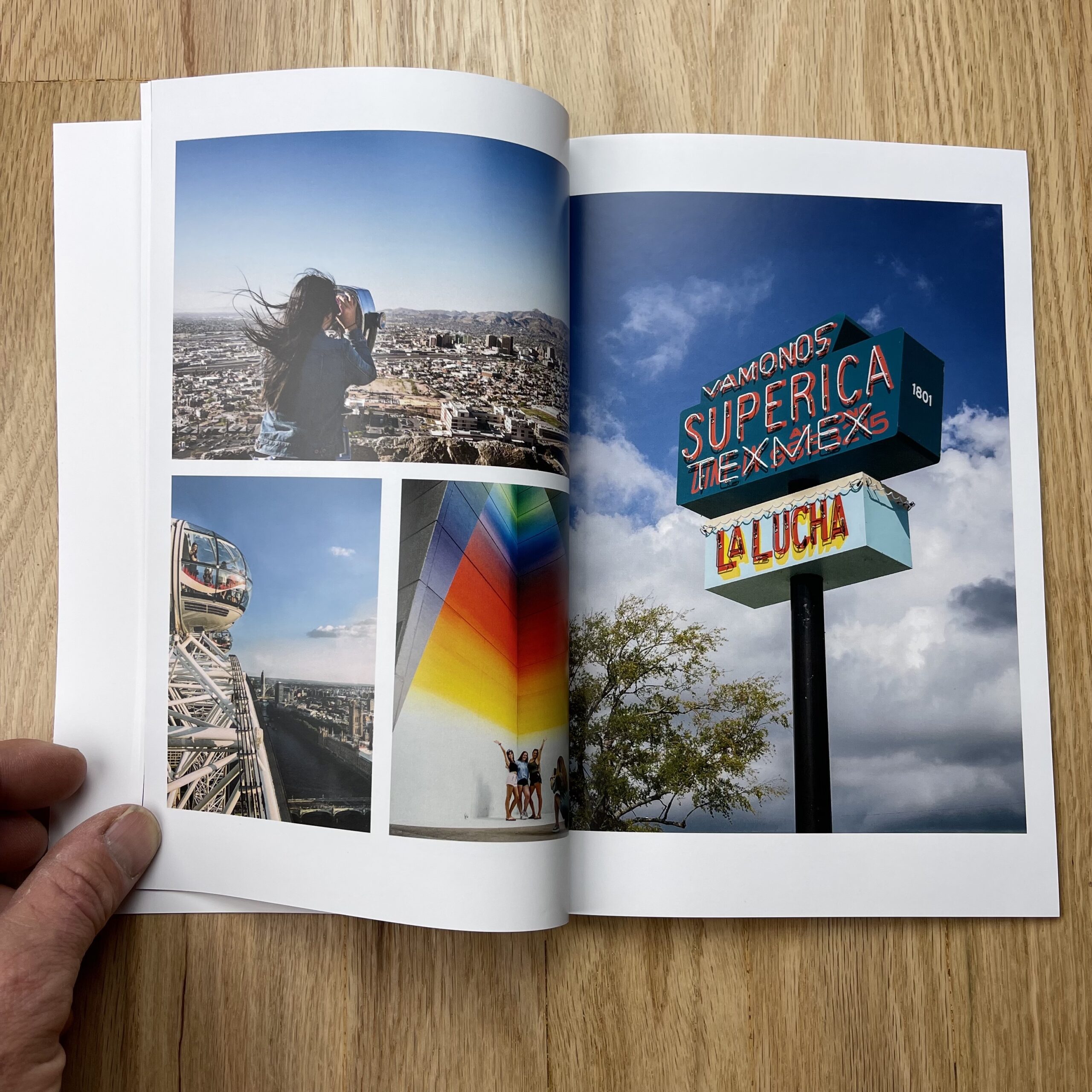

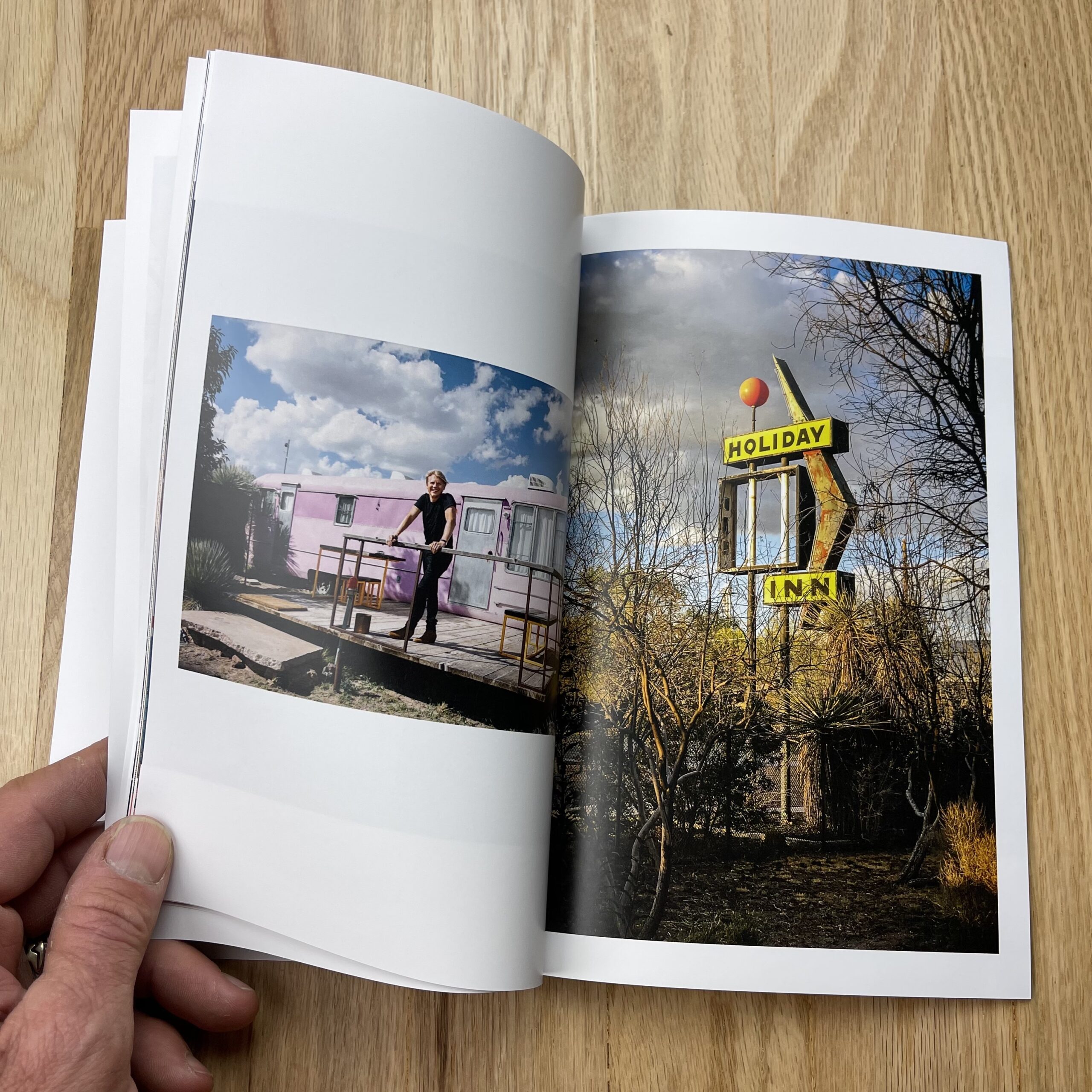

