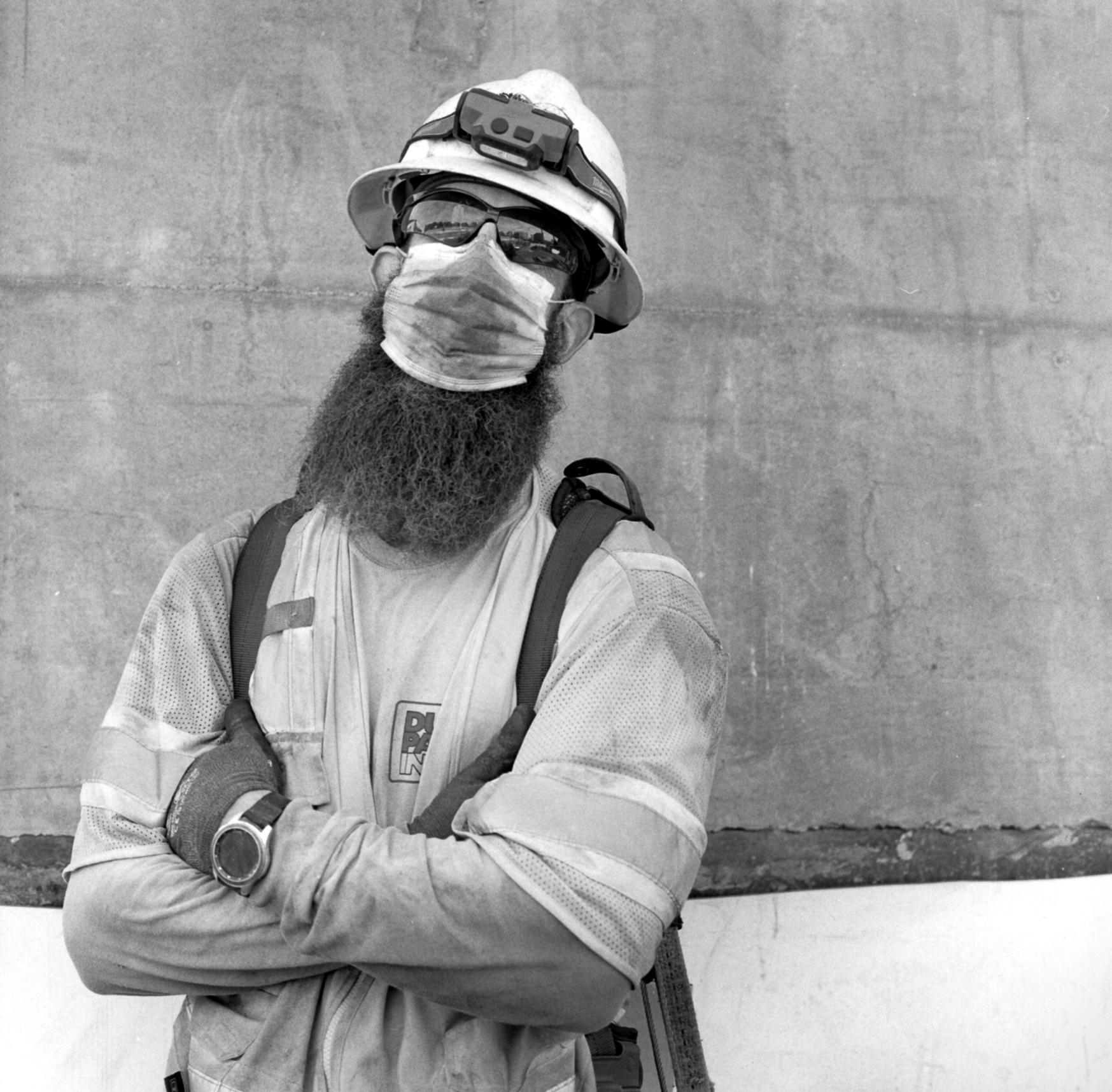

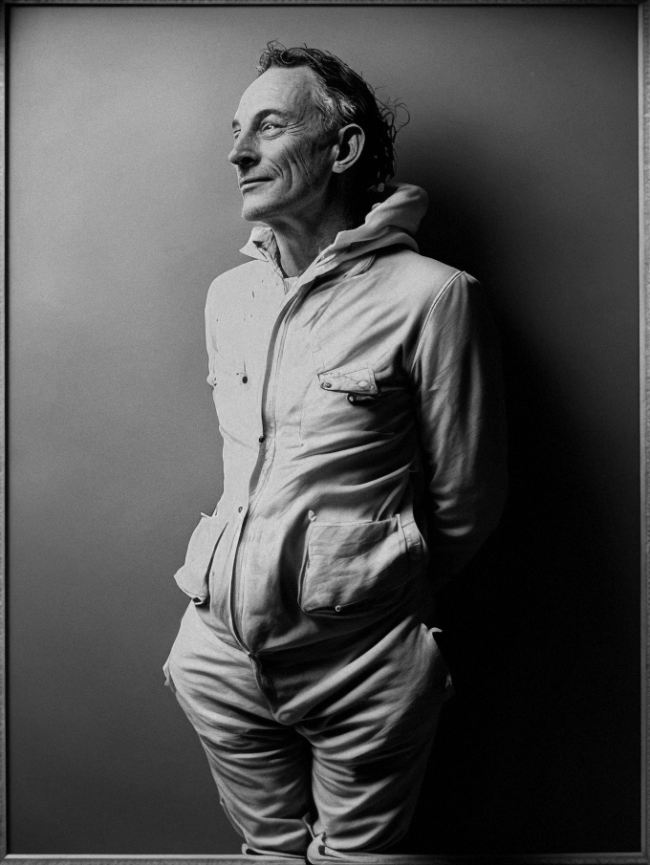

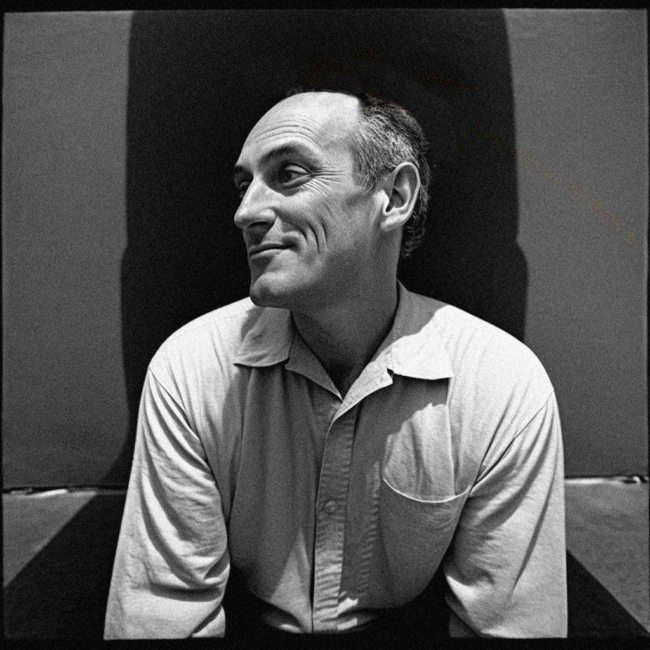

Ken Karagozian

Los Angeles Metro Art website showcases Ken’s work and a PDF around his body of work called Deep Connections

Heidi: Congratulations on your long and rich photo career, you had incredible mentors, what did each of them offer you that you still practice today?

Ken: Ansel Adams had an incredible impact on my interest in photography. On a high school photography field trip in the early 1970’s to visit Ansel Adams studio and darkroom it was my first experience seeing a beautiful B & W landscape print displayed on the wall at his home. I was just amazed the clarity of richness of a fine art print and then thought maybe that it something that I would like to emulate for myself in a making a beautiful print.

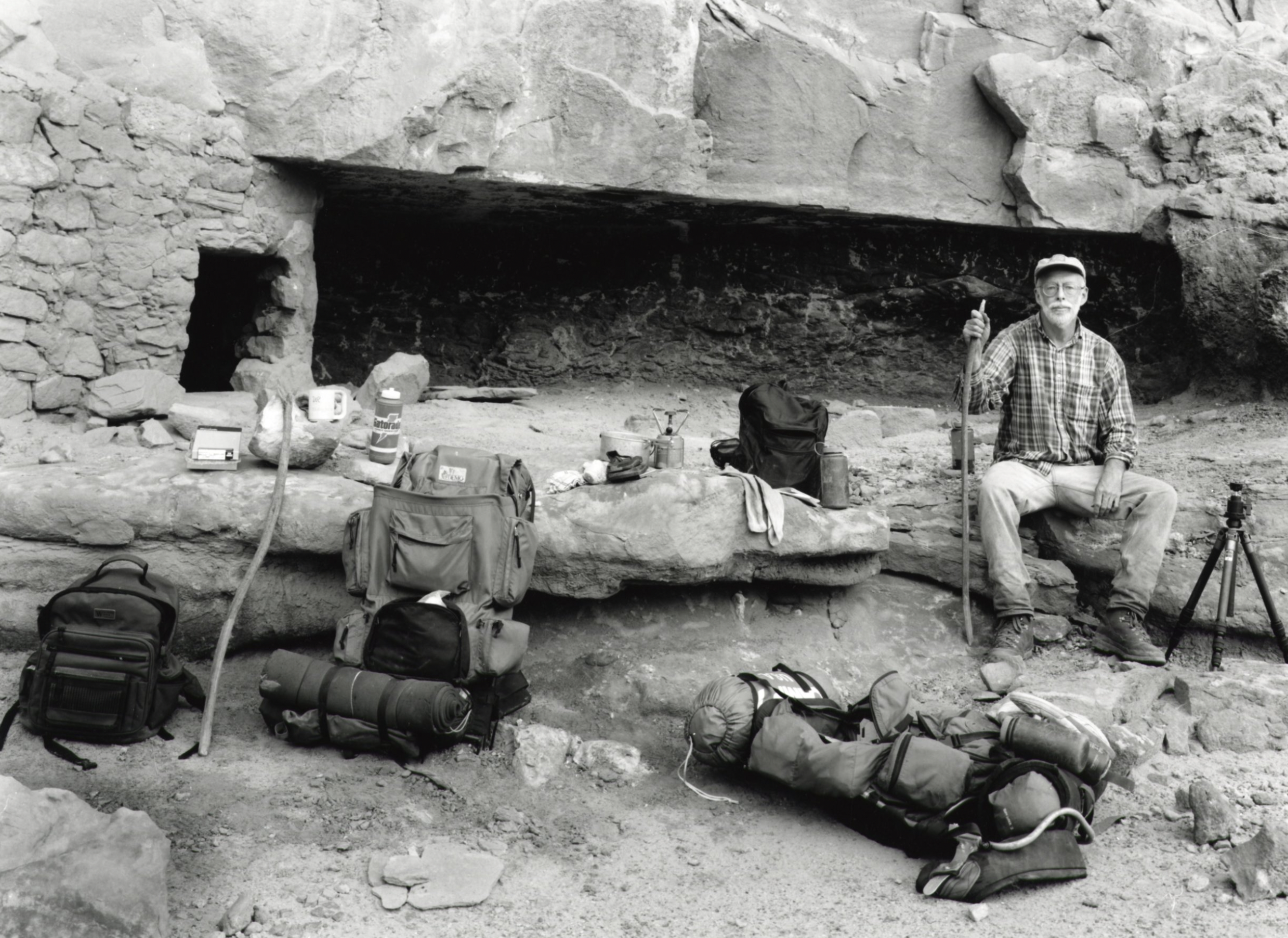

Another important factor that I learned in the 1980’s was when taking a workshop with the Owens Valley Photography instructors (John Sexton, Bruce Barnbaum & Ray McSavaney) that when you do a photography project that you have to always photograph in different lighting situations & seasons to really see the different changing of light upon your subject matter.

