The best art connects to something universal. (That’s why it’s the best.) It has a quality that speaks to people across our many divides.

Michelangelo’s “Pieta,” or a Van Gogh olive grove, can inspire almost anyone. Even better, look at Jackson Pollock’s seminal paintings, which attempted to represent Jung’s collective unconscious, and many believe they do. (Myself included.)

Pollock’s work doesn’t look so great in reproductions, because the scale, texture, and color patterns all need to be experienced in the flesh.

Sometimes, size matters.

(But that’s not the point I’m trying to make.)

There are universal aspects to humanity.

We love. We hate. We eat. We die.

We sleep, and dream.

We work, and aspire.

Some parts of humanity are the same, no matter when or where you live. (Even Neanderthals would have hoped for a cave with better-tasting-water, I’m sure.)

It is easier, I’d say, to focus on where we differ. Each tribe concerned with its own, excluding others. My history is not your history, and you can’t take mine, if it’s not yours.

In general, I’m open to critiques of cultural appropriation, when appropriate. In light of where things ended up, Marvel definitely should have cast an Asian actor as the lead in “Iron Fist.” (Opportunity missed.)

But where to draw these lines can be murky. How much sampling is OK? What belongs to all of us?

I bring this up in light of the Dana Schutz controversy. Her painting, in the Whitney Biennial, has drawn countless words because she based it on a disturbing image of a dead Emmett Till, a young boy tragically murdered during the Civil Rights Era.

The work was threatened with boycott by certain African-American artists, who wanted it removed, or even destroyed, to prevent her from profiting off the collective pain of their culture.

My colleague Maurice Berger, writing in the Lens Blog, sided with those who thought this use of appropriation uncouth. Calvin Tomkins, in The New Yorker, had a long piece on the artist, including up-to-the-minute details of the controversy, and her responses were exactly what I predicted.

When you try to look for that spark of the universal, you think in terms of the collective. Emmett Till’s story, and the Civil Rights era, are American stories. They happened here. If you’re born and raised in the US, our country’s legacy is yours too.

We hear a lot about white guilt, but not so much white shame. When you’ve been taught, for most of your life, that your country has done awful things in your name, you develop a certain cynicism. A willingness to explore the edges of things.

Furthermore, we were encouraged, in art school, that it was best to keep your mind open to all ideas. (Ms. Schutz and I went to NYC Graduate Art schools around the same time.) We were pushed to explore creativity, and then judge its aftermath once the work was done. Is it good, bad, brilliant, offensive, un-showable, ridiculous?

That’s what I thought she’d say, Ms. Schultz, and it’s exactly what she said.

She explored the ideas, knowing they were risky. She made her painting, based upon a symbol of hatred from America’s past. If you look on Google Images, you can see the style is consistent with her other work.

Censorship denies people the right to even make up their own minds about whether something is worthy of their consideration. Provocative work makes people think and talk, which is part of its point.

When things are made public, and put on display, we all get to decide whether something meets our moral standard or not. And with respect to publicity, those who sought to minimize the painting’s impact inadvertently fanned the flames of dialogue.

I’m fascinated, and I haven’t even seen the painting in the flesh yet.

But I do believe artists have a right engage with any culture or idea they want, and then see what happens. (Just because you’ve made it doesn’t mean you have to show it). And as one who has taught in minority communities for nearly 12 years, I can affirm that cross-cultural communication is a good thing.

I’m on the subject today, having just put down “Rex,” a new book by Zackary Canepari, recently published by Contrasto books in Italy. I was anxious to get my hand on this one, as I first saw the project in Critical Mass in 2015, and fell in love.