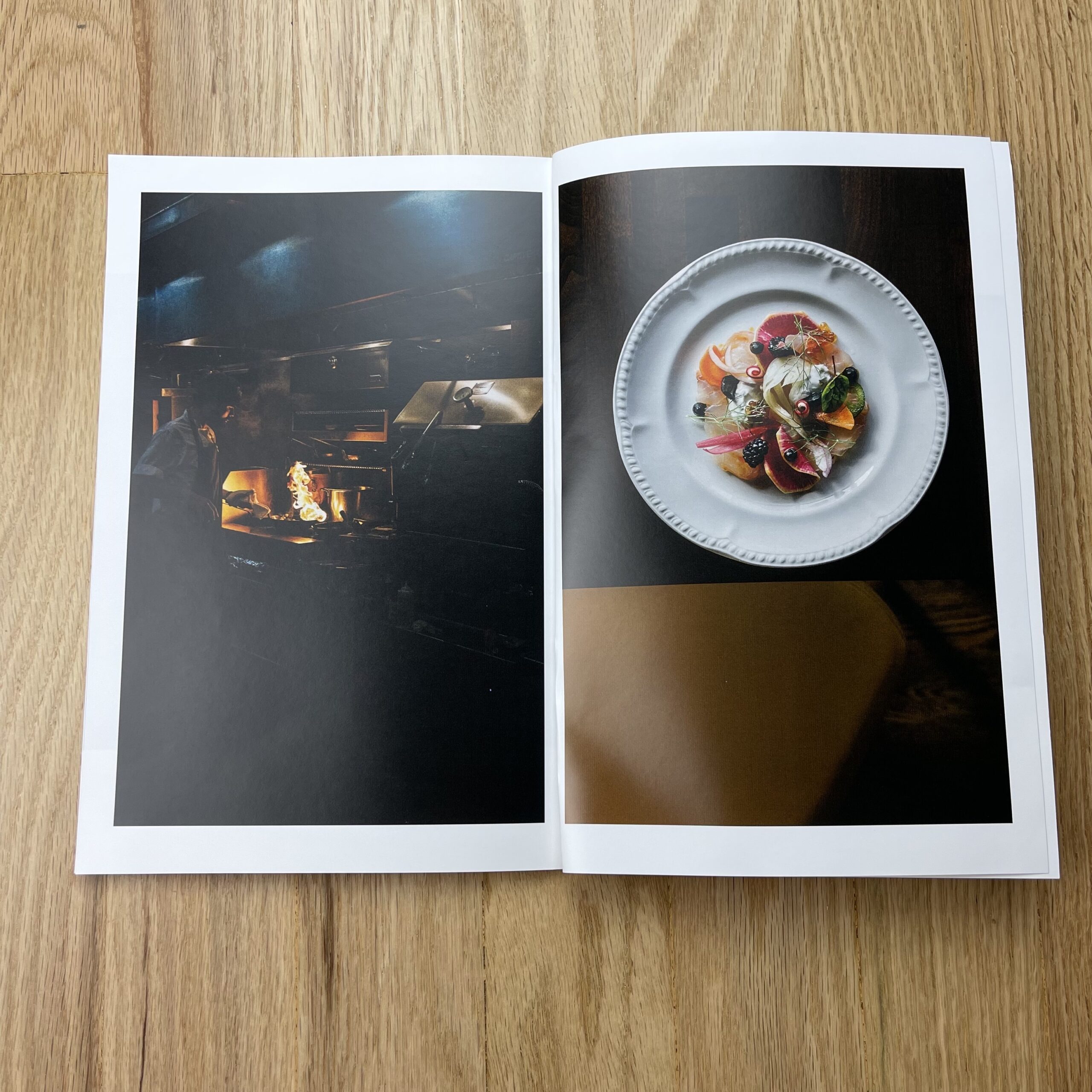

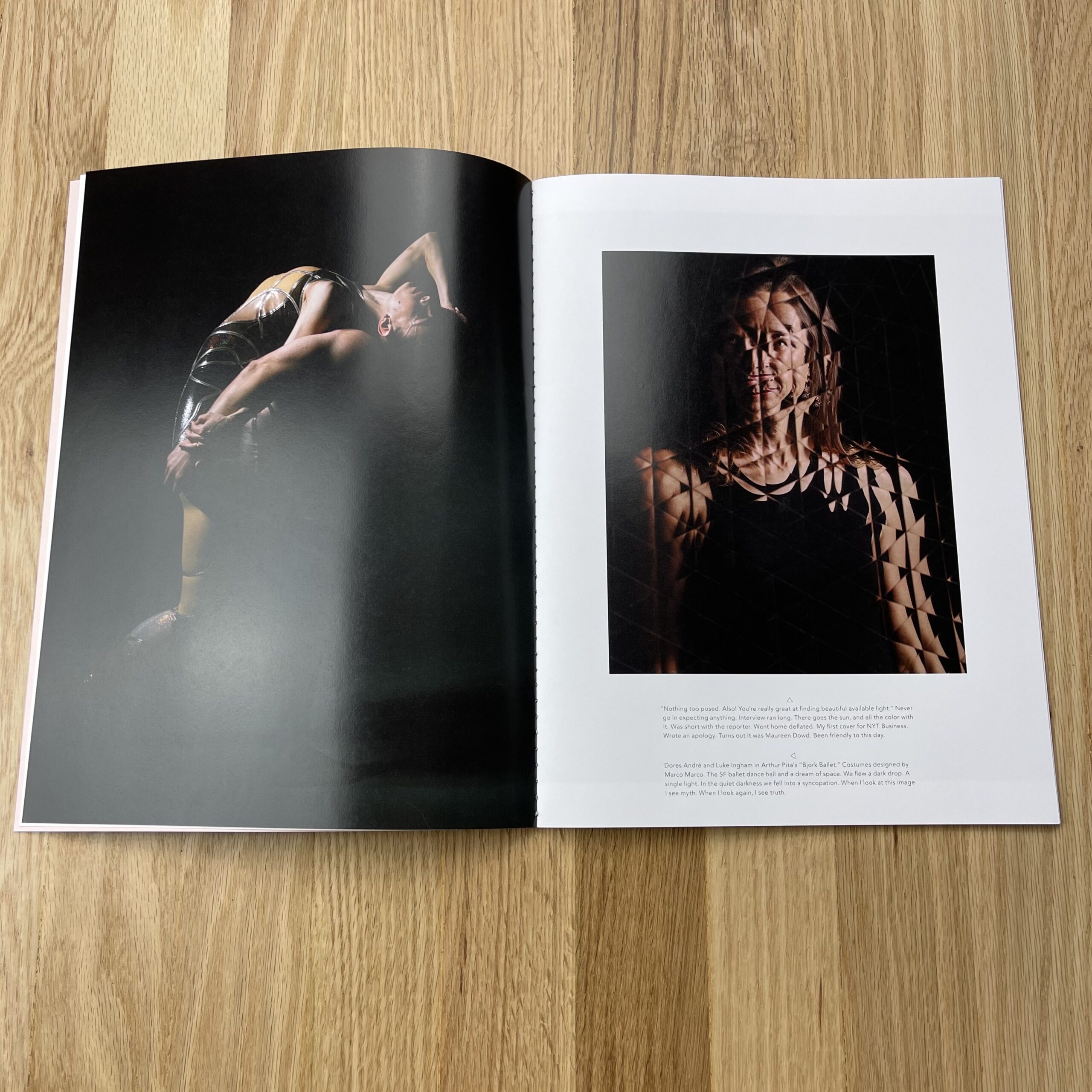