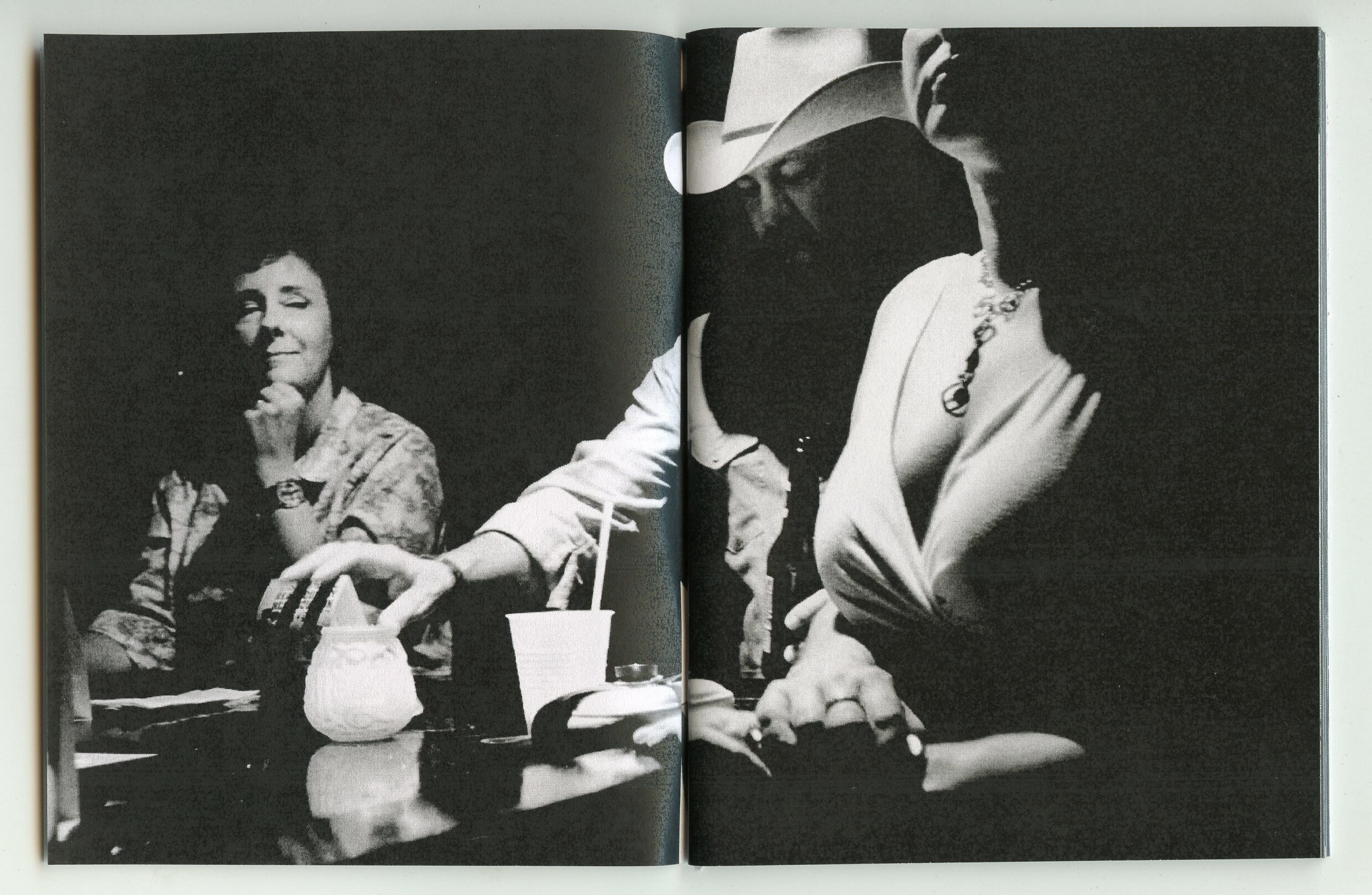

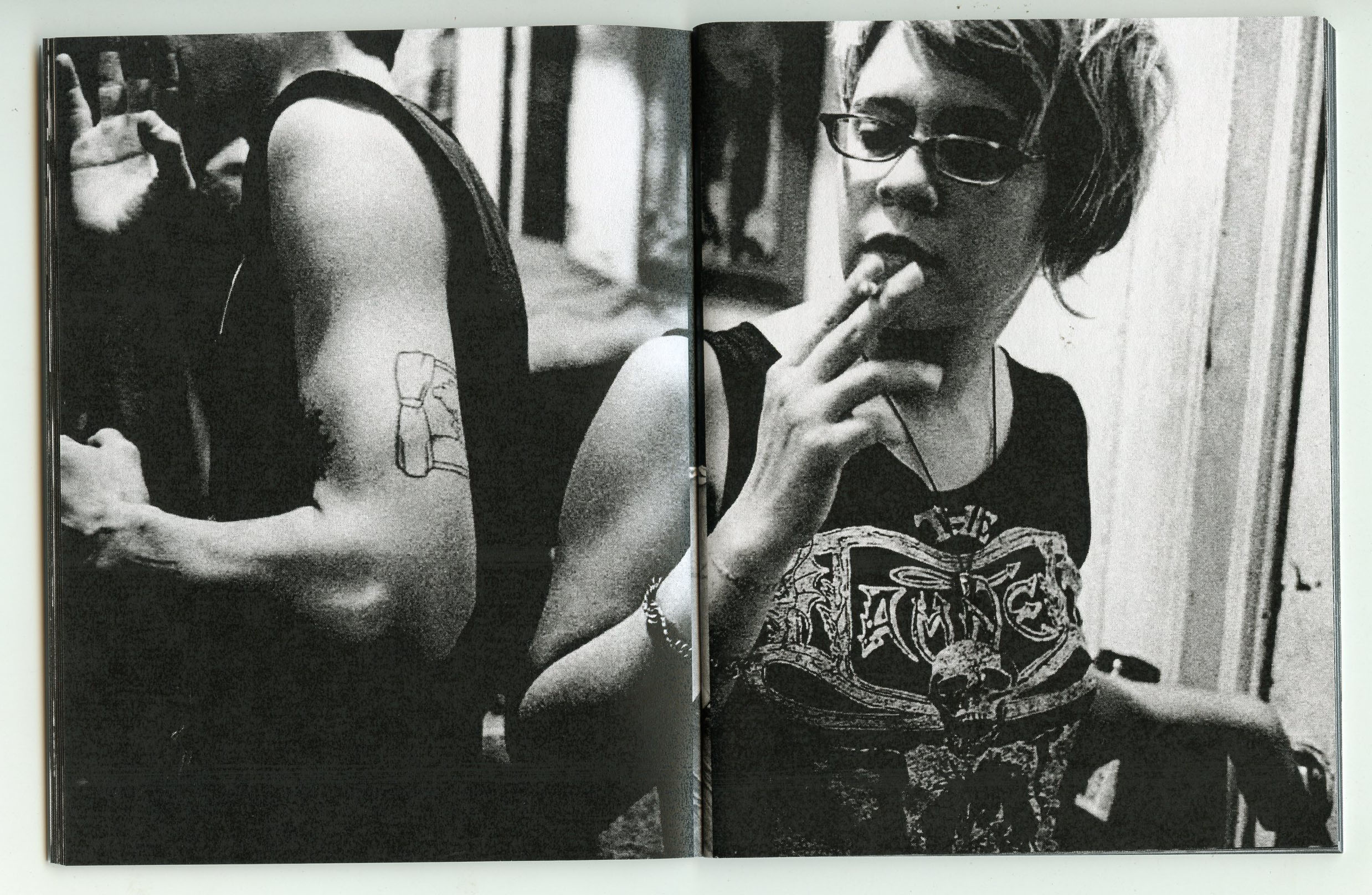

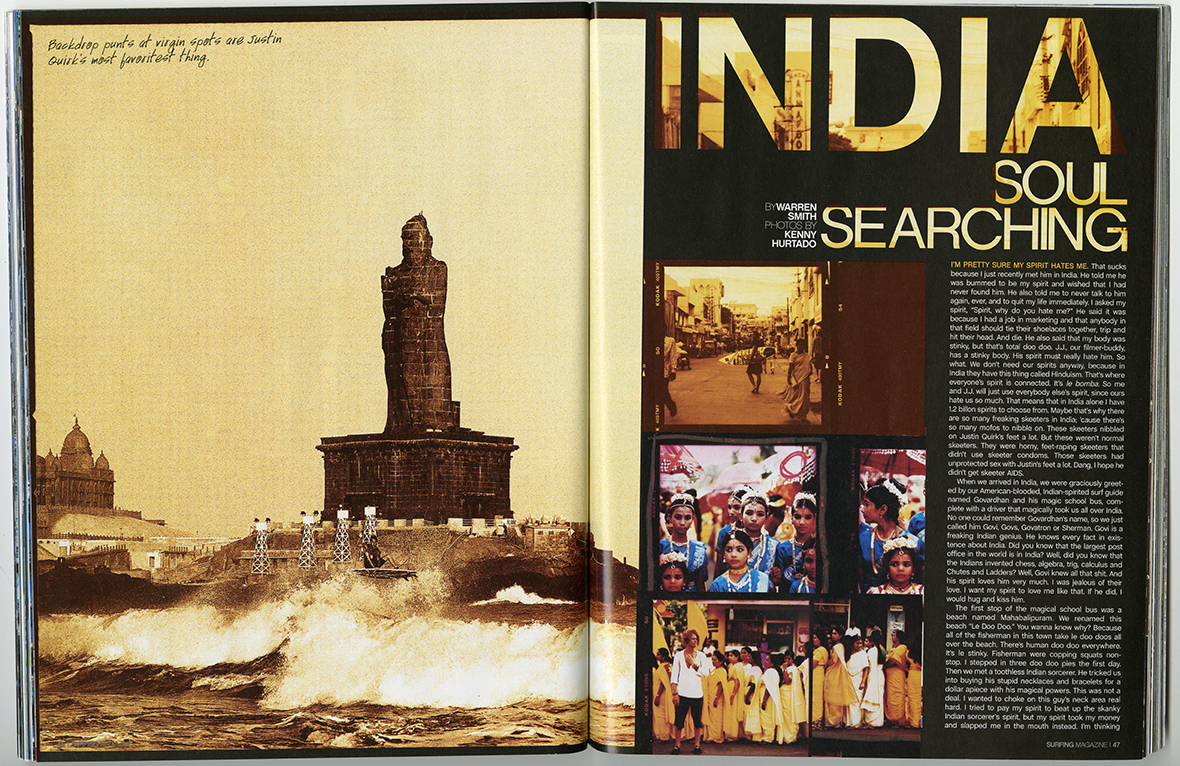

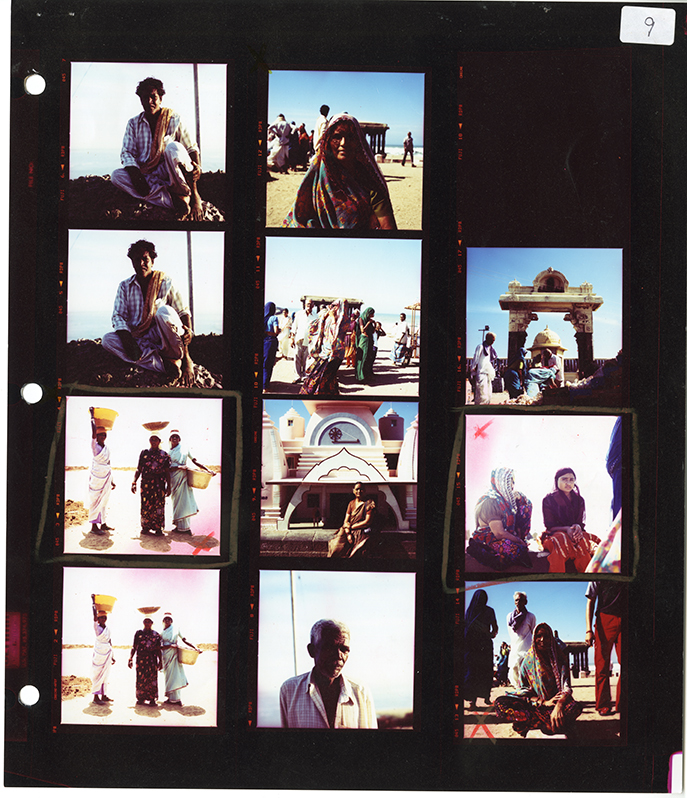

Another workshop (film & darkroom printing) was with Oliver Gagliani. I remember Oliver told me that when he was a guest instructor at the Ansel Adams Yosemite Workshops Ansel was photographing the landscape while Oliver was photographing the texture of the tents at Curry Village. For myself I enjoy photographing people in their natural environment.