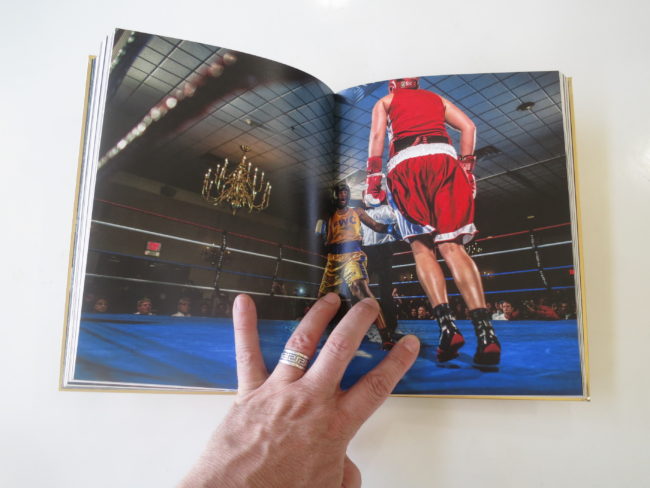

It has since garnered much acclaim, as the story of a young, female boxer in Flint, Michigan spawned a movie, an interactive website, a book, and presumably print exhibitions as well. This thing thing spun off content like Disney around a new Marvel franchise.

(Dr. Strange! Not as funny as Tony Stark, but he has magic!)

The documentary film, “Rex,” was a hit, and even received a Guggenheim Fellowship this week. Big ups to Mr. Canepari, I’d suggest.

