How do you know you’re having a really bad day?

When you make a pregnant woman cry.

That’s always a good way to gauge when everything’s gone wrong.

If you’re not perfectly sure, having her young husband scream in your face, in public, will carry the point home.

Yes, you’re having a really bad day.

For sure.

That was a part of my yesterday, when two of my Art History students had simultaneous meltdowns. On the last day of class. Of course a year that has pushed me harder than a crowd of Walmart shoppers on Black Friday would end on such a note.

Pure. Bloody. Chaos.

It was my first time teaching this demographic before. And this class as well. (Intro to Art) So I needed to suss out the capabilities of my students, over the course of the term. Stunned, I found that half the class failed a mid-term I felt was pretty easy.

Then I heard most teachers resorted to doing open-book-open-notes tests all the time. My wife suggested I pivot to a final presentation, rather than a test, to avoid causing further stress upon them. (Some left entire pages blank, in pure freak out mode. I had to curve the thing 16 points, in the end.)

Cue yesterday, when the shit really hit the fan. Their presentations were so bad that pure plagiarism from the Internet, read aloud with many mispronunciations, became good work by comparison.

One student did a presentation on Michael Angelo. (Tony Angelo’s older brother?)

I suppose I ought to take some of the blame, as an instructor. I could have been more clear about my expectations.

But sometimes, no matter how hard you try, you can’t get through to people.

Other times, though, you can see Art make a difference in someone’s life. As a form of communication, it is something to behold. You witness it, and are reminded why this work is so important, poor pay be damned.

I had two photo students this semester who both used a photography project to conquer some deeply held fears. Both reconciled themselves; succeeding in ways our class simply couldn’t believe. One regained the ability to drive, after making pictures about a terrible car accident; the other confronted PTSD.

Art works because it allows people to take control over how they release their energy into the world. Instead of repressing rage, which eventually surfaces in violence and/or misery, we can transform it into a beautiful or ugly piece of art.

Making things is a transformative process: it takes what’s inside us, and births it into the world.

It allows for catharsis.

I saw it so many times, in the decade I worked with at-risk teenagers in Taos. It’s inspiring, the way they embrace creativity so easily at that age.

Their intelligence is there. They’re as smart as adults. They just don’t have the life experience to know what the world is about, nor the emotional maturity, and often have strong triggers from coming up hard.

I once had a student who would walk home 4 miles from work, getting in after 1am, just to wake up at 6 to get ready for high school again.

Kids who had nothing handed to them in life.

Kids like that often end up in the juvenile justice system, at some point. And what exactly does that look like?

I just put down “Corrections,” by Zora J Murff, recently published by Ain’t Bad Press, with a foreword by Pete Brook, noted expert about America’s Prison System, and author of the blog Prison Photography.

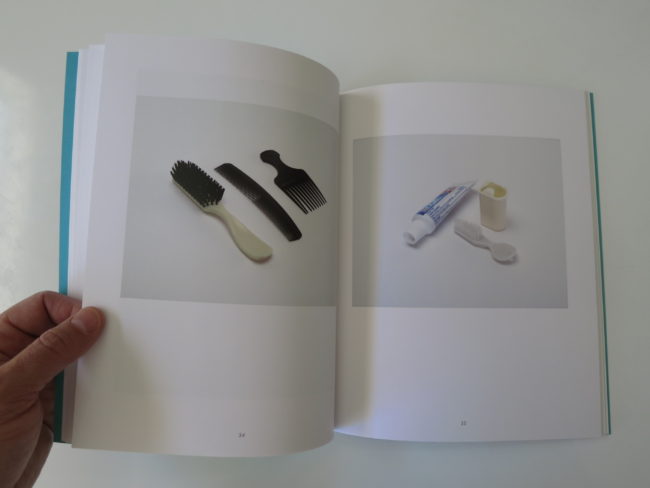

The object is genuinely beautiful, with a turquoise cover that makes me think of the Four Corners, and a graphic icon, meant to evoke the panopticon, that looks like a distorted Zia from there as well. (Navajo Nation, for the uninitiated.)