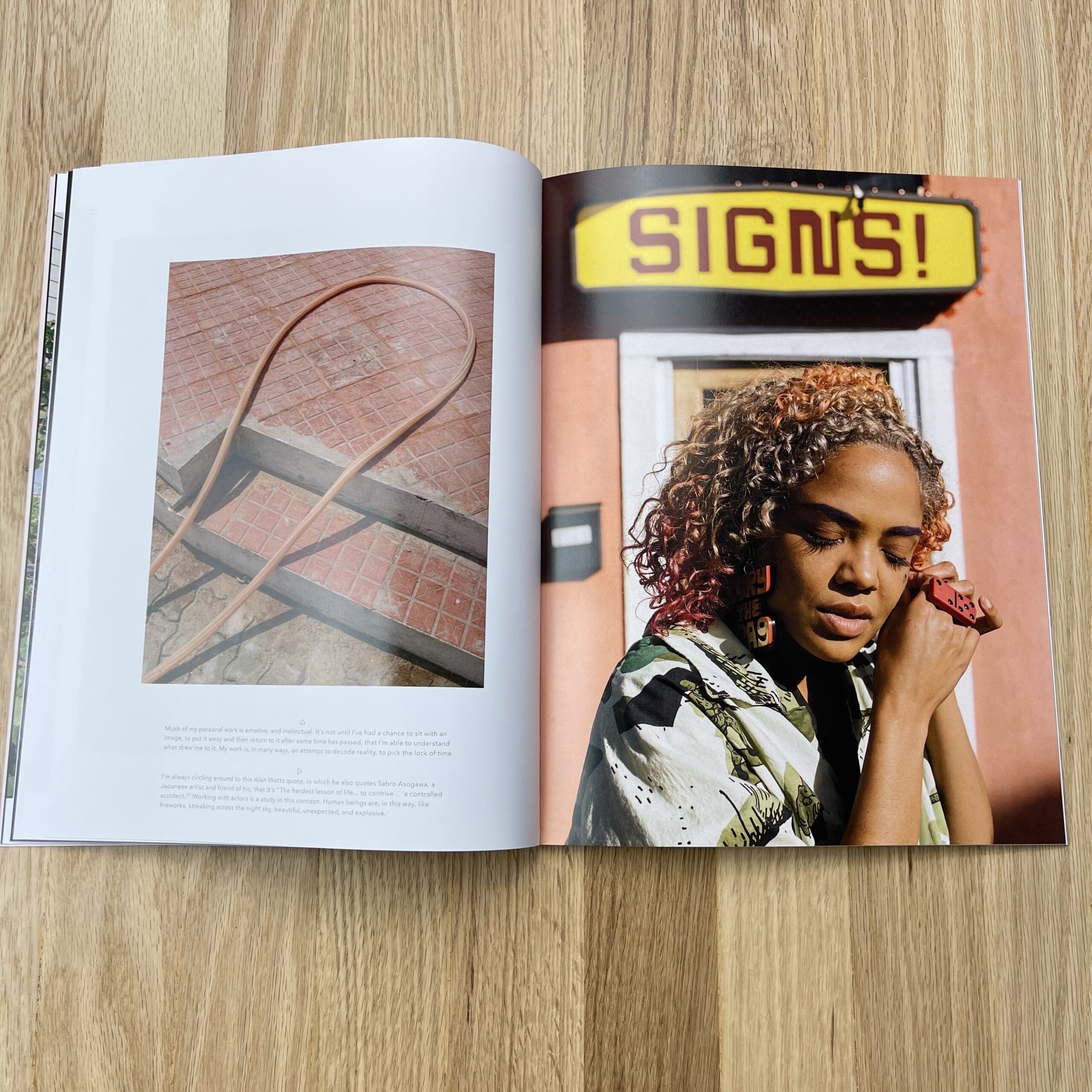

Photograph by Kat Castro (2021)