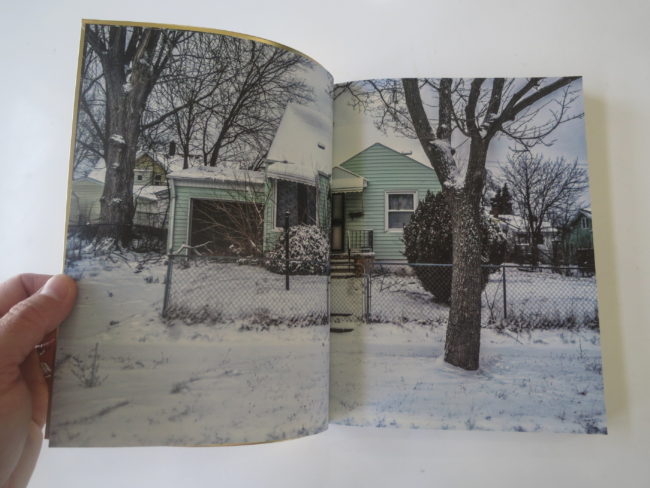

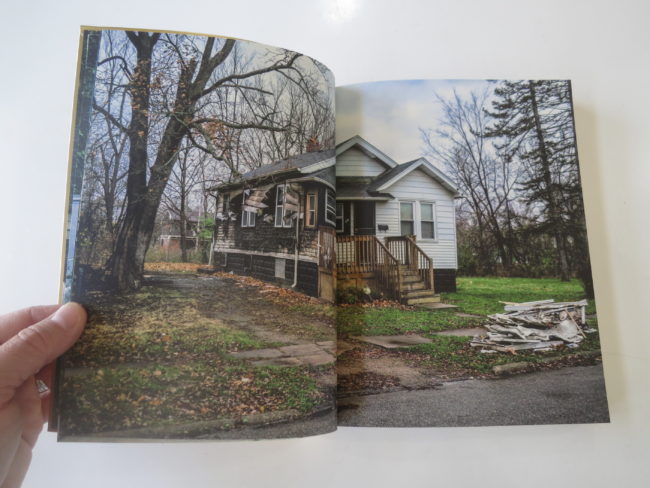

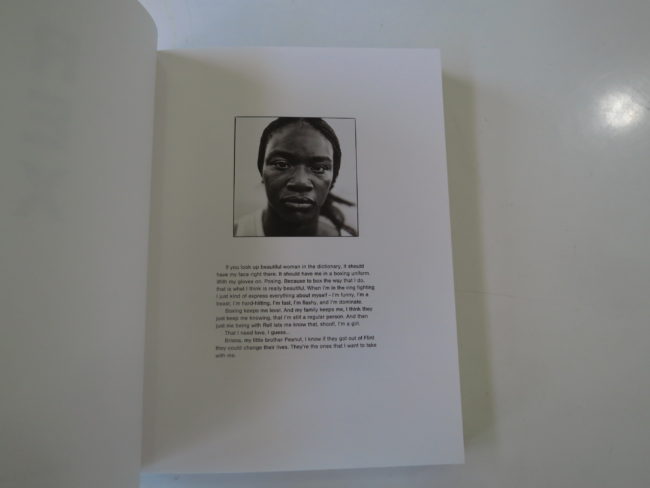

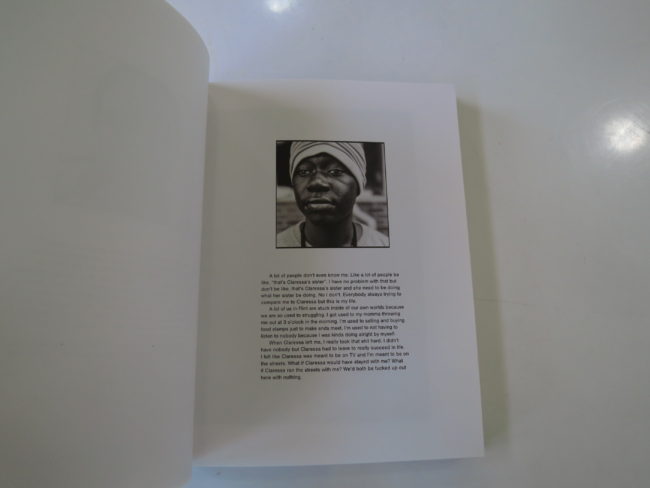

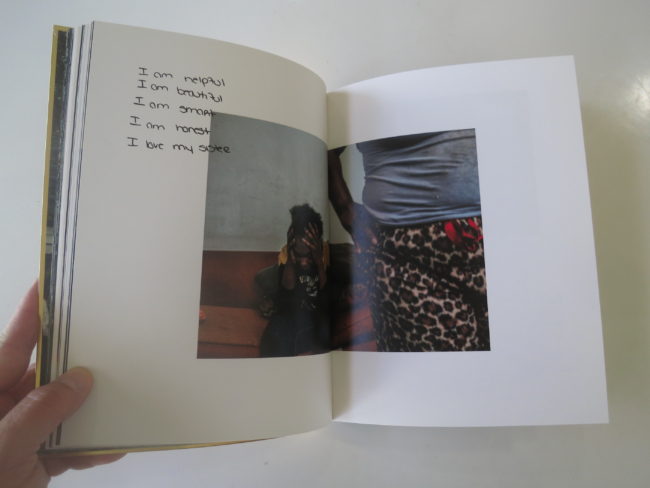

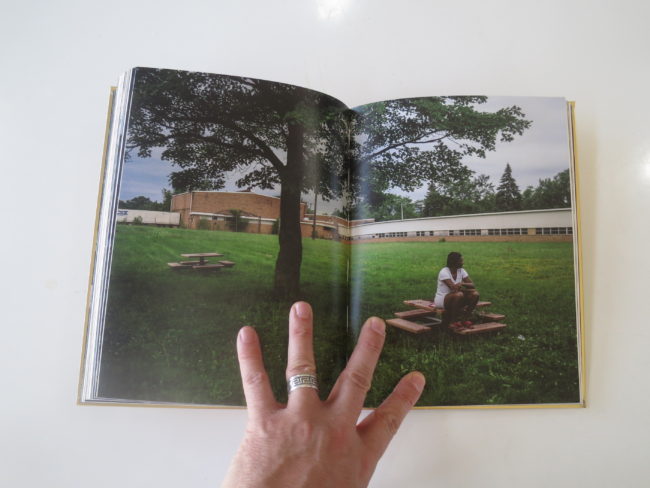

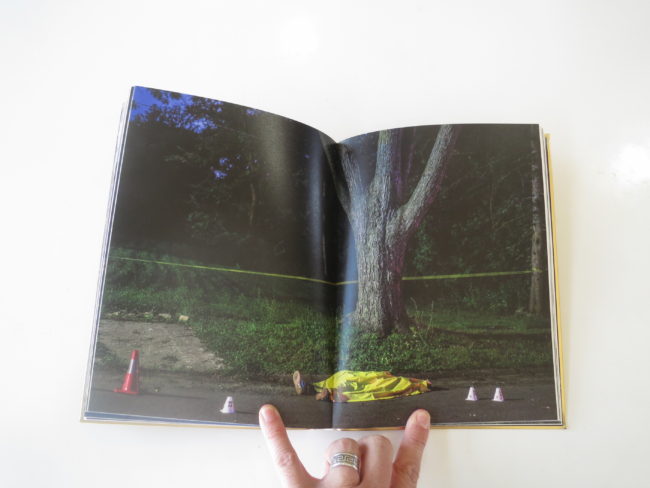

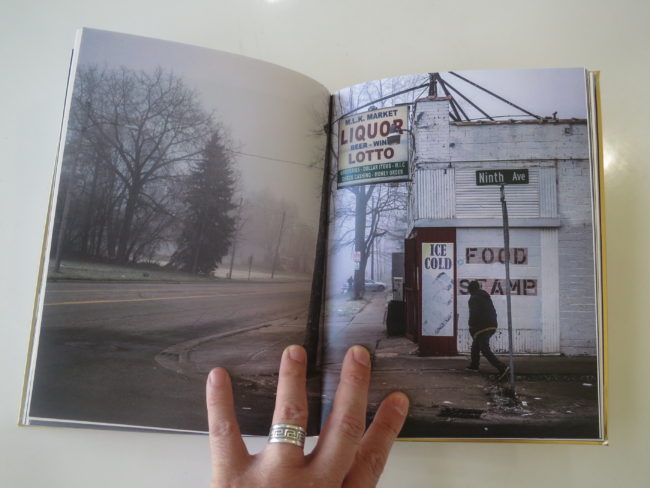

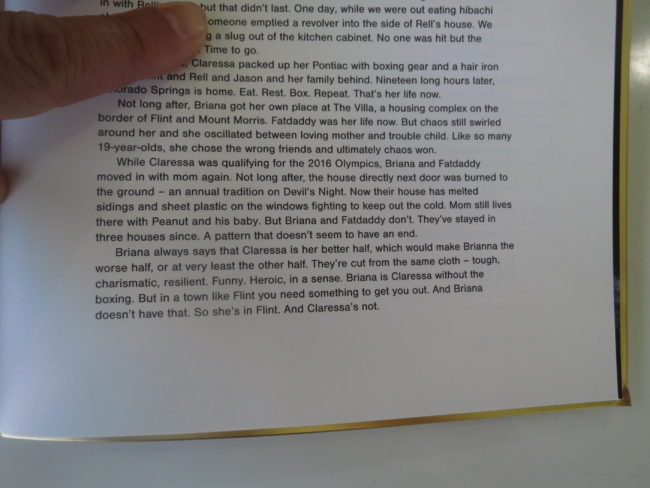

