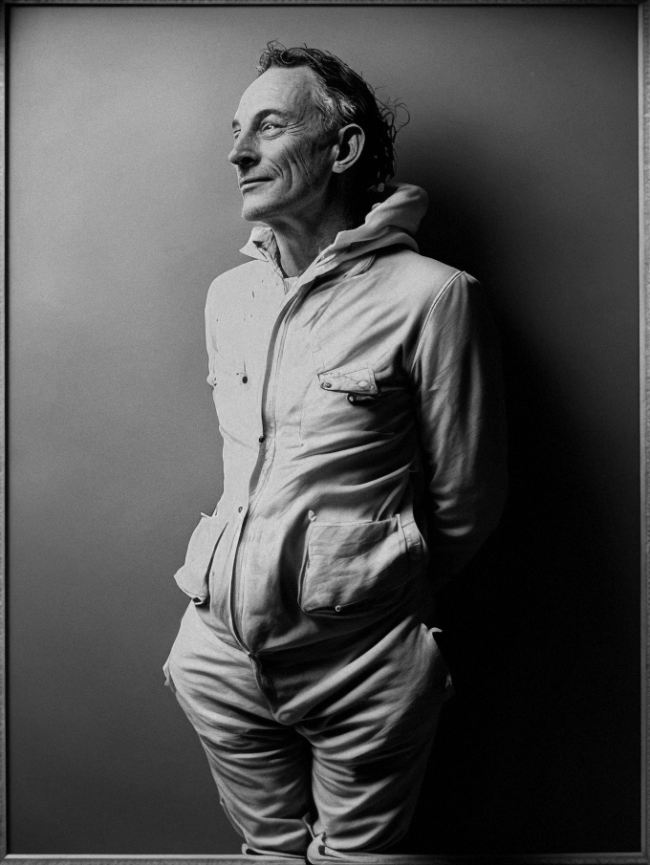

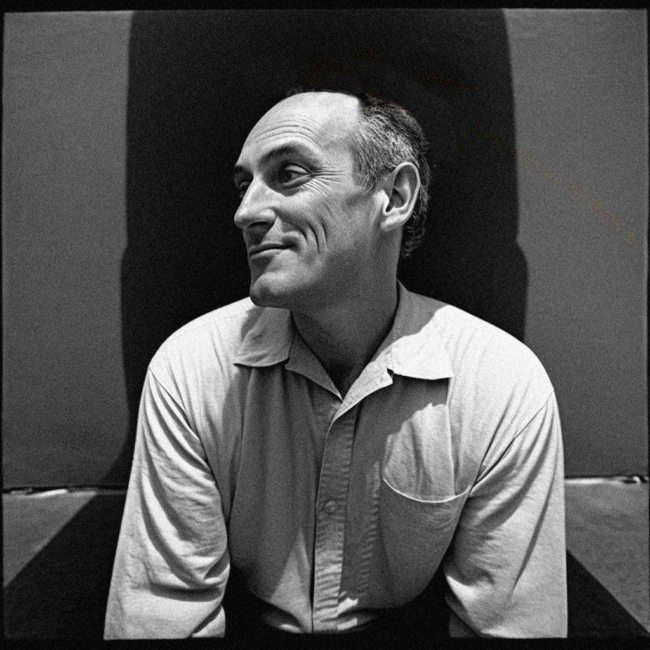