From Bruce Barnbaum he would state that these three human ingredients will combine to produce success in any field of endeavor: Enthusiasm, Talent and Hard Work and that a person can be successful with only two of those attributes as long as one of two is ENTHUSIASM.

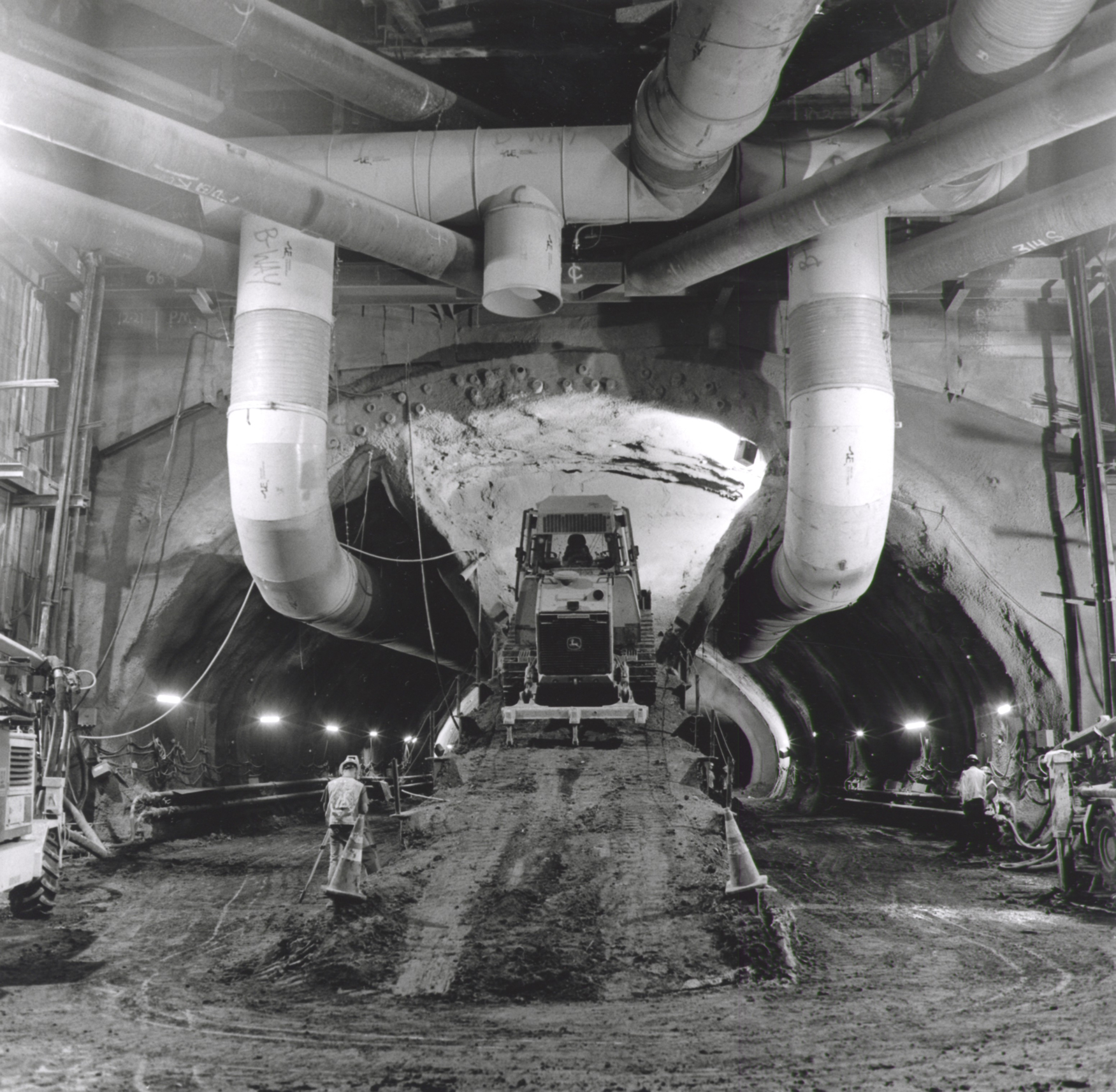

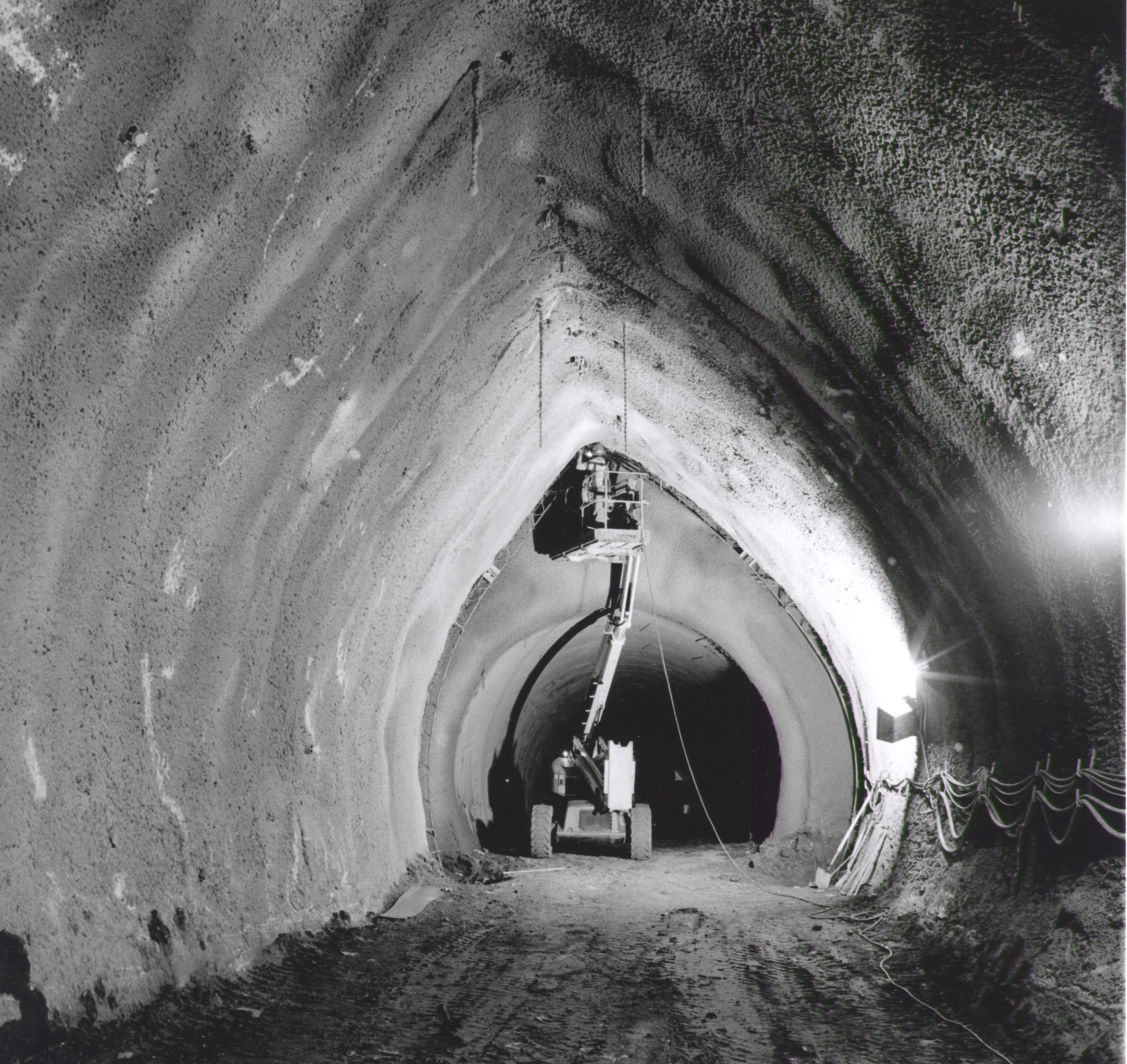