I like the book, and thought the gold cover was a terrific touch, as it alludes to the gold medal at the metaphorical heart of the story. Claressa and Briana are two sisters, living in the same water-poisoned town, living lives on separate trajectories.

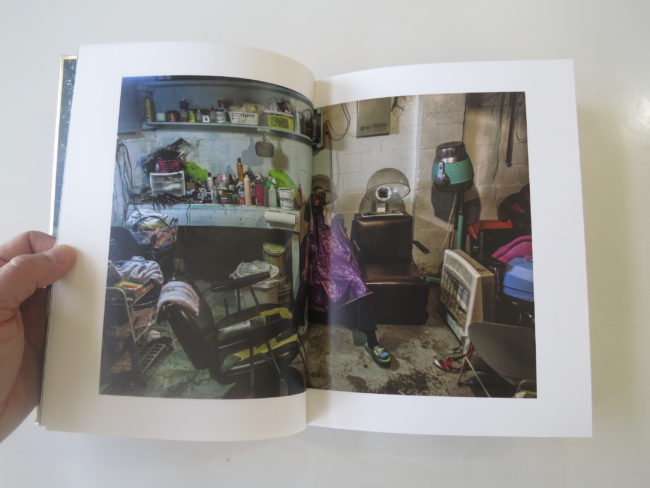

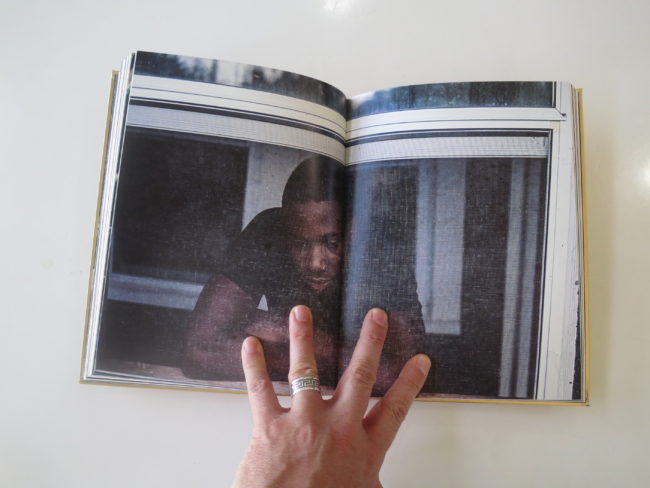

The ravages of poverty that ensnare so many in towns like Flint have hit hard, as the family has moved around a lot. The girls’ mother had difficult, live-in boyfriends.