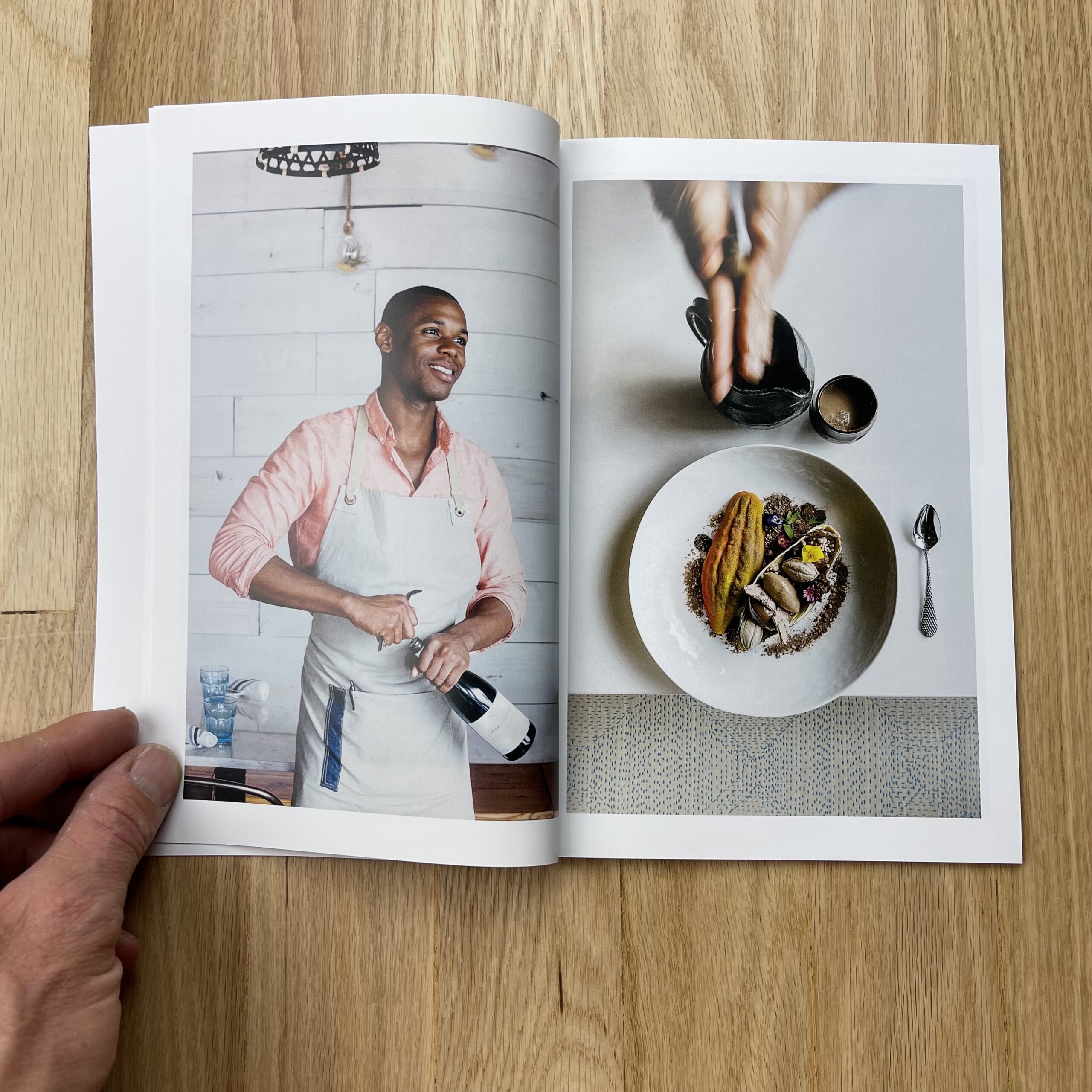

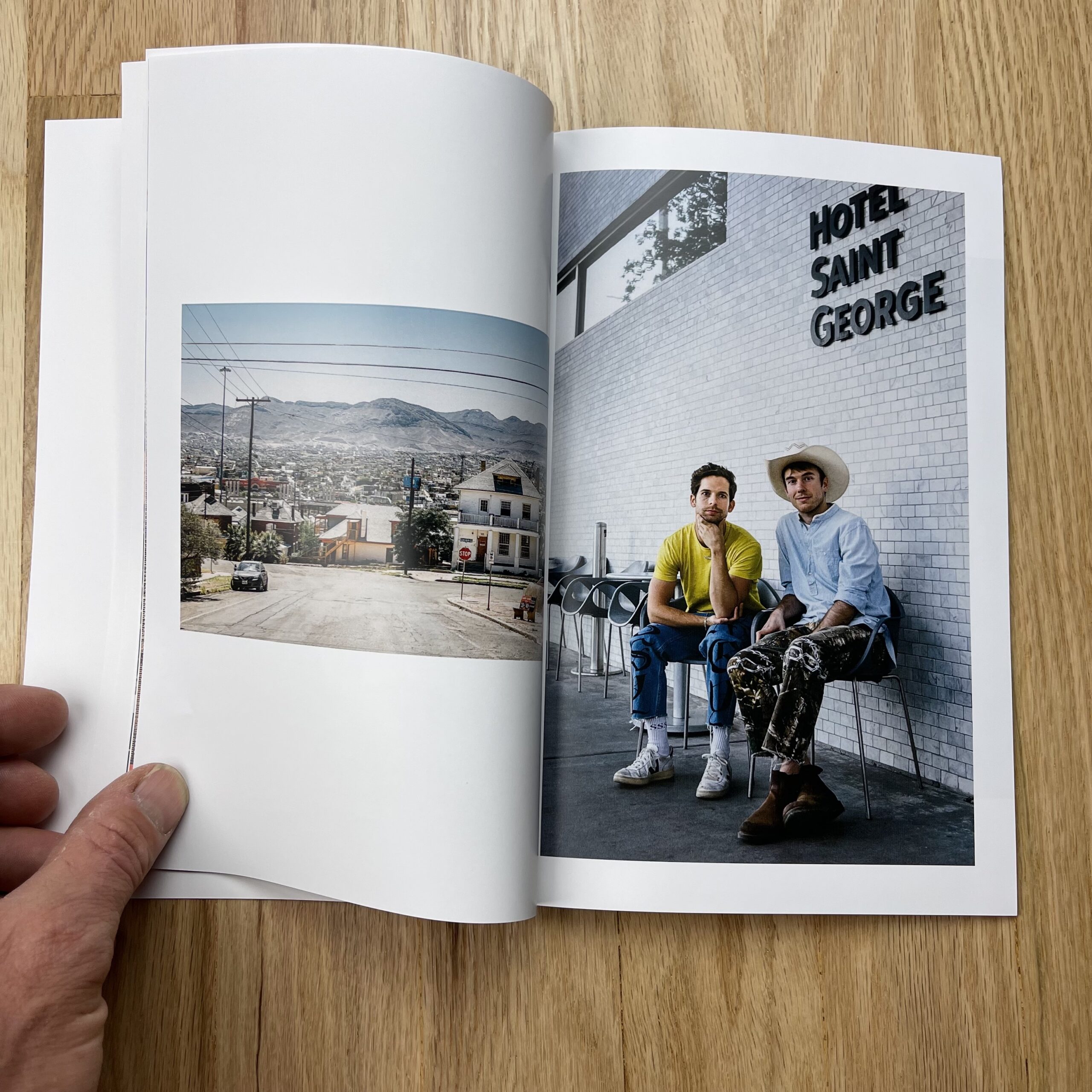

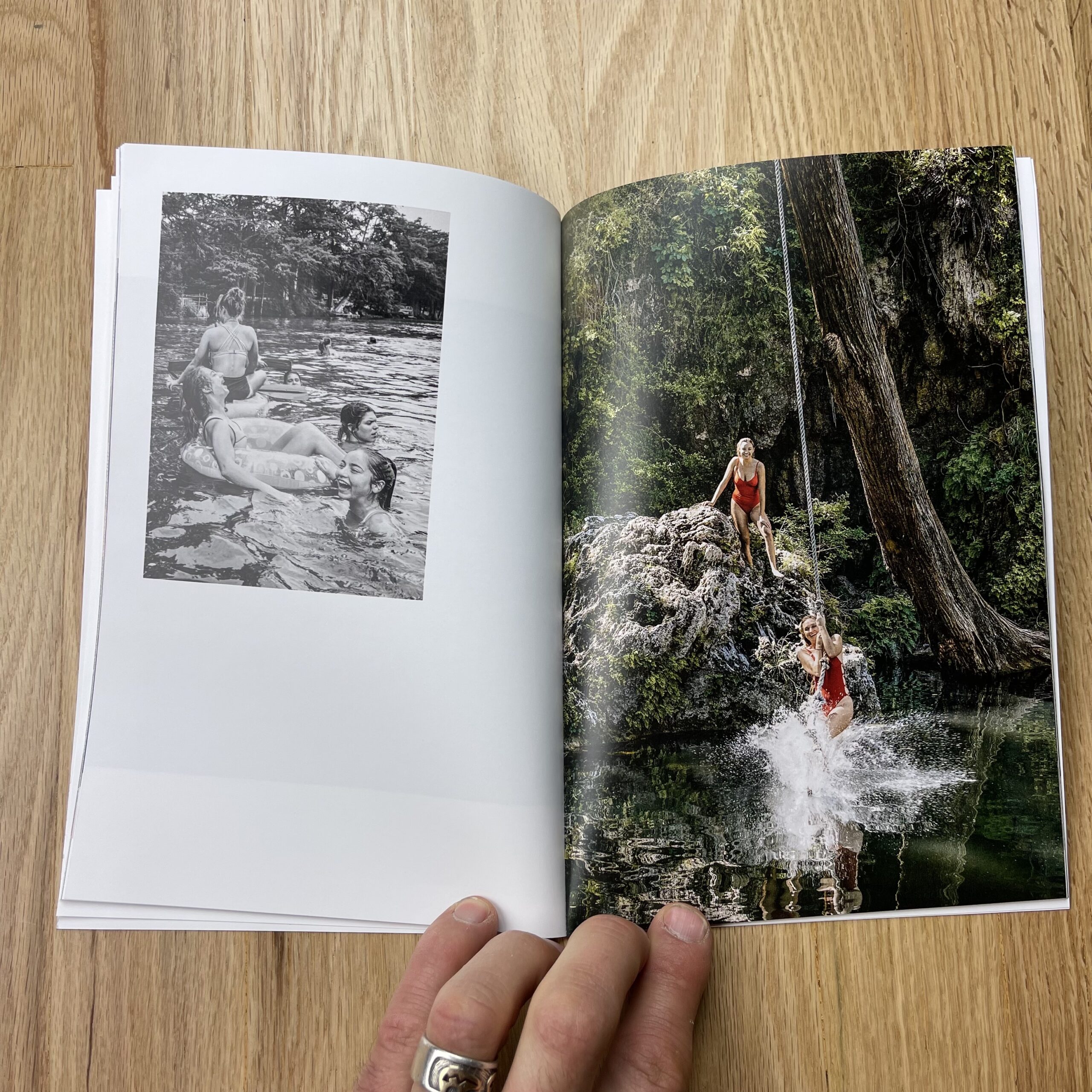

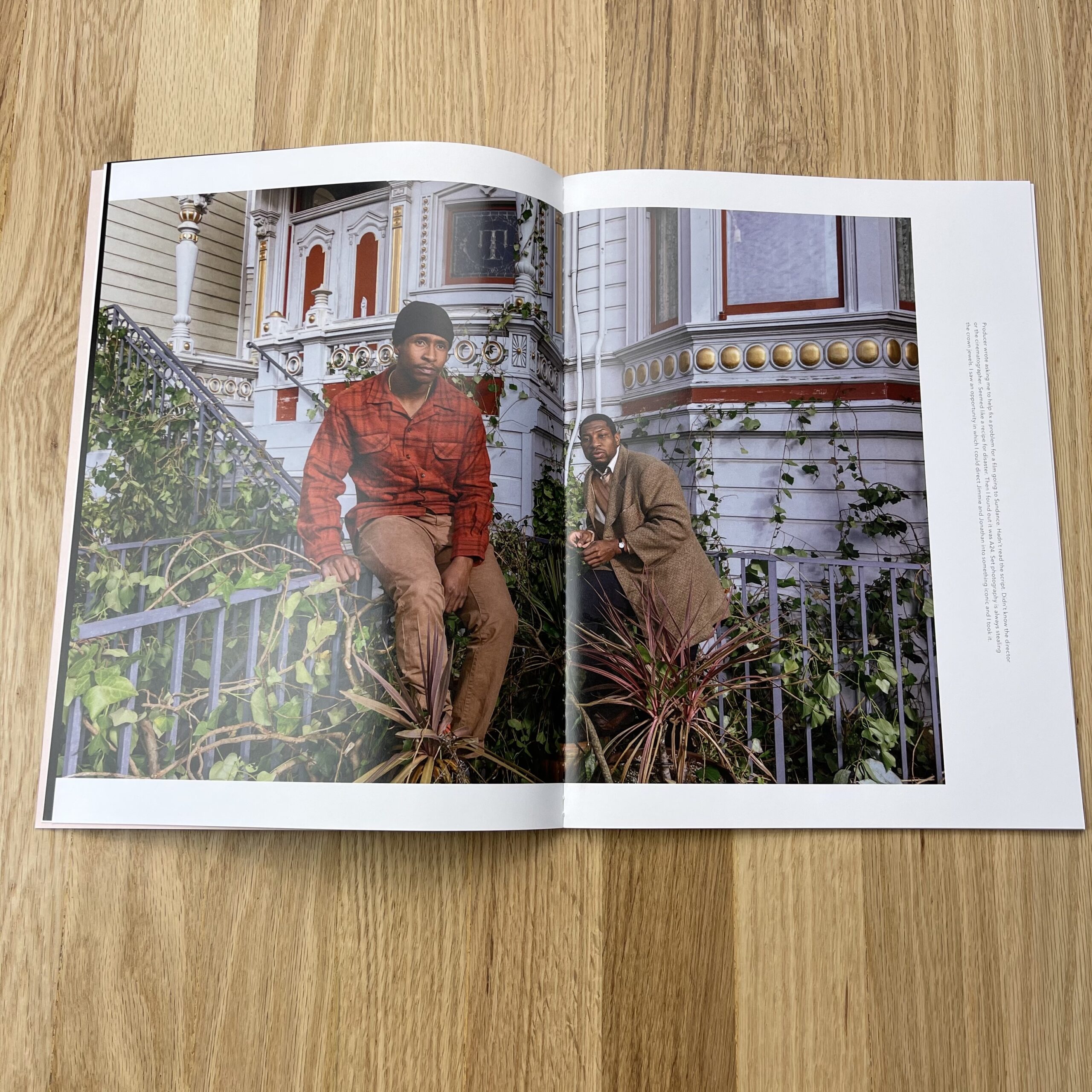

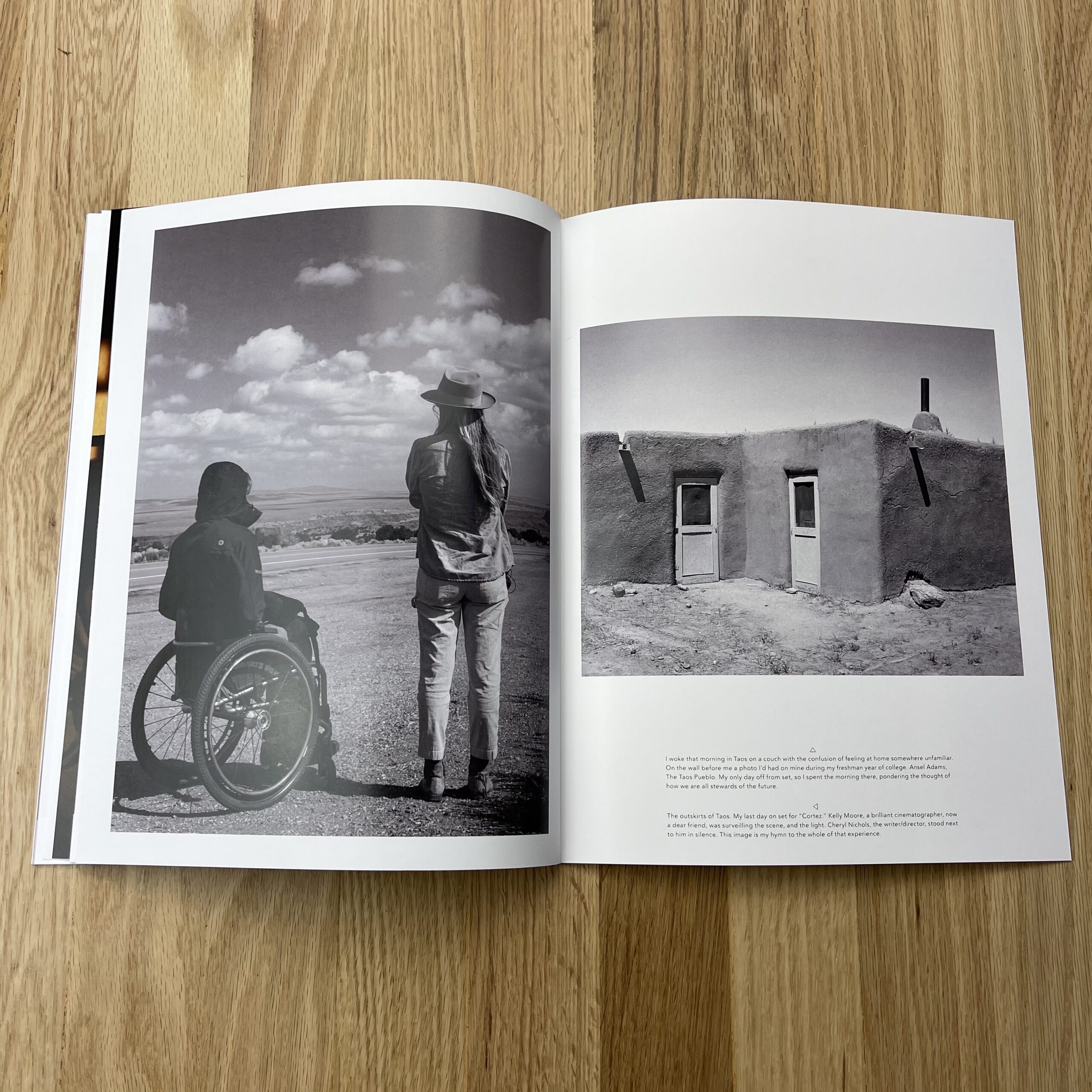

Photograph by Mark Gallardo (2021)

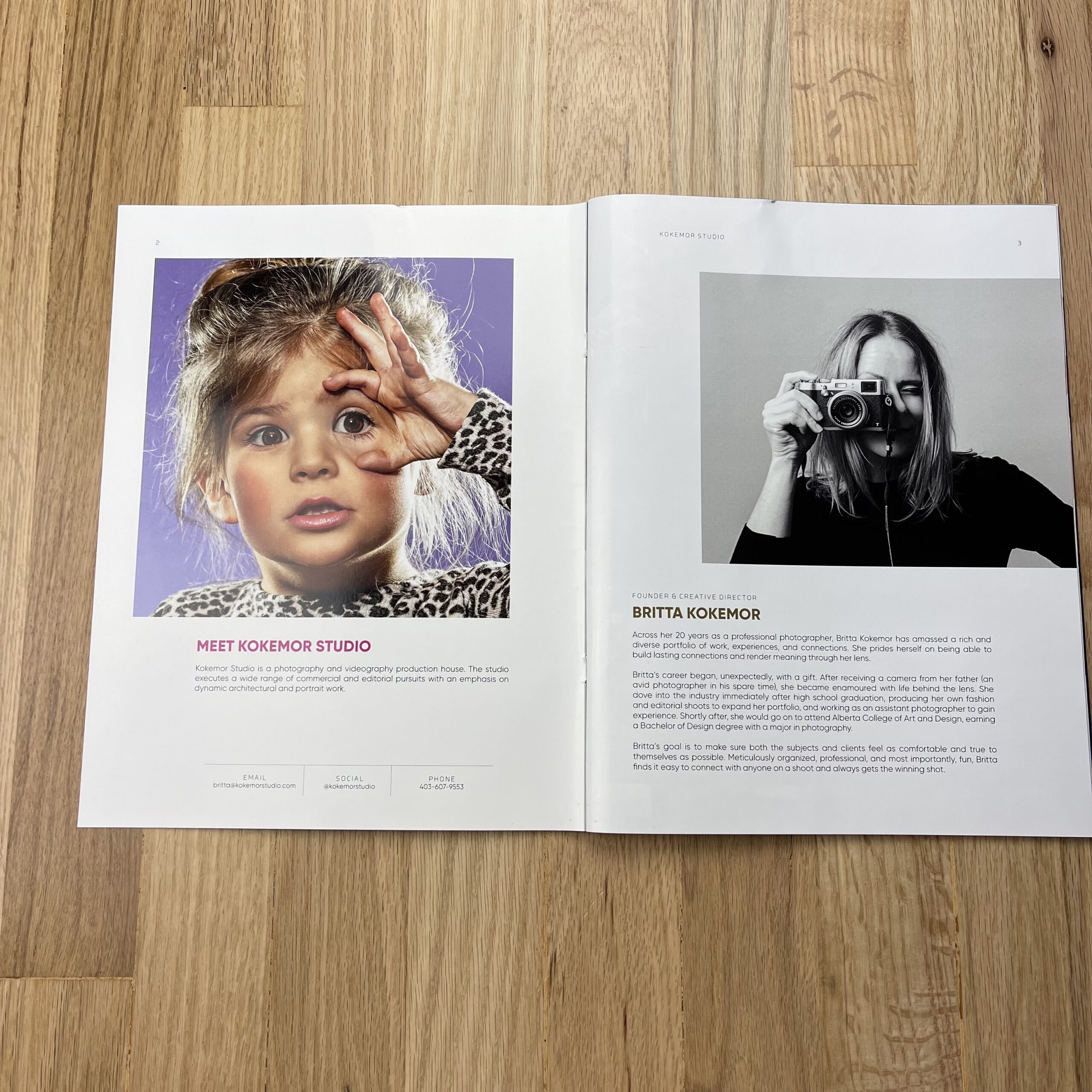

Ecru

Founders: Pam Lau and Jimmy Vi

How did you and Jimmy meet and is this your first collaboration?

Pam: Jimmy and I met at a photowalk in 2016. At the time we were part of two different grassroots community arts groups in Toronto. Over the years I watched him quit his job as an art director in advertising, teach himself filmmaking, and transition into a music video and commercial director.

In 2019 we loosely explored starting an agency together and called it Ecru. We ran into the typical problems; we lacked strategy and direction. We were all creative people and we had no business dev, ops, or finance. We were just friends that wanted to work on projects together. One of us, Kerwin, ended up branching off and starting his own creative studio

Jimmy and I decided to pivot Ecru away from creative services and instead focus on mentorship and community building.