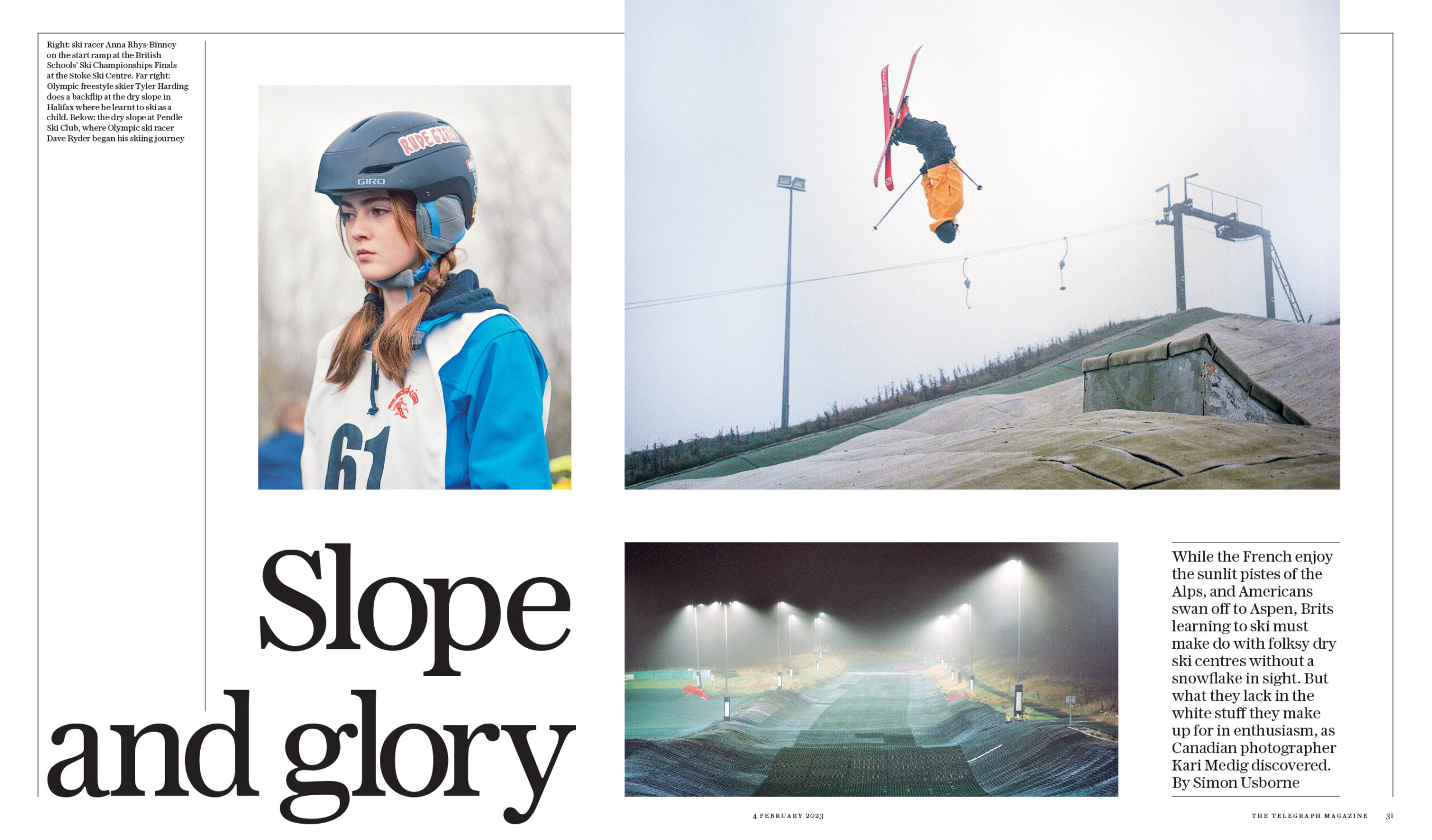

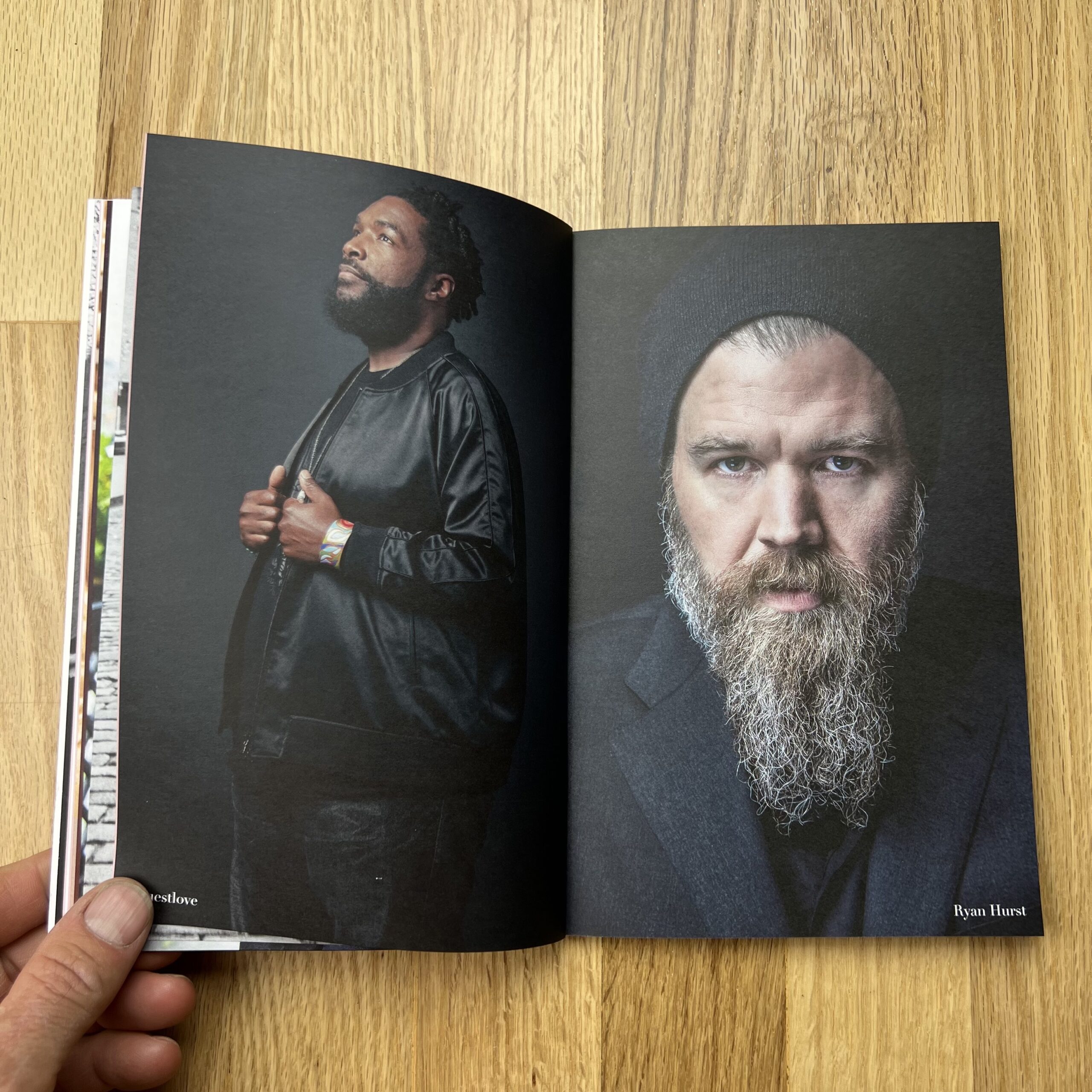

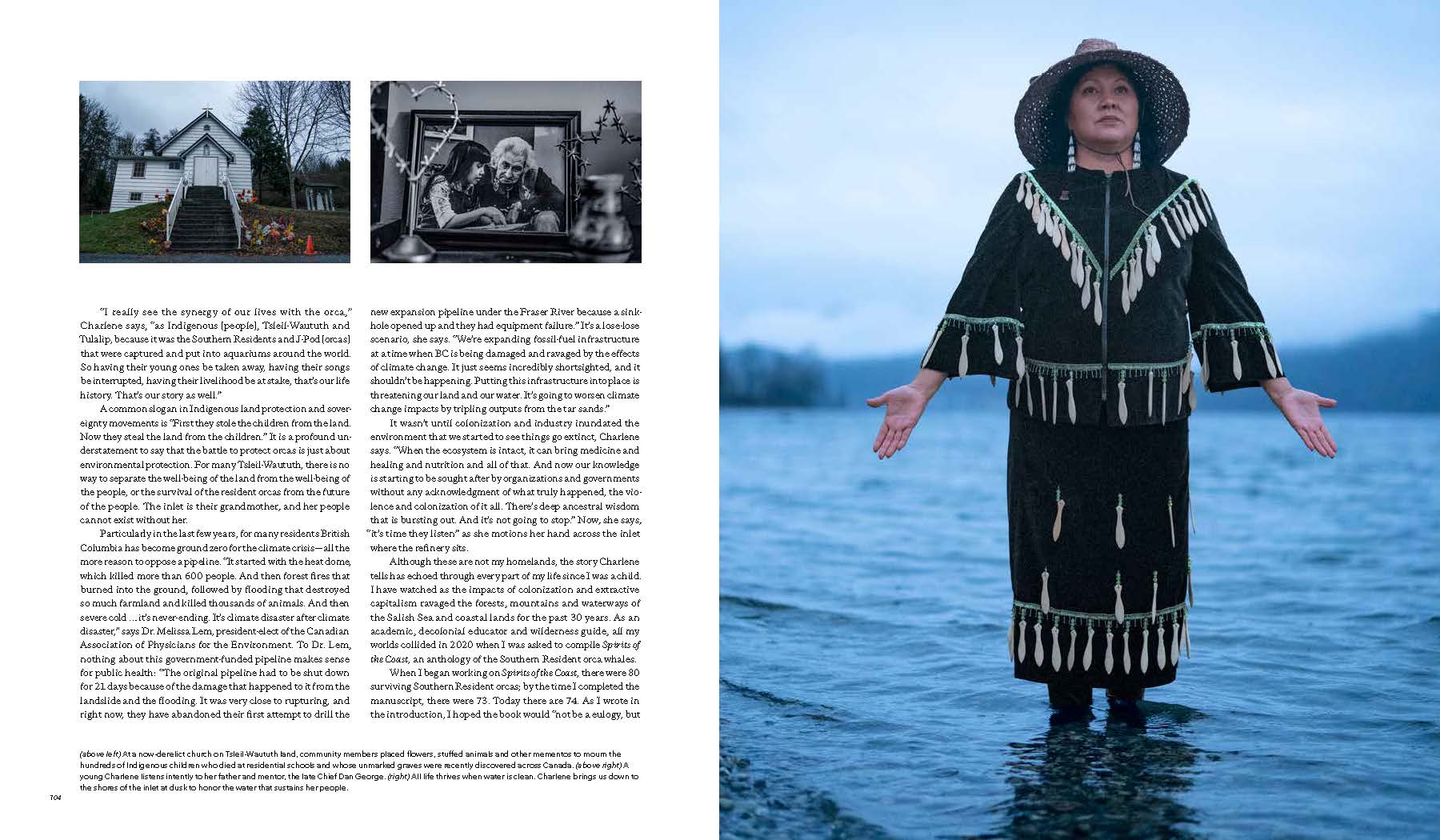

Ray Collins

Heidi: The ocean is a dynamic canvas, what made you what to create a stillness?