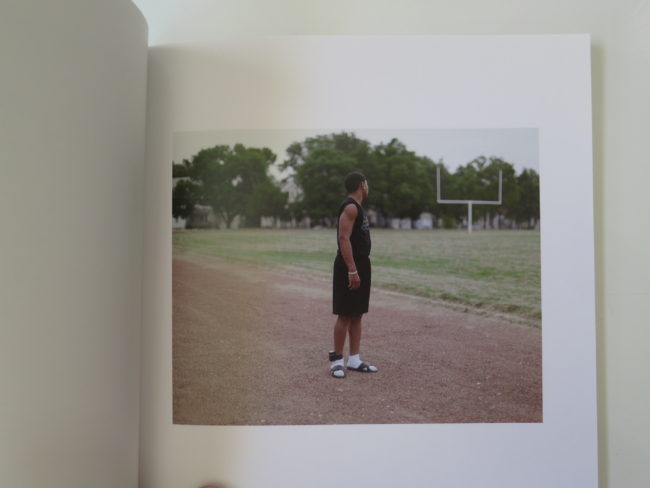

Pete’s intro suggests, but does not declare, that Mr. Murff worked inside the corrections system, in Iowa, minding the tracking devices placed on teenagers within “the system.” Kids who’d committed offenses, obviously, but not so bad they had to be in juvenile detention. (Jail.)

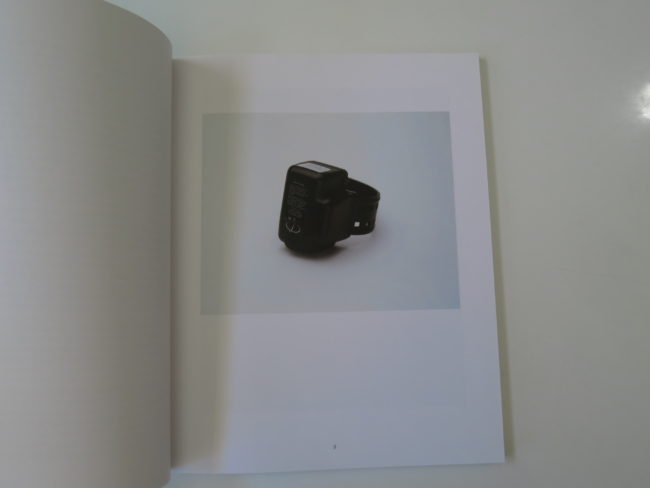

Apparently, GPS accuracy means the government really can know where ankle-tagged people are at any given time. How degrading is that? Is it not 1000 times better than being locked up?