Tell us about the name of the program.

Jimmy came up with that one. It was 11:55 p.m. We had just spent something like 10 hours working on the grant application, and we had five minutes to come up with a name before the deadline closed. We started rapid-fire brainstorming options and this one was short and catchy enough.

How did this free program come about?

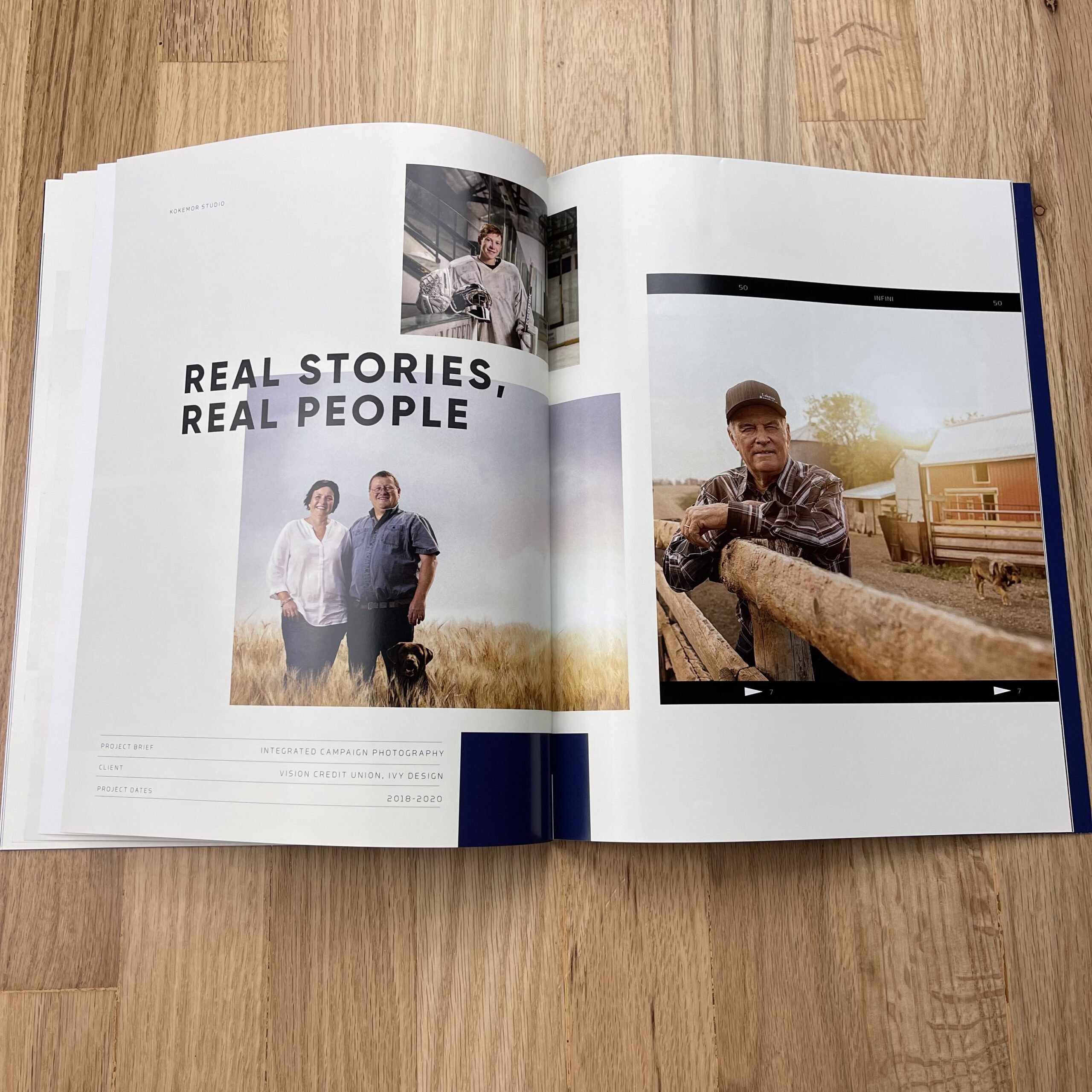

We applied for a grant through ArtReach; a funder via Toronto Arts Council and the City of Toronto mandated to support high-quality arts-making programming for marginalised youth. It took us three tries; the first two years we were rejected. After each time we sought feedback and reworked the program and in 2021 we received funding to pilot the first cohort of ‘Ideas From I’.

The 2021 grant covered 5-9 participants. We received funds from a private donor and were able to expand to 12 participants and offer mico-grants to put towards development of the concepts they made the treatment decks for in the program. This year we’ve received the next phase of funding from ArtReach and have a partnership with Gallery 44 in Toronto where participants can get access to studio space and gear to shoot their projects in the Fall.

How did your career in photography get started and what are you hoping to build with this program?