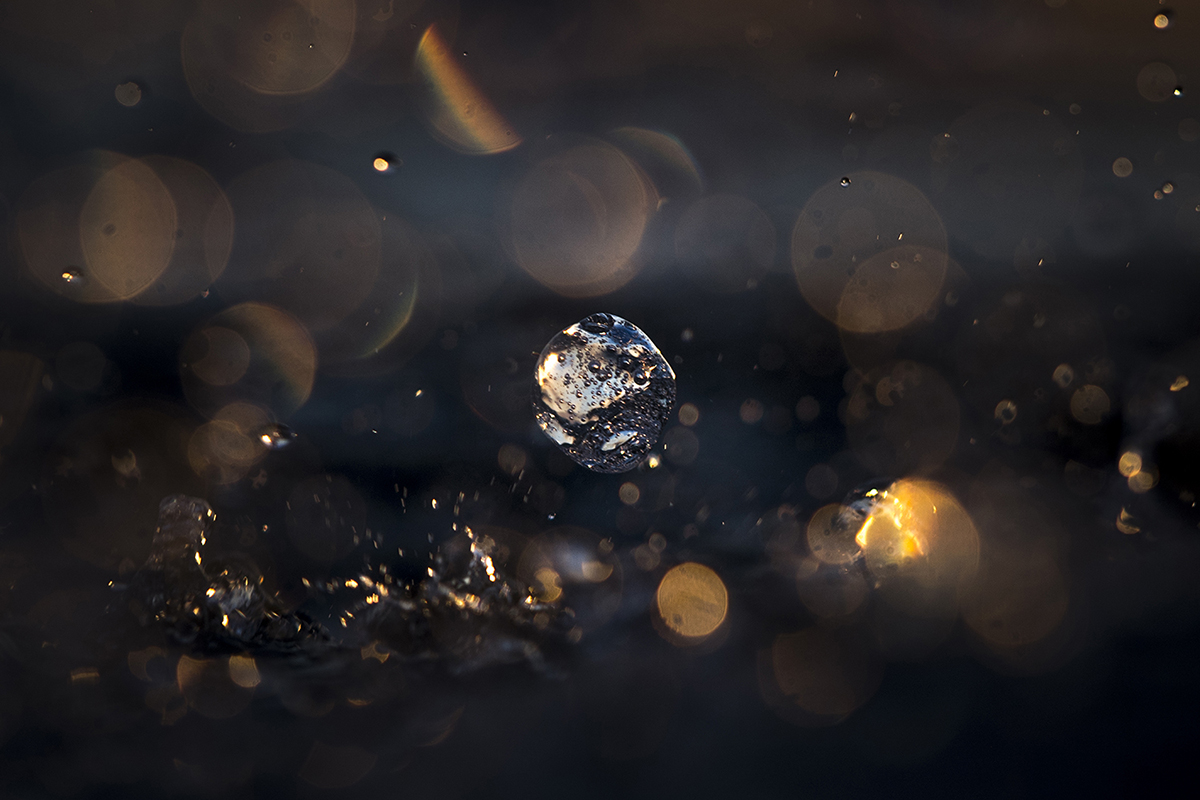

Ray: I want to freeze the moments that we may miss in real time. Sometimes the anticipation of a rising swell of what ‘might’ happen is more important than the finale of the crashing wave. It’s often the moment before the moment which becomes the moment. Anticipation makes you question what happens next, it provokes a response from the viewer, and that’s what art should do.

In a few sentences describe what the ocean means to you?

The one single constant in my life has been the ocean. It has given me everything I have, and the greatest lessons of my life have been learned from interacting with it. It has taught me: patience, courage, respect, going with the flow. I’ve made such a diverse pack of lifelong friends…our only common thread being saltwater. It has instilled a firsthand appreciation for nature. It’s shown me its power, beauty and purity—often all at once. It keeps no record of history; it obeys no law. It is the one ever-changing constant. I have traveled the world in pursuit of documenting it. Whenever I am near it, wherever I am, I am home.

How does being color blind inform your photography?

My theory is that because of the deficiency of color blindness it has potentially enhanced other parts of my vision (maybe composition and textures) and that could be something that helps make my photography unique? That’s my working assumption anyway.

Photography and the ocean came into your life as a form of healing from a coal mining accident where your knee was severely damaged, the camera came first, why? and what were you photographing?