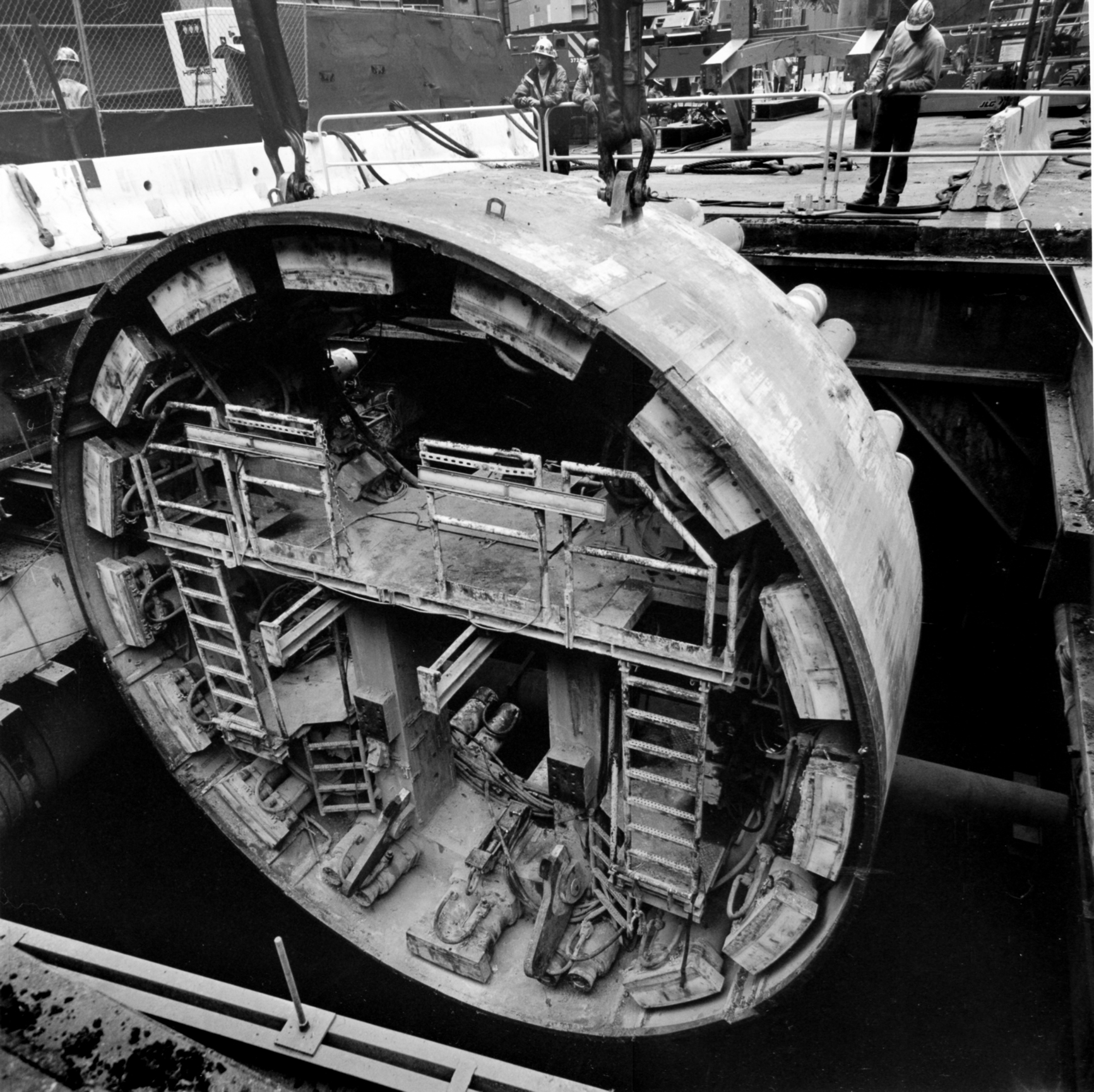

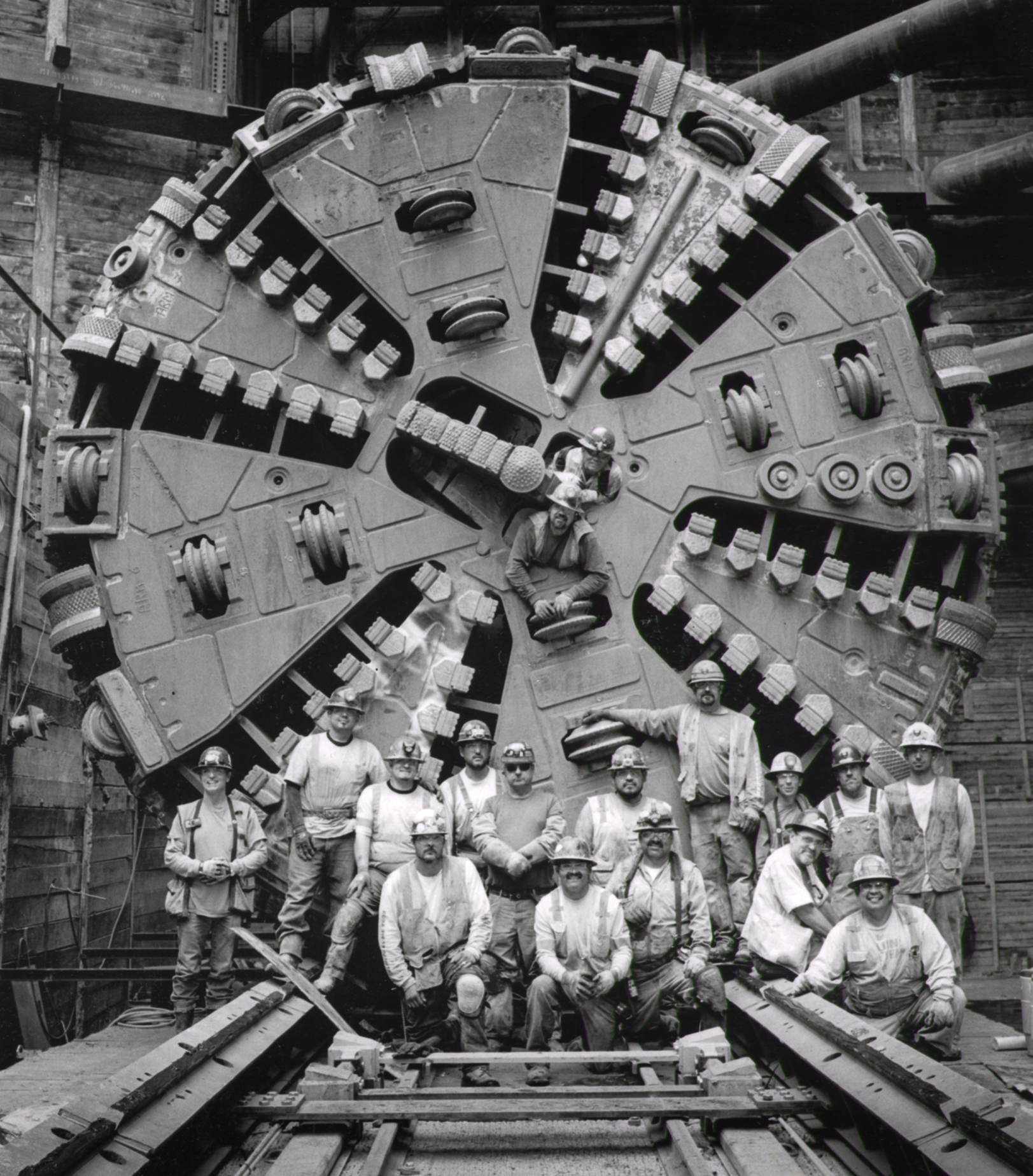

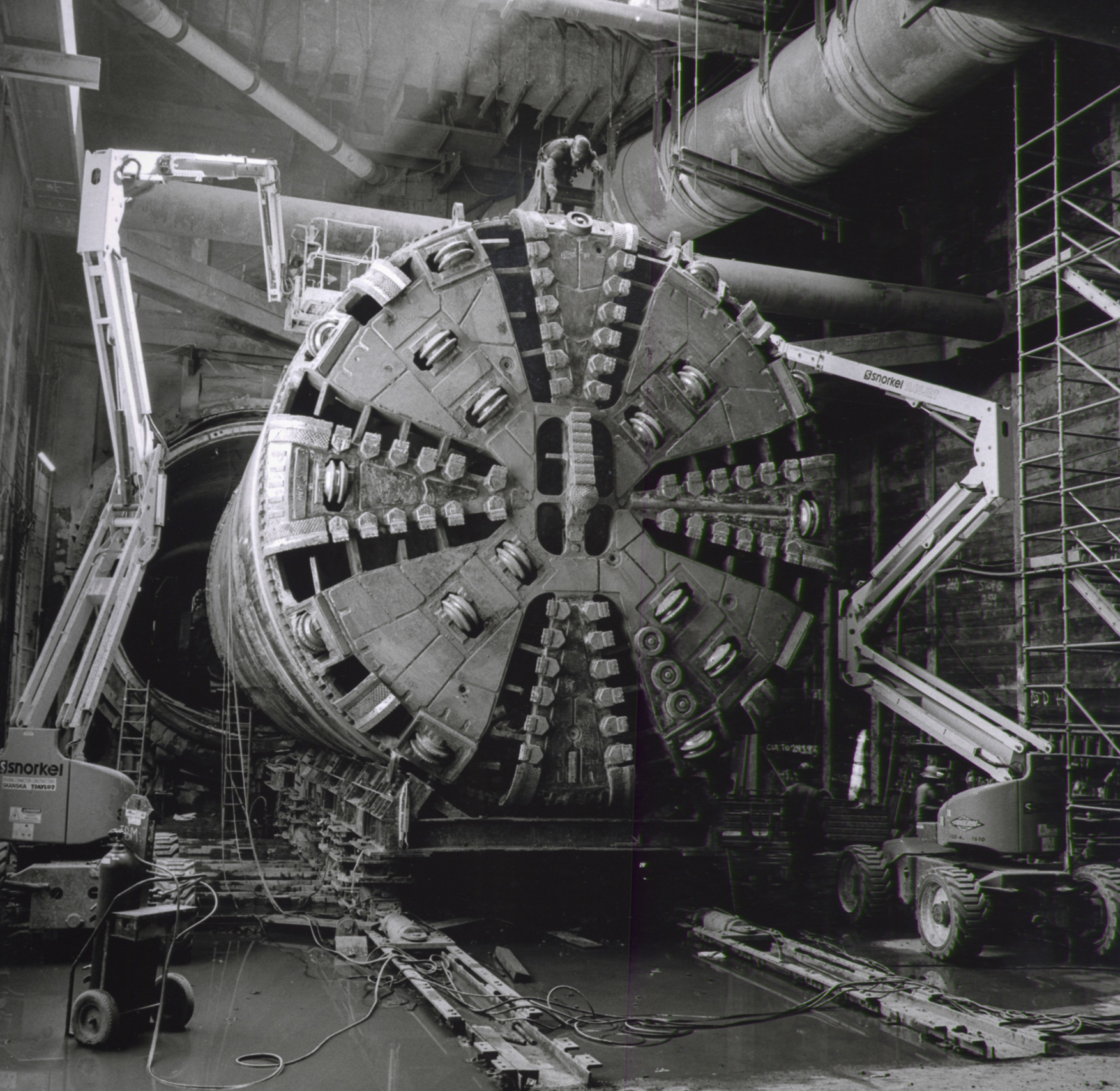

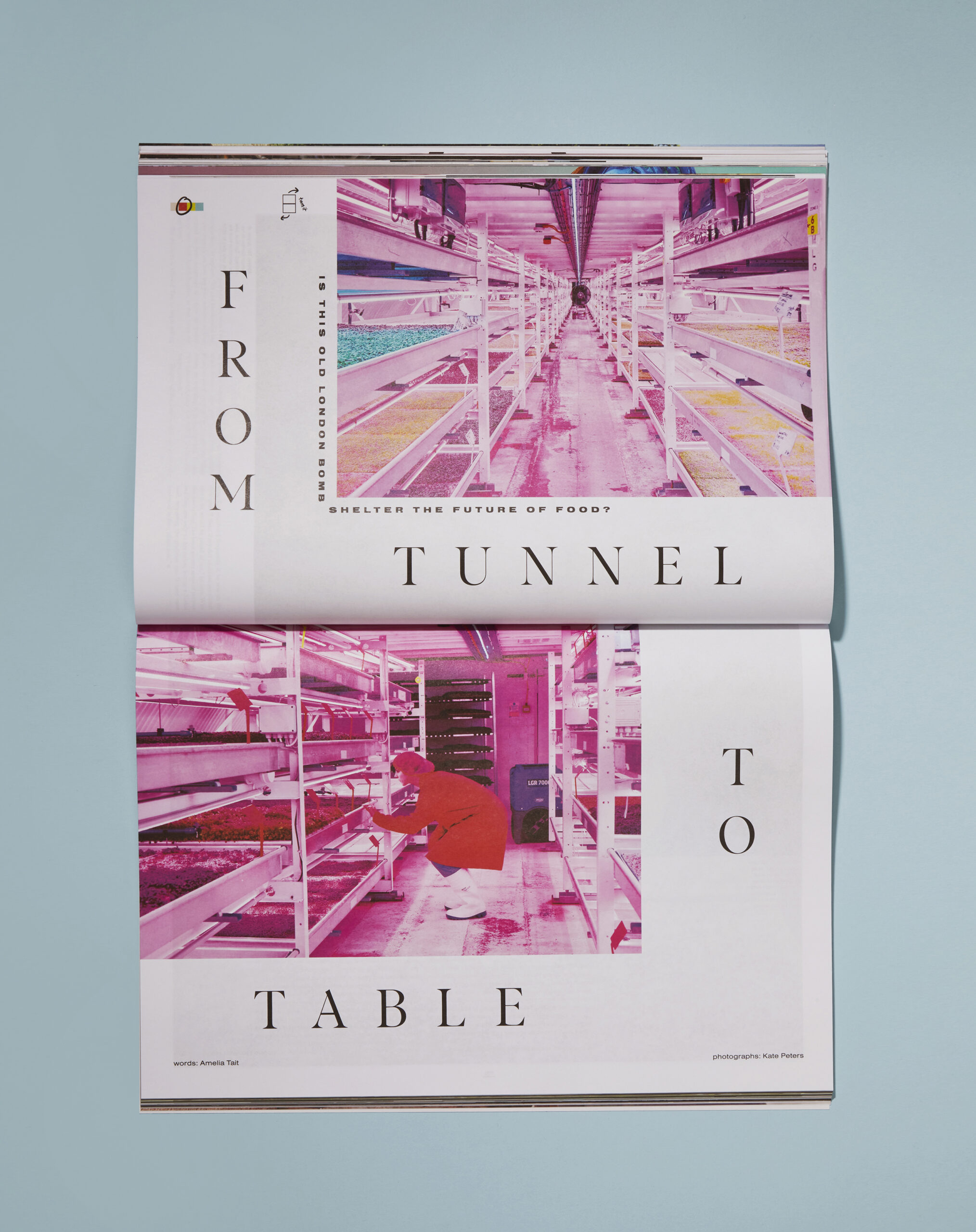

My personal photographic project has been photographing Los Angeles Underground Transportation and that has attributed to my Enthusiasm for this project and my love for Black and White film photography.