No stability at all.

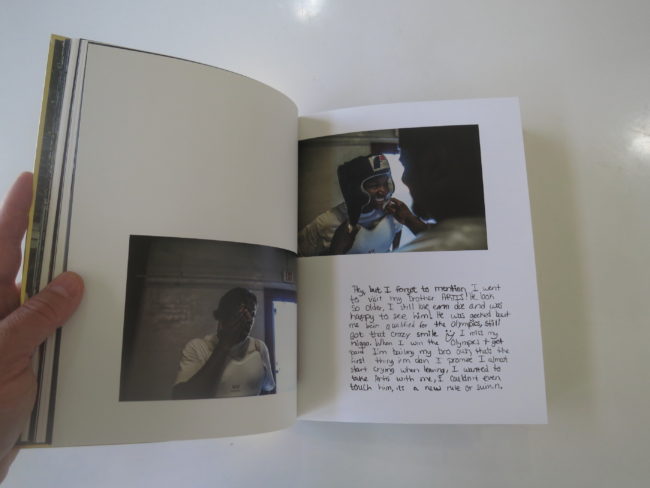

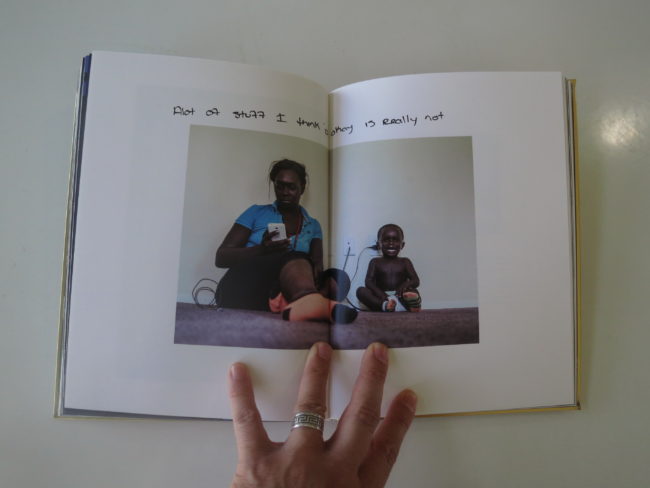

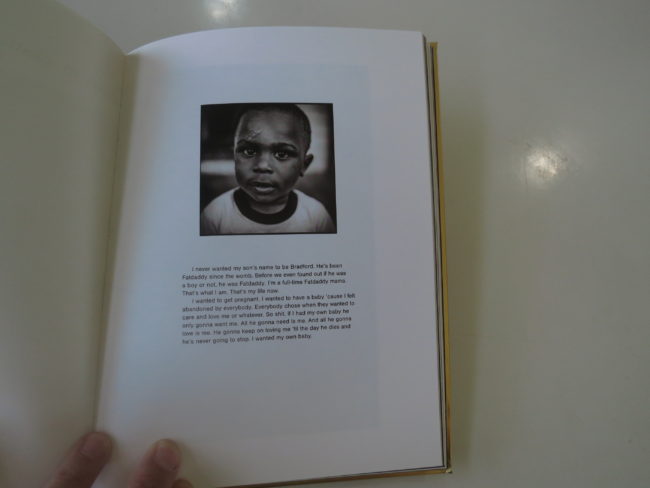

The photographs of the girls’ lives are interspersed with text bits. The hand-written nature of the words suggests intimacy. Honesty. Direct to us.