I just needed an outlet. My routine of an active life in my 20’s had come to a stand still and I had a lot of time on my hands. Learning photography and how a camera works was something I never had time for before. So I just read and re read the manual and took photos of my dog actually. Trying to understand the relationship between Shutter, Aperture and ISO and moving her (Chantic) near different windows at different times of day, she was such a loyal dog. An old soul. I have her name on my foot.

After a few weeks of knee rehabilitation my physio said I could introduce some light swimming into my routine. So I bought a waterhousing for my camera and started shooting photos of my friends surfing. Within a few weeks I had my first published image, within a few months I had my first international cover.

When did you understand this is what you were meant to do?

There were so many gentle course corrections and life affirming milestones that kept me on course and reinforced to me that I was on the right path

In the Patagonia film, Fish People, you mentioned planning a single shot for 6 weeks. In that planning are you returning to same spot to study the light movement?

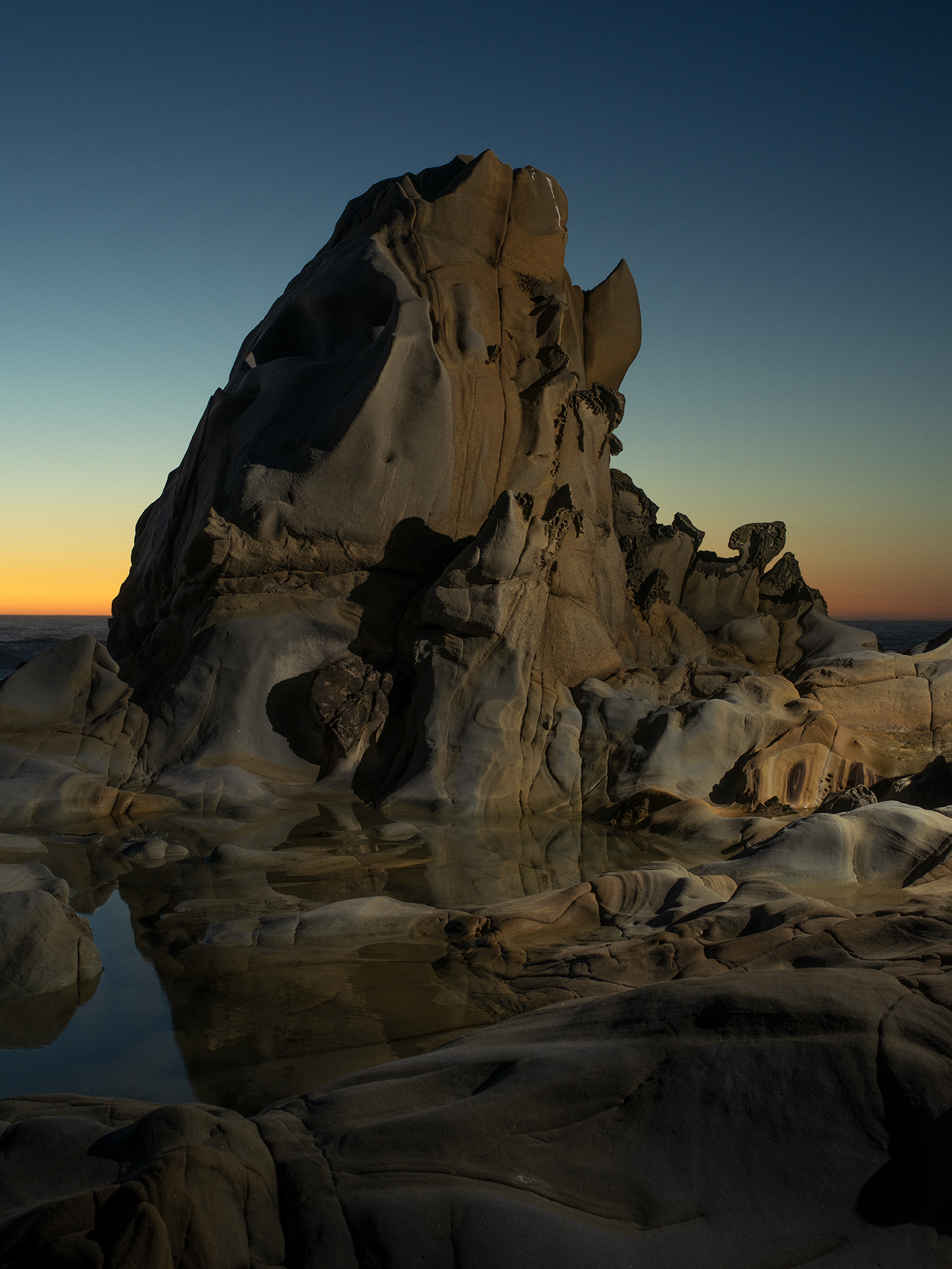

Sometimes! Fortunately I’ve found some good sun tracking apps that help with light source positioning. Another important detail is the tide, sometimes I need an absolute high tide (studying the moon phase helps) otherwise the reef might be sticking out of the water at a lower tide and the wave won’t have a clean curve. Then of course, the right swell direction and period – keeping my eyes on how distant storms are tracking. Oh, and wind. Come to think of it, sometimes many variables need to line up all at once. Pushing the shutter button down is towards the end of the creative cycle.