What was the focus of your photography workshop in Bishop and how did you come to photograph bridges?

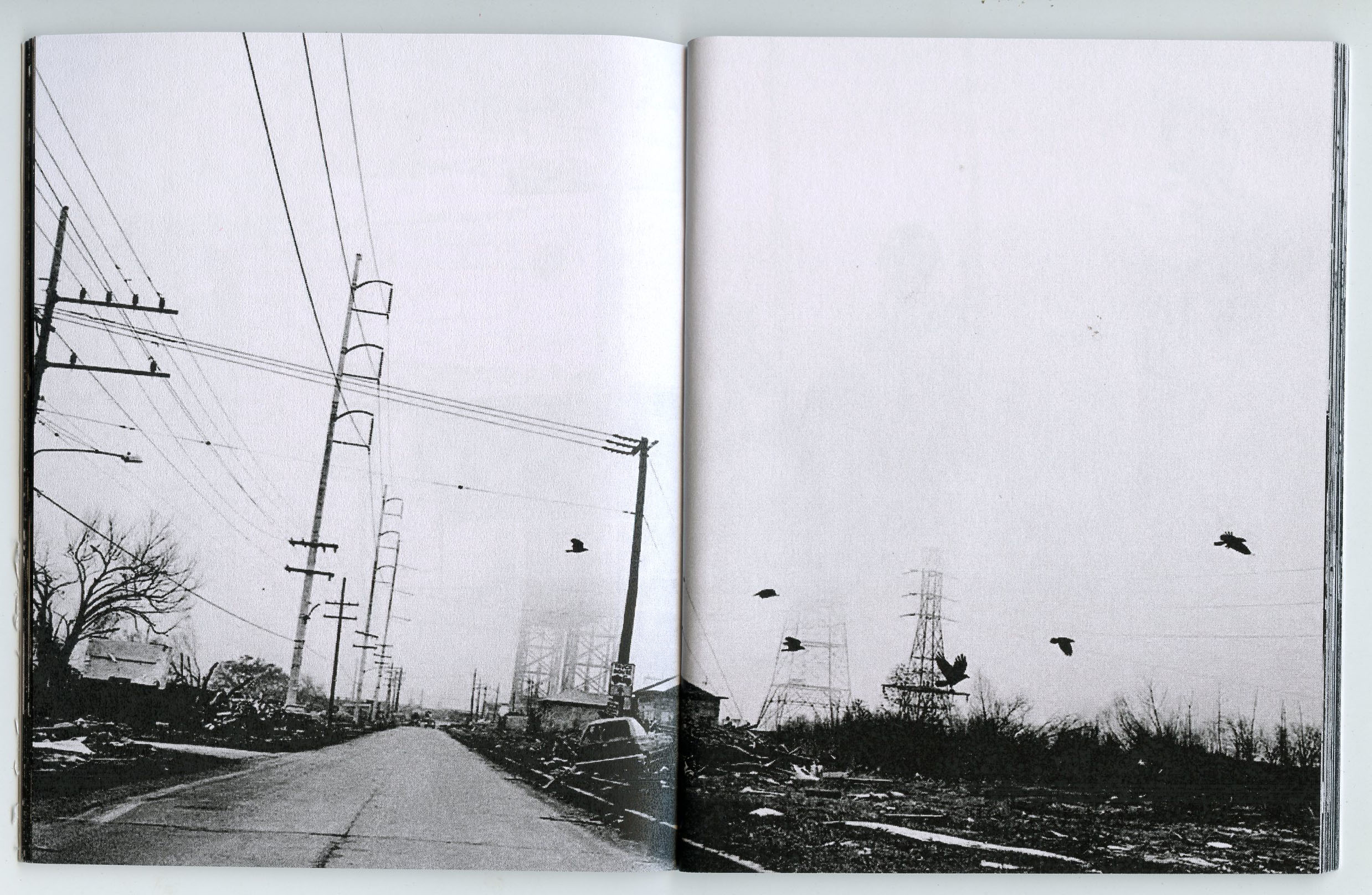

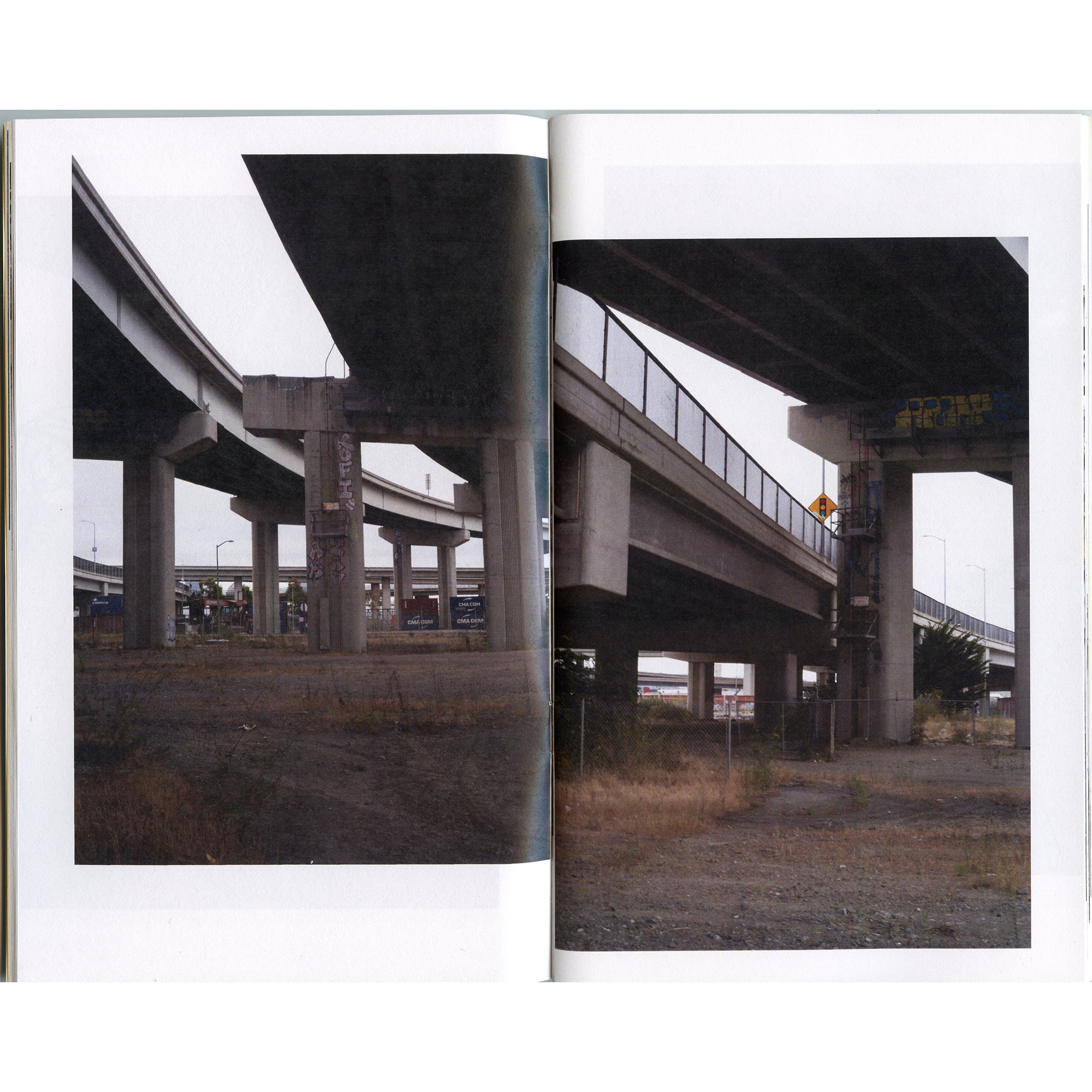

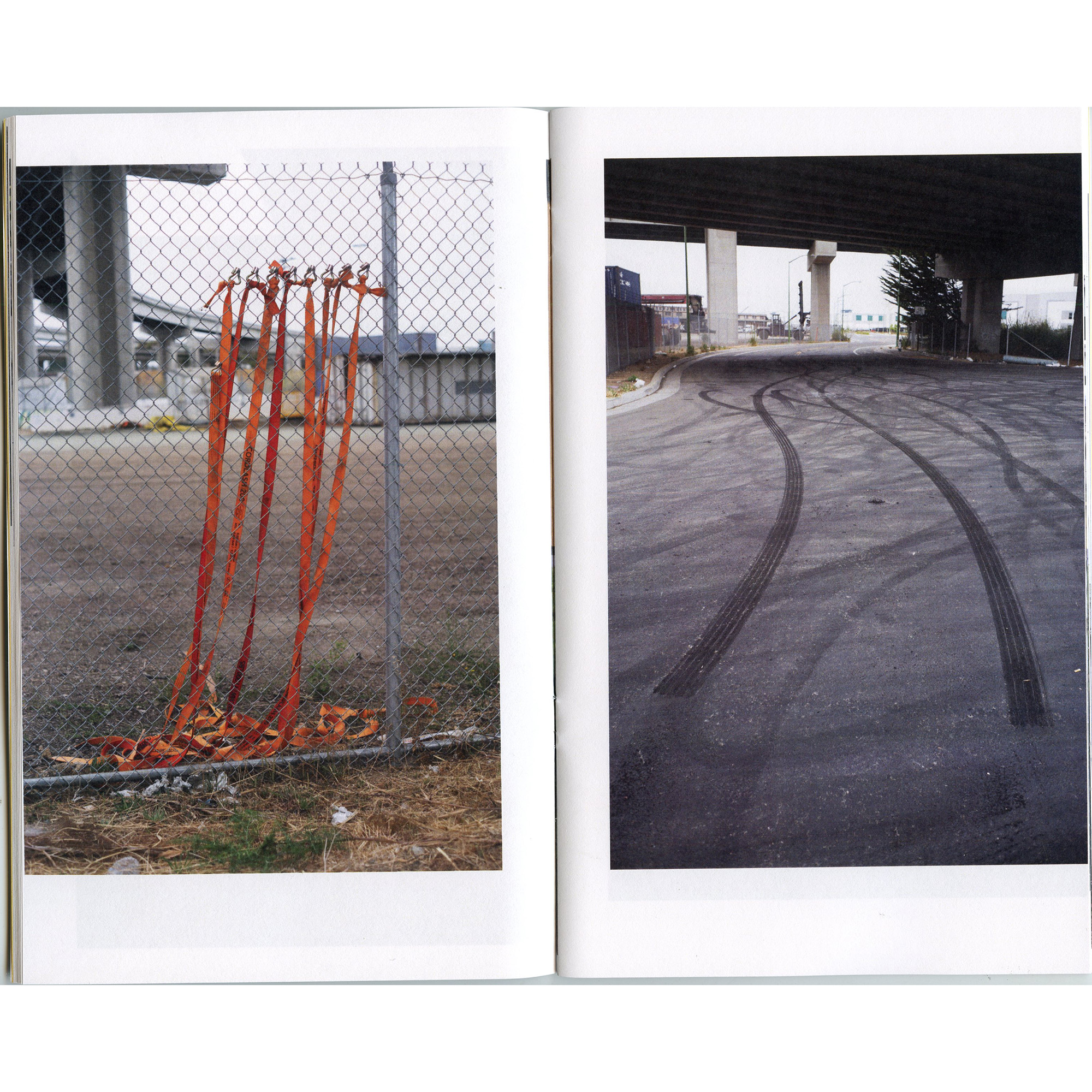

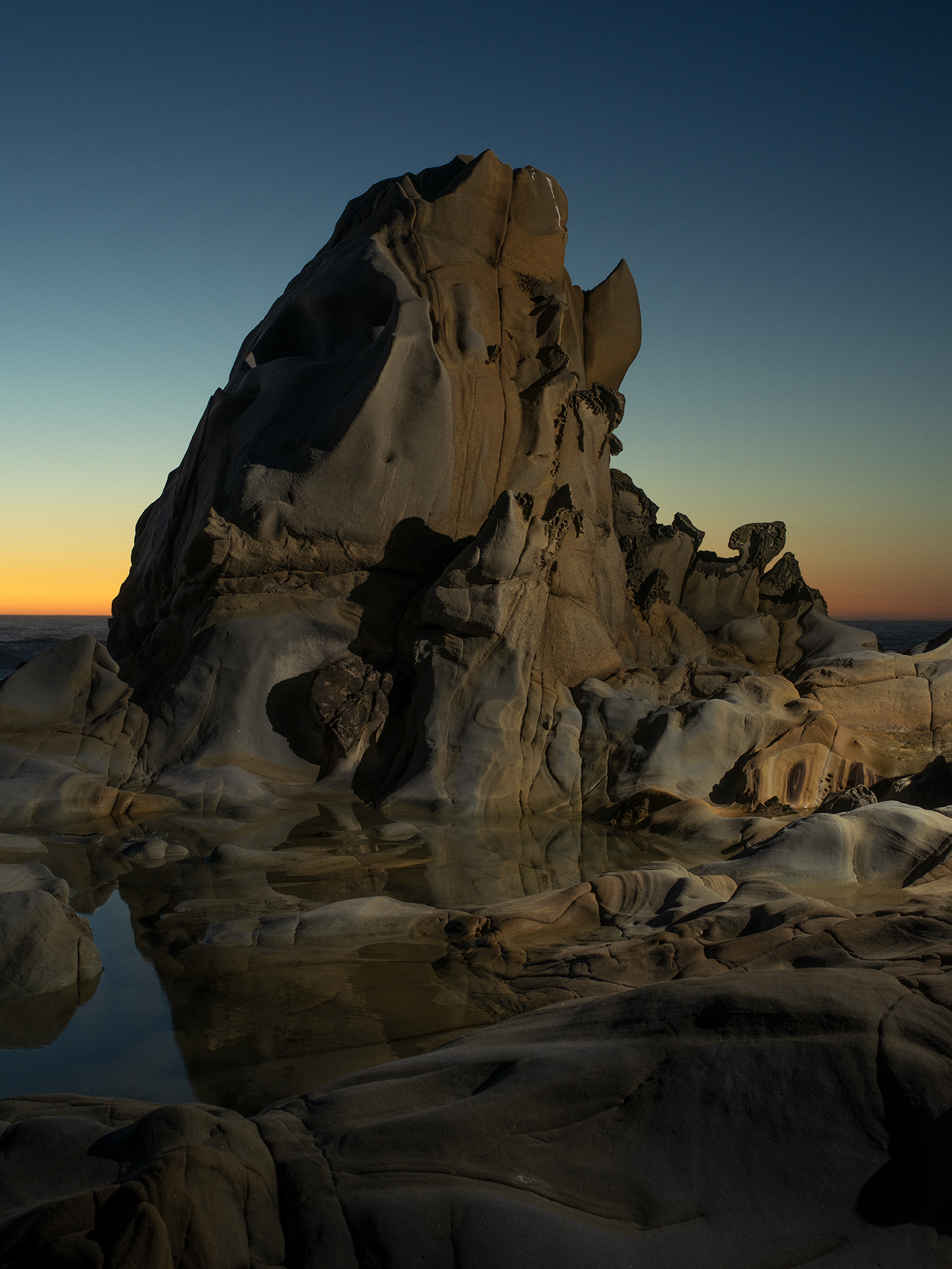

After taking the Owens Valley Workshop I became good friends with photographer Ray McSavaney since he lived in Los Angeles and would do a workshop called Urban Los Angeles where on Friday evening we would meet at his studio and meet the workshop participants and bring some prints to share with the group. On Saturday and Sunday we would then photograph in Los Angeles. Some of those locations would be Victorian Square, under the bridges of the Los Angeles river, Bradbury Building, etc. For myself the first time photographing under the bridges or freeways was this does not look interesting with all the concrete but when I went home and developed my B&W film the concrete had a glow to it with light underneath.

How did your Underground Subway series begin?

While driving to work everyday on Hollywood Blvd I saw a carwash go out of business and thought that was strange especially with all the cars in Los Angeles. Then saw construction fences going up with a sign saying this is a Federal Funded Transportation Project that