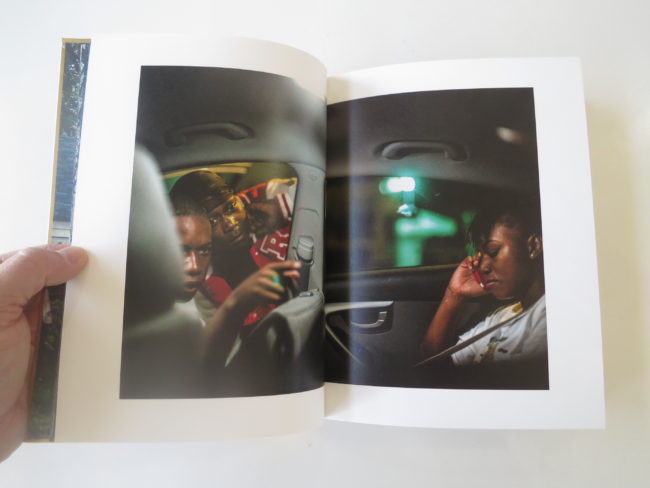

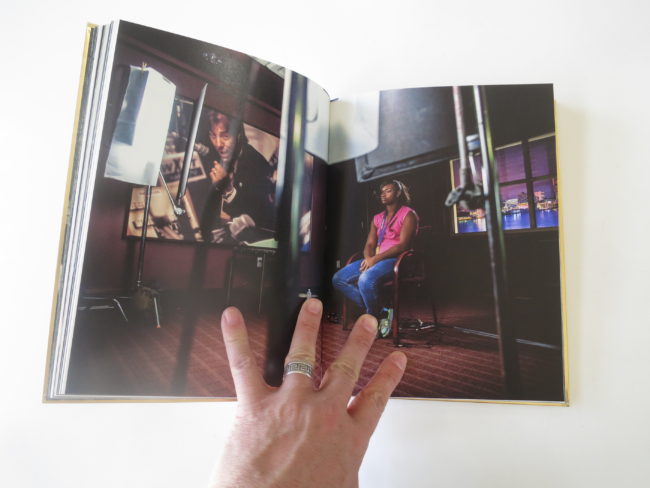

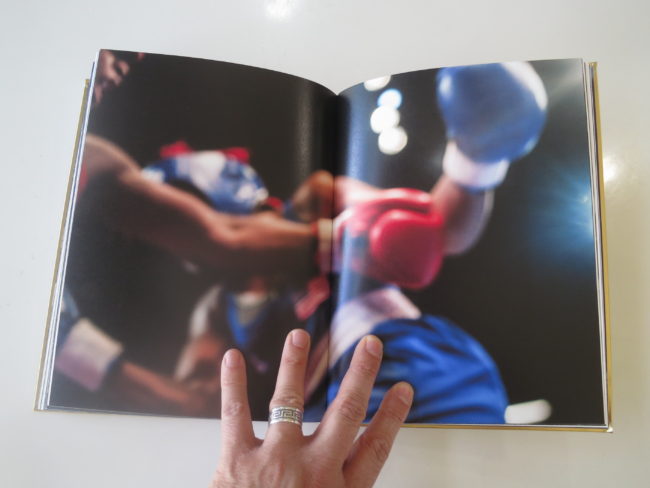

It’s an engaging book, and the pictures are really well-made. I normally don’t quibble about such things, but having every picture spread over both pages, split in the middle, was a bit distracting. (I’m guessing they thought it was worth it, to make the pictures pop a little larger.)