Not all images have that level of planning though. Sometimes just waking up with no plan but meeting the sun as it rises over the horizon is all it takes too.

What would you tell your younger, creative self now?

The best advice I got early in my career was shoot what you want to see, not what you think others want to see. It’s kept me on my own path and I would retell my younger self the same thing. I’d love to tell young Ray ‘you’re enough’ and you will have all of the desires of your heart.

How has your eye changed over the years?

I try and do as much as possible in camera, it makes everything easier down the track with editing. I’m always aware of divine proportions while composing and cropping and I always try and highlight points of interest within the image for people to discover as they peruse each piece.

How are you staying buoyant in the water to get those waves, flippers and swimming like hell?

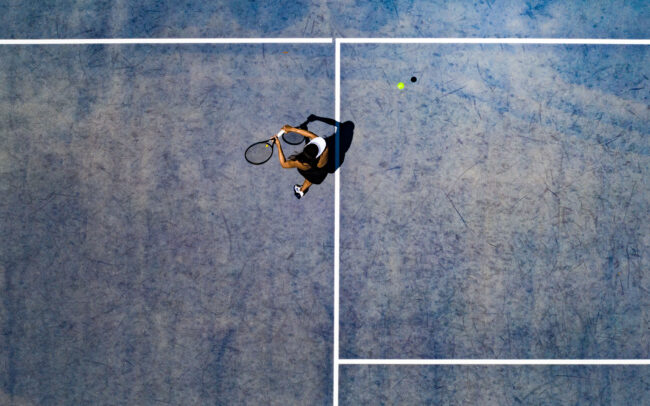

Most of the time I’m swimming and a lot of the time it’s at sunrise or sunset. The golden hour. That means swimming out in the dark and waiting for it to rise most mornings. A lot of the waves I document aren’t your typical user friendly beaches, often I have to scale down cliffs or swim way out in the middle of nowhere to find these weird and angry lumps of water breaking. What I search for are shallow reefs that are surrounded by deepwater, that way the wave traveling stands up suddenly in reaction to the shallow reef and that’s where I try to position myself. It’s the line between order and chaos.

Imagine swimming in a washing machine with a bag of concrete and lifting that bag up to your face so you can focus, compose the shot, getting all of your shutter settings, aperture iso right, getting no water droplets on the front element while the ocean is pushing, pulling, gurgling and crashing all around you. It can be physically exhausting at times. Your ‘studio’ can kill you, but it offers up some of the most precious moments of life in between.

I fail more than I succeed in overcoming it, but it makes the successes even sweeter. It’s always risk versus reward.

Working for yourself and by yourself can be a pretty selfish ride in a lot of ways and I needed to pursue a noble cause. Lifeguarding is truly a dream job. You’re being of service to your local community, being paid to stay in peak physical fitness and you get to work with an incredible team of likeminded folks. You get to help educate the public on the dangers of the ocean while being a caretaker and custodian of your local area.

I’m so proud to have amazing clients such as Patagonia. They’re the benchmark of everything that every other company should strive for!