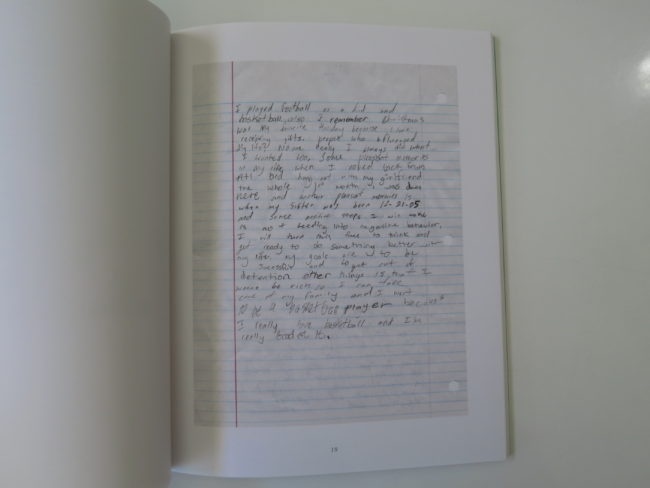

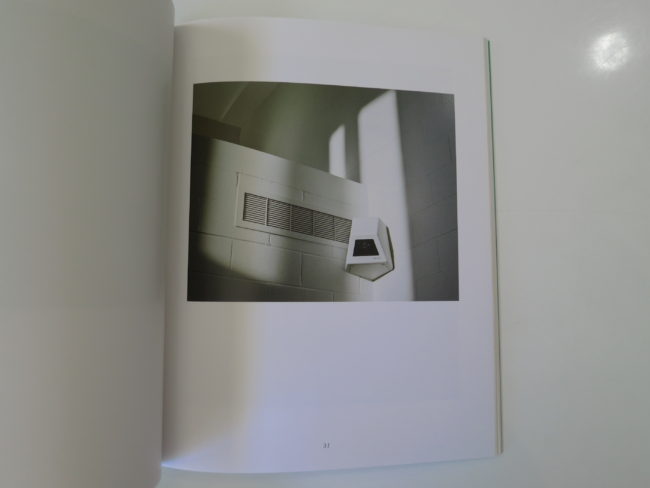

Well, we get to see and feel what it’s like, in these exceedingly well-made photographs. We’ve seen this book type before, maybe the Christian Patterson-style of mixing up all different sub-genres: historical, paper documents, still lives, portraits. (Surely, there were people who did it before CP, but you know what I’m talking about.)