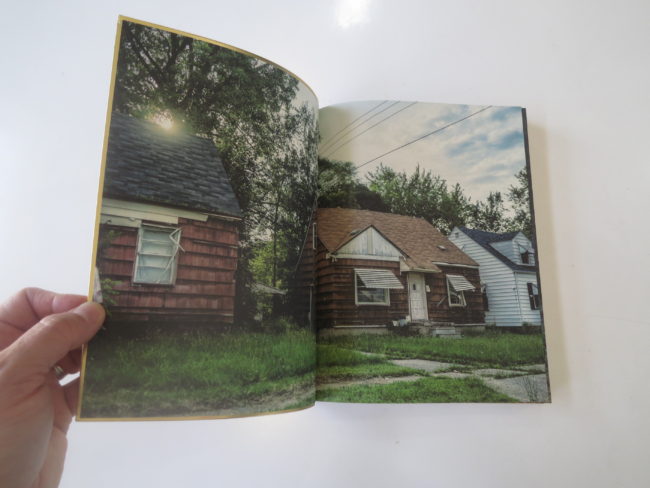

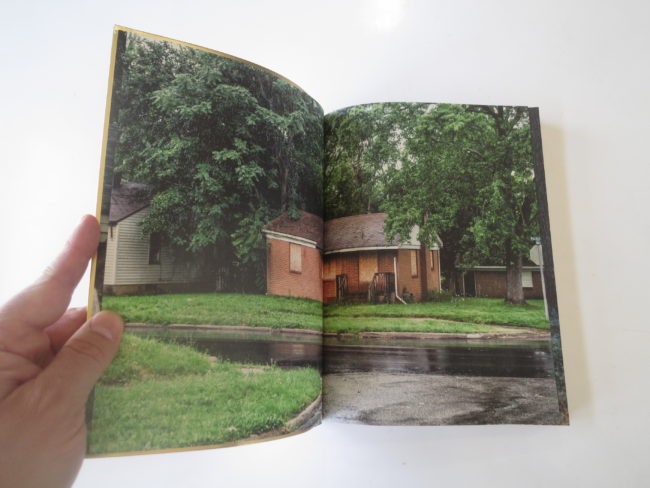

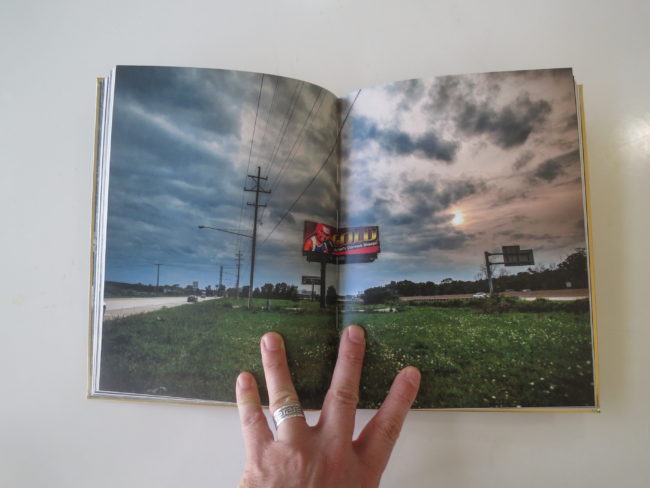

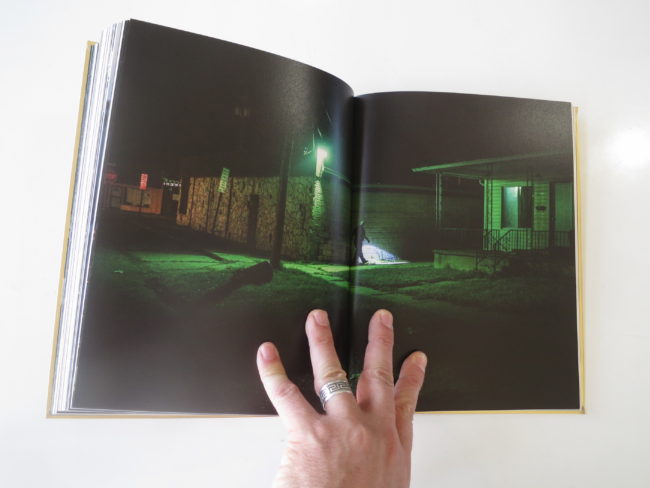

Oddly, one of the most memorable parts of the book was the silent opening. Quiet, sad, empty, green neighborhoods beckon us. The pictures were visceral, and put me in the mood. (It’s funny how words sometimes get in the way.)