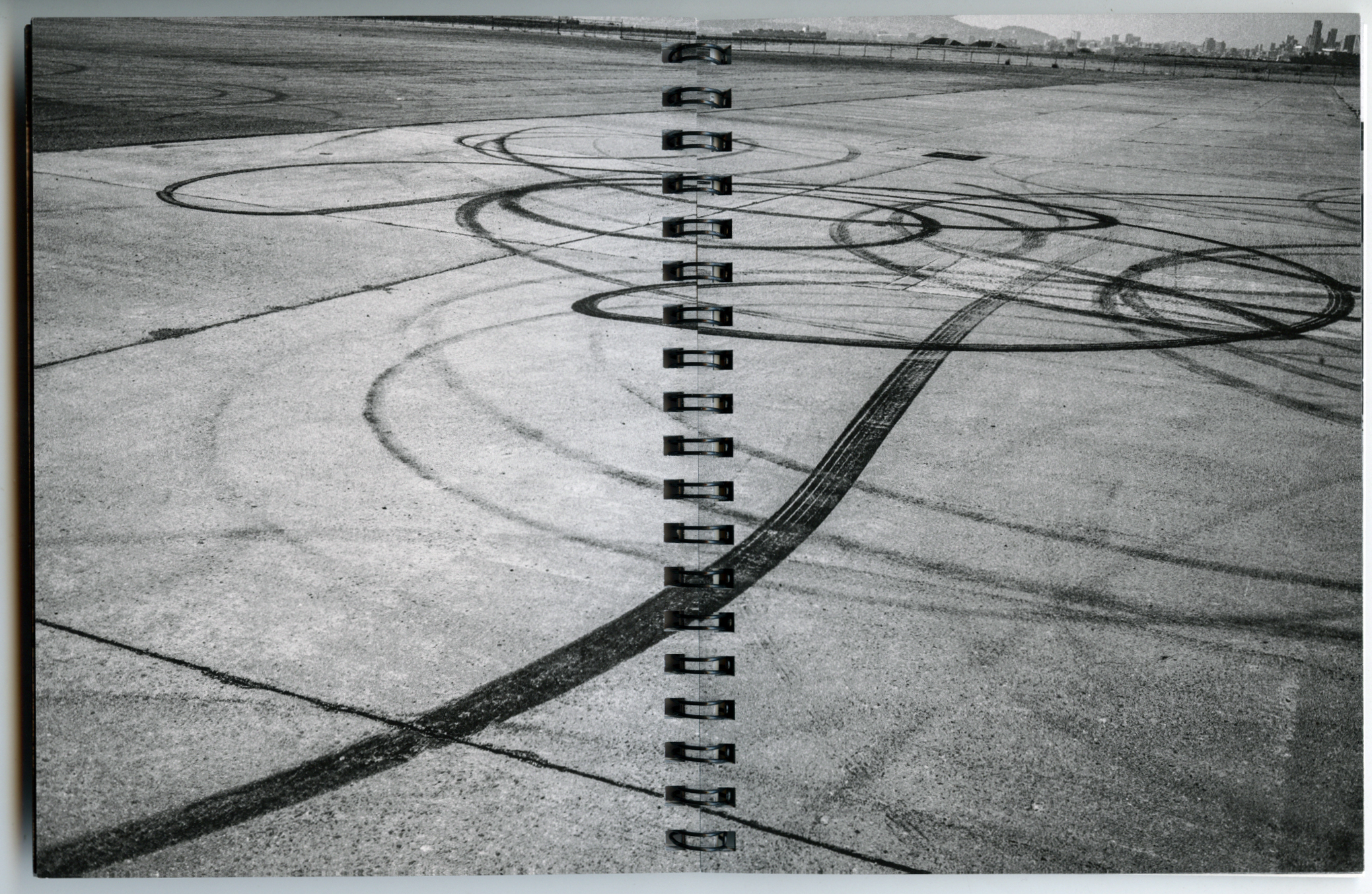

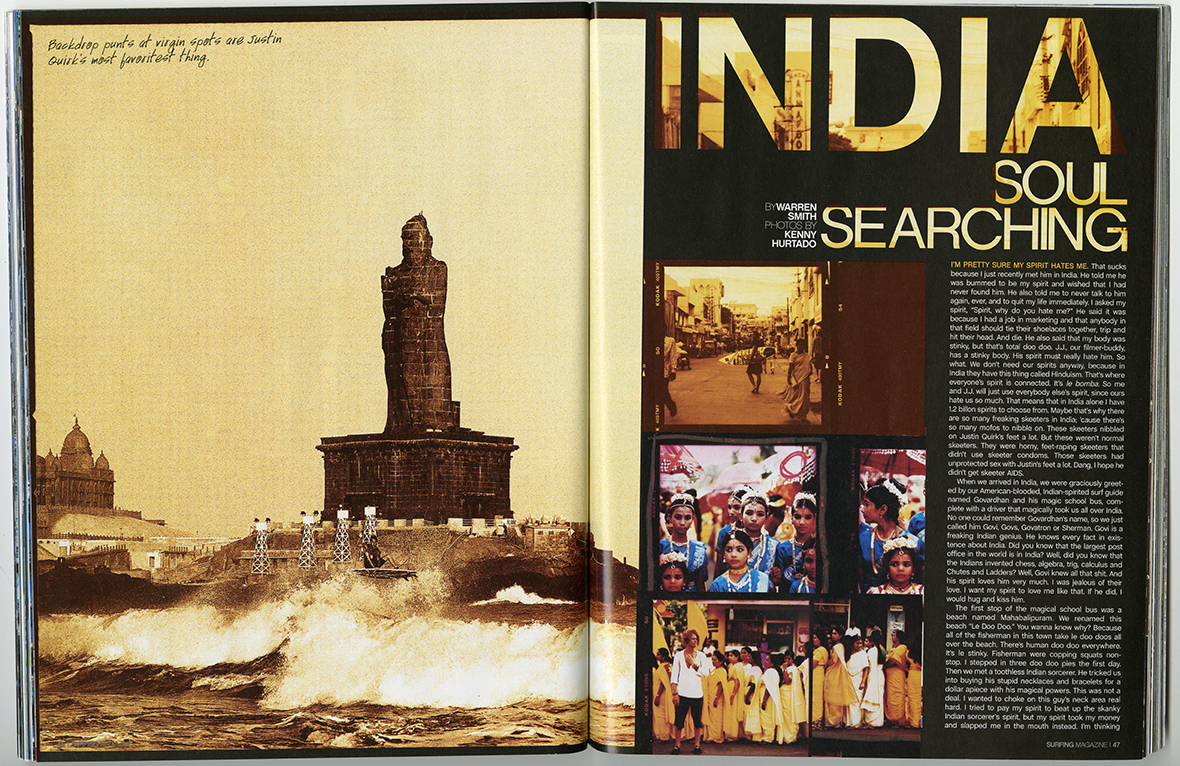

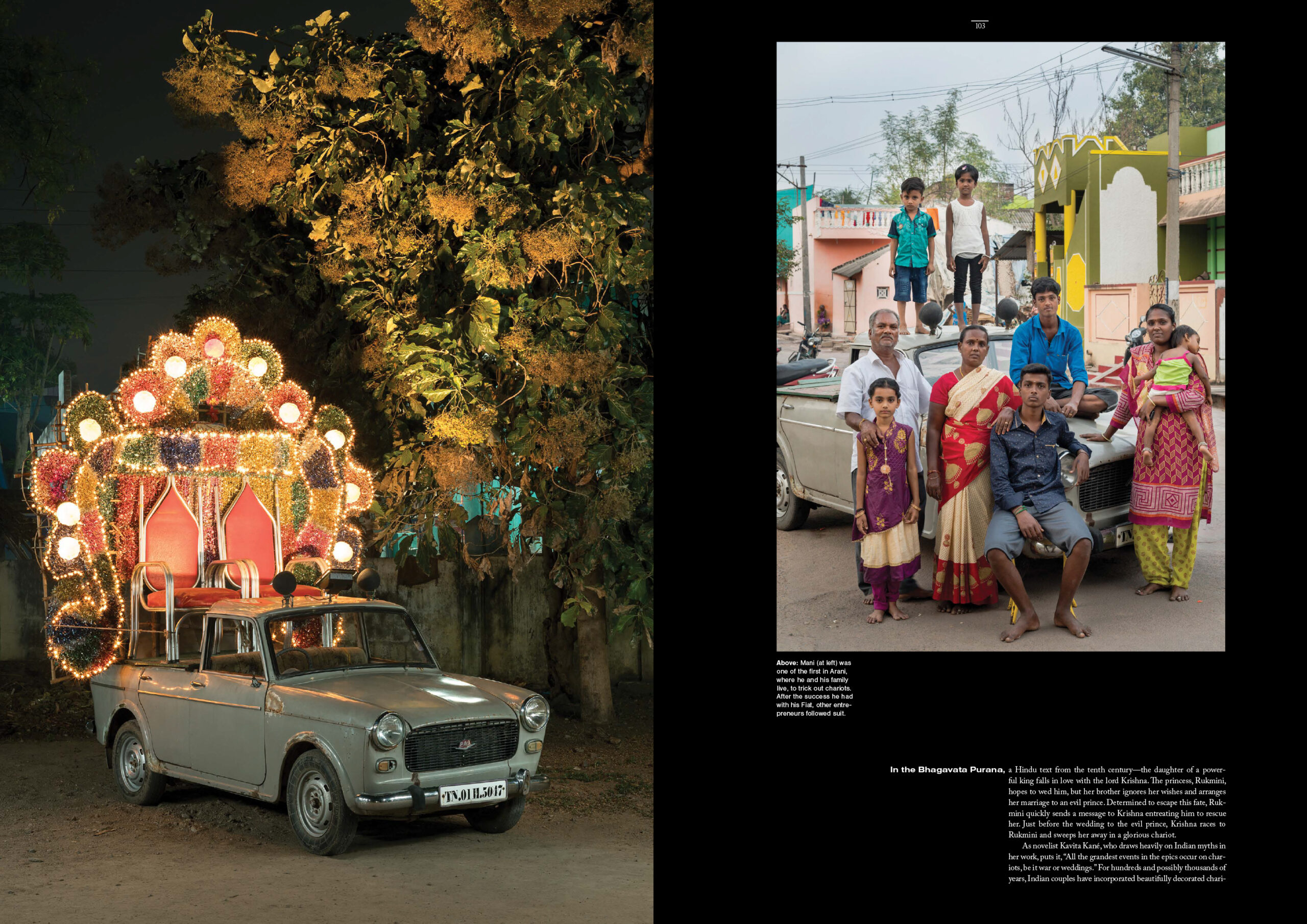

Journal cover – Convergence: I’ve always appreciated the birds’ eye view of the ocean, it feels like a forbidden vantage, one that humans were’t meant to see. Drones are pretty cool, but nothing beats hovering over the top of a large and powerful swell and isolating the ‘roof’ of the wave from above. It offers a whole new world of compositions to work with. It is not cheap however so you have to choose your days and make them count.