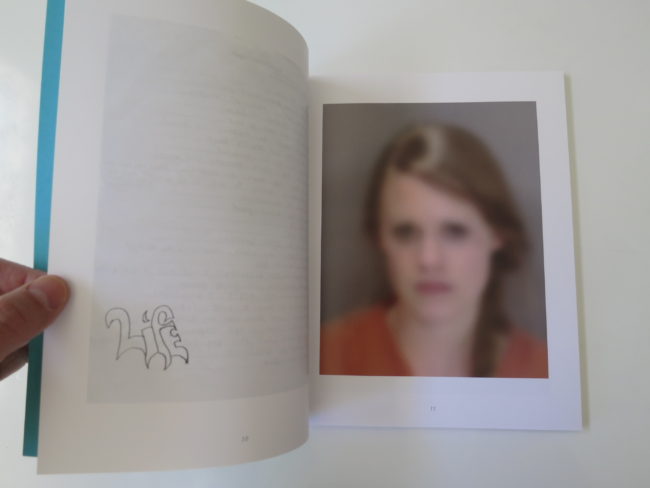

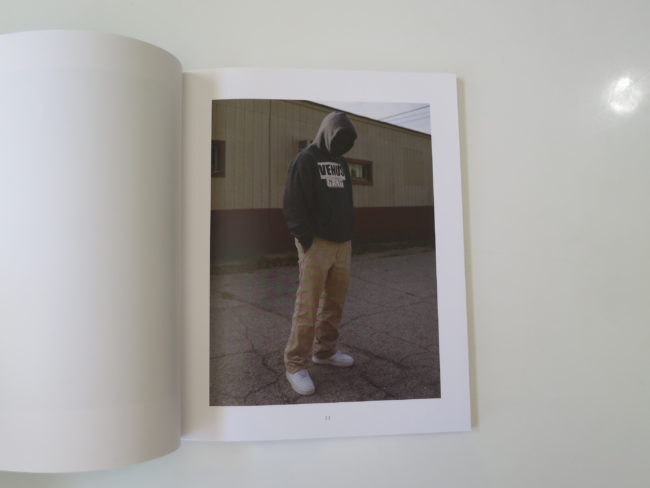

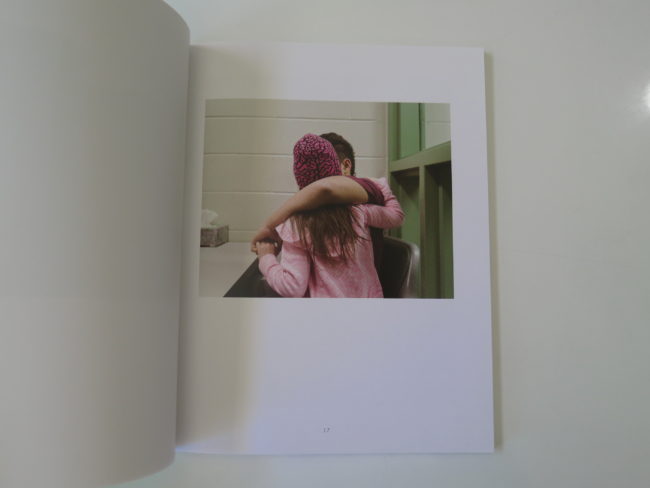

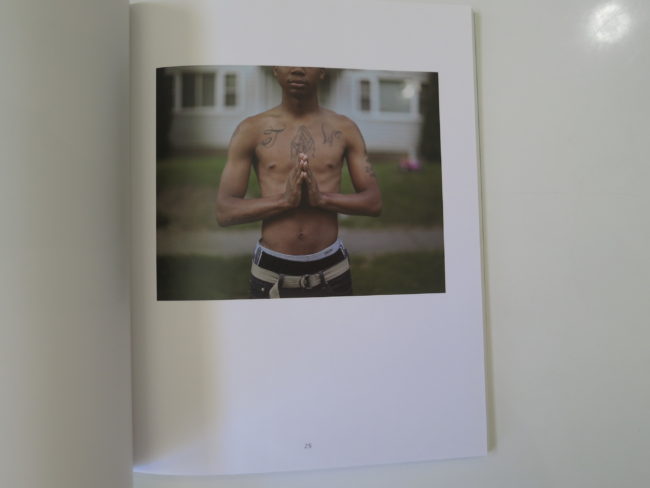

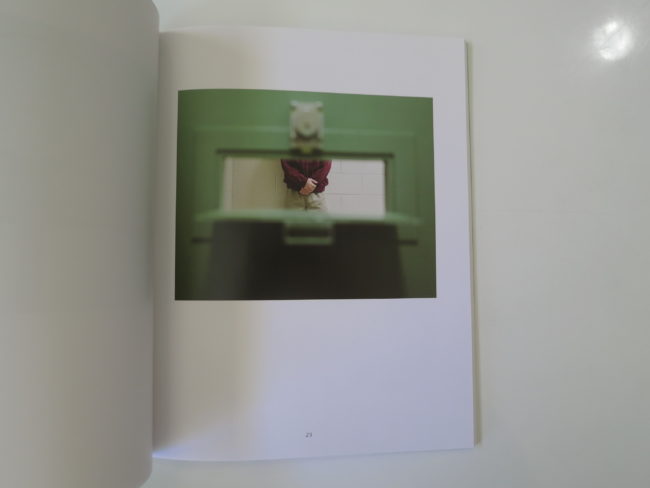

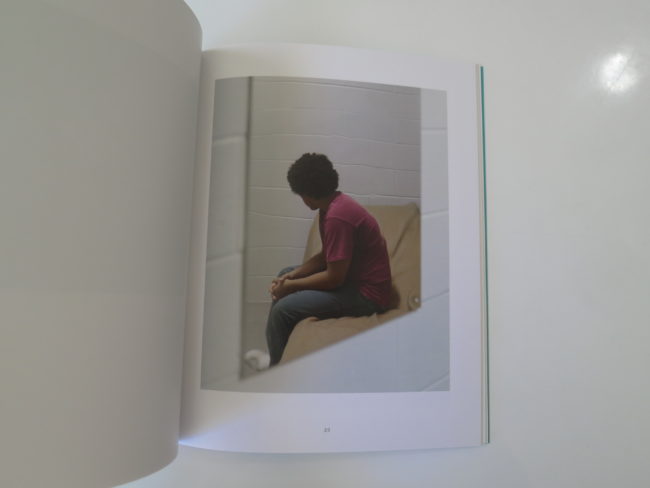

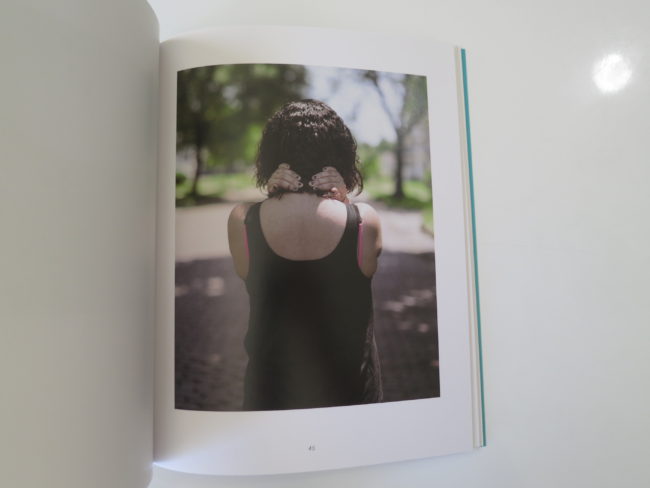

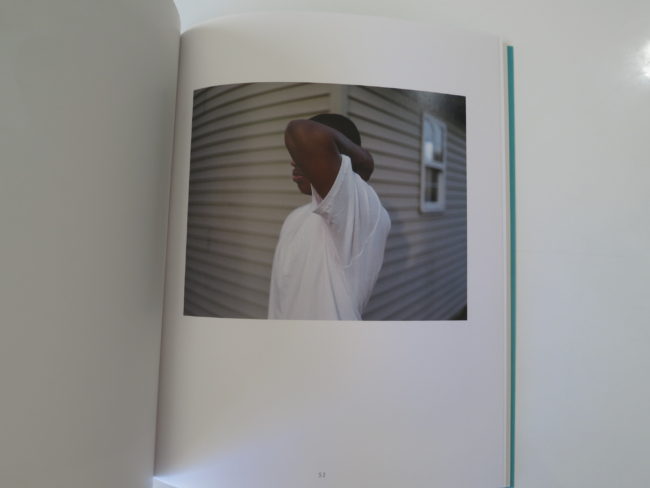

The ankle bracelet, followed by a blurred portrait, and then all the other people are shot with faces obscured. Not by big blocks or dots, but by gesture. A hood, an arm, a turned body. They don’t want us to know who they are, but they want us to know their stories.

Fair enough.

The clean graphic design on this book, the high quality of the pictures, the substantial feel, create a platform for emotions to translate.

Sadness chief among them.

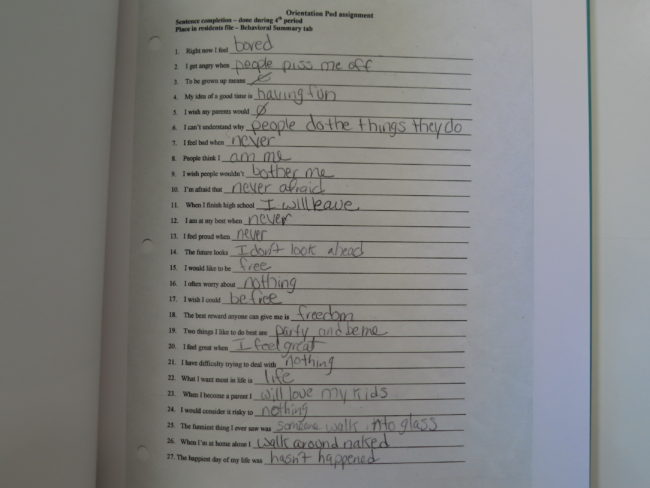

There’s a document on page 53. (See photo below.) An orientation pod assignment. Sample questions? I am at my best when: never. I feel proud when: never. The happiest day in my life was: hasn’t happened.

Heartbreaking stuff.

I really felt it. I look at so many books, as you well know, but few get under my skin.

You could say that these kids are lucky. It’s much better than being in jail. But the vibe here is that they’re not lucky at all. They’re caught in a feedback-loop incarceration system that is ruining millions of lives and costing billions of dollars.

How often do we REALLY contemplate that our governments send billions of tax dollars to private corporations to incarcerate people for profit? Or that the failed drug war is enriching corporations, while devastating countless communities on both sides of the US-Mexico border. (Who gets rich off of opioid epidemics? Cartels, pharmaceutical companies and private prisons.)

A book like this can make you think about such things.

The epilogue states that Mr. Murff in fact worked as a “Tracker” in Iowa for 3 years, 2012-15. He worked within this corrections system, and was likely in charge of many of the young people in this book. (Unless the pictures are staged.) He had to go on the trauma rides with them, and presumably it was a stressful experience. (The very-well written statement confirms as much.)

One could easily see this art project, making the pictures for the book, even the book itself, as the product of one artist’s personal catharsis.

Composting stress into beauty. Getting our attention, and turning it towards larger issues plaguing this great country of ours.

Bottom Line: Beautiful book about life inside the system