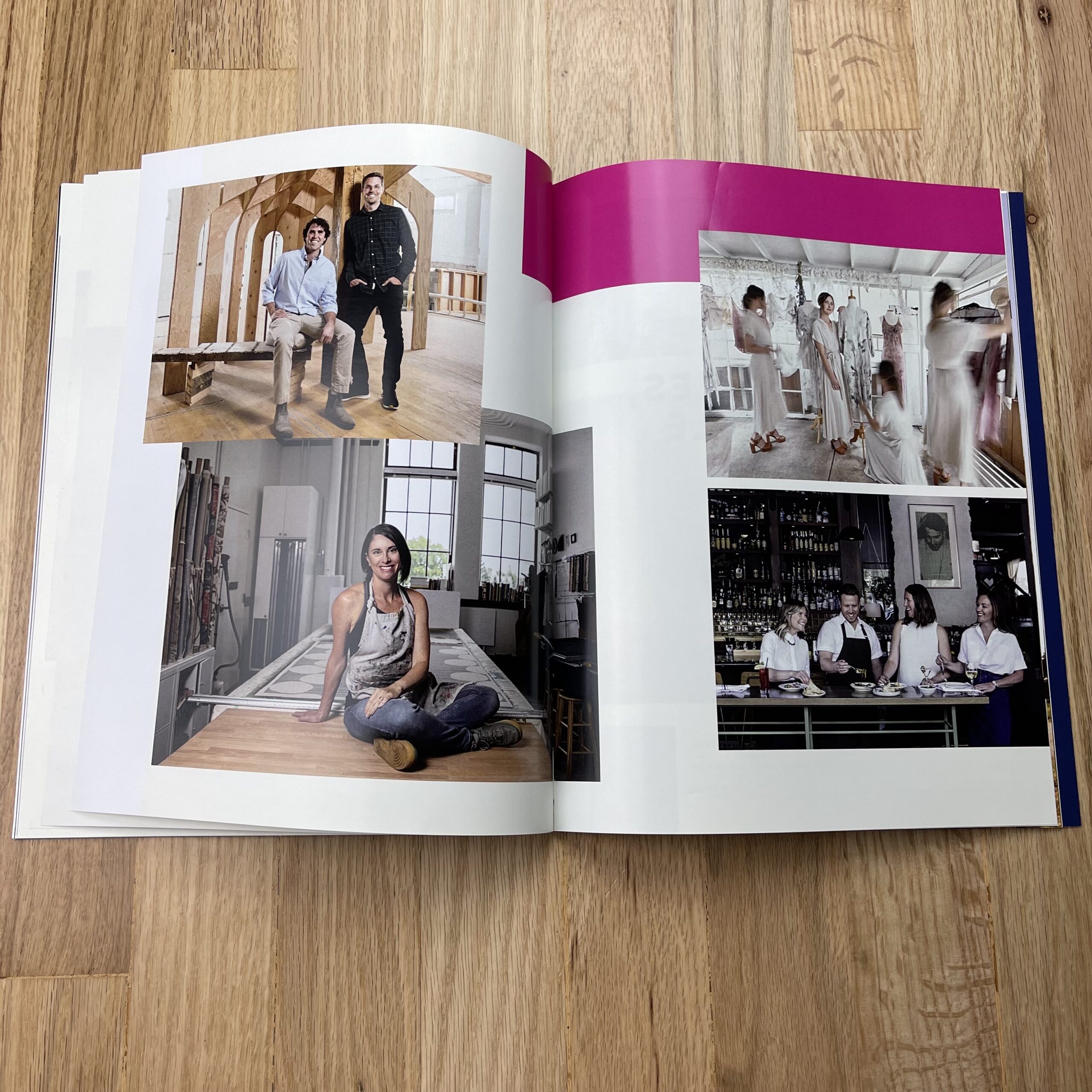

I’m self-taught and started taking photos in high school, never thinking that I could turn it into a career. I started freelancing during school because I always had a camera on me, and after graduation, I started working at a trade publication called Marketing magazine (acquired by Strategy magazine) that reported on the Canadian marketing, media, and advertising industry. I got to sit in on CDs deliberating over what creative was award-winning and I started to build my network from the conferences and trade shows that I covered.

It was very lonely in the beginning of my freelance career and I felt like I had nobody in my corner. Jimmy and I talked about the stress and high-pressure we put on ourselves to make it work, when it felt nearly impossible. I’m starting to recognize it now as a lack of internal validation after growing up feeling guilty or divergent for wanting something other than what others expected of me. The words “You can do it” and “I believe in you” are extremely powerful when said earnestly. With this program we want to be that extension of support that our younger selves lacked for the next generation.

How does one get involved?

Follow us on Instagram (@ecru.club), check out the application form, and send it to someone who comes to mind. We’re also looking to bulk up the micro-grant portion and are open to sponsorship and donations from individuals, production houses, agencies and brands that identify with the goals of the program.

application form is here

Where can find out the specifics of the program?

We’re sharing the application form, testimonials from alum, and answering questions this week on Instagram at @ecru.club.

What does the program offer?

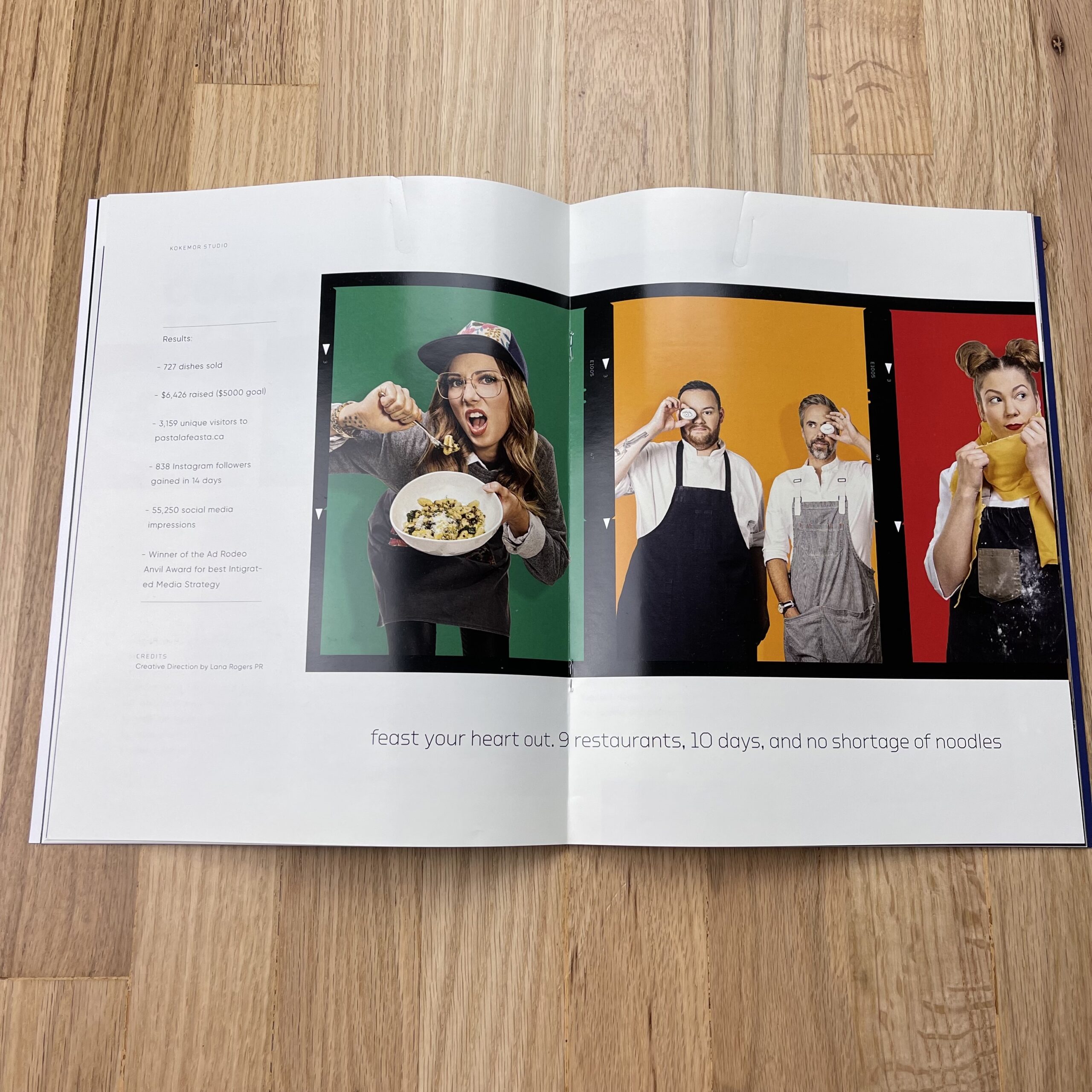

As photographers and directors, vision and concept is at the core of what we do. ‘Ideas From I’ teaches the importance of communicating your ideas through imagery and words. Participants learn about referencing and develop a concept by analysing and drawing a personal connection to what media and art they respond to.

We walk them through creating a treatment deck and effectively pitching it, and support them through the groundwork of pre-production by offering the resources for them to bring their idea to life. We support a range of experience because even if you don’t know how to technically execute something yourself, you can find collaborators and bring a team together that can make it happen.

Most of all, we’re doing it in an environment where we want participants to feel seen, heard, respected, and validated.