included Los Angels County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. I then wrote to the MTA Arts about obtaining permission to photograph. One year later I heard back and they told me I could come for a day and that day turned into over three decades of photographing LA Metro Underground Transportation Projects.

Why was the Huntington Library interested in collecting his work and what was your role in all of this?

I had contacted the Huntington Library about showing them my portfolio from my Underground Subway series and met with Jennifer Watts (Huntington Library Curator of Photography) where some of my artwork is now collected. I mentioned to Jennifer about looking at Ray McSavaney’s photography and then the Huntington Library started collecting some of Ray’s photographs. Ray passed away the week after I retired in 2014 and John Sexton asked me to help with Ray’s estate where now with help Ray’s artwork, is collected at Huntington Library, Center for Creative Photography, Portland Art Museum, Los Angeles Central Library and University of Utah Marriott Library. Explorations is Ray’s book that he self published and is available here.

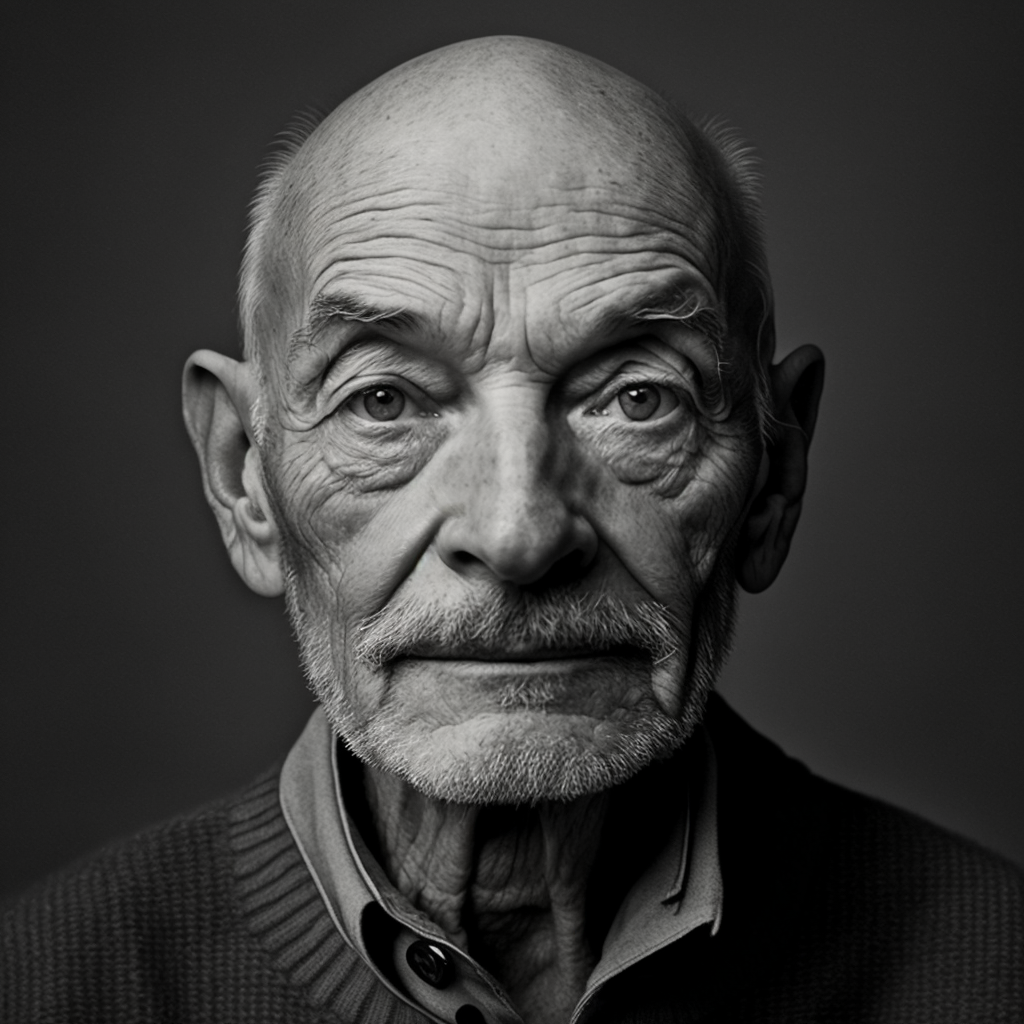

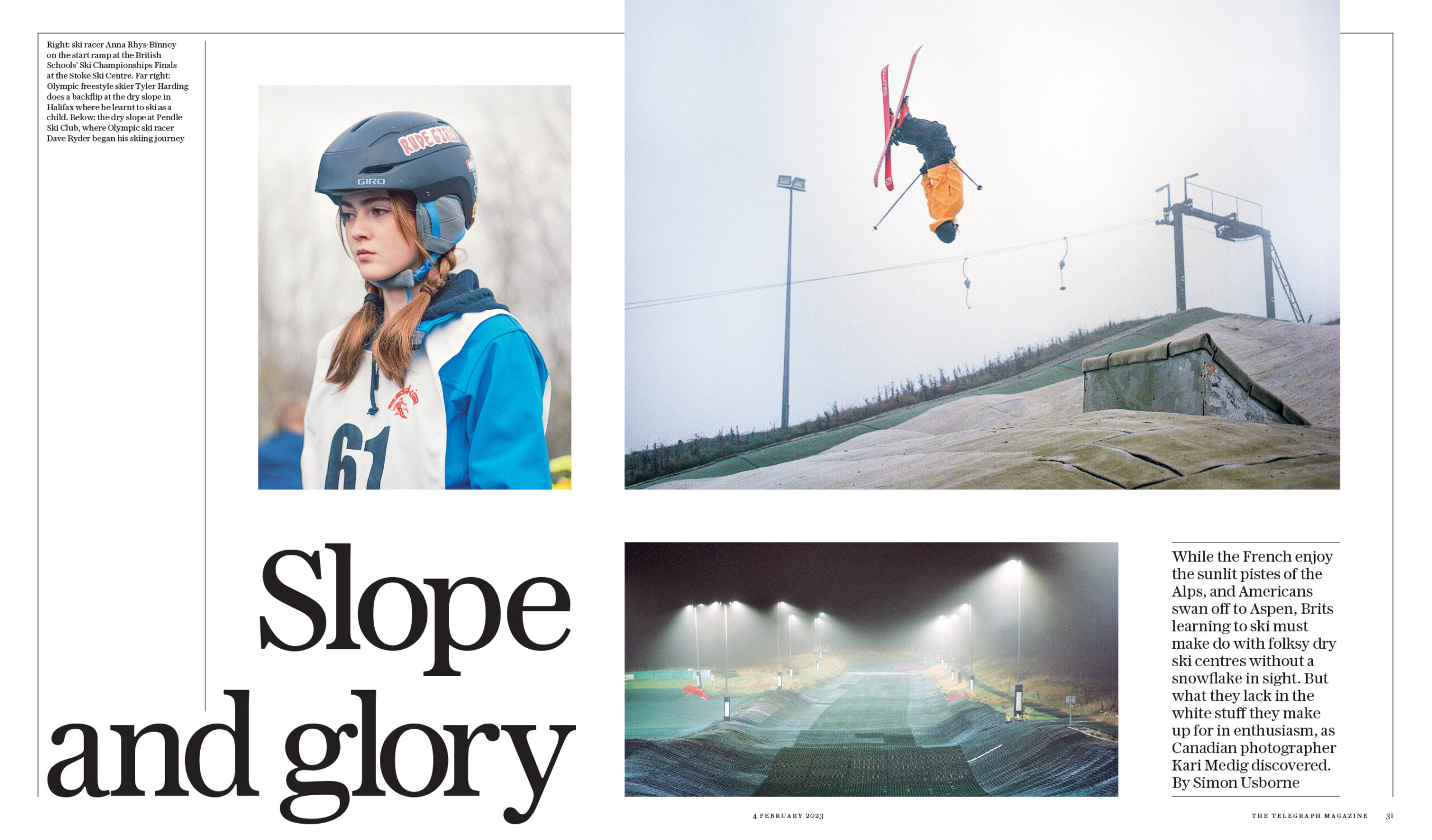

Ray McSavaney

What would you tell your younger self?