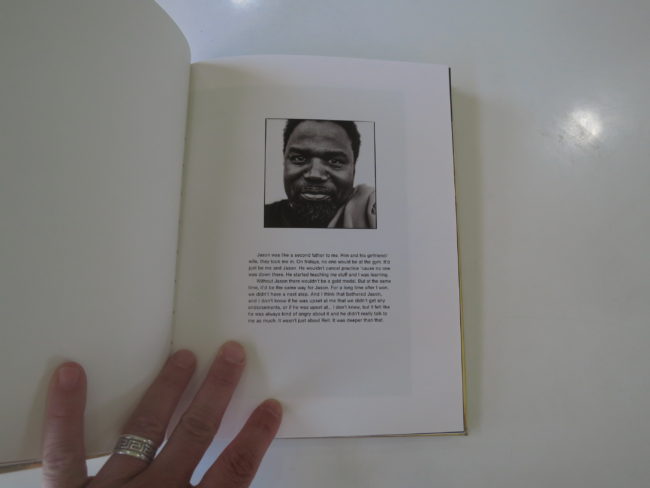

The book is well-produced, and has a nice narrative pacing. The portraits are always well-lit, and there’s a slickness to the photographs that belies a skilled technician as well.

I have to admit, though, I wonder when a story is mined in this many ways, whether some media aren’t more effective than others? Given last week’s book review, you know I’m a fan of cinema.

One advantage to that medium is how quickly we can create empathy with characters, when we have sound and motion and music. When facial expressions are not frozen, but fluid. In book form, some of the text segments tugged at my heartstrings, but most of the pictures did not have that visceral energy.

From the thank you page, it’s clear that Mr. Canepari has grown very close with these people. I don’t doubt he is thoroughly engaged in his subject’s lives, even though their culture is not his.

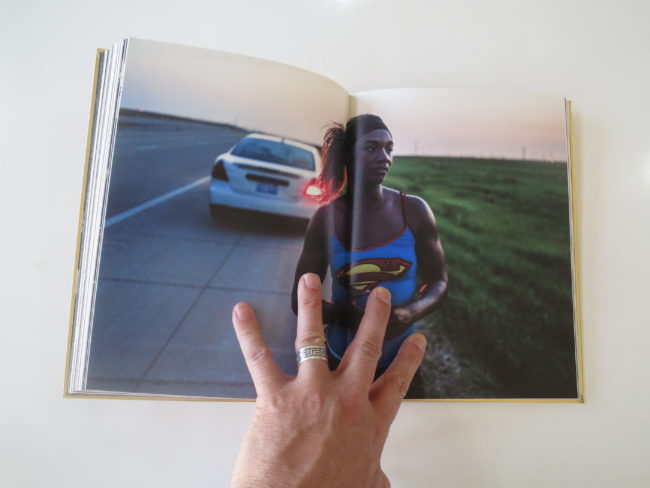

The short version is that Claressa, who won a Gold Medal in boxing at the 2012 London games, wasn’t able to escape Flint’s drama, so instead she escaped Flint entirely. She had boyfriend trouble,

coach trouble, and family trouble, so she moved to Colorado Springs to train full time at the US Boxing facility.

Her sister Briana had a kid, called fatdaddy, because she wanted a person in her life who’d love her completely. Their brother Peanut had a child too.

Their struggle represents other families, who are battling odds in dying cities, where you can’t even turn on the faucet.

In this regard, I don’t pretend to relate, which is why I turn to art to learn things I don’t understand. I would not make a photograph about what it feels like to be a poor African-American living in Flint, Michigan. Despite what I said about our commonalities as people, not everything is universal.

I applaud Mr. Canepari for having the guts to go tell a story he found fascinating. Clearly, the sisters embraced him in their lives, and want their story shared with others. I think I’ll have to see the movie, because I’m curious, but the book’s pretty good too.

Bottom Line: Slick, dynamic story about a young, female, Gold Medal boxer from Flint

To purchase “Rex” visit Contrasto’s website

If you’d like to submit a book for consideration, please email me at jonathanblaustein@gmail.com

1 Comment

Generally, I’m opposed to censorship of any kind- and I say generally because in real life, there are always exceptions for just about anything. And I agree with Mr. Berger’s assessment of the Schultz painting (if I read him correctly)- anyone and everyone should be free to artistically express themselves. But then, one should also be prepared for the criticism- better yet, one should do their HW well beforehand to engage with the community and said subject matter in a responsible manner, particularly subject matter so wrought with social tension, appropriation and animosity. Not to do so, endangers said work as an act of self aggrandizement, no matter the sincerity of intent.

Rex seems exceptionally well done: its visual pacing, overall layout- and the photographs themselves! The documentary is also recommended…

Comments are closed for this article!