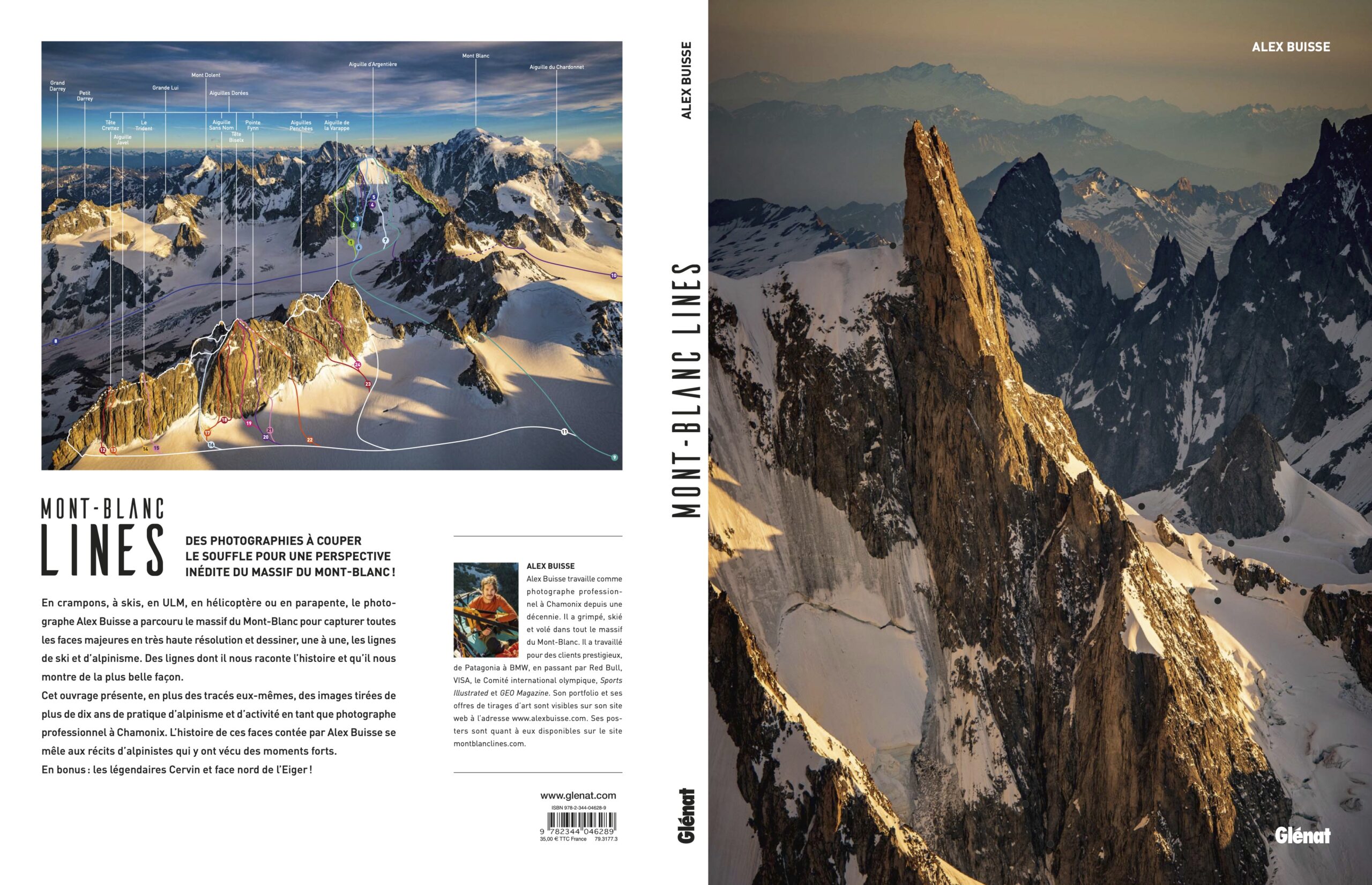

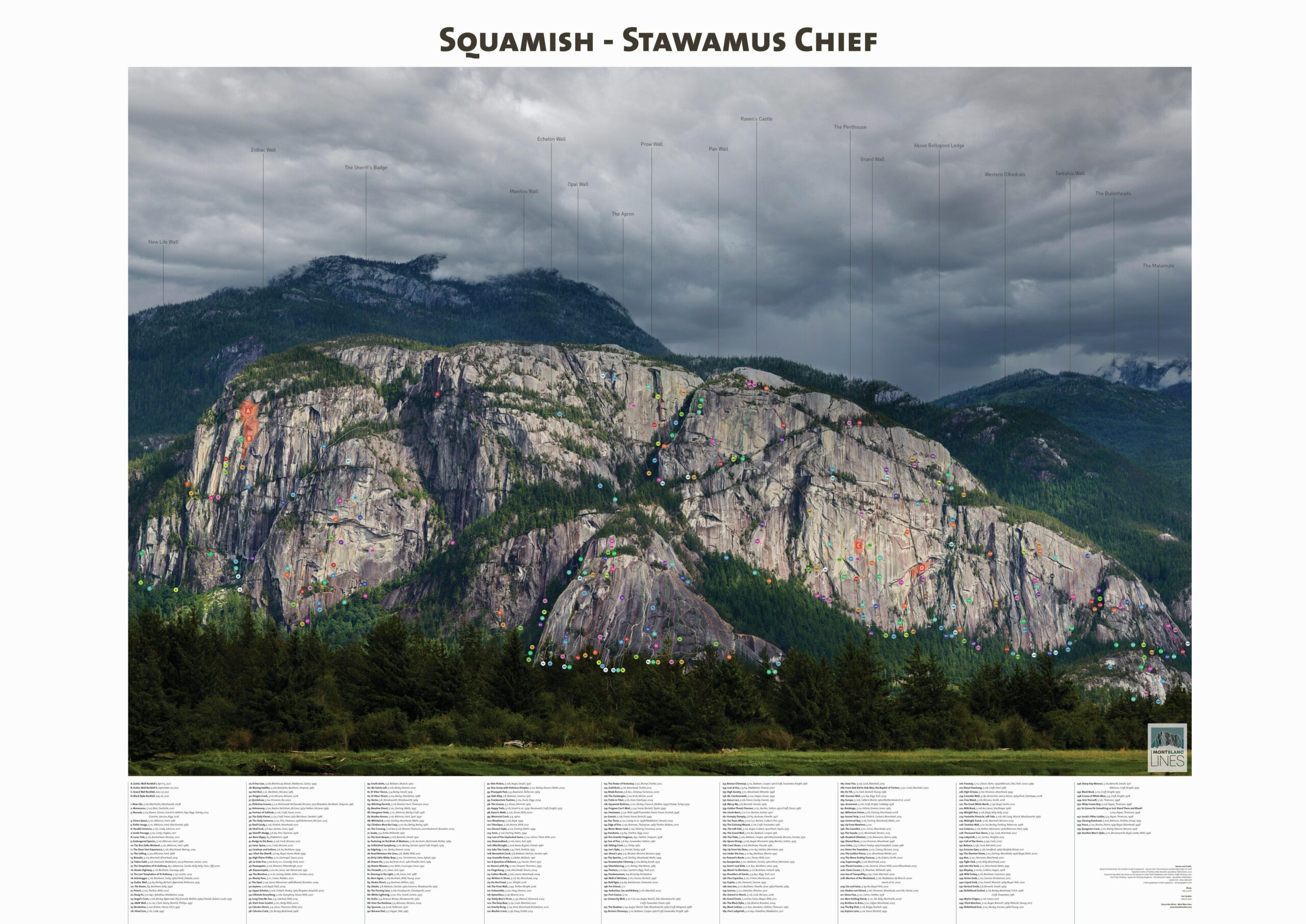

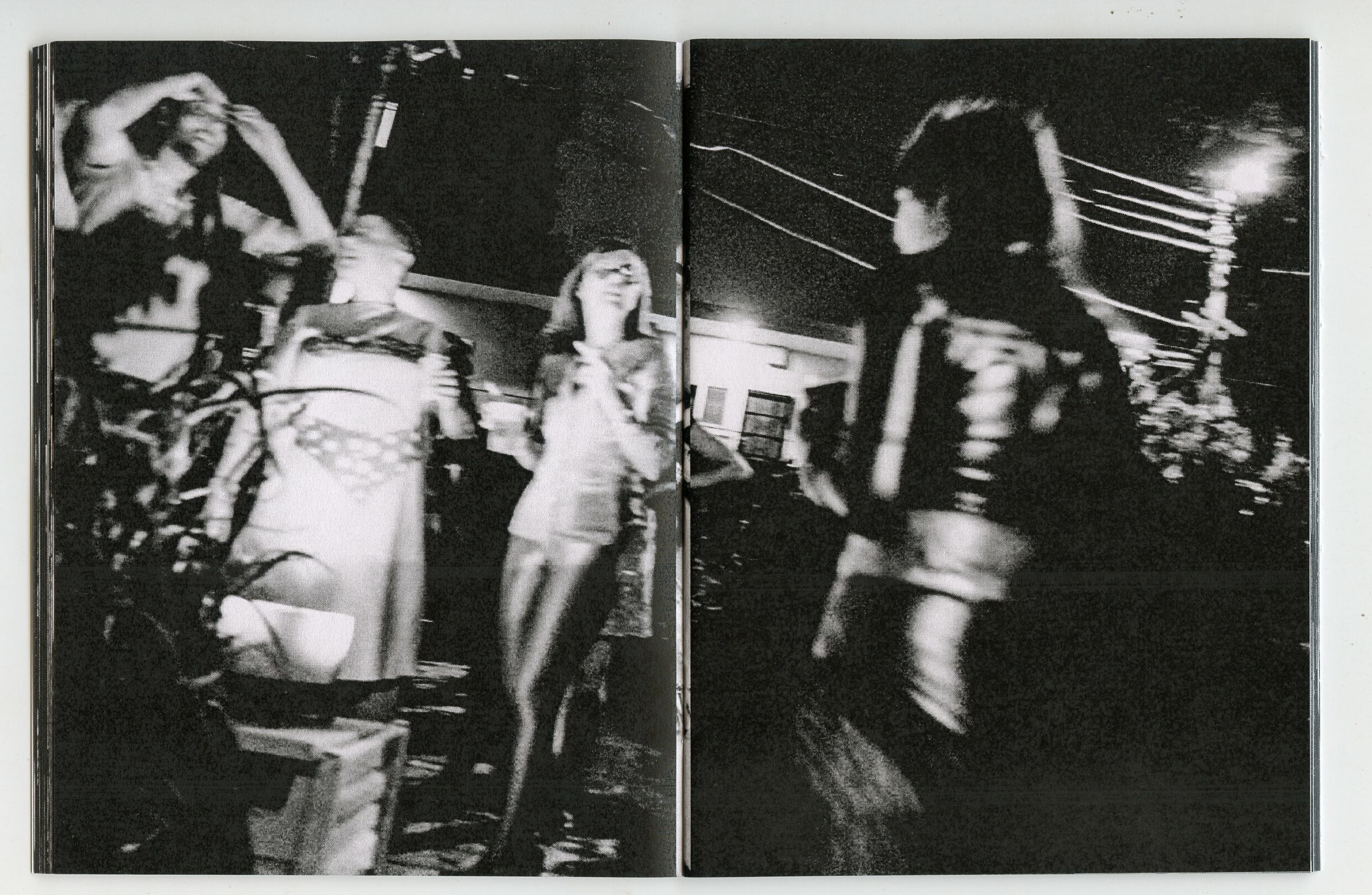

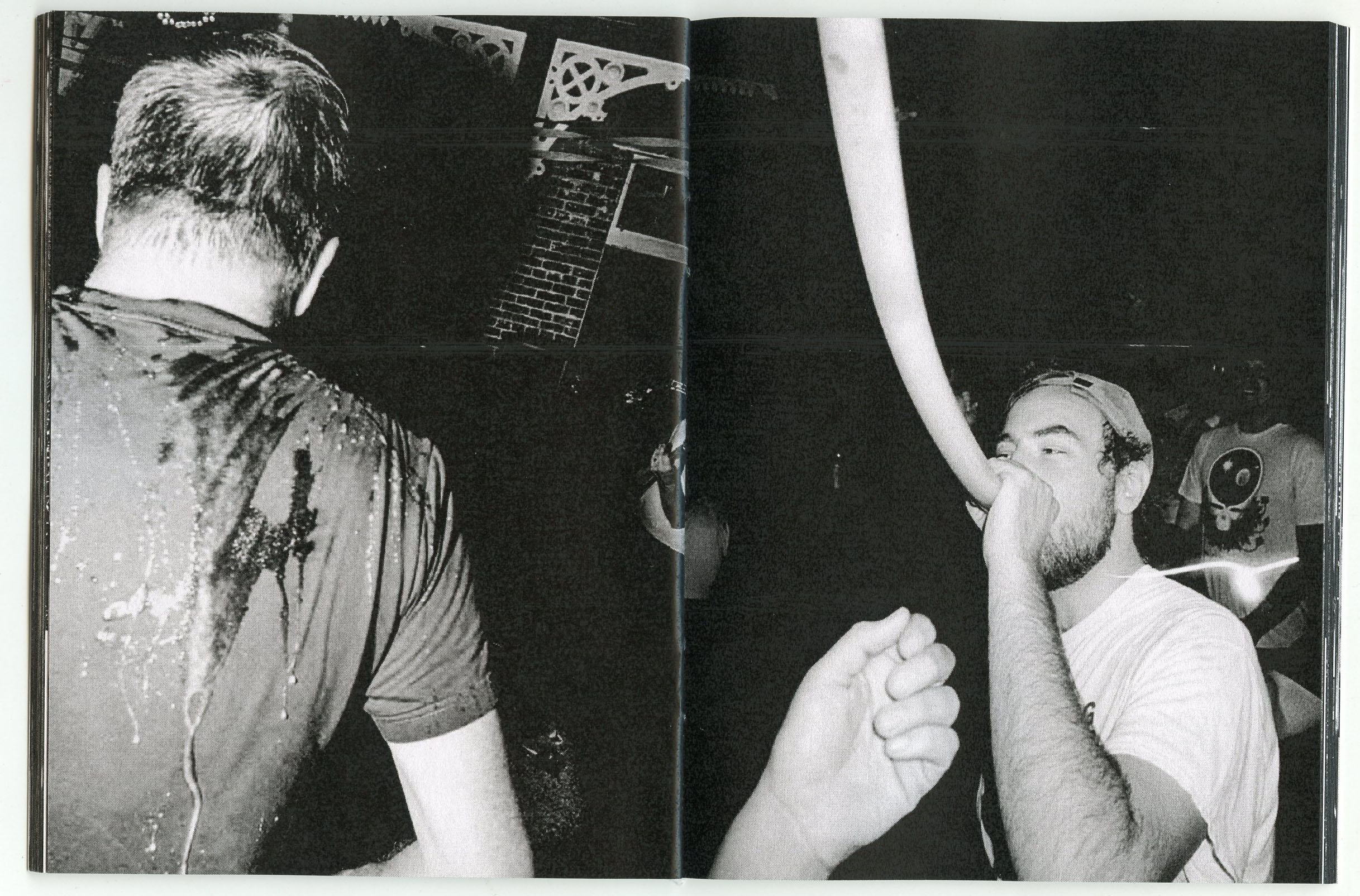

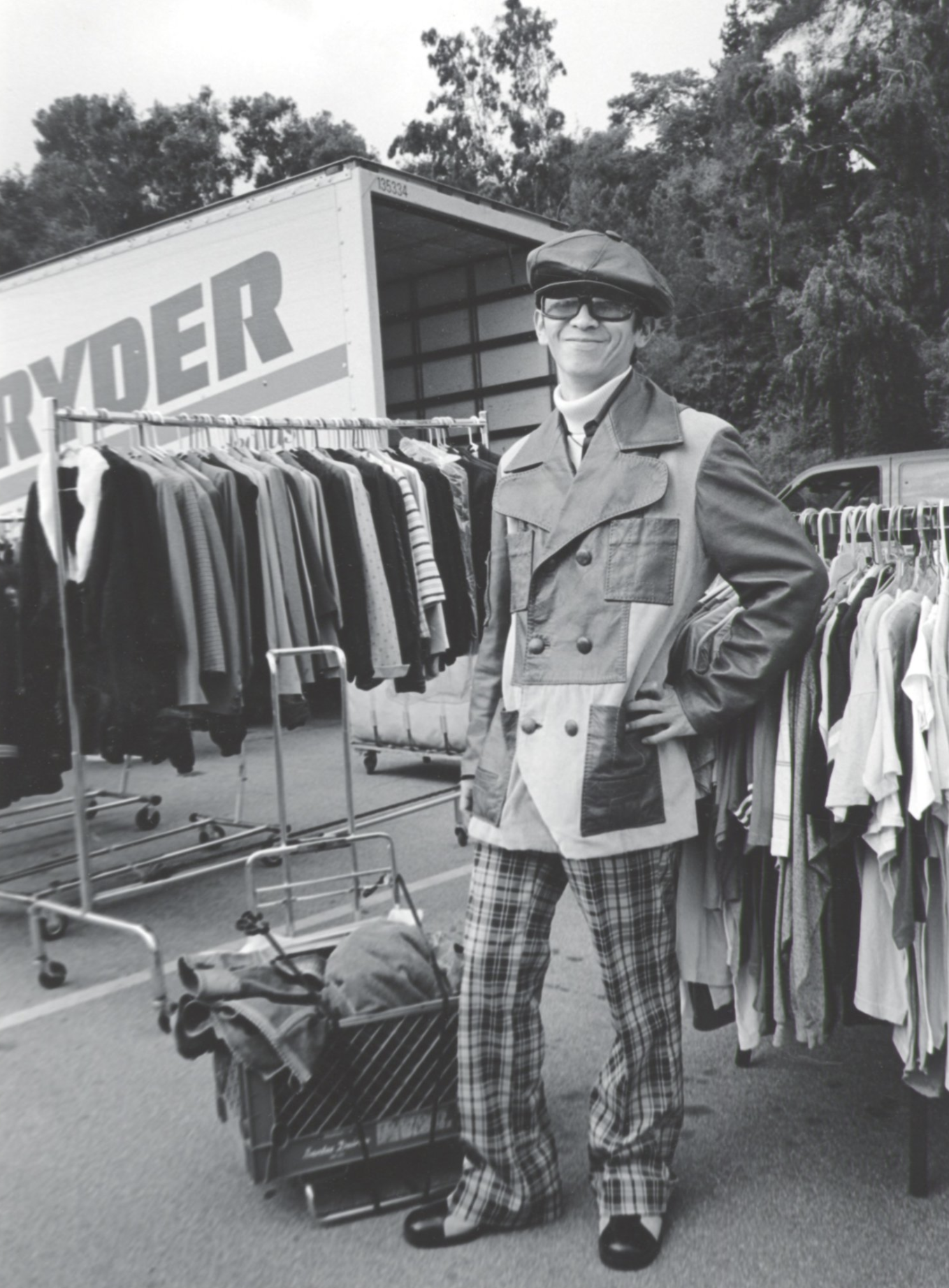

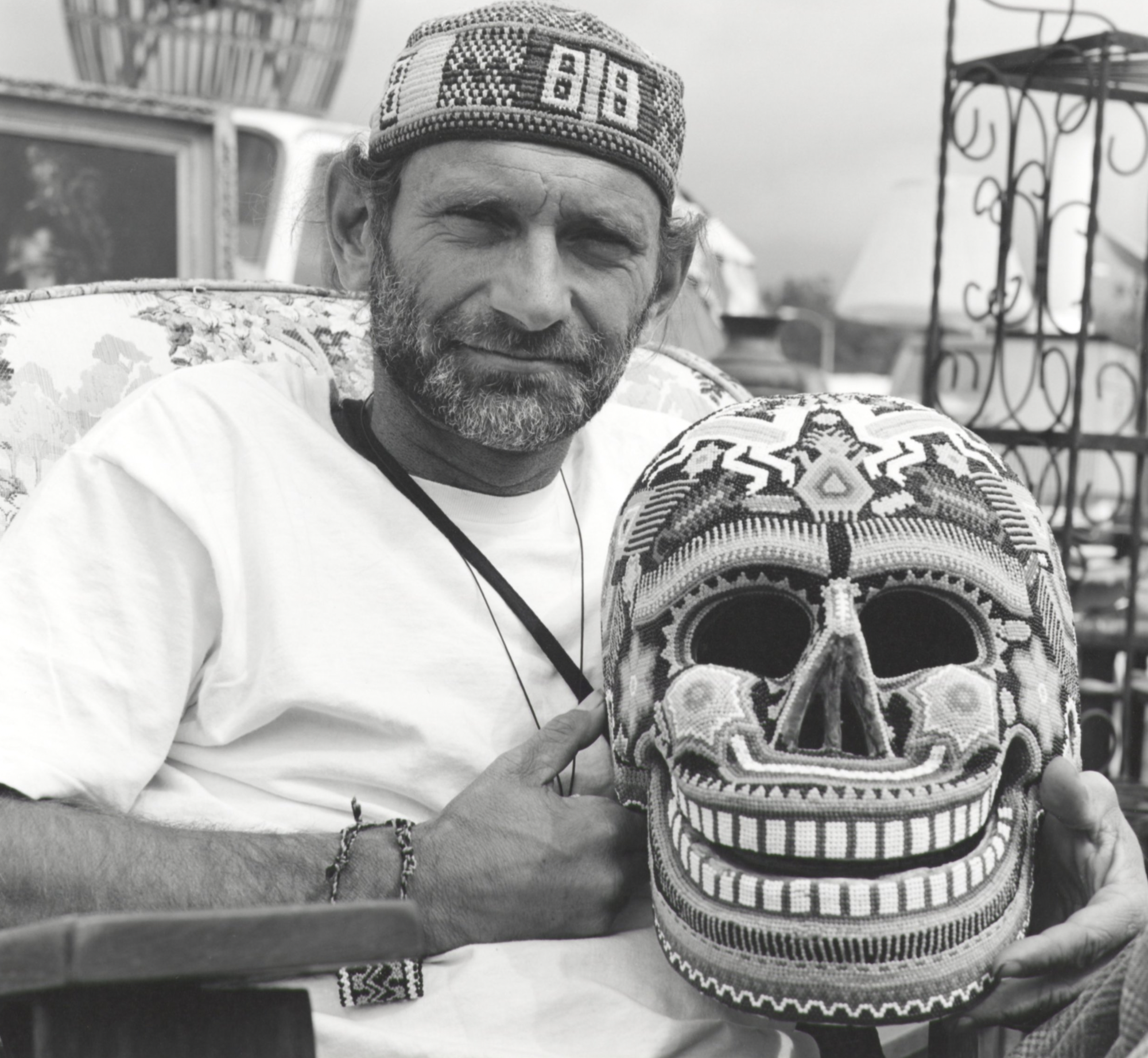

I would probably try to keep up with the digital world taking more classes to better my skills in Photoshop, Lightroom and designing a website. I wish I did more oral interviews with my subject matter. Now I look forward to publishing a book on my different construction projects that also includes the the rebuilding of the iconic 6th St Viaduct. I do have some older projects where I photographed the vendors and buyers at the Pasadena Rose Bowl Flea Market and Harley Davidson Riders.

What are you currently working on?

I’m currently photographing the Underground Construction along Wilshire Blvd where Metro plans to build seven new Subway Stations by the Summer Olympics in 2028